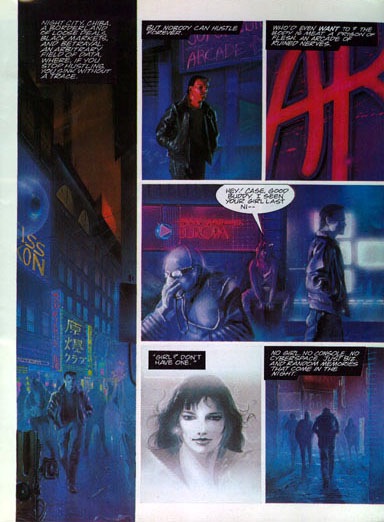

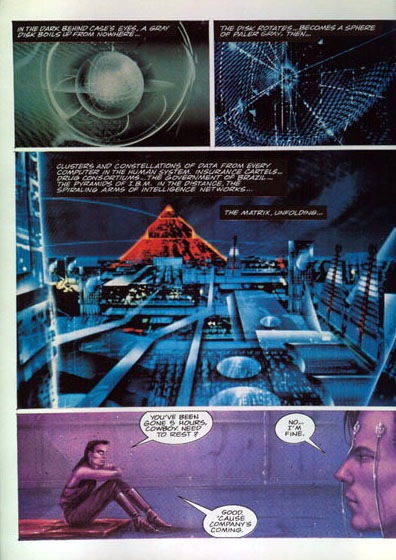

Considering that William Gibson’s Neuromancer is one of my favorite books of all times, you’d think I’d have remembered that there was a comics adaptation, but no. Epic Comics put out half of it in one 44-page comic, written by Tom DeHaven and illustrated by Bruce Jensen. DeHaven has a look back on his part in it on his website.

My difficulties with the project had to do with the script process that I was expected to follow: the famous (or infamous) “Marvel Method.” Epic Comics, which publishedNeuromancer as a glossy large-format trade-paperback, was a subsidiary of Marvel Comics, and Marvel “culture” at the time insisted that a writer initially draft a succinctsummary of the story, which the artist would use in breaking down and penciling all of the pages. That meant, instead of writing a detailed panel-by-panel script, I had to write something like: “Page 1, Case is walking around Chiba City at night. Page 2, Case talks to Ratz and Linda Lee in a bar. Page 3. Linda Lee tells Case that Wage intends to kill him. He leaves the bar and walks around recalling his days as a console cowboy.” Etcetera. After working up that sort of uninflected précis—which was probably no longer than a couple of pages—I sent it off to Bruce Jensen (whom I never met, by the way, but that’s not unusual—I’ve never met half the cartoonists I’ve worked with). Jensen then did the page and panel breakdowns as he saw fit, roughing out everything, very loosely, in pencil.

This led to problems. Oh the olden days of comics.

DeHaven is a respected novelist (It’s Superman, Freaks Amour) who has written a lot about comics (Funny Papers), as well as actual comics. There’s lots of stuff on his website if you dig around, including a serialization of his new story, King Touey. Worth poking around.

In my absence here’s Maximus Clarke — aka the guy I’m married to — on, and in conversation with, William Gibson, one of his favorite writers. Gibson reads from his new book, Zero History

, tomorrow, 9/23, at the Union Square Barnes & Noble, at 7 p.m.

William Gibson rose to prominence a quarter century ago with a unique hybrid of science fiction, noir, and grimy realism, set in an amoral, multicultural, commercialized, networked future. Gibson developed his distinctive vision (dubbed “cyberpunk” by others) in a series of short stories written in the late ’70s and early ’80s. I remember discovering his writing around that time in Omni magazine, and realizing, young as I was, that this guy was operating on a whole different level from the conventional SF authors I’d grown up reading.

Gibson’s first novel, Neuromancer (1984), won science fiction’s three most prestigious awards, but was soon acclaimed well beyond the confines of the genre. Neuromancer deviated sharply from traditional “space opera” in its subject matter, portraying the cutthroat struggles of global conglomerates, street gangs, and computer jockeys who hack into online systems brain-first. But it was Gibson’s virtuosic style that gained him literary respect.

As an introverted teen, he’d been an equally avid consumer of pulp sci-fi and the writings of William S. Burroughs and friends. As a writer, Gibson developed a blend of clipped, hard-boiled language and dense, sometimes overwhelming imagery. His work has often featured allusions to Asian, European and Caribbean cultures, street-level snapshots of decaying cityscapes, and fragments of consumer technology and broadcast media. Narratives tend to emerge gradually, from the perspectives of multiple protagonists.

Neuromancer and its two sequels were followed by The Difference Engine (an alternate-history tale of a computerized Victorian England, co-authored with Bruce Sterling), and a trilogy of novels revolving around a near-future version of San Francisco. But as the 21st century unfolded in ways that neither Gibson nor anyone else had quite foreseen, he turned his attention to writing about the present.

Pattern Recognition (2003), Spook Country (2007), and the recently released Zero History are, Gibson told me, “speculative novels of last Wednesday”: adventures in the stranger-than-fiction contemporary world, as seen through a science-fiction lens. Instead of making alien futures familiar, these stories show us the familiar present in an alien light. They remind us that our age of fetishized fashion, shadowy capital flows, digital art, devious marketing, and military contractors run amok is a deeply weird time to be alive.

MC: In your fiction, certain physical objects have extraordinary presence — they become more than just plot devices. The Cornell boxes in Count Zero, the

MC: In your fiction, certain physical objects have extraordinary presence — they become more than just plot devices. The Cornell boxes in Count Zero, the

MC: In your fiction, certain physical objects have extraordinary presence — they become more than just plot devices. The

MC: In your fiction, certain physical objects have extraordinary presence — they become more than just plot devices. The