new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Newton, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 8 of 8

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Newton in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: DanP,

on 7/6/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

myths,

apple,

alchemy,

bible,

gravity,

British,

physics,

isaac newton,

newton,

trinity college,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

Science & Medicine,

newton’s,

gravitational pull,

sarah dry,

The Newton Papers,

Add a tag

By Sarah Dry

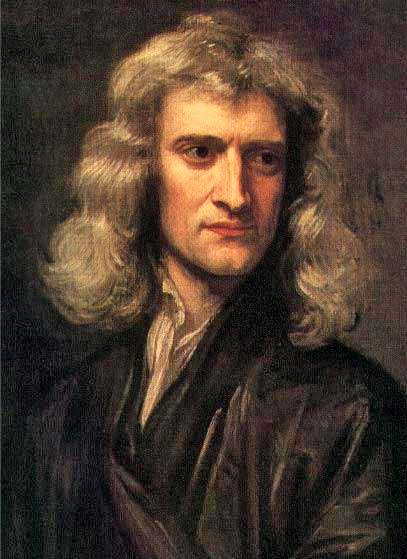

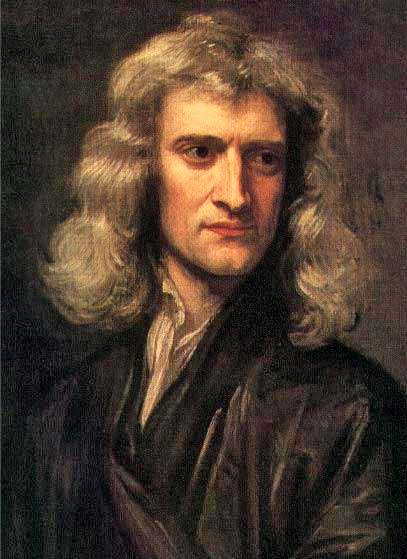

Nearly three hundred years since his death, Isaac Newton is as much a myth as a man. The mythical Newton abounds in contradictions; he is a semi-divine genius and a mad alchemist, a somber and solitary thinker and a passionate religious heretic. Myths usually have an element of truth to them but how many Newtonian varieties are true? Here are ten of the most common, debunked or confirmed by the evidence of his own private papers, kept hidden for centuries and now freely available online.

10. Newton was a heretic who had to keep his religious beliefs secret.

True. While Newton regularly attended chapel, he abstained from taking holy orders at Trinity College. No official excuse survives, but numerous theological treatises he left make perfectly clear why he refused to become an ordained clergyman, as College fellows were normally obliged to do. Newton believed that the doctrine of the Trinity, in which the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost were given equal status, was the result of centuries of corruption of the original Christian message and therefore false. Trinity College’s most famous fellow was, in fact, an anti-Trinitarian.

9. Newton never laughed.

False, but only just. There are only two specific instances that we know of when the great man laughed. One was when a friend to whom he had lent a volume of Euclid’s Elements asked what the point of it was, ‘upon which Sir Isaac was very merry.’ (The point being that if you have to ask what the point of Euclid is, you have already missed it.) So far, so moderately funny. The second time Newton laughed was during a conversation about his theory that comets inevitably crash into the stars around which they orbit. Newton noted that this applied not just to other stars but to the Sun as well and laughed while remarking to his interlocutor John Conduitt ‘that concerns us more.’

8. Newton was an alchemist.

True. Alchemical manuscripts make up roughly one tenth of the ten million words of private writing that Newton left on his death. This archive contains very few original treatises by Newton himself, but what does remain tells us in minute detail how he assessed the credibility of mysterious authors and their work. Most are copies of other people’s writings, along with recipes, a long alchemical index and laboratory notebooks. This material puzzled and disappointed many who encountered it, such as biographer David Brewster, who lamented ‘how a mind of such power, and so nobly occupied with the abstractions of geometry, and the study of the material world, could stoop to be even the copyist of the most contemptible alchemical work, the obvious production of a fool and a knave.’ While Brewster tried to sweep Newton’s alchemy under the rug, John Maynard Keynes made a splash when he wrote provocatively that Newton was the ‘last of the magicians’ rather than the ‘first king of reason.’

7. Newton believed that life on earth (and most likely on other planets in the universe) was sustained by dust and other vital particles from the tails of comets.

True. In Book 3 of the Principia, Newton wrote extensively how the rarefied vapour in comet’s tails was eventually drawn to earth by gravity, where it was required for the ‘conservation of the sea, and fluids of the planets’ and was most likely responsible for the ‘spirit’ which makes up the ‘most subtle and useful part of our air, and so much required to sustain the life of all things with us.’

