Title: Mango, Abuela and Me Author: Meg Medina Illustrator: Angela Dominguez Publisher: Candlewick Press, 2015 Themes: love, learning new language, making friends Awards: Belpre (Author and illustrator) Honor Books, 2016 Ages: 3-7 Opening: SHE COMES TO US in winter, leaving behind her sunny house that rested between two snaking rivers. … Continue reading

Add a CommentViewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: language learning, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

Blog: Miss Marple's Musings (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Meg Medina, Perfect Picture Book Friday, WNDB, Diversity Day 2016, Belpre (Author) Honor Books 2016, Mango Abuela and Me, Book recommendation, Spanish, grandmothers, teaching resources, language learning, Angela Dominguez, Add a tag

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Books, grammar, Language, Linguistics, Latin, language learning, Romance language, *Featured, Classics & Archaeology, Language Studies, Language Education, Latin and Romance Languages, Latin Language, Latin: A Linguistics Introduction, Modern Linguistics, Norma Schifano, Renato Oniga, Romance Languages, Study of Grammar, Study of Language, Universal Grammar, Add a tag

The development of linguistics as a scientific discipline is one of the greatest achievements of contemporary thought, as it has led to the discovery of some fundamental principles about the functioning of language. However, most of its recent discoveries have not yet reached the general audience of educated people beyond the specialists. Scholars of classics, in particular, have found it difficult to become involved in the debate, since many recent studies in linguistics have been driven by the necessity to free themselves from the subordination to Latin grammar and have put into question the validity of certain aspects of traditional grammar.

As a consequence, progress made by contemporary linguistics has paradoxically had a negative rather than positive effect on the teaching of Latin. Although traditional grammars are now outdated, a suitable replacement has not yet been offered and a widespread scepticism has forced many to keep relying on old fashioned textbooks.

In order to overcome this undesirable state of affairs, it is desirable to bring Latin grammar back to its original high-level scientific conception, going beyond a prescriptive attitude and restoring the original theoretical tension. Although many branches of contemporary linguistics are potentially suited to fulfil this objective, none of them have been fully exploited in teaching yet. Their advantage over traditional approaches lies in their ability to satisfy the same needs as traditional analytical and philosophical Latin grammar, exploiting – at the same time – new methods, which are suitable to formulate more accurate analyses and theoretical generalizations.

Latin grammar should be presented as an activity which raises the linguistic awareness of its readers, using the most recent tools of modern linguistics. This should not be limited to the traditional Indo-European historical perspective, but includes the comparison of different languages and the attempt to represent the way in which grammar rules are codified in the mind.

The hypothesis is that there exists a language faculty underlying all languages, known as Universal Grammar (UG), i.e. a system of variable and invariable factors internalized in the speaker’s mind, which constitutes the basis of the grammar of each language. Understanding the contents of UG amounts to understanding those linguistic phenomena that are common to all languages. In this perspective, it is possible to develop a new method of teaching Latin, which aims at strengthening the cognitive skills of the learner’s mind. This method consists in overcoming the rigidity of a purely normative conception of grammatical rules, in order to make them explicit in a synchronic formal way and thus formulate hypotheses about the mental mechanisms that generate them. This method is an updated enhancement of the old conception of grammatical studies known as progymnasmata, i.e. “gymnastics of the mind,” which introduces the reader to the world of classical scholarship.

On the basis of some recent discoveries made by the neurosciences, it is possible to formulate grammatical rules that represent a better approximation of the implicit and explicit mental operations carried out by the language learner. The desired effect is the activation of the appropriate areas of the brain, i.e. the ones which are naturally devoted to the processing of linguistic information, thus rendering the process of language acquisition faster and more natural. Indeed, a vast number of recent studies have shown that language learning strongly relies on a constant and unconscious comparison between the second language (L2) and the learner’s mother tongue. By comparing linguistic phenomena across distinct languages and by interpreting the results with updated theoretical tools, we intend to underlie the deep similarities among languages rather than their superficial differences. This new teaching perspective represents a fundamental advantage for learners, who can focus their attention on the limits of linguistic variation, making their acquisitional task more feasible. In particular, by overtly reflecting on language and comparing L2 grammars to the structures of the mother tongue, the study of Latin becomes more stimulating and active.

