new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: #plot, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 10 of 10

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: #plot in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Disunity obstacles motivate characters to offer resistance to, or agree to assist with, another character’s scene goal or overall story goal.

Motivating your primary characters is essential to a well-developed plot. Motivating your secondary characters, the friends and foes, adds depth.

1. Competition. Wishing to one-up, surpass, or defeat someone can be mild or taken to laughable, even deadly, lengths. The competition between characters can be out in the open. They know they are competing for the woman, the antiquity, the position, or the country. It can be an undercurrent that flows between two characters who aren't even aware this is their motivation.

2. Jealousy and resentment. How long has that pot been boiling? What causes it to overflow?3. Gossip, rumors, and backbiting. I am struck by how often characters exist in a bubble. They are part of the wider world. What they do and say will be observed, discussed, and perhaps acted upon.

4. Blackmail. Secrets are the lifeblood of good suspense. They do not have to be conspiracies or fatal. They only require that the character feels shame about something they don't want other people to know. Giving another character the power to expose them adds tension.

5. Differing goals and needs. This conflict can be mild or ruin a relationship, a heist team, or derail a war.

6. Dislike, hatred, or anger. Few character types are overt in their expression of these emotions. A subtle level can lead a friend or foe to fail to cooperate, break a promise, or cause them to undermine every goal your character has.

7. Love for something or someone. Love unites. However, love can prevent a character from taking an action that will hurt someone they care about. The threat can be deadly, but they will not risk it. Love can also motivate someone to go beyond normal limits and take uncharacteristic risks. It can provide the push to keep them moving toward their goal or add the resistance to doing what needs to be done.

8. Friendship and loyalty. Few characters are completely friendless or free of bonds of loyalty. Who are your characters beholden to? Who will they betray? What is the price of that betrayal? Who will they catch a grenade for?

9. Opposing methods of negotiating the world. Some are mavericks. Some are conservatives. Some are willing to do whatever they want regardless of the cost. For others, the cost is too dear. Putting opposites together heightens the tension. Every decision and action will create conflict.

10. Shallowness versus depth of connections. How easy is it for your character to walk away? What is the cost? Deepening their connections heightens the stakes.

Motivation drives each character in your story. They may know what motivates them. They may be completely unaware. The other characters may be aware or completely unaware of why characters behave as they do.

Tweet this: Motivation transforms your cardboard characters into flesh and bone.

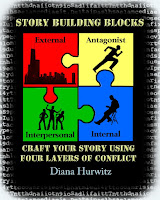

For more about how to craft characters, pick up a copy of Story Building Blocks II: Crafting Believable Conflict, available in paperback and E-book and Story Building Blocks: Build A Cast Workbook, available in paperback and E-book.

Disunity obstacles motivate characters to offer resistance to, or agree to assist with, another character’s scene goal or overall story goal.

Motivating your primary characters is essential to a well-developed plot. Motivating your secondary characters, the friends and foes, adds depth.

1. Competition. Wishing to one-up, surpass, or defeat someone can be mild or taken to laughable, even deadly, lengths. The competition between characters can be out in the open. They know they are competing for the woman, the antiquity, the position, or the country. It can be an undercurrent that flows between two characters who aren't even aware this is their motivation.

2. Jealousy and resentment. How long has that pot been boiling? What causes it to overflow?

3. Gossip, rumors, and backbiting. I am struck by how often characters exist in a bubble. They are part of the wider world. What they do and say will be observed, discussed, and perhaps acted upon.

4. Blackmail. Secrets are the lifeblood of good suspense. They do not have to be conspiracies or fatal. They only require that the character feels shame about something they don't want other people to know. Giving another character the power to expose them adds tension.

5. Differing goals and needs. This conflict can be mild or ruin a relationship, a heist team, or derail a war.

6. Dislike, hatred, or anger. Few character types are overt in their expression of these emotions. A subtle level can lead a friend or foe to fail to cooperate, break a promise, or cause them to undermine every goal your character has.

7. Love for something or someone. Love unites. However, love can prevent a character from taking an action that will hurt someone they care about. The threat can be deadly, but they will not risk it. Love can also motivate someone to go beyond normal limits and take uncharacteristic risks. It can provide the push to keep them moving toward their goal or add the resistance to doing what needs to be done.

