new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Nicaragua, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 15 of 15

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Nicaragua in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Tonia Allen Gould,

on 11/24/2014

Blog:

Tonia Allen Gould's Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Finding Corte Magore,

cultural travel,

experiential travel,

Nicaragua,

poverty,

social good,

social causes,

Author Posts,

crowdfunding,

Add a tag

This week, I’m especially thankful – thankful I have a solid roof over my head and a home with windows and doors, and readily available food hand-picked from a market, proper medicine and supplies, running water and yes, definitely yes, flushing toilet facilities and a roll of paper always at an arm’s reach to me.

I’m equally thankful I’ve seen with my own eyes, through experiential and cultural travel, a part of the world along the Caribbean Coast, in developing Nicaragua – so now I know what it means to call myself truly fortunate.

I’m thankful for the opportunities, present and past, I’ve had bestowed upon me simply because I’m a red, white and blue, flag-waving American, and thankful to know I could, if I had to, live without surplus and modern conveniences, electricity and things that don’t really matter if it came down to instinctual survival. I am heartened and enlightened to know there are nations of people everywhere, especially in developing countries, that know far more about survival than many of us ever could. And, it is they that have much to show us on what that really means, and globally, we can each benefit from showcasing our cultural differences in a non-exploitative, educational way.

I’m thankful to know I can survive under dire circumstances because I’ve seen people, with my own eyes, who have literally nothing and yet maybe, in some ways, they have everything they could ever want and need, because they know how to live and thrive in some of the poorest conditions on the planet and still know what it means to be a part of a community and to love and support their families.

I’m thankful that I can now put my personal judgements and biases aside, because I’ve seen impoverished children, far more impoverished than I ever was growing up – living below the poverty line in Midwestern America. While many of the people I met may be lacking in opportunity, Nicaraguan children still smile and are happy, because they are each cared for by an entire village of people, and causes, who invest their hearts and souls into their wellbeing and care, despite economic conditions.

Mostly, I am thankful that I have stumbled upon the Finding Corte Magore project which has put me on a personal path to growth and the opportunity to work and mindshare with some of the smartest and caring people I can ever hope to know. I am thankful that we have “found” Corte Magore and that I have had the great pleasure of coming to know the Campbell family, and their beautiful, private island of Hog Cay, Nicaragua, and that I have personally earned their family’s trust and support in the Finding Corte Magore project. It’s a huge undertaking and I’m comforted to know, it will take our own village of incredible people, to raise this project to be everything it promises to be.

See you on Corte Magore!

The Finding Corte Magore Project

Coming Soon on Hog Cay, Nicaragua

Tonia Allen Gould

By:

Tonia Allen Gould,

on 11/17/2014

Blog:

Tonia Allen Gould's Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

central american,

horse carriage,

Lake Nicaragua,

Nicaragua,

Latin America,

tourists,

Author Posts,

The Finding Corte Magore Project,

grenada,

Add a tag

Day 1:

We woke-up in Managua, Nicaragua’s Capital. We had hoped to be on the future site of the Finding Corte Magore project today on Hog Cay, but our flight to Bluefields, Nicaragua cancelled due to a tropical depression that moved in. We took advantage of the rain delay and Team Finding Corte Magore hired a driver and we traversed our way to historical Grenada. We hit the streets and really got to be tourists on foot and from inside a horse carriage. The highlight of our day was spending time out on Lago Nicaragua and getting caught in the rain.

By: AlyssaB,

on 8/3/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Religion,

Politics,

minors,

Current Affairs,

guatemala,

Nicaragua,

El Salvador,

Central America,

Humanities,

illegal immigration,

Honduras,

*Featured,

undocumented,

border security,

God and Gangs in Central America,

Homies and Hermanos,

Robert Brenneman,

undocumented youth,

brenneman,

Add a tag

By Robert Brenneman

Both the President and Senate Republicans have recently weighed in on what to do about the “surge” in undocumented minors arriving at the US border. Many of these undocumented youth come from the northern countries of Central America: Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Embedded in most arguments about what ought to be done are assertions about what prompted these minors to set out in the first place and what will become of them if they stay. But many of these assumptions miss the mark and the truth is a lot more complicated than the sloganeering that characterizes much of the debate.

Myth #1: The increase in migrating minors came about as a result of the rise of gang violence in Central America.

Gang violence in Central America is real and it has touched the lives of far too many Central American youth and families. But the gangs have been a major feature of urban life since at least the late 1990s and there is little evidence to argue that gangs have increased in strength, size, or activity during the past three years. Meanwhile, the increase in migration of minors has been stratospheric. Undeniably, some of the youth heading north are escaping gang violence or threats from the gangs, but even the UN’s special report Children on the Run found, after conducting interviews with a scientific sample of detained youth, that just under a third of the youth mentioned the gangs as a factor contributing to their decision to leave. Most of the youth citing gangs were from El Salvador and Honduras.

Myth #2: Violence is spiraling out of control throughout Central America.

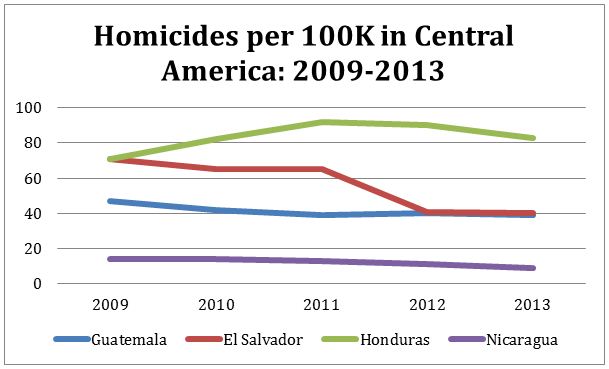

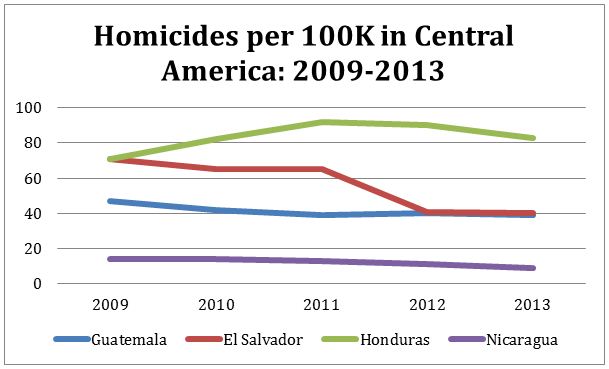

Although they share a number of important characteristics, the governments of Central America have taken different paths in how to relate to gangs, drugs, and violent crime. These divergent policies have contributed to very distinct outcomes. Notably, Nicaragua, which never took an “iron fist” approach to the gangs, has a far lower homicide rate and lower gang membership than its neighbors to the north. But even Guatemala, which has been well-known for homicidal violence ever since the state-sponsored violence of the 1980s, has shown improvement in its violent crime rate. Homicides have generally declined in recent years, probably as a partial result of Guatemala’s efforts to improve its justice system. As the chart below illustrates, Honduras has more than double the homicidal violence of its neighbors:

Myth #3: Coyotes (sometimes called “human traffickers”) are “tricking” children into migrating by telling them that they will receive citizenship upon arrival in the United States.