6. Newton was a self-taught genius who made his pivotal discoveries in mathematics, physics and optics alone in his childhood home of Woolsthorpe while waiting out the plague years of 1665-7.

False, though this is a tricky one. One of the main treasures that scholars have sought in Newton’s papers is evidence for his scientific genius and for the method he used to make his discoveries. It is true that Newton’s intellectual achievement dwarfed that of his contemporaries. It is also true that as a 23 year-old, Newton made stunning progress on the calculus, and on his theories of gravity and light while on a plague-induced hiatus from his undergraduate studies at Trinity College. Evidence for these discoveries exists in notebooks which he saved for the rest of his life. However, notebooks kept at roughly the same time, both during his student days and his so called annus mirabilis, also demonstrate that Newton read and took careful notes on the work of leading mathematicians and natural philosophers, and that many of his signature discoveries owe much to them.

5. Newton found secret numerological codes in the Bible.

True. Like his fellow analysts of scripture, Newton believed there were important meanings attached to the numbers found there. In one theological treatise, Newton argues that the Pope is the anti-Christ based in part on the appearance in Scripture of the number of the name of the beast, 666. In another, he expounds on the meaning of the number 7, which figures prominently in the numbers of trumpets, vials and thunders found in Revelation.

4. Newton had terrible handwriting, like all geniuses.

False. Newton’s handwriting is usually clear and easy to read. It did change somewhat throughout his life. His youthful handwriting is slightly more angular, while in his old age, he wrote in a more open and rounded hand. More challenging than deciphering his handwriting is making sense of Newton’s heavily worked-over drafts, which are crowded with deletions and additions. He also left plenty of very neat drafts, especially of his work on church history and doctrine, which some considered to be suspiciously clean, evidence, said his 19th century cataloguers, of Newton’s having fallen in love with his own hand-writing.

3. Newton believed the earth was created in seven days.

True. Newton believed that the Earth was created in seven days, but he assumed that the duration of one revolution of the planet at the beginning of time was much slower than it is today.

2. Newton discovered universal gravitation after seeing an apple fall from a tree.

False, though Newton himself was partly responsible for this myth. Seeking to shore up his legacy at the end of his life, Newton told several people, including Voltaire and his friend William Stukeley, the story of how he had observed an apple falling from a tree while waiting out the plague in Woolsthorpe between 1665-7. (He never said it hit him on the head.) At that time Newton was struck by two key ideas—that apples fall straight to the center of the earth with no deviation and that the attractive power of the earth extends beyond the upper atmosphere. As important as they are, these insights were not sufficient to get Newton to universal gravitation. That final, stunning leap came some twenty years later, in 1685, after Edmund Halley asked Newton if he could calculate the forces responsible for an elliptical planetary orbit.

1. Newton was a virgin.

Almost certainly true. One bit of evidence comes via Voltaire, who heard it from Newton’s physician Richard Mead and wrote it up in his Letters on England, noting that unlike Descartes, Newton was ‘never sensible to any passion, was not subject to the common frailties of mankind, nor ever had any commerce with women.’ More substantively, there is Newton’s lifelong status as a self-proclaimed godly bachelor who berated his friend Locke for trying to ‘embroil’ him with women and who wrote passionately about how other godly men struggled to tame their lust.

Sarah Dry is a writer, independent scholar, and a former post-doctoral fellow at the London School of Economics. She is the author of The Newton Papers: The Strange and True Odyssey of Isaac Newton’s Manuscripts. She blogs at sarahdry.wordpress.com and tweets at @SarahDry1.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

Image credit: Portrait of Isaac Newton by Sir Godfrey Kneller. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post True or false? Ten myths about Isaac Newton appeared first on OUPblog.

.jpeg?picon=3304)

By: Leslie Ann Clark,

on 2/17/2013

Blog:

Leslie Ann Clark's Skye Blue Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Lae Dee Bugg,

artist,

fun,

cartoons,

inspiration,

art,

computer,

memory,

goals,

baby chick,

Newton,

Peepsqueak,

Add a tag

2 1/2 years ago I bought my trusty little Apple laptop. The other day I was working on it and up came a window telling me I had about 100 GB of information on it! This memory includes programs that I run, but most of it is ART!! Fabric design, product concepts, children’s books and more. Peepsqueak and his friends, Newton my lamb and his friends, a friendly new elephant and monkey, some babies, some clowns, Lae Dee Bugg, Snofolk, and more! Always more. What great fun it has been to look back at the last 2 1/2 years! It has me wondering just how much art will fill this computer by the end of 2013! I have some ideas right now!!!!

