new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Sixties British Pop, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Sixties British Pop in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 11/19/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Music,

emi,

the beatles,

please please me,

*Featured,

george martin,

Sixties British Pop,

Gordon R. Thompson,

Andy White,

session musicians,

Add a tag

Every major news source last week carried news of Andy White’s death at 85. The Guardian’s “Early Beatles Drummer Andy White Dies at 85” represents a typical article title intended to attract readers albeit with misinformation that suggests that a particular two-minute-and-twenty-second episode from his life should be why we remember him.

The post Not a Beatle: Andy White appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 6/4/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Music,

Mick Jagger,

please please me,

rolling stones,

Keith Richards,

*Featured,

Sixties British Pop,

Gordon R. Thompson,

Andrew Oldham,

Satisfaction (song),

Sixties British Pop Inside Out,

Add a tag

In the spring of 1965, The Rolling Stones could be forgiven their frustration. Even though they had scored three number-one UK hits in the past year, the American market remained a challenge. Beatles recordings had already thrice dominated the US charts since New Year’s Day and Brits Petula Clark, Herman’s Hermits, Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders, and Freddie and the Dreamers had all topped Billboard between January and May.

The post The Stones’ “Satisfaction,” June 1965 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 8/7/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

the beatles,

please please me,

The Rolling Stones,

Shel Talmy,

Ray Davies,

the kinks,

Joe Meek,

Sixties British Pop,

Gordon R. Thompson,

Dave Clark Five,

Dave Berry,

Davies Brothers,

Denmark Street,

Geoff Stephens,

Honeycombs,

Ken Howard,

Marianne Faithful,

Mitch Murray,

The Crying Game,

Books,

Music,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Alan Blaikley,

Add a tag

By Gordon R. Thompson

In the opening months of 1964, The Beatles turned the American popular music world on its head, racking up hits and opening the door for other British musicians. Lennon and McCartney demonstrated that—in the footsteps of Americans like Buddy Holly and Chuck Berry—British performers could be successful songwriters too. In the summer, “A Hard Day’s Night” would prove that their success had not been a winter fluke or a momentary bit of post assassination frenzy.

It wasn’t that the Brits had been absent from the very profitable American market: Joe Meek had had success with the Tornados’ “Telstar” at the end of 1962. But before The Beatles, few in America cared much at all about what the British recording industry released. Indeed, British irrelevancy lay behind Capitol’s decision not to release recordings by The Beatles until news coverage got ahead of them.

In the wake of the Beatles, some of the evolving diversity of British songwriting emerged and the first stage came from composers associated with the heart of London’s music publishing world: Denmark Street. Publishers and musical instrument stores still call that short stretch of pavement home, but in the early to mid-sixties, everyone from the Beatles to the Kinks had been there. You could record at Regent Sound Studios (as did The Rolling Stones and The Who), you could grab a coffee with session musicians at Julie’s Café, or buy an ad at either Melody Maker or The New Musical Express. Indeed, The Beatles had gotten a huge break through publisher Dick James whose offices were at the corner of Denmark Street and Charing Cross Road.