This myth reveals the utterly low regard in which many North Americans hold the intelligence of Central Americans. Oscar Martinez, an award-winning investigative journalist from El Salvador, recently published a fascinating account of his interview with a Salvadoran coyote who has been guiding his compatriots to El Norte since the 1970s. (Oscar knows about migrating minors — he has written a celebrated book about his trips across Mexico in the company of Central American migrants.) Among other myths effectively debunked in that interview is the notion that Central Americans hold wildly optimistic views about Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). In fact, most Central American youth and their relatives living in the United States are well aware that in all likelihood, they will, at best, become undocumented immigrants. But better to be close to family than suffer years of hardship while separated from parents, many of whom cannot travel “back” to their country of origin because of their own undocumented status. Of course, some of these youth are also escaping violence and the threat of violence as well as economic hardship and the crushing humiliation of living in generational poverty in some of the most unequal societies in the hemisphere. Thus, there are multiple factors at play when Central American youth (and their parents) consider whether or not to pay the US$7,000 charged by most coyotes for “guidance” across Mexico and over the US border. But few arrive under the illusion that they will attain legal status any time soon.

Myth #4: Central American youth who manage to stay in the United States as undocumented persons are likely to become part of a permanent underclass who represent a perpetual drain on the US economy.

Political conservatives often argue that our economy simply cannot sustain the weight of more undocumented Mexicans and Central Americans. In fact, research at the Pew Hispanic Center shows that 92% of undocumented men are active in the labor force (a higher proportion than among native men) and that most undocumented immigrants see modest improvements in their household income over time. Not surprisingly, those who eventually obtain legal status show far more substantial gains in their income and in the educational attainment of their children.

Myth #5: The situation in Central America is hopeless.

While it is true that many of the children who reach the US border have grown up in difficult and even dangerous situations and ought to be granted a hearing to determine whether or not they should be granted asylum, I have Central American friends (including some from Honduras) who might bristle at the suggestion that every child migrating northward is escaping life in hell itself. The idea that all Central American minors ought to be pronounced refugees upon arrival at the border rests on the mistaken assumption that these nations are hopelessly mired in violence and chaos, and it encourages the US government to throw in the towel with regard to advocating for economic and political improvements in the region.

True, a great deal of violence and hopelessness persists in the marginal urban neighborhoods of San Salvador and Tegucigalpa, but these communities did not evolve by accident. They are the result of years of under-investment in social priorities such as public education and public security compounded by the entrance in the late 1990s of a furious scramble among the cartels to establish and maintain drug movement and distribution networks across the isthmus in order to meet unflagging US demand. At the same time as we work to ensure that all migrant minors are treated humanely and with due process, we ought to use this moment to take a hard look at US foreign policy both past and present in order to build a robust aid package aimed at strengthening institutions and promoting more progressive tax policy so that these nations can promote human development, not just economic growth. It is time we take the long view with regard to our neighbors to the south.

Robert Brenneman is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Saint Michael’s College in Colchester, Vermont and the author of Homies and Hermanos: God and the Gangs in Central America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Five myths about the “surge” of Central American immigrant minors appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 7/8/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

american history,

America,

Nicaragua,

Latin America,

Dominican Republic,

haiti,

*Featured,

latin american history,

Alan McPherson,

The Invaded,

The Invaded: How Latin Americans and Their Allies Fought and Ended U.S. Occupations,

Latin American occupation,

república,

Add a tag

By Alan McPherson

Recent talk of declining US influence in the Middle East has emphasized the Obama administration’s diplomatic blunders. Its poor security in Benghazi, its failure to predict events in Egypt, its difficulty in reaching a deal on withdrawal in Afghanistan, and its powerlessness before sectarian violence in Iraq, to be sure, all are symptoms of this loss of influence.

Yet all miss a crucial point about a region of the world crawling with US troops. What makes a foreign military presence most unpopular is simply that it is, well, military. It is a point almost too obvious to make, but one that is forgotten again and again as the United States and other nations keep sending troops abroad and flying drones to take out those who violently oppose them.

The warnings against military occupation are age-old. The Founding Fathers understood the harshness of an occupying force, at least a British one, and thus declared in the Third Amendment that “no soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.”

US occupations of small Latin American countries a century ago taught a similar lesson. What was most irksome for those who saw the US marines occupy Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic between 1912 and 1934 was not the State Department’s desire to protect US lives and property. It also wasn’t its paranoia about German gunboats during World War I. It wasn’t even the fact itself of intervention. While some of these occupations began with minimal violence and a surprising welcome by occupied peoples, as months turned into years, the behavior of US troops on the ground became so brutal, so arbitrary, and so insensitive to local cultures that they drove many to join movements to drive the marines back into the sea.

Ocupación militar del 1916 en República Dominicana by Walter. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

It was one thing to subdue armed supporters of the regimes overthrown by the United States in all three countries. Latin Americans often met the demise of those unpopular governments with relief. Besides, armed groups recognized the overwhelming training and firepower of the marines and agreed readily to disarmament. As one Haitian palace guard recalled of the marine landing of 1915, “Everyone fled. Me too. You had only to see them, with their weaponry, their massive, menacing appearance, to understand both that they came to do harm to our country and that resistance was futile.”

It was the violence during “peace” time that turned the masses against occupation. At times marines and their native constabularies hunted small groups of insurgents and treated all locals as potential traitors. Other times they enforced new regulations, replaced local political officials, or militarized borders. And they could do it all with virtual impunity since any of their crimes would be tried by their own in US-run military provost courts.

