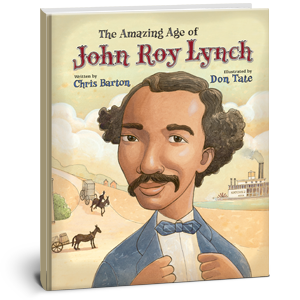

The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch

The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch

By Chris Barton

Illustrated by Don Tate

Eerdmans Books for Young Readers

$17.00

ISBN: 978-0-8028-5379-0

Ages 4-8

On shelves now

“It’s the story of a guy who in ten years went from teenage field slave to U.S. Congressman.” Come again? That’s the pitch author Chris Barton pulled out when he wanted to describe this story to others. You know, children’s book biographies can be very easy as long as you cover the same fifteen to twenty people over and over again. And you could forgive a child for never imagining that there were remarkable people out there beyond Einstein, Tubman, Jefferson, and Sacajawea. People with stories that aren’t just unknown to kids but to whole swaths of adults as well. So I always get kind of excited when I see someone new out there. And I get extra especially excited when the author involved is Chris Barton. Here’s a guy who performed original research to write a picture book biography of the guys who invented Day-Glo colors (The Day-Glo Brothers) so you know you’re in safe hands. The inclusion of illustrator Don Tate was not something I would have thought up myself, but by gum it turns out that he’s the best possible artist for this story! Tackling what turns out to be a near impossible task (explaining Reconstruction to kids without plunging them into the depths of despair), this keen duo present a book that reads so well you’re left wondering not just how they managed to pull it off, but if anyone else can learn something from their technique.

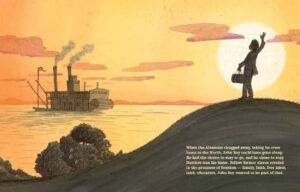

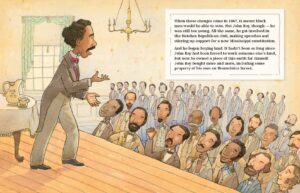

From birth until the age of sixteen John Roy Lynch was a slave. The son of an overseer who died before he could free his family, John Roy began life as a house slave but was sent to the fields when his high-strung mistress made him the brunt of her wrath. Not long after, The Civil War broke out and John Roy bought himself a ride to Natchez and got a job. He started out as a waiter than moved on to pantryman, photographer, and in time orator and even Justice of the Peace. Then, at twenty-four years of age, John Roy Lynch was elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives where he served as Speaker of the House. The year was 1869, and these changes did not pass without incident. Soon an angry white South took its fury out on its African American population and the strides that had been made were rescinded violently. John Roy Lynch would serve out two terms before leaving office. He lived to a ripe old age, dying at last in 1939. A Historical Note, Timeline, Author’s Note, Illustrator’s Note, Bibliography of books “For Further Reading”, and map of John’s journey and the Reconstructed United States circa 1870 appear at the end.

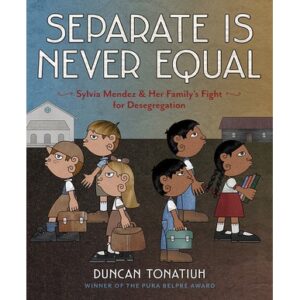

How do you write a book for children about a time when things were starting to look good and then plummeted into bad for a very very long time? I think kids have this perception (oh heck, a bunch of adults too) that we live in the best of all possible worlds. For example, there’s a children’s book series called Infinity Ring where the basic premise is that bad guys have gone and changed history and now it’s up to our heroes to put everything back because, obviously, this world we live in right now is the best. Simple, right? Their first adventure is to make sure Columbus “discovers” America so . . . yup. Too often books for kids reinforce the belief that everything that has happened has to have happened that way. So when we consider how few books really discuss Reconstruction, it’s not exactly surprising. Children’s books are distinguished, in part, by their capacity to inspire hope. What is there about Reconstruction to cause hope at all? And how do you teach that to kids?

How do you write a book for children about a time when things were starting to look good and then plummeted into bad for a very very long time? I think kids have this perception (oh heck, a bunch of adults too) that we live in the best of all possible worlds. For example, there’s a children’s book series called Infinity Ring where the basic premise is that bad guys have gone and changed history and now it’s up to our heroes to put everything back because, obviously, this world we live in right now is the best. Simple, right? Their first adventure is to make sure Columbus “discovers” America so . . . yup. Too often books for kids reinforce the belief that everything that has happened has to have happened that way. So when we consider how few books really discuss Reconstruction, it’s not exactly surprising. Children’s books are distinguished, in part, by their capacity to inspire hope. What is there about Reconstruction to cause hope at all? And how do you teach that to kids?

