new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Tension, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 53

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Tension in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

I recently saw an advanced screening of the film The Spectacular Now. This honest and moving film is based on Tim Tharp’s YA novel (which also happens to be a National Book Award Finalist). The story follows Sutter Keely (Miles Teller), a high school senior determined to live in the present and forget the future, as he stumbles from one good time to the next. With a flask in one hand and his happy-go lucky attitude in the other, Sutter gets involved with the sweet and shy, Aimee (Shailene Woodley). But disaster is coming … because who can live in the present moment forever?

I recently saw an advanced screening of the film The Spectacular Now. This honest and moving film is based on Tim Tharp’s YA novel (which also happens to be a National Book Award Finalist). The story follows Sutter Keely (Miles Teller), a high school senior determined to live in the present and forget the future, as he stumbles from one good time to the next. With a flask in one hand and his happy-go lucky attitude in the other, Sutter gets involved with the sweet and shy, Aimee (Shailene Woodley). But disaster is coming … because who can live in the present moment forever?

I’m going to try really hard not to spoil this movie (because you really should go see it). But what I want to talk about is the film’s uncanny ability to build tension based on the audience’s expectation of impending disaster… and then, never fulfilling that expectation.

Let me give you an example: If I show you a character who’s an alcoholic and then I hand that character the keys to a fancy new car, what do you expect to see happen in the next scene?

A car crash of course.

This is a classic example of reader interaction. Readers love to guess what is going to happen next. It builds tension. It gets the reader involved as a participant in the story. It’s fun to wonder what will come next! But a great story doesn’t usually fulfill that expectation. It exceeds it. This is where crazy plot twists come from. The reader thinks a plot will go one way, and then — BAM! — it zags in a whole other direction. What a thrill!

Only, The Spectacular Now doesn’t really do that either.

It doesn’t try to up the ante with a new twist or an even bigger payoff. In fact, the film doesn’t like to payoff the viewer’s expectation at all. Sure, this sounds absolutely frustrating, but in actuality it’s surprisingly fulfilling and honest. Because how often does disaster really strike in our lives? Yes, we are always afraid of it (and that’s the exact expectation the story is playing on), but I bet most of us would agree that our lives are never as intense or dramatic as a film or novel. It’s the fear of what’s coming that scares us. And that turns out to be the primary tension of the movie. Disaster is hanging out there, somewhere in the future, but the future is what the protagonist is trying so hard to avoid. It’s brilliant, and at the same time, there’s something insanely dramatic and fascinating in Sutter’s ability to avoid it!

I wanted to bring this up because I feel like stories far too often choose the dramatic disaster. This is particularly hard to avoid when films overwhelm us with explosions and fights to the death. But I think there’s room to make writing choices without the spectacle. Choices that can be just as powerful. Choices that might actually be more honest and fulfilling because they don’t “go there.” I feel like so much of our lives (our real lives, not fictional character lives) are built on the tension of unfulfilled promises and that space between living in the now and looking toward the future. That feeling – that’s what The Spectacular Now so beautifully captures. And frankly, its one of the best films I’ve seen in a long time.

Go see it.

I recently saw an advanced screening of the film The Spectacular Now. This honest and moving film is based on Tim Tharp’s YA novel (which also happens to be a National Book Award Finalist). The story follows Sutter Keely (Miles Teller), a high school senior determined to live in the present and forget the future, as he stumbles from one good time to the next. With a flask in one hand and his happy-go lucky attitude in the other, Sutter gets involved with the sweet and shy, Aimee (Shailene Woodley). But disaster is coming … because who can live in the present moment forever?

I recently saw an advanced screening of the film The Spectacular Now. This honest and moving film is based on Tim Tharp’s YA novel (which also happens to be a National Book Award Finalist). The story follows Sutter Keely (Miles Teller), a high school senior determined to live in the present and forget the future, as he stumbles from one good time to the next. With a flask in one hand and his happy-go lucky attitude in the other, Sutter gets involved with the sweet and shy, Aimee (Shailene Woodley). But disaster is coming … because who can live in the present moment forever?

I’m going to try really hard not to spoil this movie (because you really should go see it). But what I want to talk about is the film’s uncanny ability to build tension based on the audience’s expectation of impending disaster… and then, never fulfilling that expectation.

Let me give you an example: If I show you a character who’s an alcoholic and then I hand that character the keys to a fancy new car, what do you expect to see happen in the next scene?

A car crash of course.

This is a classic example of reader interaction. Readers love to guess what is going to happen next. It builds tension. It gets the reader involved as a participant in the story. It’s fun to wonder what will come next! But a great story doesn’t usually fulfill that expectation. It exceeds it. This is where crazy plot twists come from. The reader thinks a plot will go one way, and then — BAM! — it zags in a whole other direction. What a thrill!

Only, The Spectacular Now doesn’t really do that either.

It doesn’t try to up the ante with a new twist or an even bigger payoff. In fact, the film doesn’t like to payoff the viewer’s expectation at all. Sure, this sounds absolutely frustrating, but in actuality it’s surprisingly fulfilling and honest. Because how often does disaster really strike in our lives? Yes, we are always afraid of it (and that’s the exact expectation the story is playing on), but I bet most of us would agree that our lives are never as intense or dramatic as a film or novel. It’s the fear of what’s coming that scares us. And that turns out to be the primary tension of the movie. Disaster is hanging out there, somewhere in the future, but the future is what the protagonist is trying so hard to avoid. It’s brilliant, and at the same time, there’s something insanely dramatic and fascinating in Sutter’s ability to avoid it!

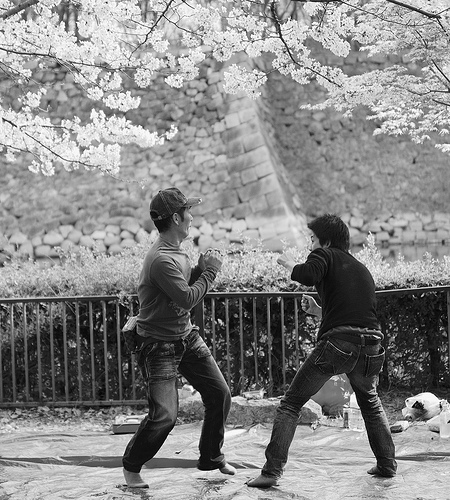

I wanted to bring this up because I feel like stories far too often choose the dramatic disaster. This is particularly hard to avoid when films overwhelm us with explosions and fights to the death. But I think there’s room to make writing choices without the spectacle. Choices that can be just as powerful. Choices that might actually be more honest and fulfilling because they don’t “go there.” I feel like so much of our lives (our real lives, not fictional character lives) are built on the tension of unfulfilled promises and that space between living in the now and looking toward the future. That feeling – that’s what The Spectacular Now so beautifully captures. And frankly, its one of the best films I’ve seen in a long time.

Go see it.

Your characters enter a scene. Something happens, preferably conflict. Now, stop and ask yourself, "What primed the pump?"

Hopefully one conflict scene leads to another conflict scene, but what if you are moving from one POV character to another or a great deal of time has elapsed in between scenes?