8. Friendship and loyalty. Few characters are completely friendless or free of bonds of loyalty. Who are your characters beholden to? Who will they betray? What is the price of that betrayal? Who will they catch a grenade for?

9. Opposing methods of negotiating the world. Some are mavericks. Some are conservatives. Some are willing to do whatever they want regardless of the cost. For others, the cost is too dear. Putting opposites together heightens the tension. Every decision and action will create conflict.

10. Shallowness versus depth of connections. How easy is it for your character to walk away? What is the cost? Deepening their connections heightens the stakes.

Motivation drives each character in your story. They may know what motivates them. They may be completely unaware. The other characters may be aware or completely unaware of why characters behave as they do.

Tweet this: Motivation transforms your cardboard characters into flesh and bone.

For more about how to craft characters, pick up a copy of Story Building Blocks II: Crafting Believable Conflict, available in paperback and E-book and Story Building Blocks: Build A Cast Workbook, available in paperback and E-book.

.png.jpg?picon=4257)

By: Diana Hurwitz,

on 3/10/2016

Blog:

Game On! Creating Character Conflict

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

#amwriting,

#character,

#plot,

#conflict,

#writingtips,

#psychgology,

#worldbuilding,

#control,

#motivation,

@Diana_Hurwitz,

#boss,

#employee,

#power,

Add a tag

|

| WHO'S THE BOSS? |

I have to thank a friend for inspiring this one, though I’ll withhold names to protect the innocent. My friend, let’s call her Jane, works in an office where the boss’s wife comes in periodically to make sure things are done her way. She isn’t actually an employee, nor is she an expert in the business he conducts. She just likes to meddle and throw her weight around to feel powerful.

Tweet: Family run businesses can be an entirely different breed of viper’s nest. #storybuildingblocks #writingtips

Unlike the cogs in the corporate hierarchy that are easily removed and replaced, the family run business is full of emotional landmines.

If Dick’s father is the nominal head of the business, theoretically he should be in charge. But what if he isn’t?

What if Dick’s Mom wears the corporate pantsuit even though she doesn’t actually work there? It will cause aggravation if not outright abuse for all who work for them. It is a very uncomfortable work environment. The rules can be disregarded at whim and the hierarchy ignored when the untitled boss gets involved. The changes she makes are implemented without warning or consideration for those who actually have to show up and do the job every day. They are enforced even though they create headaches for those who have to perform the tasks.

Jane will go to the office every day primed with anxiety. When will the saboteur show up next and what impossible demands will she make? Because the reward system is illogically skewed, Jane won’t be certain that her hard work and dedication will be appreciated, so how hard should she try? Should she stay or go? Depends on her situation and how good the pay and benefits are. How much is Jane willing to sacrifice for material reward when every day feels like a swim in a shark tank? How much abuse is she willing to endure before she quits or pulls out a revolver?

How does the uncertainty affect the son Dick? How frustrated will he grow with his spineless father when he witnesses his mother’s torture of the employees? How firm can he get with his impossible mother? Will Dick grow and learn to stand up for himself against the female bully or will he repeat the enabling pattern?

What if Dick’s sister Sally also works at the firm? They have grown up being pitted against one another. Who is the favorite child for which parent? The dynamics shift depending on the answer. If Dick is Dad’s favorite and Sally is Mom’s favorite, then Dick has a real problem. His succession as head of the business isn’t assured. Mom may choose Sally to take over. If Sally is Dad’s favorite and Dick is Mom’s favorite, then Sally has a problem. She can have Dad wrapped tightly around her little finger, but if Mom wields the power and isn’t too fond of her simpering daughter, Sally is in a no-win situation. If the parents continually play out their antagonism toward one another through their son and daughter the waters get hurricane choppy. If Mom dies, then Dad is free from her oppression and the work environment can become an entirely different place. If Dad dies, and Mom takes over or the business is turned over to Sally instead of Dick, the situation can disintegrate further. If the siblings enter a turf war over it, the conflict heats to a boil.

How many employees will abandon ship? How many will stay? How can the company survive if the internal structure is unstable?

The addition of sibling and parent dynamics to any story situation raises the stakes and changes the playing field significantly.