By: Alice,

on 12/26/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

gravity,

Mathematics,

newton,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

Émilie du Châtelet,

Science & Medicine,

ether,

Halley,

Mary Somerville,

Clairaut,

Huygens,

Leibniz,

Newtonian Revolution,

Principia,

Seduced by Logic,

newton’s,

Add a tag

By Robyn Arianrhod

This year, 2012, marks the 325th anniversary of the first publication of the legendary Principia (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), the 500-page book in which Sir Isaac Newton presented the world with his theory of gravity. It was the first comprehensive scientific theory in history, and it’s withstood the test of time over the past three centuries.

Unfortunately, this superb legacy is often overshadowed, not just by Einstein’s achievement but also by Newton’s own secret obsession with Biblical prophecies and alchemy. Given these preoccupations, it’s reasonable to wonder if he was quite the modern scientific guru his legend suggests, but personally I’m all for celebrating him as one of the greatest geniuses ever. Although his private obsessions were excessive even for the seventeenth century, he was well aware that in eschewing metaphysical, alchemical, and mystical speculation in his Principia, he was creating a new way of thinking about the fundamental principles underlying the natural world. To paraphrase Newton himself, he changed the emphasis from metaphysics and mechanism to experiment and mathematical analogy. His method has proved astonishingly fruitful, but initially it was quite controversial.

He had developed his theory of gravity to explain the cause of the mysterious motion of the planets through the sky: in a nutshell, he derived a formula for the force needed to keep a planet moving in its observed elliptical orbit, and he connected this force with everyday gravity through the experimentally derived mathematics of falling motion. Ironically (in hindsight), some of his greatest peers, like Leibniz and Huygens, dismissed the theory of gravity as “mystical” because it was “too mathematical.” As far as they were concerned, the law of gravity may have been brilliant, but it didn’t explain how an invisible gravitational force could reach all the way from the sun to the earth without any apparent material mechanism. Consequently, they favoured the mainstream Cartesian “theory”, which held that the universe was filled with an invisible substance called ether, whose material nature was completely unknown, but which somehow formed into great swirling whirlpools that physically dragged the planets in their orbits.

The only evidence for this vortex “theory” was the physical fact of planetary motion, but this fact alone could lead to any number of causal hypotheses. By contrast, Newton explained the mystery of planetary motion in terms of a known physical phenomenon, gravity; he didn’t need to postulate the existence of fanciful ethereal whirlpools. As for the question of how gravity itself worked, Newton recognized this was beyond his scope — a challenge for posterity — but he knew that for the task at hand (explaining why the planets move) “it is enough that gravity really exists and acts according to the laws that we have set forth and is sufficient to explain all the motions of the heavenly bodies…”

What’s more, he found a way of testing his theory by using his formula for gravitational force to make quantitative predictions. For instance, he realized that comets were not random, unpredictable phenomena (which the superstitious had feared as fiery warnings from God), but small celestial bodies following well-defined orbits like the planets. His friend Halley famously used the theory of gravity to predict the date of return of the comet now named after him. As it turned out, Halley’s prediction was fairly good, although Clairaut — working half a century later but just before the predicted return of Halley’s comet — used more sophisticated mathematics to apply Newton’s laws to make an even more accurate prediction.

Clairaut’s calculations illustrate the fact that despite the phenomenal depth and breadth of Principia, it took a further century of effort by scores of mathematicians and physicists to build on Newton’s work and to create modern “Newtonian” physics in the form we know it today. But Newton had created the blueprint for this science, and its novelty can be seen from the fact that some of his most capable peers missed the point. After all, he had begun the radical process of transforming “natural philosophy” into theoretical physics — a transformation from traditional qualitative philosophical speculation about possible causes of physical phenomena, to a quantitative study of experimentally observed physical effects. (From this experimental study, mathematical propositions are deduced and then made general by induction, as he explained in Principia.)

Even the secular nature of Newton’s work was controversial (and under apparent pressure from critics, he did add a brief mention of God in an appendix to later editions of Principia). Although Leibniz was a brilliant philosopher (and he was also the co-inventor, with Newton, of calculus), one of his stated reasons for believing in the ether rather than the Newtonian vacuum was that God would show his omnipotence by creating something, like the ether, rather than leaving vast amounts of nothing. (At the quantum level, perhaps his conclusion, if not his reasoning, was right.) He also invoked God to reject Newton’s inspired (and correct) argument that gravitational interactions between the various planets themselves would eventually cause noticeable distortions in their orbits around the sun; Leibniz claimed God would have had the foresight to give the planets perfect, unchanging perpetual motion. But he was on much firmer ground when he questioned Newton’s (reluctant) assumption of absolute rather than relative motion, although it would take Einstein to come up with a relativistic theory of gravity.