After you write a scene, take another look at it and consider what primed the pump. No one enters a situation as a blank canvas.

1) What was Dick doing or feeling immediately prior?

It may be obvious if Dick is moving between consecutive scenes. Whatever happened in Scene 3 primes Scene 4. A plot hole occurs when something happens in scene 3 and is never addressed again. You don’t have to waste a lot of page time explaining what happened in between if it isn’t essential. However, if Dick was upset in Scene 3 and is perfectly calm when we see him again in Scene 7, then something happened to diffuse his mood. You should probably reference it with a line of dialogue or interiority during the opening transition paragraph of the new scene.

2) What is each character’s mindset as the scene progresses?

Every character entering a scene has thoughts and feelings. Are they having a good day or bad day? It affects their receptiveness. Whatever happened in prior scenes could have bearing on the current scene. Conflicting emotions and situations prime the conflict pump. If Jane is happy and Dick is angry, they could trade moods quickly.

3) Has your scene been properly set up?

Have you brought up an important point that you let lapse? Are the characters conflicted over something that makes no sense because you forgot to mention it in a previous scene? You may have cause and effect plot holes. If so, you have some revision to do. Beta readers or critique partners can be invaluable in catching these. My groups calls it the "read the book in my head, not the one on paper" syndrome.

4) Where does your scene take place? Why?

Settings are often bland and add nothing. You add value when you set the scene in a place that heightens tension. It has to be logical and organic. Don’t do it because “the script called for it.” If your couple is having an argument at home in the kitchen, it is realistic but is it interesting? Is the kitchen the best place for the argument? Can you make the setting more awkward for them? Say, a PTA meeting or on a crowded bus ride home?

5) Who is present?

You can have intense dialogue between two characters while they are alone. You add tension when they are striving to not be overheard or are wearing forced smiles at a formal function surrounded by family or coworkers. When two people are focused on each other, the crowd has a way of disappearing. They sometimes forget that other ears are listening. Being overheard can create future conflict. Having to behave decorously can force them to resume the conversation at another time, thus priming the pump for a future scene.

Consider not only the timeline of your story but how the timeline of the conflicts prime the pump. What happens immediately before can be as important as what happens during and immediately after.

By:

Roberta Baird,

on 5/25/2013

Blog:

A Mouse in the House

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

mission impossible,

Texas,

houston,

tension,

www.robertabaird.com,

cat on a wire,

children's illustration,

digital art,

roberta baird,

cat,

artwork,

a mouse in the house,

illustration,

Illustration Friday,

animals,

IF,

Add a tag

Proof that cats do indeed watch television.

After his people watched the entire “Mission Impossible” weekend marathon, Miles, wanting to get “in touch” with the wild feline within and sneak up on his food, took the matter into his own hands.

If only he hadn’t miscalculated the height from the kitchen light to the floor, he’d be in kibble heaven right now!

One of the big rules we always hear about writing is that there must be conflict! Without conflict you have no tension, no stakes, and the story doesn’t go anywhere. Some say “without conflict you have no story” at all! Therefore we should always be on the look-out for the conflict in a scene and use it to make our stories more intense, emotional, and keep the boring-police away!

But, I have an admission. I’ve always had a problem with the idea that story revolves around conflict. I get nervous about how it limits what our stories can be about.

Don’t misread that comment. Conflict can be an important and useful storytelling tool, and there’s nothing wrong with using it. But… do we sometimes create conflict simply because we think we are supposed to? Are our lives defined by our conflicts? Is it all Man vs. Man, Man vs. Environment, Man vs. God, Good vs. Evil? Is it always about desire and obstacles and the conflicts that stand in our character’s way?

Is there not room for more?

This emphasis on conflict has always made me think of the fabulous quote in Diane Lefer’s essay, Breaking the Rules of Story Structure, where she says:

“The traditional story revolves around conflict – a requirement Ursula K. Le Guin disparages as the ‘gladatorial view of fiction.’ When we’re taught to focus our stories on a central struggle, we seem to choose by default to base all our plots on the clash of opposing forces. We limit our vision to a single aspect of existence and overlook much of the richness and complexity of our lives, just the stuff that makes a work of fiction memorable” (63).

Janet Burroway adds to this discussion noting that “seeing the world in terms of conflict and crisis, of enemies and warring factions, not only constricts the possibilities of literature… [it] also promulgates an aggressive and antagonistic view of our own lives” (Writing Fiction, 255).

These quotes have always resonated with me. I find I’m not an action-and-conflict writer. But at the same time, I didn’t have any other guidepost to lead me. So, if it’s possible for stories to revolve around something other than conflict, what would that “something else” be?

Connection.

In Writing Fiction, Burroway goes on to discuss a narrative engine built on the human need for connection, rather than the clash of opposing forces. She says:

“A narrative is also driven by a pattern of connection and disconnection between characters that is the main source of its emotional effect. Over the course of a story, and within the smaller scale of a scene, characters make and break emotional bonds of trust, love, understanding, or compassion with one another. A connection may be as obvious as a kiss or as subtle as a glimpse; a connection may be broken with an action as obvious as a slap or as subtle as an arched eyebrow” (255).

This is an idea I can get behind!

A pattern of connection and disconnection is a narrative guideline that feels rooted in truth, human desire, and hope. It’s a guideline that – if you need it to – can lead to conflict, should that be where you want your story to go. For me, the need for connection, and the movement between connecting and disconnecting, exists in a deeper space than conflict alone. Good vs. Evil sits on the surface. Connection and disconnection is the pulse beneath the skin that motivates our characters. Can good or evil exist without it? This question excites me! The possibility of small actions energizing a story excites me!

I believe in the little moments.

I believe in the impact of an arched eyebrows and a subtle glimpse, may they have the power to grip our readers with as much intensity as a fight to the death.

One of the big rules we always hear about writing is that there must be conflict! Without conflict you have no tension, no stakes, and the story doesn’t go anywhere. Some say “without conflict you have no story” at all! Therefore we should always be on the look-out for the conflict in a scene and use it to make our stories more intense, emotional, and keep the boring-police away!

But, I have an admission. I’ve always had a problem with the idea that story revolves around conflict. I get nervous about how it limits what our stories can be about.

Don’t misread that comment. Conflict can be an important and useful storytelling tool, and there’s nothing wrong with using it. But… do we sometimes create conflict simply because we think we are supposed to? Are our lives defined by our conflicts? Is it all Man vs. Man, Man vs. Environment, Man vs. God, Good vs. Evil? Is it always about desire and obstacles and the conflicts that stand in our character’s way?

Is there not room for more?

This emphasis on conflict has always made me think of the fabulous quote in Diane Lefer’s essay, Breaking the Rules of Story Structure, where she says:

“The traditional story revolves around conflict – a requirement Ursula K. Le Guin disparages as the ‘gladatorial view of fiction.’ When we’re taught to focus our stories on a central struggle, we seem to choose by default to base all our plots on the clash of opposing forces. We limit our vision to a single aspect of existence and overlook much of the richness and complexity of our lives, just the stuff that makes a work of fiction memorable” (63).

