Energy consumption is changing. Governments and businesses around the world are exploring low carbon options including biofuels, natural gas and wind in an attempt to achieve longstanding energy security. Production of new sources has led to controversies about economic and environmental impacts and the trade-offs they generate between food and fuel production, energy security and environmental quality.

The post How much do you know about sources of energy? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Migrant farmworkers plant and pick most of the fruits and vegetables that you eat. Seasonal crop farmers, who employ workers only a few weeks of the year, rely on workers who migrate from one job to another. However, farmers’ ability to rely on migrants to fill their seasonal labor needs is in danger. From 1989 through 1988, roughly half of all seasonal crop farmworkers migrated: traveled at least 75 miles for a U.S. job. Since then, the share of workers who migrate has dropped by more than in half, hitting 18% in 2012.

The post Are migrant farm workers disappearing? appeared first on OUPblog.

By Fuhai Hong and Xiaojian Zhao

“In an irony heaped on an irony, Anthony Watts is lying and exaggerating about a research paper on exaggeration and information manipulation – to stoke the conspiracy theory that climate science is a hoax.” –Sou (HotWhopper) in response to Anthony Watts on WUWT

How do individuals manipulate the information they privately have in strategic interactions? The economics of information is a classic topic, and mass media often features in its analysis. Indeed, the international mass media play an important role in forming people’s perception of the climate problem. However, media coverage on the climate problem is often biased.

Media reporting our paper are vivid examples of the prevalence and variety of media bias in reporting scientific results. While our analysis investigates the media tendency of accentuating or even exaggerating scientific findings of climate damage, the articles misinterpret our results, accentuate and exaggerate one side of our research, and completely omit the other side.

In our research, we analysed why and how a media bias accentuating or even exaggerating climate damage emerges, and how it influences nations’ negotiating an International Environmental Agreement (IEA). We set up a game theoretic model which involves an international mass medium with information advantage, many homogenous countries, and an IEA as players in the game. We then solve for its equilibrium, which, in plain English, means that every player in the game is maximizing her payoff given what others do. The players may update their beliefs in a reasonable way (by Bayes’ rule in our jargon) if they are uncertain about the true state of nature on climate damage. In our model, media bias emerged as an equilibrium outcome, suppressing information the mass media held privately.

The climate problem is important because it involves possibilities of catastrophes and long-lasting systemic effects. The main difficulty of the climate problem is that it is a global public problem and we lack an international government to regulate it. Strong incentives not to contribute and benefit from others’ efforts (free ride) lead to a serious under-participation in an IEA, which further makes the IEA mechanism unlikely to provide enough public goods. The current impasse of climate negotiations showcases this difficulty. The media bias we focused on might have an ex post “instrumental” value as the over-pessimism from the media bias may alleviate the under-participation problem to some extent. However, the media bias could also be detrimental, due to the issue of credibility (as people can update their beliefs). As a result, the welfare implication is ambiguous.

Why certain media have incentives to engage in biased coverage does not mean “justifying lying about climate change.”

Media skeptical of anthropogenic climate changes claimed that our paper advocated lying about climate change, and they used this claim to attack the low carbon movement. Townhall magazine published an article entitled “Academics `Prove’ It’s Okay To Lie About Climate Change” right after our accepted paper was made available online. Further attacks came in; the main tones remained the same. Neglecting the fact that our analysis focuses on media bias, many of the media seemed to tactically avoid discussing media bias (because they knew that they were very biased?), and focused on attacking scientific research on climate change, as if this was the topic of our paper. They often misinterpret the notions “ex ante” and “ex post” (e.g. Motl), believing it to reflect when countries join the IEA in our model, rather than the timing in which we assess the information manipulation. Our conjecture is that most of these media reporting our paper did not actually read through our paper.

As our simple model cannot capture all directions and aspects of media bias on the climate issue, especially those showing up in the coverage of our paper, we call for further scientific research on media bias in reporting scientific results. Furthermore, while the economics profession has the common sense that the global public nature and its associated free-riding incentives are the main difficulty of the climate problem, we find that the media coverage on the climate problem significantly lacks attention to these issues.

