new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: clementine beauvais, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 11 of 11

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: clementine beauvais in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

‘The ink was in the baby, he was bound to write a tale

So he wrote the first of stories with his little fingernail’

Nathalia Crane was nine years old when, in 1924, she wrote ‘The First Story’ and many other poems, published in a collection called The Janitor’s Boy. She was one of many child poets in the 1920s, which saw a spate of precocious poetry and prose in the UK and the US. In the 19th century already, a cult of poetic precocity in children had erupted with the rediscovered works of Marjory (/Marjorie) Fleming, a little Scottish girl who wrote everyday from the age of six and conveniently died before she was nine, in 1811 - embodying forever the vision of glorious, pure and doomed childhood genius for the Victorians (this is a great article on the subject).

|

| a rather haunting sketch of Marjorie Fleming by (?)Isa Keith |

I’m currently looking at those works by child poets and at the adult discourse which developed around them, and it’s fascinating to see the extent to which such works were simply not allowed to be on their own: they were relentlessly explained, explored, excused, by the adults who read, published and critiqued them (another great article). We get, of course, the usual amount of ‘how cute they are!’, and the associated Romantic claims that they were ‘close to nature’, ‘close to God’, ‘close to universal truth’. Not coincidentally, references to classics of children’s literature recur when critics analyse those poems: they talk of Alice in Wonderland and Rudyard Kipling, and James Matthew Barrie prefaced a novel by nine-year-old Daisy Ashford. This was around the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of children’s literature, at a time when children and childhood already had cult status; the verbal abilities of the precocious poets gave hope that their word might be interpreted, and ‘teach’ adults about the beyondness to which childhood supposedly had access.

But those poets were also thought of as dramatically unstructured and lacking technical skill. In 1926, an academic reviews ‘some child poets’ and gives Marjorie Fleming the kind of review anyone would cringe to see written about oneself:

‘An affectionate little soul, with a real joy in nature, and a strangely precocious taste for books, she found her surroundings prosy, though her heart expressed itself in bursts of pitifully inadequate song.’

He goes on to expose Marjorie Fleming’s ‘limitations’ by indicating that she often invents words to make up for a lack of rime (heaven forbid!) and:

‘Another shift which she found useful was the introduction of a purely irrelevant line:

At supper when his brother sat

I have not got a rhyme for that.’

Purely irrelevant indeed. Thankfully, George Shelton Hubbell reassures us that young Shelley was also a ‘juvenile blunderer’ in matters of poetry.

A strong concern of much of the general audience at the time was whether the children were actually writing those poems, or if adults were sneakily doing so. A passionate correspondence developed in Poetry: A Magazine of Verse in 1919, concerning little Hilda Conkling, who dictated poems to her mother:

‘Dear Poetry: Could you not give your readers more explicit information as to just how those poems of Hilda Conkling’s are done: To what extent does her mother select, rearrange and give form? Is it all actually improvised as given?… What a delightful little genius!… (E. Sapir.)’

‘I do not change words in Hilda’s poems,’ replied her mother, ‘nor alter her word-order; I write down the lines as rhythm dictates. She has made many poems which I have had to lose because I could not be certain of accurate transcription.’

The ‘accurate transcription’ of childly thoughts, the ‘authenticity’ of the child’s poetry needed to be ascertained at all costs, to the extent that Nathalia Crane, perhaps the most controversial of all child poets, was asked to produce a poem in the same room as a journalist.

Nathalia Crane was quite unique in that her poetry got published in a newspaper without the editor’s knowledge that it was a child’s. The editor, Edmund Leamy, wrote an afterword to her collection, in 1924, in which he talked about his astonishment when he discovered the ‘imposture’:

My surprise is excusable. So many times I had received “poems” from youngsters who were careful to give their ages in addition to their names; so often I had received visits from doting parents or relatives requesting publication of verses by their children or sisters or cousins that I never dreamed any child would ever submit any work from his or her pen without adding the words “Aged — years”. But little Nathalia was the exception — and there was nothing in her poems that I received to indicate her age. The poems bought were accepted on their merits and on their merits alone.

‘On their merits alone’, with no ‘child-loving’ bias (to quote Kincaid’s famous study); this was, therefore, proper poetry. Yet it made adults feel relentlessly uncomfortable. Her poetry was more structured, more sexualised and more aware of the constraints of the adult world than other child poets, and adults didn’t know how to tackle it. Louis Untermeyer, in 1936, prefacing Crane’s new collection ‘Swear by the night’ (she was 22 by then), talks about the uncanny feeling he had when the poet was a little girl: ‘She was ten and a half years old and she puzzled me. She puzzled me as a person even before she puzzled me as a poet. … There was even then a queerness about her, an almost too pronounced childishness coupled with a curious vocabulary.’

The blending of categories is always troublesome, the difficulty to draw lines between adulthood and childhood always a problem. Adults then, but still now, find it difficult to make sense of moments when the presence to the world of children is felt literally, fully, rather than wrapped in layers of symbols.

Nathalia Crane died in 1998 and I’ll leave you with one of her early poems, because it’s fair, after contributing myself to obscuring the works of those child poets with my own, to let her have the last words. I think the work might still be under copyright, so I'll only put the first stanza here; click to redirect to her collection on the Internet Archive.

LOVE

_____________________________________

Clementine Beauvais writes in French and English. She blogs

here about children's literature and academia.

If you're reading this post in the morning of the day it's come out, send me a positive brain wave and cross your fingers for me: I'm currently shaking fretting panicking calmly getting ready for a job interview in a university somewhere in the UK...

So I'm taking this blog post as an opportunity to reflect on the difficulties and joys of having another job in addition to writing, one that you really don't want to give up on. Most people tend to assume that I'm secretly dreaming of being a full-time writer. I often hear, 'Are you keeping up the academic side just for the money?'

That's easily answered in MS Paint:

To most people, if you have an 'artistic' side, anything else you do must surely be 'paying' for your artistic activity. If you're not giving up the 'day job', it probably means the artistic one doesn't earn you anything, or not enough.

Even my academic colleagues have somehow internalised the notion that I would 'prefer' to write children's books as a full-time job; that it's what I

really want to do. We were talking at lunch about what we'd do if we won the lottery (

yes, students: that's the kind of thing your lecturers and tutors talk about at lunch), and several colleagues said that they'd quit their job immediately. I said I certainly wouldn't stop working - I like my research and teaching, and I'd get bored. The immediate response was, 'But you could spend all the time you want on writing your children's books!'

Frankly, if I really wanted to spend all my time writing children's books... well, I would take the jump and do it.

And if I needed a job to subsidise this activity, I probably wouldn't opt for one that requires hours of teaching, reading, essay-marking, meeting-going, networking, jargon-deciphering, revise-and-resubmitting, email-sending at two in the morning, in a crazy incertain job market, with no weekends to speak of, holidays that are in fact conferences, and the absolute impossibility to stick to regular hours.

Well then, are you keeping up the academic job as a safety net, 'just in case the writing doesn't work out?'(The notion of academia as a 'safety net' is just... I mean, I wish, but...)

If the writing didn't 'work out',

it would probably be in part because of the other job. Writing success isn't some esoteric thing that does or doesn't work out according to the unpredictable movements of the stars - the more you work on it, the more likely it is to 'work out'. You might never be J.K. Rowling,

but you can get very respectable sales by being strategic, working hard, meeting children and promoting your books. This is more difficult when you've got another job.

So of course,

having another job isn't ideal for your publishers, agents and publicists. There is definitely faint pressure to 'quit the day job' and be a full-time author. School visits and festivals often happen during the week. Even if you can make some of it, you can't be one of these writers who do school visits all the time. Therefore your books might not sell as well, and you might not get as high an advance next time, or even asked for another book.

Gone are the days when it was acceptable to write your books in your 'free time', and to decide that this year, you'll only publish one, or none. It doesn't work like that in the UK (to a degree, it still does in France). The publish or perish rule applies here like it does in academia; being a part-time writer will always put you at a disadvantage.

Implicitly, there is pressure also from other authors and illustrators who are full time.

There's a very legitimate worry that writers like me contribute to making our activity appear unprofessional, amateurish, dilettantish, something you do 'when you've got the time', or if a partner is subsidising your indulgent bohemian bourgeois lifestyle. I entirely understand this concern, and it does bother me that I contribute to this vision. Authors and illustrators should absolutely be in a position to live - and to live well - thanks to their work.