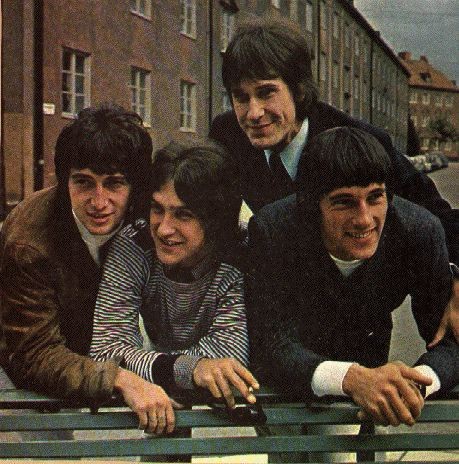

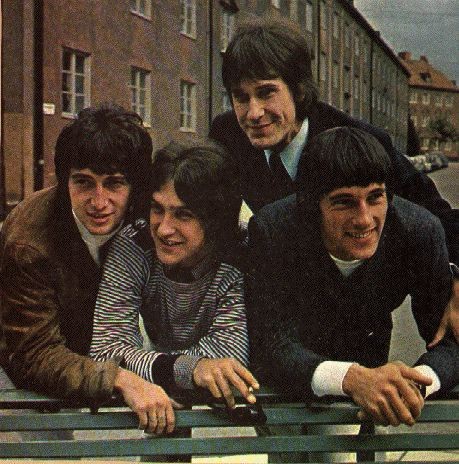

A promotional photo of British rock group The Kinks, taken in Stockholm, Sweden, ca. 2 September 1965. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1963, Lennon and McCartney’s major competitor was Mitch Murray who had had a string of hits with Gerry and the Pacemakers (“How Do You Do It?”) and Freddie and the Dreamers (“I’m Telling You Now”). Murray’s forte was the simple, catchy lyric and tune, purchased and consumed in an instant, paid for by happy teens who eagerly waited for the next release. His songs had proved so successful in 1963 that John Lennon jokingly (perhaps) suggested that another challenge to the Lennon-McCartney catalogue could result in bruises for their competitor. Notably in this period, both the Liverpudlians and this Londoner published through Dick James Music.

However a particularly interesting composition emerged from the pen of another Denmark Street songwriter, this time associated with Southern Music. The twenty-nine-year-old Geoff Stephens was never much of a musician, but he had an ear for lyrics and tunes and “The Crying Game” had begun as a title and a premise. The title “seemed the perfect seed from which to grow a very good pop song,” he recalled. “We all know what it’s like to cry and have deep feelings.” Still, the song’s convoluted melody and irregular prosody made it an unlikely hit for 1964, but succeed it did.

Click here to view the embedded video.

A winning interpretation would come through Dave Berry whose breathy and exposed voice served as the perfect instrument for the melody, even if he initially thought the music inappropriate for him. (He saw himself as a rhythm-and-blues artist.) Decca producer Mike Smith (who had auditioned the Beatles back in 1962) brought in Reg Guest to serve as music director who, in turn, hired guitarist Big Jim Sullivan to complement Berry’s emotive interpretation. Employing a foot pedal meant for a steel guitar that controlled both tone and volume, Sullivan put the musical equivalent of crying into the recording. The result deeply impressed Beatle George Harrison who sought to find out how to recreate the sound (something he would accomplish the next year on songs like “I Need You” and “Yes It Is”).

Not all non-performer songwriters in this era had deep ties to Denmark Street. Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley had met at University College School as teens, sported proper academic degrees, had worked at the BBC, and were active participants in the intellectual world of late fifties and early sixties London. In 1964 they collaborated on the song “Have I the Right” and in a tavern found the Sheritons whom they believed were perfect to deliver their plea for love. The musical and lyrical materials are simple, but catchy, and demanded a distinctive sound and interpretation.

No one could better create a distinctive sound in London at the time than the enigmatic Joe Meek in his home studio on Holloway Road in North London. In order to create a sound around the band and the song, Meek turned to the four-on-the-floor musical grooves that had been popular that year (notably heard on recordings by another North London group, the Dave Clark Five). Meek recorded clipped microphones to the stairs outside his studio and had the band stomp in time with the music, perhaps in imitation of the Dave Clark Five’s “Bits and Pieces.” Next, he repeatedly overdubbed a guitar part and played with the tape speed to give it a wavering bell-like quality.

Howard and Blaikley would lease the recording to Louis Benjamin at Pye Records, who thought that the Sheritons needed a new name. Seeing the band’s female hairdresser-drummer Honey Lantree as its visual distinction and marketing hook, he renamed the band, The Honeycombs. The song topped British charts late in the summer and successfully climbed American charts that fall. The songwriters would become the band’s managers and continue to write music for them, although they never quite duplicated their success.

Click here to view the embedded video.

But where were British songwriters who also performed their own material? Jagger and Richards of The Rolling Stones had written “As Tears Go By,” but had decided to give it to Marianne Faithful. (They didn’t think it appropriate for themselves to release, at least as a single.) The band had also recorded a demo of another Jagger-Richards tune, “Tell Me,” at Regent Sound Studios in Denmark Street, only to discover that their manager Andrew Oldham had released it in America. Despite its modest success, Richards has since cited this recording as evidence of how little control they had over their career at this stage. They wouldn’t record their first real self-penned success early the next year with “The Last Time.”