Einstein’s theory is even more accurate than Newton’s, especially on a cosmic scale, but within its own terms — that is, describing the workings of our solar system (including, nowadays, the motion of our own satellites) — Newton’s law of gravity is accurate to within one part in ten million. As for his method of making scientific theories, it was so profound that it underlies all the theoretical physics that has followed over the past three centuries. It’s amazing: one of the most religious, most mystical men of his age put his personal beliefs aside and created the quintessential blueprint for our modern way of doing science in the most objective, detached way possible. Einstein agreed; he wrote a moving tribute in the London Times in 1919, shortly after astronomers had provided the first experimental confirmation of his theory of general relativity:

“Let no-one suppose, however, that the mighty work of Newton can really be superseded by [relativity] or any other theory. His great and lucid ideas will retain their unique significance for all time as the foundation of our modern conceptual structure in the sphere of [theoretical physics].”

Robyn Arianrhod is an Honorary Research Associate in the School of Mathematical Sciences at Monash University. She is the author of Seduced by Logic: Émilie Du Châtelet, Mary Somerville and the Newtonian Revolution and Einstein’s Heroes. Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Celebrating Newton, 325 years after Principia appeared first on OUPblog.

By: sylvandellpublishing,

on 12/11/2012

Blog:

Sylvan Dell Publishing's Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Children's Books,

friendship,

picture books,

moose,

giraffe,

I Spy,

children's activities,

bat,

packrat,

Sylvan Dell Publishing,

magpie,

scavenger hunt,

habitat,

Newton,

Sylvan Dell Posts,

canine cancer,

friendship activities,

Add a tag

December is a time for friendship, and what better way to demonstrate friendship to children, than through a picture book? Here are a few of Sylvan Dell’s favorite books about friendship with fun and easy activities that you can do this holiday season.

Newton and Me – While at play with his dog, Newton, a young boy discovers the laws of force and motion in his everyday activities. Told in rhyme, Lynne Mayer’s Newton and Me follows these best friends on an adventure as they apply physics to throwing a ball, pulling a wagon, riding a bike, and much more. With the help of Sherry Rogers’ playful illustrations, children will learn that physics is a part of their world. They will realize that Newton’s Laws of Motion describe experiences they have every day, and they will recognize how forces affect the objects around them.

Newton and Me – While at play with his dog, Newton, a young boy discovers the laws of force and motion in his everyday activities. Told in rhyme, Lynne Mayer’s Newton and Me follows these best friends on an adventure as they apply physics to throwing a ball, pulling a wagon, riding a bike, and much more. With the help of Sherry Rogers’ playful illustrations, children will learn that physics is a part of their world. They will realize that Newton’s Laws of Motion describe experiences they have every day, and they will recognize how forces affect the objects around them.

Activity: Help you child get to know their friends. Start a conversation and learn about their family pet or favorite toy. Encourage your child to ask questions.

Moose and Magpie – It isn’t easy being a moose. You’re a full-grown adult at the age of one, and it itches like crazy when your antlers come in! In Bettina Restrepo’s Moose and Magpie, young Moose is lucky to find a friend and guide in the wisecracking Magpie. “What do the liberty bell and moose have in common?” the Magpie asks as the seasons begin to change. Then, when fall comes: “Why did the moose cross the road?” Vivid illustrations by Sherry Rogers bring these characters to life. Laugh along with Moose and Magpie, and maybe-just maybe-Moose will make a joke of his own!

Moose and Magpie – It isn’t easy being a moose. You’re a full-grown adult at the age of one, and it itches like crazy when your antlers come in! In Bettina Restrepo’s Moose and Magpie, young Moose is lucky to find a friend and guide in the wisecracking Magpie. “What do the liberty bell and moose have in common?” the Magpie asks as the seasons begin to change. Then, when fall comes: “Why did the moose cross the road?” Vivid illustrations by Sherry Rogers bring these characters to life. Laugh along with Moose and Magpie, and maybe-just maybe-Moose will make a joke of his own!

Activity: Comedy hour – give your child and friends a “microphone” and encourage them to tell jokes. Make sure they know not to tell jokes at their friend’s expense.

Home in the Cave – Baby Bat loves his cave home and never wants to leave it. While practicing flapping his wings one night, he falls, and Pluribus Packrat rescues him. They then explore the deepest, darkest corners of the cave where they meet amazing animals—animals that don’t need eyes to see or colors to hide from enemies. Baby Bat learns how important bats are to the cave habitat and how other cave-living critters rely on them for their food. Will Baby Bat finally venture out of the cave to help the other animals?

