By Rebecca Rossen

On 27 February 1932, the American modern dancer Pauline Koner presented a concert at New York City’s Town Hall. For the occasion, Koner, who was Jewish, premiered Chassidic Song and Dance, a solo in which she portrayed a young Hasidic Jew. Her characterization of an Eastern European Jew was not so different from the other exotics that constituted Koner’s repertory in the 1930s. Indeed, aided by vibrant costumes (and her mother, who would assist in swift costume changes backstage), the soloist would effortlessly transform herself into an array of foreign types—Hindu goddess, Javanese temple dancer, Andalusian maiden, Italian signorina. Yet Chassidic Song and Dance offered a critical distinction. In all her other solos, Koner portrayed female characters; in Chassidic Song and Dance, she presented herself as a boy—in Hasidic drag.

Interestingly, Koner was not the only Jewish female dancer performing in Hasidic drag on New York City stages and screens in the 1920s and 1930s. In Bar Mitzvah (Chassidic) (1929), Belle Didjah depicted an Orthodox youth on the verge of manhood; Dvora Lapson created a number of Hasidic solos including Yeshiva Bachur (1931), Beth Midrash (1936), and The Jolly Hassid (1937); and Benjamin Zemach outfitted a cast of male and female dancers in Hasidic garb for a 1931 concert. The most famous Jewish drag performer was Molly Picon, a seminal figure in Yiddish theater and film who frequently cross-dressed in such Second Avenue stage hits as Yonkele (1922–25) and the films Ost und West (1923) and Yidl Mitn Fidl (1937), presaging Barbra Streisand’s Yeshiva “boy” in Yentl (1983).

Belle Didjah in Bar Mitzvah (1929). Photograph: Maurice Goldberg. Courtesy of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations and the Maurice Goldberg Estate.

Why were these women drawn to Hasidism? Dance was an acceptable form of expression and exaltation in Hasidism. Thus, it makes sense that Jewish female choreographers working in American concert dance would look to Hasidism as a source for inventing modern dances on Jewish themes. However, each of these performers had different relationships to Judaism and Jewish culture, and their identities as Jewish women impacted how they represented Jewishness in performance.

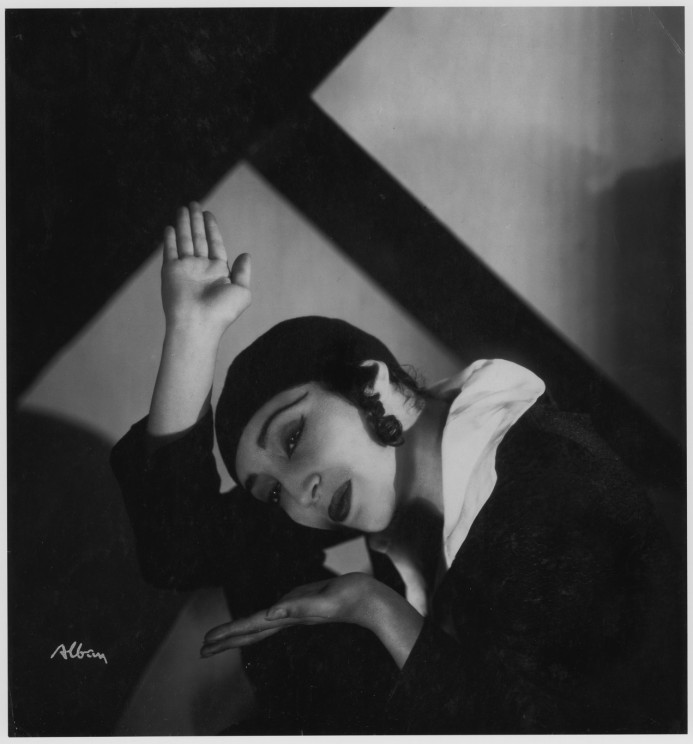

For Koner, who had grown up in a secular home, Judaism was foreign and mysterious. In her autobiography, she likened her occasional childhood trips with her grandfather to a Lower East Side synagogue to visiting a distant land: “To me it was all wondrous theater.” Koner’s approach to representing ethnic material on the American concert stage was to transform it through creative interpretation and invention or, as she explained it, to capture “the flavor rather than the fact.” The actual choreography of Chassidic Song and Dance is not documented, though a stunning photograph of the dancer still exists, depicting her as a Hasidic boy with peyes (side curls), black cap, and black suit. In it, the dancer’s vivid features are highlighted by makeup and her body is positioned against a backdrop of angular shadows. Koner made the Hasidic Jew soulful, yet glamorous. At the same time, by performing so many ethnic types on one program, she suggested that these characterizations were all an act. To a certain degree, the choreographer represented the Hasidic boy, the Hindu goddess, and the Javanese temple dancer in the same way—from a distance, reinforcing her distinction from all the exotics in her repertory. She could portray the Jew, but Jewishness did not define her—she could put it on and take it off at will (or through swift costume changes between acts).

