new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: currency, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 9 of 9

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: currency in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Monica Gupta,

on 8/6/2016

Blog:

Monica Gupta

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Currency,

Haryana,

RBI,

10 Rupees Coin,

Indian Currency,

latest news in india,

Reserve Bank of India,

Reserve Bank of India (RBI),

अफवाह,

दस रुपये का सिक्का,

रोक और अफवाह,

Articles,

10,

Add a tag

दस रुपये का सिक्का, रोक और अफवाह हमारे देश में, बेशक, मुद्दा गाय का उछलता हो पर यहां भेडचाल बहुत है… !!! पिछ्ले तीन चार दिन से मार्किट से सामान लेने पर 10 रुपये के सिक्के बहुत वापिस मिले. मेरे पास करीब 200 रुपए के सिक्के हो गए. बार बार सिक्के देख कर हैरानी तो […]

The post दस रुपये का सिक्का, रोक और अफवाह appeared first on Monica Gupta.

By: DanP,

on 11/12/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Economics,

business,

Journals,

money,

Finance,

economy,

stock market,

profit,

*Featured,

currency,

Business & Economics,

oxford journals,

stock exchange,

chen xue,

financial studies,

kewei hou,

lu zhang,

stock returns,

the review of financial studies,

Add a tag

For investors and asset managers, expected stock returns are the rates of return over a period of time in the future that they require to earn in exchange for holding the stocks today. Expected returns are a central input in their decision process of allocating wealth across stocks, and are essential in determining their welfare. For corporate managers, expected returns on the stocks of their companies, or the costs of equity, are the rates of returns over a period of time in the future that their shareholders require to earn in exchange for injecting equity to their companies today. The costs of equity play a key role in the decision process of corporate managers when deciding which investment projects to take and how to finance the investment. Despite the paramount importance, no consensus exists on how to best estimate expected stock returns. In fact, one of the most important challenges in academic finance is to explain anomalies, empirical patterns of expected stock returns that seem to evade traditional theories.

A manager should optimally keep investing until the investment costs today equal the value of future investment benefits discounted to today’s dollar terms, using her firm’s expected stock return as the discount rate. This economic logic implies that all else equal, stocks of firms with high investment should have lower discount rates than stocks with low investment. Intuitively, low discount rates lead to high discounted values of new projects and high investment. In addition, stocks with high profitability (investment benefits) relative to low investment should have higher discount rates than stocks with low profitability. Intuitively, the high discount rates are necessary to offset the high profitability to induce low discounted values for new projects and low investment.

To implement this idea, we use a standard technique in academic finance that “explains” a stock’s return with the contemporaneous returns on a number of factors. In a highly influential study, Fama and French (1993) specify three factors: the return spread between the overall stock market and the one-month Treasury bill, the return spread between small market cap and big market cap stocks, and the return spread between stocks with high accounting relative to market value of equity and stocks with low accounting relative to market value of equity. Carhart (1997) forms a four-factor model by augmenting the Fama-French model with the return spread between stocks with high prior six to twelve month returns and stocks with low prior six to twelve month returns.

We propose a new four-factor model, dubbed the q-factor model, which includes the market factor, a size factor, an investment factor, and a profitability factor. The market and size (market cap) factors are basically the same as before. The investment factor is the return spread between stocks with low investment and stocks with high investment. The profitability factor is the return spread between stocks with high profitability and stocks with low profitability. The q-factor model captures most of the anomalies that prove challenging for the Fama-French and Carhart models in the data.

Specifically, during the period from January 1972 to December 2012, the investment factor earns an average return of 0.45% per month, and the profitability factor earns 0.58%. The Fama-French and Carhart models cannot capture our factor returns, but the q-factor model can capture the returns on the Fama-French and Carhart factors. More important, the q-factor model outperforms the Fama-French and Carhart models in “explaining” a comprehensive set of 35 significant anomalies in the US stock returns. The average magnitude of the unexplained returns is on average 0.20% per month in the q-factor model, which is lower than 0.55% in the Fama-French model and 0.33% in the Carhart model. The number of unexplained anomalies is 5 in the q-factor model, which is lower than 27 in the Fama-French model and 19 in the Carhart model. The q-factor model’s performance, combined with its economic intuition, suggests that it can serve as a new benchmark for estimating expected stock returns.