Saying that your writing brings you 'pocket money' or is 'a fun thing on the side' is quite insulting to the rest of the community.But choosing not to choose is perhaps the only authentic option when you have the luxury of having two activities that bring you different rewards, different challenges and different joys. And many people, I'm sure, secretly want to do

not just one thing, but

several. Recently a student asked me for career advice (I know, terrifying). She said she was split, because she wanted to be a film maker, but 'not just': she was also considering being a researcher in psychology, or perhaps a teacher, or even a consultant. Why can't we do several things at the same time, when we have so many interests?

I agreed of course, but said the reasonable thing: doing several jobs, especially an artistic one and another 'official' one, is difficult. She said 'Well, you manage it!' I told her 'managing' was a strong word - she doesn't see the moments when I'm marking essays all evening before updating my PowerPoint for a school visit the next day, or playing Google-Calendar-Tetris with deadlines on fiction-writing and article submissions and conference abstracts and book edits.

Since I was making it sound like my life was only slightly less sinister than that of the Baudelaire orphans, she blurted out:

'But you're happy, aren't you?'. I had to admit that I am...

_____________________________________

Clementine Beauvais writes children's books in French and English. She blogs

here about children's literature and academia and is on Twitter @

blueclementine.

Today, three stories, followed by a few thoughts...

Story 1. The hole.

In my parents’ building in Paris, where I spent most of my childhood, there’s a hole in the wall near the ground - a hole big enough for a child to crawl through, and as a child I would always do so instead of using the door. Most of the time I’d already wriggled through the hole before my parents had found their keys - and I’d open the glass door from the inside, extremely dusty but very conscious of my power.

As time went by, I somehow stopped crawling through the hole.

One day, when I got home from school, I realised I’d forgotten my keys. No problem, I thought, I can just go through the hole. But of course when I tried I couldn’t - it was too narrow for my shoulders.

It didn’t make me sad. But for some time afterwards, when I thought about it, I confusedly wondered - was it really because I’d grown too big for it that I couldn’t go through the hole anymore, or was it because I’d stopped going through the hole that I’d grown too big for it?

Story 2. The spatula.

As a child I was constantly, voraciously hungry. I would actually dream that I was eating roast chicken with cream, or Nutella crêpes or cheese. Only pride would prevent me from crying if I had any reason to believe that another child, or indeed adult, had been given more food than me. I couldn’t focus on anything if there was a vending machine in sight, especially if it sold Kinder Bueno, my favourite chocolate bar and an absolute torture, as I was always divided between the desire to eat each chunk in one go and the temptation to open them up like little boxes and lick the cream inside.

I had a friend whose mum made excellent cakes every day. I often stayed with them on holiday, and my friend and I would prowl like vulture around the kitchen table as her mum finished scraping the dough out of the mixing bowl and into the cake dish with a spoon. Then we’d fight furiously over the remnants of dough in the bowl, with fingers, tongues and chins.

One day, her mum bought a silicon spatula. I’d never seen a silicon spatula before.

We watched in horror as the ruthlessly efficient implement left barely a trail of cake dough in the mixing bowl. Every day after that, we swallowed back tears, and I clearly remember my head spinning with frustrated desire, as increasingly spotless mixing bowls ended up in the sink to be washed. We prayed and implored my friend’s mum to leave us at least a tiny bit, but she was under the impression that it was less useful to us raw than baked.

We devised the perfect crime: we pushed the spatula all the way to the bottom of the cutlery drawer and it fell behind it, and behind the freezer beneath the drawer, with a satisfying CLACK, joining dozens of lost spoons, scissors and other expatriates from the overfilled drawer.

For the next few days the wooden spoon returned and with it the minutes of bowl-licking. Then they bought another spatula.

Story 3. The castle.

My mother was pregnant with my sister; I was five and a half years old. We had an absolutely tiny flat in Paris and my parents were looking for a less absolutely tiny flat. I knew how much they wanted to spend on it, and I ‘helped’ by looking at ads in the windows of estate agencies.

Suddenly I spotted an ad for a castle, a castle, for sale at a much lower price than the one my parents were ready to put into the new flat. It had turrets, an immense garden, a forest.

I listened, without understanding, as my mother explained that they didn’t want a castle, because they wanted to live in Paris. I pointed out that the ad said that it was only half and hour from Paris. My mother laughed and said no, Clementine, listen, we’re not buying a castle. We’re buying a flat in Paris.

I remember thinking, distinctly and with real alarm, feeling that this realisation would have an enormous impact on my future life: my parents are mad. I live with people who are mad.

***

I have three silicon spatulas now, and when I finally get a permanent job I will likely buy a small house or a flat. Not a castle.

It was ‘us’ children versus ‘them’ adults once upon a time, and now it’s the opposite. They’re really not like us, are they? I’m just not that hungry anymore. Sure, the memory of that hunger prevents me from getting too annoyed at them when they steal bits of mozzarella from the salads before they get to the table (arrghh!!!), or when they fly into a tantrum for an ice cream.

And I think it’s amazing that I once wanted a castle. Amazingly mad.

Don't you think?

It would be possible to write children's stories from all those intense memories, and to write them as if we truly believed that castles should indeed be bought and that cakes should preferably be eaten raw. But would it be true? Would it be honest? We don't... do that anymore.

Would they be our stories now, these nostalgic recollections?

How do we write for children, having changed so much?

Do we want to sound, when we write, like we're imagining that we can still go through the hole? That would leave our whole bodies behind, and what made them grow...

_____________________________________

Clémentine Beauvais writes books in both French and English. The former are of all kinds and shapes for all ages, and the latter humour and adventure stories with Hodder and Bloomsbury. She blogs here about children's literature and academia and is on Twitter @blueclementine.

I know I am, in many ways, in support of what in Britain would be qualified as ‘traditionalist’ educational practices in terms of literacy (and in France as ‘normal’ ones), namely the learning of poetry by heart, the imposition of reading lists, etc. However, where I differ from the French view on literacy, and perhaps from many educators in English-speaking countries too, is that I am opposed to the common hierarchy between arts or media which puts reading at the top. I don’t think there’s any reason, once literacy skills have been acquired of course (and it’s not an easy task), to enforce the notion that books are ‘better’ intrinsically than films, video games, TV series, and other visual or musical art forms and media. But they are, certainly, different ways of looking at the world.

This is partly why I’m getting increasingly uneasy with the common claim, in author interviews, that ‘we’ authors ‘now’ have to ‘compete’ with ‘films, video games, TV series’ in order for our books to be read. I used to say this as well, and of course I understand that in the most basic sense of ‘competition’ (=available time), it is true: children and young adults ‘now’ have immediate access to a wide range of such other media, and while they’re watching films or playing games they’re not reading our books. So, in terms of time, yes, we have to ‘compete’. We also have to ‘compete’ with one another, as authors, I guess. We have to ‘compete’ with funny YouTube videos, too, but that doesn’t keep me awake at night.

No, this claim bothers me because I do not see and do not want to see other creative people and other works of art as ‘competition’. Films and video games are not our enemies. They are works that ambition to set in motion creative processes, to stimulate the imagination, to increase empathy, to entice viewers and players to take part in the elaboration of complex worlds, and that can do so in different ways and just as well as books. They are not ‘competitors’. If anything, we complement one another; we provide different ways of encouraging creative, thoughtful, witty, etc. visions of the world.

Saying we’re in competition with them is the equivalent of saying that all these different works of art and ways of looking at the world are interchangeable. ‘Yes! I win! She’s reading my book instead of watching a film!’. To me, this is like saying, ‘Hurrah! She’s reading my book instead of talking to her grandmother!’. Both are hugely beneficial activities. They’re not the same, but they all contribute to growth, maturation, creativity and learning, in their own original ways.

If we try to 'compete' with films or video games through similar narrative strategies, we risk making it sound like literature does not have its own specificities; like it's just a matter of being 'more entertaining' than 'other media'. This would impoverish greatly what we can do with verbal narrative, with words, which are what makes our medium unique.

And there's worse. While we’re busy saying that other branches of the creative world are ‘competitors’, we’re not talking about those branches of the culture industry which are actually busy ‘competing’ with us - in the sense that they're waging a war on the creative spirit and critical thinking of children by promising them, for instance, that the acquisition of a toy or product or game will bring happiness; by flattening the beautiful diversity of existence into easily-packaged, formulaic tales that will generate addiction and therefore money-spending; by constructing consent for the world as it is and driving reflection out of it. That's what keeps me awake at night, to be honest.

I'm being wilfully provocative here, but let me tell you what I see as competition. 10 million iPhones 6 sold in one weekend: that’s competition. Cultural products that are only created so as to sell spin-offs and merchandise: that’s competition. Little girls being made to worry about their looks and having to spend time investigating diets and make-up techniques: that’s competition. Little boys having to be interested in porn and war rather than in creative pursuits: that’s competition. Adverts selling children and young adults a unified, unimaginative version of world where “possession = happiness”: that’s competition.