Abuses were particularly frequent and grave either when no marines supervised constabularies or when a single marine — often a non-commissioned officer elevated to officer status in the constabulary — unleashed a reign of terror in a small town.

The residents of Borgne, in Haiti, for instance, hated a Lieutenant Kelly for approving beatings and imprisonments for trivial crimes or for no apparent reason at all. While in the Dominican Republic, around Hato Mayor, Captain Thad Taylor riled over his own fear-filled fiefdom. As one marine described it, Taylor “believed that all circumstances called for a campaign of frightfulness; he arrested indiscriminately upon suspicion; then people rotted in jail pending investigation or search for evidence.” In Nicaragua, the “M company” was widely accused of violence against children, especially throwing them into the air and spearing them with bayonets. In Haiti, a forced labor system known as the corvée saw Americans stop people, peasants, servants, or anyone else, in the street and make them work, particularly to build roads. The identification of the corvée with occupation abuse was so strong that, years later, Haitians gladly worked for foreign corporations but refused to build roads for them.

Rape added an element of gendered terror to abuses. The cases that appear in the historical record — many more likely went unreported — indicate an attitude of permissiveness, fed by the occupations’ monopoly of force, that bred widespread fear among occupied women. Assault was so dreaded that Haitian women stopped bathing in rivers.

Marines were none too careful about keeping abuses quiet and perhaps wanted them to be widely known so as to terrorize the populace. They repeatedly beat and hanged occupied peoples in town plazas, walked them down country roads with ropes around their necks, and ordered them to dig graves for others.

Brutality also marked the behavior of US troops in the cities, where there was no open rebellion. Often, marines and sailors grew bored and turned to narcotics, alcohol, and prostitution, vices that were sure to bring on trouble. A Navy captain suggested the humiliation suffered by Nicaraguan police, soldiers, and artisans, who all made less money than local prostitutes. He also noted the “racial feeling, . . . which leads to the assumption of an air of superiority on the part of the marines.” In response, the US minister requested that Nicaragua provide space for a canteen, dance hall, motion picture theatre, and other buildings to occupy the marines’ time.

Even the non-violent aspects of occupation were repressive. A French minister in Haiti noted that all Haitians resented intrusions in their daily freedoms, especially the curfew. Trigger-happy US soldiers on patrol also exhibited “an extraordinary lack of discipline and in certain cases, an incredible disdain for propriety.” Dominicans considered US citizens to be “hypocrites” because they drank so much abroad while living under prohibition at home. Reviewing such cases, a commanding officer assessed that 90 percent of his “troubles with the men” stemmed from alcohol. In a particularly terrifying incident, private Mike Brunski left his Port-au-Prince legation post at 6 a.m. and started shooting Haitians “apparently without provocation,” killing one and wounding others. He walked back to the legation “and continued his random firing from the balcony.” Medical examiners pronounced Brunski “sane but drunk.”

Abuse proved a recruiting bonanza for insurgents. Little useful information, and even less military advance, was gained from abuse and torture in Nicaragua. A Haitian group also admitted that “internal peace could not be preserved because the permanent and brutal violation of individual rights of Haitian citizens was a perpetual provocation to revolt.” Terror otherwise hardened the population against the occupation. Many in the Dominican Republic later testified with disgust to having seen lynchings with their own eyes. There and in Haiti, newspaper editors braved prison sentences to publish tales of atrocities.

By 1928, the State Department’s Sumner Welles observed that occupation “inevitably loses for the United States infinitely more, through the continental hostility which it provokes, through the fears and suspicions which it engenders, through the lasting resentment on the part of those who are personally injured by the occupying force, than it ever gains for the United States through the temporary enforcement of an artificial peace.”

Hostile, troublesome, horrifying: the US military in Latin America encountered a range of accusations as they it on believing that it brought security and prosperity to the region. Sound familiar? The lessons of Latin American resistance a century ago are especially relevant today, when counterinsurgency doctrine posits that a successful occupation, such as the one by coalition forces in Afghanistan, must win over local public opinion in order to bring lasting security. Thankfully, it appears that the lesson has sunk in to a certain extent, with diplomats increasingly reclaiming their role from the military as go-betweens with locals. Yet much of the damage has been done, and in the case of drones, no amount of diplomacy can assuage the feeling of terror felt throughout the countryside of Afghanistan and Pakistan when that ominous buzzing sound approaches overhead. It is, perhaps for better and certainly for worse, the new face of US military occupation.

Alan McPherson is a professor of international and area studies at the University of Oklahoma and the author of The Invaded: How Latin Americans and their Allies Fought and Ended US Occupations.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The trouble with military occupations: lessons from Latin America appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 5/16/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Central American civil wars,

Group Material,

Harry Mattison,

Marta Bautis,

Mel Rosenthal,

Susan Meiselas,

mattison,

History,

photography,

America,

Nicaragua,

social change,

Latin America,

salvador,

El Salvador,

*Featured,

Art & Architecture,

Arts & Leisure,

Online products,

Add a tag

By Erina Duganne

Many hope, even count on, photography to function as an agent of social change. In his 1998 book, Photojournalism and Foreign Policy: Icons of Outrage in International Crises, communications scholar David Perlmutter argues, however, that while photographs “may stir controversy, accolades, and emotion,” they “achieve absolutely nothing.”

In my current research project, I examine the difficult question of what contribution photography has made to social change through an examination of images documenting events from the Central American civil wars — El Salvador and Nicaragua, more specifically — that circulated in the United States in the 1980s. Rather than measure the influence of these photographs in terms of narrowly conceived causal relationships concerning issues of policy, I argue that to understand what these images did and did not achieve, they need to be situated in terms of their broader social, political, and cultural effects — effects that varied according to the ever shifting relations of their ongoing reproduction and reception. Below are three platforms across which photographs from the wars in Central America circulated and recirculated in the United States in the 1980s.

(1) In the early 1980s, the US government adopted a dual policy of military support in Central America. In El Salvador, they provided aid against the guerilla forces or FMLN while in Nicaragua they backed the contra war against the Sandinistas. Many Americans learned and formulated opinions about these policies through photographs that circulated in the news media. The cover of the 22 March 1982 issue of Time, for instance, featured a photograph of a gunship flying over El Salvador. Taken by US photojournalist Harry Mattison, the editors at Time used the photograph as part of their cover story questioning the use by the US government of aerial reconnaissance photographs of military installations in Nicaragua to establish a causal link between the leftist insurgents in El Salvador and Communist governments worldwide.