Moreover, as students become aware of the difference between a “mistake”, as banned from the standard language, and linguistic “agrammaticality” (i.e. an option which is disallowed by the deep structure of the language), they become more critical and aware of the level of their written and oral performance in their mother tongue. From this perspective, it is clear that the study of Latin contributes to the overall linguistic education of learners, and not only to the training of those interested in classical studies. Students should no longer learn by heart the obscure rules of school grammars, often rooted on misconceptions, but they should instead explore the discoveries of centuries of classical scholarship in order to actively work out how languages function and change. In particular, they should focus their attention on the aspects of the targeted language they already know, before exploring the points of divergence from their mother tongue. Thanks to this revised methodology, the study of Latin loses any passive connotation and becomes an activity which enhances linguistic awareness, meta-linguistic competence, as well as critical thought.

The post The role of grammar for the teaching of Latin appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: oxfordwords blog, Dictionaries & Lexicography, Arabic language, Oxford Arabic Dictionary, Oxford Dictionaries Arabic, Semitic languages, Tressy Arts, Language, arabic, linguistics, language learning, *Featured, Add a tag

To celebrate the launch of our new Oxford Arabic Dictionary (in print and online), the Chief Editor, Tressy Arts, explains why she decided to become an Arabist.

When I tell people I’m an Arabist, they often look at me like they’re waiting for the punchline. Some confuse it with aerobics and look at me dubiously — I don’t quite have the body of a dance instructor. Others do recognize the word “Arabic” and look at me even more dubiously — “What made you decide to study that!?”

Well, my case is simple, if probably not typical. In the Netherlands, where I grew up, you can learn a lot of languages in secondary school, and I tried them all. So when the time came to choose a university study, “a language that isn’t like the others” seemed the most attractive option — and boy, did Arabic deliver.

Squiggly lines and dots?

It started with the script. A lot of people are put off by Arabic’s script, because it looks so impenetrable — all those squiggly lines and dots. At least if you are unfamiliar with Italian you can still make out some of the words. However, the script is really perfectly simple, and anyone can learn it in an hour or two. Arabic has 28 letters, some for sounds that don’t exist in English (and learning to pronounce these can be tricky and cause for much hilarity, like the ‘ayn which I saw most accurately described as “imagine you are at the dentist and the drill touches a nerve”), some handily combining a sound for which English needs two letters into one, like th and sh. Vowels aren’t usually written, only consonants. The dots are to distinguish between letters which have the same basic shape. And the reason it all looks so squiggly is that letters within one word are joined up, like cursive. Once you can see that, it all becomes a lot more transparent.

So once we mastered the script, after the first day of university, things got really interesting. The script unlocked a whole new world of language, and a fascinating language it was. Arabic is a Semitic language, which places it outside the Indo-European language family, and Semitic languages have some unique properties that I had never imagined.

Root-and-pattern

For example, Arabic (and other Semitic languages) has a so-called “root-and-pattern” morphology. This means that every word is built up of a root, usually consisting of three consonants, which carries the basic meaning of that word; for example the root KTB, with basic meaning “writing”, or DRS “studying”. This root is then put in a pattern consisting of vowels and affixes, which manipulate its meaning to form a word. For example, *aa*i* means “the person who does something”, so a KaaTiB is “someone who writes”: a writer; and a DaaRiS is “someone who studies”: a researcher. Ma**a* means “the place where something takes place”, so a maKTaB is an office, a maKTaBa a library or bookshop, a maDRaSa a school.

This makes learning vocabulary both harder and easier. On the one hand, in the beginning all words sound the same — all verbs have the pattern *a*a*a: KaTaBa, BaHaTHa, DaRaSa, HaDaTHa, JaMaʿa — and you may well get utterly confused. But after a while, you get used to it, and if you encounter a new word and are familiar with the root and recognize the pattern, you can at least make an educated guess at what it might mean.

Keeping things logical . . . usually

Another wonderful aspect of Arabic is that it doesn’t have irregular verbs, unlike, for example, French (I’m looking at you pouvoir). But before you all throw out your French text books and switch to Arabic, let me warn you that there are about 250 different types of regular verb, each of which conjugates into 110 forms. This led to Guy Deutscher remarking, “if the Latin verbal system looked uncomfortably complex, here is an example which makes Latin seem like child’s play: the verbal system of the Semitic languages, such as Arabic, Aramaic and Hebrew.” Fair enough, it’s complex, but it’s all logical, and regular. I, for one, had much less trouble learning these Arabic verbs than the Latin and French ones, simply because there is such an elegant method to them.

