new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Canadian picture books, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Canadian picture books in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 8/24/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Canadian picture books,

picture book readalouds,

2016 picture books,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 picture book readalouds,

Reviews,

picture books,

Canadian children's books,

Tundra Books,

Bill Slavin,

Add a tag

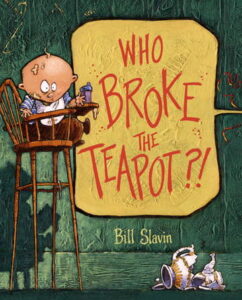

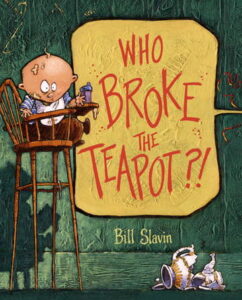

Who Broke the Teapot?!

Who Broke the Teapot?!

By Bill Slavin

Tundra Books

$16.99

ISBN: 978-1-77049-833-4

Ages 3-5

On shelves now

In the average life of a child, whodunits are the stuff of life itself. Who took the last cookie? Who used up all the milk and then didn’t put it on the shopping list? Who removed ALL the rolls of toilet paper that I SPECIFICALLY remember buying at the store on Sunday and now seem to have vanished into some toilet paper eating inter-dimension? The larger the family, the great the number of suspects. But picture books that could be called whodunits run a risk of actually going out and teaching something. A lesson about honesty or owning up to your own mistakes. Blech. I’ll have none of it. Hand me that copy of Bill Slavin’s Who Broke the Teapot?! instead, please. Instead of morals and sanctity I’ll take madcap romps, flashbacks, and the occasional livid cat. Loads of fun to read aloud, surprisingly beautiful to the eye, and with a twist that no one will see coming, Who Broke the Teapot?! has it all, baby. Intact teapot not included.

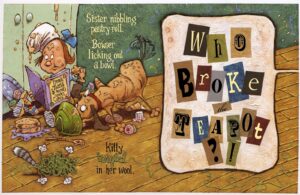

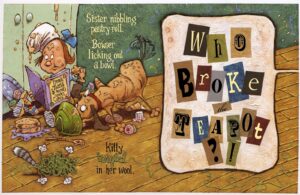

The scene of the crime: The kitchen. The family? Oblivious. As the mother enters the room it’s just your average morning. There’s a baby in a high chair, a brother attached to a ceiling fan by his suspenders, a dad still in his underwear reading the paper, a daughter eating pastries, a dog aiding her in this endeavor, and a cat so tangled up in wool that it’s a wonder you can still make out its paws. And yet in the doorway, far from the madding crowd, sits a lone, broken, teapot. Everyone proclaims innocence. Everyone seems trustworthy in that respect. Indeed, the only person to claim responsibility is the baby (to whom the mother tosses a dismissive, “I doubt it”). Now take a trip back in time just five minutes and all is revealed. The true culprit? You’ll have to read the book yourself. You final parting shot is the mother accepting a teapot stuck together with scotch tape and love from her affectionate offspring.

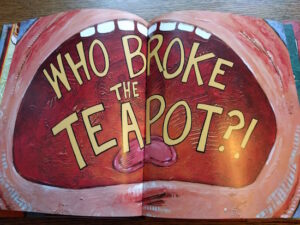

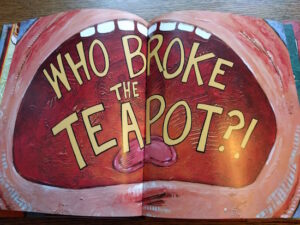

Generally when I write a picture book review I have a pretty standard format that I adhere to. I start with an opening paragraph (done), move on to a description of the plot in the next paragraph (so far, so good), and in the third paragraph I talk about some aspect of the writing. It could be the overall theme or the writing or the plotting. After that I talk about the art. This pattern is almost never mucked with . . . until today!! Because ladies and gents, you have just GOT to take a gander at what Mr. Slavin’s doing here with his acrylics. Glancing at the art isn’t going to do it. You have to pick this book up and really inspect the art. For the bulk of it the human characters are your usual cartoony folks. Very smooth paints. But even the most cursory glance at the backgrounds yields rewards. The walls are textured with thick, luscious paints adhering to different patterns. There’s even a touch of mixed media to the old affair, what with cat’s yarn being real thread and all (note too how Slavin seamlessly makes it look as if the yarn is wrapped around the legs of the high chair). Then the typography starts to get involved. The second time the mom says “Who broke the teapot?!” the words look like the disparate letters of a rushed ransom note. As emotions heat up (really just the emotions of the mom, to be honest) the thick paints crunch when she says “CRUNCHED”, acquire zigzags as her temper unfurls, and eventually belie the smoothness of the characters’ skin when the texture invades the inside of the two-page spread of the now screaming mother’s mouth.

Generally when I write a picture book review I have a pretty standard format that I adhere to. I start with an opening paragraph (done), move on to a description of the plot in the next paragraph (so far, so good), and in the third paragraph I talk about some aspect of the writing. It could be the overall theme or the writing or the plotting. After that I talk about the art. This pattern is almost never mucked with . . . until today!! Because ladies and gents, you have just GOT to take a gander at what Mr. Slavin’s doing here with his acrylics. Glancing at the art isn’t going to do it. You have to pick this book up and really inspect the art. For the bulk of it the human characters are your usual cartoony folks. Very smooth paints. But even the most cursory glance at the backgrounds yields rewards. The walls are textured with thick, luscious paints adhering to different patterns. There’s even a touch of mixed media to the old affair, what with cat’s yarn being real thread and all (note too how Slavin seamlessly makes it look as if the yarn is wrapped around the legs of the high chair). Then the typography starts to get involved. The second time the mom says “Who broke the teapot?!” the words look like the disparate letters of a rushed ransom note. As emotions heat up (really just the emotions of the mom, to be honest) the thick paints crunch when she says “CRUNCHED”, acquire zigzags as her temper unfurls, and eventually belie the smoothness of the characters’ skin when the texture invades the inside of the two-page spread of the now screaming mother’s mouth.

So, good textures. But let us not forget in all this just how important the colors of those thick paints are as well. Watching them shift from one mood to another is akin to standing beneath the Northern Lights. You could be forgiven for not noticing the first, second, third, or even fourth time you read the book. Yet these color changes are imperative to the storytelling. As emotions heat up or the action on the page ramps up, the cool blues and greens ignite into hot reds, yellows, and oranges. Taken as a whole the book is a rainbow of different backgrounds, until at long last everything subsides a little and becomes a chipper cool blue.