The post A new benchmark model for estimating expected stock returns appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 8/6/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Economics,

Current Affairs,

money,

America,

Finance,

wealth,

economy,

reserve’s,

Wall Street,

transparency,

*Featured,

currency,

monetary,

Business & Economics,

Richard Grossman,

Federal Reserve,

economic growth,

Economic Policy with Richard S. Grossman,

grossman,

economic policy,

federal bank,

federal funds,

federal policy,

Wrong nine economic policy disasters,

fomc,

fed’s,

montagu,

Add a tag

By Richard S. Grossman

As an early-stage graduate student in the 1980s, I took a summer off from academia to work at an investment bank. One of my most eye-opening experiences was discovering just how much effort Wall Street devoted to “Fed watching”, that is, trying to figure out the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy plans.

If you spend any time following the financial news today, you will not find that surprising. Economic growth, inflation, stock market returns, and exchange rates, among many other things, depend crucially on the course of monetary policy. Consequently, speculation about monetary policy frequently dominates the financial headlines.

Back in the 1980s, the life of a Fed watcher was more challenging: not only were the Fed’s future actions unknown, its current actions were also something of a mystery.

You read that right. Thirty years ago, not only did the Fed not tell you where monetary policy was going but, aside from vague statements, it did not say much about where it was either.

Given that many of the world’s central banks were established as private, profit-making institutions with little public responsibility, and even less public accountability, it is unremarkable that central bankers became accustomed to conducting their business behind closed doors. Montagu Norman, the governor of the Bank of England between 1920 and 1944 was famous for the measures he would take to avoid of the press. He adopted cloak and dagger methods, going so far as to travel under an assumed name, to avoid drawing unwanted attention to himself.

The Federal Reserve may well have learned a thing or two from Norman during its early years. The Fed’s monetary policymaking body, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), was created under the Banking Act of 1935. For the first three decades of its existence, it published brief summaries of its policy actions only in the Fed’s annual report. Thus, policy decisions might not become public for as long as a year after they were made.

Limited movements toward greater transparency began in the 1960s. By the mid-1960s, policy actions were published 90 days after the meetings in which they were taken; by the mid-1970s, the lag was reduced to approximately 45 days.

Since the mid-1990s, the increase in transparency at the Fed has accelerated. The lag time for the release of policy actions has been reduced to about three weeks. In addition, minutes of the discussions leading to policy actions are also released, giving Fed watchers additional insight into the reasoning behind the policy.

More recently, FOMC publicly announces its target for the Federal Funds rate, a key monetary policy tool, and explains its reasoning for the particular policy course chosen. Since 2007, the FOMC minutes include the numerical forecasts generated by the Federal Reserve’s staff economists. And, in a move that no doubt would have appalled Montagu Norman, since 2011 the Federal Reserve chair has held regular press conferences to explain its most recent policy actions.

The Fed is not alone in its move to become more transparent. The European Central Bank, in particular, has made transparency a stated goal of its monetary policy operations. The Bank of Japan and Bank of England have made similar noises, although exactly how far individual central banks can, or should, go in the direction of transparency is still very much debated.

Despite disagreements over how much transparency is desirable, it is clear that the steps taken by the Fed have been positive ones. Rather than making the public and financial professionals waste time trying to figure out what the central bank plans to do—which, back in the 1980s took a lot of time and effort and often led to incorrect guesses—the Fed just tells us. This make monetary policy more certain and, therefore, more effective.

Greater transparency also reduces uncertainty and the risk of violent market fluctuations based on incorrect expectations of what the Fed will do. Transparency makes Fed policy more credible and, at the same time, pressures the Fed to adhere to its stated policy. And when circumstances force the Fed to deviate from the stated policy or undertake extraordinary measures, as it has done in the wake of the financial crisis, it allows it to do so with a minimum of disruption to financial markets.