Home in the Cave – Baby Bat loves his cave home and never wants to leave it. While practicing flapping his wings one night, he falls, and Pluribus Packrat rescues him. They then explore the deepest, darkest corners of the cave where they meet amazing animals—animals that don’t need eyes to see or colors to hide from enemies. Baby Bat learns how important bats are to the cave habitat and how other cave-living critters rely on them for their food. Will Baby Bat finally venture out of the cave to help the other animals?

Activity: Prepare a winter scavenger hunt for your child and friends. They can go on an adventure together and the reward can be a cup of hot coco and talking about their fun adventures of the day.

Habitat Spy – Let’s spy on plants, insects, birds, and mammals in 13 different habitats. Told in rhyming narrative, Habitat Spy invites children to search for and find plants, invertebrates, birds, and mammals and more that live in 13 different habitats: backyard, beach, bog, cave, desert, forest, meadow, mountain, ocean, plains, pond, river, and cypress swamp. Children will spend hours looking for and counting all the different plants and animals while learning about what living things need to survive.

Habitat Spy – Let’s spy on plants, insects, birds, and mammals in 13 different habitats. Told in rhyming narrative, Habitat Spy invites children to search for and find plants, invertebrates, birds, and mammals and more that live in 13 different habitats: backyard, beach, bog, cave, desert, forest, meadow, mountain, ocean, plains, pond, river, and cypress swamp. Children will spend hours looking for and counting all the different plants and animals while learning about what living things need to survive.

Activity: While running those busy errands this season turn off the radio and play “I Spy” in the car while driving around town.

The Giraffe Who was Afraid of Heights – Imagine if the one thing that keeps you safe is what you fear the most. This enchanting story tells of a giraffe who suffers from the fear of heights. His parents worry about his safety and send him to the village doctor for treatment. Along the way, he befriends a monkey who is afraid of climbing trees and a hippo that is afraid of water. A life-threatening event causes the three friends to face and overcome each of their fears. The “For Creative Minds” section includes fun facts and animal adaptation information, a match-the-feet game and a mix-n-match activity.

The Giraffe Who was Afraid of Heights – Imagine if the one thing that keeps you safe is what you fear the most. This enchanting story tells of a giraffe who suffers from the fear of heights. His parents worry about his safety and send him to the village doctor for treatment. Along the way, he befriends a monkey who is afraid of climbing trees and a hippo that is afraid of water. A life-threatening event causes the three friends to face and overcome each of their fears. The “For Creative Minds” section includes fun facts and animal adaptation information, a match-the-feet game and a mix-n-match activity.

Activity: Sending out holiday cards? Help your child make a holiday card thanking their friends for their help and friendship throughout the year.

Champ’s Story: Dogs Get Cancer Too! – Children facing cancer—whether their own, a family member’s, a friend’s, or even a pet’s—will find help in understanding the disease through this book. A young boy discovers his dog’s lump, which is then diagnosed with those dreaded words: “It’s cancer.” The boy becomes a loving caretaker to his dog, who undergoes the same types of treatments and many of the same reactions as a human under similar circumstances (transference). Medical writer and award-winning children’s author, Sherry North artfully weaves the serious subject into an empathetic story that even young children can understand.

Champ’s Story: Dogs Get Cancer Too! – Children facing cancer—whether their own, a family member’s, a friend’s, or even a pet’s—will find help in understanding the disease through this book. A young boy discovers his dog’s lump, which is then diagnosed with those dreaded words: “It’s cancer.” The boy becomes a loving caretaker to his dog, who undergoes the same types of treatments and many of the same reactions as a human under similar circumstances (transference). Medical writer and award-winning children’s author, Sherry North artfully weaves the serious subject into an empathetic story that even young children can understand.

Activity: If a good friend is sick and children do not understand Champ’s Story is a great conversation starter. Give your child crayons and a piece of paper help them express their feelings through art.

These and many other fun books and lessons are available for the holidays at www.sylvandellpublishing.com.

By: Kirsty,

on 4/7/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

Environmental & Life Sciences,

charles taylor,

secularism,

creationist,

darwin the writer,

george levine,

human evolution,

darwin’s,

History,

Religion,

Science,

World,

biology,

atheist,

Charles Darwin,

controversial,

einstein,

Victorian,

evolution,

Darwin,

intelligent design,

secular,

newton,

Add a tag

By George Levine

How could Darwin still be controversial? We do not worry a lot about Isaac Newton, nor even about Albert Einstein, whose ideas have been among the powerful shapers of modern Western culture. Yet for many people, undisturbed by the law of gravity or by the theories of relativity that, I would venture, 99% of us don’t really understand, Darwin remains darkly threatening. One of the great figures in the history of Western thought, he was respectable and revered enough even in his own time to be buried in Westminster Abbey, of all places. He supported his local church; he was a Justice of the Peace; and he never was photographed as a working scientist, only as a gentleman and a family man. Yet a significant proportion of people in the English-speaking world vociferously do not “believe” in him.