Thank goodness there are people who create enticing, challenging, thought-provoking, original pieces of work in all the arts and media; and a school system which is starting to recognise this when it encourages high-level visual literacy, film and video game analysis, encounters with media and art forms from different cultures, etc. The real competitors are the messages we receive daily (and especially children) that discourage such imaginative pursuits and critical reflection by giving easy answers to complex questions.

_____________________________________

Clémentine Beauvais writes books in both French and English. The former are of all kinds and shapes for all ages, and the latter humour and adventure stories with Hodder and Bloomsbury. She blogs here about children's literature and academia and is on Twitter @blueclementine.

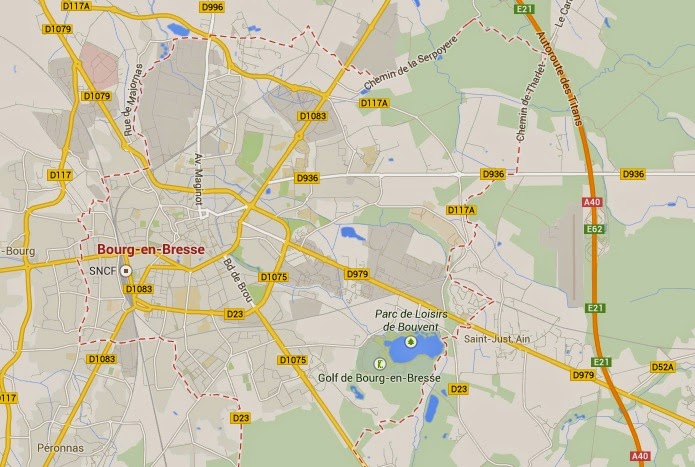

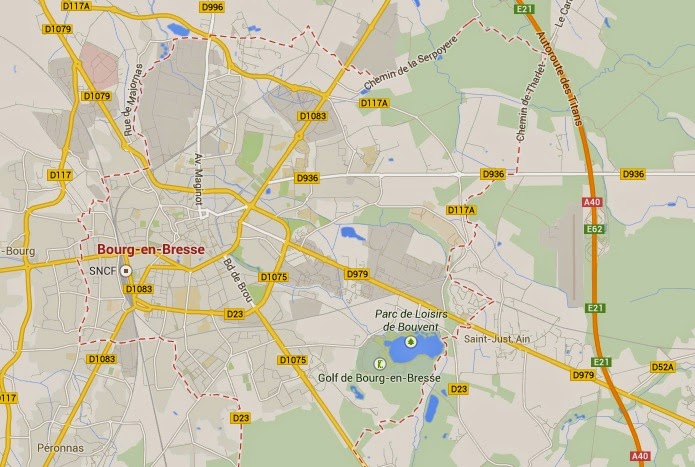

Over the summer I finished the first draft of my next French YA novel, which, in stark contrast to the ones before, is not grim and dark but comical and light. And while my first two YA books take place entirely in Paris - and in places I know very well, including my old high school - this one narrates a road trip between the city of Bourg-en-Bresse (just a few kilometres from South Burgundy) and Paris. I know Bourg-en-Bresse and Paris well, but not the places in the middle, through which my three heroines were cycling. And that's where Google Street View comes into play.

|

| somewhere in France |

Using Google Maps and Google Street View to write books is something I've done for quite some time, and I'm sure that most writers do it, though I hadn't quite realised how weird it sounds to people who aren't writers. My mother told me the other day, quite astonished, that she'd heard a famous writer say on the radio that he'd used it for his own novel, which is entirely set in a place in the US that he's never been to. My own response was a blasé 'Well, yes, of course. What's surprising about that?' Google Street View in one tab, Wikipedia in another, the city/ village website in a third, and more tabs containing blog posts or articles on the places in question: normal set-up for any writing session, no?Surely that's a good enough alternative to an expensive flight for the non-New-York-Time-bestselling author...

Well, sure, most of us would always privilege going to the real-world places, and some writers would not dream of writing about a place they'd never visited. There are obvious issues of cultural sensitivity at stake - 'would I truly respect the place, understand it, if I've only seen it through a 360° camera strapped to a car?'. There's the temptation of information overload, at the risk of ending up sounding like Jules Verne. And of course there are issues about the fact that the material given is exclusively visual, sacrificing the characteristic noises and smells which give life and texture to a place. A lot of writers would thus probably say that Street View should preferably be used only for quick fact-checking after seeing a place IRL (In Real Life).

|

| not the most inspiring portrayal of space |

But maybe there's something specific, and not necessarily inferior, to writing about spaces that you know only from Street View, in exactly the same way that doing a painting from a photograph is different, but not necessarily inferior, to painting from life.

Ideally, painters begin with life-drawing; and similarly, as writers, we would already have written about spaces that we know intimately: we've had, so to speak, considerable training in 'life-writing'. In the most restricted sense of 'write what you know', this is the first skill to master as a 'representer' of things, whether verbal or visual. But of course 'write what you know' is underscored by the problematic assumptions that 1) we 'know' things, 2) we 'can' write those things that 'we know' and 3) even if both of the above are true, it makes for good artistic 'representation'.

Enter Google Street View, which presents a relentlessly artificial, 2D, unknowable vision of space. Just as photographs flatten reality and necessarily restrict the painter's visual and sensory navigation of the object to be represented, writing from Street View means subjecting yourself to an already mediated, stiff and alienating representation of space. How could anyone possibly argue that can be a good thing?

Because, in both cases, it alerts the painter or the writer to the fact that the material cannot possibly provide a truthful kind of 'knowledge' about the object at all. Therefore it becomes not just desirable but absolutely imperative for something more to emerge - a stylisation, an appropriation of the object or the place. And this process comes from a source material so limited, so other, that you can't revert back to things you think you know.

In other words, you just can't ignore, when you're writing a place from Street View (or indeed any travel guide book, like Verne used to do), that your vision of it is absolutely untrue. You just know you don't know it enough to write authentically about it; therefore, the only way you can go is towards further imagining that place. You have to make these impersonal snapshots of roads and monuments somehow become part of an authentic-sounding world. What must it smell like, this little pond on the side of the road? What must it feel like, this avenue, in the summer?

This creative distance is necessary anyway to any writing about place, whether or not you've been there, lived there, or not at all. You might feel you know your house, your street, your city, but of course your vision of them will always already be mediated - by yourself. The troubling difference, with Street View, is that someone else (someone totally faceless, nameless and in fact quite uncannily threatening) has done the mediating for you, placing you by necessity in a position to notice your alienation from this place.

Writing place 'from Google Street View' is of course not the only way we should proceed - that would be an absurd claim - but it can be a very refreshing endeavour in its own right - and a welcome process of distance-taking from 'truthfulness' in writing.

_____________________________________

Clementine Beauvais's space is split between Britain and France. She writes books in French of all kinds and shapes for all ages, and in English humour/adventure series, the Sesame Seade mysteries, with Hodder, and the Holy-Moly Holiday series with Bloomsbury. She blogs here about children's literature and academia and is on Twitter @blueclementine.