More significantly during the summer of ‘64, one of the most important British artists of the era woke up every garage band on both continents, simultaneously frightening parents and the custodians of culture.

In July 1964 at IBC Studios in London, Shel Talmy prepared to give an unlikely group of musicians their last chance to have a hit. Talmy was a Los Angeles transplant, an outsider to the London recording scene who preferred to work as an independent artist-and-repertoire manager. Through hard work, good luck, and a bit of bluff, he had managed almost immediate success, much to the jealousy of the locals.

The group on whom he was gambling had the Davies Brothers as its leaders who had beaten the odds to get a recording contract, but who had struck out with their first two releases. The Kinks’ version of Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally” had the misfortune of comparison with The Beatles, who were now using the tune to close their shows and who would soon release their own version of it. Their next attempt was a composition by Ray Davies. “You Still Want Me” carries all the hallmarks of early sixties British pop and, consequently, had very little that would distinguish The Kinks from everyone else.

“You Really Got Me” would be the song that lifted them to success. They arrived to record it at IBC Studios in July 1964 after already taping a slower and more bluesy version. Davies and Talmy (although they might disagree about the process later) agreed that a faster version could be more successful and booked time at the studio late at night. To insure success, Talmy had engaged session drummer Bobby Graham, who was already known around professional circles as at least one of the drummers on the Dave Clark Five records. He also brought in the veteran bandleader Art Greenslade to play piano.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Graham and Greenslade had been at a previous recording session earlier that night where a contractor had asked them to do a second session. After a pint or two and a bite to eat, they showed up at IBC for a date with the Kinks. Their first reaction, according to Greenslade, was a one of slightly restrained horror at the sight of the band; but, after a short rehearsal, they settled into a good working relationship. The band’s drummer, Mick Avory, settled into playing the tambourine.

Knowing full well, that you get six sides to get a hit, Ray Davies remembered years later the tension that night. “When that record starts it’s like… doing the four-minute mile; there’s a lot of emotion.” He remembers shouting at Dave, “willing him to do it, saying it was the last chance we had.” Brother Dave apparently responded with an expletive and launched into what must be one of the original punk guitar solos played through a ripped speaker. Talmy, for his part, tried to capture the sound and to shape it in a distinctive way, employing the young Glyn Johns and Bob Auger as his engineers.

The recording of “You Really Got Me” would establish The Kinks as one of Britain’s most important bands and Ray Davies as a songwriter to be watched.

Gordon R. Thompson is Professor of Music and Chair of the Department of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Gordon Thompson will be speaking at a number of Capital District venues in February. His lecture, “She Loves You: The Beatles and New York, February 1964,” will contextualize that band’s historic relationship with the Empire State. Check out Gordon Thompson’s posts on The Beatles and other music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The British are coming: the Summer of 1964 (part two) appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 8/6/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Manfred Mann,

please please me,

rolling stones,

*Featured,

The Animals,

Arts & Leisure,

Sixties British Pop,

Gordon R. Thompson,

Dave Clark Five,

Books,

Music,

Add a tag

By Gordon R. Thompson

Fifty years ago, a wave of British performers began showing up on The Ed Sullivan Show following the dramatic and game-changing appearances by The Beatles. That spring, a number of “beat” groups made the transatlantic leap and scored hits on American charts prompting many pop pundits to declare (not for the last time) that the Beatles’ fifteen-minutes of fame had elapsed. The first pretenders to the throne were London’s The Dave Clark Five with “Glad All Over” (sung and written by organist Mike Smith with Dave Clark), which anticipated the many other British pop records that would find a place on American charts in the mid sixties. Soon, Liverpudlian performers The Searchers (“Needles and Pins”), Gerry and the Pacemakers (“Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying”), and Billy J. Kramer (“Bad to Me”) followed fellow Merseysiders The Beatles and debuted on the Sullivan’s Sunday-night show, even as other American networks scrambled to get their piece of the British pop pie.