The conflict could be a mild distraction while Dick is trying to save the planet or find the kidnapped girl.

The conflict could be the core of a literary tale of deadly dysfunction.

The conflict could be the source of an intense thriller or suspense.

The parent/child scenario could be a factor in a YA novel. The parents could be running a gas station, a major corporation, a village, a country, or a wolf pack.

In your story, who is the boss? Who are the powers that be? Who makes the ultimate decisions? The more dysfunctional the situation, the higher the story stakes.

For more on crafting conflict to create tension, pick up a copy of Story Building Blocks II: Crafting Believable Conflict available in paperback and E-book.

.png.jpg?picon=4257)

By: Diana Hurwitz,

on 12/30/2015

Blog:

Game On! Creating Character Conflict

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

#amwriting,

#bad choices,

#plot,

#conflict,

#writingtips,

#characters,

#screenwriting,

#dennis brown,

#mistakes,

#ruleoflife101,

@dennisbrown,

Add a tag

Dennis Brown in his book Rule of Life 101 defines the difference between bad choice and a mistake thusly:

“A mistake is innocent, a bad choice is not. A mistake is being completely oblivious to the error being made. An example would be telling someone your name and them pronouncing or spelling it wrong. Or giving someone the wrong phone number because you just got a new number and it slipped your mind. These are examples of mistakes. A bad choice is being totally aware of the error being made and choosing to do it anyway. Say for instance your boyfriend or girlfriend was sleeping with your best friend. A bad choice is knowing something is wrong or hurtful and doing it anyway.”

In any story, the critical turning points are either actions or decisions. Bad choices or actions result in goal failure. Mistakes cause conflict along the way. Take a look at your work-in-progress. Have your characters made bad choices or mistakes? How did they complicate the overall story problem?

If the inciting incident is a bad choice, Dick is forced to take steps to repair it. The key turning points will show the progress toward and steps away from repairing his life, relationship, or situation to the status quo.

If the inciting incident is a mistake, Jane will have to make amends. In the first turning point whatever she has tried doesn’t work. She will have to approach the problem from a new angle. At turning point two, that angle didn’t work either. In fact, Jane compounded the mistake, perhaps by making a second mistake. In the third turning point Jane will realize the right course of action that will restore the story balance. In the climax, she makes amends and all ends happily, usually.

The caution I want to offer is this: it is hard to root for a character that continually makes bad choices and mistakes. One or two sprinkled throughout a story can drive it. However, if the story is riddled with them, it becomes abusive.

I’m reminded of a recent television series I watched. After two seasons with a main character who continually made mistakes and bad choices, there was no growth. He never caught on that he was the problem. It made sense that the series was cancelled.

Make sure your characters are not continually making mistakes and bad choices. People who don’t change make poor protagonists, friends, and lovers. It’s okay for the reader to shout “you idiot” once or twice in a story. However, they are likely to burn the book if it happens in every chapter.

As Dennis Brown concludes: “People’s mistakes should be forgiven, and even some bad choices are forgivable, but consistent bad choices should never be overlooked. Know when enough is enough; if you have no boundaries, people have no reason to respect them. A person can’t respect what’s not there to respect. Whether it’s in a friendship, marriage or business relationship, bad choices that lead to adverse circumstances for you should never be tolerated.”

Even if the characters are fictional.

For more information on using conflict to drive plot, pick up a copy of Story Building Blocks: The Four Layers of Conflict, available in paperback and E-book.

.png.jpg?picon=4257)

By: Diana Hurwitz,

on 11/20/2015

Blog:

Game On! Creating Character Conflict

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

#amwriting,

#writing,

#character,

#plot,

#conflict,

#writingtips,

#psychology,

#scene,

#motive,

#story,

Add a tag

Denial is an subconscious defense mechanism. When you ask a two-year old if he took a cookie from the jar (and he knows he will get in trouble for it), he denies it.

Denial is an subconscious defense mechanism. When you ask a two-year old if he took a cookie from the jar (and he knows he will get in trouble for it), he denies it.

Characters deny things for complex reasons: to protect themselves, to protect people they love, to dodge a painful truth, or to deflect blame or suspicion.

