new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: international market, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: international market in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Cynthia Leitich Smith,

on 10/24/2016

Blog:

cynsations

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

giveaway,

Aboriginal,

Ambelin Kwaymullina,

author-illustrator,

international market,

Ambelin-Cyn series,

own voices,

diversity,

indigenous,

Add a tag

By

Ambelin Kwaymullinafor

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

CynsationsThe first of a four-installment dialogue with Ambelin and Cynthia. Our focus is on the creative life and process, speculative fiction, diversity, privilege, indigenous literature, and books for young readers. I am an Aboriginal author, illustrator and law academic who comes from the Palyku people of Australia.

And I am an

Own Voices advocate, by which I mean, I promote the stories told by marginalised peoples about our own experiences rather than stories told by outsiders.

I’ve written before that

I don’t believe the absence of diversity from kids lit to be a ‘diversity problem.' I believe it to be a privilege problem that is caused by structures, behaviours and attitudes that consistently privilege one set of voices over another.

Moreover, the same embedded patterns that (for example) consistently privilege White voices over those of Indigenous peoples and Peoples of Colour will also work to privilege outsider voices over insider ones, at least to some degree.

The insider voices, of those fully aware of the great complexities and contradictions of insider existence, will always be more difficult to read and less likely to conform to outsider expectations as to the lives and stories of ‘Others’.

Insider stories can therefore be read as less ‘true’ or trap an insider author in a familiar double-bind – if we write of some of the bleaker aspect of our existence we’re told we’re writing ‘issues’ books; if we don’t we’re accused of inauthenticity.

I would like to think that as an Indigenous woman, I have some insight into marginalisation not my own. I have always thought that any experience of injustice should always increase our empathy and push us towards a greater understanding of injustice in other contexts.

But that does not mean my experiences equate to that of other peoples.

In an Australian context, I have said that I do not believe non-Indigenous authors should be writing Indigenous characters from first person perspective or deep third, because I don’t think a privilege problem can be solved by writers of privilege speaking in the voices of the marginalised.

And I apply the same limitation to myself in relation to experiences and identities not my own.

Ibi Zoboi recently

wrote powerfully to the perils of the desire to ‘help’, noting that White-Man’s-Burdenism is not limited to White people. I run writing workshops for peoples who come from many different backgrounds of marginalisation, and as a storyteller, it is tempting to enact that instinct to ‘help’ into a narrative, to highlight the struggles of workshop participants in one of my own stories.

But between the thought and the action must come the process by which I determine if I am really helping at all.

So I ask myself, is the story mine to tell? The answer is no, of course; their stories are their own and their pain is not my source material.

The only way in which I would write from someone else’s perspective is in equitable partnership with someone from that group (where copyright, royalties and credit are shared).

This would not necessarily mean we each wrote half a novel. The other person may not write a word; their contribution could be in opening a window onto insider existence and correcting the mistakes an outsider inevitably makes.

I’ve had people tell me that this is the job of a sensitivity reader. But I

am cautious about the boundaries of that relationship because I think there are cases where the input of an insider advisor infuses the narrative to such a degree that they are really a co-author and should be treated as such.

I don’t think the question is who wrote what words, but whether the story could have been told at all but for the contribution of the insider.

Someone once told me that I was restricting myself as a storyteller. I don’t believe I am.

I am acknowledging boundaries, but boundaries do not necessarily limit or restrict. Boundaries can define a safe operating space, for myself and for others, and respect for individual and collective boundaries is part and parcel of acknowledging the inherent dignity of all human beings.

I have begun co-writing a speculative fiction YA novel that is told from the perspectives of two girls: one Chinese, and one Indigenous. I am writing the Indigenous girl, and Chinese-Australian author

Rebecca Lim is writing the Chinese girl.

The original idea for the story was Rebecca’s, but already it is changing as we each negotiate our own identities and experiences.

This is not a story that is restricted by boundaries; it is one that would not exist without them. In the writing of it, Rebecca and I are creating something that is greater than the sum of both of us – and in such stories, I see the future.

a Rafflecopter giveaway

|

| #WorldKidLit Month image (c) Elina Braslina |

By

Avery Fischer Udagawafor

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

CynsationsSeptember is

#WorldKidLit Month, a time to notice if world literature is reaching kids in the form of translations.

(See this

Book Riot list of 100 Great Translated Children’s Books from Around the World.)

Leading the effort are Cairo-based writer Marcia Lynx Qualey, translator Lawrence Schimel, and Alexandra Büchler of

Literature Across Frontiers.

I was fascinated that

Qualey, a journalist for The Guardian and other outlets, takes such interest in children’s literature. She answered my questions for Cynsations by email.

As a journalist, why have you made #WorldKidLit Month a special project? Many of the books I see promoted as “Middle Eastern literature” for children—indeed, almost all of them—are books written by Westerners and set in the region. Just so, we have floods of books by soldiers, aid workers, and journalists who spent some time in Iraq, for instance, and almost none by Iraqis.

Writing about other places is valuable, yes, but it’s another thing entirely to listen to the stories—the cadences, the art, the beauty—coming from another language.

I find it limiting and echoey to read the narrow band of “our own” Anglophone stories. We can offer our children much much more: more joy, and more ways of seeing.

What would you like the children’s literature community to gain from this annual event? Just as with

#WiTMonth (Women in Translation), I think it’s key to start with recognition—to recognize that we don’t translate much from around the world. We translate a bit from Western European languages, where publishers have connections, and that’s great. But the literature currently translated from the great Indian languages, from Chinese, from Turkish, from Farsi, from Eastern European languages, would fill a few small shelves. These literatures could give us so much!

I’m grateful for the bit translated from Japanese literature, which has been feeding our children’s imaginations in new ways. (And our grown-up imaginations, too.)

What was your own experience of literature as a child? Was your whole world represented in stories you read? The world outside was a mysterious and scary place, difficult and sometimes painful to understand. But the worlds as presented in my books were so tangible, they really belonged to me, they could be read and re-read.