Now kids love a good mystery, and I’m not talking just the 9 and 10-year-olds. Virtually every single age of childhood has a weakness for books that set up mysterious circumstances and then reveal all with a flourish. Heck, why do you think babies like the game of peekaboo? Think of it as the ultimate example of mystery and payoff. Picture book mysteries are, however, far more difficult to write than, say, an episode of Nate the Great. You have to center the book squarely in the child’s universe, give them all the clues, and then make clear to the reader what actually happened. To do this you can show the perpetrator of the crime committing the foul deed at the start of the book or you can spot clues throughout the story pointing clearly to the miscreant. In the case of Who Broke the Teapot, Slavin teaches (in his own way) that old Sherlock Holmes phrase, “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

Now kids love a good mystery, and I’m not talking just the 9 and 10-year-olds. Virtually every single age of childhood has a weakness for books that set up mysterious circumstances and then reveal all with a flourish. Heck, why do you think babies like the game of peekaboo? Think of it as the ultimate example of mystery and payoff. Picture book mysteries are, however, far more difficult to write than, say, an episode of Nate the Great. You have to center the book squarely in the child’s universe, give them all the clues, and then make clear to the reader what actually happened. To do this you can show the perpetrator of the crime committing the foul deed at the start of the book or you can spot clues throughout the story pointing clearly to the miscreant. In the case of Who Broke the Teapot, Slavin teaches (in his own way) that old Sherlock Holmes phrase, “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

I love it when a book turns everything around at the end and asks the reader to think long and hard about what they’ve just seen. Remember the end of The Cat in the Hat when everything’s been cleaned up just in time and the mother comes in asking the kids what they got up to while she was gone? The book ends with a canny, “Well, what would YOU do if your mother asked YOU?” Who Broke the Teapot?! does something similar at its end as well. The facts have been laid before the readers. The baby has claimed responsibility and maybe he is to blame after all. But wasn’t the mother just as responsible? It would be very interesting indeed to poll a classroom of Kindergartners to see where they ascribe the bulk of the blame. It may even say something about a kid if they side with the baby more or the mommy more.

I also love that the flashback does far more than explain who broke the teapot. It explains why exactly most of the members of this family are dwelling in a kind of generally accepted chaotic stew. You take it for granted when you first start reading. A kid’s hanging from a ceiling fan? Sure. Yeah. That happens. But the explanation, when it comes, belies that initial response. The parents don’t question his position so you don’t question it. That is your first mistake. Never take your lead from parents. And speaking of the flashback, let’s just stand aside for a moment and remember just how sophisticated it is to portray this concept in a picture book at all. You’re asking a child audience to accept that there is a “before” to every book they read. Few titles go back in time to explain how we got to where we are now. Slavin’s does so easily, and it will be the rare reader that can’t follow him on this trip back into the past.

I also love that the flashback does far more than explain who broke the teapot. It explains why exactly most of the members of this family are dwelling in a kind of generally accepted chaotic stew. You take it for granted when you first start reading. A kid’s hanging from a ceiling fan? Sure. Yeah. That happens. But the explanation, when it comes, belies that initial response. The parents don’t question his position so you don’t question it. That is your first mistake. Never take your lead from parents. And speaking of the flashback, let’s just stand aside for a moment and remember just how sophisticated it is to portray this concept in a picture book at all. You’re asking a child audience to accept that there is a “before” to every book they read. Few titles go back in time to explain how we got to where we are now. Slavin’s does so easily, and it will be the rare reader that can’t follow him on this trip back into the past.

I think the only real mystery here is why this book isn’t better known. And its only crime is that it’s Canadian, and therefore can’t win any of the big American awards here in the States. It’s also too amusing for awards. Until we get ourselves an official humor award for children’s books, titles like Who Broke the Teapot?! are doomed to fly under the radar. That’s okay. This is going to be the kind of book that children remember for decades. They’re going to be the ones walking into their public libraries asking the children’s librarians on the desks to bring to them an obscure picture book from their youth. “There was a thing that was broken . . . like a china plate or something . . . and there was this cat tied up in string?” You have my sympathies, children’s librarians of the future. In the meantime, better enjoy the book now. Whether it’s read to a large group or one-on-one, this puppy packs a powerful punch.

On shelves now

Source: Publisher sent final copy for review.

Like This? Then Try:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 2/14/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

issue picture books,

Julie Pearson,

Pajama Press,

translated picture books,

Reviews,

Canadian children's books,

Canadian picture books,

Manon Gauthier,

international children's books,

diverse picture books,

2016 picture books,

Reviews 2016,

Add a tag

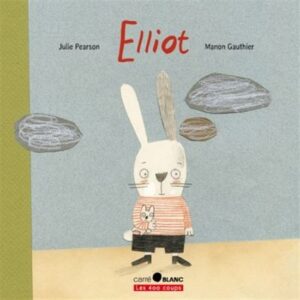

Elliot

Elliot

By Julie Pearson

Translated by Erin Woods

Illustrated by Manon Gauthier

Pajama Press

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1-927485-85-9

Ages 4-7

On shelves April 4th

The librarian and the bookseller face shelving challenges the like of which you wouldn’t believe. You think all picture books should simply be shelved in the picture book section by the author’s last name and that’s the end of it? Think again. If picture books served a single, solitary purpose that might well be the case. But picture books carry heavy burdens, far above and beyond their usual literacy needs. People use picture books for all sorts of reasons. There are picture books for high school graduates, for people to read aloud during wedding ceremonies, for funerals, and as wry adult jokes. On the children’s side, picture books can help parents and children navigate difficult subjects and topics. From potty training to racism, complicated historical moments and new ways of seeing the world, the picture book has proved to be an infinitely flexible object. The one purpose that is too little discussed but is its most complicated and complex use is when it needs to explain the inexplicable. Cancer. Absentee parents. Down syndrome. Explaining just one of these issues at a time is hard. Explaining two at one time? I’d say it was almost impossible. Julie Pearson’s book Elliot takes on that burden, attempting to explain both the foster system and children with emotional developmental difficulties at the same time. It works in some ways, and it doesn’t work in others, but when it comes to the attempt itself it is, quite possibly, heroic.

Elliot has a loving mother and father, that much we know. However, for whatever reason, Elliot’s parents have difficulty with their young son. When he cries, or yells, or misbehaves they have no idea how to handle these situations. So the social worker Thomas is called in and right away he sets up Elliot in a foster home. There, people understand Elliot’s needs. He goes home with his parents, after they learn how to take care of him, but fairly soon the trouble starts up again. This time Thomas takes Elliot to a new foster care home, and again he’s well tended. So much so that even though he loves his parents, he worries about going home with them. However, in time Thomas assures Elliot that his parents will never take care of him again. And then Thomas finds Elliot a ‘forever” home full of people who love AND understand how to take care of him. One he never has to leave.