Janet Burroway adds to this discussion noting that “seeing the world in terms of conflict and crisis, of enemies and warring factions, not only constricts the possibilities of literature… [it] also promulgates an aggressive and antagonistic view of our own lives” (Writing Fiction, 255).

These quotes have always resonated with me. I find I’m not an action-and-conflict writer. But at the same time, I didn’t have any other guidepost to lead me. So, if it’s possible for stories to revolve around something other than conflict, what would that “something else” be?

Connection.

In Writing Fiction, Burroway goes on to discuss a narrative engine built on the human need for connection, rather than the clash of opposing forces. She says:

“A narrative is also driven by a pattern of connection and disconnection between characters that is the main source of its emotional effect. Over the course of a story, and within the smaller scale of a scene, characters make and break emotional bonds of trust, love, understanding, or compassion with one another. A connection may be as obvious as a kiss or as subtle as a glimpse; a connection may be broken with an action as obvious as a slap or as subtle as an arched eyebrow” (255).

This is an idea I can get behind!

A pattern of connection and disconnection is a narrative guideline that feels rooted in truth, human desire, and hope. It’s a guideline that – if you need it to – can lead to conflict, should that be where you want your story to go. For me, the need for connection, and the movement between connecting and disconnecting, exists in a deeper space than conflict alone. Good vs. Evil sits on the surface. Connection and disconnection is the pulse beneath the skin that motivates our characters. Can good or evil exist without it? This question excites me! The possibility of small actions energizing a story excites me!

I believe in the little moments.

I believe in the impact of an arched eyebrows and a subtle glimpse, may they have the power to grip our readers with as much intensity as a fight to the death.

Here are some tips to put tension, even if only a little bit, on each page of your manuscript.

http://jodyhedlund.blogspot.ca/2012/12/ten-techniques-for-getting-tension-on.html

<!--[if gte mso 9]>

0

0

1

947

5401

wordswimmer

45

12

6336

14.0

<![endif]-->

<!--[if gte mso 9]>

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

<![endif]--><!--[if gte mso 9]>

When thriller author Donna Galanti contacted me about guest posting here at The Bookshelf Muse on building suspense, I was all over it! As a writer on the dark side of Middle Grade and Young Adult, suspense is as alluring to me as the scent of bacon in the pan. And suspense isn't only about Thrillers and Who-dun-its...every book and genre has it's own brand of suspense, meaning catching and keeping the reader's attention requires some serious skill. Donna has 8 great tips for building suspense...I hope you enjoy this post as much as I do!

Writing Suspense: Meet Them in the Middle and They Will Come

I’ve learned so much about suspense since writing my first book. One thing I’ve learned in fiction, and movies, is that surprise can be over-rated.

Surprise is the two-seconds of “Boo!”

Suspense is the ten-minutes of “Oh, No! Will she die or not?” We’ve all heard

go for suspense when you can–and for a reason.

It keeps the reader turning pages. This means the reader needs to know a few things (without giving it all away) so they can predict things, and feel smart. Readers love feeling smart. Don’t we all?

I’ve discovered that if we meet the reader in the middle and let them feel smart, that they will stick with you. But how can we, as writers, meet the reader in the middle to create suspense?

Tease them with only a few descriptive details

In

Harry Potter we all know what Hogwart’s Castle looks like, don’t we? But if you go through the book there are very few descriptions about it. It’s introduced only as a vast castle with lots of turrets and towers. When Harry enters it we’re teased with brief images of flaming torches and a magnificent staircase. That’s it. The reader must fill in the rest with imagination.

By giving the reader flashes of the setting here and there we involve the reader, take them along for the ride, and…build suspense.

Introduce questions early on

Not just one, but many. Drop them here and there. Don’t make it tidy. Make it mayhem with meaning. But make sure those drops do have meaning.

If a knife appears hanging on the wall in the beginning, the reader will question why its there and believe that the knife has importance down the road. (So make sure you show its reason…later.)

Make the reader ask: What happens next? In

Watchers by

Dean Koontz we witness a depressed man who goes off to a canyon to commit suicide. Will he go through with it? Then he meets a highly intelligent dog and fears for his life from an unknown stalker. Through the dog he meets a timid woman he is intrigued by.

Now we have more questions. Who is this dog? Who is this stalker? How are they connected? Who is this woman? Why is she so shy?

Provide readers with knowledge

New novelists can often be afraid of revealing their best stuff early on. I used to feel the same way. There are tons of pages to fill, after all. That fear can make a writer hoard their best stuff for a surprise–later. But the reader can get bored with waiting, and surprises are overestimated.

Hitchcock, the master of film suspense, used this to build his tension in his movies. He gave the audience information the characters knew and didn’t know, such as the bomb located under their desk.

Tick tock.Will the character die? Yikes! Maybe, if we’re given all the information we need to suspect death is looming. What makes this suspenseful? Because we spend ten minutes hoping beyond hope the character we love doesn’t die! In the movies or on the page.

Look at the big picture

Movies can provide great visuals for how writers can create suspense. Multiple setups can lead to one big suspense payoff. It’s the knowing what’s about to happen, and then it happens.

In

The Godfather, Michael Corleone plans to kill the two mob leaders he meets for dinner. We see the murder planning. The discussion of where to meet. The finding of the gun in the bathroom as a weapon. The wondering of whether Michael will or won’t do it. The knowing that his life will be forever changed if he does.

Creating suspense with a big picture buildup can also create surprise. Here is where surprise can work if everything that led up to the surprise is exposed in a new way.

The big moment at the end in

The Sixth Sense isn't just a surprise–it re-arranges everything we know about the events we've seen beforehand in a new way. Did you guess it coming or were you totally surprised?

Set the mood

Provide a suspense setting that creates feelings of heightened anxiety. Give the reader the portent of doom. The setting of a scene can make a large impact on its mood. Use sensory details to build on those feelings–a sudden wind, a stormy sky, a rising stench, a jarring noise.

Use world building to create suspense.Here’s an example of how I aimed for this in my suspense novel,

A Human Element:The sky darkened suddenly. She looked up. Black clouds, thick and angry rolled overhead. Her heart raced faster. The bad feeling screamed again inside her.

"Let's go inside for now." Laura tugged on her mother's sleeve. They would be safer in the house. She just knew it.

"But we can't let our chores go." Fanny's fingers flew across the peas. Slit. Pop. Slit. Pop. Wind whipped around the corner of the house. It knocked over Laura's basket.

Do you think something bad is coming?

Go slow

You’re saying whaaat? Yes. Slow down real time to show the full 360 degrees of the scene. In real life action happens fast. But it’s our job as writers to not show real life. That would be boring and over with in a flash. Show all the angles of the scene to build suspense. Use all the senses. Add complications.

I just read

Robert Goolrick’s,

A Reliable Wife. In it he moves achingly slow to build suspense. In the beginning scene a man waits at a train station. Nothing is happening. But so much is happening. And so much is to come.

His first paragraph tells us:

It was bitter cold, the air electric with all that had not happened yet. The world stood stock still, four o’clock dead on. Nothing moved anywhere, not a body, not a bird; for a split second there was only silence, there was only stillness. Figures stood frozen in the frozen land, men, women, and children.

