The brain is a product of its complex and multi-million year history of solving the problems of survival for its host, you, in an ever-changing environment. Overall, your brain is fairly fast but not too efficient, which is probably why so many of us utilize stimulants such as coffee and nicotine to perform tasks more efficiently. Thus far, no one has been able to design a therapy that can make a person truly smarter.

The post A magical elixir for the mind appeared first on OUPblog.

By Sergio Della Sala

We are besieged by misinformation on all sides. When this misinformation masquerades as science, we call it pseudoscience. The scientific tradition has methods that offer a way to get accurate evidence and decrease the chance of misinformation persisting for long. The application of these rules marks the difference between science and pseudoscience. Perhaps more importantly, accepting these rules allows us to admit what we do not yet know, and avoids the pomposity too often associated with the notion of scientific authority.

We are easy prey for pseudoscience. We are natural believers, especially in things that we would like to be true. This belief may be fostered by trusting web surfing. We come to believe that our children can improve their scholastic performances by gulping up fishy pills or other improbable supplements. We would like to be more intelligent and show off our skills in solving puzzles, have better memory and absorb volumes of material effortlessly, and to flaunt our astuteness and acumen at parties. To reach these goals by long hours of swotting is a daunting prospect, so we jump at the idea of a quick fix and are prepared to pay for it.

Take the simplistic dichotomy between the two brain hemispheres that informs a series of training programmes. Such programmes are based on the popular assumption that our brains have a nerdy left hemisphere, which acts as a rigorous accountant, opposed to a creative, hippie half, the right hemisphere (which usually needs to be awakened).

Newsmakers fuel belief in tall tales by running uncritical stories advertising outlandish methods and ignoring their obvious flaws. So we can blame the journalists: easy target. However, when we scientists engage with the public, do we really do any better? We are now all desperate to engage the public; our institutions push us to branch out and reach out, and we get brownie points if we do so. This activity too often translates into a scientist going to the media saying “I have nothing to say, and I want to say it on TV.” It sometimes seems that it is the engagement itself that is valued, independently of what we actually say.

There is nothing wrong if you are not interested in science, but if you are then nowadays there are plenty of opportunities to indulge your curiosity. Science festivals are springing up in every city. However, the idea that simply discussing science publicly can counter misinformation is naïve. I posit that too often than it would be advisable, scientists themselves promulgate pseudoscientific thinking, so even science festivals may be counterproductive. Engaging with the public should push scientists to show the evidence and praise scientific methods. We should not abuse the position to dominate by authority.

The Royal Society‘s motto ‘Nullius in verba’ is Latin for, roughly, ‘take nobody’s word for it’. We scientists should remember this motto, not only in our labs, but also when disseminating our ideas. Yet we seem to know no better. Kary Mullis, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, asserted in his autobiography his belief in astrology. But he is a Capricorn. I’m a Libran, and Librans do not believe in astrology.

Sergio Della Sala is Professor of Human Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of Edinburgh, and co-editor of Neuroscience in Education: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Cod liver oil capsules. Photo by Adrian Wold. CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Pseudoscience surplus appeared first on OUPblog.

By Dean Falk, Fred Lepore, and Adrianne Noe

Imagine that you return from work to find that a thief has broken into your home. The police arrive and ask if they may dust for finger and palm prints. Which would you do? (A) Refuse permission because palm reading is an antiquated pseudoscience or (B) give permission because forensic dermatoglyphics is sometimes useful for identifying culprits. A similar question may be asked about the photographs of the external surface of Albert Einstein’s brain that recently emerged after being lost to science for over half a century. If asked whether details of Einstein’s cerebral cortex should be identified and interpreted from the photographs, which would you answer? (A) No, because to conduct such a study would engage in the 19th century pseudoscience of phrenology or (B) Yes, because the investigation could produce interesting observations about the cerebral cortex of one of the world’s greatest geniuses and, in light of recent functional neuroimaging studies, might also suggest potentially testable hypotheses regarding Einstein’s brain and those of normal individuals. Lest you think this is a straw man (or Aunt Sally) exercise, more than one pundit has recently invoked the phrenology argument against studying Einstein’s brain. For example, one blogger opines, “I hope no one cares about Einstein’s brain. By this I mean his brain anatomy.” The three of us who were privileged to describe the treasure-trove of recently emerged photographs opted for B.