As for translations, I particularly loved folktales from around the world, and cherished not just

Italo Calvino’s collection (which I read until it fell to bits), but Norwegian and Japanese and Arab and other folktales. The folktale is a wonderful global form where there has been much sharing from language to language, culture to culture.

Have you translated any literature for children? Not in any serious or systematic way; just helping translate picture books for a friend. I would love to, but interest in Arabic kidlit has been vanishingly small.

What currently available Arabic>English kidlit translations would you recommend? There are precious few, while children’s books translated into Arabic are many. (There are books from French and Japanese, for instance, that I know and love only in Arabic.)

You can get a translation of pioneer illustrator

Mohieddine Ellabad’s The Illustrator’s Notebook, and

The Servant by Fatima Sharafeddine (Faten, in the original, translated by Fatima herself), and

Code Name: Butterfly by Ahlam Bsharat, translated by Nancy Roberts. I would love you to read Walid Taher’s award-winning Al-Noqta al-Sooda’, but alas there is no translation!

Cynsational NotesMarcia Lynx Qualey blogs at Arabic Literature in English.

Avery Fischer Udagawa contributes to the

SCBWI Japan Translation Group blog and is the

SCBWI International Translator Coordinator.

By

Misa Dikengil Lindberg,

Alexander O. Smith and

Avery Fischer Udagawafor

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

CynsationsThis month, the

Asian Festival of Children’s Content in Singapore will feature Cynsations’ own Cynthia Leitich Smith speaking on “The Irresistible Fantastical Supernatural: Writing a World that Beckons.”

Also featured at AFCC 2016 will be Cathy Hirano, a leading translator of Japanese children’s literature into English.

Hirano’s translation of the middle grade realistic novel The Friends (by Kazumi Yumoto) won the Boston Globe-Horn Book Award for Fiction and a Mildred L. Batchelder Award. Her translations of the YA fantasy novels

Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit and

Moribito II: Guardian of the Darkness by Nahoko Uehashi won the Batchelder Award and a Batchelder Honor, respectively, and paved the way for

Uehashi to win the Hans Christian Andersen Award for Writing. This honor is often dubbed the Nobel Prize for children’s literature.

In addition, Hirano translated a YA fantasy novel by Noriko Ogiwara that went out of print, but drew such a fan following that it was republished with a sequel. The results are

Dragon Sword and Wind Child and

Mirror Sword and Shadow Prince.

Members of the

SCBWI Japan Translation Group have admired Hirano for years. Three members of the group—Misa Dikengil Lindberg, Alexander O. Smith and Avery Fischer Udagawa—interviewed her for Japan-focused publications and here combine their efforts in a “pre-

AFCC 2016 omni interview.”

To learn more about the topics discussed in this piece, please follow the links below it to the three source interviews. And don’t forget to enter the Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit giveaway!

Avery Fischer Udagawa: Cathy Hirano, you work as a translator in fields such as anthropology, sociology, architecture and medicine, and you live in Takamatsu, Kagawa Prefecture, Japan. Where did you grow up, and how did you come to study Japan and Japanese? |

| Cathy Hirano |

Cathy Hirano: I grew up in Vancouver, Victoria and Winnipeg and came to Japan in 1978 when I was 20. I was not directly interested in Japan at the time but was invited by a Japanese-Canadian friend. My image of Japan was of a highly populated, highly polluted country that manufactured cars and cameras—not a very attractive picture. I had very little idea of Japan’s history or culture and saw traveling here as a stepping-stone to other countries in Asia, and then to the rest of the world.

But my interest in Japan and the Japanese language began as soon as I arrived in Japan. I got lost in Tokyo on my second day here and realized that if I did not acquire reading, writing and speaking skills, I would be lost forever in more ways than one.

I studied for a year in Kyoto at a private language school called Nihongo Kenkyu Center. It was very small with creative teachers who were always experimenting with new methods. I fell in love with kanji [ideograms] at that time. The concept that a “letter” could be a picture with meaning was fascinating. To help memorize them, I used to make up my own stories about how each part of a kanji combined to make the meaning of the whole. In 1979, I went on to study anthropology at International Christian University in Tokyo, which had a fantastic Japanese language program.

How did you discover and cultivate your skills as a translator?I think it was my Japanese teachers in Kyoto and at ICU who first pointed out to me that I had some ability in this area. Reading has always been a great source of pleasure, inspiration and comfort, and when we had to do translation exercises in class, I wasn’t content with just a literal translation. I had to play with it until it sounded as natural and literary as the Japanese.

Cultivating my translation skills was very much a hit-and-miss, learning-on-the-job experience. I was hired as a translator by a Japanese engineering consulting company after I graduated.

I didn’t know any other translators when I started out, and as far as I knew there were no courses in translation. So I read as much as I could in English about whatever subject I was translating to get a feel for the right language, consulted the Japanese engineers I worked with frequently to make sure I understood, used the dictionaries and references in their library and got native speakers (including my father, who is an engineer) to read what I had written and give me feedback.

This is still the approach I use today for any type of translation. The only difference is that with the Internet, I no longer need to accumulate reference books and dictionaries. Thanks to email, I also have an extended network of friends and relatives, both Japanese- and English-speaking, who I can consult for different subjects.

You have translated a number of picture books—most recently Hannah’s Night by printmaker-illustrator Komako Sakai, for Gecko Press—as well as novels. What attracted you to children’s literature?I fell into children’s literature entirely by accident. A friend and fellow graduate of ICU who worked in publishing asked me to review English-language children’s books for possible translation into Japanese, a dream job for someone who loves reading. She would give me a stack of books, and when I had finished reading them I would meet her in a coffee shop and tell her what I thought.

She then began asking me to translate Japanese picture books for promotional purposes. My publications of picture books started out as byproducts of the promotional translation: English-language publishers liked the translations and asked for permission to use them.

Meanwhile, when my friend’s company published an award-winning novel by Noriko Ogiwara, I agreed to read it and write a summary. This was followed by a request for a sample and finally to translation and publication of Dragon Sword and Wind Child. This then led to translating three novels by Kazumi Yumoto for Farrar, Straus and Giroux—including The Friends.