Let me say right here and now that this is the first picture book about the foster care system, in any form, that I have encountered. Middle grade fiction will occasionally touch on the issue, though rarely in any depth. Yet in spite of the fact that thousands and thousands of children go through the foster care system, books for them are nonexistent. Even “Elliot” is specific to only one kind of foster care situation (children with developmental issues). For children with parents who are out of the picture for other reasons, they may take some comfort in this book, but it’s pretty specific to its own situation. Pearson writes from a place of experience, and she’s writing for a very young audience, hence the comforting format of repetition (whether we’re seeing Elliot’s same problems over and over again, or the situation of entering one foster care home after another). Pearson tries to go for the Rule of Three, having Elliot stay with three different foster care families (the third being the family he ends up with). From a literary standpoint I understand why this was done, and I can see how it reflects an authentic experience, but it does seem strange to young readers. Because the families are never named, their only distinguishing characteristics appear to be the number of children in the families and the family pets. Otherwise they blur.

Let me say right here and now that this is the first picture book about the foster care system, in any form, that I have encountered. Middle grade fiction will occasionally touch on the issue, though rarely in any depth. Yet in spite of the fact that thousands and thousands of children go through the foster care system, books for them are nonexistent. Even “Elliot” is specific to only one kind of foster care situation (children with developmental issues). For children with parents who are out of the picture for other reasons, they may take some comfort in this book, but it’s pretty specific to its own situation. Pearson writes from a place of experience, and she’s writing for a very young audience, hence the comforting format of repetition (whether we’re seeing Elliot’s same problems over and over again, or the situation of entering one foster care home after another). Pearson tries to go for the Rule of Three, having Elliot stay with three different foster care families (the third being the family he ends up with). From a literary standpoint I understand why this was done, and I can see how it reflects an authentic experience, but it does seem strange to young readers. Because the families are never named, their only distinguishing characteristics appear to be the number of children in the families and the family pets. Otherwise they blur.

Pearson is attempting to make this accessible for young readers, so that means downplaying some of the story’s harsher aspects. We know that Elliot’s parents are incapable of learning how to take care of him. We are also assured that they love him, but we never know why they can’t shoulder their responsibilities. This makes the book appropriate for young readers, but to withdraw all blame on the parental side will add a layer of fear for those kids who encounter this book without some systematic prepping beforehand. It would be pretty easy for them to say, “Wait. I sometimes cry. I sometimes misbehave. Are my parents going to leave me with a strange family?”

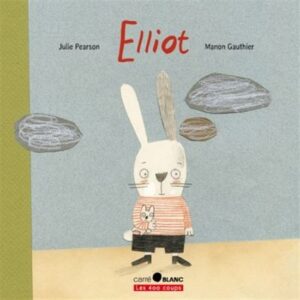

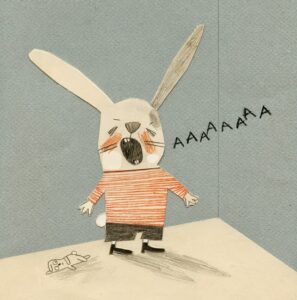

Artist Manon Gauthier is the illustrator behind this book and here she employs a very young, accessible style. Bunnies are, for whatever reason, the perfect animal stand-in for human problems and relationships, and so this serious subject matter is made younger on sight. With this in mind, the illustrator’s style brings with it at least one problematic issue. I suspect that many people that come to this book will approach it in much the same way that I did. My method of reading picture books is to grab a big bunch of them and carry them to my lunch table. Then I go through them and try to figure out which ones are delightful, which ones are terrible, and which ones are merely meh (that would be the bulk). I picked up Elliot and had the reaction to it that I’m sure a lot of people will. “Aw. What a cute little bunny book” thought I. It was around the time Elliot was taken from his family for the second time that I began to catch on to what I was reading. A fellow children’s librarian read the book and speculated that it was the choice of artist that was the problem. With its adorable bunny on the cover there is little indication of the very serious content inside. I’ve pondered this at length and in the end I’ve decided that it’s not the style of the art that’s problematic here but the choice of which image to show on the book jacket. Considering the subject matter, the publisher might have done better to go the The Day Leo Said, ‘I Hate You’ route. Which is to say, show a cover where there is a problem. On the back of the book is a picture of Elliot looking interested but wary on the lap of a motherly rabbit. Even that might have been sufficiently interesting to make readers take a close read of the plot description on the bookflap. It certainly couldn’t have hurt.

Artist Manon Gauthier is the illustrator behind this book and here she employs a very young, accessible style. Bunnies are, for whatever reason, the perfect animal stand-in for human problems and relationships, and so this serious subject matter is made younger on sight. With this in mind, the illustrator’s style brings with it at least one problematic issue. I suspect that many people that come to this book will approach it in much the same way that I did. My method of reading picture books is to grab a big bunch of them and carry them to my lunch table. Then I go through them and try to figure out which ones are delightful, which ones are terrible, and which ones are merely meh (that would be the bulk). I picked up Elliot and had the reaction to it that I’m sure a lot of people will. “Aw. What a cute little bunny book” thought I. It was around the time Elliot was taken from his family for the second time that I began to catch on to what I was reading. A fellow children’s librarian read the book and speculated that it was the choice of artist that was the problem. With its adorable bunny on the cover there is little indication of the very serious content inside. I’ve pondered this at length and in the end I’ve decided that it’s not the style of the art that’s problematic here but the choice of which image to show on the book jacket. Considering the subject matter, the publisher might have done better to go the The Day Leo Said, ‘I Hate You’ route. Which is to say, show a cover where there is a problem. On the back of the book is a picture of Elliot looking interested but wary on the lap of a motherly rabbit. Even that might have been sufficiently interesting to make readers take a close read of the plot description on the bookflap. It certainly couldn’t have hurt.

Could this book irreparably harm a child if they encountered it unawares? Short Answer: No. Long Answer: Not even slightly. But could they be disturbed by it? Sure could. I don’t think it would take much stretch of the imagination to figure that the child that encounters this book unawares without any context could be potentially frightened by what the book is implying. I’ll confess something to you, though. As I put this book out for review, my 4-year-old daughter spotted it. And, since it’s a picture book, she asked if I could read it to her. I had a moment then of hesitation. How do I give this book enough context before a read? But at last I decided to explain beforehand as much as I could about children with developmental disabilities and the foster care system. In some ways this talk boiled down to me explaining to her that some parents are unfit parents, a concept that until this time had been mercifully unfamiliar to her. After we read the book, her only real question was why Elliot had to go through so many foster care families, so we got to talk about that for a while It was a pretty valuable conversation and not one I would have had with her without the prompting of the book itself. So outside of children that have an immediate need of this title, there is a value to the contents.

What’s that old Ranganathan rule? Ah, yes. “Every book its reader.” Trouble is, sometimes the readers exist but the books don’t. Books like Elliot are exceedingly rare sometimes. I’d be the first to admit that Pearson and Gauthier’s book may bite off a bit more than it can chew, but it’s hardly a book built on the shaky foundation of mere good intentions. Elliot confronts issues few other titles would dare, and if it looks like one thing and ends up being another, that’s okay. There will certainly be parents that find themselves unexpectedly reading this to their kids at night only to discover partway through that this doesn’t follow the usual format or rules. It’s funny, strange, and sad but ultimately hopeful at its core. Social workers, teachers, and parents will find it one way or another, you may rest assured. For many libraries it will end up in the “Parenting” section. Not for everybody (what book is?) but a godsend to a certain few.