Oooh, right? Look at his words. Bitter. Electric. Dead. Still. Frozen. Besides going slow he’s also setting the mood with his word choices. These are not soft words. We have a sense of doom. For eleven pages at the train station Goolrick goes slow to build suspense and tension all by focusing on one man’s thoughts and the people who flow around him.Think that’s going slow? The master of suspense,

Dean Koontz, builds suspense over

seventeen pages in

Whispers with an attempted rape scene.

And don’t forget to create characters to care about

This doesn't mean they shouldn’t be flawless. Giving them flaws makes them more appealingly human, but you won’t create suspense if nobody gives a hoot about your characters.

Suspense is emotional. It’s about revealing some, but not all.

And if the reader cares they’ll go out on that limb and meet you in the middle. Build it halfway to create suspense, and they will come.

Donna Galanti is the author of the paranormal suspense novel,

A Human Element, called “a riveting debut that had me reading till the wee hours of the night” by international bestselling author

M.J. Rose.She’s lived from England as a child, to Hawaii as a U.S. Navy photographer. Donna lives with her family in an old farmhouse in PA with lots of nooks, fireplaces, and stinkbugs but sadly no ghosts. Visit her at her

website, and on

Twitter!About

A Human Element:

One by one, Laura Armstrong's friends and adoptive family members are being murdered, and despite her special healing powers, there is nothing she can do to stop it. The killer haunts her dreams and leaves cryptic notes advising her to use her powers to save herself...because she's next.

Read a sampleAdd this book to my GoodreadsYour turn, Musers! What techniques do you use to build suspense? Is there an author you love because of their skill at drawing the reader in and keeping them guessing? Let me know in the comments!

ALSO, I hope you'll sneak over to the ever-awesome Shannon O'Donnell's

Book Dreaming where I'm chatting about

Staying Motivated. I promise you will LOVE some of the links I'm sharing at her blog!

The other day, my son discovered Maury Povich, and it wasn’t just any topic. This was “whose the baby’s daddy.” I decided to watch with my tween son and use the show to drive home a few cautionary points. What I didn’t expect was a lesson in building tension.

First, they would bring out the young woman. She would tell her story and swear up, down and sideways that the guy they were about to meet was the father and she was going to prove it. THE PROTAGONIST had a GOAL.

Then Povich would interview the “father” who would swear that there was no way the child was his. He became the ANTAGONIST.

This alone would just be a case of he said, she said. But the producers made sure we got RISING TENSION. One guy said the baby didn’t look like him. Another pointed out that she had pulled this before; he had proved the first baby wasn’t his. The ANTAGONIST has a GOAL that goes against the protagonist’s goal.

At last, Povich held the envelope with the DNA test in his hand – the TURNING POINT. Invariably the man in question was not the baby’s father. Why invariably? To keep the TENSION high, and, believe me, with the tears, screaming and name calling, there was plenty of tension.

As writers, you need to manage the tension in your stories as if you were a producer on Maury Povich.

Start with your PROTAGONIST. What is her GOAL? If you are going to use it to create tension, it has to be a big deal. What is at risk if she fails? She doesn’t have to look foolish on national television, but the bigger it is the more tension you will create.

There also has to be someone or something in her way. If you use an ANTAGONIST, vs. nature or time, your antagonist doesn’t have to be evil. His goal just has to be at odds with the goal of your protagonist.

Before the end of the story, you need to INCREASE THE TENSION. The reader could learn something about the protagonist that puts her goal in question. Or another character could surprisingly side with the antagonist. In some way, the protagonist must meet a REVERSAL.

This is where so many of us fall down on the job. We like our characters and don’t want to be the cause of their suffering. We make things too easy. We make things boring while Povich and his producers keep throwing more and more trouble into the mix.

Do this and, like Povich, you will keep your audience on the edge of their seat, shouting, cheering and maybe even booing. The one thing they won’t be doing is putting aside your writing to watch something on TV.

–SueBE

Author Sue Bradford Edwards blogs at One Writer's Journey.

I am THRILLED to feature

writing guru K.M. Weiland on the blog today to discuss

Outlining. As a reformed panser, I have seen my writing evolve by

embracing outlining techniques. And while I'm not a full outliner yet, it is a tool that helps me at certain stages during the writing process to form stronger story structure and character development.

Katie's book,

Outlining Your Novel: Map Your Way to Success guides writers with a

step-by-step approach to developing and writing a novel. One of the story mapping techniques is

Reverse Outlining, a creative approach to help writers build a strong, cohesive timeline in their novels.

Read on for an excerpt straight from the book!

Reverse Outlining

When you think of outlines, you generally think about organization, right? The whole point of outlining, versus the seat-of-the-pants method, is to give the writer a road map, a set of guidelines, a plan. An outline should be simple, streamlined, and linear. An outline should put things in order. So you’re probably going to think I’m crazy when I tell you

one of the most effective ways to make certain every scene matters is to outline backwards.During the outlining process, we have to create a

plausible series of events, a chain reaction that will cause each scene to domino into the one following. But linking scenes isn’t always easy to do if you don’t know what it’s supposed to be linking to. As any mystery writer can tell you, you can’t set the clues up perfectly until you know whodunit. Often, it’s easier and more productive to start with the last scene in a series and work your way

backwards.For example, in my outline of a historical story, I

knew one of my POV characters was going to be injured so badly he would be unable to communicate with another character for almost a month.

However, I didn’t yet know how or why he was injured. I could work my way toward this point in a logical, linear fashion, starting at the last known scene (a dinner party), and building one scene upon another, until I reached my next known point (the injury). But because my chain of events was based on what was already behind me (the dinner party), more than what was away off in the future (the injury), my attempts to bridge the two were less than cohesive.

Had I outlined these scenes in a linear fashion, squeezing in the injury might have become a gymnastic effort instead of a natural flowing of plot. Plus, the fact that I had no idea what was supposed to happen between the dinner party and the injury meant I was likely to invent random and inconsequential events to fill the space.

My solution?You got it:

work backwards.Starting at the end of the plot progression—the injury—I

began asking questions that would help me discover the plot development immediately preceding. How was the character hurt? Where was he hurt? Why did the bad guys choose to do this to him? Why was he only injured, instead of killed? How is he going to escape?

Once I knew these things, I knew how I needed to set up the scene, and once I knew how to set up the scene, I knew what to put in the previous slot in the outline. Eventually, I was able to work myself all the way back to the dinner party. Voilà!

I now had a complete sequence of events, all of w

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 10/24/2011

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

novel,

character,

plot,

NaNoWriMo,

first drafts,

setting,

tension,

how to write,

situation,

Add a tag

I am thinking about doing NaNoWriMo this year, joining with thousands of others in trying to write 50,000 words–a novel–during the month of November.

I am thinking about doing NaNoWriMo this year, joining with thousands of others in trying to write 50,000 words–a novel–during the month of November.

You can’t count any words written before November 1, but I know I can’t do this if I don’t work on a plot before the mad rush officially begins. So far, I only have a situation.