Darwin is resisted not because he was wrong but because his ideas apply not only to the ants, and bees, and birds, and anthropoids, but to us. His theory is scary to many people because it seems to them it lessens our dignity and deprives our ethics of a foundation. The problem, of course, is that, like the theories of gravity and relativity, it is true.

At the heart of this very strange phenomenon there is a fundamental crisis of secularism. Secularism is not simply disbelief; it is not equivalent to atheism. Many supporters of secularism, like the distinguished Catholic philosopher, Charles Taylor, are believers. The most important aspect of secularism is that it is a condition of peaceful coexistence of otherwise antithetical faiths. In a secular state, diverse religions must agree that on matters of civil order and organization there is an institution to which they will all defer in what Taylor has described as “overlapping consensus.” They may disagree about God but they have to agree that in civil society they will adhere to the laws of the country.

But what happens when the overlapping consensus doesn’t overlap? This brings us to a very complicated problem: the authority of the specialist. In a democratic society, it is the responsibility of each of us to stay informed on issues that matter to the polity, and to make judgments, usually through established institutions, school boards, for example, or national elections. At the same time, our society usually sanctions the training of professionals, and forces them to undergo rigorous training, tests them to be sure of their qualifications.

Within professions, there will inevitably be learned and crucial squabbling and exploration, and new theories piled on top of old ones, or revising them. But these squabbles are part of what it is to be professional and they rarely reach the ears of the lay population. When science as an institution sanctions evolutionary theory (and squabbles about how it works), and its most distinguished practitioners insist that evolution is the foundation of all modern biology and by way of that theory make ever expanding discoveries about our health, a significant portion of the population accuse them of mere prejudice against doubters. People insist they don’t “believe” in Darwin, when they haven’t read him, don’t understand the theory to which they object, and seem unaware that evolutionary biology, though perhaps founded on Darwin, has long since made the nature of Darwin’s belief irrelevant to the validity of modern science.

Imagine a scientific community that allowed published papers to be reviewed by lay people, or simply published them without being reviewed by experts in the field. Imagine if The New England Journal of Medicine, or Nature, accepted papers which had not produced adequate evidence to make their cases, or distorted and misrepresented the evidence. Would that be a reasonable and democratic openi

.jpeg?picon=3304)

By: Leslie Ann Clark,

on 12/10/2010

Blog:

Leslie Ann Clark's Skye Blue Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

work,

fun,

coffee,

Just for fun,

art,

fabric,

snowman,

studio,

tween,

children's book,

bunny,

sketching,

funny,

photo shoot,

chicken,

dancing,

lamb,

cocoa,

Kicking Around Thoughts,

Family Matters... yeah it does...,

Work is Play....?,

Newton,

art with heart,

chickies,

keep on moving,

my world,

Add a tag

It has been busy busy busy in the studio! The place is jammed packed with characters waiting to be famous.

It has been busy busy busy in the studio! The place is jammed packed with characters waiting to be famous.

Newton has had his day in the sun with a new Baby Journal out in January.

“Yes You Can Man” wants a bit of the action for himself. He has been waiting in the wings with his REALLY BIG ideas!

Peep Squeak?.… he is always “On the Move!“. There will be Peepsqueak fabric out in February and a Peepsqueak‘s children’s book in the works for 2012..

Lae Dee Bugg is hoping for a July release at Christian Art Gifts for the TWEEN market.

Bitty Bot?… she and her bot friends really wants to be on fabric. They are waiting to hear back from a recent submission.

Hen Rietta fabric is in revision mode. Hen Rietta‘s friend, Grace is serving us up some hot cocoa. She is standing near ……. Shivery the snowman! Brrrrr!!! He has high hopes for a children’s book someday.

There is no forgetting Bea Bunny. She is always trying to get in the picture. She will debut in the Peepsqueak book.

This is life in my studio. Never a dull moment!

Oh NO! did you hear that? It’s Zippy! That little hedge hog came in late and missed the photo shoot. I will not hear the end of that!

“Zippy! Next time try to be on time. Remember, you snooze you lose!”

There are also bears, clowns, birds and more. It is never boring in the studio!

Filed under:

Family Matters... yeah it does...,

Just for fun,

Kicking Around Thoughts,

Work is Play....?