(2) In addition to these reconnaissance photographs, the Reagan administration also turned to photography in an eight-page State Department white paper entitled Communist Interference in El Salvador, which was released to the American public on 23 February 1981. In this white paper, the US government included two sets of military intelligence photographs of captured weapons, which they believed would help them to further provide the American public with “irrefutable proof” of Communist involvement via Russia and Cuba in Central America, and thereby justify the escalation of US military and economic aid to the supposedly moderate Salvadoran government. The aforementioned article in Time also questioned the validity of the sources used in this document.

(3) While photography played a prominent role in debates over the existence of a communist threat in Central America, beginning in 1983, a number of artists and photographers — Harry Mattison, Susan Meiselas, Group Material, Marta Bautis, Mel Rosenthal, among others — put photographs from the Central American conflicts, some of which had circulated directly in the aforementioned contexts and others which had not, to a different use. Rather than employ photographs to perpetuate or even question the accuracy of communist aggression in the region, these artists and photographers instead used the medium to examine the imperialist underpinning of the Reagan administration’s foreign policy in Central America as well as the longstanding geopolitical and historical implications of US involvement there. To this end, they produced the following: the 1983 photography book and exhibition El Salvador: Work of Thirty Photographers, which was edited by Harry Mattison, Susan Meiselas, and Fae Rubenstein and toured various US cities in 1984 and 1985; Group Material’s 1984 multi-media installation Timeline: A Chronicle of US Intervention in Central and Latin America, on view at the P.S. Contemporary Art Center in Queens, New York, as part of the ad hoc protest organization Artists Call Against US Intervention in Central America; and the exhibition The Nicaragua Media Project that toured various US cities in 1984 and 1985. Together these three photography books and art exhibitions provided, what I call, a “living” history for photographs from the Central American civil wars.

In his 1978 essay “Uses of Photography” that was anthologized in his 1980 book About Looking, cultural critic John Berger argues that for photographs to “exist in time,” they need to be placed in the “context of experience, social experience, social memory.” Using Berger’s definition of a “living” history as a model, my research project offers a novel way to think about how, within the contexts of these exhibitions and books, photographs from the conflicts in El Salvador and Nicaragua functioned as dynamic, even affective objects, whose mobility and mutability could empower contemporary viewers to look beyond the so-called communist threat in the region that was perpetuated through the Reagan administration as well as the news media and begin to think more carefully about past histories of US imperialism and global human oppression in Central America.

Erina Duganne is Associate Professor of Art History at Texas State University where she teaches courses in American art, photography, and visual culture. She is the author of The Self in Black and White: Race and Subjectivity in Postwar American Photography (2010) as well as a co-editor and an essayist for Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain (2007). She has also written about her current research project for the blog In the Darkroom.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Photography and social change in the Central American civil wars appeared first on OUPblog.

By:

Tonia Allen Gould,

on 5/15/2014

Blog:

Tonia Allen Gould's Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Social Entrepreneurialism,

picture books,

Island,

Nicaragua,

Humanity,

Augmented Reality,

Gamification,

Author Posts,

Literacy Rate,

Tonia Allen Gould,

Samuel. T. Moore of Corte Magore,

Add a tag

Children’s picture book author, Tonia Allen Gould, wants to crowd-fund an island to bring awareness to the children of Nicaragua who drop out of school, on average, by the sixth grade.

The Finding Corte Magore Project works virtually to connect a global community of students and crowd funders in real time with the plight of educationally and economically repressed Nicaragua. The project incorporates social entrepreneurialism, gamification, and augmented reality and involves showcasing, purchasing and managing, through collective voting processes, one of the country’s own small, yet beautiful islands to create awareness, coupled with sustainable, positive and long-term impact on the country’s people.

Samuel T. Moore of Corte Magore Original Musical Score by Robby Armstrong, Copyright (C) Tonia Allen Gould, All Rights Reserved.

By: Grant Overstake,

on 7/26/2013

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Chile,

Uncategorized,

Canada,

Japan,

Taiwan,

Amazon,

Philippines,

Mexico,

France,

Australia,

India,

Poland,

Germany,

New Zealand,

Pakistan,

Puerto Rico,

Belgium,

Spain,

Slovenia,

United Kingdom,

Finland,

South Africa,

Brazil,

Singapore,

Nicaragua,

Ireland,

Netherlands,

Italy,

Turkey,

Israel,

Switzerland,

Nigeria,

Sweden,

Indonesia,

Mongolia,

Thailand,

Argentina,

Morocco,

Peru,

Jamaica,

Norway,

Egypt,

Indiebound,

Iceland,

Venezuela,

Bahamas,

Denmark,

Greece,

United States,

Portugal,

Czech Republic,

Colombia,

Romania,

Croatia,

Saudi Arabia,

Hong Kong,

Ukraine,

Jordan,

Yemen,

Algeria,

Hungary,

Bermuda,

Ecuador,

Bulgaria,

Estonia,

Tunisia,

Trinidad and Tobago,

Girls Sports,

Bahrain,

Lithuania,

Namibia,

United Arab Emirates,

Grant Overstake,

Inspirational Sports Stories,

Maggie Vaults Over the Moon,

young adult sports,

KSHSAA,

Pole Vault Fiction,

Track and Field Stories,

sports novels,

Recommended sports books for teens,

Watermark Books and Cafe,

Kansas State High School Activities Association Journal,

Austria Botswana,

Insirational Sports Books,

Isle of Man,

Republic of Korea,

Russian Federation,

Add a tag

Maggie Steele, the storybook heroine who vaults over the moon, has been attracting thousands of visitors from around the world. So many visitors, in fact, that she’s using a time zone map to keep track of them all.* People are … Continue reading →

By: Alice,

on 1/23/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Affairs,

Nicaragua,

walmart,

farmers,

supermarket,

supermarkets,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Business & Economics,