On shelves April 4th.

Source: Galley sent from publicist for review.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 3/12/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

Canadian children's books,

Best Books,

Groundwood Books,

wordless picture books,

JonArno Lawson,

Sydney Smith,

Canadian picture books,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 picture books,

2015 reviews,

Add a tag

Sidewalk Flowers

Sidewalk Flowers

By JonArno Lawson

Illustrated by Sydney Smith

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1-55498-431-2

Ages 3-6

On shelves March 17th

When you live in a city, nature’s successes can feel like impositions. We have too many pigeons. Too many squirrels. Too many sparrows, and roaches, and ants. Too many . . . flowers? Flowers we don’t seem to mind as much but we certainly don’t pay any attention to them. Not if we’re adults, anyway. Kids, on the other hand, pay an exquisite amount of attention to anything on their eye level. Particularly if it’s a spot of tangible beauty available to them for the picking. Picture books have so many functions, but one of them is tapping into the mindset of people below the ages of 9 or 10. A good picture book gets down to a child’s eye level, seeing what they’re seeing, reveling in what they’re reveling in. Perspective and subject matter, art and heart, all combine with JonArno Lawson and Sydney Smith’s Sidewalk Flowers. Bright spots of joy and comfort, sometimes it takes a kid to see what anyone else might claim isn’t even there.A girl and her father leave the grocery to walk the city streets home. As he leads, he is blind to the things she sees. A tattooed stranger. A woman in a cab. And on one corner, small dandelions poking out of the sidewalk. As the two walk she finds more and more of the beauties, and gathers them into a bouquet. Once that’s done she finds ways of giving them out. Four to the dead bird on the sidewalk. One to the homeless man asleep on the bench. Five tucked into the collar of a dog. Home once more she plants flowers in her mother’s hair and behind her brothers’ ears. Then, with the last blossom, she tucks it behind her own ear. That done, she’s ready to keep walking, watching and noticing.

Now JonArno Lawson, I know. If I had my way his name would grace the tongue of every children’s librarian in America. However, he is both Canadian and a poet and the dual combination dooms his recognition in the United States. Canadians, after all, cannot win most of the American Library Association awards and poets are becoming increasingly rare beasts in the realm of children’s literature. Time was you couldn’t throw a dart without hitting one or two children’s poets (albeit the slow moving ones). Now it sometimes feels like there are only 10-15 in any given year. Treat your children and read them The Man in the Moon Fixer’s Mask if ever you get a chance. Seen in this light, the idea of a poet turned wordless picture book author is unusual. It’s amazing that a man of words, one that finds such satisfaction in how they are strung together, could step back and realize from the get-go that this story could be best served only when the words themselves were removed.

A picture book as an object is capable of bringing to the attention of the reader those small moments of common grace that make the world ever so slightly better. In an interview with Horn Book editor Roger Sutton, author JonArno Lawson cited the inspiration for this book: “Basically, I was walking with my daughter down an ugly street, Bathurst Street, in Toronto, not paying very close attention, when I noticed she was collecting little flowers along the way . . . What struck me was how unconscious the whole thing was. She wasn’t doing it for praise, she was just doing it.” I love this point. The description on the back of this book says that “Each flower becomes a gift, and whether the gift is noticed or ignored, both giver and recipient are transformed by their encounter.” I think I like Lawson’s interpretation better. What we have here is a girl who is bringing beauty with her, and disposing of it at just the right times. It becomes a kind of act of grace. Small beauties. Small person.

A picture book as an object is capable of bringing to the attention of the reader those small moments of common grace that make the world ever so slightly better. In an interview with Horn Book editor Roger Sutton, author JonArno Lawson cited the inspiration for this book: “Basically, I was walking with my daughter down an ugly street, Bathurst Street, in Toronto, not paying very close attention, when I noticed she was collecting little flowers along the way . . . What struck me was how unconscious the whole thing was. She wasn’t doing it for praise, she was just doing it.” I love this point. The description on the back of this book says that “Each flower becomes a gift, and whether the gift is noticed or ignored, both giver and recipient are transformed by their encounter.” I think I like Lawson’s interpretation better. What we have here is a girl who is bringing beauty with her, and disposing of it at just the right times. It becomes a kind of act of grace. Small beauties. Small person.

Now we know from Roger’s interview that Lawson created a rough dummy of the book and the way he envisioned it, but how artist Sydney Smith chose to interpret that storyline seems to have been left entirely up to him. Wordless books give an artist such remarkable leeway. I’ve seen some books take that freedom and waste it on the maudlin, and I’ve seen others make a grab for the reader’s heart only to miss it by a mile. The overall feeling I get from Sidewalk Flowers, though, is a quiet certitude. This is not a book that is pandering for your attention and love. Oh, I’m sure that some folks out there will find the sequence with the homeless man on the bench a bit too pat, but to those people I point out the dead bird. How on earth does an artist show a girl leaving flowers by a dead bird without tripping headlong into the trite or pat? I’ve no idea. All I know is that Smith manages it.

Much of this has to do with the quality of the art. Smith’s tone is simultaneously serious and chock full of a kind of everyday wonder. His city is not too clean, not too dirty, and just the right bit of busy. For all that it’s a realistic urban setting, there’s something of the city child to its buzz and bother. A kid who grows up in a busy city finds a comfort in its everyday bustle. There are strangers here, sure, but there’s also a father who may be distracted but is never any more than four or five feet away from his daughter. Her expressions remain muted. Not expressionless, mind you, but you pay far more attention to her actions than her emotions. What she is feeling she’s keeping to herself. As for the panels, Smith knows how to break up each page in a different way. Sometimes images will fill an entire page. Other times there will be panels and white borders. Look at how the shelves in a secondhand shop turn the girl and her dad into four different inadvertent panels. Or how the dead bird sequence can be read top down or side-to-side with equal emotional gut punches.

Much of this has to do with the quality of the art. Smith’s tone is simultaneously serious and chock full of a kind of everyday wonder. His city is not too clean, not too dirty, and just the right bit of busy. For all that it’s a realistic urban setting, there’s something of the city child to its buzz and bother. A kid who grows up in a busy city finds a comfort in its everyday bustle. There are strangers here, sure, but there’s also a father who may be distracted but is never any more than four or five feet away from his daughter. Her expressions remain muted. Not expressionless, mind you, but you pay far more attention to her actions than her emotions. What she is feeling she’s keeping to herself. As for the panels, Smith knows how to break up each page in a different way. Sometimes images will fill an entire page. Other times there will be panels and white borders. Look at how the shelves in a secondhand shop turn the girl and her dad into four different inadvertent panels. Or how the dead bird sequence can be read top down or side-to-side with equal emotional gut punches.