When confronted with an internal dilemma or overall story problem, Dick (the protagonist) can choose to accept something or not oppose it at first. He may deny that aliens have landed or that his wife has lost that loving feeling. He may deny that he has cancer. As events unfold, Dick is eventually forced to accept it.

When confronted by information that counters his belief system or faith in someone, a character’s first response is usually denial. Many stories center on his journey as he struggles to accept the truth.

Dick may deny that he is the only one who can stand up to an injustice or a bully, but the overall story problem forces him to do so.

Jane (as antagonist) can see that her plan is failing and refuse to accept it. The reader will be thrilled that she failed.

Dick (as protagonist) can refuse to accept that his cause is lost and push on until he wins. The reader will be elated when he succeeds.

If Jane refuses to believe that Sally is dying, she may plan vacations and purchase air tickets that will never be used. She may insist on trying every far-fetched “miracle cure” on the market while Sally tries to bring Jane back to acceptance that the end is nigh.

Friends and foes chiming in on the issues make the story problem more difficult for the protagonist to succeed and the antagonist to fail. Their own acceptance or denial can create obstacles.

Friends and foes can continue to deny that vampires exist or a friend’s spouse is cheating even when they see the cheaters together.Friends and foes can deny they were at the crime scene, withholding critical information either out of fear or out of malice.

Denial creates conflict and tension as the reader waits for it to resolve. You can use this tactic to drive the story at scene and overall story levels.

To learn how obstacles create conflict for your characters, pick up a copy of Story Building Blocks II: Crafting Believable Conflict, available in paperback and E-book.

Most stories hinge on the question of attraction versus repulsion. A protagonist is either kept from achieving something he really wants to achieve or works to prevent something he can’t allow.

There are many motivators both tangible and intangible. They can be a desired object, a position, a return favor, praise, time spent together, a puppy, or promise of a leisure activity.

The reward can be immediate or in the future. Too far in the future and both reward and punishment lose their impact. That is why the story and scene stakes should be more immediate.

The reward must also be meaningful to a character. We are all motivated by different things. We all like and need different things.

If you promise an introvert a party or a starring role in a play, she will most likely walk away.

If you promise an extrovert a week alone on a tropical island, he will likely decline unless the island has buried treasure.

Most of your characters, at some point, will do something either out of hope of reward or fear of punishment.

Dick might work toward solving the story problem out of hope of reward. He will gain something he very much wants: the girl, the job, the presidency or world peace.

Sally might work toward the story or scene goal out of fear of punishment or retaliation by an angry parent, aliens or an evil mob boss.

There are many types of rewards: self esteem, the esteem of others, connection, friendship, money, position, power, fame, or an adrenaline rush.

The most powerful is financial gain. Characters are willing to dress up in costumes and act silly to gain money. They are willing to stand out in the rain with a sign and beg for it.

If Dick is in debt, he may be willing to lie, cheat, steal and kill to get money. Money encourages characters to gamble, to invest in risky stocks, to commit murder in a Mystery. It can also motivate a child to do his chores or a worker to try harder to get a raise.

If Dick values esteem over money and offering to pay him doesn’t work, offering to publically praise him will.

Jane may resist the goal because she does not want the reward, strange as that may sound. Offer Jane the carrot of something she does not want, and you have the opposite effect than the one you desired. Offer Jane a punishment she’d enjoy and you’ve failed again.

If Jane hates being the center of attention, offering her the spotlight will send her running in the opposite direction.

If Sally prefers vanilla over chocolate, Dick giving her a Whitman’s Sampler for Valentine’s Day won’t earn him brownie points. Baking her chocolate chip cookies instead of sugar cookies won't convince her to do her homework.

Telling Dick he’ll have to stay home with Grandma while his parents go on vacation to Amish Country to shop for antiques won’t exactly break his heart, especially if Grandma is the cookie baking, curfew-ignoring type.

If Dick offers Jane a reward that she considers a punishment, they have conflict. Lets say, Dick suggests they go a Bed & Breakfast for the weekend. Jane might say yes or she might say no. Jane may love B&Bs, but she isn’t feeling particularly fond of Dick at the moment, so she refuses. Going might heal their relationship, but Jane meets internal resistance at the idea of being alone with Dick, so she declines the offer. She will come up with justifications as to why: too much work, conflicting meeting, too exhausted and wants to stay home in her jammies. Jane might agree to go but the confinement of the B&B causes them to fight rather than make up and Dick gets the opposite of what he hoped for. Jane can give in and go and end up having a good time, thus getting the result Dick hoped for but Jane didn't think possible.

