new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Alternative Story Structures, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 8 of 8

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Alternative Story Structures in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

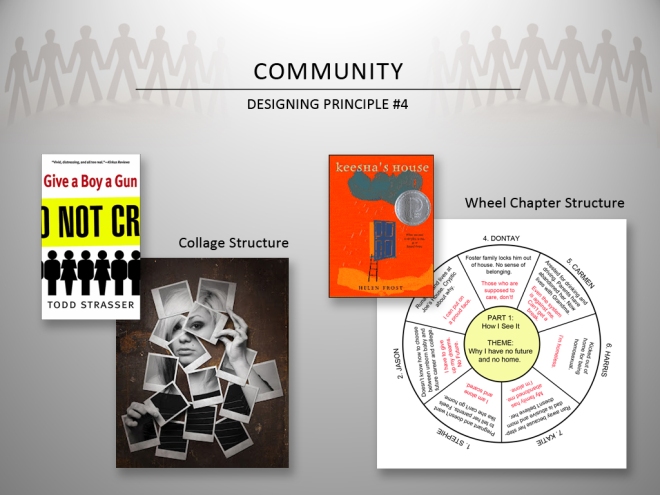

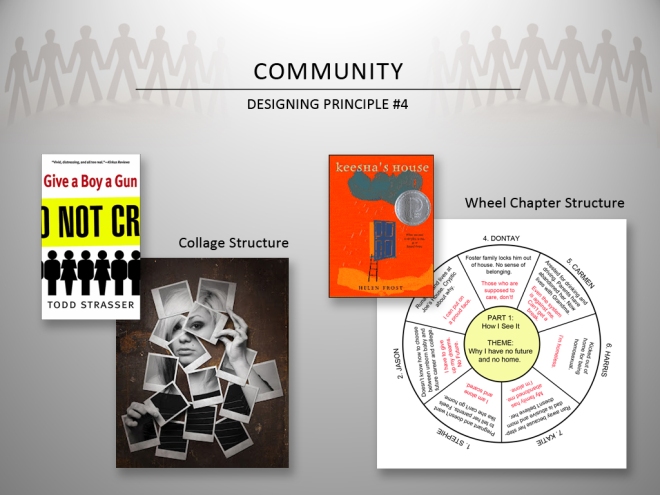

Some stories are not about a single protagonist. Sometimes a group or community becomes the larger focus. Using a community as a designing principle is the fourth category in this series.

Give a Boy a Gun by Todd Struasser explores the complexity of a school shooting and could have been told from POV of the shooter, or a friend of the shooter, or a teacher. Instead Struasser lets an entire community tell this story: friends, parents, teachers, students, etc. In so doing, a portrait of the shooters and the events is constructed by the reader through snippets, interviews, and emails. The structure unveils the fragmentation and chaos of the event itself, and how hard it is to find a single truth of an event or person.

Helen Frost’s verse novel Keesha’s House also creates a portrait of a community, but in a different way. The story follows eight protagonists who become homeless. Each character has his or her own arc, and is given one poem per chapter with which to tell his or her story. Frost’s creates unity between these eight individual stories with the use of a wheel chapter structure. At the core of each chapter is a theme, for example: “Why I can’t live at home,” and each poem of that chapter touches upon the theme in a way that is specific to each character. This structure unites an entire community of abandoned children.

Is your story about a community or ensemble of people? How might you use this to influence the structure of your story?

Up Next: Designing Principle #5 – Parallel Stories and Myth

Want to know more about designing principles? Try these links:

Some stories are not about a single protagonist. Sometimes a group or community becomes the larger focus. Using a community as a designing principle is the fourth category in this series.

Give a Boy a Gun by Todd Struasser explores the complexity of a school shooting and could have been told from POV of the shooter, or a friend of the shooter, or a teacher. Instead Struasser lets an entire community tell this story: friends, parents, teachers, students, etc. In so doing, a portrait of the shooters and the events is constructed by the reader through snippets, interviews, and emails. The structure unveils the fragmentation and chaos of the event itself, and how hard it is to find a single truth of an event or person.