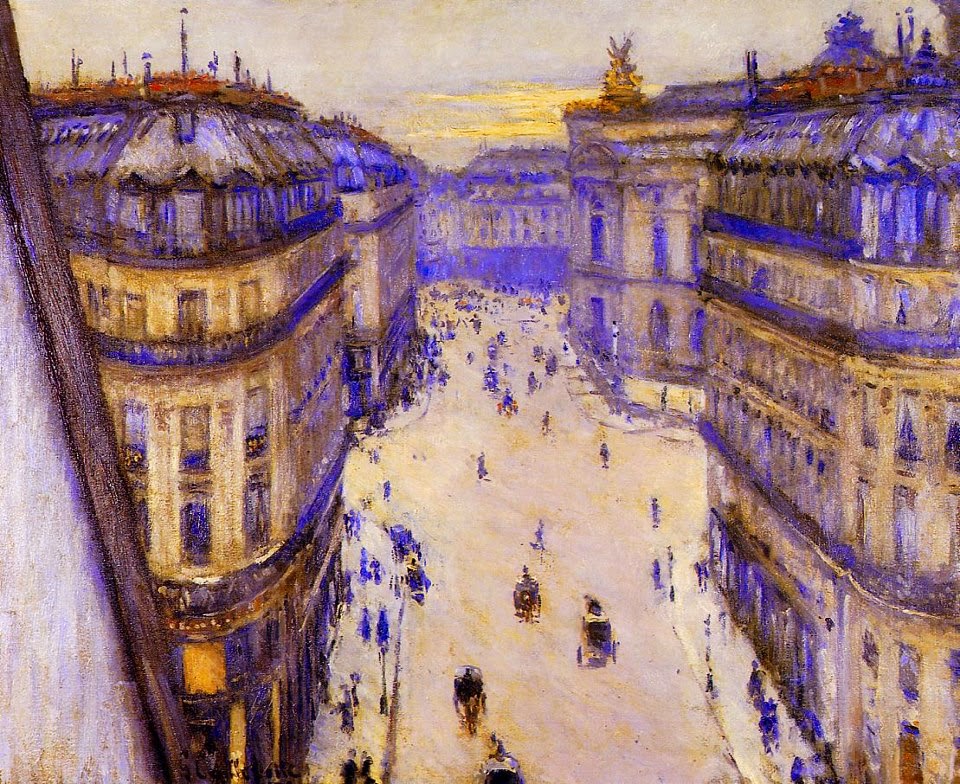

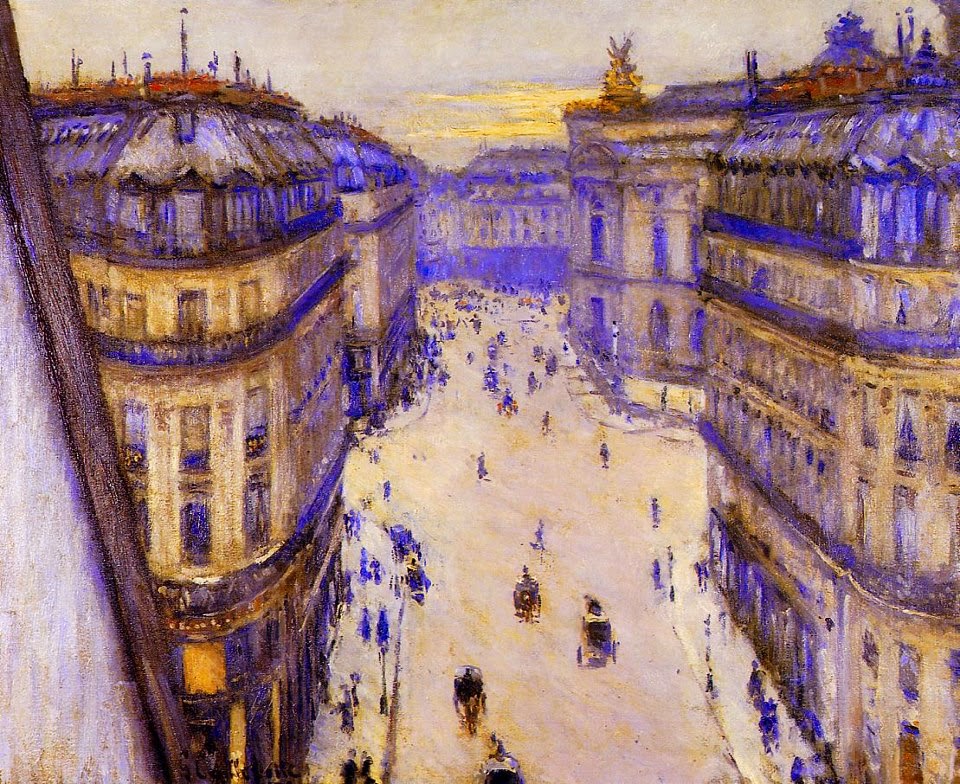

This passage from Kate Rundell's gorgeous Rooftoppers always makes me think of an impressionistic painting:

Paris lay still below them. From where Sophie stood, with both her hands wrapped round the neck of a carved saint, it was a mass of silver, except where the river shone a rusty-gold colour in the lamplight. (p.224)

The way she adds the 'rusty-gold' to the 'mass of silver' - what a lovely contrast of warm and cold metals... and look at those tiny yellow specks from 'the lamplight', which you can just see, can't you, on the surface of the Seine?

I love the fact that it's a child seeing all this from above, from a place that people generally don't go to, and that she's there with her arms hugging a stern, stone figure - as if trying to give it the affection it's never had. For me, it's this painting:

|

| Gustave Caillebotte, Rue Halévy (1878) |

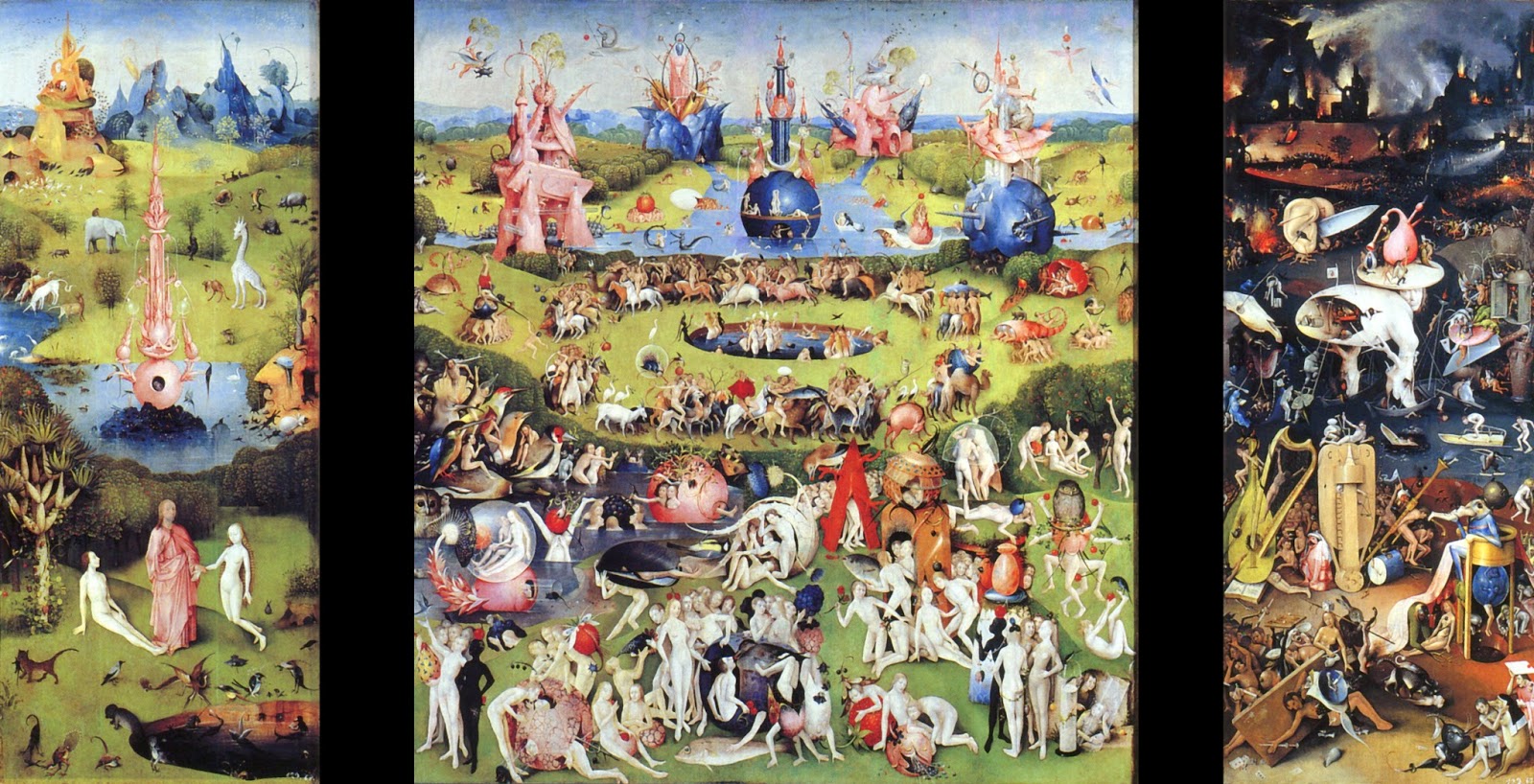

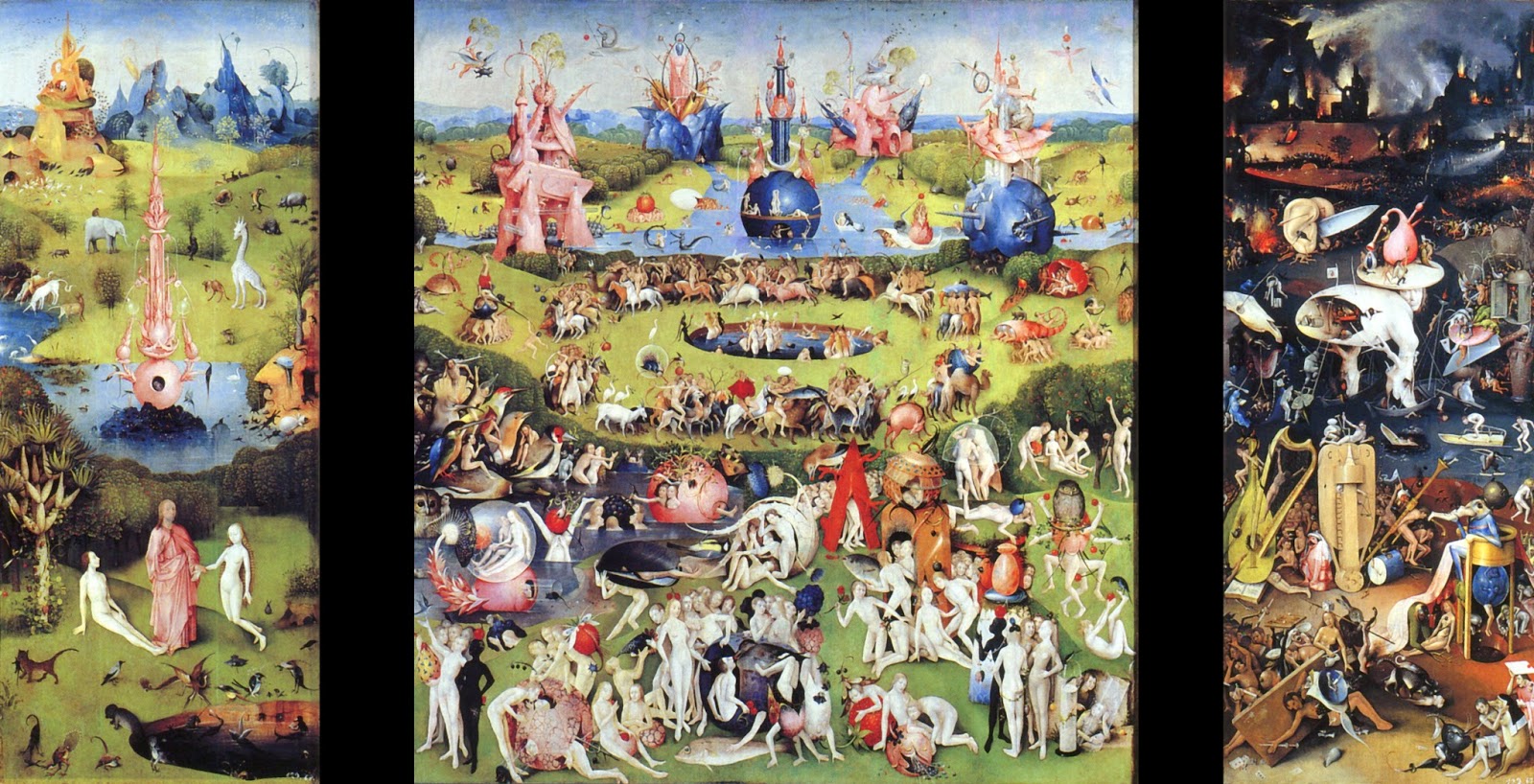

Stories almost never unfold in my head like films when I read, but I do sometimes 'see' static images - paintings, photographs - often specific styles or artistic currents. Sometimes it's the other way around: I'm reminded of a book when I look at a work of art. The other day I went to Madrid for the first time, and I saw in the huge and wonderful Prado museum this well-known triptych by Bosch:

|

| Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490?) |

|

Immediately I was reminded - of course in part because I'd just read it - of

J.K. Rowling Robert Galbraith's

The Silkworm, with its grotesque gallery of monstrous protagonists and torture scenes:

|

| charming |

But also, one little detail called back to my mind a similarly gripping summer read from years ago I'd almost entirely forgotten, Michael Connelly's

A Darkness More Than Night... A Harry Bosch adventure, not coincidentally:

|

| it's a story full of Boschian owls, that's all I can remember... |

Now Galbraith and Connelly are linked in my mind as inextricably as Rundell and Caillebotte.

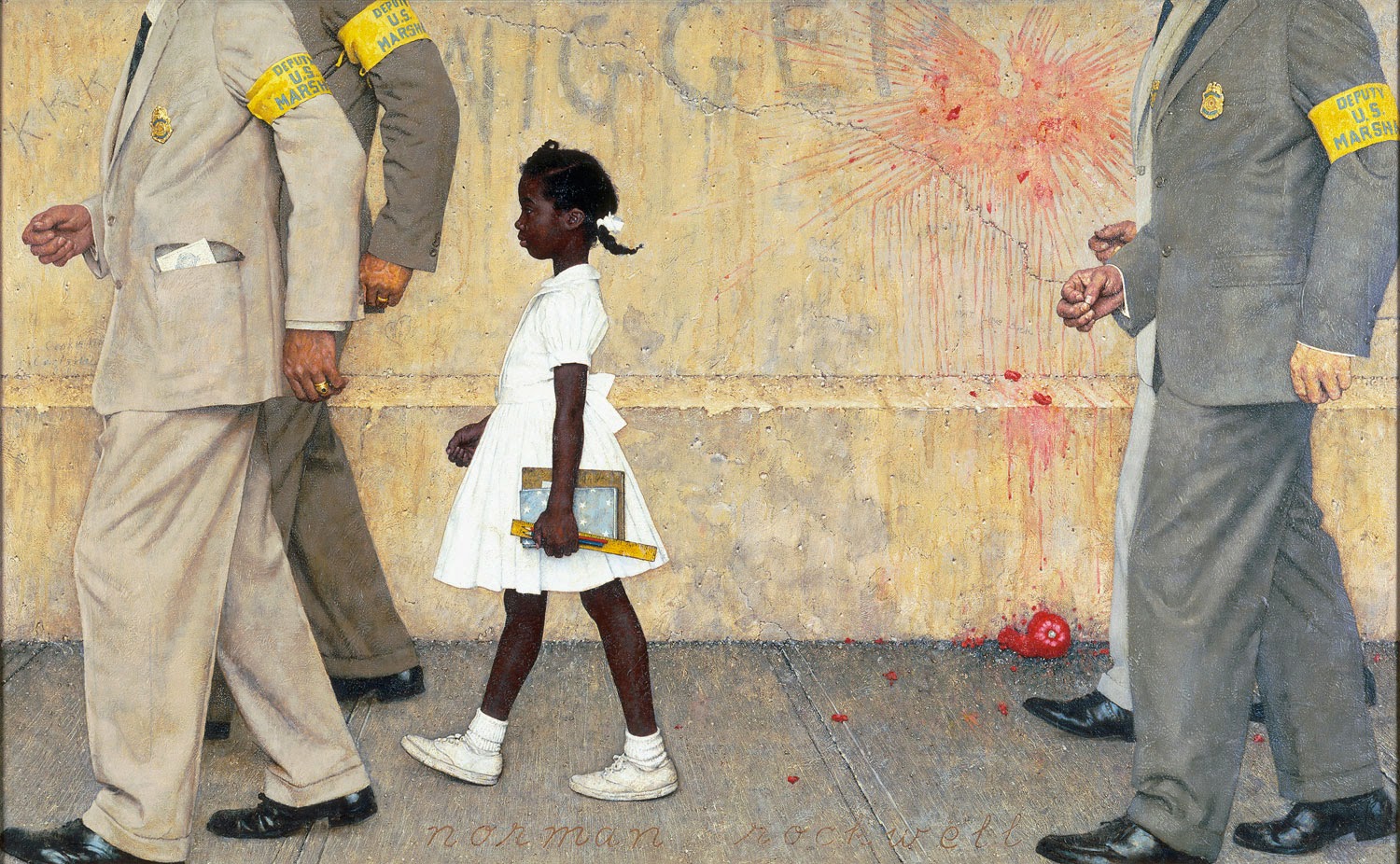

Generally, it happens with very famous rather than obscure works of art, perhaps because those tend to stick in one's head more. In children's literature, here are other associations, personal and therefore not always logical, though some are much more obvious than others:

|

| Lois Lowry's The Giver and the 1956 French film The Red Balloon |

|

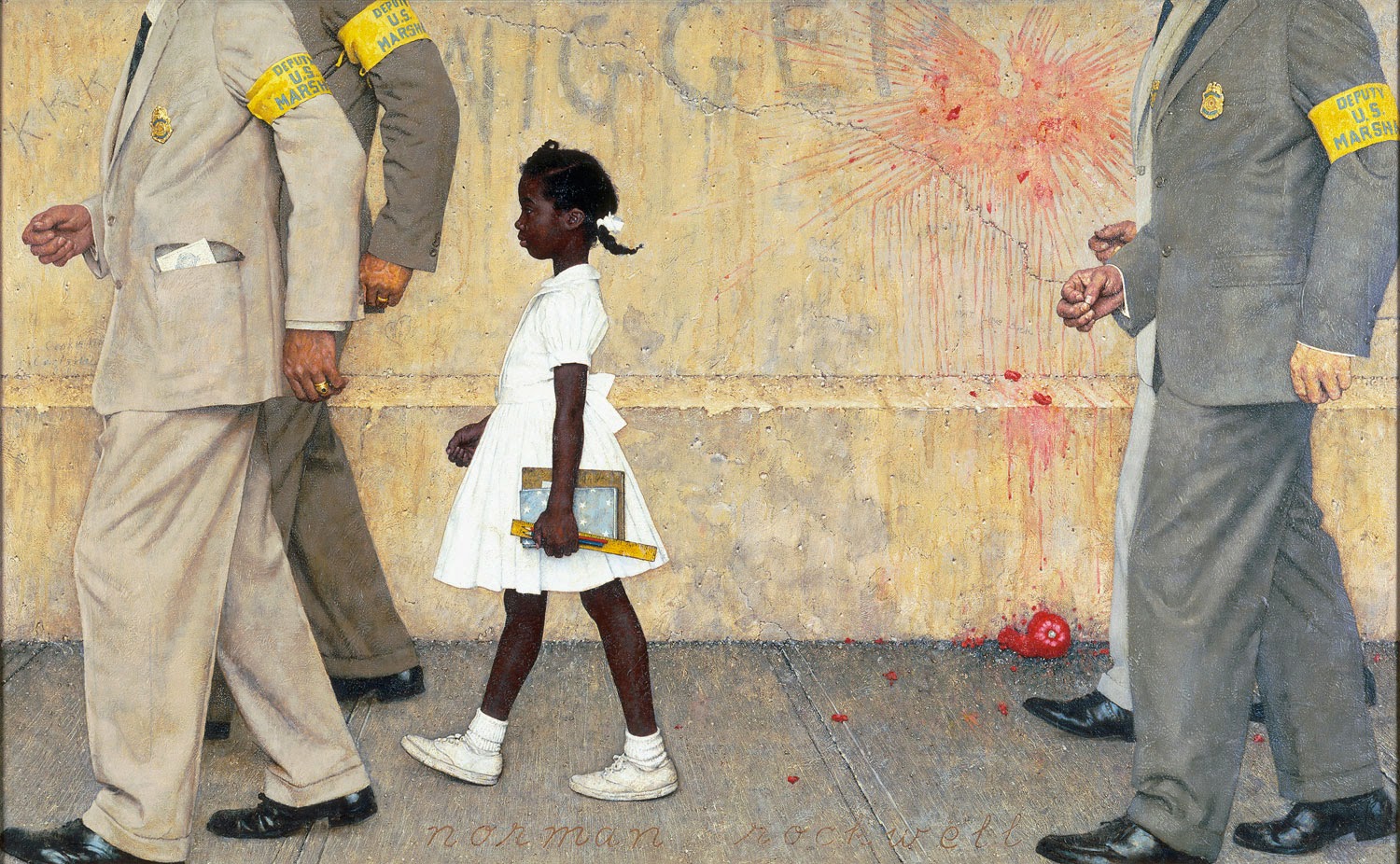

| Malorie Blackman's Noughts and Crosses and Norman Rockwell's 'The Problem We All Live With' (1964) |

Sally Gardner's

Maggot Moon is

Anselm Kiefer all the way. Anne Fine's

The Tulip Touch is this Edward Hopper...:

|

| yep, it's the Bates Motel, too... not a coincidence, I'm sure. |

I didn't like Neil Gaiman's

Coraline very much (sorry), but it was Louise Bourgeois's 'Maman' spiders:

Some authors make explicit reference to paintings, films or other visual art forms, like Marcus Sedgwick in

Midwinterblood. I love that - I love looking up the works of art mentioned in books, especially when I have no clue what they are and it throws a completely new light on the text. Some painters, some paintings and some movements seem to crystallise writers' attention. Da Vinci, of course, but also the Surrealists in general, it seems.

Similarly, when I write, I never really picture my characters in my head, but there's always a

lot of colours, and many static images, like paintings or stills from films or photographs. Fun adventure stories, whether I write them or read them, look quite like Sonia Delaunay's circles and spirals:

|

| Pippi Longstocking! |

Is it a kind of synaesthesia? Not sure, it's not automatic - it only happens with some books, and some paintings or works of art. It also depends hugely on what I've just read or seen, and in which contexts. Does that happen to you too? With which texts and which images?

_____________________________________

Clementine Beauvais writes children's books in French and English. The former are of all kinds and shapes, and the latter humour/adventure series - the

Sesame Seade mysteries with Hodder, the

Holy-Moly Holiday series with Bloomsbury. She blogs

here about children's literature and academia and is on Twitter @

blueclementine.

After the let’s-call-it fruitful debate a few months ago on this blog on the value of reading, I was left uneasy. I felt that the question I was truly interested in hadn’t been addressed; instead, the discussion revolved around ‘trash’ and ‘quality’ literature, which wasn’t what I felt to be central to my post.

But I fully understand why. My original post was unnecessarily vociferous and talked about ‘trash’ without definition. I knew very well that it would be a controversial post, but I wrote it too fast and I should have anticipated that this particular aspect would dominate the discussion.

What I was really interested in was the following question: ‘Who benefits most from the notion that any reading is preferable to no reading (or to encounters with other media such as films and video games) in childhood?’

My original blog post failed in part because I was not assertive enough in expressing why there may be an issue with the valorisation of (‘just any’) reading in childhood. I tentatively said things like ‘There are problematic ideological and economic reasons why…’, but didn’t spell them out. I would like to go back to this point because I do think it’s important to have a discussion about it.

Of course, I see reading as essential – and not just because verbal literacy is an important skill. Like all of us on this blog, I do believe that there is something about reading that sets it apart from other types of artistic or fictional encounters, and I love nothing more than seeing children who enjoy reading.

However, I think we have to admit that that somethingis very hard to pin down, and I am unconvinced by the unspoken hierarchy which puts reading ‘above’ film-watching, video-game-playing etc. in the minds of adults who care about and look after children.

(Therefore I completely agree with all the commenters who said that there should be no hierarchy between ‘classic’ novels and comics, for instance. I said this in a comment that got buried somewhere: I am NOT a 'genre' or 'media snob': I do not classify 'low' and 'high' quality literature in terms of genres or media. On the contrary; I think such distinctions can only exist within genres and media. This is between brackets because I don’t wish to get into another conversation about ‘trash’ and ‘quality’, but go ahead if you really want to…)

I’m unconvinced by this hierarchy, but moreover I am worried about who and what it serves. Of course, it uncontroversially serves children. Having motivated and passionate mediators, teachers, librarians, parents who value reading makes children from all backgrounds more likely to encounter books and to enjoy reading.

However, the undebated claim that any reading is good is also highly profitable to the publishing industry as a whole, indiscriminately. And here I'm uncomfortable. As authors, we don’t want to criticise the publishing industry; we want to support it. Publishing is in a state of unprecedented crisis, so we don’t want to make distinctions as to which parts of the industry to support and which parts to criticise, especially on such elusive grounds as ‘quality’.

Furthermore, authors are under pressure (implicit or explicit) not to express negative opinions they may have about the publishing industry. Mid-list authors, especially, can’t afford to talk about requests they get to make books more commercial, more gendered or less political. The problem doesn’t come from individual editors of course; very often they are distraught to be making such requests. They are themselves under pressure from other departments.

Regardless; in the Anglo-Saxon market, children’s publishers profit to a very large extent from the consensus that any readingis better than no reading when it comes to children. We should talk about this fact much more than we currently do, because it is problematic. The publishing industry has a very strong financial incentive in maintaining this consensus – and currently, I think that we (authors, mediators, teachers, librarians= 'child people') are maintaining it for them, for free.

When we say that ‘it’s good’ that children are reading, whateverthey may be reading, we are not just supporting ‘reading for pleasure’ (though I accept that we are in part). The sincere desire to be on the side of children is not met by an equally sincere wish on the part of the publishing industry, too many aspects of which are utterly unburdened by such considerations as artistic worth, child development or the value and pleasures of reading. And yes, I know, #NotAllPublishers.

Like several other commenters, I think the dichotomy between ‘reading for pleasure’ and ‘serious’ or ‘quality’ reading is hugely problematic. This dichotomy happens to profit, very conveniently, contemporary children’s publishing in its most undesirable aspects.