![]()

.jpeg?picon=3304)

By: Leslie Ann Clark,

on 10/20/2010

Blog:

Leslie Ann Clark's Skye Blue Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Newton,

day care,

Children,

kids,

Africa,

Just for fun,

frog,

t shirts,

babies,

South Africa,

baby clothes,

duck,

Add a tag

By: Kirsty,

on 8/3/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

UK,

einstein,

Science,

A-Featured,

energy,

scientists,

physics,

Early Bird,

physicists,

newton,

brook taylor,

erasmus darwin,

faraday,

henry cavendish,

Jennifer Coopersmith,

coopersmith,

lavoisier,

Add a tag

By Jennifer Coopersmith

There is a Jane Austen-esque phrase in my book: “it is a ceaseless wonder that our universal and objective science comes out of human – sometimes all too human – enquiry”. Physics is rather hard to blog, so I’ll write instead about the practitioners of science – what are they like? Are there certain personality types that do science? Does the science from different countries end up being different?

Without question there are fewer women physicists than men physicists and, also without question, this is a result of both nature and nurture. Does it really matter how much of the ‘blame’ should be apportioned to nature and how much to nurture? Societies have evolved the way they have for a reason, and they have evolved to have less women pursuing science than men (at present). Perhaps ‘intelligence’ has even been defined in terms of what men are good at?

Do a disproportionate number of physicists suffer from Asperger Syndrome (AS)? I deplore the fashion for retrospectively diagnosing the most famous physicists, such as Newton and Einstein, as suffering in this way. However, I’ll jump on the bandwagon and offer my own diagnosis: these two had a different ‘syndrome’ – they were geniuses, period. Contrary to common supposition, it would not be an asset for a scientist to have AS. Being single-minded and having an eye for detail – good, but having a narrow focus of interest and missing too much of the rich tapestry of social and worldly interactions – not good, and less likely to lead to great heights of creativity.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the science of energy was concentrated in two nations, England and France. The respective scientists had different characteristics. In England (strictly, Britain) the scientists were made up from an undue number of lone eccentrics, such as the rich Gentleman-scientists, carrying out researches in their own, privately–funded laboratories (e.g. Brook Taylor, Erasmus Darwin, Henry Cavendish and James Joule) and also religious non-conformists, of average or modest financial means (e.g. Newton, Dalton, Priestley and Faraday). This contrasts with France, where, post-revolution, the scientist was a salaried professional and worked on applied problems in the new state institutions (e.g. the French Institute and the École Polytechnique). The quality and number of names concentrated into one short period and one place (Paris), particularly in applied mathematics, has never been equalled: Lagrange, Laplace, Legendre, Lavoisier and Lamarck, – and these are only the L’s. As the historian of science, Henry Guerlac, remarked, science wasn’t merely a product of the French Revolution, it was the chief cultural expression of it.

There was another difference between the English and French scientists, as sloganized by the science historian Charles Gillispie: “the French…formulate things, and the English do them.” For example, Lavoisier developed a system of chemistry, including a new nomenclature, while James Watt designed and built the steam engine.

From the mid-19th century onwards German science took a more leading role and especially noteworthy was the rise of new universities and technical institutes. While many German scientists had religious affiliations (for example Clausius was a Lutheran), their science was neutral with regards to religion, and this was different to the trend in Britain. For example, Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) talked of the Earth “waxing old” and other quotes from the Bible, and, although he was not explicit, appears to have had religious objections to Darwin’s Theory of Evolution (at any rate, he wanted his ‘age of the Earth calculations’ to contradict Darwin’s Theory).

Whereas personal, cultural, social, economic and political factors will undoubtedly influence the course of science, the ultimate laws must be free of all such associations. Presumably the laws of Thermodynamics would still

Newton and Me – While at play with his dog, Newton, a young boy discovers the laws of force and motion in his everyday activities. Told in rhyme, Lynne Mayer’s Newton and Me follows these best friends on an adventure as they apply physics to throwing a ball, pulling a wagon, riding a bike, and much more. With the help of Sherry Rogers’ playful illustrations, children will learn that physics is a part of their world. They will realize that Newton’s Laws of Motion describe experiences they have every day, and they will recognize how forces affect the objects around them.

Newton and Me – While at play with his dog, Newton, a young boy discovers the laws of force and motion in his everyday activities. Told in rhyme, Lynne Mayer’s Newton and Me follows these best friends on an adventure as they apply physics to throwing a ball, pulling a wagon, riding a bike, and much more. With the help of Sherry Rogers’ playful illustrations, children will learn that physics is a part of their world. They will realize that Newton’s Laws of Motion describe experiences they have every day, and they will recognize how forces affect the objects around them. Moose and Magpie – It isn’t easy being a moose. You’re a full-grown adult at the age of one, and it itches like crazy when your antlers come in! In Bettina Restrepo’s Moose and Magpie, young Moose is lucky to find a friend and guide in the wisecracking Magpie. “What do the liberty bell and moose have in common?” the Magpie asks as the seasons begin to change. Then, when fall comes: “Why did the moose cross the road?” Vivid illustrations by Sherry Rogers bring these characters to life. Laugh along with Moose and Magpie, and maybe-just maybe-Moose will make a joke of his own!