Helen Frost’s verse novel Keesha’s House also creates a portrait of a community, but in a different way. The story follows eight protagonists who become homeless. Each character has his or her own arc, and is given one poem per chapter with which to tell his or her story. Frost’s creates unity between these eight individual stories with the use of a wheel chapter structure. At the core of each chapter is a theme, for example: “Why I can’t live at home,” and each poem of that chapter touches upon the theme in a way that is specific to each character. This structure unites an entire community of abandoned children.

Is your story about a community or ensemble of people? How might you use this to influence the structure of your story?

Up Next: Designing Principle #5 – Parallel Stories and Myth

Want to know more about designing principles? Try these links:

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 7/22/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Story Structure,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Story Structures,

Designing Principle,

Backwards Structure,

Non-Linear Structure,

Time and Design,

Add a tag

We live our lives in a linear progression and that affects the way we think about narrative, how to live our lives, and what we value. Structurally and metaphorically time can be an interesting element to design with. Continuing our discussion on designing principles, lets see how the way we use time can become an organic structural framework.

Backward structures, like the film Memento or Pinter’s play Betrayal become causal mysteries. Charles Ramirez Berg notes that they “draw attention to causal connections, like forward moving structures, but … the narrative fuel is the search for the first cause of known effects.” The play Betrayal begins with a couple’s separation, and as we move back in time, we search for the moment that caused the relationship’s end.

But time can also be chopped up and moved around in any way that serves your story best. In The Time Traveler’s Wife the non-linearity reflects both the premise and unveils the importance of memory to our relationships. In the novel One Day, there’s a linear progression, but each chapter skips forward a year, forcing the reader to fill in the time between. In Groundhog Day and Before I Fall, the protagonists must repeat the same day over and over until they get it right. Even a ticking clock can create a structure; the TV show 24 takes a 24 hour ticking-clock and allots a single episode to each hour.

Does your novel span a day or many years? How does time affect your characters? Is it about looking back, moving forward, or the gaps between? Can the way you slice and dice time reveal another of level of content in your novel and is appropriate for your novel?

Up Next: Designing Principle #4 – Community

Want to know more about designing principles? Try these links:

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 7/22/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Craft,

Story Structure,

Story Design,

Organic Architecture,

Alternative Story Structures,

Designing Principle,

Backwards Structure,

Non-Linear Structure,

Time and Design,

Add a tag

We live our lives in a linear progression and that affects the way we think about narrative, how to live our lives, and what we value. Structurally and metaphorically time can be an interesting element to design with. Continuing our discussion on designing principles, lets see how the way we use time can become an organic structural framework.

Backward structures, like the film Memento or Pinter’s play Betrayal become causal mysteries. Charles Ramirez Berg notes that they “draw attention to causal connections, like forward moving structures, but … the narrative fuel is the search for the first cause of known effects.” The play Betrayal begins with a couple’s separation, and as we move back in time, we search for the moment that caused the relationship’s end.

But time can also be chopped up and moved around in any way that serves your story best. In The Time Traveler’s Wife the non-linearity reflects both the premise and unveils the importance of memory to our relationships. In the novel One Day, there’s a linear progression, but each chapter skips forward a year, forcing the reader to fill in the time between. In Groundhog Day and Before I Fall, the protagonists must repeat the same day over and over until they get it right. Even a ticking clock can create a structure; the TV show 24 takes a 24 hour ticking-clock and allots a single episode to each hour.

Does your novel span a day or many years? How does time affect your characters? Is it about looking back, moving forward, or the gaps between? Can the way you slice and dice time reveal another of level of content in your novel and is appropriate for your novel?

Up Next: Designing Principle #4 – Community

Want to know more about designing principles? Try these links:

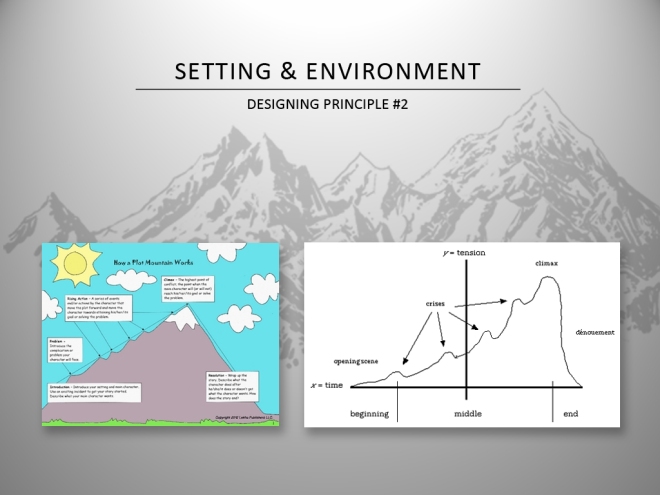

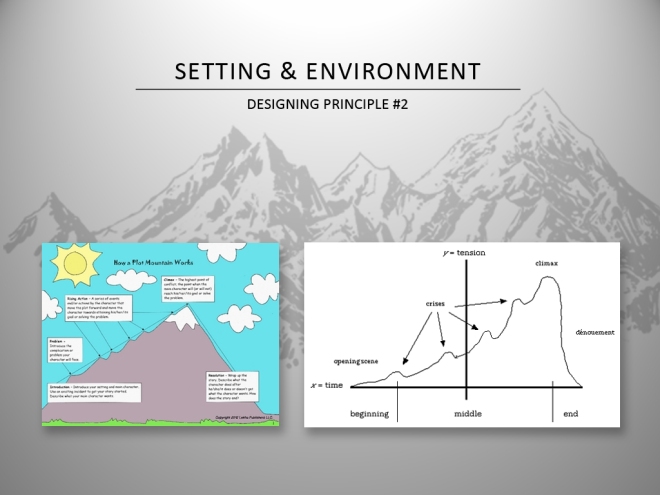

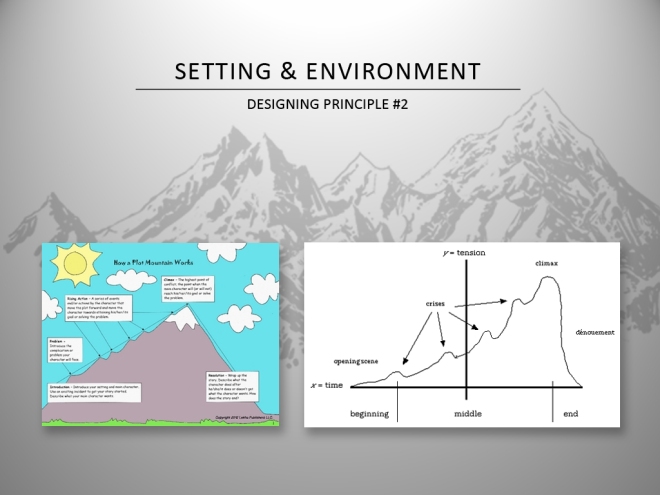

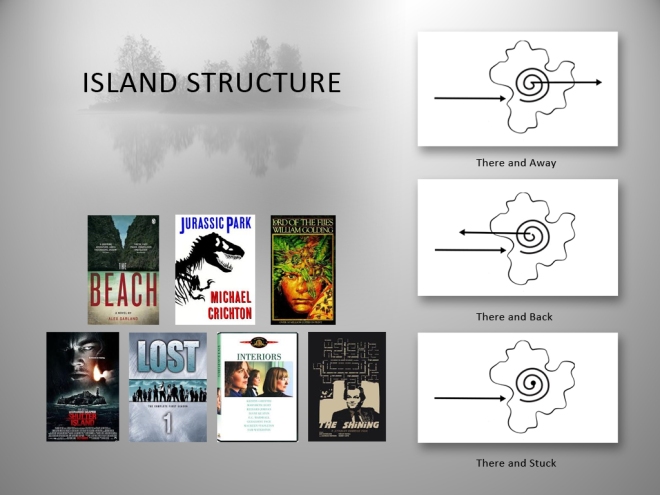

My second category in my series on designing principle is using your setting and environment to as inspiration for your story’s design.

It’s interesting that the predominant structure we talk about is a mountain, which is ultimately a metaphor for a certain kind of movement and escalating energy to a story. In my first post on designing principle I mentioned the river as structure for the Heart of Darkness. Huck Finn is another example of river design and it’s worth noting that both novels have a different rhythm than the mountain structure. They meander more, they’re quieter, they reflect the inherent structure that exists in the novel’s setting.

Let’s consider other environments.