Publicity photo of The Dave Clark Five from their cameo performing appearance in the US film Get Yourself a College Girl. 27 November 1964. (c) MGM. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Over the course of that year, the success of acts like these changed both American impressions of British music and, importantly, British musicians’ attitudes about themselves. After an era of economic hardship and the occasional geopolitical embarrassment (e.g., the Suez Crisis of 1956), Britain came out of its postwar cultural funk to the soundtrack of pop music. At least two interrelated trends in this music emerged. First, British artists followed the long-established practice of white performers covering music created by African Americans and, second, they began to explore their own versions of what those traditions might sound like. Often, their approach was to take material previously performed acoustically and reinterpret it with electric guitars and keyboards accompanied by drums. They also applied production forces that had not been available to the original performers. Ultimately, British producers, songwriters, and musicians began to find the confidence—sometimes tinged with arrogance—that they could compete with Americans.

“House of the Rising Sun.” This traditional ballad (collector Alan Lomax had recorded an Appalachian version in the thirties) about a life gone wrong in New Orleans had been included on Bob Dylan’s eponymous first album. The Animals from Newcastle had already extracted and interpreted a song that appears on that album for British charts (“Baby Let Me Take You Home”), applying blues-rock aesthetics to a folk ballad. In a way, The Animals’ version of “House of the Rising Sun” was an early example of folk rock.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Guitarist Hilton Valentine and keyboardist Alan Price found ways to update and electrify the instrumental accompaniment of “House of the Rising Sun,” and Eric Burdon gave it a convincing and ultimately defining interpretation. The session unfolded at the unglamorous hour of eight AM after the band had traveled overnight from a gig in Liverpool, arriving at Kingsway Studios (opposite the Holborn Underground station) tired, but excited to be recording again. The band ran through the arrangement they had been playing in clubs and did two takes; but the second proved unnecessary. Mickie Most, the artist-and-repertoire manager on the session, knew he had a hit. Most later told Spencer Leigh, “Everything was in the right place, the planets were in the right place, the stars were in the right place and the wind was blowing in the right direction. It only took 15 minutes to make.”

Most’s role in the success of mid-sixties British rock and pop cannot be overstated. He would produce recordings by Herman’s Hermits, the Nashville Teens, Donovan, the Yardbirds, and many others. In the case of “House of the Rising Sun,” Most made the unconventional call to press all 4 minutes and 28 seconds of the recording. The combination of microgroove technology and vinyl allowed for longer playing times and a cleaner sound from a 45 rpm disc, even if most singles still followed the industry norm of 2:30 established by 78 rpm shellac discs. Most concluded that, if the recording and the performance were good, the length would not matter. He was proved right, even if MGM (the American distributor) would break the recording up into two parts for radio play. Released on June 19th, the record would hit number 1 on British charts in July 1964 and soon proved successful on American charts as well such that the Animals would debut on The Ed Sullivan Show in October with a hit.

“Doo Wah Diddy Diddy.” Named after South African keyboardist Manfred Lubowitz’s stage persona, the London band Manfred Mann got their break when asked to write theme music for the popular ITV television show, Ready, Steady, Go! EMI artist-and-repertoire manager John Burgess had signed them and “5, 4, 3, 2, 1” — their second release — had become a hit, albeit one that derived its success through its association with a television show. Their self-penned follow-up—“Hubble Bubble (Toil and Trouble)”—rose to a respectable #11 on UK charts, but they hoped for a piece of the transatlantic prize that The Beatles, The Dave Clark Five, and others were enjoying. As with many British performers at the time, the band and their producer decided to cover a tune that had already been released by an American singing group.

Written by Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich in New York, The Exciters’ version of “Do Wah Diddy” featured a very basic instrumental backing and had been a regional success; but it had been unable to capture a national market. Indeed, recordings by African Americans often found release only on small independent labels that lacked national distribution and promotion structures. Burgess would have guessed that his band could give it a different spin and, with the current hunger for British acts in the US and parent company EMI’s growing clout, a good promotion and distribution arrangement would ensure success.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Paul Jones gives a constrained performance, his singing style featuring a much more constricted and nasal quality when compared to the original’s open-throated joyfulness. Burgess with Norman Smith (who also served as the balance engineer on Beatles recordings in this era) capture a slightly more elaborate instrumental performance that included timpani and Mann’s electronic keyboard prominently in the mix. More importantly, Smith’s soundscape for the recording adds a depth that was lacking in the original production by the Exciters. “Doo Wah Diddy Diddy” would not be the band’s last American hit, but it would be their biggest.