The placement of each blossom deserves some credit as well. Notice how Smith (or was it Lawson?) chooses to show when the flowers are bestowed. You almost never see the girl place the flowers. Often you only see them after the fact, as the bird or dog or mother remains the focus of the panel and the girl hurries away. The father is never bedecked, actually. He seems to be the only person in the story who isn’t blessed by the gifts, but that’s probably because he’s a stand-in more than a parent. For adults reading this book, he’s a colorless reason not to worry about the girl’s capers. His purpose is to help her travel across the course of the book. Then, at the end, she takes the last remaining daisy, tucks it behind her ear, and walks onto the back endpapers where the pattern changes from merely a lovely conglomeration of flower and bird images to a field. A field waiting to be explored.

The use of color is probably the detail the most people will notice, even on a first reading of the story. In interviews Lawson has said that folks have told him that the girl’s hoodie reminds them of Peter in The Snowy Day or Little Red Riding Hood. She’s a spot of read traveling through broken gray. Her flowers are always colorful, and then there are those odd little blasts of color along her path. The dress of a woman at a bus stop is filled with flowers of its own. The oranges of a fruit stand beckon. The closer the girl approaches her home, the brighter the colors become. That grey wash that filled the lawns in the park turn a sweet pure green. As the girl climbs the steps to her mother (whose eyes are never seen), even her dad has taken a rosy hue to his cheeks.

After you pick up your 400th new baby book OR story about an animal that wants to dance ballet OR tale of a furry woodland creature that thinks that everyone has forgotten its birthday, you begin thinking that all the stories that could possibly be told to children have been written already. Do not fall into this trap. If Sidewalk Flowers teaches us nothing else it is that a single child could inspire a dozen picture books in the course of a single hour, let alone a day. There’s a reason folks are singing this book’s praises from Kalamazoo to Calgary. It’s a book that reminds you why we came up with the notion of wordless picture books in the first place. Affecting, efficient, moving, kind. Lawson’s done the impossible. He wrote poetry into a book without a single word, and you wouldn’t have it any other way.

On shelves March 17th.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher.

Like This? Then Try:

- Big Red Lollipop by Rukhsana Khan – For another picture book about grace.

- Knuffle Bunny by Mo Willems – For a tale of a girl and her father out for a walk in the city.

- The Silver Button by Bob Graham – For a tale that matches this one in terms of small city moments and tone.

Blog Reviews: Nine Kinds of Pie

Professional Reviews: A star from Kirkus

Interviews: Roger Sutton talks with JonArno Lawson about the book.

Misc: I can’t be the only person out there who thought of this comic after reading this book.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 4/25/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Kids Can Press,

Best Books,

Ashley Spires,

Canadian picture books,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 picture books,

2014 reviews,

Reviews,

picture books,

Add a tag

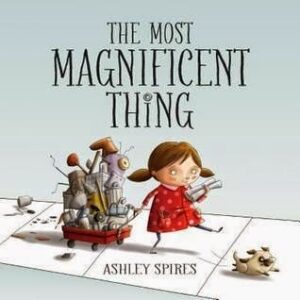

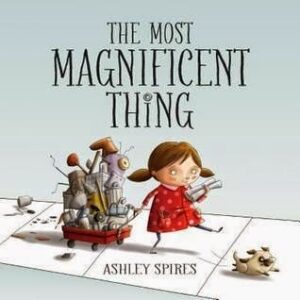

The Most Magnificent Thing

The Most Magnificent Thing

By Ashley Spires

Kids Can Press

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1-55453-704-4

Ages 3-7

On shelves now

I was at a conference of math enthusiasts the other day to discuss kids and the state of math related children’s books. Not my usual scene but I was open to it. Despite what some might fear, the day was thoroughly fascinating and the mathematicians in attendance made many fine and salient points that I had never thought to consider. At one point they took it upon themselves to correct some common math-related misunderstandings that have grown over the years. Most fascinating was the idea of trial and error. Kids today live in an era where it often feels to them that if they don’t get something right the first time then they should just give it up and try something else. It’s hard to make them understand that in a lot of professions, math amongst them, much of the job consists of making mistakes and tinkering for long periods of time before getting to the ultimate solution. It got me to thinking about how there really aren’t a lot of children’s books out there that tackle this subject. Or, for those few that do, tackle it well. The remarkable thing then about a book like The Most Magnificent Thing by Ashley Spires isn’t just the way in which she’s gone about discussing this issue, but also the fact that it works as brilliantly as it does. This is the anti-perfection picture book. The one that dares to suggest that maybe a little trial and error is necessary when trying to get something right.

A girl and her dog are best friends. They do everything together from exploring to racing to making things. So when the girl has an idea one day for “the most MAGNIFICENT thing” that they can make together, the dog has no objection. Plans are drawn up, supplies gathered, and the work begins. And everything seems to be fine until it becomes infinitely clear that the thing she has made? It’s all wrong! Not a problem. She tosses it and tries again. And again. And again. Soon frustration turns to anger and anger into a whopping great temper tantrum. Just when the girl is on the brink of giving up, her doggie partner in crime suggests a walk. And when they return they realize that even if they haven’t gotten everything right yet, the previous attempts did a right thing here or a right thing there. And when you put those parts together what you’ll have might not be exactly like it was up in your brain, but it’ll be a truly magnificent thing just the same.

I think perhaps the main reason we don’t see a lot of books about kids trying and failing is that this sort of plot doesn’t make for a natural picture book. I won’t point any fingers, but the usual plot about success follows this format: Hero tries. Hero fails. Hero tries. Hero fails. Hero tries. Hero succeeds. Now hero is an instant pro. You see the problem. I’ve seen this plotline used on everything from learning to ride a bike to playing an instrument. And what Spires has done here that’s so marvelous is show that there’s a value in failure. A value that won’t yield success unless you go over your notes, rethink what you’ve already thought, reexamine the problem, and try it from another angle. In this book the failure is continual and incredibly frustrating. The girl actually has quite a bit of chutzpah, since she completes at least eleven mistakes before finally hitting on a solution. Useful bits and pieces are culled, but it’s also worth noting that the inventions left behind, while they don’t do her much good, are claimed by other people with other ideas. It sort of reinforces the notion that even as you work towards your own goals, your process might be useful to other people, whether or not you recognize that fact at the time.

I think perhaps the main reason we don’t see a lot of books about kids trying and failing is that this sort of plot doesn’t make for a natural picture book. I won’t point any fingers, but the usual plot about success follows this format: Hero tries. Hero fails. Hero tries. Hero fails. Hero tries. Hero succeeds. Now hero is an instant pro. You see the problem. I’ve seen this plotline used on everything from learning to ride a bike to playing an instrument. And what Spires has done here that’s so marvelous is show that there’s a value in failure. A value that won’t yield success unless you go over your notes, rethink what you’ve already thought, reexamine the problem, and try it from another angle. In this book the failure is continual and incredibly frustrating. The girl actually has quite a bit of chutzpah, since she completes at least eleven mistakes before finally hitting on a solution. Useful bits and pieces are culled, but it’s also worth noting that the inventions left behind, while they don’t do her much good, are claimed by other people with other ideas. It sort of reinforces the notion that even as you work towards your own goals, your process might be useful to other people, whether or not you recognize that fact at the time.