Barton’s solution is clever because rather than write a book about Reconstruction specifically, he’s found a historical figure that guides the child reader effortlessly through the time period. Lynch’s life is perfect for every step of this process. From slavery to a freedom that felt like slavery. Then slow independence, an education, public speaking, new responsibilities, political success, two Congressional terms, and then an entirely different life after that (serving in the Spanish-American War as a major, moving to Chicago, dying). Barton shows his rise and then follows his election with a two-page spread of KKK mayhem, explaining that the strides made were taken back “In a way, the Civil War wasn’t really over. The battling had not stopped.” And after quoting a speech where Lynch proclaims that America will never be free until “every man, woman, and child can feel and know that his, her, and their rights are fully protected by the strong arm of a generous and grateful Republic,” Barton follows it up with, “If John Roy Lynch had lived a hundred years (and he nearly did), he would not have seen that come to pass.” Barton guides young readers to the brink of the good and then explains the bad, giving context to just how long the worst of it continued. He also leaves it up to them to determine if Lynch’s dream has come to fruition or not (classroom debate time!).

And he plays fair. These days I read nonfiction picture books with my teeth clenched. Why? Because I’ve started holding them to high standards (doggone it). And there are so many moments in this book that could have been done incorrectly. Heck, the first image you see when you open it up is of John Roy Lynch’s family, his white overseer father holding his black wife tenderly as their kids stand by. I saw it and immediately wondered how we could believe that Lynch’s parents ever cared for one another. Yet a turn of the page and Barton not only puts Patrick Lynch’s profession into context (“while he may have loved these slaves, he most likely took the whip to others”) but provides information on how he attempted to buy his wife and children. Later there is some dialogue in the book, as when Lynch’s owner at one point joshes with him at the table and John Roy makes the mistake of offering an honest answer. Yet the dialogue is clearly taken from a text somewhere, not made up to fit the context of the book. I loathe faux dialogue, mostly because it’s entirely unnecessary. Barton shows clearly that one need never rely upon it to make a book exemplary.

And he plays fair. These days I read nonfiction picture books with my teeth clenched. Why? Because I’ve started holding them to high standards (doggone it). And there are so many moments in this book that could have been done incorrectly. Heck, the first image you see when you open it up is of John Roy Lynch’s family, his white overseer father holding his black wife tenderly as their kids stand by. I saw it and immediately wondered how we could believe that Lynch’s parents ever cared for one another. Yet a turn of the page and Barton not only puts Patrick Lynch’s profession into context (“while he may have loved these slaves, he most likely took the whip to others”) but provides information on how he attempted to buy his wife and children. Later there is some dialogue in the book, as when Lynch’s owner at one point joshes with him at the table and John Roy makes the mistake of offering an honest answer. Yet the dialogue is clearly taken from a text somewhere, not made up to fit the context of the book. I loathe faux dialogue, mostly because it’s entirely unnecessary. Barton shows clearly that one need never rely upon it to make a book exemplary.

Finally, you just have to stand in awe of Barton’s storytelling. Not making up dialogue is one thing. Drawing a natural link between a life and the world in which that life lived is another entirely. Take that moment when John Roy answers his master honestly. He’s banished to hard labor on a plantation after his master’s wife gets angry. Then Barton writes, “She was not alone in rage and spite and hurt and lashing out. The leaders of the South reacted the same way to the election of a president – Abraham Lincoln – who was opposed to slavery.” See how he did that? He managed to bring the greater context of the times in line with John Roy’s personal story. Many is the clunky picture book biography that shoehorns in the era or, worse, fails to mention it at all. I much preferred Barton’s methods. There’s an elegance to them.