Alexander O. Smith: An essay you wrote for The Horn Book about The Friends has become a classic description of Japanese-to-English literary translation. To follow on that discussion, how do you position yourself as translator with regards to the work, the author, and your audience?I think that my approach as a translator differs significantly for bread-and-butter translation and for literature. With the former, I am more objective. I keep a clear picture in my mind of the target reader and I focus on conveying the intent and meaning of the Japanese rather than on the style, sometimes extensively editing and rewriting the original.

With literary translation, however, I find the translation process more personal and subjective. The author has written the book for me and I’m translating it so that others can enjoy the same experience. In the initial stages in particular, I don’t worry about the readership and instead focus far more on the author, on his or her style, choice of words, rhythm—on the voice. I’m quite faithful to the original.

It is only when I go back and reread it, that I regain some objectivity and become rather ruthless. But I am still trying to convey an experience rather than just content or meaning.

Misa Dikengil Lindberg: Your first novel translation, of Dragon Sword and Wind Child, got republished with a sequel after it fell out of print. How did that come about?I loved Noriko Ogiwara’s Magatama series and was therefore very disappointed when Dragon Sword and Wind Child went out of print.

Then my daughter grew up and fell in love with Ogiwara’s books as a teenager. Searching the Internet, she found that the English translation had received nothing but five-star reviews on Amazon. She also found used copies selling for up to five hundred dollars and one young reader who had made a website dedicated to the book. This person had even typed the entire out-of-print English translation to put on the site! I was stunned. People had actually liked the book as much as I had!

I contacted the Japanese editor to see if there was a possibility of re-doing it, although I knew most American publishers would be reluctant to publish a book that hadn’t done well before. The editor, who also loves the book, began putting out feelers.

Although we did not know this, around the same time, VIZ Media had decided to branch out into publishing translated Japanese literature and was looking for good Japanese books. One of their editors had read Dragon Sword and Wind Child when she was young and loved it.

When the editing team tried to get a copy of the English translation for review, they found that the majority of library copies had been stolen, which actually made them more interested in the book, indicating as it did how popular the book was. They eventually got a copy and decided to republish it. The original English-language publisher agreed to give them the right to publish it but not the rights to my translation. When the VIZ editor contacted the Japanese publisher, she put them in touch with me and they asked if I would “re-translate” it. Of course, I was thrilled!

Alexander O. Smith: What was it like revisiting the first volume fourteen years after your first translation? It was fun, embarrassing, unnerving, confirming. I started by reading it aloud to my kids and their cousins, who by then were in their mid and late teens. They loved it, thank goodness! But they also had some good laughs about some of my word choices while I found myself cringing in places where the language I’d used was stuffy and stilted.

I then went through the translation line by line against the Japanese and caught things I had missed or misunderstood—not as many as I had feared, but still. After rewriting all the trouble spots, I did a final pass through the whole book.

Although it was embarrassing to see the mistakes I had made, it was also confirming to see that I have evolved somewhat as a translator in those 14 years and that I still love to escape into Ogiwara’s world!

How was it to do the sequel?In a nutshell, the knowledge that people were waiting to read Mirror Sword and Shadow Prince is what kept me going. Readers have power!

Misa Dikengil Lindberg: Nahoko Uehashi’s ten-volume Moribito series, about the adventures of a young female bodyguard, is the winner of numerous literary awards and has become hugely popular in Japan, even spawning anime, manga, and TV series. How did you first encounter Uehashi’s work? |

| Japanese and English covers |

My first exposure to Ms. Uehashi’s work was in 2004, when I was asked to do a summary and sample of

Beyond the Fox’s Flute. I was attracted by Uehashi’s writing style and by the fictional world she created. Around the same time, a Japanese friend told me about her Moribito series, and I found it intriguing that a children’s fantasy series was so popular even with people my age (fifty).

Before I had a chance to read the series, however, the Japanese publisher contacted me to do a summary and sample translation of the first book for overseas promotion.

This led to publication of Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit and later Moribito II: Guardian of the Darkness by Arthur A. Levine Books.

How closely did you work with your editor at Arthur A. Levine Books, Cheryl Klein? What were some of the problems you worked to overcome?Cheryl Klein is the most thorough editor I have ever worked with. She edited the translation as if it were a new manuscript submitted by an English-language author, which made some of her suggestions extremely radical. As Ms. Uehashi is also one of the most thorough and involved authors I have ever worked with on a translation, the result was definitely a team effort.

Probably the biggest problem was fitting the history of New Yogo (the fictional empire in which the story takes place) into the book in a more natural way.

When I first read Moribito in Japanese, the history stuck out awkwardly in the third chapter, slowing everything down. Until that point, the action is fast-paced and the story gripping. Then suddenly the text switches to an unnamed narrator, jumps back in time, and then jumps back to the present again.

It’s quite abrupt and would have sounded unnatural in English. So when I did the initial sample translation, I took it out (with the author’s and publisher’s permission) and tacked it on as a prologue with a note explaining that this would need to be solved during the editing process.

After playing with several ideas, the three of us finally agreed that the history basically belonged in its original location but that English readers needed more of a transition to ease them into it and keep them from getting impatient during that section.

Ms. Uehashi rewrote certain parts of the history, replacing the unnamed narrator with the more personal voice of Shuga, one of the Star Readers. So the English version is actually different from the Japanese but still written by the author.

Alexander O. Smith: The Moribito series and the Magatama series are interesting to me in that they both fit snugly within a very western fantasy genre and yet their stories and worlds are influenced by Asian history and myth. How did you navigate the process of bringing these worlds into English without losing the flavor of the original? Were you inspired, stylistically or otherwise, by any other books in English?A hard question! For me, it’s a very intuitive process and I’m never sure if I really have succeeded in keeping the flavor of the original. One thing I try to do is read the translation out loud once I get it to a more polished state. That helps me see whether it “feels” the same.