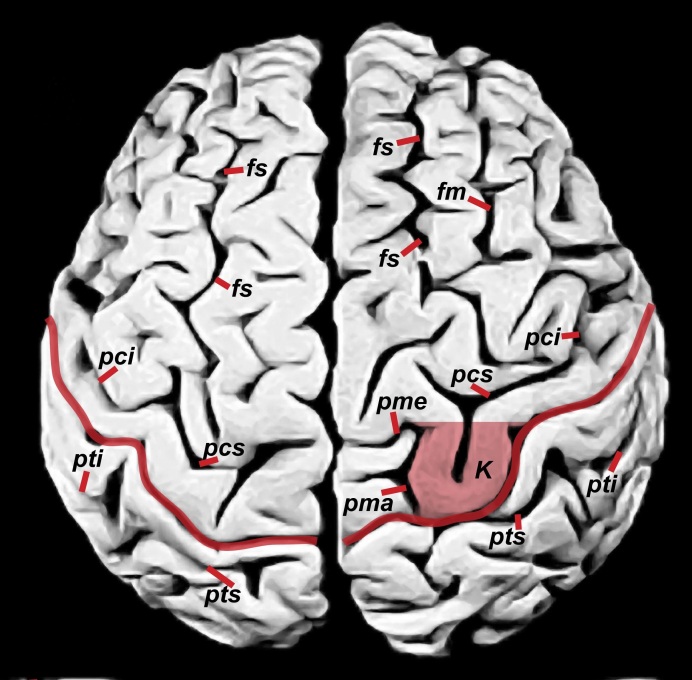

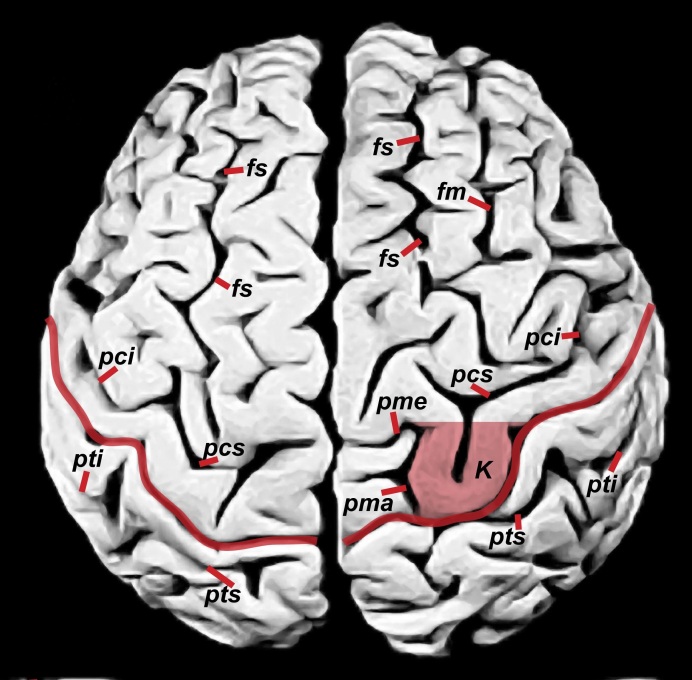

We did so because various data support studying the variation and functional correlates of folds (gyri) on the surface of the human brain and the grooves (sulci) that separate them. For example, David Van Essen hypothesizes that tensions along the connections between cells that course beneath the surface of the brain explains typical patterns of convolutions on its surface. Disruptions in the development of these connections in humans may result in abnormal convolutions that are associated with neurological problems such as autism and schizophrenia. Representations in sensory and motor regions of the cerebral cortex may change later in life as shown by imaging studies of Braille readers, upper limb amputees, and trained musicians, and sometimes these adaptations are correlated with superficial neuroanatomical features such as an enlargement in the right precentral gyrus (called the Omega Sign because of its shape) associated with movement of the left hand in expert string-players. Indeed, Einstein’s right hemisphere has an Omega Sign (labeled K in the following photograph, for knob), which is consistent with the fact that he was a right-handed string-player who took violin lessons between the ages of 6 and 14 years. The aforementioned blogger supports his opposition to studying Einstein’s cerebral cortex with the observation that “assuming causality with correlation” is “a cardinal sin of science”. However, this old saw does not mean that correlated features are necessarily causally unrelated. The functional imaging literature on the cerebral cortices of musicians and controls suggests that Einstein’s Omega Sign and his history as a violinist were probably not an unrelated coincidence.

Superior view of Einstein’s brain, with frontal lobes at the top. The shaded convolution labeled K is the Omega Sign (or knob), which is associated with enlargement of primary motor cortex for the left hand in right-handed experienced string-players.