Montagu Norman is no doubt spinning in his grave. But increased transparency has made us all better off.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Federal Reserve, Washington, by Rdsmith4. CC-BY-SA-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) European Central Bank, by Eric Chan. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Transparency at the Fed appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 7/2/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Business & Economics,

eurozone,

liberal party,

Richard S. Grossman,

Irish Potato Famine,

Economic Policy with Richard S. Grossman,

Nine Economic Disasters,

corn laws,

euro crisis,

john russell,

potato famine,

robert peel,

Books,

History,

Economics,

Current Affairs,

economy,

Europe,

famine,

inflation,

irish famine,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

currency,

Add a tag

By Richard S. Grossman

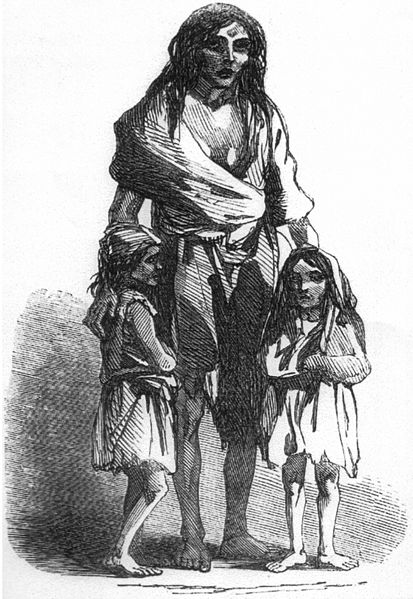

What do the Irish famine and the euro crisis have in common?

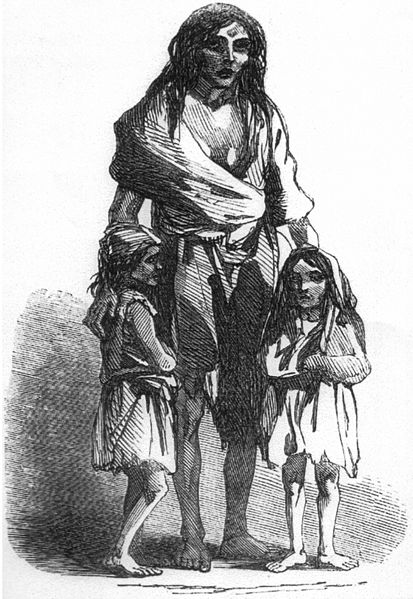

The famine, which afflicted Ireland during 1845-1852, was a humanitarian tragedy of massive proportions. It left roughly one million people—or about 12 percent of Ireland’s population—dead and led an even larger number to emigrate.

The euro crisis, which erupted during the autumn of 2009, has resulted in a virtual standstill in economic growth throughout the Eurozone in the years since then. The crisis has resulted in widespread discontent in countries undergoing severe austerity and in those where taxpayers feel burdened by the fiscal irresponsibility of their Eurozone partners.

Despite these widely differing circumstances, these crises have an important element in common: both were caused by economic policies that were motivated by ideology rather than cold hard economic analysis.

The Irish famine came about when the infestation of a fungus, Phythophthora infestans, led to the decimation of the potato crop. Because the Irish relied so heavily on potatoes for food, this had a devastating effect on the population.

At the time of the famine, Ireland was part of the United Kingdom. Britain’s Conservative government of the time, led by Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, swiftly undertook several measures aimed at alleviating the crisis, including arranging a large shipment of grain from the United States in order to offer temporary relief to those starving in Ireland.

More importantly, Peel engineered a repeal of the Corn Laws, a set of tariffs that kept grain prices high. Because the Corn Laws benefitted Britain’s landed aristocracy—an important constituency of the Conservative Party, Peel soon lost his job and was replaced as prime minister by the Liberal Party’s Lord John Russell.

Russell and his Liberal Party colleagues were committed to an ideology that opposed any and all government intervention in markets. Although the Liberals had supported the repeal of the Corn Laws, they opposed any other measures that might have alleviated the crisis. Writing of Peel’s decision to import grain, Russell wrote: “It must be thoroughly understood that we cannot feed the people. It was a cruel delusion to pretend to do so.”