I’ve been aware of Don Tate for a number of years. No slouch, the guy’s illustrated numerous children’s books, and even wrote (but didn’t illustrate) one that earned him an Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Honor Award (It Jes’ Happened: When Bill Traylor Started to Draw). His is a seemingly simple style. I wouldn’t exactly call it cartoony, but it is kid friendly. Clear lines. Open faces. His watercolors go for honesty and clarity and do not come across as particularly evocative. But I hadn’t ever seen the man do nonfiction, I’ll admit. And while it probably took me a page or two to understand, once I realized why Don Tate was the perfect artist for “John Roy Lynch” it all clicked into place. You see, books about slavery for kids usually follow a prescribed pattern. Some of them go for hyperrealism. Books with art by James Ransome, Eric Velasquez, Floyd Cooper, or E.B Lewis all adhere closely to this style. Then there are the books that are a little more abstract. Books with art by R. Gregory Christie, for example, traipse closely to art worthy of Jacob Lawrence. And Shane W. Evans has a style that’s significantly artistic. A more cartoony style is often considered too simplistic for the heavy subject matter or, worse, disrespectful. But what are we really talking about here? If the book is going to speak honestly about what slavery really was, the subjugation of whole generations of people, then art that hews closely to the truth is going to be too horrific for kids. You need someone who can cushion the blow, to a certain extent. It isn’t that Tate is shying away from the horrors. But when he draws it it loses some of its worst terrors. There is one two-page spread in this book that depicts angry whites whipping and lynching their black neighbors.  It’s not shown as an exact moment in time, but rather a composite of events that would have happened then. And there’s something about Tate’s style that makes it manageable. The whip has not yet fallen and the noose has not yet been placed around a neck, but the angry mobs are there and you know that the worst is imminent. Most interesting to me too is that far in the background a white woman and her two children just stand there, neither approving nor condemning the action. I think you could get a very good conversation out of kids about this family. What are they feeling? Whose side are they on? Why don’t they do something?

It’s not shown as an exact moment in time, but rather a composite of events that would have happened then. And there’s something about Tate’s style that makes it manageable. The whip has not yet fallen and the noose has not yet been placed around a neck, but the angry mobs are there and you know that the worst is imminent. Most interesting to me too is that far in the background a white woman and her two children just stand there, neither approving nor condemning the action. I think you could get a very good conversation out of kids about this family. What are they feeling? Whose side are they on? Why don’t they do something?

And Tate has adapted his style, you can see. Compare the heads and faces in this book to those in one of his earlier books like, Ron’s Big Mission by Rose Blue, in this one he modifies the heads, making them a bit smaller, in proportion with the rest of the body. I was particularly interested in how he did faces as well. If you watch Lynch’s face as a child and teen it’s significant how he keeps is features blank in the presence of white people. Not expressionless, but devoid of telltale thoughts. As a character, the first time he smiles is when he finally has a job he can be paid for. With its silhouetted moments, good design sense, tapered but not muted color palette, and attention to detail, Mr. Tate puts his all into what is by far his most sophisticated work to date.

This year rage erupted over the fact that the Confederate flag continues to fly over the South Carolina statehouse grounds. To imagine that the story Barton relates here does not have immediate applications to contemporary news is facile. As he mentions in his Author’s Note, “I think it’s a shame how little we question why the civil rights movement in this country occurred a full century following the emancipation of the slaves rather than immediately afterward.” So as an author he found an inspiring, if too little known, story of a man who did something absolutely astounding. A story that every schoolchild should know. If there’s any justice in the universe, after reading this book they will. Reconstruction done right. Nonfiction done well.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

- Crow by Barbara Wright

- When Thunder Comes by J. Patrick Lewis

- Hand in Hand: Ten Black Men Who Changed America by Andrea Davis Pinkney

Professional Reviews:

- A star from Publishers Weekly

- Kirkus

Misc: For you, m’dear? An educator’s guide.

Videos: A book trailer and everything!

Thank you, Betsy! Sharp-eyed readers will notice the tiny little “chicken for a dime” in the book trailer. Of all the details that Don captured, that one is my favorite.

I noticed it in the book too! It made me inordinately happy to see.

I am a fan of both Don and Chris’ work. After reading your review and watching the video, The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch has moved to the top of my book list.

Chris Barton is rapidly becoming one of my fave nonfiction people – I want to emulate that know-how with research, and that ease of imparting it in a way that’s just… sitting on the front porch, spinning a yarn – the laden-with-facts bit of it just feels so effortless! And, WOW, Bets, that you noticed that the character had a blank face in the presence of white folk… you have sharp eyes, and Don Tate is a super-sharp artist. Thanks especially for breaking down your thoughts on the artwork. The hyperrealism – I never knew what to call it before, really – is sometimes hard for me to take, much less a child; it’s almost… ugly, in a way. I think this artwork supports a fantastic story of The Reconstruction era, and makes it enticing…

“Enticing” and “The Reconstruction era” in the same sentence is kind of surreal, isn’t it?! Kudos and well done to the author and illustrator!

[…] of books I want to read: The Amazing Age of Judge Roy Lynch by Chris Barton, reviewed at Fuse #8. The Hired Girl by Laura Amy Schlitz, reviewed by Abby the Librarian. 7 Women and the Secret of […]

[…] Elizabeth Bird, librarian extraordinaire, had a lot to say this week about The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch on her School Library Journal blog. […]