Spires doesn’t cheat either. Our unnamed heroine idea is actually clear cut about what she wants to make from the start. On the page where it reads, “One day, the girl has a wonderful idea. She is going to make the most MAGNIFICENT thing” you can see her on her scooter explaining her idea to her now thoroughly exhausted pup. It’s only on the last page that we learn that the thing in question was to be a pug-sized sidecar for the aforementioned scooter.

Now Ms. Spires is no newbie to the world of children’s literature. If you have not seen her Binky the Space Cat graphic novel series for kids, it is about time you hied thee hence and found those puppies. In them, you will discover that not only is she remarkably good at the subtle visual gag, but that her writing is just tiptop. Some of the choices she made for this book were fascinating to me. It’s written in the present tense. Neither the girl nor the dog has a name. At the same time it’s incredibly approachable. I love how Spires relates the girl’s travails. The final solution is also all the better because even with her success it’s not perfectly perfect. “It leans a little to the left, and it’s a bit heavier than expected. The color could use a bit of work, too. But it’s just what she wanted!” Perfection can be a terrible thing to strive for. Sometimes, just getting it right can be enough.

And yes, I have to mention it at some point: It’s about a scientifically minded girl character. Now you might feel like this ain’t no big a thing, but let me assure you that when I was wracking my brain to come up with readalikes for this title, I came up nearly empty. Picture books where girls are into nature science? Commonplace. But books where girls are into math or invention? Much more difficult. There are a couple exception to the rule (Violet the Pilot by Steve Breen, Rosie Revere, Engineer by Andrea Beaty, and Oh No! Or How My Science Project Destroyed the World by Mac Barnett come to mind) but by and large they are rare. Yet if this had been a book where the whole point was something along the lines of even-girls-can-love-science I would have loathed it. The joy of The Most Magnificent Thing is that the girl’s goal is the focus, not the girl herself. Her love of tinkering is just natural. A fact of life. As well it should be.

And yes, I have to mention it at some point: It’s about a scientifically minded girl character. Now you might feel like this ain’t no big a thing, but let me assure you that when I was wracking my brain to come up with readalikes for this title, I came up nearly empty. Picture books where girls are into nature science? Commonplace. But books where girls are into math or invention? Much more difficult. There are a couple exception to the rule (Violet the Pilot by Steve Breen, Rosie Revere, Engineer by Andrea Beaty, and Oh No! Or How My Science Project Destroyed the World by Mac Barnett come to mind) but by and large they are rare. Yet if this had been a book where the whole point was something along the lines of even-girls-can-love-science I would have loathed it. The joy of The Most Magnificent Thing is that the girl’s goal is the focus, not the girl herself. Her love of tinkering is just natural. A fact of life. As well it should be.

On the back bookflap for this book we are able to discover the following information about Ms. Spires: “Ashley has always loved to make things and she knows the it-turned-out-wrong frustration well! All of her books have at one point or another made her cry, scream and tear her hair out as she tried to get them JUST RIGHT.” I guess that children’s authors really are the finest authorities on trial and error. They know frustration. They know rejected drafts. They know how much work it takes to get a book just right. And when all the right elements come together at last? Then you get a book like The Most Magnificent Thing. I don’t know how long it took Ms. Spires to write and illustrate this. All I know is that it was worth it. In the end, it’s precisely the kind of book we need for kids these days. Perfection is a myth. Banged up, beat up, good enough can sometimes be the best possible solution to a problem. A lesson for the 21st century children everywhere.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Other Blog Reviews:

Professional Reviews:

Misc: Just wanted to point out this little note on the publication page. It’s easy to miss but when discussing the art it reads, “The artwork in this book was rendered digitally with lots of practice, two hissy fits and one all out tantrum.” Cute.

Videos:

Here’s the official book trailer:

The Most Magnificent Thing Book Trailer from Kids Can Press on Vimeo.

And here we have the world’s most adorable author hacking her own book:

By:

Aline Pereira,

on 8/22/2012

Blog:

PaperTigers

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Canada,

Barbara Reid,

Melanie Watt,

Eventful World,

children's literature events,

Michael Martchenko,

Canadian Children's Book Centre,

Genevieve Cote,

Canadian Children's Book Week,

Cultures and Countries,

Rebecca Bender,

Canadian picture books,

canadian children's book authors,

canadian picture book illustrators,

The Art of the Picture Book Exhibition and Auction,

Add a tag

The Canadian Children’s Book Centre Presents: The Art of the Picture Book Exhibition ~ by Holly Kent, Sales and Marketing Manager, The Canadian Children’s Book Centre

(Part 3 of 3. Read Part 1 “The Canadian Children’s Book Centre Presents TD Canadian Children’s Book Week” here and Part 2 “The Canadian Children’s Book Centre’s TD Grade One Book Giveaway Program” here.)

It is through the support of generous sponsors, donations, and our members and subscribers that the Canadian Children’s Book Centre is able to run its many programs. We also hold fundraising events – one of the most exciting being The Art of the Picture Book Exhibition and Auction.

It is through the support of generous sponsors, donations, and our members and subscribers that the Canadian Children’s Book Centre is able to run its many programs. We also hold fundraising events – one of the most exciting being The Art of the Picture Book Exhibition and Auction.

Over 80 original illustrations from Canadian picture books will be on exhibit at the world-famous Montreal Museum of Fine Art in fall 2012. Some of the most stunning images from Canadian picture books will be part of the exhibition celebrating Canadian children’s book illustrations. The exhibit will run from September 11 to October 14.

The kicker (for the Canadian Children’s Book Centre) is that each piece has been graciously donated by leading Canadian illustrators and the sale of these pieces will raise funds to support our programs, publications, and operating costs.

Works have been donated by renowned artists including Rebecca Bender (image on left), Geneviève Côté, Barbara Reid, Michael Martchenko, Mélanie Watt, and many more.

The month-long exhibit will be followed by Take Home an Original, an auction of the original art, on the evening of October 16, 2012.

The  Canadian Children’s Book Centre (CCBC) is a national, not-for-profit organization founded in 1976. We are dedicated to encouraging, promoting and supporting the reading, writing, illustrating and publishing of Canadian books for young readers. Our programs, publications, and resources help teachers, librarians, booksellers and parents select the very best for young readers.

Canadian Children’s Book Centre (CCBC) is a national, not-for-profit organization founded in 1976. We are dedicated to encouraging, promoting and supporting the reading, writing, illustrating and publishing of Canadian books for young readers. Our programs, publications, and resources help teachers, librarians, booksellers and parents select the very best for young readers.