Contemporaries and historians have judged Russell’s blind adherence to economic orthodoxy harshly. One of the many coroner’s inquests that followed a famine death recommended that a charge of willful murder be brought against Russell for his refusal to intervene in the famine.

The euro was similarly the result of an ideologically based policy that was not supported by economic analysis.

In the aftermath of two world wars, many statesmen called for closer political and economic ties within Europe, including Winston Churchill, French premiers Edouard Herriot and Aristide Briand, and German statesmen Gustav Stresemann and Konrad Adenauer.

The post-World War II response to this desire for greater European unity was the European Coal and Steel Community, the European Economic Community, and eventually, the European Union each of which brought increasingly closer economic ties between member countries.

By the 1990s, European leaders had decided that the time was right for a monetary union and, with the Treaty of Maastricht (1993), committed themselves to the establishment of the euro by the end of the decade.

The leap from greater trade and commercial integration to a monetary union was based on ideological, rather than economic reasoning. Economists warned that Europe did not constitute an “optimal currency area,” suggesting that such a currency union would not be successful. The late German-American economist Rüdiger Dornbusch classified American economists as falling into one of three camps when it came to the euro: “It can’t happen. It’s a bad idea. It won’t last.”

The historical experience also suggested that monetary unions that precede political unions, such as the Latin Monetary Union (1865-1927) and the Scandinavian Monetary Union (1873-1914), were bound to fail, while those that came after political union, such as those in the United States in 18th century, Germany and Italy in the 19th century, and Germany in the 20th century were more likely to succeed. The various European Monetary System arrangements in the 1970s, none of which lasted very long, also provided evidence that European monetary unification was not likely to be smooth.

Concluding that it was a mistake to adopt the euro in the 1990s is, of course, not the same thing as recommending that the euro should be abandoned in 2014. German taxpayers have every reason to resent the cost of supporting their economically weaker—and frequently financially irresponsible—neighbors. However, Germany’s prosperity rests in large measure on its position as Europe’s most prolific exporter. Should Germany find itself outside the euro-zone, using a new, more expensive German mark, German prosperity would be endangered.

What we can say about the response to the Irish Famine and the decision to adopt the euro is that they were made for ideological, rather than economic reasons. These—and other episodes during the last 200 years—show that economic policy should never be made on the basis of economic ideology, but only on the basis of cold, hard economic analysis.

Richard S. Grossman is a Professor of economics at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, USA and a visiting scholar at Harvard University’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science. His most recent book is WRONG: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them. His homepage is RichardSGrossman.com, he blogs at UnsettledAccount.com, and you can follow him on Twitter at @RSGrossman. You can also read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Irish potato famine, Bridget O’Donnel. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Sir Robert Peel, portrait. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The danger of ideology appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 7/1/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Law,

Videos,

Video,

Current Affairs,

money,

Multimedia,

usa,

debt,

economy,

Greece,

rosa,

debt management,

*Featured,

currency,

debt crisis,

commercial law,

lee c bucheit,

sovereign debt,

Soveriegn Debt Management,

buchheit,

sovereign,

lastra,

ver0jqrznm,

borrow”,

buchheit’s,

Add a tag

From Greece to the United States, across Europe and in South America – sovereign debt and the shadow of sovereign debt crisis have loomed over states across the world in recent decades. Why is sovereign debt such a pressing problem for modern democracies? And what are the alternatives? In this video Lee Buchheit discusses the emergence of sovereign debt as a global economic reality. He critiques the relatively recent reliance of governments on sovereign debt as a way to manage budget deficits. Buchheit highlights in particular the problems inherent in expecting judges to solve sovereign debt issues through restructuring. As he explores the legal, financial and political dimensions of sovereign debt management, Buchheit draws a provocative conclusion about the long-term implications of sovereign debt, arguing that “what we have done is to effectively preclude the succeeding generations from their own capacity to borrow”.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Buchheit speaks at the launch of Sovereign Debt Management, edited by Rosa M. Lastra and Lee C. Buchheit.