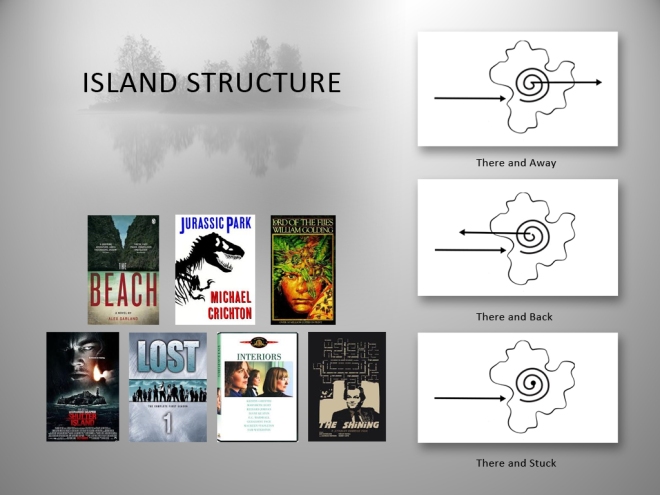

For example: Island Structure.

The initial energy is getting to the island, but once you’ve arrived there is an intense spinning in circles like being lost in a labyrinth. There is a desire to leave the island, but the island won’t let you go. It develops its own rules. In Shutter Island, the island becomes a metaphor for insanity. In Jurassic Park man becomes the rat in a maze of his own experiments. New rules and societies come to exist, as in The Beach, Lord of the Flies, and the TV show Lost. The overall energy is an isolated churning with no way out.

Haunted house stories have a similar structure where the house is the island – or prison – with its own rules, like in The Shining, or The House on Haunted Hill, or even Woody Allen’s dramatic film Interiors where the house is an emotional island isolating its characters.

What about the Ocean?

It has two levels: the surface and the deep. Diving underwater has a different energy than climbing a mountain; the descent becomes increasingly claustrophobic as you get closer to drowning. Whereas the surface is vast and isolating, you can go in any direction, but you must face the wildness of the waves, and the threat of the deep like in Moby Dick and The Perfect Storm.

How about the Forest?

It can be place where you get lost or find magic. In Martine Leavitt’s Keturah and Lord Death the forest becomes an important design element. The forest is death’s realm and the town is the land of the living. The forest’s edge is line upon which Keturah must dance. Initially Keturah is about to die in the forest, but Death gives her a second chance, allowing her to return home. But she’s given tasks and must come back to the forest and revisit Death, creating touch-points in the structure of the story. The story’s rhythm is this undulation between the pull of death and the desire for life.

Think about the environment of your book and ask yourself:

- Does the environment of your book have metaphorical meaning?

- How do your character’s move within it?

- Is it a prison, a path, a portal?

- What natural movement does the environment already provide for your story?

Your story may not be a mountain escalation, but the mountain also provides another good lesson, because you don’t have to be on a mountain to use mountain structure. Look at your environment to see how it might parallel another that you can use an access point to your design.

Up Next: Designing Principle #3 – Time

My second category in my series on designing principle is using your setting and environment to as inspiration for your story’s design.

It’s interesting that the predominant structure we talk about is a mountain, which is ultimately a metaphor for a certain kind of movement and escalating energy to a story. In my first post on designing principle I mentioned the river as structure for the Heart of Darkness. Huck Finn is another example of river design and it’s worth noting that both novels have a different rhythm than the mountain structure. They meander more, they’re quieter, they reflect the inherent structure that exists in the novel’s setting.

Let’s consider other environments.

For example: Island Structure.

The initial energy is getting to the island, but once you’ve arrived there is an intense spinning in circles like being lost in a labyrinth. There is a desire to leave the island, but the island won’t let you go. It develops its own rules. In Shutter Island, the island becomes a metaphor for insanity. In Jurassic Park man becomes the rat in a maze of his own experiments. New rules and societies come to exist, as in The Beach, Lord of the Flies, and the TV show Lost. The overall energy is an isolated churning with no way out.

Haunted house stories have a similar structure where the house is the island – or prison – with its own rules, like in The Shining, or The House on Haunted Hill, or even Woody Allen’s dramatic film Interiors where the house is an emotional island isolating its characters.

What about the Ocean?

It has two levels: the surface and the deep. Diving underwater has a different energy than climbing a mountain; the descent becomes increasingly claustrophobic as you get closer to drowning. Whereas the surface is vast and isolating, you can go in any direction, but you must face the wildness of the waves, and the threat of the deep like in Moby Dick and The Perfect Storm.