If Dick and Jane are forced to work together to solve a mystery, Dick might agree because he loves a good puzzle. Jane might hate puzzle solving but agree because Dick appeals to her sense of justice or fair play. She might be secretly in love with Dick and covet time with him.

If Sally is secretly hoping for an engagement ring for Christmas and Dick buys her a diamond watch, she still received diamonds, just not the diamonds she was hoping for. Dick's next request will most likely be met with resistance if not refusal.

This type of conflict can play out among any set of characters be they friends, relatives, lovers, coworkers, etc. Characters tend to buy gifts, plan vacations, throw parties, arrange date activities and select movies for the weekend based on their wants, needs and personal preferences. This almost always causes conflict unless the two people are entirely in sync with each other in that regard.

Dick may plan a day at the football game, while Sally would rather stay home and watch a Jane Austen marathon. Okay, maybe that's just me, but the point is made.

Jane may plan a surprise party for Dick at work. If Dick hates being the center of attention or if he is trying to pull off a covert action, he will not be happily surprised by the party. It may make his scene goal much harder than he ever thought possible.

If a group of friends decides to go scuba diving in the Florida Keys for the weekend and Jane is either afraid of water or afraid of sharks, she'll refuse to go. No matter how many rewards Sally offers her (free margaritas all weekend, Jimmy Buffett playing at a local bar, lots of hot guys in skimpy bathing suits), none of that will matter to Jane. She could agree to go to the Keys but not scuba dive. The rest of the pack will consider her a wet blanket and refuse to pay for the drinks or refuse to go to the Buffett Concert in retaliation. Or they could enjoy her company so much that they don't care if she joins them in the ocean, as long as she goes along for the trip. If the reward of her company is alluring enough, they might offer to pay for the trip if Jane can't afford it.

Place characters with opposing ideas of reward in a relationship or in a scene and you have conflict.

Next week, we will explore the conflict of repulsion.

For more on using obstacles to create tension in your fiction, pick up a copy of Story Building Blocks II: Crafting Believable Conflict in paperback or E-book.

There are many types of absence: voluntary, forced, temporary, perceived, sporadic, and permanent. Wherever there is absence, there is conflict. Let’s examine ways in which absences can be dramatic, frightening, thrilling, or funny.

The absence of a loved one can create pathos, longing, and sadness. When a loved one leaves temporarily or permanently, it leaves a vacuum that needs to be filled. It may not be filled with healthy endeavors, or the absence can open a door to new opportunities.Absence can cause a momentary annoyance at scene level. Jane had plans to go somewhere with Sally or Dick, but had to cancel. Dick and Sally choose to go together without her. Jane is then wounded because she is so easily replaced. If Jane cancels frequently, then she is no longer considered trustworthy. Dick and Sally might exclude her from future plans and it will make Jane angry.

Voluntary absence from work creates headaches for coworkers. If Dick calls in sick, his work is not getting done. Someone else has to temporarily pick up the slack. He might go to extravagant lengths to hide the fact that he wasn’t really sick. If Jane sees him in town during her lunch hour, he will have to explain his absence. He will either tell the truth or lie. If Jane has it in for him, she will enjoy exposing him and Dick is forced to come up with a deterrent fast. He may agree to do something for Jane he does not want to do. He may take over an assignment for her. She might make him give up his parking spot.