“It’s All Over Now.” The Rolling Stones had had hits in the UK with a covers of Chuck Berry’s “Come On,” Lennon and McCartney’s “I Wanna Be Your Man,” and Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away”; but success had largely evaded them in the US in the first half of 1964. The summer had not bode well for the Rolling Stones, with The Daily Mirror at the end of May describing them as the “ugliest group in Britain.” But manager Andrew Oldham, if nothing else, had ambitious plans for the band.

In anticipation of their short inaugural American tour, he released one of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards’ earliest attempts at songwriting (the poppish “Tell Me,” which the songwriters had intended only as a demo) in the US to very modest regional success, but they had yet to get to the number-one spot in either the UK or the US. Once the two-week American tour began in June 1964, they played to half-empty houses and an indifferent press. If the Stones were on the road to success, it was beginning to look unpleasant.

When the tour stopped in Chicago, Oldham arranged for them to record at the studios for Chess Records. American legends who loomed large in the band’s imagination had recorded here: Chuck Berry, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, and others had all spent time at 2120 South Michigan Avenue. With Ron Malo selecting and positioning microphones before setting levels, The Stones felt they were tapping into history, while manager Andrew Oldham understood a good marketing opportunity when he saw one.

One of the tunes they had heard in New York seemed like just the thing to record during this session. Bobby and Shirley Womack had written “It’s All Over Now” for Bobby’s band, the Valentinos, but again the disc had failed to achieve much success. Their version had something of Chuck Berry’s “Memphis, Tennessee” to its grove and feel, and a prominent bass line that drove the recording along provided a sense of humor and irony.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The Rolling Stones sped their version up and added an arpeggiated guitar part, while Mick Jagger delivered the lyrics as an angry victim who gains vindication, a role he would develop extensively in the coming years. When released in Britain on the June 26th, it would prove to be the Stones’ first chart topper the week after “House of the Rising Sun” had occupied that spot in July.

Click here to view the embedded video.

When asked the previous year about why British teens liked The Rolling Stones’ blues and rhythm-and-blues covers, Jagger acknowledged that their audiences liked white faces better. Indeed, British artists (including The Beatles) relied heavily on music originally created in the US by either African Americans or by rural whites.

As 1964 unfolded, songwriters, musicians, music directors, recording engineers, and artist-and-repertoire managers would gain self-confidence and begin producing something more identifiably British.

Gordon R. Thompson is Professor of Music and Chair of the Department of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Gordon Thompson will be speaking at a number of Capital District venues in February. His lecture, “She Loves You: The Beatles and New York, February 1964,” will contextualize that band’s historic relationship with the Empire State. Check out Gordon Thompson’s posts on The Beatles and other music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The British are coming: the Summer of 1964 (part one) appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KimberlyH,

on 2/22/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

Beatles,

paul mccartney,

1960s,

John Lennon,

gordon thompson,

please please me,

lennon,

mccartney,

Inside Out,

songwriters,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

george martin,

Parlophone,

Sixties British Pop,

Ardmore and Beechwood,

Brit Pop,

Dick James,

Helen Shapiro,

Northern Songs,

Sid Colman,

songwriting recording artists,

Southern Music,

nems,

Add a tag

By Gordon R. Thompson

Songwriting had gained the Beatles entry into EMI’s studios and songwriting would distinguish them from most other British performers in 1963. Sid Colman at publishers Ardmore and Beechwood had been the first to sense a latent talent, bringing them to the attention of George Martin at Parlophone. Martin in turn had recommended Dick James as a more ambitious exploiter of their potential catalogue and, to close the deal, James had secured a national audience for the Beatles. Nevertheless, as the band grew in popularity, James knew that McCartney and Lennon would attract the attention of other music publishers.