At the heart of our work at the Canadian Children’s Book Centre is our love for the books that get published in Canada each year, and our commitment to raising awareness of the quality and variety of Canadian books for young readers.

Our programs, such as TD Canadian Children’s Book Week and the TD Grade One Book Giveaway, are designed to introduce young Canadian readers not only to the books all around them, but to the authors and illustrators that create them. Our quarterly magazine Canadian Children’s Book News and the annual Best Books for Kids & Teens selection guide are designed to help parents, librarians and educators discover the world of Canadian books and to help them to select the best reading material for young readers.

We are thrilled to have The Canadian Children’s Book Centre join us as PaperTigers’ Global Voices Guest Blogger for the month of August. Part 1 of the series “The Canadian Children’s Book Centre Presents TD Canadian Children’s Book Week” was posted here. Part 2 “The Canadian Children’s Book Centre’s TD Grade One Book Giveaway Program” was posted here.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 5/1/2012

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Harry Potter,

Uncategorized,

movie news,

math,

knitting,

Roger Sutton,

Canadian children's books,

Brian Selznick,

Caldecott Award,

Dandi Daley Mackall,

Edgar Awards,

street photography,

Matthew Kirby,

Canadian bloggers,

Canadian picture books,

New Yorkers reading,

sassy clocks,

Add a tag

The laptop of my infinite sadness continues to remain broken which wrecks a certain special kind of havoc with my gray cells. To distract myself, I plunge headlong into the silliest news of the week. Let’s see if there’s anything here to console a battered Bird brain (something tells me that didn’t come out sounding quite right…).

The laptop of my infinite sadness continues to remain broken which wrecks a certain special kind of havoc with my gray cells. To distract myself, I plunge headlong into the silliest news of the week. Let’s see if there’s anything here to console a battered Bird brain (something tells me that didn’t come out sounding quite right…).

- The best news of the day is that Matthew Kirby was the recent winner of the Edgar Award for Best Mystery in the juvenile category for his fabuloso book Icefall. My sole regret is that it did not also win an Agatha Award for “traditional mystery” in the style of Agatha Christie. Seems to me it was a shoo-in. I mean, can you think of any other children’s book last year that had such clear elements of And Then There Were None? Nope. In any case, Rocco interviews the two winners (the YA category went to Dandi Daley Mackall) here and here.

- It’s so nice when you find a series on Facebook and then discover it has a website or blog equivalent in the “real world” (howsoever you choose to define that term). The Underground New York Public Library name may sound like it’s a reference to our one and only underground library (the Andrew Heiskell branch, in case you were curious) but it’s actually a street photography site showing what New Yorkers read on the subways. Various Hunger Games titles have made appearances as has Black Heart by Holly Black and some other YA/kid titles. Just a quick word of warning, though. It’s oddly engaging. You may find yourself flipping through the pages for hours.

- A reprint of Roger Sutton’s 2010 Ezra Jack Keats Lecture from April 2011 has made its way online. What Hath Harry Wrought? puts the Harry Potter phenomenon in perspective now that we’ve some distance. And though I shudder to think that Love You Forever should get any credit for anything ever (growl grumble snarl raspberry) what Roger has to say here is worthy of discussion.

- And in my totally-not-surprised-about-this department… From Cynopsis Kids:

“Fox Animation acquires the feature film rights to the kid’s book The Hero’s Guide to Saving your Kingdom, per THR. A fairy tale mashup by first-time author by Christopher Healy and featuring illustrations by Todd Harris, revolves around the four princes from Cinderella, Snow White, Rapunzel and Sleeping Beauty. Chernin Entertainment (Rise of Planet of the Apes) is set to produce the movie. Walden Pond Press/HarperCollins Children’s Books release The Hero’s Guide to Saving Your Kingdom (432 pages) today.”

If y’all haven’t read The Hero’s Guide to Saving Your King

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 7/4/2011

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Uncategorized,

Canadian children's books,

Kids Can Press,

picture book reviews,

Matthew Forsythe,

2011 picture books,

2011 reviews,

2011 Canadian titles,

Annika Dunklee,

Canadian picture books,

Add a tag

My Name Is Elizabeth

My Name Is Elizabeth

By Annika Dunklee

Illustrated by Matthew Forsythe

Kids Can Press

$14.95

ISBN: 978-1-55453-560-6

Ages 4-8

On shelves September 1, 2011

The human capacity to garble a first name, even a simple or common one, is without limit. I should know. My name is Elizabeth. My preferred nickname is “Betsy”, which is not intuitive. Generally speaking, one should never assume what another person’s nickname is. In my day I have shouldered countless calls of “Liz”, more than one “Betty”, and the occasional (and unforgivable) “Eliza”. Still, my heart goes out to kids with fresh and original names that get mangled in the garbled mouths of well-meaning adults. For them, the name “Elizabeth” may seem simple in comparison. Yet as My Name Is Elizabeth! makes clear from the get-go, there is no name so simple that someone can’t butcher it in some manner.

Elizabeth loves her name. Who wouldn’t? It has a lot of advantages, like length and how it sounds when you work the syllables out of your mouth. The downside? Everyone just gives you whatever nickname they think suits you. If it’s not Lizzy then it’s Beth. If it’s not Liz then it’s something “Not. Even. Close.” like Betsy. At last Elizabeth can take it no longer. To the general world she declares her full name (“Elizabeth Alfreda Roxanne Carmelita Bluebell Jones”) or Elizabeth if you like. Finally, everyone gets it right. Even her little brother (though she might bend the rules a bit for his attempted “Wizabef”).

One has to assume that any author with the first name “Annika” would know from whence she speaks with a book like this. Kids don’t have much to call their own when they’re young. Their clothes and toys are purchased by their parents and can be changed and taken away at any moment. Their names, however, are their own. Some of them realize early on that these names have power, and that they themselves have power over those names. They can insist that they be called one thing or another. They cannot make anyone actually obey these requests, but they can try, doggone it. A lot of kids fantasize about changing their names, but Elizabeth embraces her name. Her beef with nicknames wins you over because there is something inherently jarring about being given the wrong label. We are inclined to become our names, even when we don’t want to.

This story contains a tiny cry for independence by a character that is insistent without being bratty. In the end, Elizabeth proves to be a grand role model for those kids. She’s precocious without being insufferable (a rare trait in a picture book heroine). I like the lesson she teaches kids here too. It’s easy to let the world make assumptions about you and walk all over you. And it’s particularly hard to stand up to people when they are wrong but well meaning. You might be inclined to let their mistakes go and not raise a fuss, but when you claim your own name you claim how the world sees you. This book highlights a small battle that any kid can relate to.

This story contains a tiny cry for independence by a character that is insistent without being bratty. In the end, Elizabeth proves to be a grand role model for those kids. She’s precocious without being insufferable (a rare trait in a picture book heroine). I like the lesson she teaches kids here too. It’s easy to let the world make assumptions about you and walk all over you. And it’s particularly hard to stand up to people when they are wrong but well meaning. You might be inclined to let their mistakes go and not raise a fuss, but when you claim your own name you claim how the world sees you. This book highlights a small battle that any kid can relate to.