Pauline Koner in Chassidic Song and Dance (1931). Photograph: Aram Alban. Courtesy of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

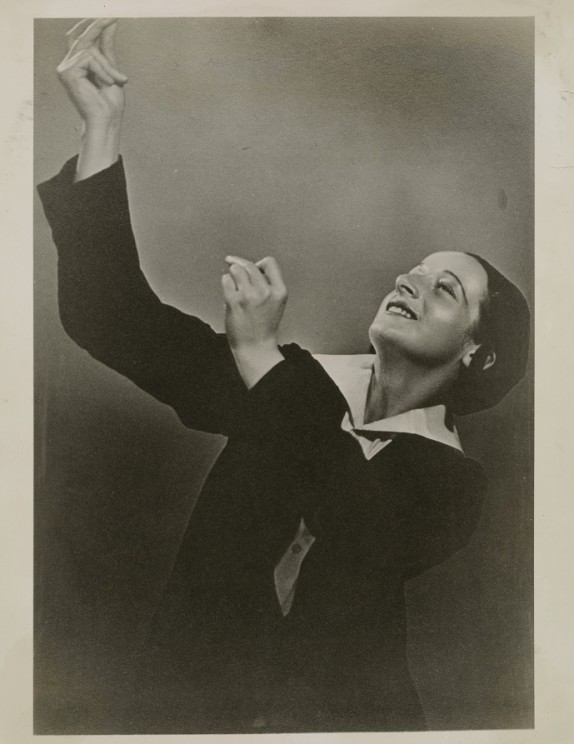

Unlike Pauline Koner, Dvora Lapson’s deep knowledge of Hasidic culture and dance stemmed from extensive ethnographic research that she conducted both in her native New York City and in Poland, where she traveled in 1937 only three years before the Warsaw ghetto was established, after which Poland’s Jewish population was virtually annihilated. Proudly describing herself as a “Jewish dance mime” and a “pioneer of the new Jewish dance,” Lapson wrote that her dance “compositions not only mirror and reflect Jewish life and folklore but present a keen commentary upon them.” In fact, Lapson’s lifelong dedication to Jewish dance would lead Jerome Robbins to hire her as a dance consultant for Fiddler on the Roof. Lapson boasted a vast repertory of Jewish dances in the 1930s, many of which were on Hasidic themes. Photographs of the dancer demonstrate that she was every bit as glamorous as Koner, though Lapson did not exoticize Jewish characters. On the contrary, Lapson believed that dance had the potential to instill pride in American Jews about their heritage and combat anti-Semitism. As she said to an interviewer in 1938, “I want the Gentile as well to find something in my work which makes him more sympathetic and appreciative of my race.”

Dvora Lapson most likely in Beth Midrash (House of Study) (1936). Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations and Beril Lapson.

It is significant that Hasidic drag thrived on the American concert stage during the 1920s and 1930s. By the late 1920s, American modern dance had already emerged as field in which female artists were making great strides by creating dances that portrayed women as autonomous subjects. When they commanded the stage as solo artists, female performers also asserted their ability to play an active role in American society. While Lapson’s dances aimed to increase American audiences’ understanding of Jewish culture and traditions, Koner’s Chassidic Song and Dance emphasized Jewish difference. It should be noted, however, that Koner premiered the dance at a benefit supporting the seventh anniversary of the Pioneer Women’s Organization of America, a left-wing association that rebuffed the chauvinism of American Zionism and aimed to educate Jewish women to become equal participants in a just society. Although their approaches were distinct, both Koner and Lapson used dance to intervene in a patriarchal religion that restricted women’s participation in religious and public life. By dancing in drag and by dancing solo, they subtly demanded a platform for women in Jewish spheres while underscoring women’s growing leadership in American modern dance and modern Jewish life.

Rebecca Rossen is assistant professor in the Department of Theatre and Dance at the University of Texas at Austin, and a faculty affiliate in Jewish Studies, American Studies, and Women’s and Gender Studies. She has published articles in TDR: The Drama Review, Theatre Journal, and Feminist Studies, and is the author of Dancing Jewish: Jewish Identity in American Modern and Postmodern Dance (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only theatre and dance articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Hasidic drag in American modern dance appeared first on OUPblog.