There are other aspects of Arabic that are less logical. The numbers, for instance. I won’t go too deep into them, but suffice it to say that if you have three books the three is feminine because books are masculine and if you have three balls it’s vice versa, and then if you have thirteen of something the three is the opposite gender but the ten is the same, the counted word is suddenly singular and for no reason at all the whole lot has become accusative. Then at twenty it all changes again. It’s a wonder the Arab world proved so proficient in mathematics.

Other reasons to learn Arabic

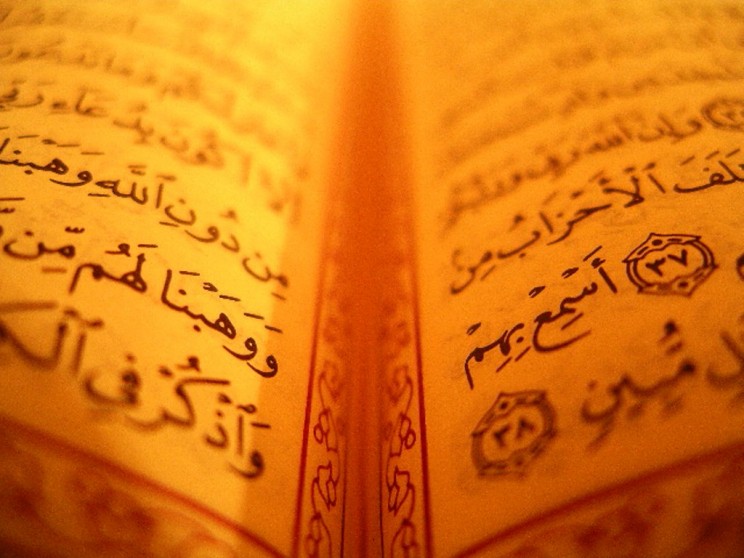

Which leads me to the many other reasons one might want to learn Arabic. I focused on its fascinating linguistics above, because that is my personal favorite field, but there are the cultures steeped in rich history, the fascinating literature ranging from ancient poetry to cutting-edge modern novels, and of course the fact that every Muslim must know at least a little bit of Arabic in order to fulfill their religious duties (shahada, Fatiha, and salat), and for gleaning a deep understanding of the sources of Islam, Arabic is essential. Arabic is also a very wanted skill in many professions, and not just the obvious ones. I recall one of the recruiters at the Arabists’ Career Fair, speaking for a law firm, stating, “We can teach you law. Law is easy. What we need are people with a firm knowledge of Arabic.”

Featured image credit: Learning Arabic calligraphy by Aieman Khimji. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why learn Arabic? appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: YALSA - Young Adult Library Services Association (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: education, Apps, language learning, Teen Services, Add a tag

App of the Week: iTranslate Voice

App of the Week: iTranslate Voice

Cost: $0.99

Platform: Compatible with iPhone 3GS, iPhone 4S, iPod touch 3rd/4th generation, and iPad. Requires iOS 4.3 or later.

I regularly hear the teens in my library grumble about their struggles in foreign language classes and having taken my share of Spanish classes, I can certainly relate. It’s hard to remember a word’s spelling let along the pronunciation when you can only see it written. So when I recently stumbled upon this wonderful app, I knew I could not keep it to myself. iTranslate is definitely not the only language translation app on the market, but I am willing to bet that it very well may be the best.

This app is not only visually appealing with its clean display, but it is also easy to use requiring minimal instruction. The iTranslate app delivers a user- friendly experience with its built- in familiar siri-type voice recognition. Simply speak into the microphone identified with the country flag you choose and listen as you get instant results that are read back in whatever language you prefer. If you prefer to type rather than to speak into the microphone, you may do that as well. This feature may also come in handy if you should need to edit text that the computer misinterpreted.

iTranslate has over 30 different languages to choose from and memorization is a snap with the share, copy, and speak options. The app does require Wi-Fi or 4G to connect, but let’s face it, that is easy enough to come by these days. When I told the teens about this app, they were happy to hear it was under a dollar and would serve as a great study companion for test and projects.