It keeps the plot moving when a scene is resolved in a way that creates a new and more difficult goal. Once Dick has lied to Jane, he will have to maintain the lie. Lies lead to more lies. Dick might have called off to spend one last day with his dying mother. He might have called off to help someone track down a terrorist cell. He might have called off to go to a job interview for a new job. At the end of the day, he will either succeed at hiding his reason for calling off or admit that he was playing hooky. It could be comedic, thrilling or tragic. The reason he called off can be momentous, silly, or simply that he was tired and needed to recharge his mental battery. His absence can have profound consequences or barely make a ripple in the story overall, depending on what you need it to do.At the scene level, Dick could leave the room and give Jane an opportunity to replace or remove something. When he returns, he can notice that his desk has been disturbed. He can either mention it or wait until Jane leaves to search his office. He might shrug his suspicion off, leaving the clue to raise its head later in the story. He might keep tearing his desk apart until he finds the bug or realizes an important file is missing.Dick could leave the scene of an accident and create a story problem, or a complication to solving the story goal that comes back and bites him later. His reasons can be unthinking, an attempt to protect himself, or malicious.Dick leaves a bad date at a restaurant because it was easier to disappear than tell the girl her laugh made him cringe. When he runs into his hapless date later, it will be awkward. If she turns out to be his boss’s daughter, it gets extremely awkward. If he has to work with her, it becomes horribly uncomfortable. If he finds out she is a werewolf, he is in danger.

A character can be voluntarily absent from a conversation, a room, a building, a job, or a planet. There are multiple outcomes to a voluntary absence, but at some point the person typically returns.

Jane jetting off to Aruba without Dick for a month in an attempt to “find herself” creates an overall story problem. When Jane reappears, Dick can be happy about it, unhappy about it or have mixed emotions. Jane’s return can be a good thing or a bad thing depending on how you want to play it and the genre of your story.

In a romance with the typical happy ending, Dick and Jane will overcome the conflicts her voluntary absence and subsequent return create and live happily ever after.

In a literary tale, Jane can return, find out nothing has changed and realize she should have stayed in Aruba with the cabana boy. Dick and Jane can desire to come together again, but realize they really don’t work as a couple, ending on a sad note.

In a mystery or thriller, Jane can return and Dick realizes he preferred life without her. He takes steps to make her absence permanent so he can keep Jane’s inheritance.

Let’s say Jane returned from Aruba after finishing a work assignment that lasted a month or a year. She can return to a spouse, a friend, a child, her parents, a house, a neighborhood, or a job. Her return will affect all of them. Life continued to move on while she was gone. Her return will force her to renegotiate all of her relationships. Friendships and alliances shift over time. Jane’s return can spark jealousy or ignite buried resentment. It can result in renewed love or friendships. The obstacles Jane faces are in trying to fit in again, to redefine her place in the lives she left behind.

Jane might have to move back in with her parents or have her ailing parents move in with her. It can spark a battle of wit and wills. The situation could be comedic, tragic or a sweet literary story of acceptance. This makes a terrific overall story problem or personal dilemma for a protagonist.

Jane might find the balance of power in the company shifted in her absence. She will have to redefine her place in the pecking order. Her coworkers might not appreciate her return, or they might celebrate it because the person who took her place was a jerk.

There are many fun and poignant ways to play with absences.

For more information on using obstacles to create tension, pick up a copy of Story Building Blocks II: Crafting Believable Conflict in print or E-book.

.png.jpg?picon=4257)

By: Diana Hurwitz,

on 8/27/2015

Blog:

Game On! Creating Character Conflict

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

#writingtips,

#craft,

#DianaHurwitz,

#gameon,

#inspiration,

#MythikasIsland,

#whyIwrite,

#amwriting,

#writing,

#character,

#plot,

Add a tag

As I turn 53 today, several recent events converged to make me examine why I write and whether I want to continue writing.

I wrote and published 8 books between 2007 and 2012. I have not written a book in a while and Create Space sent me an email asking if I was still writing.

I had lunch with a friend and we talked about my dry spell and she asked me what would make me passionate about writing again. I have suffered health crisis after health crisis since before I wrote Mythikas Island, which has resulted in a roller coaster of frenzied work and months living as a cat. Health woes certainly contribute to the ambivalence. I began writing poetry and journaling as a young girl. I did not attempt fiction until I was middle-aged. So as I explored the reasons why I started writing books in the first place, a theme developed.

I wrote the Mythikas Island series (I: Diana, II: Persephone, III: Aphrodite, and IV: Athena) for my daughter Anna. She was a teenager and was sick of love triangles in YA books. She said some girls wanted stories that didn’t revolve around guys. Ideas for stories about goddesses and girl power had been percolating for a while and that became the impetus for the Mythikas Island series. Four girls are groomed to be leaders and must save themselves and fight for their future.

