By Tony Hope

Science and morality are often seen as poles apart. Doesn’t science deal with facts, and morality with, well, opinions? Isn’t science about empirical evidence, and morality about philosophy? In my view this is wrong. Science and morality are neighbours. Both are rational enterprises. Both require a combination of conceptual analysis, and empirical evidence. Many, perhaps most moral disagreements hinge on disagreements over evidence and facts, rather than disagreements over moral principle.

Consider the recent child euthanasia law in Belgium that allows a child to be killed – as a mercy killing – if: (a) the child has a serious and incurable condition with death expected to occur within a brief period; (b) the child is experiencing constant and unbearable suffering; (c) the child requests the euthanasia and has the capacity of discernment – the capacity to understand what he or she is requesting; and, (d) the parents agree to the child’s request for euthanasia. The law excludes children with psychiatric disorders. No one other than the child can make the request.

Is this law immoral? Thought experiments can be useful in testing moral principles. These are like the carefully controlled experiments that have been so useful in science. A lorry driver is trapped in the cab. The lorry is on fire. The driver is on the verge of being burned to death. His life cannot be saved. You are standing by. You have a gun and are an excellent shot and know where to shoot to kill instantaneously. The bullet will be able to penetrate the cab window. The driver begs you to shoot him to avoid a horribly painful death.

Would it be right to carry out the mercy killing? Setting aside legal considerations, I believe that it would be. It seems wrong to allow the driver to suffer horribly for the sake of preserving a moral ideal against killing.

Thought experiments are often criticised for being unrealistic. But this can be a strength. The point of the experiment is to test a principle, and the ways in which it is unrealistic can help identify the factual aspects that are morally relevant. If you and I agree that it would be right to kill the lorry driver then any disagreement over the Belgian law cannot be because of a fundamental disagreement over mercy killing. It is likely to be a disagreement over empirical facts or about how facts integrate with moral principles.

There is a lot of discussion of the Belgian law on the internet. Most of it against. What are the arguments?

Some allow rhetoric to ride roughshod over reason. Take this, for example: “I’m sure the Belgian parliament would agree that minors should not have access to alcohol, should not have access to pornography, should not have access to tobacco, but yet minors for some reason they feel should have access to three grams of phenobarbitone in their veins – it just doesn’t make sense.”

But alcohol, pornography and tobacco are all considered to be against the best interests of children. There is, however, a very significant reason for the ‘three grams of phenobarbitone’: it prevents unnecessary suffering for a dying child. There may be good arguments against euthanasia but using unexamined and poor analogies is just sloppy thinking.

I have more sympathy for personal experience. A mother of two terminally ill daughters wrote in the Catholic Herald: “Through all of their suffering and pain the girls continued to love life and to make the most of it…. I would have done anything out of love for them, but I would never have considered euthanasia.”

But this moving anecdote is no argument against the Belgian law. Indeed, under that law the mother’s refusal of euthanasia would be decisive. It is one thing for a parent to say that I do not believe that euthanasia is in my child’s best interests; it is quite another to say that any parent who thinks euthanasia is in their child’s best interests must be wrong.

To understand a moral position it is useful to state the moral principles and the empirical assumptions on which it is based. So I will state mine.

Moral Principles

- A mercy killing can be in a person’s best interests.

- A person’s competent wishes should have very great weight in what is done to her.

- Parents’ views as to what it right for their children should normally be given significant moral weight.

- Mercy killing, in the situation where a person is suffering and faces a short life anyway, and where the person is requesting it, can be the right thing to do.

Empirical assumptions

- There are some situations in which children with a terminal illness suffer so much that it is in their interests to be dead.

- There are some situations in which the child’s suffering cannot be sufficiently alleviated short of keeping the child permanently unconscious.

- A law can be formulated with sufficient safeguards to prevent euthansia from being carried out in situations when it is not justified.

This last empirical claim is the most difficult to assess. Opponents of child euthanasia may believe such safeguards are not possible: that it is better not to risk sliding down the slippery slope. But the ‘slippery slope argument’ is morally problematic: it is an argument against doing the right thing on some occasions (carrying out a mercy killing when that is right) because of the danger of doing the wrong thing on other occasions (carrying out a killing when that is wrong). I prefer to focus on safeguards against slipping. But empirical evidence could lead me to change my views on child euthanasia. My guess is that for many people who are against the new Belgian law, it is the fear of the slippery slope that is ultimately crucial. Much moral disagreement, when carefully considered, comes down to disagreement over facts. Scientific evidence is a key component of moral argument.

Tony Hope is Emeritus Professor of Medical Ethics at the University of Oxford and the author of Medical Ethics: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

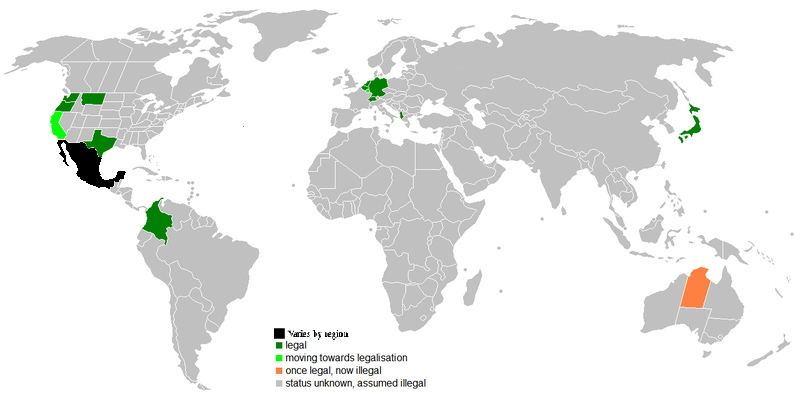

Image credit: Legality of Euthanasia throughout the world By Jrockley. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Morality, science, and Belgium’s child euthanasia law appeared first on OUPblog.