Lee C. Buchheit is a partner based in the New York office of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP. Dr Rosa María Lastra, who introduces Buchheit’s lecture, is Professor in International Financial and Monetary Law at the Centre for Commercial Law Studies (CCLS), Queen Mary, University of London.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via

email or

RSS.

The post Sovereign debt in the light of eternity appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 4/3/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Current Affairs,

*Featured,

currency,

Business & Economics,

Bretton Woods,

China bashing,

China exchange rate,

Chinese economy,

hot money,

labor costs,

Rise of China,

trade surplus,

Unloved Dollar Standard,

yuan-dollar rate,

yuan,

saving—surplus,

Add a tag

By Ronald McKinnon

In late February, the slow appreciation of China’s currency was interrupted by a discrete depreciation from 6.06 to 6.12 yuan per dollar. Despite making front page headlines in the Western financial press, this 1% depreciation was too small to significantly affect trade in goods and services—and hardly anything compared to how floating exchange rates change among other currencies. Why then the great furor? And what should China’s foreign exchange policy be?

Foreign governments and influential pundits continually pressure China to appreciate the yuan in the mistaken belief that China’s large trade—read: saving—surplus would decline. This pressure is often called China bashing. And since July 2008 when the exchange rate was 8.28 yuan/dollar (and had been held constant for 10 years), the People’s Bank of China has more or less complied. So even the small depreciation was upsetting to foreign China bashers.

But an unintended consequence of sporadically appreciating the yuan, even by very small amounts, is (was) to increase the flow of “hot” money into China. With US short-term interest rates near zero, and the “natural” rate of interbank interest rate in the more robustly growing Chinese economy closer to 4%, an expected rate of yuan appreciation of just 3% leads to an “effective” interest rate differential of 7%. This profit margin is more than enough to excite the interest of carry traders: speculators who borrow in dollars, and try to circumvent the China’s exchange controls on financial inflows, to buy yuan assets. True, the 4% interest differential alone is enough to bring hot money into China (and into other emerging markets). But the monetary control problem is more acute when foreign economists and politicians complain that the Chinese currency is undervalued and the source of China’s current account surplus.

However, China’s current account surplus with the United States does not indicate that the yuan is undervalued. Rather the trade imbalance reflects a big surplus of saving over investment in China, and a bigger saving deficiency—as manifest in the ongoing fiscal deficit—in the United States. Indeed, the best index for tradable goods prices in China, the WPI, has been falling at about 1.5% per year—as if the yuan were slightly overvalued.

Although movements in exchange rates are not helpful in correcting net trade (saving) imbalances between highly open economies, they can worsen hot money flows. Thus, to minimize hot money flows, the People’s Bank of China (PBC) should simply stabilize the central rate at whatever it is today, say 6.1 yuan per dollar, to dampen the expectation of future appreciation. Upsetting the speculators by introducing more uncertainty into the exchange system, as with the temporary mini devaluation of the yuan in late February, is a distant second-best strategy for China to minimize inflows of hot money.

In addition, there is a second, less well recognized argument for keeping the yuan-dollar rate stable. In a rapidly growing economy like China’s with large gains in labor productivity, wage levels become quite flexible because wage growth is so high. That is, if wages grow at 15% instead of 10% per year (roughly the range of wage growth in China in recent years), the wage level moves up much faster. But wage growth better reflects productivity gains if the yuan/dollar rate is kept stable. If an employer (particularly in an export industry) fears future yuan appreciation, he will hesitate to increase workers’ pay by the full increase in their productivity. Otherwise, the firm could go bankrupt if the yuan did appreciate.

In addition, there is a second, less well recognized argument for keeping the yuan-dollar rate stable. In a rapidly growing economy like China’s with large gains in labor productivity, wage levels become quite flexible because wage growth is so high. That is, if wages grow at 15% instead of 10% per year (roughly the range of wage growth in China in recent years), the wage level moves up much faster. But wage growth better reflects productivity gains if the yuan/dollar rate is kept stable. If an employer (particularly in an export industry) fears future yuan appreciation, he will hesitate to increase workers’ pay by the full increase in their productivity. Otherwise, the firm could go bankrupt if the yuan did appreciate.