Most fans, unless they bought sheet music, were at best only vaguely aware that music publishers had any role at all in popular music, let alone that they controlled an economically critical part of the industry. Even Lennon and McCartney at first underestimated the importance of music publishing until probably the first royalty checks began arriving at manager Brian Epstein’s NEMS Enterprises offices. Every time someone purchased a recording of one of their songs—no matter by whom—both the songwriters and the publisher profited. And every play on the radio and every television appearance did the same.

The home of Britain’s music publishing industry resided in London’s Denmark Street, a one-block stretch of offices, studios, and stores near Soho, serviced by a small pub, a café, and a steady stream of aspiring songwriters. Dick James’s office sat at the corner of Denmark Street and Charing Cross Road, not far from the premises of Southern Music, Regent Sound Studios, and other music-centered establishments. Brian Epstein had walked into these offices in November with a copy of “Please Please Me” and the hope that James could break the Beatles into the national media. James delivered immediately, booking an appearance for the band on the 19 January 1963 edition of ABC’s television show, Thank Your Lucky Stars.

The traditional role of the music publishers was to plug songs, bringing them to the attention of artist-and-repertoire and/or personal managers in an effort to have them match compositions with performers; but rock and roll was changing that model. When EMI’s Columbia Records released Cliff Richard and the Drifters’ recording of Ian Samwell’s “Move It” in August of 1958, London saw the start of musicians performing their own music. The tradition only deepened with Johnny Kidd and the Pirates’ “Shakin’ All Over” in June 1960. American artists such as Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, and Carl Perkins routinely wrote and recorded their own material, unlike singer Bobby Rydell or many other pop stars who performed material written by professional songwriters. In Britain, songwriting recording artists often proved fleeting phenomena.

With “Love Me Do” and “Please Please Me,” as well as a number of other originals that would appear on their first album Please Please Me, John Lennon and Paul McCartney demonstrated their ability to write and perform their own material with spectacular results. Nevertheless, they knew the model and their first efforts to write a song for another performer met with mixed results. Touring with Helen Shapiro, the two songwriters futilely attempted to convince her and her management to record their song “Misery.” Another performer on the show, Kenny Lynch happily picked up the tune and very soon other artists would be looking for songs by McCartney and Lennon. Dick James, perhaps worried that with greater success the two ambitious Liverpudlians (and their manager) might bolt for yet another publisher, sought a strategy that would keep them as clients.

Click here to view the embedded video.

McCartney and Lennon were not the only songwriting performers in London. Southern Music had contracted eager songwriters and willing performers John Carter and Ken Lewis (later the core of the singing group the Ivy League) to write for the publisher. Their mentor at Southern, Terry Kennedy had even dubbed their band the “Southerners” (with a young Jimmy Page on guitar). However, they tended to write tunes for other singers and to perform songs written by other songwriters, all under the umbrella of their publisher.

Dick James’s big idea was to have John Lennon and Paul McCartney become part owners of their own publishing venture: Northern Songs. The arrangement that Epstein, McCartney, and Lennon made with James must have seemed good at the time, especially given that most young composers had no income from their work other than their author royalties. Northern Songs rewarded the two Liverpudlians with a larger piece of the pie, dividing the ownership of company between (i) Dick James Music, (ii) NEMs, (iii) Lennon, and (iv) McCartney. Dick James Music held a 51% voting share, leaving Lennon and McCartney each 20%, and NEMS Enterprises picking up the remaining 9%; however, James also took a 10% administrative fee off the top, so that in practice, the songwriters and their manager shared about 44% of the income.

Lennon and McCartney already had an agreement with Epstein to write songs, but a company dedicated to their music brought the game to an entirely new level. This would not be the last time that they would be the first to explore new territory in the business, from which other rock and pop artists and their managements would learn.

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Check out Gordon Thompson’s posts on The Beatles and other music here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Beatles and Northern Songs, 22 February 1963 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/25/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

george harrison,

emi,

the beatles,

gordon thompson,

please please me,

lennon,

mccartney,

brian epstein,

*Featured,

Love Me Do,

Arts & Leisure,

luxembourg,

barrow,

george martin,

New Musical Express,

Parlophone,

Radio Luxembourg,

Record Mirror,

Sixties British Pop,

Tony Barrow,

barrow,

Music,

BBC,

1960s,

Add a tag

By Gordon R. Thompson

As a regional businessman and a fledgling band manager, Brian Epstein presumed that the Beatles’ record company (EMI’s Parlophone) and Lennon and McCartney’s publisher (Ardmore and Beechwood) would support the record. This presumption would prove false, however, and Epstein would need to draw on all of the resources he could spare if he were to make the disc a success. He began with what he knew from the retail end of the industry and commenced rallying Liverpudlians to write letters to both Radio Luxembourg and the BBC asking them to play “Love Me Do.”

