|

| via Philip Taylor, Flickr |

In talking with Robin DeRosa about open educational resources (OER), a lot of my skepticism was focused on (and continues to be focused on) the question of who pays for it. If I'm not just skeptical but also cynical about a lot of the techno-utopian rhetoric that seems to fuel both the OER advocates and, even more so, people who associate themselves with the idea of Digital Humanities, it may be because I've been paying attention to what the internet has done to writers over the last couple decades. It's not all bad, by any means — this blog is one of example of that, I continue to try to write mainly for online venues so that my work can be relatively easily and broadly accessed, and I put most of my syllabi online. I can do that because I have other income and don't rely on this sort of writing to pay the bills. Thus, in my personal calculations, accessibility is more important than revenue.

But that freedom to choose accessibility over getting paid, or over doing work other than writing that would pay me, is a gigantic luxury. I can only make such a calculation because I have other revenue (the stipend from the PhD program I'm in and money saved from selling my father's business, which, though it's not enough to let me stop working, pays a bit over half of my basic expenses), and so the cost of my writing for free here on this blog, rather than doing remunerative work, is absorbed by that other revenue.

Further, aside from blog posts and some academic material, I usually won't write for free. Both because there are, in fact, people who will pay me, and also because I don't want to de-value the work of writing. Letting people have your work for free means they begin to expect that such work ought to be free. And while yes, in a post-capitalist utopia, I'd love for all work to be free ... we are, alas, not living in a post-capitalist utopia (as you might've noticed). Bills must still be paid. Printers and managers and bosses and technicians all get paid. And therefore writers should be paid.

In our Q&A, Robin said, "For materials to be 'open,' they need to be both free as in no-cost (gratis) and free as in free to repurpose and share (libre)."

It's that "no cost" that seems to me dangerous — the idea that there is no cost. Of course there's a cost. There's the cost of labor, first of all, with somebody working, either for free or not (and if for free then how are they paying their bills?). But then there are all the other things: the cost of bandwidth and of technological infrastructure, for instance.

Somebody is paying, even if it's not you.

OER is not no-cost, it's a movement of cost from one place to another. And that may be exactly what's necessary: to move costs from a place that is less fair or sustainable to one that is more fair and sustainable. That's in many ways a central idea of academic research: the institution pays the researcher a salary so that the researcher doesn't have to live off of the profits of research, thus keeping the research from being tainted by the scramble for money and the Faustian bargains such a scramble entails. (Of course, in reality, research — especially expensive technical research — is full of Faustian bargains. As public money gets more and more replaced by private money, those bargains will only get worse.) (And this, as OER advocates, among others, have pointed out, has also led to plenty of exploitation by some academic publishers, who enrich themselves while using the unfortunate reality of "publish or perish" as an excuse to not pay writers, to steal their copyright, etc.)

OER must highlight its costs, because hiding costs tends to further the idea that something not only is free, but should be free — and it's that idea that has destroyed wages for so many writers and artists over the last couple decades. To combat this, I think teachers should tell students the reality, for instance by saying something like: "Your tuition dollars fund 80% of this school's activities, including the salaries of the faculty who have worked countless hours to create these materials that we are not charging you for, because you have effectively paid for them through tuition." Or even: "I created this material myself and am releasing it to the world for no cost, but of course there was a cost to me in time and effort, and when I'm paid $2,500 minus taxes to teach this class, that basically means I'm giving this away, though I hope it doesn't mean it has no value."

Robin brought up Joss Winn's essay "Open Education: From the Freedom of Things to the Freedom of People", which is well worth reading for its critique of OER, but which stumbles when trying to offer a vision of another route — it ends up vague and, to my eyes, rather silly, because Winn has no practical way to prevent tools that are highly attractive to neoliberalism becoming tools for resistance to neoliberalism, and so concludes with little more than "and then a miracle occurs". (For the best commentary I've seen on the topic of resisting neoliberalism, see Steven Shaviro's No Speed Limit.)

Richard Hall asks huge, even overwhelming, but I think necessary questions about all this:

The issue is whether it is possible to use these forms of intellectual work as mass intellectuality, in order to reclaim the idea of the public, in the face of the crisis of value? Is it possible to reconsider pedagogically the relation between the concrete and the abstract as they are reproduced globally inside capitalism? Is it possible to liberate the democratic capability of academic labour, first as labour, and second as a transnational, collective activity inside open co-operatives, in order to reorient social production away from value and towards the possibility of governing and managing the production of everyday life in a participatory manner?My immediate, perhaps knee-jerk answer to any of the "Is it possible?" questions here is: Not in American higher ed, at least as I've known it, and not without a massive transformation of labor relations within higher ed. The US government and US schools are too deeply entrenched in neoliberalism, and without radically reforming academic labor, reforming the products of that labor is likely to be exploitative. Cooperative governance, associational networks, open co-operatives, etc. are all nice ideas, ones I in fact generally support and want to be part of, but such support comes with the awareness that if you're getting paid $70,000 a year and I'm getting paid $16,000 a year, our participation in those networks and co-operatives cannot be equal no matter how much you and I might agree that co-operatives and associational networks are better than the alternative. Further, if you were hired 20 years ago under vastly different conditions of hiring, your position is not my position. It's all well and good for you, Tenured Prof, to tell people they should publish in open access journals, but from where I sit, I don't trust that any hiring committee, never mind tenure and promotion, is going to value that in the way they value those highly paywalled journals. Hierarchies gonna hierarch.