Thus, to better balance international competitiveness by having Chinese unit labor costs approach those in the mature industrial economies, China should encourage higher wage growth by keeping the yuan-dollar rate stable and so take away the threat of future appreciation. Notice that in the mature, not to say stagnant, industrial economies, macroeconomists typically assume that wages are inflexible or “sticky”. They then advocate flexible exchange rates to overcome wage stickiness. But for high-growth China, flexible wages become the appropriate adjusting variable if the exchange rate is stable. Unlike exchange appreciation, wages can grow quickly without attracting unwanted hot money inflows.

China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) has now accumulated over $4 trillion in exchange reserves because of continual intervention to buy dollars by the PBC. This stock of “reserves” is far in excess of any possible Chinese emergency need for international money, i.e., dollars. In addition, the act of intervention itself often threatens to undermine the PBC’s monetary control. When it buys dollars with yuan, the supply of base money in China’s domestic banking system expands and threatens price inflation or bubbles in asset prices such as real property.

Thus to sterilize the domestic excess monetary liquidity from foreign exchange interventions, the PBC frequently sells central bank bonds to the commercial banks—or raises the required reserves that the commercial banks must hold with the central bank—in order to dampen domestic credit expansion. Both sterilization techniques undermine the efficiency of the commercial banks’ important role as financial intermediaries between domestic savers and investors. Currently in China, this sterilization also magnifies the explosion in shadow banking by informal institutions not subject to reserve or capital requirements, or interest rate ceilings.

To better secure domestic monetary control, why doesn’t the PBC just give up intervening to set the yuan/dollar rate and let it float, i.e., be determined by the market? If the PBC withdrew from the foreign exchange market, the yuan would begin to appreciate without any well-defined limit. The upward pressure on the yuan has two principal sources:

- Extremely low, near-zero, short interest rates in the United States, United Kingdom, the European Union, and Japan. With the more robust Chinese economy having naturally higher interest rates, unrestricted hot money would flow into China. Once the yuan began to appreciate, carry traders would see even greater short-term profits from investing in yuan assets.

- China is an immature international creditor with underdeveloped domestic financial markets. Although China has a chronic saving (current account) surplus, it cannot lend abroad in its own currency to finance it.

Why not just lend abroad in dollars? Private (nonstate) banks, insurance companies, pension funds and so on, have a limited appetite for building up liquid dollar claims on foreigners when their own liabilities—deposits, insurance claims, and pension obligations— are in yuan. Because of this potential currency mismatch in private financial institutions, the PBC (which does not care about exchange rate risk) must step in as the international financial intermediary and buy liquid dollar assets on a vast scale as the counterpart of China’s saving surplus.

Even if there was no hot money inflow into China, the yuan would still be under continual upward pressure in the foreign exchanges because of China’s immature credit status (under the absence of a natural outflow of financial capital to finance the trade surplus). That is, foreigners remain reluctant to borrow from Chinese banks in yuan or issue yuan denominated bonds in Shanghai. This reluctance is worsened because of the threat from China bashing that the yuan might appreciate in the future. Thus the PBC has no choice but to keep intervening in the foreign exchanges to set and (hopefully) stabilize the yuan/dollar rate.

Superficially, the answer to China’s currency conundrum would seem be to fully liberalize its domestic financial markets by eliminating interest rate restrictions and foreign exchange controls. Then China could become a mature international creditor with natural outflows of financial capital to finance its trade surplus. Then the PBC need not continually intervene in the foreign exchanges.

This “internationalization” of the yuan may well resolve China’s currency conundrum in the long run. However, it is completely impractical—and somewhat dangerous—to try it in the short run. With near-zero short term interest rates in the mature industrial world, China would be completely flooded out by inflows of hot money, which would undermine the PBC’s monetary control and drive China’s domestic interest rates down much too far. China is in a currency trap. But within this dollar trap, China has shown that its GDP can grow briskly with even more rapid growth in wages—as long as the yuan-dollar rate remains reasonably stable. And China’s government must recognize that there is no easy way to spring the trap.