By ‘most undesirable aspects’ I mean extreme commercialism, market imperatives superseding or driving editorial work, reliance on formulae and ‘what sells to TV or cinema’, etc. And often, this leads to the production of books which are ideologically problematic (resting on lazy sexist, racist, classist, etc., clichés).

There is always the argument, of course, that those profit-driven aspects of the publishing industry serve to fund the more niche, quality books. This argument may be valid in part, but it’s too neat a defence to convince me fully.

I’m not naïve – I know very well that ‘publishing isn’t a charity’ (that’s something we hear a lot as writers - another mantra we gradually internalise.) I don’t think there is an easy solution to these problems. Other countries do things differently, privileging quality and accepting very niche books, but writers earn much less money than we do here (yes, it’s possible…) and there’s virtually no way of scraping a living out of writing.

I do believe that a quiet way of making a small difference could be to stop condoning the indiscriminate statement that any reading is a good thing (which doesn’t mean ripping books out of children’s hands – just saying this in case someone is tempted to pull the ‘censorship alert’ cord).

A not-so-quiet way is to have this kind of debate, politely but firmly, on a public forum such as this one.

_____________________________________

Clementine Beauvais writes children's books in both French and English. She blogs here about children's literature and academia and is on Twitter @blueclementine.

I don't 'do' Snapchat, unlike my little sister (19 years old), but I love dreaming about the narrative possibilities it offers. A murder mystery, where the serial killer sends short Snapchat videos with clues every time s/he strikes...

|

| yeah, the logo looks more like a Casper story |

Anyway, I'll never write that story, but I do love literature that talks about new technology. In many ways, it's difficult to think of a contemporary social realistic story, especially for teenagers, which wouldn't include smartphones and apps - Facebook, Tumblr, 2048, Google Maps - as a solution to many of the traditional adventure plotlines (nope, sorry, you can't be

actually lost; nope, sorry, you can't

actually be bored waiting for your train; nope, sorry, you couldn't

not have known that she was in a relationship (and it's complicated)).

But I like it even more when stories integrate technology in a non-gimmicky way - as an essential part of the plot, as the plot. Many such stories are realistic: it's impossible to keep track of stories that revolve around mystery blog-writers, from rom-coms to dramas. Others are supernatural, but even a fantastical story like

iBoy by Kevin Brooks is based on very real features of contemporary smartphones.

New technology offers possibilities both for entirely new plots and for interesting spins on older plots. There's been a spate of YA novels recently that revolve around revenge porn - one of them, in France, is mine. Of course revenge porn existed before smartphones, but the order of magnitude is different now, and so are, therefore, narrative possibilities - especially regarding character development, and some central themes of YA literature, such as gossip or bullying.

In my latest YA novel,

Comme des images, there are snippets of Facebook conversations, YouTube comments, texts, emails - breaking up the narrative from time to time. Those are

other voices, seemingly external to the plot, but actually crucial to it - because

the existence of those hundreds of other voices is the very reason why the central event is so important: it isn't just there, it's also commented on, in the whole world. Of course, you need to get those voices right, because it can just fail to ring true. Being friends on Facebook with teenagers of that age - in my case, my sister and all her friends - can help. I'm not sure I'd dare do it in English, where I'm not as familiar with the language used by teenagers.

So does being very active on these platforms, or at least having an excellent understanding of them. I cringe when I read books in which it is clear that the author (either by themselves or pushed by an editor) has attempted to include some (generally gimmicky) references to apps, software, video games or device without knowing anything about it (

"'I sent you a Twitter yesterday!' she chuckled.").

Hybrid texts where 'normal' narrative is sporadically broken by other types of discourse - from mock-tweets to mock-Wikipedia articles - can be highly sophisticated. There is immense value in harnessing the narrative possibilities that technological innovations offer us, not to be trendy; in part so that we continue to map, as faithfully as possible, the changes that are occurring in teenagers' lives, and make guesses as to how they might influence their personalities, their reactions, their tastes, their values. But it has literary and artistic value, too.

Such uses are not - or shouldn't be - just a way of spicing up a dull, ordinary story: they can be the opportunity for intensely original, groundbreaking advances in storytelling, for YA literature and beyond.

The only imperative is to avoid at all costs 'giving a message', 'warning' teenagers 'against' the 'dangers' of 'technology'.

But frustratingly, in order to make them palatable to mediators, this pedagogical 'guarantee' is frequently used to qualify works which should instead be praised for being uncomfortable or unsettling, both ideologically and linguistically. Let's keep the unease, at all costs. Personally, in my double life - virtual, real, barely separated - saturated with a myriad different voices and worldviews, I have no patience for consensus and all the time in the world for controversy.

______________________________________________________________________

Clementine Beauvais writes books in both French and English. The former are of all kinds and shapes, and the latter a humour/adventure detective series, the

Sesame Seade mysteries. She blogs

here about children's literature and academia and is on Twitter @

blueclementine.

OK, who's up for some more controversy? Just kidding. This time, what I've got in mind shouldn't earn me so many death threats and marriage proposals; I want to talk about child-reading 'scopophilia', a term slightly nicer than voyeurism: the pleasure adults derive from looking at children reading.

|

| Henri Lebasque |

Visual art, in particular painting, is full of children reading, presumably in part because posing for hours is an incredibly boring thing to do for an eight-year-old so it's a good way of keeping them still. Look at the amazing number of paintings on

this Pinterest devoted to that theme.

But it's not just convenience,

it's also a fascination of sorts. There is, apparently, something profoundly romantic, profoundly moving, and also rather erotic, about the image of a child reading. This is by children's literature scholar Peter Hollindale:

One January afternoon many years ago I was window-gazing in the shopping streets of Cheltenham... In the window of an art shop I sawa picture of a boy, lying on his bed, reading. He was dressed in pyjama bottoms, spreadeagled over the bed in an attitude of rapt and intense involvement in his book.... "That", I thought, "is what I want to produce. If being an English teacher is about anything worthwhile, it's about that." (The Hidden Teacher, 2011 p.12)

I don't need to stress the transgressiveness of this description: the adult's delight in this very intimate scene (a child on a bed, lost in his fantasies, in "rapt" and "intense involvement" - onanistic to say the least...) and his desire to elicit such

jouissance in the future, too... Of course, Hollindale is aware of all these innuendos.

There is something in visions of children reading that creates longing and a kind of pleasurable loss in the adult viewer. And art and literature frequently attempt to capture that something.

It's all the more interesting when it happens in a children's book.

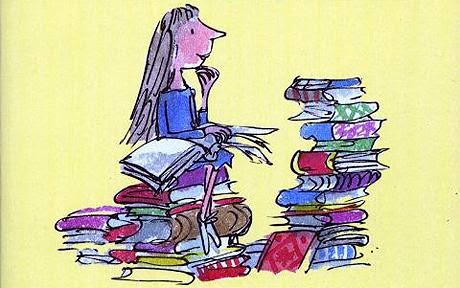

Matilda is the perfect example.

Over the next few afternoons Mrs Phelps could hardly take her eyes from the small girl sitting for hour after hour in the big armchair at the far end of the room with a book on her lap. … And a strange sight it was, this tiny dark-haired person sitting there with her feet nowhere near touching the floor, totally absorbed in the wonderful adventures of Pip and old Miss Havisham. (Matilda, 1988 p.19)

There's a form of religious adoration in the way adults look at Matilda while she's reading. Mrs Phelps and Miss Honey are described as 'stunned', 'astounded', 'quivery', 'filled with wonder and excitement.'

What's the position of the child reader when they read this passage? Well, it's quite weird. They're aligned with an adult viewpoint on another child reading, and enticed to take pleasure in it too.

But by virtue of being themselves child readers, they're also enticed to see themselves as a pleasurable sight to adults, an object of quasi-religious desire and fervour. Why are visions of children reading so inspiring for visual artists and authors?

It's not just that they like children who are 'absorbed' in a story: the vision of a child 'absorbed' in a film or video game does not have the same effect. There's something about reading that makes adults particularly nostalgic, and particularly emotional.

Part of it is simply nostalgic remembrance of our own days of reading as a child, if we were also big readers. Part of it is also linked to the ideologically problematic celebration of reading over other activities (

cf previous controversy ok I'll shut up).

But part of it may be also that we can't have access to what exactly the child has in mind when s/he reads - we may know the book, but what we picture of it in our minds cannot be the same as what s/he is currently picturing. There is mystery there, something secret, and like all secrets of childhood, we are quite fascinated by it.