What I’m looking for at a gut level is whether the English grabs me in the same way as the Japanese. To me, Uehashi’s voice is fast-paced, powerful, compassionate, clear and deceptively simple. Ogiwara’s voice, though just as powerful, is completely different. Her rich, lyrical images and sweeping descriptions vividly convey the emotional atmosphere. She has a knack for capturing a focal point or detail that draws in the reader and for mirroring the inner worlds of her characters’ minds and hearts in the outer world. However, this style, which is very Japanese, is less compatible with the English language than Uehashi’s.

To give one example, Uehashi’s battle scenes are graphically detailed. You know exactly when and how each bone is broken, whose bone it is and what it feels like (ouch!!). This brings home the reality of life for the bodyguard Balsa.

As for what books inspired me during the translation process, I actually strive not to be influenced stylistically by other authors so that I can remain true to the original. At the same time, however, I do read books in the same genre because exposure to good English helps me avoid an excessively literal translation.

While translating the Moribito books I found myself rereading

Ursula LeGuin’s

Earthsea series. I think what appealed was their common themes such as the search for meaning, the painful journey of self discovery and acceptance, and the fact that their voices both evoke the oral tradition of story-telling.

When translating Ogiwara, on the other hand, I was drawn to

Tolkien’s

The Lord of the Rings. Again, it wasn’t the style but the story’s epic nature and the use of humor to lighten a serious tale that resonated.

Avery Fischer Udagawa: Are you at work on any children’s or young adult projects now?Yes, I am getting a start on The Beast Player (Kemono no soja), a fantasy novel by Andersen laureate Nahoko Uehashi.

Cynsational Notes: Interviewers & Source InterviewsMisa Dikengil Lindberg is a freelance writer, editor and translator. She translated the new adult novel Emily by Novala Takemoto and the story “The Dragon and the Poet” by Kenji Miyazawa (1896-1933), one of Japan’s most beloved writers, for the anthology Tomo: Friendship Through Fiction—An Anthology of Japan Teen Stories. Her full interview with Hirano,

Young Adult Fantasy in Translation: An Interview with Cathy Hirano, focuses on Dragon Sword and Wind Child and Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit.

Alexander O. Smith is the translator of thirty novels from the Japanese, including Brave Story and The Book of Heroes by Miyuki Miyabe, The Devotion of Suspect X by Keigo Higashino, and the Guin Saga series by Kaoru Kurimoto. He is also known for localization and production of video games, and is co-founder of publisher Bento Books. His full interview with Hirano,

Catching Up With Cathy Hirano, focuses on Mirror Sword and Shadow Prince.

Avery Fischer Udagawa translated the middle grade historical novel J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965 by Shogo Oketani. She serves as SCBWI Japan Translator Coordinator and SCBWI International Translator Coordinator. Her full interview with Hirano,

Children’s Book Translation: An Interview with Cathy Hirano (PDF, pp. 7-9), focuses on ways to get started in translation.

Cynsational GiveawayEnter to win a hardback edition (now a collector’s item) of

Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit by Nahoko Uehashi, translated by Cathy Hirano.

The design of this volume is described here by editor Cheryl Klein of Arthur A. Levine Books:

Behind the Book: Moribito Guardian of the Spirit.

See also:

Moribito: Editing YA and Children’s Literature in English Translation: An Interview with Cheryl Klein by Sako Ikegami (PDF, pp. 4-7.

a Rafflecopter giveaway

By

Patti Bufffor

SCBWI Bologna 2016and

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

CynsationsChristopher Cheng is the award-winning author of more than 40 children’s books in print and digital formats. The picture book New Year Surprise! is his latest publication. His other titles include the picture books One Child, Sounds Spooky and Water, the historical fiction titles New Gold Mountain and the Melting Pot as well as the nonfiction titles 30 Amazing Australian Animals and Australia’s Greatest Inventions and Innovations. His narrative nonfiction picture book Python, was shortlisted in the 2013 Children’s Book Council of the Year awards, and was listed as of “Outstanding Merit” in the 2014 edition of Best Books of the Year for Children and Young Adults, selected by the Bank Street College of Education Children’s Book Committee. In addition to his books, Christopher writes articles for online ezines and blogs, and he wrote the libretto for a children’s musical.

He is co-chair of the International Advisory Board for the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI), an International Advisory Board Member for the Asian Festival of Children’s Content (AFCC) and a recipient of the Lady Cutler Award for Children’s Literature. He is also the director of the digital publishing company Sparklight. He presents in schools, conferences and festivals around the world and he established the international peer voted SCBWI Crystal Kite Awards. He dwells with his wife in an inner-city Sydney terrace and is often heard to say that he has the best job in the world! Welcome to the blog, Chris! With much more focus on diversity in children's books than has been in the past, how important of a role do you think book fairs like Bologna play in introducing young readers to children from other countries and cultures? They are critical - we move in a global sphere but we don’t all dress the same or say the same things or behave the same way thus it is important for today’s children, no matter where they are in the world, to be exposed to the authentic literature from other countries and cultures who tell ‘their’ stories with an authentic voice.

Any tips for new Bologna visitors? • It’s

big so enjoy the experience.

• Plan out what you want to see, make notes ahead of time and follow your nose.

• Make notes of what you see, how the books are displayed, how the different publishers publish their content, look at the types of books that the publishers and other organizations have on display - can you find a continual link between their titles?

•

Don't bug/hassle the publishers / agents / marketing folk etc. unless you have been invited.

•

Don't rush home (this is especially for those of the authorial persuasion) and write the book that you have decided is the ‘happening thing’ at Bologna. It will have already been done and dusted by the time you get down to it.

• There is a lot of ‘paper’ at Bologna - you can’t carry it all … but much of it will be digital!

•

Visit our SCBWI booth - we are your home away from home!

• And don’t forget to sample, no

feast, on some of the amazing food that is available in Bologna.

Bellissimo! You've had books published in markets all around the world. What do you think makes a book successful in all different types of markets? Having a global theme, like peace/war/growing up, death, childhood, animals etc.

That said I know you can’t create a book that will fit all markets throughout the world. You have to create

your own story!

