By Anatoly Liberman

Henry Bradley, while writing his paper (see the previous post), must have looked upon Skeat as his main opponent. This becomes immediately clear from the details. For instance, Skeat lamented the use of the letter c in scissors and Bradley defended it. He even noted, in the supplement to the paper devoted to Spelling Reform, that, all Skeat’s ardor and arguments notwithstanding, in his publications and personal letters he stuck to traditional spelling. This mild taunt was beside the point. Why should Skeat have adopted reformed or simplified spelling before it became the norm?

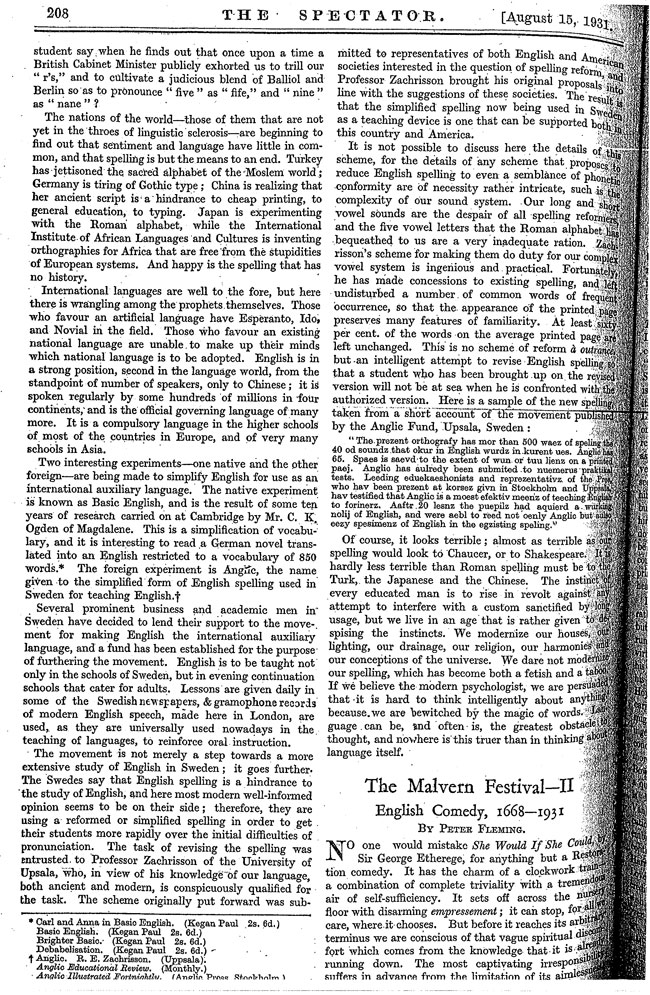

Skeat’s program paper was delivered in 1906. In modern times, the proposal for simplified spelling was first made in 1881, and the decade before the First World War witnessed an unprecedented and never to be repeated splash of interest in this matter. In the United States, some linguistic journals agreed to print papers with the words having the appearance favored by the reformers. George O. Curme, a distinguished American linguist, published a scholarly article in a leading German periodical using “new orthography” (1914). I needn’t remind anyone that this was the epoch of Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency, hence the numerous cartoons connecting him and the Reform. In 1910 George B. Shaw believed that England would move toward phonetic spelling in the foreseeable future. Foreign scholars, especially in Sweden and the Netherlands, clamored for action, and offered recipes. English, they pointed out, had become an international language and its written form was the greatest handicap to those who wished to learn it.

The most timid attempt at Spelling Reform

The war made all such problems irrelevant. Then came the Bolsheviks and the Nazis and another war. In later times, the Chomskyan revolution did a lot of harm to the “cause.” Chomsky’s emphasis on the historical logic of English spelling contributed to the loss of the little enthusiasm scholars might have for Spelling Reform. He taught that one has to distinguish between underlying forms and surface realizations. Archaic English spelling provided Chomsky and his closest ally Morris Halle with a treasure trove of “underlying forms” (for example, we spell take, and the underlying form has “long a,” that is, the vowel of Modern Engl. spa, father, etc., and it is exactly this vowel from which the modern diphthong developed). In that academic battle, Bradley won a decisive victory, a fact to be regretted.

Skeat’s paper runs to eighteen pages. His main point, so cleverly contested by Bradley, is predictable: letters should represent sounds, but English spelling fails to do so. Very funny from our perspective is his suggestion for explaining to boys (naturally!) the true value of English vowels. The English should give up their habit of Anglicizing Latin pronunciation, and, once the boys begin to read Latin approximately as they would read Italian, they will understand the nature of sound change, and it will be easier to explain the correlation between letters and sounds, a major prerequisite for the success of the Reform. Alas and alack, today this recommendation has little value: our “boys” no longer study Latin for six years.

Help from Abroad

One of the pioneers of Spelling Reform was the great philologist Henry Sweet, and Skeat supported his ideas. These are the spellings both of them advocated: hav, liv, abov; agreev, aproov, solv, freez, etc. (in the e-less category, only adz and ax gained a foothold, and only in American English); jepardy, bredth; acheev, beleev; cumfort, tuch, cuzin; flurish; batl, ketl, writn; lam, num; lookt, puld; honor, labor (once again the last words will not offend the American eye). Skeat referred to two great gains the Reform would have. The first strikes me as almost humorous, even though offered in dead earnest, the second as vital.