Ronald McKinnon is the William D. Eberle Professor Emeritus of International Economics at Stanford University, where he has taught since 1961. For a more comprehensive analysis of how the world dollar standard works, and China’s ambivalent role in supporting it, see Ronald McKinnon’s The Unloved Dollar Standard from Bretton Woods to the Rise of China, Oxford University Press (2013), and the Chinese translation from China Financial Publishing House (2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Beijing skyline and traffic jam on ring road, China. Photo by coryz, iStockphoto.

The post China’s exchange rate conundrum appeared first on OUPblog.

Question of the day (from the Story Charmer) is: what are your currencies, what do you value? I often think about what my own value is to my family. Once a person in this country retires from her day job, she begins to lose value like a new car driven off the lot. When I last worked a full-time job I made the most money I had ever made in my lifetime of work, and I began working at age 13. I worked full-time from age 17 on. When I returned to school at age 29 to go to university, I quizzed out of freshman year entirely, and worked 3-5 part-time jobs while going to school more than full-time so I could finish as quickly as possible and owe as little as possible.

All throughout my lifetime I gave presents, loans, supported as many people as I could, and managed to save money for retirement as well. I do not regret a single cent I ever gave or loaned or spent. The recession ate up more than I spent, and I regretted not having spent more so Bernie Madoff didn't get that little bit of my retirement savings. He wasn't who I loved.

So nowadays my currency, my personal value is no longer cash money. I give what I can of myself. And still sometimes, I feel a bit useless. I recognize how much perkier I am when someone asks for my help. Whether it is to show them how to sew on a button (my grandson), or to edit a script, sit with a dog, or work at one of my part-time jobs, I perk up more than when I'm working on my own writing projects. I enjoy helping others, and may find more value in being helpful than I do in my own creativity.

These are deep thoughts and not all that pleasant, to be honest. I find great conflict here. Isn't my writing as valuable as helping someone else? Do you suffer from this syndrome? Is it a syndrome? Is it even a problem?

Characters all have needs and desires that form their “currency.” A character’s currency might be safety, money, esteem, physical objects or spiritual well-being. Some desire closeness; others desire space. Learning a character’s “currency” is the key other characters need to influence them and build a relationship with them.

If someone keeps trying to motivate or influence your character by promising or threatening them with things they don’t want or don’t care about, their efforts will fail. Characters with opposing currencies have a difficult time building a relationship, a friendship or a working partnership.

An antagonist who threatens people with things they aren’t afraid of fails in his scene objective. An antagonist who bribes his henchmen with things they don’t want also fails in his scene objective.

If Dick is motivated by a job well done, then self-esteem is its own reward. Dick might react positively to praise, or find it uncomfortable. If Dick is performing a task for the self-satisfaction of seeing it done, when Sally heaps praise on him for it, it won’t mean much. His lack of reaction can confuse and annoy Sally. Especially if Dick counters the praise with, “I didn’t do it for you.” Those are fighting words. Sally feels her gift of praise is rejected and her feelings are hurt. That will either throw her into passive mode or aggressive mode.

Whenever Sally feels like she is giving Dick something, even if it is something Dick neither wants, needs nor values, she expects esteem in return. Dick, not understanding her currency, won’t give it to her. He will just be annoyed that he was given something he didn’t want, need or value. In order for them to mend fences, Sally would have to come to grips with the fact that not everyone wants, needs or values what she wants, needs and values. Dick would have to learn how to graciously accept something he didn’t want because Sally was exhibiting generosity of spirit in giving it. To go forward in a healthy manner, they would both have to learn to communicate their wants, needs and currency in a calm, rational way. That rarely happens. Characters rarely become so self-aware that their psychological buttons aren’t pushed. That's why we have fiction ... and reality television.

The esteem of others can be a reward that re-enforces Dick's scene or overall story goal. This is great if Dick is building a house for Habitat for Humanity. Not so good if he is building a robot that will take over the planet.

If Sally does something with the expectation of being praised and praise is withheld, she may get mad. She may be tempted to get even. She might undo her efforts in retaliation for not receiving the accolades she hoped for. She may be driven to petty acts of spite or refuse to cooperate further. This dynamic plays out in couples, families and offices all over the globe. It plays out in classrooms, sports teams, social clubs and PTAs.