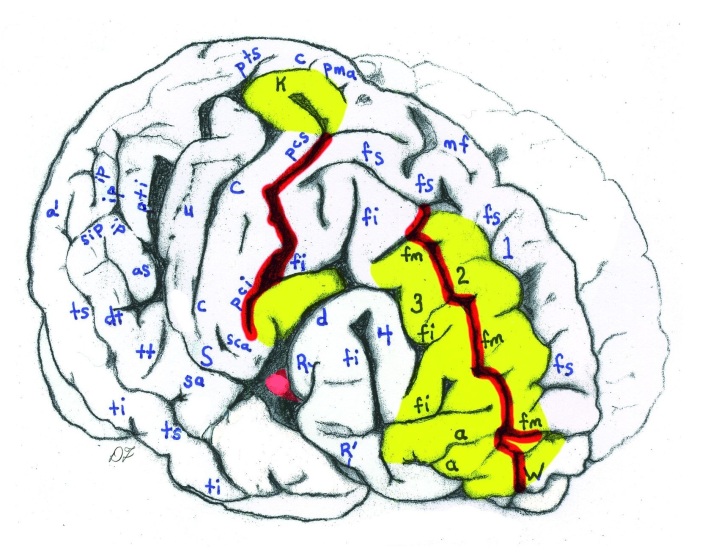

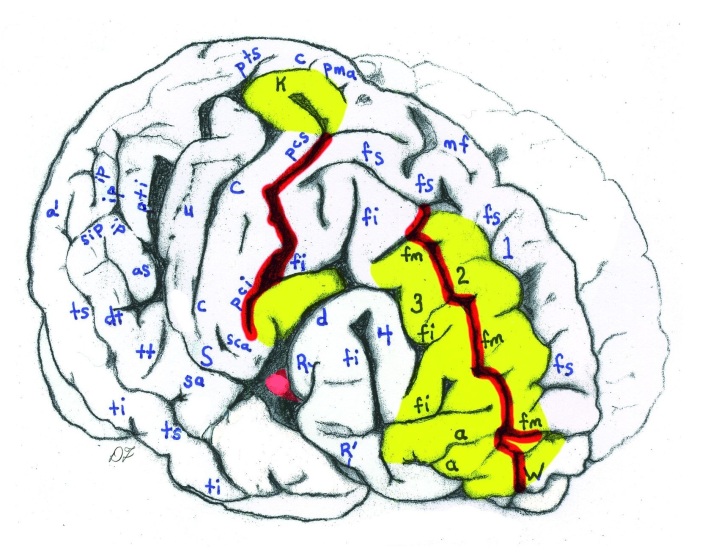

The investigation of previously unpublished photographs of Einstein’s brain reveals numerous unusual cortical features which suggest hypotheses that others may wish to explore in the histological slides of Einstein’s brain that surfaced along with the photographs. For example, Einstein’s brain has an unusually long midfrontal sulcus that divides the middle frontal region into two distinct gyri (labeled 2 & 3 in the following image), which causes his right frontal lobe to have four rather than the typical three gyri. An extra frontal gyrus is rare, but not unheard of. Einstein’s frontal lobe morphology is interesting because the human frontal polar region expanded differentially during hominin evolution, is involved in higher cognitive functions (including thought experiments), and is associated with complex wiring underneath its surface. These data suggest that the connectivity associated with Einstein’s prefrontal cortex may have been relatively complex, which could potentially be explored by investigating histological slides that were prepared from his brain after it was dissected.

Tracing from photograph of the right side of Einstein’s brain taken with the front of the brain rotated toward viewer. Unusual sulcal patterns are indicated in red; rare gyri are highlighted in yellow.

The microstructural organization in the parts of the cerebral cortex that are involved heavily in speech (Broca’s area and its homologue) were shown to be unique in their patterns of connectivity and lateralization in the genius Emil Krebs, who spoke more than 60 languages. That study, however, did not include information about the gross external neuroanatomy in the relevant regions. Functional neuroimaging technology is making it possible to explore the functional relationships between variations in external cortical morphology, subsurface microstructure including neuronal connectivity, and cognitive abilities. In other words, scientists should now be able to analyze form and function cohesively from the external surface of the cerebral cortex into the depths of the brain. Pseudoscience this is not.

Dr Dean Falk is the Hale G. Smith Professor of Anthropology at Florida State University and a Senior Scholar at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Dr Fred Lepore is Professor of Neurology and Ophthalmology at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in Piscataway, New Jersey. Dr Adrianne Noe is Director of the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland. You can read their paper, ‘The cerebral cortex of Albert Einstein: a description and preliminary analysis of unpublished photographs’ in full and for free. It appears in the journal Brain.

Brain provides researchers and clinicians with the finest original contributions in neurology. Leading studies in neurological science are balanced with practical clinical articles. Its citation rating is one of the highest for neurology journals, and it consistently publishes papers that become classics in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Both images are authors’ own. Do not reproduce without prior permission from the authors.

The post Examining photographs of Einstein’s brain is not phrenology! appeared first on OUPblog.