Add a Comment

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: cute, fonts, art, Leisure, asian american, arial, healthcare reform, *Featured, paper tigers, kittens, unshelved, tote bag, tote, language learning, helvetica, smokers, buzzfeed, crashing, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, vol1brooklyn, ironicsans, hardest language, Add a tag

Tweet

This girl is reading the entire Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act out loud. [Act of Law]

Why no smoking signs actually ENCOURAGE smokers to light up [Daily Mail]

Think there’s no point in keeping print books around? I respectfully disagree. [Unshelved]

Here are some kitties crashing into each other. [YouTube]

100,000 staples arranged over 40 hours and other awesome staple art [NextWeb]

What does your literary tote bag say about you? [Vol1Brooklyn]

QUIZ: Can you tell Arial from Helvetica? [Ironicsans]

INFOGRAPHIC: The hardest languages to learn [Column Five]

This article on “Asian-American overachievers” is certainly creating a stir. [NYMag]

Incredible photos of the Great Flood of 1927 [Buzzfeed]

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Religion, Education, grammar, India, school house rock, buckets, ohio, Babar, noun, language learning, Dennis Baron, ganesh, A Better Pencil, *Featured, Lexicography & Language, animal vegetable mineral, Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

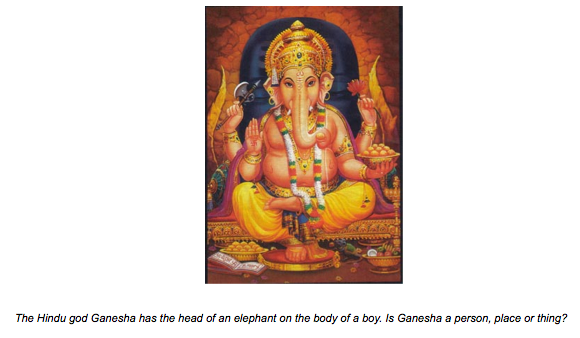

Everybody knows that a noun is the name of a person, place, or thing. It’s one of those undeniable facts of daily life, a fact we seldom question until we meet up with a case that doesn’t quite fit the way we’re used to viewing things.

That’s exactly what happened to a student in Ohio when his English teacher decided to play the noun game. To the teacher, the noun game seemed a fun way to take the drudgery out of grammar. To the student it forced a metaphysical crisis. To me it shows what happens when cultures clash and children get lost in the tyranny of school. That’s a lot to get from a grammar game.

Anyway, here’s how you play. Every student gets a set of cards with nouns written on them. At the front of the classroom are three buckets, labeled “person,” “place,” and “thing.” The students take turns sorting their cards into the appropriate buckets. “Book” goes in the thing bucket. “city” goes in the place bucket. “Gandhi” goes in the person bucket.

Ganesh had a card with “horse” on it. Ganesh isn’t his real name, by the way. It’s actually my cousin’s name, so I’m going to use it here.

You might guess from his name that Ganesh is South Asian. In India, where he had been in school before coming to Ohio, Ganesh was taught that a noun named a person, place, thing, or animal. If he played the noun game in India he’d have four buckets and there would be no problem deciding what to do with “horse.” But in Ohio Ganesh had only three buckets, and it wasn’t clear to him which one he should put “horse” in.

In India, Ganesh’s religion taught him that all forms of life are continuous, interrelated parts of the universal plan. So when he surveyed the three buckets it never occurred to him that a horse, a living creature, could be a thing. He knew that horses weren’t people, but they had more in common with people than with places or things. Forced to choose, Ganesh put the horse card in the person bucket.

Blapp! Wrong! You lose. The teacher shook her head, and Ganesh sat down, mortified, with a C for his efforts. This was a game where you got a grade, and a C for a child from a South Asian family of overachievers is a disgrace. So his parents went to talk to the teacher.

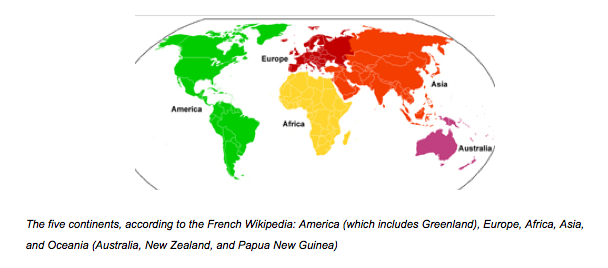

It so happens that I’ve been in a similar situation. We spent a year in France some time back, and my oldest daughter did sixth grade in a French school. The teacher asked her, “How many continents are there?” and she replied, as she had been taught in the good old U.S. of A., “seven.” Blaap! Wrong! It turns out that in France there are only five.

So old dad goes to talk to the teacher about this. I may not be able to remember the seven dwarfs, but I rattled off Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, Antarctica, North America, and South America. The teacher calmly walked me over to the map of the world. Couldn’t I see that Antarctica was an uninhabited island? And couldn’t I see that North and South America were connected? Any fool could see as much.

At that point I decided not to press the observation that Europe and Asia were also connected. Some things are not worth fighting for when you’re fighting your child’s teacher.