0 Comments on Conflicts of Currency as of 1/1/1900

By: Lauren,

on 1/7/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

euro,

bonds,

fiscal crisis,

*Featured,

barry eichengreen,

central bank,

currency,

exorbitant privilege,

monetary,

exorbitant,

Economics,

Finance,

dollar,

Add a tag

By Barry Eichengreen

If the euro’s crisis has a silver lining, it is that it has diverted attention away from risks to the dollar. It was not that long ago that confident observers were all predicting that the dollar was about to lose its “exorbitant privilege” as the leading international currency. First there was financial crisis, born and bred in the United States. Then there was QE2, which seemed designed to drive down the dollar on foreign exchange markets. All this made the dollar’s loss of preeminence seem inevitable.

The tables have turned. Now it is Europe that has deep economic and financial problems. Now it is the European Central Bank that seems certain to have to ramp up its bond-buying program. Now it is the euro area where political gridlock prevents policy makers from resolving the problem.

In the U.S. meanwhile, we have the extension of the Bush tax cuts together with payroll tax reductions, which amount to a further extension of the expiring fiscal stimulus. This tax “compromise,” as it is known, has led economists to up their forecasts of U.S. growth in 2011 from 3 to 4%. In Europe, meanwhile, where fiscal austerity is all the rage, these kind of upward revisions are exceedingly unlikely.

All this means that the dollar will be stronger than expected, the euro weaker. China may have made political noises about purchasing Irish and Spanish bonds, but which currency – the euro or the dollar – do you think prudent central banks will find it more attractive to hold?

There are of course a variety of smaller economies whose currencies are likely to be attractive to foreign investors, both public and private, from the Canadian loonie and Australian dollar to the Brazilian real and Indian rupee. But the bond markets of countries like Canada and Australia are too small for their currencies to ever play more than a modest role in international portfolios.

Brazilian and Indian markets are potentially larger. But these countries worry about what significant foreign purchases of their securities would mean for their export competitiveness. They worry about the implications of foreign capital inflows for inflation and asset bubbles. India therefore retains capital controls which limit the access of foreign investors to its markets, in turn limiting the attractiveness of its currency for international use. Brazil has tripled its pre-existing tax on foreign purchases of its securities. Other emerging markets have moved in the same direction.

China is in the same boat. Ten years from now the renminbi is likely to be a major player in the international domain. But for now capital controls limit its attractiveness as an investment vehicle and an international currency. This has not prevented the Malaysian central bank from adding Chinese bonds to its foreign reserves. It has not prevented companies like McDonald’s and Caterpillar from issuing renminbi-denominated bonds to finance their Chinese operations. But China will have to move significantly further in opening its financial markets, enhancing their liquidity, and strengthening rule of law before its currency comes into widespread international use.

So the dollar is here to stay, more likely than not, if only for want of an alternative.

The one thing that co

In addition, there is a second, less well recognized argument for keeping the yuan-dollar rate stable. In a rapidly growing economy like China’s with large gains in labor productivity, wage levels become quite flexible because wage growth is so high. That is, if wages grow at 15% instead of 10% per year (roughly the range of wage growth in China in recent years), the wage level moves up much faster. But wage growth better reflects productivity gains if the yuan/dollar rate is kept stable. If an employer (particularly in an export industry) fears future yuan appreciation, he will hesitate to increase workers’ pay by the full increase in their productivity. Otherwise, the firm could go bankrupt if the yuan did appreciate.

In addition, there is a second, less well recognized argument for keeping the yuan-dollar rate stable. In a rapidly growing economy like China’s with large gains in labor productivity, wage levels become quite flexible because wage growth is so high. That is, if wages grow at 15% instead of 10% per year (roughly the range of wage growth in China in recent years), the wage level moves up much faster. But wage growth better reflects productivity gains if the yuan/dollar rate is kept stable. If an employer (particularly in an export industry) fears future yuan appreciation, he will hesitate to increase workers’ pay by the full increase in their productivity. Otherwise, the firm could go bankrupt if the yuan did appreciate.