I’ve read you do weeks and months of research for your historical fiction and that by the time you’re ready to write, the story has already been formulated in your head. Which I can imagine lends itself to easy drafting. But once the editing starts, have you had to ‘change facts’ for the story’s sake and if so, how hard has that been? Easy drafting for sure … not so easy for editing though! There has

always been too much in the story. I don’t think I have had to change the essential facts at all to ‘fit the story’ as my historical fiction has always been based on the facts themselves.

The facts themselves are often what make the riveting story!

You write for a wide range of ages and over a wide range of subjects and genres. What advice can you give authors who’d like to branch out and diversify their writing. Know your audience. Know the genre. Know what you are writing. If it is factual - know the facts and that goes for authors and illustrators.

Write

your story, and if it doesn’t work, then try it in a genre you are comfortable with.

And finally, what are you working on now? Any surprises you can share with us? My newest title, birthed Feb. 5 is

New Years Surprise! It was written to tie in with an

exhibition of paper art and objects, that is being held at our National Library in Canberra (our national capital) on the Celestial Empire.

At this exhibition, visitors experience 300 years of Chinese culture and tradition from two of the world’s great libraries - the National Library in China and our National Library.

From life at court to life in the villages and fields, glimpse the world of China’s last imperial dynasty and its wealth of cultural tradition.

The exhibition (and thus, by association, my book) is being launched by the Prime Minister of Australia. Woo hoo--will have the glad rags on for that! There will be lots of twittering and facebooking going on!

That’s wonderful, congratulations! Not every author can say their book was launched into the public by the Prime Minister. Thank you so much for joining us, Chris. Have a great time in Bologna! Cynsational NotesThe tenth out of eleven children in a family that took in hundreds of foster kids,

Patti Buff found solitude in reading at a young age and hasn’t stopped. She later turned to writing because none of her other siblings had and she needed to stand out in the crowd somehow.

Originally from Minnesota, Patti now lives in Germany with her husband and two teenagers where she’s also the regional advisor of

SCBWI Germany & Austria.

She is currently putting the finishing touches on her YA novel, Requiem, featured in the

SCBWI Undiscovered Voices 2016 anthology.

The Bologna 2016 Interview series is coordinated by

Angela Cerrito, SCBWI’s Assistant International Advisor and a

Cynsational Reporter in Europe and beyond.

By:

Cynthia Leitich Smith,

on 2/9/2016

Blog:

cynsations

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Erzsi Deak,

Angela Cerrito,

Doug Cushman,

author-illustrator,

international market,

SCBWI Bologna 2016,

Elisabeth Norton,

SCBWI,

illustration,

Add a tag

By

Elisabeth Nortonfor

SCBWI Bologna 2016and

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

CynsationsSince 1978, Doug Cushman has illustrated over 130 children's books, 30 or so of which he wrote as well. Among his many honors, he has gained a place on the New York Times Children’s Best Sellers list and on the 2003 Children’s Literature Choice list.The first book of his popular beginning reader series featuring Aunt Eater (HarperCollins, 1987) was a Reading Rainbow Book. He has received a National Cartoonist’s Society Reuben Award for Book Illustration, the 2004 Christopher Award for his book illustrations, a 2007 and 2010 Maryland Blue Crab Award and the 2009 California Young Readers Medal.He illustrated the best-selling “Can’t Do” series, including What Dads Can’t Do (2000) and What Moms Can’t Do (2001) for Simon and Schuster.

His recent titles include Pumpkin Time! by Erzsi Deak (Sourcebooks, 2014), Halloween Good Night (Square Fish, 2015) and Christmas Eve Good Night (Henry Holt, 2011), which received a starred review from Kirkus. His first book of original poems, Pigmares (Charlesbridge, 2012), was published in 2012. He has displayed his original art in France, Romania and the USA, including the prestigious Original Art, the annual children’s book art show at the Society of Illustrators in New York City. He is fan of mystery novels and plays slide guitar horribly. He enjoys cooking, traveling, eating and absorbing French culture and good wine—even designing wine labels for a Burgundy wine maker—in his new home in St. Malo on the Brittany coast in France.Welcome Doug! Thank you for taking the time to answer a few questions about illustration and the SCBWI Bologna Illustration Gallery (BIG) at the Bologna Children's Book Fair.

You have had a long career in the children's publishing industry, illustrating both your own stories, as well as the stories of other writers. Do you have a favorite medium for illustrating children's books? I love watercolor with pen and ink. There is so much expression one can have using ink line with the occasional “happy accidents” in watercolor. Pretty much all my books have been rendered in those two mediums.

It was more controlled in the beginning, but I’m trying to loosen up now. For a couple books I did everything: writing, watercolor illustration and hand-lettering the display type and entire text including the copyright. I even simulated aged, yellowing, lined notepad paper with watercolor, hand drawing each blue line on every page of the book.

My philosophy is: do whatever it takes to make the book work.

Has that changed over the years? Moving to Paris loosened me up a bit. A few years ago, I rendered three books in acrylic, something I’d wanted to do. I love the bright colors and thick brushstrokes. I even added some collaged elements as well.

But, for me, the medium I use depends on the story. The technique I use to illustrate a book must complement the heart and soul of the story. An illustrator should never force his style on a text.

I’ve discovered digital painting recently. There’s a lot one can do with it. I’m having a grand time playing with my Wacom tablet, but I believe my training as a traditional artist has held me in good stead. Knowing the craft of drawing and painting has always helped me out with a multitude of problems! Yet, the story always dictates how I approach the way I draw my pictures.

So it varies from project to project. What influences your choice of style and medium for a given project?  |

| Rackham |

|

| Shepard |

The story is always the first thing that defines my approach to a project, even when I’m the author. An illustrator must read what’s between the lines as well as what’s on the page. The author is telling a certain story, the illustrations must work in harmony with the text.

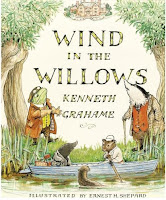

A good example is

The Wind In the Willows by

Kenneth Grahame (1908). The master draftsman

Arthur Rackham illustrated one (1940) edition.

He's a brilliant illustrator, one of my favorites. But his style was so wrong for the atmospheric and slightly goofy story (Toad driving a car!). He was perfect for Grimm but not for the animal denizens living along side an easy, flowing river.