American Journal of Agricultural Economics,

Hope Michelson,

NGOs,

small farmer,

Add a tag

By Hope Michelson

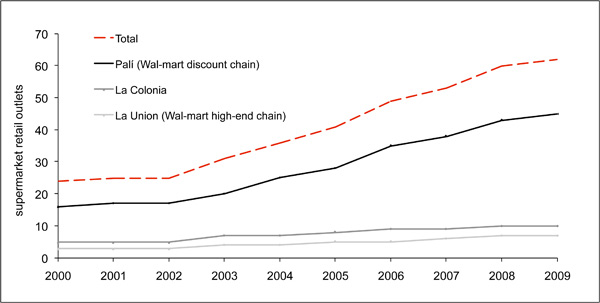

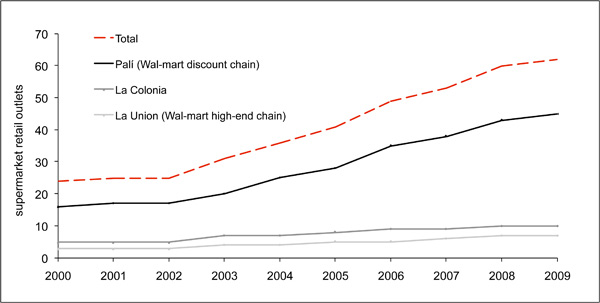

Walmart now has stores in more than fifteen developing countries in Central and South America, Asia and Africa. A glimpse at the scale of operations: Nicaragua, with a population of approximately six million, currently has 78 Walmart retail outlets with more on the way. That’s one store for every 75,000 Nicaraguans; in the United States there’s a Walmart store for every 69,000 people. The growth has been rapid; in the last seven years, the corporation has more than doubled the number of stores in Nicaragua (see accompanying graphs — Figure 1 from the paper).

When a supermarket chain like Walmart moves into a developing country it requires a steady supply of fresh fruits and vegetables largely sourced domestically. In developing countries where the majority of the poor rely on agriculture for their livelihood, this means that poor farmers are increasingly selling produce to and contracting directly with large corporations. In precisely this way, Walmart has begun to transform the domestic agricultural markets in Nicaragua over the past decade. This profound change has been met with both excitement and trepidation by governments and development organizations because the likely effects on poverty and inequality are not known, in particular:

- What existing assets or experience are required for a farmer to sell their produce to supermarkets?

- Do small farmers who sell their produce to supermarkets benefit from the relationship?

- What is the role of NGOs in facilitating small farmer relationships with supermarkets?

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets.

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets.

Generally, researchers have studied the inclusion of farmers in supply chains by measuring the income, assets and welfare of a group of farmers selling a crop to supermarkets (“suppliers”) with a similar group of farmers selling the same crop in traditional markets (“non-suppliers”). This research has provided important insights but has struggled with two persistent challenges.

First, because most existing studies rely on surveys of farmers living in the same area, we do not know how important farmer experience or assets such as farm machinery or irrigation, are for inclusion in supply chains in comparison to other farmer characteristics like community access to water or proximity to good roads.

Second, without measurements on supplier and non-supplier farmers over time it is difficult for a researcher to isolate the effect being a supplier has on the farmer. For example, if Walmart excels at choosing higher-ability farmers as suppliers, a study that just compared supplier and non-supplier incomes would overestimate the supermarket effect because Walmart’s high-ability farmers would earn more income even if they had not contracted with the supermarket.

With these two challenges in mind, I implemented a research project in Nicaragua in which I first identified all small farmers who had had a steady supply relationship with supermarkets for at least one year since 2000 (see accompanying graphs — Figure 2 from the paper). I also revisited 400 farmers not supplying supermarkets but living in areas where supermarkets were buying produce. My team and I surveyed farmers about their experiences over the past eight years: the markets where they had sold, the farming, land, and household assets they had owned. Since my study included farmers selling a variety of crops to supermarkets and measured how their assets, and supermarket relationships, changed in time, I was able to more rigorously address how these markets affected small farmers. The project was part of a collaboration between researchers Michigan State University, Cornell University, and the Nitlapan Institute in Managua.

Results

Farmer participation

Farmers located close to the primary road network and Nicaragua’s capital, Managua, where the major sorting and packing facility is located, and with conditions that allow them to farm year round were much more likely to be suppliers. Remarkably, this effect was much stronger than other farmer characteristics such as existing farm capital or experience.

Farmer welfare

Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.

Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.

One way to think of income is as a flow of financial resources based, in part, on a farmer’s assets. By statistically relating a change in assets to a change in income I find that a 16% increase in assets corresponds to an average increase in annual household income of about $200 — or 15% of the average 2007 income for the farmers I studied.

Our previous work discovered that supermarkets don’t pay farmers a higher mean price than traditional markets but they do offer a more stable price. This analysis suggests a reason that household assets – and thus income — increase among farmers who sell to supermarkets; shielded from price fluctuations in the traditional markets by the supermarket contract, farmers invest in agriculture, in some cases moving to year-round cultivation. Farmers finance these investments through higher and more stable incomes and new credit sources. Income increases are attributable not to higher average prices but likely to increased production quantities.

NGOs

NGOs have played an important role in small farmer access to supermarket supply chains all over the world. In Nicaragua, a USAID program funded NGOs to help small farmers sell to supermarkets. These NGOs established farmers’ cooperatives and provided technical assistance, contract negotiation, and financing. Do NGOs change farmer selection or outcomes? Do they choose farmers with less wealth or experience? Or do farmers working with NGOs benefit in a special way from supermarkets because of the services NGOs provide?

We find, on average, that NGO-assisted farmers start with similar productive assets and land as those who sell to supermarkets without NGO assistance. Nor do we find a special effect on the assets of NGO-assisted farmers. However, we do find that NGOs play a critical role in keeping farmers with little previous experience in vegetable production in the supply chain. Low-experience farmers who are not assisted by NGOs are more likely to drop out of the supply chain than those assisted by NGOs.

Conclusions

These findings offer grounds for optimism and also a measure of caution with respect to the effects of supermarkets operating in developing countries. Supermarket contracts improve farmer welfare, and the improvements are detectable in farmers’ assets. However, since being close to roads and having the ability to farm year round is so critical to inclusion in the supply chain, not all farmers will be afforded these opportunities. Moreover, because these trends are still nascent in Nicaragua and in many other parts of the developing world, it remains to be seen what the broader effects will be for the agricultural sector and development. For example, as NGOs invest in preparing more small farmers to supply supermarkets, the gains to farmers from joining supply chains may be lost to increased competition. Our results in Nicaragua suggest that, given the small number of supplier farmers, changes in rural poverty related to supermarket expansion will be modest, but how will these supply chains, and the benefits they represent for farmers, change over time? I am currently a part of a team studying Walmart supply chains in China, which will interrogate these questions on a much larger scale in the context of a global and rapidly expanding economy.