Maybe we like to see children reading books because

there's just enough mystery (what

exactly are they

seeing there?)

and just enough control (it's a book; s/he's safe). This Goldilocks zone is perfectly titillating.

|

is that child reading

or thinking of something else? |

In Claudine's House, French writer Colette writes about how disturbing she finds it when her daughter, Bel-Gazou, is sewing. It is more dangerous, scarier than when she reads, Colette says. When Bel-Gazou reads, "she comes back, looking lost, flushed, from the island with the jewellery-filled chest... She is full of a tried and tested, traditional poison, the effects of which are well-known."

But when Bel-Gazou sews, "Let's write the word that scares me: she thinks…" "What are you thinking about, Bel-Gazou?" "Nothing, Mummy."..."Mummy?""Darling?""Is it only when you're married that a man can put his arm around a lady?""Yes... No... It depends... Why are you asking me this?""No reason, Mummy." With no trace in her daughter's hands of a book that could have triggered these questions, the mother is faced with Bel-Gazou's thoughts in freefall, and a terrifying question - where

are they coming from?

_____________________________________

Clementine Beauvais writes children's books in both French and English. The former are of all kinds and shapes for all ages, and the latter a humour/adventure detective series, the

Sesame Seade mysteries, with Hodder. She blogs

here about children's literature and academia and is on Twitter @

blueclementine.

Is it better to read 'anything' rather than 'nothing'?

Like most people interested in children's literature, and like many authors, I like asking booksellers, librarians, teachers and parents what children and teenagers are currently reading a lot of. And like many children's literature academics, I don't conceal my disappointment and my judgement when they tell me that a lot of children are reading what I consider, subjectively of course, but still with (I hope) some good reasons, to be trash; bad literature; literature that is facile, bland, formulaic; literature that relies on easy responses from young readers; literature that doesn't count on the intelligence of its readers to be understood.

In response, people often say, 'Sure, I agree with you - these books are awful. But at least they're reading.'

'At least'. At least they're reading. This is such a minimal kind of success that it doesn't, in my view, actually qualify as any kind of success. At least they're reading! hallelujah... When do you ever hear people who care about children say: 'Oh, they love fries and cheeseburgers. Sure, McDonalds food is awful, but at least they're eating.' ?

It's like 'reading' is a monolithic 'thing' that one 'should' do, that it is always good to do. It's like there's no other alternative. Reading instead of doing what?

If the other option is going around throwing puppies off cliffs, sure, I'd rather they be reading. If the alternative is watching reality TV, would I still prefer them to be reading? To be entirely honest, I wouldn't really care either way. Undemanding, unsophisticated TV is equivalent to undemanding, unsophisticated books in my mind. If the alternative is watching the latest Pixar film, I'd much rather they watched that. But comparing activities is, on the whole, a fairly fruitless debate.

The myth that all reading is good is associated to the myth of trashy reading as 'gateway' to better reading: 'But then they'll read more sophisticated books!'. I doubt it.

Reading sophisticated, demanding books is not the 'next step' on the same literary ladder as trashy, unsophisticated fiction. It's a different kind of reading altogether. It follows the reading of sophisticated, demanding children's fiction, not the reading of undemanding, unsophisticated children's fiction. It's a type of reading which requires a specific, rather ascetic mindset, a mindset which cannot be a comfortable step away from trashy literature. A mindset which, I would argue, is in fact directly at odds with the one cultivated by trashy literature.

However, it could be a sidestep, or a parallel step, to the watching of demanding, sophisticated films, or the playing of demanding, sophisticated video games.

To me, there is no value, and I do mean zero value, in reading books which (most adults agree) are of low quality - lazy, unoriginal, facile and immediately appealing. It is dishonest, I think, to keep asserting that it is a good thing in itself.

Oh, I'm aware, by the way, that all of the above makes me sound like a horrible snob. I'm also aware that it is a frequently-debated issue, and that people have very strong feelings about it.

It's important that we keep having this discussion. There are problematic ideological and economic reasons why so many well-meaning adults (who would never be content to see children swallow down huge quantities of junk food) just go 'Oh well!' and smile when they see them gulping down the literary equivalent of junk food.

The relativistic myth that obviously, 'all reading is good', followed by the idea that obviously, 'trashy reading will lead to better reading', is hugely convenient, in both financial and political terms, to a lot of people.

So let's keep talking about it, because in these benevolent sentences there are transparent values, much too 'obvious' to be benign.

_____________________________________

Clementine Beauvais writes children's books in both French and English. The former are of all kinds and shapes, and the latter, a humour/adventure detective series, the Sesame Seade mysteries. She blogs here about children's literature and academia and is on Twitter @blueclementine.

My new research project for my academic work is on precocious children in literature and culture. I was trying to explain this in wobbly Spanish to my friend in Madrid by saying that I was studying 'el niño precocido', which made her burst out laughing - turns out it means the 'precooked child'.

It's a shame I'm not actually doing that; as far as I'm aware, it's a very undertheorised motif.

|

| Maurice Sendak, In the Night Kitchen |

Anyway, the term 'precooked' keeps popping back into my head as I read. Throughout the 20th century, there's been a conceptual battle around the question of child precocity in child psychology and the sociology of education. 'Precocious' children are now widely considered, as the etymology suggests, to be '

praecox',

'ripe before their age', mostly thanks to an alignment of good circumstances: supportive family and school environments, task commitment, and above all social valuation of whichever type of 'intelligence' the child manages to develop ahead of peers.

But the literature, though it does acknowledge parental involvement in so-called child 'precocity',

can be vociferous against parents. Parents are often described as 'pushing' their child, 'too early', with no regard for 'normal development'. In other words,

they're indeed 'precooking' their child in the hope that it will have the equivalent effect as their 'ripening early'. And everyone knows that no amount of apple compote will make up for their being unripe.

Even scientifically rigorous articles get into very harsh denunciations of parents who try to 'create' 'precocious' children.

Some scholars make the striking claim that exceptional children ahead of their peers who have been 'pushed' by their parents don't 'deserve' to be called precocious. Since the notion is essentially fallacious, its definition fluctuates anyway, but the hostility against the 'pushy parent' is interestingly intense.

Roald Dahl's

Matilda famously begins with a critique of such parents:

It’s a funny thing about mothers and fathers. Even when their own child is the most disgusting little blister you could ever imagine, they still think that he or she is wonderful.

Some parents go further. They become so blinded by adoration they manage to convince themselves their child has qualities of genius.

Children's books and films are indeed generally quite severe against parents who 'push' their children to 'overachieve', and don't grant them the same status as children presented as 'naturally gifted'.There's a clear moral split between the precooked and the precocious, even if in effect they achieve the same results.  |

| The bad precocious child |

Dahl is at the forefront - think of the punishments endured by the 'precooked' children of pushy parents in

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

The myth of child precocity is paradoxical. It's torn between conflicting adult desires that such children should be, on the one hand,

entirely unexplainable (a conservative, mystical view of precocity) and on the other hand,

possible to create (from a more liberal democratic perspective).

So

we don't like the idea that some children should be born with more 'gifts' than others: that hurts our egalitarianism. But at the same time,

we definitely don't like to see how they're made, how they're cooked, specifically by their parents. It feels like we're just being tricked ('it's not real precocity!'). The ambiguity of this discourse is reflected in scientific articles about child precocity or 'giftedness', and often in children's books and films.

|

| TMI. |

At heart,

we want to believe in the possibility of a 'miraculous' child whose intelligence and creativity has no rational explanation. We also think that pushy parents are only pushy out of pure narcissism. And also, yes, we're jealous: who are these parents who are so 'gifted' at this parenting thing? (Judging from my Facebook feed, it's a ferocious competition out there).

We prefer to think that they will suffer a sad fate, and their children too. They will be punished for precooking children when they aren't ripe enough. HA!

Children's literature from Jacqueline Wilson to J.K. Rowling often indulges in such dreams, with

cautionary tales that such 'fake precocious children' will never 'achieve their potential' and instead end up depressed and lonely - or, for the more positive tales, rebel before they're completely rotten.

|

| The good precocious child |

How hypocritical we writers can be... We know that we depend on an army of pushy middle-class parents to get their kids to read our books; increasingly so with the rumoured decline of the book. We deify precocious, 'gifted', 'genius' children in our texts. And we desperately want to have an impact on children, too.

And yet

the ideal precocious child is uncooked, free from additives, a mystery to all. It is a child who laughs at the efforts of well-meaning adults to influence her.

That ideal precocious child lands in our writerly nets.

And then we can give it our books.

Children's literature is absolutely OK with 'real' precocious child characters reading our books. We just

love being in charge of the cooking.

_____________________________________

Clementine Beauvais,

hypocrite auteur of several books featuring precocious children, writes in both French and English. The former are of all kinds and shapes, and the latter a humour/adventure detective series, the

Sesame Seade mysteries (Hodder). She blogs

here about children's literature and academia and is on Twitter @

blueclementine.