What’s the difference in a plot and a situation?

A situation is a single event, a strange combination of story elements. For example, there’s an annual contest called Stuck on a Truck. The idea is for selected people to put their hands on a truck and keep them there. The last one standing–and still stuck on that truck–will win the truck. It usually takes 100 hours for the last ones to drop out. That’s 4-5 days with no sleep.

It’s an interesting situation and one that I’d like to write about. But it’s not a plot.

Transform a Situation into a Plot

For the situation to become a plot, I need to add characters with real problems they must overcome. I am sifting through the ideas for characters, looking for flaws, quirks and a heart for readers to connect with. I also need to add a setting, ground the story in a particular historical period (contemporary, historical, fantasy, etc.), a particular geographical place. And finally, I need to be mean, cruel, despicably unfair to my characters; in other words, I need intense complications that force my characters to make decisions they don’t want to make. Tension on every page.

Fortunately, there are 29 plot templates I can follow when considering options.

Also of interest:

Need help with something else? Use the Search Box to look for more information. Or ask a question in the comments or send me an email at darcy at darcypattison dot com.

Are you doing the NaNoWriMo? Why is it right for you this year?

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 9/21/2011

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

conflict,

connections,

voice,

characters,

plot,

tension,

how to write,

verbs,

novel revision,

Add a tag

Random Acts of Publicity DISCOUNT:

$10 OFF The Book Trailer Manual.

Use discount code: RAP2011

http://booktrailermanual.com/manual

I am working on a novel revision for an editor and I expect to turn it in by Monday. But today, as I was reading through one last time to polish everything up–oh, my gosh!–there’s still so much work to do.

Last Minute Revisions

At this point, it’s not major structural changes or big plot changes. Instead, I am looking to tighten every scene and make as many connections as possible. And I am polishing language and voice.

At this point, it’s not major structural changes or big plot changes. Instead, I am looking to tighten every scene and make as many connections as possible. And I am polishing language and voice.

Here are some thing that I’m working on:

Connections. I noticed that K gave A something. Now, K is a minor character, and while I like K, the connection here was weak. Instead, I wondered how the story would work if C gave A that same thing. Much nicer! It brought back in a sub-plot/theme with C that I thought would never work into this part of the story.

Conflict and Tension. Yes, the mainstay of fiction is conflict and tension and you’d think I would have that right by now. Instead, I realized that I was relying on the external conflict and ignoring the internal conflict. What I needed was conflict to be within my main character, while at the same time, she is facing external problems. I had to go back paragraph by paragraph and make sure that the internal conflict was present, was related to the external problem and that it grew over the course of the story.

Pacing. I separated one long chapter into two chapters, making sure the ending of the first chapter was a cliff-hanger and the beginning of the next chapter had a good hook.

Verbs. Yes, verbs. As we all know by now, strong verbs make for good story language and a strong voice. And I was doing pretty well. But I noticed in this chapter that I was slacking off some. For example, I replaced “They stared” with “They gaped”, and later with “They gawked.” Subtle differences, yes, but important.

Characterization. I am confident that A is a strong character. But what about B, C, D, E, F, G? As I read through, I am looking for places to characterize them better.

When is a Novel Revision Finished?

Um, never. I think I could endlessly revise a novel and my friends will attest to that. But at some point, I’ve done all I can do without more feedback. With this final pass through, I’ll be at that point. It will be time to send the novel out into the world for someone to read and evaluate. Does that mean I am finished with revisions on this particular novel? Doubtful. Bu until some fresh eyes catch weak areas, I can’t see anything else to do. Soon, very soon, it will be on its way.

You're thinking that title must be a typo, aren't you? It isn't, I promise. :) Frustration is awesome.

You're thinking that title must be a typo, aren't you? It isn't, I promise. :) Frustration is awesome.

Sure, as writers, we want NOTHING to do with this emotion. Between manuscripts returning from critique partners with their guts ripped out to a book review that compares our writing skill to that of a lobotomized hamster, frustration awaits at every turn.

We develop coping strategies to avoid it: pep talks before opening email. Chugging Diet Dr. Pepper by the six pack. Sucking on the sweet innards of M&Ms, pretending each one contains a Muse's orphan tears and gives us writing superpowers. *coughs* What, you don't do that? Erm, yeah....me neither.

So, on the keyboard side of things, frustration sucks. But on the page? MAGIC.

Frustration--that hair-pulling, chair-kicking delight--is what drives our novel. It juices our plot, makes our characters twitchy and unfulfilled, and glues the reader to the page. Keeping characters from their goals creates Frustration (AKA Tension, the Heartbeat of a story).

Frustration--that hair-pulling, chair-kicking delight--is what drives our novel. It juices our plot, makes our characters twitchy and unfulfilled, and glues the reader to the page. Keeping characters from their goals creates Frustration (AKA Tension, the Heartbeat of a story).

So while WE try to avoid this emotion, it's important we make sure our CHARACTERS don't. In this state a character reveals who they really are. Frustration is emotional GOLD, forcing them to ACT, which pushes the story forward.

Of course, no two people express their Frustration the same way, and neither should characters. Understanding their Emotional Range (how they express emotion and to what degree) is key to creating believable emotion.

When up against a wall, a character might:

Retreat inward

Run from the problem

Try to manipulate/influence

Give up

Get angry

Get angry

Vent out loud

Cry

React with violence

Feel depressed

Lay blame

Seek revenge

Take out anger on others

Berate themselves

Ask for help

Analyze what happened in hopes of understanding

Fall into a bottle, feed an addiction, drink orphan tears

Act like it doesn't matter

Bounce back & try again

Do Reactions Fit the Character?

Do Reactions Fit the Character?

A hardened criminal character isn't going to ask for help or have himself a weepy moment. A skittish, shy teen isn't about to rant and rave in the middle of the school, and I doubt a Kindergarten teacher would whip out her AK-47 to get her rage on. These things don't belong in their Emotional Range.

Who our characters are at their core--their values, their sense of self, their confidence levels and insecurities--dictate how they behave. The hardened criminal is gonna get himself some reve

I saw the final Harry Potter movie last week. I think I'm in mourning. I'm also still pondering the tension piece of writing, and how important it is. Put those two pieces together, and you (or at least I) get an interesting question: How did Rowling manage to keep us turning those gajillions of pages through a 7-book series? I know there were long narrative stretches, backstory, and other potentially skippable parts. How did she do it? So I re-read book 5 and I noticed some really great tension-building techniques that we all should be applying.

- Add excitement/conflict to potentially boring scenes. Take the scene at the dinner table when Sirius tells Harry all that’s been going on in the wizarding world while Harry was stuck at the Dursleys. Dinner table + backstory should = boring. But it doesn't, because a couple of tension-building subplots are threaded through it: a) Harry and Sirius are both angry at Dumbledore and the reader doesn’t know why, and b) information is deliberately being kept from Harry--information that directly effects him and he should have access to. Tension comes in the form of information that the reader and character don't have and strong character emotion because of it.