I wrote the Mythikas Island series (I: Diana, II: Persephone, III: Aphrodite, and IV: Athena) for my daughter Anna. She was a teenager and was sick of love triangles in YA books. She said some girls wanted stories that didn’t revolve around guys. Ideas for stories about goddesses and girl power had been percolating for a while and that became the impetus for the Mythikas Island series. Four girls are groomed to be leaders and must save themselves and fight for their future.

I wrote the Story Building Blocks (I: The Four Layers of Conflict, II: Crafting Believable Conflict, III: The Revision Layers, IV: Build A Cast Workbook) because I couldn’t find them anywhere when I needed them. I was tired of reading about the story arc and all those motivational tomes. I wanted nuts and bolts and tools for developing plots and characters. I wanted advanced craft lessons. I also wanted to centralize all of my notes on revision, editing, and proofreading. So, I spent several years learning, reading, dissecting stories, and researching. I developed a story architecture theory that made sense to me. This blog, Game On, is an extension of the desire to share what I learn. I also guest post on The Blood Red Pencil, another blog devoted to the craft of writing.

I have studied interior formatting, cover design, and website building. Although far from expert, I have added those skills to my tool kit.

Then I was blindsided with the misdiagnosis of a mystery muscle disease. That led to a year of research and another year of developing that research into a website for the rare disease, Stiff Person Syndrome, which became The Tin Man. It not only has up-to-date information on SPS, but a large section on how to cope with debilitating diseases and resources for patients with rare diseases. Again, things I couldn't find that I needed.

While I haven’t been entirely slothful, there was no book at the end of those two-plus years. Create Space had no way of knowing that, hence the gentle reminder.It turns out, I am motivated by writing things that benefit other people. It is the sharing information and helping that bring me joy. If I inspired one teenager, helped one writer, or educated one patient, I consider all that time well spent.

I’ve always joked to my critique group that my biggest problem is that I don’t need the money and I don’t want to be famous. I admit to being turned off by the business and promotional aspect of publishing, as necessary as it is to being a lucrative independent author. It is an area I would need to research and I’d have to overcome my natural resistance to being in the spotlight and sales promotion. I would also have to work around my physical limitations. I’d much rather sit in a room churning out work and let others worry about what to do with the end product. Alas, successful writer-preneurs are not built that way. So, I have to decide if that is the way I want to spend time.

I attended a funeral yesterday for a friend that made me ponder what I want to do with my remaining time. He died during the adventure of a lifetime, checking off a big item on his bucket list. This led me to examine what I am still capable of and prioritizing my bucket list.

The hubs is going to retire next year in August. After our relocation from Windyana to Adult Disneyland, I don’t know what my days will be like. All those long hours I spent working or sleeping while he was at the hospital will now be filled with different things.

My muses still visit and my characters still chime in with ideas of where they'd like to go, especially my goddess girls. I have more ideas for the Story Building Blocks series. I have a draft of a YA story, and first chapters of many others that I call my Widows & Orphans file including a mystery called The Wicked Stage.

But will they ever see print? Who knows? Once the reno nightmare of the new house and trauma of moving are over, I may put fingers back to keyboard. If for no other reason than to free the characters that haunt me like trapped ghosts seeking the light.

Alliances can drag characters into gangs, criminal activities, and wars. Many tales hinge on divided alliances. Loyalty is often tested.

Members feel they belong to their religious congregations and sports teams. Citizens feel they belong to their city, state, or country. Plots can turn when the governing bodies of those organizations, cities, states, or countries place unreasonable demands on the characters they feel they “own.”

Organizations can be benevolent or menacing.

Dick can force others to belong to his group. He can try to escape a group. Dick can be shunned, punished, or murdered if he attempts to leave a group.

Jane may be willing to lie, cheat, steal, or kill to belong to an exclusive club.

Sally can behave in ways that are detrimental in order to “belong.” She will accept unpleasant circumstances and tolerate unpleasant people in an attempt to “fit in.”

How far is Sally willing to go to belong to, or escape from, a group? This can make a taut Thriller.

If Jane joins a group or club and that group or club starts taking over her life, she has an overall story problem and the situation creates conflict for everyone around her: coworkers, family, spouse, and children.