Moose and Magpie – It isn’t easy being a moose. You’re a full-grown adult at the age of one, and it itches like crazy when your antlers come in! In Bettina Restrepo’s Moose and Magpie, young Moose is lucky to find a friend and guide in the wisecracking Magpie. “What do the liberty bell and moose have in common?” the Magpie asks as the seasons begin to change. Then, when fall comes: “Why did the moose cross the road?” Vivid illustrations by Sherry Rogers bring these characters to life. Laugh along with Moose and Magpie, and maybe-just maybe-Moose will make a joke of his own! Home in the Cave – Baby Bat loves his cave home and never wants to leave it. While practicing flapping his wings one night, he falls, and Pluribus Packrat rescues him. They then explore the deepest, darkest corners of the cave where they meet amazing animals—animals that don’t need eyes to see or colors to hide from enemies. Baby Bat learns how important bats are to the cave habitat and how other cave-living critters rely on them for their food. Will Baby Bat finally venture out of the cave to help the other animals?

Home in the Cave – Baby Bat loves his cave home and never wants to leave it. While practicing flapping his wings one night, he falls, and Pluribus Packrat rescues him. They then explore the deepest, darkest corners of the cave where they meet amazing animals—animals that don’t need eyes to see or colors to hide from enemies. Baby Bat learns how important bats are to the cave habitat and how other cave-living critters rely on them for their food. Will Baby Bat finally venture out of the cave to help the other animals? Habitat Spy – Let’s spy on plants, insects, birds, and mammals in 13 different habitats. Told in rhyming narrative, Habitat Spy invites children to search for and find plants, invertebrates, birds, and mammals and more that live in 13 different habitats: backyard, beach, bog, cave, desert, forest, meadow, mountain, ocean, plains, pond, river, and cypress swamp. Children will spend hours looking for and counting all the different plants and animals while learning about what living things need to survive.

Habitat Spy – Let’s spy on plants, insects, birds, and mammals in 13 different habitats. Told in rhyming narrative, Habitat Spy invites children to search for and find plants, invertebrates, birds, and mammals and more that live in 13 different habitats: backyard, beach, bog, cave, desert, forest, meadow, mountain, ocean, plains, pond, river, and cypress swamp. Children will spend hours looking for and counting all the different plants and animals while learning about what living things need to survive. The Giraffe Who was Afraid of Heights – Imagine if the one thing that keeps you safe is what you fear the most. This enchanting story tells of a giraffe who suffers from the fear of heights. His parents worry about his safety and send him to the village doctor for treatment. Along the way, he befriends a monkey who is afraid of climbing trees and a hippo that is afraid of water. A life-threatening event causes the three friends to face and overcome each of their fears. The “For Creative Minds” section includes fun facts and animal adaptation information, a match-the-feet game and a mix-n-match activity.

The Giraffe Who was Afraid of Heights – Imagine if the one thing that keeps you safe is what you fear the most. This enchanting story tells of a giraffe who suffers from the fear of heights. His parents worry about his safety and send him to the village doctor for treatment. Along the way, he befriends a monkey who is afraid of climbing trees and a hippo that is afraid of water. A life-threatening event causes the three friends to face and overcome each of their fears. The “For Creative Minds” section includes fun facts and animal adaptation information, a match-the-feet game and a mix-n-match activity. Champ’s Story: Dogs Get Cancer Too! – Children facing cancer—whether their own, a family member’s, a friend’s, or even a pet’s—will find help in understanding the disease through this book. A young boy discovers his dog’s lump, which is then diagnosed with those dreaded words: “It’s cancer.” The boy becomes a loving caretaker to his dog, who undergoes the same types of treatments and many of the same reactions as a human under similar circumstances (transference). Medical writer and award-winning children’s author, Sherry North artfully weaves the serious subject into an empathetic story that even young children can understand.

Champ’s Story: Dogs Get Cancer Too! – Children facing cancer—whether their own, a family member’s, a friend’s, or even a pet’s—will find help in understanding the disease through this book. A young boy discovers his dog’s lump, which is then diagnosed with those dreaded words: “It’s cancer.” The boy becomes a loving caretaker to his dog, who undergoes the same types of treatments and many of the same reactions as a human under similar circumstances (transference). Medical writer and award-winning children’s author, Sherry North artfully weaves the serious subject into an empathetic story that even young children can understand.

That’s so exciting Les! I could just eat those little cuties up. : )

thanks Rachelle…. and Peep Squeak thanks you too. :0)