- Make the setting interesting. Even though this scene happens at a dinner table, the kitchen in question is located in a grimy, grungy, nasty dark wizard’s house that’s occupied by evil creatures and a hostile house elf. Knowing that anything crazy could happen makes the scene more appealing. Granted, every scene can't occur in a Grimmauld Place, but for situations like these, see what you can do to add interest, humor, fear, or uniqueness to the setting.

- Make sure that other things are going on. While they’re sitting around talking, Tonks is transforming her nose into various shapes for entertainment purposes. Peripheral humor is still funny and always welcome to the reader. Also, Ginny is rolling butterbeer corks on the floor for Crookshanks. This bit isn't critical to the overall plot, but it adds some action to a scene where there's not a whole lot happening.

- Delay exciting/important events. In my copy of book 5, Harry learns about his disciplinary hearing on page 33. The actual hearing doesn’t happen for one hundred pages. By delaying that important event, the tension stretches out, and the reader continues reading because they can't put the book down until they find out whether or not he's going to be expelled.

So What? That’s the question you must get past in your fiction. Why should a reader care?

Keep Reader’s Interest: Make Everything Matter More

The best way to make a reader care about your story, your novel is to make things matter more, put more at risk, up the stakes.

Personal Stakes

This can be accomplished on multiple levels. The first is a personal level. We must care about your character for some reason. A typical kid in a typical school is boring. Why do we care about this character?

- Moral Character. Because they are honest or loyal, kind or brave, respectful or trustworthy, loved by one and all. Some character trait must endear them to us and that usually has to do with a high moral character, at least on some level. And of course, your story will challenge that moral fiber

- Someone Loves Them. It’s important that you Show-don’t-Tell that someone loves this character. We like likeable folks; especially if you have a rough character, someone must let the reader know that the character is still lovable. It might be just a dumb animal who loves and is faithful to Mr. Rough Mouth, but it must be something or someone.

Public Stakes

In the world of your story or novel, something must also be happening that has consequences. If A doesn’t figure things out, then X, Y and Z will happen and those things add up to one major catastrophe for the city or nation, the neighborhood or the ranch, the business or the spy endeavor.

In the world of your story or novel, something must also be happening that has consequences. If A doesn’t figure things out, then X, Y and Z will happen and those things add up to one major catastrophe for the city or nation, the neighborhood or the ranch, the business or the spy endeavor.

- Stretch out the tent pegs. Give the story’s consequences a wider influence than you had originally planned. The events reach tentacles into the very fiber of society (on whatever level is appropriate).

- Price of Success. What’s the price your character must pay to succeed in their quest? How can you increase the price in terms of moral character or personal relationships? How can you make the character hurt more, while also taking the results to a wider field?

- Self Sacrifice. Funny–if a character volunteers to endure something, we admire him/her. If they are forced to do it, we sympathize, but we don’t admire them as much. A willingness to pay an unusually high price will raise the stakes.

- Extreme Effort. Here’s where a story can easily go wrong: you make the trials and ultimate resolution too easy. Instead, push your character to his or her physical limits, mental limits, emotional limits. You love this character that you created, yet you MUST tighten the screws in every way possible, make them suffer, force them to fight for every inch of success. Whatever trials and conflicts you’ve thrown at them, intensify it. Think about extreme sports: the triathon combines on three hard races for a grueling competition. And yes, it’s no accident that upping the public stakes can hardly be separated from its impact on your character.

.png.jpg?picon=4257)

By: Diana Hurwitz,

on 6/17/2011

Blog:

Game On! Creating Character Conflict

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

conflict,

fiction,

writing,

characters,

craft,

optimism,

scene,

tension,

decisions,

pessimism,

Add a tag

Is the glass half empty or half full? It depends on your outlook, unless your character is nit-picking and breaks out a ruler to measure fractions of millimeters to prove it one way or the other.

It is conjectured that optimism drew us forth from caves to explore the wild. We would not have evolved without it and would not continue to thrive without it. Imagining a better world inspires us to work toward one. Optimism allows us to take a seat in a car, train or plane. It encourages us to date, walk down the aisle and parent. It inspires inventions, technology and religions.

Optimism is based on hopes of a future reward whether it is tied to a relationship, a resource, or global climate change. If there is no hope, why bother? Ironically, not all religions are fueled by optimism. Some take a very pessimistic view of the world. It is only by jumping through a certain set of hoops in this world that you can achieve ascendance to a better world. It offers the carrot of eternal life in a beautiful world while existing in a terrible world.

Optimism allows Dick to project positively into the future and to examine “what happens next” before it happens. The mind is capable of considering what has happened, what is happening now and what will happen in the future. The more positive Dick feels, the more likely he is to attempt something. The more negative he feels, the less likely he is to attempt it.

Your protagonist, antagonist, friends and foes can view the overall story problem and scene obstacle from one of two positions: (1) They can believe they will be successful no matter how many attempts it takes, or (2) They can believe they will fail and will be frustrated by how many attempts are made. Overturning what they believed creates tension and new complications.

Pair an optimist and a pessimist and they will disagree and irritate each other as they work to overcome the obstacle. Optimism and pessimism can be the obstacle in a tense conversation. If Dick needs Sally to adopt his point of view, she can fight it tooth and nail out of fear of negative outcome. They can be talking about breaking into someone’s office, taking a vacation to Istanbul or trying to stop a serial killer from reaching his next target.

The level of optimism Dick has will affect his decisions when he is faced with choices. It’s easy if Dick has to choose between a perceived negative and a perceived position option. He will, of course, jump on the positive option even if it ends up being the wrong thing. If his perception is faulty, you have further complications.

It’s interesting to give Dick two negative options (both with impossible outcomes) or two positive options (both with favorable outcomes). You define his character by showing how he reaches a conclusion.

Most of the time, once Dick has decided on an option, he will feel better. He will reinforce, in his own mind, the rightness of choice A and will begin to devalue choice B.

In my WIP, I’m looking for mini-conflicts among characters. I want to keep the tension high throughout. Donald Maass, agent and author of Write the Breakout Novel, says, “Tension on every page.”

Ongoing Conflicts. These mini-conflicts are the stuff of everyday life:

Ongoing Conflicts. These mini-conflicts are the stuff of everyday life:

- The ongoing battle between teacher/student over chewing gum.

- The ongoing battle between brother/sister over hanging up towels in the bathroom.

- The irritation of being the only one in the household to notice that the trash needs to be taken out.

You should give these conflicts only a tiny fraction of space, but they will repay you in big ways as they make the character, setting and plot more concrete and realistic.

Scene beats. Mini-conflicts might just be the tiny beats of a scene. It’s the small actions, dialogue, reactions, movements that are required for a character to physically move in space and interact with other people and his/her environment. You can build in min-conflicts in something as simple as making a cup of coffee. The tap water is too hot/cold; the coffee grounds spill; all the coffee cups are dirty; the sugar bowl is empty and the creamer is sour.

NonFiction BookBlast

Sunday, June 26, 2011. 8-10 am.

ALA Conference in NOLA.

NonFiction BookBlast

Sunday, June 26, 2011. 8-10 am.

ALA Conference in NOLA.