Hope Michelson is a postdoctoral fellow at Columbia University’s Earth Institute in the Tropical Agriculture and Rural Environment program. She completed her doctoral research in the Economics of Development in 2010 at Cornell University’s Department of Applied Economics. She is the author of “Small Farmers, NGOs, and a Walmart World: Welfare Effects of Supermarkets Operating in Nicaragua” in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, which is available to read for free for a limited time.

The American Journal of Agricultural Economics provides a forum for creative and scholarly work on the economics of agriculture and food, natural resources and the environment, and rural and community development throughout the world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: All images property of Hope Michelson. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post What happens when Walmart comes to Nicaragua? appeared first on OUPblog.

I didn't intend to disappear from this blog for quite as long as I did, but I got busy with work on the manuscript of Best American Fantasy 3 (the contents of which we'll finally be able to announce next week!) and I've been teaching an online course for Plymouth State University, an interesting experience, since I've never taught classes entirely online before (nor am I all that sure it's a way I like teaching, but that's another story...)

I probably owe you an email.*

Readercon is coming up -- July 9-12. I'll be there Friday afternoon and most of Saturday. The great and glorious Liz Hand and Greer Gilman are guests of honor. The other guests ain't too shabby neither. Except for that Cheney guy. He's a putz.

Some things I've noticed out on the internets:

- Hal Duncan wrote a little post at his blog about ethics, reviewing, criticism, etc. A few people commented. Hal wrote another little post responding in particular to comments by Abigail Nussbaum and me. Then another related post on "The Absence of the Abject". And then two posts on "The Assumption of Authority" (one, two). They're wonderfully provocative and wide-ranging essays, but as the whole is now over 20,000 words long, I haven't been able to keep up with it. But I shall return to it over the course of the summer...

- Jeff VanderMeer has been working for what sounds to me like one of the coolest teen camps in the world, Shared Worlds, and as part of that asked a bunch of writers and other creative-type people, "What’s your pick for the top real-life fantasy or science fiction city?"

- I accompanied Eric Schaller and family to a magnificent concert by David Byrne a few weeks ago. Byrne's earnest dorkiness has been a balm to my soul since I was a kid. He's been on The Colbert Report a couple of times in support of his tour -- here, performing one of my favorite of his new songs, "Life is Long", and here performing "One Fine Day" (in which everybody seems a bit tired). The Colbert studio isn't quite Radio City Music Hall, but still...

- Tor.com has, in less than a year, become one of the best science fiction sites, and they've now launched a store that includes "special picks" from their great array of bloggers. (And, interestingly, though the site is allied with Tor Books, it's striven to be, as they say, "publisher agnostic", so it's not just about Tor's books.)

- Speaking of major SF sites, I enjoyed Charlie Jane Anders's post at io9 titled "4 Authors We Wish Would Return to Science Fiction" because it includes new comments from each of the four writers discussed: Mary Doria Russell, Nicola Griffith, Karen Joy Fowler, and Samuel R. Delany.

- I really loved Jeff Ford's post on the books he survived in primary and secondary school English classes.

- I seem to have written yet another Strange Horizons column.

Meanwhile, I've been reading a bunch of books I haven't written about. Some just for fun -- I went on a bit of an alternative history kick, reading

C.C. Finlay's The Patriot Witch

(available as an authorized PDF download

here) and L. Sprague de Camp's

Lest Darkness Fall.

The Patriot Witch attracted me because I've read some of Charlie Finlay's short stories and enjoyed them, and the book is set during the American Revolution, a time period about which I will read almost anything. The fantasy elements seemed a bit bland to me, but the scenes of the battles of Lexington and Concord were well done, reminding me of Howard Fast's

April Morning

, a book that, along with

Johnny Tremain

, was a favorite of mine when I was young. I'll probably read the next book in the "Traitor to the Crown" series because now I'm curious to see if the fantasy element develops in less familiar ways.

Lest Darkness Fall is, as many people through the decades have said, great fun, a kind of

Connectic Yankee for readers who want their protagonists to be endlessly resourceful, optimistic, and lucky.

Somewhere in there, I also fit in Jack Vance's

Emphyrio

, an engaging example of a certain sort of classic ethnographic science fiction, something halfway between

Lloyd Biggle and

Ursula Le Guin.

I did a bunch of that fun, light reading because on the side I've been delving deeply into various books about British and American colonialism and imperialism for a story I keep telling myself I'm going to write: a steampunk alternate history about a mad scientist, a U.S. and British fight over Nicaragua at the beginning of the 20th century, and the atrocities it all leads to. Among the various books I've been dipping into for my researches are

Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction

by John Rieder,

The Tools of Empire: Technology and European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century

by Daniel Headrick,

The Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History since 1900

by David Edgerton,

Confronting the American Dream: Nicaragua under U.S. Imperial Rule

by Michel Gobat,

The Eclipse of Great Britain: The United States and British Imperial Decline, 1895-1956

by Anne Orde,

The Sleep of Reason: Fantasy and Reality from the Victorian Age to the First World War

by Derek Jarrett,

Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest

by Anne McClintock, as well as such books of their time as Winston Churchill's

My African Journey

(pointed out to me by Njihia Mbitiru, who's been a big help in goading me on to write this story that I keep talking about) and

The Ethiopian: A Narrative of the Society of Human Leopards. Also a couple of books I've been familiar with for a while,

Histories of the Hanged: The Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire

by David Anderson and

Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain's Gulag in Kenya

by Caroline Elkins.

Clearly, I don't want to write a story -- I want to write an annotated bibliography!

Now, though, it's time to stop procrastinating and get back to work...

*Speaking of email, I've severely neglected the email address once associated with this blog (themumpsimus at gmail) because it became massively overloaded with spam (partly because I had redirected some ancient addresses at it) and sometime at the beginning of this year I made a resolution to clean it out, find real messages I'd missed, etc. I removed the link to it from this site so that people wouldn't inadvertently use it, but I expected to get it back up and working within a week. Then I kind of kept procrastinating. Every time I thought about it I suffered trauma. Now cleaning out and organizing the inbox is such a Herculean task that I may just give up and start over with a new, clean address. I don't know. I will fight through my anxieties and figure it out soon, though.

With every passing of Memorial Day, Chicanos, mexicanos, green-card holders and immigrant Latinos enter the U.S.'s military with hopes for acceptance by American society, driven by their newly adopted patriotism, and with aspirations to grub-stake their own American dream. Unfortunately, along with this comes our sometimes even naïve complicity to use the weapons of war on innocent civilians who are too often dark-skinned peoples not unlike us.