How about the Forest?

It can be place where you get lost or find magic. In Martine Leavitt’s Keturah and Lord Death the forest becomes an important design element. The forest is death’s realm and the town is the land of the living. The forest’s edge is line upon which Keturah must dance. Initially Keturah is about to die in the forest, but Death gives her a second chance, allowing her to return home. But she’s given tasks and must come back to the forest and revisit Death, creating touch-points in the structure of the story. The story’s rhythm is this undulation between the pull of death and the desire for life.

Think about the environment of your book and ask yourself:

- Does the environment of your book have metaphorical meaning?

- How do your character’s move within it?

- Is it a prison, a path, a portal?

- What natural movement does the environment already provide for your story?

Your story may not be a mountain escalation, but the mountain also provides another good lesson, because you don’t have to be on a mountain to use mountain structure. Look at your environment to see how it might parallel another that you can use an access point to your design.

Up Next: Designing Principle #3 – Time

In my last post we began our survey of alternative story structures. That post covered non-linear structure, episodic structure with an arc, wheel structure, and meandering structure.

Today we’ll continue to push past the traditional story structure idea of a mountain or triangle shape to consider branching structure, spiral structure, multiple POV structure, parallell structure, and cumulative structure!

Again, you could apply these structural ideas to a traditional mountain shape, or let them create their own rhythm and energy.

BRANCHING STRUCTURE

This structure consists of “a system of paths that extend from a few central points by splitting and adding smaller and smaller parts … Each branch usually represents a complete society in detail or a detailed stage of the same society that the hero explores” (Truby). This is a popular structure used in non-fiction books.

- Film Examples: It’s a Wonderful Life, Nashville, Traffic.

- Book Examples: Gulliver’s Travels (Swift), Phineus Gage: A Gruesome but True Story about Brain Science (Fleishman).

SPIRAL STRUCTURE

Spiral structure “is a path that circles inward to the center…[wherein] a character keeps returning to a single event or memory and explores it at progressively deeper levels” (Truby).

- Film Examples: Vertigo, The Conversation, Memento.

- Book Examples: Before I Fall (Oliver), How to Tell a True War Story (O’Brien).

MULTIPLE POINT-OF-VIEW STRUCTURE

This structure has multiple protagonists and provides the point-of-view (POV) of multiple characters. Variations include one character telling his/her whole story and then another character telling a different version of the story. Another popular style is alternating viewpoints (chapter-by-chapter) as the story progresses. In film, multiple POV can sometimes be accompanied by a split-screen technique.

- Film Examples: He Loves Me…He Loves Me Not, Rules of Attraction, Sliding Doors.

- Book Examples: Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist (Cohn & Levithan), The Scorpio Races (Stiefvater), Jumped (Williams-Garcia), Skud (Foon), Keesha’s House (Frost), Blink & Caution (Wynne-Jones), Tangled (Mackler).

PARALLEL STRUCTURE

(Also known as: Parallel Substitution Structure, Multiple Personality Structure)

This structure has dual or multiple storylines that mirror and reflect each other. Stories can include different protagonists or a single protagonist in different “lives.” Storylines often exist within separate time frames, dimensions, or locations. In the instance of parallel substitution structure, actual events in a protagonist’s storyline are substituted with thematic stories such as fables, religious stories, myth, or a parallel thematic scene. The reader is meant to make the thematic and causal connections through the substitution. In the case of multiple personality structure, “multiple protagonists are the same person, or different versions of the same person” (Berg). Multiple personality structure can also be considered a variant of multiple POV or branching structure.

- Film Examples: The Fountain, Sliding Doors, Identity, Fight Club.

- Book Examples: The Powerbook (Winterson), Habibi (Thompson), American Born Chinese (Yang), Revolution (Donnelly).

CUMULATIVE STRUCTURE

This structure is most often used in picture books and songs. It builds a story through a “repetitive pattern or text structure: each page repeats the text from the previous page, adding a new line/plot element. As the details pile up, the tale builds to a climax” (Carver).

- Book Examples: There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly (Mills), This is the House that Jack Built (Mother Goose).

Do you know of any other alternative story structures? I’d love to hear all about them!