When I get a writing idea, I usually live with it awhile before I start working. ("Awhile" could be two weeks or two years.) I never sit down right then and plough into it.

Except sometimes. Especially if it has been awhile between good ideas. This was one of those times. I had a character I already knew very well (Nilla) and more than enough scenes for a 32 page book. I banged away at the computer far into the night. What's more I finished it! In one sitting! I went to bed, wondering which of my editors I would "grace" with my genius.

I wait a couple of days before re-reading a picture book manuscript. You know, long enough to catch a bug here and there. I figured Camp K-9 needed so little "de-bugging," I would mail it that day.

Hmm. This manuscript seemed unusually long for something that was supposed to be under 800 words. (I know editors like them shorter than that, but I have never which managed less than 775.) I read on and on, then hit the word count command.

2500 words. Gulp.

I wasted three pages (usually the length of the entire manuscript) with a story "frame": Nilla belonged to a little girl and this would be the first time they had ever been apart, and there was a wizard who turned the kennel into Camp K-9 every night and blah, blah, blah. What was I thinking? I never use story frames, not even in novels.

Things went from bad to worse when I realized that I had written a YA picture book for seven-year-olds. For thirty seconds, I considered turning it into a graphic novel...until I remembered that I

can't draw. And what editor would buy a graphic novel about a Valley Girl dog and her friends? Who would read it?

My hand hovered over the delete key. I didn't want to give up on Nilla. I liked the title Camp K-9. I would simply write about Nilla as a puppy.

The trick to writing a picture book (if you are not your own illustrator) is to include a lot of action scenes to give the artist something to work with. After three hours I had only two Nilla puppy memories. She would fall asleep across your shoes, thus trapping you in place until she woke up. And whenever you came home, she would be so excited she would pee at your feet (not on them, thank goodness.) Not great visuals. And worse, no story.

Sigh. I deleted Camp K-9, except for the title. There would be a book called Camp K-9 some day. Just not this day.

Months went by with Camp K-9 in my mental "creative crockpot." I had a critique group meeting coming up, and no manuscript to contribute. I re-opened the empty Camp K-9 file.

Maybe the real Nilla was getting in the way of a fictional one. I changed her name to Roxie, the name of the boxer who lived down the street. I suddenly realized that almost everyone I knew had a dog.

A dog with a human name; apparently people don't name dogs Spot and Skippy any more. I quickly had a roster of dog campers with names like Bea and Hannah. I didn't specify breeds for any of the dogs, save two; Lacy, who was a standard poodle who lived across the street. Since I planned for her to be "the mean girl," I thought the combination of a breed known for being "a chick dog" along with her sweet name, would be hilarious. The other "real dog" was Pearl the Pug, who incidentally belongs to Emmy of A Tree for Emmy fame.

Once, I had those dog names, I could see them, doing all sorts of things that canine campers would do; hiking, swimming, making paw-print crafts. Yeah, I gave my future illustrator a lot to work with.

I counted the days unt

Pulling readers into your story and escalating their interest requires creating, building and maintaining the right level of tension. However, sometimes as an author you might have the tendency to sabotage the tension you’ve created by giving into your character’s desires.

For example, to create tension in your story you might put your character in a precarious life and death situation that they really want to get out of fast. Instead, of building on that tension you might decide you don’t want your character to have to endure their emotional suffering too long, so you give them a fairly quick escape. When you do, you often relieve the story tension (and reader’s interest) prematurely. Building the optimal amount of tension often requires dragging your character through unbearable long-lasting tortures (physical, emotional or intellectual). Just when things seem like they couldn’t be any worse for your character, what you really need to do is find a way to make them even worse.

Of course, readers can reach a point of tension overload, which can also cause them to stop reading. So you have to be careful not to overdo their suffering and you occasionally have to relief some of the tension so readers can breathe their own sigh of relief. It in essence becomes a balancing act of creating and building tension levels to a high, sustainable point, but not too high and for not too long.

But ultimately, the point is that no matter how much you love the characters you’ve created, don’t give in too early to their pleas for help. Make them suffer a bit longer, and your readers will love you for it.

What are your thoughts on building story tension?

Image by Carl Glover

Most stories hinge on the question of attraction versus repulsion. A protagonist is either kept from achieving something he really wants to achieve or works to prevent something he can’t allow.

There are many motivators both tangible and intangible. They can be a desired object, a position, a return favor, praise, time spent together, a puppy or promise of a leisure activity. The reward can be immediate or in the future. Too far in the future and both reward and punishment lose their impact. That is why the story and scene stakes should be more immediate.

The reward must also be meaningful to a character. We are all motivated by different things. We all like and need different things.

If you promise an introvert a party or a starring role in a play, they will most likely walk away.

If you promise an extrovert a week alone on a tropical island, they will likely decline unless the island has buried treasure.

Most of your characters, at some point, will do something either out of hope of reward or fear of punishment.

Dick might work toward solving the story problem out of hope of reward. He will gain something he very much wants: the girl, the job, the presidency or world peace.

Sally might work toward the story or scene goal out of fear of punishment or retaliation by an angry parent, aliens or an evil mob boss.

There are many types of rewards: self esteem, the esteem of others, connection, friendship, money, position, power, fame or an adrenaline rush.

The most powerful is financial gain. Characters are willing to dress up in costumes and act silly to gain money. They are willing to stand out in the rain with a sign and beg for it.

If Dick is in debt, he may be willing to lie, cheat, steal and kill to get money. Money encourages characters to gamble, to invest in risky stocks, to commit murder in a Mystery. It can also motivate a child to do his chores or a worker to try harder to get a raise.

If Dick values esteem over money and offering to pay him doesn’t work, offering to publically praise him will.

Jane may resist the goal because she does not want the reward, strange as that may sound. Offer Jane the carrot of something she does not want, and you have the opposite effect than the one you desired. Offer Jane a punishment she’d enjoy and you’ve failed again.

0 Comments on Conflicts of Attraction as of 1/1/1900

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 11/7/2010

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

conflict,

book,

fiction,

novel,

scene,

write,

tension,

how to,

novel revision,

Add a tag

When, How, and Why to Cut from Scene to Scene

Join us on Facebook for a discussion of scenes.

Importance of Scene Disasters

Are you personally a peace maker? Do you try to smooth out conflict among your friends? Are you in trouble when you try to write fiction!

Scenes must end in disaster, at least a majority of the time. Fiction is about conflict and that means that scenes should end with conflict and tension. The situation just got worse for the main character.

November discount: 10% off orders of $30 or more. Use discount code: scene.

November discount: 10% off orders of $30 or more. Use discount code: scene.

I’m emphasizing this point by giving it a post of its own, it’s that important. Too many authors begin first drafts loving their characters so much that nothing bad happens.

Boring.

Something must change by the end of a scene:

- New information comes to light and we suspect it’s important information.

- Someone’s feelings/emotions change for the worse.

- A character fails to obtain something.

- Partial success, but it only brings discouragement; the cup feels half empty, not half full.

Make sure that every single scene has conflict and ends with something worse than before.