E.H. Shepard’s illustrations are spot on.

What qualities do you think are important for an artist to have in order to be successful as children's book illustrator? Patience! Flexibility and a thick skin are paramount as well. This is a tough business. So many books are being published every year. But there’s always room for someone with a different voice, a unique way to look at the world.

Be aware of the trends but never be a slave to them. Follow what interests you. It may take longer but in the long run your work will be more sincere and that will catch the attention of editors and art directors. Honesty always shines through.

As writers, we talk a lot about voice, both the voice of the character, as well as our own authorial voice. Do illustrators have a voice as well? What about individual projects, or even characters? Absolutely, illustrators have a voice. Like writers, it’s the way we see life.

In my case, I see the silliness, the zaniness in the world and through my characters, both human and animal. I’ve been told that one of the qualities people like about my work is the expression on my characters.

That’s part of my voice, my way of interpreting a text and the world in general, that internal struggle, waiting to get out. It’s like being an actor; artists must get inside the skin of the characters they’re illustrating, feeling what they feel. But, as I said earlier, the voice of the illustrator shouldn’t interfere with the voice of the author. They need to play off of each other, work in tandem together.

As a judge for the BIG, what makes an illustration stand out to you? The BIG is a show of illustration, not just an exhibition of pretty pictures. I’m looking for art that is not only drawn and painted well, wonderfully composed and executed, but also tells a story.

I confess that much of what I see in the grand Bologna Book Fair judged art shows are marvelous paintings but they don’t tell any stories. We’re talking about book illustration here, art that serves a purpose. In many ways it’s harder and a much higher calling than easel painting.

I want to see something that dives deep into a story and tells me something in a way I haven’t seen or thought of before.

Why do you think participation in illustration showcases such as BIG is important for illustrators? Exposure is one factor. Getting noticed. Working for a specific purpose is important as well. I’ve submitted illustrations to many judged shows with very specific criteria; size restrictions, medium, subject matter, etc. I haven’t always been accepted, but in the process of working on these pieces, I’ve learned something and expanded my working methods.

In almost every, case these pieces have always been the most popular and the most “Wow!” paintings in my portfolio. Picasso said a studio should be a laboratory.

I think shows like BIG can be a way to experiment with new ideas and techniques. Who knows? You may stumble across a way of working that may change your artistic career.

You have been to the Bologna fair on several occasions. How has your experience of the fair changed over the years?

I’m not sure that my experience has changed that much. But that’s not to say I’m bored!

It’s always exciting to see what’s being published around the world. I expect to see new things and I’m rarely disappointed. Of course digital publishing has grown since I started going to the book fair so it’s much more influential.

Through the years I’ve met more editors, art directors and illustrators so I know more people and it’s always fun to renew old friendships. And, of course there are the restaurants that I go to on a regular basis.

Over the years I’ve become friends with one of the owners. Now,

that's really exciting!

What are your "must-do's" when you are there? It can be overwhelming for a first timer. My suggestion is to wander around and “absorb” what you see, not seeking out anything specific. Take notes, jot down what strikes you.

If you open yourself to everything, you’re guaranteed to see something you would have missed if you were focused on a certain goal. I love wandering the “foreign” stands (foreign to this American, at least). There is so much creativity happening all over the world. I confess, working mainly in the American market, it’s easy to become too provincial in my thinking.

Any first time fair attendee should see as many books in as many stands that are

not her market. It’s a real inspiration.

Also, as a “must-do”, I try to make a trip to Florence, only 40 minutes away by train. It’s every artist’s heritage, birthplace of who we are. It’s a lovely town chockablock with history and art (with some nice markets and restaurants!) It’s well worth a day off from the fair or staying the extra day.

Will you be in Bologna in April? Definitely plan to go. I missed it last year and feel the need to return.

Will you be participating in the ever-popular Dueling Illustrators event at the SCBWI booth? Yes and it’s always great fun. In past years I was teamed up with

Paul O. Zelinsky, which is always a great thrill, and honor.

Thank you Doug! I look forward to seeing you in Bologna in April.Cynsational Notes Elisabeth Norton grew up in Alaska, lived for many years and Texas, and after a brief sojourn in England, now lives with her family between the Alps and the Jura in Switzerland.

She writes for middle grade readers and serves as the Regional Advisor for the Swiss chapter of the

Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators.

When not writing, she can be found walking the dogs, playing board games, and spending time with family and friends. Twitter:

@fictionforgeThe Bologna 2016 Interview series is coordinated by

Angela Cerrito, SCBWI’s Assistant International Advisor and a

Cynsational Reporter in Europe and beyond.

|

| Photo by Peter Nash |

By

Patti Bufffor

SCBWI Bologna 2016and

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

CynsationsSusan Eaddy works in her attic studio writing picture books and playing with clay. She was an art director for fifteen years, during which time she won international 3D illustration awards and a Grammy nomination. She lives in Nashville, Tenn.; and is the regional advisor for the Midsouth chapter of SCBWI and a co-organizer of the SCBWI Bologna Book Fair. Her illustrated books include Papa Fish’s Lullaby by Patricia Hubbell (Cooper Square, 2007) and My Love for You is the Sun by Julie Hedlund (Little Bahalia, 2014). Her latest picture book, Poppy’s Best Paper, was released by Charlesbridge in July 2015. She loves to travel and has used the opportunity to do school visits anywhere in the world from Taiwan to Alabama to Hong Kong and Brazil.Hi Susan! Thanks for participating in the 2016 SCBWI Bologna Book Fair interview series.

With much more focus on diversity in children's books than has been in the past, how important of a role do you think book fairs like Bologna play in introducing young readers to children from other countries and cultures?I think that book fairs like Bologna offer hope and understanding for our future. It creates the opportunity to come together from all over the world and find common ground in stories.

Children can only benefit from books translated into their native language to both learn about new cultures or to find that other cultures are very much like their own. With this experience, they see that kids from all over have similar feelings and experiences.