I read a piece this week that affected and impressed me such that I asked and received permission from TomDispatch.com to share parts of it with La Bloga readers. Two weekends after Memorial Day, seems a fitting time to post the following, adapted by Chris Hedges from his just released Collateral Damage: America's War Against Iraqi Civilians (Nation Books),

co-authored with Laila al-Arian. (Hedges is former Middle East Bureau Chief of the New York Times, a Pulitzer Prize winner, and a Senior Fellow at the Nation Institute.)

co-authored with Laila al-Arian. (Hedges is former Middle East Bureau Chief of the New York Times, a Pulitzer Prize winner, and a Senior Fellow at the Nation Institute.)

What impressed me most was not only Hedges' strikingly insightful and brutally compassionate analysis of what the Iraq War has done to American soldiers and Iraqi citizens, but more the words of Camilo Mejía, who became the first American veteran of this war to refuse service. (Mejía, originally from Nicaragua, became a permanent resident. In 1995, at age 19, he joined the Army and served nearly 9 years. In 2003 he was sent to Iraq. Mejía applied for a conscientious objector discharge after five months in Iraq, was charged with desertion, and served nine months before being released.)

You may not agree with the views expressed in my opening paragraph, and I am reviewing neither Hedges' nor Mejía's books for you here. You can do that for yourself for the reasons Hedges expresses in his last sentence below. Go here to read Hedges' entire piece or find out more about his book, as well as here to learn more about Mejía and his memoir, Road from ar Ramadi: The Private Rebellion of Staff Sergeant Camilo Mejía. And if you choose, let us know your thoughts. My own thoughts became confused as I read. I couldn't keep from hearing parallels between the attitudes and treatment of the Iraqi people there, and we and our brethren here in the U.S. But maybe that's just me.

Collateral Damage by Chris Hedges [excerpts]

Sgt. Camilo Mejía, who eventually applied while still on active duty to become a conscientious objector, said the ugly side of American racism and chauvinism appeared the moment his unit arrived in the Middle East. Fellow soldiers instantly ridiculed Arab-style toilets because they would be "sh-tting like dogs." The troops around him treated Iraqis, whose language they did not speak and whose culture was alien, little better than animals.

The word "haji" swiftly became a slur to refer to Iraqis, in much the same way "gook" was used to debase the Vietnamese and "raghead" is used to belittle those in Afghanistan. [Bloga note: haji is an honorific for those who make the pilgrimage to Mecca.] Soon those around him ridiculed "haji food," "haji homes," and "haji music."

Bewildered prisoners, who were rounded up in useless and indiscriminate raids, were stripped naked and left to stand terrified for hours in the baking sun. They were subjected to a steady torrent of verbal and physical abuse. "I experienced horrible confusion," Mejía remembered, "not knowing whether I was more afraid for the detainees or for what would happen to me if I did anything to help them."

These scenes of abuse, which began immediately after the American invasion, were little more than collective acts of sadism. Mejía watched, not daring to intervene yet increasingly disgusted at the treatment of Iraqi civilians. He saw how the callous and unchecked abuse of power first led to alienation among Iraqis and spawned a raw hatred of the occupation forces. When Army units raided homes, the soldiers burst in on frightened families, forced them to huddle in the corners at gunpoint, and helped themselves to food and items in the house.

"After we arrested drivers," he recalled, "we would choose whichever vehicles we liked, fuel them from confiscated jerry cans, and conduct undercover presence patrols in the impounded cars.

"But to this day I cannot find a single good answer as to why I stood by idly during the abuse of those prisoners except, of course, my own cowardice," he also noted.

Iraqi families were routinely fired upon for getting too close to checkpoints, including an incident where an unarmed father driving a car was decapitated by a .50-caliber machine gun in front of his small son. Soldiers shot holes into cans of gasoline being sold alongside the road and then tossed incendiary grenades into the pools to set them ablaze.

"It's fun to shoot sh-t up," a soldier said. Some opened fire on small children throwing rocks. And when improvised explosive devices (IEDS) went off, the troops fired wildly into densely populated neighborhoods, leaving behind innocent victims who became, in the callous language of war, "collateral damage."

"We would drive on the wrong side of the highway to reduce the risk of being hit by an IED," Mejía said of the deadly roadside bombs. "This forced oncoming vehicles to move to one side of the road and considerably slowed down the flow of traffic. In order to avoid being held up in traffic jams, where someone could roll a grenade under our trucks, we would simply drive up on sidewalks, running over garbage cans and even hitting civilian vehicles to push them out of the way. Many of the soldiers would laugh and shriek at these tactics."

At one point the unit was surrounded by an angry crowd protesting the occupation. Mejía and his squad opened fire on an Iraqi holding a grenade, riddling the man's body with bullets. Mejía checked his clip afterward and determined that he had fired 11 rounds into the young man. Units, he said, nonchalantly opened fire in crowded neighborhoods with heavy M-240 Bravo machine guns, AT-4 launchers, and Mark 19s, a machine gun that spits out grenades.

"The frustration that resulted from our inability to get back at those who were attacking us," Mejía said, "led to tactics that seemed designed simply to punish the local population that was supporting them."

* * *

Mejía said, regarding the deaths of Iraqis at checkpoints, "This sort of killing of civilians has long ceased to arouse much interest or even comment."

Mejía also watched soldiers from his unit abuse the corpses of Iraqi dead. He related how, in one incident, soldiers laughed as an Iraqi corpse fell from the back of a truck. "Take a picture of me and this motherf---er," said one of the soldiers who had been in Mejía's squad in Third Platoon, putting his arm around the corpse.

The shroud fell away from the body, revealing a young man wearing only his pants. There was a bullet hole in his chest.

"Damn, they really f---ed you up, didn't they?" the soldier laughed.

The scene, Mejía noted, was witnessed by the dead man's brothers and cousins.

The senior officers, protected in heavily fortified compounds, rarely experienced combat. They sent their troops on futile missions in the quest to be awarded Combat Infantry Badges. This recognition, Mejía noted, "was essential to their further progress up the officer ranks."

This pattern meant that "very few high-ranking officers actually got out into the action, and lower-ranking officers were afraid to contradict them when they were wrong." When the badges -- bearing an emblem of a musket with the hammer dropped, resting on top of an oak wreath -- were finally awarded, the commanders brought in Iraqi tailors to sew the badges on the left breast pockets of their desert combat uniforms.