Jill Corcoran blogged about

ways to activate your story recently, using Gayle Forman's novel,

If I Stay, as an example of a great beginning. She wrote:

Gayle does not start the book at the moment of the car crash. We first see the family together, we actually fall in love with the main character and her family so when the car crash happens, we are devastated along with the main character. Gayle starts the first line of the book with an intriguing sentence….a sentence that activates us to pay attention to this first meeting with the main character’s family. That foreshadows the doom and gloom to come:Everyone thinks it is because of the snow. And in a way, I suppose that’s true.

But the reason that sentence works, really works, is a tiny little piece left out of the quote. Here's how the novel really starts:

7:09 A.M.

Everyone thinks it was because of the snow. And in a way, I suppose that’s true.

Do you see it? It's there in big bold letters. The ticking clock.

Because that clock is there, we know to combine "it" with a timeline. We know something is going to happen soon. We know "it" is bad, because why bother with a clock that precise if it isn't a countdown of sorts. And we know it has to do with the snow. Sort of. So now, we're hooked. We have to know what "it" is, and why it wasn't completely to do with the snow. And we have an implied promise that it isn't going to take the author long to get there.

As readers, we haven't thought through any of this. It's simply there, in the back kitchen of our consciousness, if I may borrow the phrase from Kipling. And once it's there, it has a hold on us.

Even a reader who wouldn't normally read a book about bow-tie-wearing dads, or little brothers who let out war whoops, or mothers who work in travel agent's offices--who cares about all that stuff at the beginning of a book, right?--is going to be curious enough to read a little further. Sure enough, Forman delivers on the promise. At 8:17 a.m., a dad who isn't great at driving gets behind the wheel of a rusting buick and.... Well, we know we only have a few more pages.

Even after the accident, the clock doesn't stop. It continues until 7:16 the next morning, because Mia is trying to make her decision, and all along, all through the twists and turns and intricately woven scraps of memory and medical magic, that clock keeps us focused on the fact that something life-changing is going to happen. Soon. Soon. So you can't stop reading.

Building Suspense with a Ticking ClockHaving an actual Jack Bauer 24-style ticking clock only works if something momentous is going to happen:

- An event, accident, or necessary meeting

- A deadline given to prevent consequences

- An opportunity that can, but shouldn't, be missed

- Elapsed time from a precipitating event

The Clock

The clock is mainly a metaphor. You can use any structural device that forces the protagonist to compress events. It can be the time before a bomb explodes or the air runs out for a kidnapped girl, but it can also be driven by an opponent after the same goal: only one child can survive the Hunger Games, supplies are running out in the City of Ember....

One of the first lessons a creative writer learns covers GMC: Goal, Motivation, Conflict. Without a viable GMC combination, it's impossible to create characters that leap off the page and burn themselves into your heart, so GMC is at the core of every memorable work of fiction. Not only does each major character have their own GMC, but ideally, each relates to the major theme and they all come together to govern the characters' actions in the climax.

- (G)oal. What the character wants and strives for to move the story forward. It must be difficult to achieve and come with its own inherent challenges and obstacles, and each choice and character change through the novel must make it harder or easier to attain that goal.

- (M)otivation. The logical, believable reason or reasons the character wants that goal more than anything else in the world and is willing to work toward it instead of giving up when the going gets tough.

- (C)onflict. The seemingly impossible obstacle or obstacles that will keep the character from attaining the goal until she has proven herself worthy through struggle and hard choices--and the way you keep your readers turning pages.

Ideally, GMC is both internal (emotional) and external (physical) for every character, which provides them with depth and believability. More ideally, the internal and external GMCs will oppose each other. And most ideally, the GMCs for your critical characters are also in opposition. Those last two steps ensure that your novel not only contains conflict, but natural tension on every page. But bear in mind that natural does not equate to realistic. To create tension, conflict in a novel must be magnified, just as characters must be larger than life.

Tension, according to literary agent and author Donald Maass, is what makes

a novel breakout, what makes it sell. He explains it like this:

All of this comes down to opposition of one type or another:

- The character's external goal conflicts with her internal goal.

- Circumstances put two of her external goals in conflict with each other so she must choose between them.

- Another character she loves wants something that conflicts with her own goal.

- Attaining one suddenly changes circumstances and makes achieving the other impossible.

- Achieving one would have an impact on others her conscience would not allow.

The options for creating opposition are nearly infinite, but they must arise naturally from the GMC to be believable and truly compelling, and there must be an equally compelling reason why those circumstances occur. Similarly, the reader must understand and believe the reason why opposing characters are thrown together and kept together in a situation of conflict. Externally, their characteristics and goals must be interwoven into the novel's plot so they physically can't evade the conflict that is thrown at them. Internally, their motivation must make it impossible to give up.

To set up this kind of situation, as with anything in your manuscript, it helps to start with a macro view. Debra Dixon provided a simple chart in her excellent book, "

GMC: Goals, Motivation, and Conflict."

Following the in-depth article Emotion Makes the Plot article about tips for creating emotion in your characters, I offer the following.

Following the in-depth article Emotion Makes the Plot article about tips for creating emotion in your characters, I offer the following.

Use of the following behaviors, which impede effective communication, are effective for creating conflict and tension and deepen character:

Walking away

Sarcasm

Blame

Short Temper

Withdrawal

Not listening

Talking over

Looking away

Shouting

Anger

Criticism

Intellectualizing

Debating the complaint

Threatening to leave

Counter-complaints

(List is thanks to my dear friend, Teresa LeYung Ryan, and Emillo Escudero. Thanks!)

Gotta run. More later.

Hope these help....

View Next 2 Posts

I recently saw an advanced screening of the film The Spectacular Now. This honest and moving film is based on Tim Tharp’s YA novel (which also happens to be a National Book Award Finalist). The story follows Sutter Keely (Miles Teller), a high school senior determined to live in the present and forget the future, as he stumbles from one good time to the next. With a flask in one hand and his happy-go lucky attitude in the other, Sutter gets involved with the sweet and shy, Aimee (Shailene Woodley). But disaster is coming … because who can live in the present moment forever?

I recently saw an advanced screening of the film The Spectacular Now. This honest and moving film is based on Tim Tharp’s YA novel (which also happens to be a National Book Award Finalist). The story follows Sutter Keely (Miles Teller), a high school senior determined to live in the present and forget the future, as he stumbles from one good time to the next. With a flask in one hand and his happy-go lucky attitude in the other, Sutter gets involved with the sweet and shy, Aimee (Shailene Woodley). But disaster is coming … because who can live in the present moment forever?

Ongoing Conflicts. These mini-conflicts are the stuff of everyday life:

Ongoing Conflicts. These mini-conflicts are the stuff of everyday life:

So well said, Ingrid. It reminds me of Hitchcock and this views on suspense. If there is a bomb under the table, a scene’s tension will be heightened, the purpose accomplished. The bomb does not need to explode. It might for other reasons. But not for suspense. An explosion only diffuses the tension.

Great post! I love the unfulfilled expectations aspect though an author takes a gamble with thwarting a reader’s expectations. i like to guess what will happen, as you mention, but I don’t always want what I guess to come to pass. I like a surprise that feels inevitable. I need to see this movie!