The two-color picture book is not unheard of these days but it is less common that it was back in th

Who Broke the Teapot?!

Who Broke the Teapot?! Generally when I write a picture book review I have a pretty standard format that I adhere to. I start with an opening paragraph (done), move on to a description of the plot in the next paragraph (so far, so good), and in the third paragraph I talk about some aspect of the writing. It could be the overall theme or the writing or the plotting. After that I talk about the art. This pattern is almost never mucked with . . . until today!! Because ladies and gents, you have just GOT to take a gander at what Mr. Slavin’s doing here with his acrylics. Glancing at the art isn’t going to do it. You have to pick this book up and really inspect the art. For the bulk of it the human characters are your usual cartoony folks. Very smooth paints. But even the most cursory glance at the backgrounds yields rewards. The walls are textured with thick, luscious paints adhering to different patterns. There’s even a touch of mixed media to the old affair, what with cat’s yarn being real thread and all (note too how Slavin seamlessly makes it look as if the yarn is wrapped around the legs of the high chair). Then the typography starts to get involved. The second time the mom says “Who broke the teapot?!” the words look like the disparate letters of a rushed ransom note. As emotions heat up (really just the emotions of the mom, to be honest) the thick paints crunch when she says “CRUNCHED”, acquire zigzags as her temper unfurls, and eventually belie the smoothness of the characters’ skin when the texture invades the inside of the two-page spread of the now screaming mother’s mouth.

Generally when I write a picture book review I have a pretty standard format that I adhere to. I start with an opening paragraph (done), move on to a description of the plot in the next paragraph (so far, so good), and in the third paragraph I talk about some aspect of the writing. It could be the overall theme or the writing or the plotting. After that I talk about the art. This pattern is almost never mucked with . . . until today!! Because ladies and gents, you have just GOT to take a gander at what Mr. Slavin’s doing here with his acrylics. Glancing at the art isn’t going to do it. You have to pick this book up and really inspect the art. For the bulk of it the human characters are your usual cartoony folks. Very smooth paints. But even the most cursory glance at the backgrounds yields rewards. The walls are textured with thick, luscious paints adhering to different patterns. There’s even a touch of mixed media to the old affair, what with cat’s yarn being real thread and all (note too how Slavin seamlessly makes it look as if the yarn is wrapped around the legs of the high chair). Then the typography starts to get involved. The second time the mom says “Who broke the teapot?!” the words look like the disparate letters of a rushed ransom note. As emotions heat up (really just the emotions of the mom, to be honest) the thick paints crunch when she says “CRUNCHED”, acquire zigzags as her temper unfurls, and eventually belie the smoothness of the characters’ skin when the texture invades the inside of the two-page spread of the now screaming mother’s mouth. Now kids love a good mystery, and I’m not talking just the 9 and 10-year-olds. Virtually every single age of childhood has a weakness for books that set up mysterious circumstances and then reveal all with a flourish. Heck, why do you think babies like the game of peekaboo? Think of it as the ultimate example of mystery and payoff. Picture book mysteries are, however, far more difficult to write than, say, an episode of Nate the Great. You have to center the book squarely in the child’s universe, give them all the clues, and then make clear to the reader what actually happened. To do this you can show the perpetrator of the crime committing the foul deed at the start of the book or you can spot clues throughout the story pointing clearly to the miscreant. In the case of Who Broke the Teapot, Slavin teaches (in his own way) that old Sherlock Holmes phrase, “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

Now kids love a good mystery, and I’m not talking just the 9 and 10-year-olds. Virtually every single age of childhood has a weakness for books that set up mysterious circumstances and then reveal all with a flourish. Heck, why do you think babies like the game of peekaboo? Think of it as the ultimate example of mystery and payoff. Picture book mysteries are, however, far more difficult to write than, say, an episode of Nate the Great. You have to center the book squarely in the child’s universe, give them all the clues, and then make clear to the reader what actually happened. To do this you can show the perpetrator of the crime committing the foul deed at the start of the book or you can spot clues throughout the story pointing clearly to the miscreant. In the case of Who Broke the Teapot, Slavin teaches (in his own way) that old Sherlock Holmes phrase, “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.” I also love that the flashback does far more than explain who broke the teapot. It explains why exactly most of the members of this family are dwelling in a kind of generally accepted chaotic stew. You take it for granted when you first start reading. A kid’s hanging from a ceiling fan? Sure. Yeah. That happens. But the explanation, when it comes, belies that initial response. The parents don’t question his position so you don’t question it. That is your first mistake. Never take your lead from parents. And speaking of the flashback, let’s just stand aside for a moment and remember just how sophisticated it is to portray this concept in a picture book at all. You’re asking a child audience to accept that there is a “before” to every book they read. Few titles go back in time to explain how we got to where we are now. Slavin’s does so easily, and it will be the rare reader that can’t follow him on this trip back into the past.

I also love that the flashback does far more than explain who broke the teapot. It explains why exactly most of the members of this family are dwelling in a kind of generally accepted chaotic stew. You take it for granted when you first start reading. A kid’s hanging from a ceiling fan? Sure. Yeah. That happens. But the explanation, when it comes, belies that initial response. The parents don’t question his position so you don’t question it. That is your first mistake. Never take your lead from parents. And speaking of the flashback, let’s just stand aside for a moment and remember just how sophisticated it is to portray this concept in a picture book at all. You’re asking a child audience to accept that there is a “before” to every book they read. Few titles go back in time to explain how we got to where we are now. Slavin’s does so easily, and it will be the rare reader that can’t follow him on this trip back into the past.

It is through the support of generous sponsors, donations, and our members and subscribers that the

It is through the support of generous sponsors, donations, and our members and subscribers that the  Canadian Children’s Book Centre (CCBC)

Canadian Children’s Book Centre (CCBC)

Thanks so much, Elizabeth, for that wonderful review. I’m so very glad that you enjoyed the book!

Warm regards,

Bill

Hi Elizabeth,

A very proud big brother writing here, and delighted that you have discovered this remarkable talent who was just the kid in the highchair when I was 10. Like you, I inhale the detail in every book he produces. Such transcendent stuff!

Alas, we are indeed northern border other-siders… but Bill does have a stellar Canadian publishing track record, worth exploring.

Enough,

~ Jim

I know it well. Actually, I was very pleased to see this book prominently displayed in some bookstore windows when I took a trip to Stratford, ON this summer. Clearly he is beloved up there. Let’s see what we can do about transferring some of that love (or, at the very least, recognition).

Loved this immediately and have read it to every storytime and outreach group, booktalked it to other librarians and gotten a few of them to love it. It’s been a hit with everyone I’ve read it to. One of my favorites of the year!