Finally, consider the end of an article in the Economist magazine, in which the author concludes that “In some cases, scientists who work on climate-change issues, and those who put together the IPCC report, must be truly exasperated to have watched the media first exaggerate aspects of their report, and then accuse the IPCC of responsibility for the media’s exaggerations.”

Fuhai Hong is an assistant professor in the Division of Economics, Nanyang Technological University. Xiaojian Zhao is an assistant professor in the Department of Economics, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Together, they are the authors of “Information Manipulation and Climate Agreements” (available to read for free for a limited time) in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics.

The American Journal of Agricultural Economics provides a forum for creative and scholarly work on the economics of agriculture and food, natural resources and the environment, and rural and community development throughout the world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: climate change headlines background in sepia. © belterz via iStockphoto.

The post Media bias and the climate issue appeared first on OUPblog.

By Hope Michelson

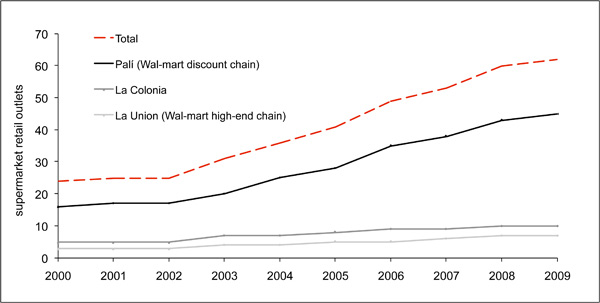

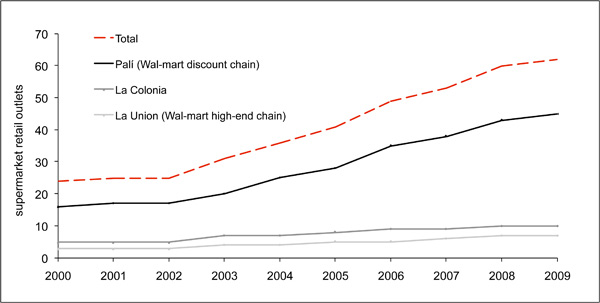

Walmart now has stores in more than fifteen developing countries in Central and South America, Asia and Africa. A glimpse at the scale of operations: Nicaragua, with a population of approximately six million, currently has 78 Walmart retail outlets with more on the way. That’s one store for every 75,000 Nicaraguans; in the United States there’s a Walmart store for every 69,000 people. The growth has been rapid; in the last seven years, the corporation has more than doubled the number of stores in Nicaragua (see accompanying graphs — Figure 1 from the paper).

When a supermarket chain like Walmart moves into a developing country it requires a steady supply of fresh fruits and vegetables largely sourced domestically. In developing countries where the majority of the poor rely on agriculture for their livelihood, this means that poor farmers are increasingly selling produce to and contracting directly with large corporations. In precisely this way, Walmart has begun to transform the domestic agricultural markets in Nicaragua over the past decade. This profound change has been met with both excitement and trepidation by governments and development organizations because the likely effects on poverty and inequality are not known, in particular:

- What existing assets or experience are required for a farmer to sell their produce to supermarkets?

- Do small farmers who sell their produce to supermarkets benefit from the relationship?

- What is the role of NGOs in facilitating small farmer relationships with supermarkets?

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets.

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets.

Generally, researchers have studied the inclusion of farmers in supply chains by measuring the income, assets and welfare of a group of farmers selling a crop to supermarkets (“suppliers”) with a similar group of farmers selling the same crop in traditional markets (“non-suppliers”). This research has provided important insights but has struggled with two persistent challenges.

First, because most existing studies rely on surveys of farmers living in the same area, we do not know how important farmer experience or assets such as farm machinery or irrigation, are for inclusion in supply chains in comparison to other farmer characteristics like community access to water or proximity to good roads.

Second, without measurements on supplier and non-supplier farmers over time it is difficult for a researcher to isolate the effect being a supplier has on the farmer. For example, if Walmart excels at choosing higher-ability farmers as suppliers, a study that just compared supplier and non-supplier incomes would overestimate the supermarket effect because Walmart’s high-ability farmers would earn more income even if they had not contracted with the supermarket.