Any tips for new visitors to the Bologna Children’s Book Fair?First of all, the

SCBWI booth is your hub, and home away from home. You’ll be surrounded by friends you’ve never met before. To maximize your opportunities:

- Apply for a personal or regional showcase with Chris Cheng.

- Schedule portfolio reviews.

- Bring promo materials.

- Read the program.

- Attend the talks.

- Network!

Getting Around: Being the worrier that I am…I like to figure out where I am going via Google Maps the day before I need to be somewhere.

Since wi-fi is not always available on the streets, I take a screen shot of the map I need when I am connected, and can then access it through my phone or iPad photos whether I am connected or not.

Get city and bus maps at

Tourist Info in the Neptune Fountain Piazza. Buy bus tickets there or at the Tabachi (the little kiosk).

Budget Tips: Have breakfast bars with you at all times. There are food stands at the Fair, but they are pricey and packed, and often a breakfast bar will get you though the day. Then you can splurge a bit on the dinner meal.

Some lodging comes with a modest breakfast, but if you have the option of declining breakfast for a price break, do so. You can generally get a cappuccino for much less and chomp on your breakfast bar.

If you have an apartment, buy groceries and make lunches, even some dinners.

But

do eat out when you can. This is Italy! Home of spectacular food. Share a room, a taxi, a bottle of wine.

Do keep all receipts, again, remember this is a business trip.

Those are some great tips. You really are a pro. You’ve done a lot of traveling over the years, China, Italy, and Brazil. As an illustrator, how does seeing different cultures influence you?I love getting a peek at different cultures when I travel, and specifically I love visiting the schools. One of the things that strikes me most, is how universal kids reactions and questions are.

I have had the same questions from kids in Hong Kong as I've had in Brazil. ("How long does it take you? Why clay? How much money do you make?")

Kids' artwork and enthusiasm are so similar in every culture I have seen. And since so much of my presentations are visual, language does not impose a huge barrier.

In 2015, you officially stepped onto the writing side of picture books with the release of Poppy’s Best Paper. First off, congratulations! And secondly, what particular challenge surprised you when you took off your illustrator’s hat and switched it for an author’s hat?Thank you! I have lots of memories and ideas from my childhood.

I began writing because most

art directors told me that my clay artwork was a tough fit for other people's manuscripts and that I should come up with my own stories.

As I began to write, the stories that unfolded were more complex than suited my illustration style, and the irony is that my

own manuscript of Poppy's Best Paper was not a good fit for the clay!

I tried to illustrate Poppy in clay many times, until finally my agent intervened with the suggestion of using another illustrator.

Brilliant!

Rosalinde Bonnet's illustrations made all the difference in the world.

Sometimes a fresh perspective is exactly what the project needs. So glad that worked out. I’m just fascinated by your illustration method of first drawing an outline then filling it in with clay. Do you see the image with color before you begin or is that something that changes as the page progresses? I start with a color palette that interests me, then I explore it further in the computer or with colored pencil, working on top of copies of my original sketch. Often colors are changed a bit in the clay stage, but I try to have the colors worked out before I mix them in clay.

I can imagine mistakes can be costly. After your artwork has been published in a book, how do you preserve it and are you allowed to sell it? I save my artwork in pizza boxes and other flat boxes and have my studio knee wall space filled with them. The sad thing is that if I am using plasticine, it is not a permanent medium and they can never displayed in any way but on a tabletop under glass.

I

do have some framed and saved that way, but I don't sell them. I also use some polymer clay which is more permanent, but I don't sell those either. Since the end product is ultimately a photograph of my clay, I do sell large prints of the work.

Pizza boxes. I love it! What question have you never been asked on an interview or school visit, but wish to be? Hmmmm.... How old do you feel, or rather, what is your mental age?

I think ten years old is the age I identify with most. I

still think like a ten year old. I'm forever trying to figure the world out and gain experiences by feeling my way through while keeping that sense of wonder. I rarely feel like an expert, but in a way that feeds the creativity.

That's actually why I enjoy clay so much, because I don't know how to do it! Every illustration becomes a discovery process. With lots of skills, ten year olds are still trying to do things in their own way with exuberance and angst, and most are not yet jaded.

Ten is my favorite age, too. And finally, what are you working on now? Any surprises you can share with us? I am thrilled to say that my editor and I are working on a new Poppy book! In this second book, Poppy faces sibling rivalry with not one but

two adorable additions to the family.

We'll see if Poppy can learn to share the limelight!

Congratulations! Can’t wait to find out. Thank you so much for stopping by, Susan. I wish you a lovely time at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair. Cynsational NotesThe tenth out of eleven children in a family that took in hundreds of foster kids,

Patti Buff found solitude in reading at a young age and hasn’t stopped. She later turned to writing because none of her other siblings had and she needed to stand out in the crowd somehow.

Originally from Minnesota, Patti now lives in Germany with her husband and two teenagers where she’s also the regional advisor of

SCBWI Germany & Austria. She is currently putting the finishing touches on her YA novel Requiem, featured in the

SCBWI Undiscovered Voices 2016 anthology.

The Bologna 2016 Interview series is coordinated by

Angela Cerrito, SCBWI’s Assistant International Advisor and a

Cynsational Reporter in Europe and beyond.

By

Patti Bufffor

SCBWI Bologna 2016and

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

Cynsations

Kathleen Ahrens was born in the suburbs of New York City and aspired to be an astronaut and to live in a skyscraper. Poor eyesight led her to forgo the first dream, but her move to Hong Kong allowed her to finally fulfill the second.

As a child, she read constantly — often in very dim lighting — leading to her poor eyesight, and she could often be found with a book in one hand and a dictionary in another, now clear precursors of her love of both literature and language.

Her favorite subject in high school was Latin, but her aptitude in math led her to enter the University of Massachusetts Amherst as a computer science major, later switching to a degree in Oriental Languages after she grew bored writing computer programs that mimicked war scenarios.