Just as the stations XERF (in Ciudad Acuña, Mexico) and CKLW (in Windsor, Ontario, Canada) were able to broadcast deep into the United States with transmitters many times more powerful than FCC-regulated American stations, a station in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg carpeted most of Western Europe. Perhaps surprisingly, Radio Luxembourg (broadcast in the Medium Wave band) was British-owned and its English-language service became a primary outlet for UK businesses whose advertising the BBC declined. (The BBC refused to broadcast anything that suggested product promotion.) Radio Luxembourg suffered its sometimes-scratchy signal; but British listeners tuned in every night to embrace the pop music that Aunty Beeb would not play.

Expo 1958 Radio Luxembourg by Wouter Hagens. Creative Commons License.

British corporations like EMI and London music publishers like Essex Music directly controlled much of the station’s airtime by buying broadcast blocks during which they played pre-recorded programs. Indeed, on Monday 8 October 1962, the Beatles taped an interview at EMI’s headquarters in London, which Radio Luxembourg broadcast along with their recording of “Love Me Do” on Friday 12 October. (George Harrison later recalled the thrill of first hearing himself on that radio broadcast.) The Liverpool letters solicited by Epstein that arrived in Luxembourg eventually arrived at EMI in London where the manager hoped they would catch corporate attention and result in better domestic support for the Beatles and their releases.

Tony Barrow, whom Epstein had originally contacted at Decca Records in his quest to get the Beatles a recording contract, began work for NEMS (North End Music Stores) as the Beatles’ publicist. (He could hardly have imagined how his job description would evolve from soliciting the press’s attention to holding them at arm’s length.) As a reviewer and a liner-note writer, Barrow had often worked from press materials prepared by agents and managers. These releases could vary significantly in kind and quality, but among them, Barrow thought that the press kits from Leslie Perrin’s office (which had represented London’s infamous Raymond’s Revue Bar, among others) were particularly effective. Notably, a color-coded press kit walked readers through a client’s story, which made a reviewer’s tasks easier. Barrow appropriated this format in his preparations for promoting the Beatles.

The role of the press agent involved finding the right people to contact and, for that, Barrow needed names, addresses, and phone numbers. Coincidentally, he knew someone who had recently left Decca’s press office. The Beatles’ new agent presumed that the individual would have taken a copy of the company’s mailing list and, after a casual meal, they reached a mutually beneficial agreement. Brian Epstein’s new part-time press manager walked away with a cache of contacts.

Barrow began by introducing the Beatles to London’s music press, escorting the Liverpudlians from the Denmark Street offices of New Musical Express to Fleet Street’s Melody Maker. They were willing to go almost anywhere to meet anyone with access to print or broadcast media. For example, on 9 October 1962 (the day after taping the Radio Luxembourg program), they visited the offices of Record Mirror so that writers there could see how different they were from other entertainers and to hopefully experience some of the charm that had swayed George Martin.

The mixed results both encouraged the band and its manager, and disappointed them. Alan Smith, writing in the New Musical Express (26 October 1962), briefly introduced the band, highlighting how Lennon and McCartney had written their “hit.” However, if you were the Beatles searching the papers for even the briefest mention (which they did weekly), you found little.

Brian Epstein in a 1967 interview would justifiably take credit for some of the band’s early success, citing his diligence and perseverance. The slow climb of “Love Me Do” up the charts would be his vindication. By December 1962, despite setbacks, the single increased sales and nudged into the top twenty on the most respected (if selectively read) chart. They were poised for something and they were sure ‘twas for success.

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Check out Gordon Thompson’s posts on The Beatles and other music here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Selling the Beatles, 1962 appeared first on OUPblog.