With these two challenges in mind, I implemented a research project in Nicaragua in which I first identified all small farmers who had had a steady supply relationship with supermarkets for at least one year since 2000 (see accompanying graphs — Figure 2 from the paper). I also revisited 400 farmers not supplying supermarkets but living in areas where supermarkets were buying produce. My team and I surveyed farmers about their experiences over the past eight years: the markets where they had sold, the farming, land, and household assets they had owned. Since my study included farmers selling a variety of crops to supermarkets and measured how their assets, and supermarket relationships, changed in time, I was able to more rigorously address how these markets affected small farmers. The project was part of a collaboration between researchers Michigan State University, Cornell University, and the Nitlapan Institute in Managua.

Results

Farmer participation

Farmers located close to the primary road network and Nicaragua’s capital, Managua, where the major sorting and packing facility is located, and with conditions that allow them to farm year round were much more likely to be suppliers. Remarkably, this effect was much stronger than other farmer characteristics such as existing farm capital or experience.

Farmer welfare

Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.

Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.

One way to think of income is as a flow of financial resources based, in part, on a farmer’s assets. By statistically relating a change in assets to a change in income I find that a 16% increase in assets corresponds to an average increase in annual household income of about $200 — or 15% of the average 2007 income for the farmers I studied.

Our previous work discovered that supermarkets don’t pay farmers a higher mean price than traditional markets but they do offer a more stable price. This analysis suggests a reason that household assets – and thus income — increase among farmers who sell to supermarkets; shielded from price fluctuations in the traditional markets by the supermarket contract, farmers invest in agriculture, in some cases moving to year-round cultivation. Farmers finance these investments through higher and more stable incomes and new credit sources. Income increases are attributable not to higher average prices but likely to increased production quantities.

NGOs

NGOs have played an important role in small farmer access to supermarket supply chains all over the world. In Nicaragua, a USAID program funded NGOs to help small farmers sell to supermarkets. These NGOs established farmers’ cooperatives and provided technical assistance, contract negotiation, and financing. Do NGOs change farmer selection or outcomes? Do they choose farmers with less wealth or experience? Or do farmers working with NGOs benefit in a special way from supermarkets because of the services NGOs provide?

We find, on average, that NGO-assisted farmers start with similar productive assets and land as those who sell to supermarkets without NGO assistance. Nor do we find a special effect on the assets of NGO-assisted farmers. However, we do find that NGOs play a critical role in keeping farmers with little previous experience in vegetable production in the supply chain. Low-experience farmers who are not assisted by NGOs are more likely to drop out of the supply chain than those assisted by NGOs.

Conclusions

These findings offer grounds for optimism and also a measure of caution with respect to the effects of supermarkets operating in developing countries. Supermarket contracts improve farmer welfare, and the improvements are detectable in farmers’ assets. However, since being close to roads and having the ability to farm year round is so critical to inclusion in the supply chain, not all farmers will be afforded these opportunities. Moreover, because these trends are still nascent in Nicaragua and in many other parts of the developing world, it remains to be seen what the broader effects will be for the agricultural sector and development. For example, as NGOs invest in preparing more small farmers to supply supermarkets, the gains to farmers from joining supply chains may be lost to increased competition. Our results in Nicaragua suggest that, given the small number of supplier farmers, changes in rural poverty related to supermarket expansion will be modest, but how will these supply chains, and the benefits they represent for farmers, change over time? I am currently a part of a team studying Walmart supply chains in China, which will interrogate these questions on a much larger scale in the context of a global and rapidly expanding economy.

Hope Michelson is a postdoctoral fellow at Columbia University’s Earth Institute in the Tropical Agriculture and Rural Environment program. She completed her doctoral research in the Economics of Development in 2010 at Cornell University’s Department of Applied Economics. She is the author of “Small Farmers, NGOs, and a Walmart World: Welfare Effects of Supermarkets Operating in Nicaragua” in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, which is available to read for free for a limited time.

The American Journal of Agricultural Economics provides a forum for creative and scholarly work on the economics of agriculture and food, natural resources and the environment, and rural and community development throughout the world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: All images property of Hope Michelson. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post What happens when Walmart comes to Nicaragua? appeared first on OUPblog.

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets.

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets. Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.

Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.