Currently a professor at Hong Kong Baptist University, where she is the director of the International Writers’ Workshop, she is also a fellow in the Hong Kong Academy of Humanities, and the international regional advisor chairperson for the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. Hi Kathleen! Thanks for stopping by the blog to discuss the upcoming Bologna Book Fair. With much more focus on diversity in children's books than has been in the past, how important of a role do you think book fairs like Bologna play in introducing young readers to children from other countries and cultures? The fact that buyers can walk from one hall to another and see and acquire books from all over the world is very important — without Bologna it would be much harder to know of and gain rights for books from outside one’s own geo-political boundaries.

In addition, while most everything is available on the internet nowadays, it’s still people who connect their friends to books they find at the fair and introduce people who buy and sell rights to each other. These connections happen quite naturally in Bologna, which make it that much more likely that the books from one country may make it to the shelves of another country.

One thing that I’ve noticed as I’ve traveled is that so many publishers in countries outside of the U.S. bring in (and translate) books from all over the world. I’ve yet to see that kind of cross-cultural diversity in U.S. bookstores, even in independent ones, mainly because the U.S. publishers are simply not buying (and translating) that many books from other countries.

Part of that has to do with the fact that US has its own rich publishing environment, but part of it seems to stem from the assumption that U.S. children will not read translated books. This assumption needs to be tested by regularly putting the very best of literature translated from other languages into the hands of readers in the U.S.

Any tips for new Bologna visitors?I highly recommend the museums in Bologna, including the Archaeological Museum of Bologna and Museo d'Arte Moderna di Bologna (Mambo). My favorite is the Museo Civico Medievale because it contains artifacts that show medieval life in Bologna, including funerary monuments and tombs for professors, some of which have engravings that show teachers lecturing to students. Perhaps because I am a university professor myself, I find these representations fascinating, especially as the scene is still a familiar one in universities today.

One tip if you visit the museums: there are audio recordings are very well done and worth the cost of renting if available.

Great tips. I’ll be sure to check them out. Your picture books (Ears Hear and Numbers Do, both co-authored by Chu-Ren Huang, illustrated by Marjorie Van Heerden) are bilingual in English and Chinese and feature an Asian setting. How hard was it to cross both cultures in one project? The challenges for these two picture books was in the language. I like to say I “co-argued” these books with my co-author, who also happens to be my husband.

We were adamant about having the text read naturally in both languages and yet still be clear translations of the other language. So sometimes my husband would come up with a line that sounded great in Chinese, but awkward in English, and vice versa.

Another challenge was that the editor wanted the text and illustrations explained, as she was afraid that the minimal text and illustrations with fantastical elements might be confusing.

This is not something that is usually done in picture books published in the United States, as the reader is free to interpret the text and illustrations as he or she wishes.

We compromised by providing commentary and questions in the back of the books to assist the adult reader in interpreting the text and illustrations. I think it worked out well in the end because it helps parents see that it’s okay to stop and discuss a text during a reading, and that there is no single correct interpretation. For parents who are unfamiliar with reading to young children, or who feel that a book should have a particular overt message, it’s important to let them know that multiple interpretations are fine.

‘Multiple interpretations’, which in themselves are another form of diversity. Very cool. Your other writing projects, including the one that won the Sue Alexander Most Promising New Work Award are more western based. What are some of the challenges of writing for children in your adopted country and writing for your homeland audience? And how do you keep up to date with teens from the other side of the world?The biggest challenge is the same for any audience — namely, getting what is in my head down on paper. I can sit at the computer and see the scene perfectly in my head. I can hear the dialogue and smell the freshly-shampooed hair of a character. But all that needs to be translated to the page and that’s part of the challenge and excitement of writing.

In terms of keeping up with teens in the U.S, I know enough to know that I could never keep up. But I also know that, as Doreathea Brande said, “If a situation has caught your attention…[if] it has meaning for you, and if you can find what that meaning is, you have the basis for a story.”

That’s what I’m doing when I write — I’m finding that meaning. And when someone reads what I’ve written, they’re creating their own meaning based on what is going on in their lives at that particular point in time. So to my mind, it’s not so much keeping up-to-date as being curious and open to meanings in everyday situations and figuring out how they might intersect with universal themes and current issues that are of interest to readers.

You are extensively published in the academic world, which requires a fair amount of research. Do you apply the same research techniques to your fiction? If not, how do they differ?  |

| Hong Kong at night |

In my linguistic research, I set up a hypothesis and then test my hypothesis by gathering linguistic data through experiments or through analysis of linguistic patterns in that corpus.

When I write creatively, I utilize the internet, the public and university library, newspapers, published diaries, etc. in order to get background information for my story — the details that make a scene come alive for reader.

In the former, I’m testing hypotheses; in the latter, I’m gathering information. However, they share a similarity in that I also need to gather information before I test a hypothesis — I need to see what other conclusions researchers have before I start my own research. So I’m pretty good at locating and sifting through information — I used to do this on 3 x 5 inch note cards. Now I use Scrivener and Mendeley to stay organized.

And finally, what are you working on now? Any surprises you can share with us?I’m working on a YA novel about two sixteen-year old half-sisters meeting up at a summer camp for the first time in ten years — one has been waiting for this summer for ages, while the other has been doing everything possible to avoid it.

What’s at stake is not only the relationship between the two of them, but also the main character’s relationship to her mother, who left her at an early age and later died while serving in Iraq.

That sounds amazing – and powerful. Hope to be able to read it soon. Thank you so much for stopping by, Kathleen. I wish you a lovely time in Bologna. Cynsational NotesThe tenth out of eleven children in a family that took in hundreds of foster kids,

Patti Buff found solitude in reading at a young age and hasn’t stopped. She later turned to writing because none of her other siblings had and she needed to stand out in the crowd somehow.

Originally from Minnesota, Patti now lives in Germany with her husband and two teenagers where she’s also the regional advisor of

SCBWI Germany & Austria. She is currently putting the finishing touches on her YA novel Requiem, featured in the

SCBWI Undiscovered Voices 2016 anthology.

The Bologna 2016 Interview series is coordinated by

Angela Cerrito, SCBWI’s Assistant International Advisor and a

Cynsational Reporter in Europe and beyond.

Someone once told me that I was restricting myself as a storyteller. I don’t believe I am.

Someone once told me that I was restricting myself as a storyteller. I don’t believe I am.