“The first is that those partial reforms would necessarily involve the disuse of a large number of useless letters. In this way more matter would be got into a page, and some labour in the compositions of the type would be saved; and as this would happen in every case, …it might very easily save every printer and publisher a considerable sum of money. It would not be surprising if the aggregate savings, in the course of a year, throughout the British Empire, were to amount to a considerable sum of money. [He projected the economy of thousands of pounds.]… The second is that the task of learning to read would be considerably simplified, and the time taken to achieve that task would be considerably shortened…. In this case there can be no doubt at all that the sums thus saved would be very considerable.”

He devoted several paragraphs to beating this willing horse.

Skeat summarized the situation quite convincingly: English words have turned into hieroglyphs that have to be learned mechanically. With this spelling we are not quite in China (figuratively speaking), because many words are still spelled phonetically, but we are halfway through (I am paraphrasing, not quoting Skeat). Close to the end of the paper he admitted that since 1881 absolutely no progress had been made in reforming English spelling. Publishers and journalists crushed every attempt to tamper with the existing system (“I speak it to our utter shame,” he added). But his explanation of the reasons for the failure is probably wrong. He ascribed the public’s near universal resistance to its ignorance of the most basic facts of linguistics. The obtuseness and ignorance of his countrymen was one of Skeat’s favorite subjects; he had no patience with human stupidity.

However, in this case, it was probably not only ignorance that killed the Reform. We should rather consider the natural wish of human beings to protect their riches, be it material possessions or spiritual property. Someone who has learned the spelling of the noun occurrence (very few have, as far as I can judge), has perhaps been whipped, rapped over the knuckles, or received bad grades for spelling it with -ance or with one r (or one c), will cling to the hard-obtained treasure like grim death. To waste years on such terrible words and give up their spelling? No! Besides, in England honor, labor, ax, and their likes had the stigma of being Americanisms. Who would fall so low as to imitate the Americans? Even after 1918 British periodicals carried blood curdling letters to the editor about the corrupting influence of Americanisms on pure English.

From this point of view, it is curious to read the concluding paragraph of Skeat’s paper.

“If, however, it should come to pass that a real Spelling Reform should previously be effected in America, it may quite possibly be a gain to us; because the history of our language is there more generally known. I lately met with the President of an American university, who said to me (I have no doubt with perfect truth) ‘In our universities English takes the first place’. This is one of those facts of which the ordinary Englishman is entirely ignorant; indeed, it is almost impossible for him to imagine how such a state of things can be possible. I recommend the contemplation of this astounding fact to your serious consideration.”

I am a great fan of Walter Skeat’s and often try to placate his irascible shadow. This time I hasten to reassure the great man that English no longer takes the first place in American universities; at all stages, we teach concepts and critical thinking, not facts. We despise memorization and encourage discussion, ideally group discussion following a PowerPoint presentation. One semester of the history of English is rarely required even of English majors, and for spelling we have spellcheckers. However, it is not good to finish even a grim comedy (that is, a drama in which the protagonists don’t die) on a gloomy note. Perhaps indeed, the stimulus to reform English spelling will come from America; we’ll see. The past is hard to reconstruct, but the future is even harder to predict.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

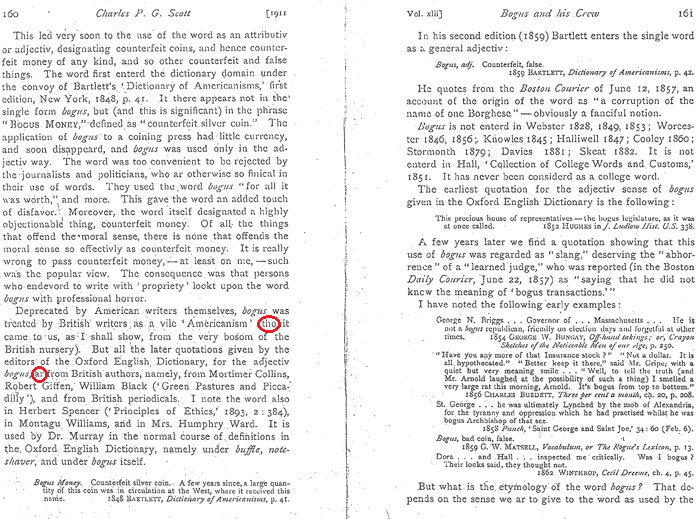

Image credits: (1) Printed in 1911 in the American Transactions of the Philological Association (part of the article by Charles P.G. Scott “Bogus and his Crew”; Scott was the etymologist for The Century Dictionary). (2) A sample of what the Swedes suggested (the Anglic Fund, Uppsala). Both images courtesy of Anatoly Liberman.

The post Walter W. Skeat (1835-1912) and spelling reform appeared first on OUPblog.