Up next: Designing principals and how to make decisions on what the best plot type and story structure is best for your project!

Works Cited:

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

In my last post we began our survey of alternative story structures. That post covered non-linear structure, episodic structure with an arc, wheel structure, and meandering structure.

Today we’ll continue to push past the traditional story structure idea of a mountain or triangle shape to consider branching structure, spiral structure, multiple POV structure, parallell structure, and cumulative structure!

Again, you could apply these structural ideas to a traditional mountain shape, or let them create their own rhythm and energy.

BRANCHING STRUCTURE

This structure consists of “a system of paths that extend from a few central points by splitting and adding smaller and smaller parts … Each branch usually represents a complete society in detail or a detailed stage of the same society that the hero explores” (Truby). This is a popular structure used in non-fiction books.

- Film Examples: It’s a Wonderful Life, Nashville, Traffic.

- Book Examples: Gulliver’s Travels (Swift), Phineus Gage: A Gruesome but True Story about Brain Science (Fleishman).

SPIRAL STRUCTURE

Spiral structure “is a path that circles inward to the center…[wherein] a character keeps returning to a single event or memory and explores it at progressively deeper levels” (Truby).

- Film Examples: Vertigo, The Conversation, Memento.

- Book Examples: Before I Fall (Oliver), How to Tell a True War Story (O’Brien).

MULTIPLE POINT-OF-VIEW STRUCTURE

This structure has multiple protagonists and provides the point-of-view (POV) of multiple characters. Variations include one character telling his/her whole story and then another character telling a different version of the story. Another popular style is alternating viewpoints (chapter-by-chapter) as the story progresses. In film, multiple POV can sometimes be accompanied by a split-screen technique.

- Film Examples: He Loves Me…He Loves Me Not, Rules of Attraction, Sliding Doors.

- Book Examples: Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist (Cohn & Levithan), The Scorpio Races (Stiefvater), Jumped (Williams-Garcia), Skud (Foon), Keesha’s House (Frost), Blink & Caution (Wynne-Jones), Tangled (Mackler).

PARALLEL STRUCTURE

(Also known as: Parallel Substitution Structure, Multiple Personality Structure)

This structure has dual or multiple storylines that mirror and reflect each other. Stories can include different protagonists or a single protagonist in different “lives.” Storylines often exist within separate time frames, dimensions, or locations. In the instance of parallel substitution structure, actual events in a protagonist’s storyline are substituted with thematic stories such as fables, religious stories, myth, or a parallel thematic scene. The reader is meant to make the thematic and causal connections through the substitution. In the case of multiple personality structure, “multiple protagonists are the same person, or different versions of the same person” (Berg). Multiple personality structure can also be considered a variant of multiple POV or branching structure.

- Film Examples: The Fountain, Sliding Doors, Identity, Fight Club.

- Book Examples: The Powerbook (Winterson), Habibi (Thompson), American Born Chinese (Yang), Revolution (Donnelly).

CUMULATIVE STRUCTURE

This structure is most often used in picture books and songs. It builds a story through a “repetitive pattern or text structure: each page repeats the text from the previous page, adding a new line/plot element. As the details pile up, the tale builds to a climax” (Carver).

- Book Examples: There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly (Mills), This is the House that Jack Built (Mother Goose).

Do you know of any other alternative story structures? I’d love to hear all about them!

Up next: Designing principals and how to make decisions on what the best plot type and story structure is best for your project!

Works Cited:

Berg, Charles Ramirez. “A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying the ‘Tarantino Effect.’” Film Criticism, Vol. 31, Issue 1-2, 5-57, 22 Sept 2006. Ebsco Host. Web. 6 May 2011.

Carver, Renee. “Cumulative Tales Primary Lesson Plan.” Primary School. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 31 Aug 2012.

Truby, John. The Anatomy of Story: 22 Steps to Becoming a Master Story- teller. New York: Faber and Faber Inc., 2007.

I also think of Val Howlett’s short story, “The Arf thing,” told from the perspective of several characters about one event (http://lunchticket.org/the-arf-thing/) and The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver. The novel I’m working on is probably more of an ensemble piece. I’m telling it from the perspectives of three characters, but I think it’s a little different from what you discuss here. Yet I’d like to try an ensemble piece about one pivotal event.