If a teenaged Sally is desperate to fit into a clique at school, you have another overall story problem. She might humiliate and harm herself to be included. Cliques aren’t limited to high school. They surrounded royalty, emperors, prophets, politicians, actors, and rock stars.

Children feel they belong to their parents, family, or clan. If parents, families, or clans feel they own family members and can tell them what to do and how to live their lives, you have conflict. Perceived ownership can serve as an antagonist motive in a Romance or serve as the basis for a Literary novel.

Lovers feel they belong to each other. If a lover takes the concept of ownership too far, it makes a good Thriller & Suspense problem, a woman in peril novel, or the motive in a Mystery novel.

Devices such as the need to join or the need to break free can be used at the scene level.

Dick may be wrestling with divided loyalties: go to a cousin’s wedding or beg off to chase a clue or meet his dream girl at a public appearance she is making. It also works as an antagonist’s scene dilemma. He can be a mob boss whose presence is expected at a meeting with his second and third in command, but his instincts tell him something is up and that a bust will go down, so he squiggles out of it or does not show up. His minions will not be happy.

Dick’s religious beliefs may keep him from taking a necessary action at scene level. He can wrestle with whether or not it is okay to make an exception, just this once.

Dick may be sick of the idiots populating his tennis club, so he does something to overcome a scene obstacle that will result in his expulsion. The scene accomplished two things: freed him of the ties that were choking him and gained him the clue, evidence, knowledge, etc. that he needed to overcome the scene goal. A further complication could be that those idiots like him so much they ignore the infraction. Dick will have to come up with an even bigger violation to earn his freedom.

This conflict works in any genre. For these and other obstacles that create conflict, pick up a copy of Story Building Blocks II: Crafting Believable Conflict in print or E-book version.

Personal physical boundaries vary from person to person and culture to culture. Some cultures hug, air-kiss, or shake hands and others bow politely.

We’ve all had conversations with people who stand uncomfortably close or those who stand so far away we don’t think they are participating in the exchange. When someone infringes on Dick’s “personal” space, he is forced to back off, push them away or tolerate it until he gets what he needs.

If Dick lays hands on people who don’t like to be touched, he has offended them. If they don’t outwardly respond, they may make an effort to avoid Dick in the future and are unlikely to do what Dick wants them to. If Dick needs to whisper something but the other person stands too far away, they make the exchange of information very difficult to achieve.

If Dick takes a seat in a nearly empty movie theater (train, plane, or bus) and someone chooses the seat next to him several things could happen. The stranger can be obnoxious enough that Dick moves, he can accept the situation, or Dick could become so obnoxious he forces the other person to move. If Dick needs information from this stranger, or if the stranger is targeting Dick, you have conflict.

If Dick is lunching alone and Jane, a stranger, takes the seat across from him, she is either crazed, wants something, or has mistaken him for someone else. Either way you can have fun with it. Characters don't share tables or hotel rooms with strangers unless there is a very good reason for it.

If someone at work consistently encroaches on Sally’s personal space (or work responsibilities), Sally might dread going to work. She may ask to switch offices or even quit. She might take an aggressive approach and escalate the territory war until the other person gives in or quits. This can serve as a scene obstacle or a personal dilemma.

If Dick is an interrogator, he may encroach on a suspect or witness's personal space to intimidate them. Intruding into someone's personal "bubble" is an act of aggression. It could also be an act of intimacy. Who do you really want to have up close and personal? Whose touch is acceptable?

If a sibling encroaches on Jane’s side of the room, she might complain to mom and dad. If that doesn’t work, it can escalate into petty acts of retaliation until one or the other wins, they agree to a truce, or mom and dad step in and separate them. These kinds of disputes can happen between teachers at school, soccer moms on the field, or waiters at a restaurant.

These conflicts are often featured in comedies, but can be utilized in any genre. Two opposing gangs forced to share a hideout in dystopian story works just as well as two enemies sharing a jail cell.

Bowing, handshaking, and hand gestures are the subjects of extensive studies and say a lot about a population and an era. When you write about different cultures, be sure to investigate the ins and outs of social and physical boundaries specific to that region and time period. When you create a fantasy world, this kind of detail can add richness to it.

There are many reasons why one person's "bubble" is wider than anothers based on their past history, trauma, or training. You can use it to define character.