OER advocates know this. They may know it better than anybody, in fact, since they're actively trying to bring hiring and tenure practices into the current century. One of the first pieces Robin edited when she was brought on board by Hybrid Pedagogy was Lee Skallerup Bessette's important essay "Social Media, Service, and the Perils of Scholarly Affect", which includes the fact (among many others) that one can, through open publishing and social media, etc., actually become not only a highly-cited secondary source but an actual primary source ... and have no way to turn that into "scholarship" recognized by gatekeepers.

But again, even while knowing that OER advocates are some of the people most aware of these problems, I can't help but come back to the question of how OER work can prevent the immediate effect of devaluing academic labor — how can it avoid being co-opted by the forces of neoliberalism?

I also can't help thinking about what we might call the Dissolve problem. The Dissolve was a wonderful film website sponsored by Pitchfork. It published great material and paid its writers. It is recently dead, and its archives could soon be wiped away if Pitchfork decides it's too expensive to maintain (as happened with SciFiction, the great online magazine sponsored by the Sci Fi Channel). Here's Matt Zoller Seitz on the end of The Dissolve:

Anybody who's tried to make a go at supporting themselves through writing or editing or other journalism-related work—criticism especially — without a side gig that's actually the "real" job, or partner or parent who pays most of the bills, can read between the lines. Staring at a blank page every day, or several times a day, and trying to fill it with words you're proud of, on deadline, with few or no mistakes, and hopefully some wit and insight and humor, is hard enough when it's the only thing you do. The days when it was the only thing writers did seem to recede a bit more by the week. It's even harder to make a go at criticism in today's digital media era, now that audiences expect creative work (music, movies and TV as well as critical writing) to be free, and advertisers still tend to equate page views with success. These factors and others guarantee that writer and editor pay will continue to hover a step or two above "exposure," and that even the most widely read outlets won't pay all that much. Most veteran freelancers will tell you that they earn half to a quarter of what they made in the 1990s, when newspapers and magazines were king. I make the same money now, not adjusted for inflation, with two journalism jobs and various freelancing gigs as I made in 1995 with one staff writing job at a daily newspaper.It's the trends that Matt highlights there that so concern me with OER, because I'm not sure how OER avoids perpetuating those trends. The ideals of no-cost are lovely. But the process of getting there can't be waved away with magic thinking. Free free free poof utopia!

More likely, poof nobody makes money except the administrative class.

Could it be that OER advocates are like John Lennon imagining there's no money ... when he's a gazillionaire? To which the necessary response is: "No money? Easy for you to imagine, buster!"

Let's do a thought experiment, though, and imagine that OER advocates somehow square the circle of doing non-exploitative work in neoliberal institutions. (And already I'm speaking in terms of miracles occurring!) What happens to students who then go out into the world and continue to expect every creative and intellectual product to be free? Heck, they already do. And such assumptions contribute to the de-valuing of writers' and artists' labor as well as the de-valuing of academic labor.

That's why I think our job as educators should be to push against such assumptions rather than to encourage them, because encouraging the idea that creative and intellectual work should be free and has no costs just leads to the impoverishment of creative and intellectual workers.

Pushing against such assumptions wouldn't mean the need to give up or disparage OER, but rather to make the processes of its creation, dissemination, and funding as transparent as possible. Answer even the basic questions such as "Who pays for the bandwidth?"

Without such transparency, OER, I fear, will perpetuate not only the trends that have led to the adjunctification of higher ed, and the trends that have brought on a catastrophic defunding of public education, but also the trends that destroyed The Dissolve. Without helping people see that, in our economy, "free" really means a displacement of cost (somebody else paying ... or somebody not getting paid), OER will perpetuate destructive illusions.

0 Comments on Gratis & Libre, or, Who Pays for Your Bandwidth? as of 7/10/2015 4:12:00 PM

Add a Comment

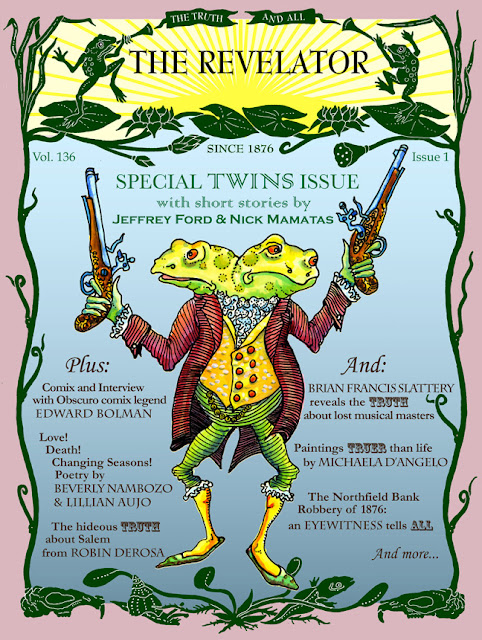

This looks amazing. Will there be submission guidelines?

No submission guidelines because we're not accepting unsolicited submissions right now, alas.

That looks awesome. Congratulations!