"This was one occasion when our leaders led from the front," Mejía noted bitterly. "They were among the first to visit the tailors to get their little patches of glory sewn next to their hearts."

[Final thoughts from author Hedges]

"Prophets are not those who speak of piety and duty from pulpits -- few people in pulpits have much worth listening to -- but are the battered wrecks of men and women who return from Iraq and speak the halting words we do not want to hear, words that we must listen to and heed to know ourselves. They tell us war is a soulless void. They have seen and tasted how war plunges us into perversion, trauma, and an unchecked orgy of death. And it is their testimonies that have the redemptive power to save us from ourselves." (© 2008 Chris Hedges)

Rudy Ch. Garcia

Richard Nash at Soft Skull saw my mention of Alex Cox's movie Walker and sent on a brief passage from Cox's upcoming book X-Films: True Confessions of a Radical Filmmaker , which Soft Skull/Counterpoint will be bringing out in a few months. Thanks to Richard for giving me permission to share this:

, which Soft Skull/Counterpoint will be bringing out in a few months. Thanks to Richard for giving me permission to share this:

Walker is my best, my most expensive, and my least-seen film. It’s the bio-pic of William Walker -- an American mercenary who had himself made president of Nicaragua in the mid-19th century. In the US, Walker was an anti-slavery liberal; in Nicaragua he instituted slavery. He’s almost unknown in the US today, but in the 1850’s Walker was fantastically popular. The newspapers wrote more about him than they did about Presidents Pierce or Buchanan.

All the characters in the film existed, though they aren’t all accurate portraits, and there’s no evidence -- say -- that Walker and his financier, Vanderbilt, ever met. Most of what happens in the film is part of some historical record; but it’s a drama, and the bricks of truth are mortared with fiction.

I first went to Nicaragua in 1984, with Peter McCarthy -- on one of those leftist tours where you meet nuns and trade unionists and representatives of cooperatives. It was the week of the presidential election, which the FSLN -- the Sandinistas -- won. We were impressed by the revolution, by the beauty of the countryside, by the changes and the optimism in the air. In Leon, on election day, two young Sandinistas egged us on to bring a big, Hollywood movie to Nicaragua, which would communicate something about Nicaragua to the Americans, and spend dollars there.

Fair enough. Nicaragua was a poor country, under continuous terrorist attack. The Sandinistas were their elected representatives, who’d led the overthrow of the dictator, Somoza, in 1979. Not that this meant much in Hollywood. To get serious money for a Sandinista feature, it would need an American protagonist. Step forward, William Walker.

For another excerpt, see Richard's

own post about acquiring the book.

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 2/17/2008

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Nicaragua,

Scott William Carter,

Cormac McCarthy,

China Mieville,

film,

Linkdump,

China Mieville,

Cormac McCarthy,

Nicaragua,

Scott William Carter,

Add a tag

I have finally made my way through the 3,000 emails that had accumulated in the mumpsimus at gmail account during my absence from checking it. Thank you to everyone for bearing with me on that. If you need a response of some sort to something, and I haven't yet replied, please send me another note, because I think I have responded to everything that seemed to need a response.

There are some sites and items I discovered from the mail, including:

- The First Book, a site created by Scott William Carter to provide interviews with and information about authors of first novels. Scott was my roommate at the very first science fiction convention I went to, and he's not only a tremendous nice guy, but has developed a great career with lots of short stories published in a wide variety of markets and now a novel that is forthcoming from Simon & Schuster in 2010.

- Noticing my comments on Cormac McCarthy's The Road, Henry Farrell let me know about a conversation with China Miéville about The Road that he had a year ago. I completely missed this when it was first posted (probably because I'd just gotten back from Kenya), and regret that, because it's very much worth reading.

- Starship Sofa is a science fiction podcast with a great selection of material -- right now there's a podcast (mp3) about the life and career of the much-too-neglected John Sladek, and past shows have included readings of stories by Pat Murphy, Bruce Sterling, David Brin, and others.

- This isn't from the mail, but I'll add it here anyway: A thoughtful review of the soon-to-be-released Criterion Collection DVD of Alex Cox's Walker

. This is an extraordinary movie, and I'm looking forward to seeing the DVD very much, because I've only ever watched it on an old videotape I got a few years ago, and the image quality on the tape is awful. I first got interested in Walker after I returned from a trip to Nicaragua and started reading up on Central American history -- and one of the stories that most captured my attention was that of William Walker, who took a ragged band of ruffians down to Nicaragua and declared himself president. Cox turned the story into a bizarre movie, and when I first watched it my reaction was basically, "Huh?" But a second viewing endeared the movie to me, and Ed Harris's performance as Walker is extraordinary -- he's one of the best actors out there, but seldom gets a chance to really show what he can do to the extent he got with Walker. The film is a political satire, an over-the-top historical epic, a chaotic mix of anomalies and goofiness, a sad and affecting tale of American capitalism and imperialism. Other films were made in '80s about Nicaragua -- Under Fire and Latino come to mind -- but Walker has more depth and nuance (even amidst its blustery weirdness) than its more straightforward and painfully earnest cousins, and it has withstood the passing of time all the better for it.

. This is an extraordinary movie, and I'm looking forward to seeing the DVD very much, because I've only ever watched it on an old videotape I got a few years ago, and the image quality on the tape is awful. I first got interested in Walker after I returned from a trip to Nicaragua and started reading up on Central American history -- and one of the stories that most captured my attention was that of William Walker, who took a ragged band of ruffians down to Nicaragua and declared himself president. Cox turned the story into a bizarre movie, and when I first watched it my reaction was basically, "Huh?" But a second viewing endeared the movie to me, and Ed Harris's performance as Walker is extraordinary -- he's one of the best actors out there, but seldom gets a chance to really show what he can do to the extent he got with Walker. The film is a political satire, an over-the-top historical epic, a chaotic mix of anomalies and goofiness, a sad and affecting tale of American capitalism and imperialism. Other films were made in '80s about Nicaragua -- Under Fire and Latino come to mind -- but Walker has more depth and nuance (even amidst its blustery weirdness) than its more straightforward and painfully earnest cousins, and it has withstood the passing of time all the better for it.

self-promo dealy.

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets.

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets. Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.

Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.

[…] Introducing “The Finding Corte Magore Project”. […]