As I write nonfiction books, I carefully consider sentence length and punctuation. Every sentence is crafted in a way that will support the pacing of my (true) story. Does sentence structure and punctuation affect the pacing of the story? Absolutely! How you write the text makes all the difference.

As an example, let’s consider the opening scene from my book,

Fourth Down and Inches:

Concussions and Football’s Make-or-Break Moment

I could have begun this book in countless ways. I chose to begin the book with a young man named Von Gammon because I believe it sets the scene for the whole book. I wanted to pull the reader in by giving them a glimpse into Von’s life. Once I decided to open the book with this young man, there were countless ways I could have written the scene.

Consider the following examples and choose which is more compelling:

EXAMPLE 1

Von Gammon lay down on the grass. He told his brother to stand on his hands. Von was strong and could prove it. He could lift his brother who was six feet six inches tall off the ground. Von was strong and skilled.

OR…

EXAMPLE 2

Von Gammon lay down on the grass and told his brother to stand on his hands. Von was strong, and he could prove it. Then he lifted his brother—all six feet and six inches of him—clear off the ground. And Von wasn’t just strong; he was skilled.

The second example is what appears in the published book. The first example communicates the same information, but doesn’t pull the reader into the story. The difference is in the sentence structure and punctuation.

Just a few sentences later, I write about the moment things changed for Von. Which of the following is more interesting?

EXAMPLE 1

When Von was a sophomore, he played in a football game that took place on October 30. He was on the University of George team and they were playing the University of Virginia. Von’s team was behind by seven points. The other team had control of the ball. Von was a defensive lineman. When the ball was snapped and the play began, the linemen hit each other. Von laid on the field after all the other players walked away.

OR…

EXAMPLE 2

On October 30 of Von’s sophomore year, the Georgia Bulldogs were battling the University of Virginia. They trailed by seven points, and Virginia had the ball. Von took his place on the defensive line. The center snapped the ball. A mass of offensive linemen lurched toward Von, and he met them with equal force.

The play ended in a stack of tangled bodies.

One by one, the Virginia players got up and walked away. Von didn’t.

The second example appears in the published book. Again it isn’t the information that is different; it is how the information is presented that is different.

Why did I begin

Fourth Down and Inches:

Concussions and Football's Make-or-Break Moment

with Von Gammon?

Because Von sustained a concussion and died a few hours later. His death caused many to wonder if football was too dangerous.

The year was 1897.

Carla Killough McClafferty

BOOK GIVEAWAY!

Win an autographed copy Baby Says “Moo!” by JoAnn Early Macken. For more details on the book and enter the book giveaway, see her blog entry on June 12, 2015. The giveaway runs through June 22. The winner will be announced on June 26.

|

My kitty, Comma.

|

“What is one man’s colon is another man’s comma.” ~

Mark TwainAs a writing teacher, and a working writer, I found the greatest challenge is learning the fine art of punctuation. The secret, I discovered, is writing for the reader's eye.

Understanding how the reader approaches text offers you key insight into how to write with clarity and grace.

Readers approach the text by moving left to right. Readers interpret information by this forward projection. Readers expect subject-verb-object structures in sentences. They tend to focus on the verb that resolves the sentence's syntax, and in so doing, tend to resist information until after the verb is identified. This is why concrete subjects and action-oriented verbs carry the weight of the sentence. If the subject is vague or nonexistent, or the verb is passive, the sentence often falls apart.

Because readers project forward, they intuitively search for the subject, skimming over qualifying clauses or phrases that precede the subject. This becomes important in longer sentences, when the subject does not debut until mid-way or beyond. This is why subjects placed as close to the opening of the sentence as possible make for stronger sentences.

Active voice maintains this forward process. It originates with the grammatical subject, flows through the verb, and results in an outcome. Some research suggests that readers understand and remember information more readily when structure corresponds to this cause-effect sequence. Passive structure forces this action in reverse: a subject is either implied or supplied in a subordinate phrase, and the outcome becomes the grammatical subject.

The rhythm of a narrative is found in its punctuation. As sentences crash and fall “like the waves of the sea,” punctuation becomes the music of the language, says Noah Lukeman, in one of my favorite reads,

A Dash of Style (2006).

Periods are the stop signs, says Lukeman, and hold the most power in the punctuation universe.

|

| morguefile.com |

All other marks – the comma, the dash, the colon and semi-colon, and so on – serve only to modify what lies between the periods. Sometimes a usurper, like the exclamation point or the question mark, intervenes, but its control is temporary. Imagine a book without periods, or a book that has periods after every word, and you begin to understand its supreme power.

A well-placed period, especially in battle with one of its usurpers, helps pacing and adds emphasis. It speeds the narrative up in an action-sequence, heightening the drama. For example, can you hear the drum beat in this passage from my book,

Girls of Gettysburg (Holiday House, 2014)?

Bayonets glistening in the hot sun, the wall of men stepped off the rise in perfect order. The cannoneers cheered as the soldiers moved through the artillery line, into the open fields.

The line had advanced less than two hundred yards when the Federals sent shell after shall howling into their midst.

Boom! Boom! Boom!

The shells exploded, leaving holes where the earth had been. Shells pummeled the marching men. As one man fell in the front of the line, another stepped up to take his place. Smoke billowed into a curtain of white, thick and heavy as fog, stalking them across the field.

Still they marched on. They held their fire, waiting for the order.

Boom! A riderless horse, wide-eyed and bloodied, emerged from the cloud of smoke. It screamed in panic as another shell exploded.

Boom! All around lay the dead and dying. There seemed more dead than living now. Men fell legless, headless, armless, black with burns and red with blood.

Boom! They very earth shook with the terrible hellfire.

Still they marched on.

Long sentences can be very effective to heighten emotional drama even as it slows the action down. In another example from

Girls of Gettysburg: “

Dawn broke still as pond water, and the army was already on the march, moving east along the Pike. As the bloody sun broke free of the horizon, the mist rose, too. The air heated steadily, another hellfire day.”

But, as the cliché reminds us, there can be too much of a good thing (except chocolate, of course). A string of short sentences can become a choppy ride.

Like riding in a Model T Ford. Stuck in the wrong gear. Chug! Chug! Chug! Going over a rutted road. It bounces. And bounces. And bounces. My head hurts. Ouch! Ouch! Ouch! Stop. This. Car. And. Let. Me. Out. And no one wants to read a sentence that never ends, one that goes on and on and on and on, in some stream-of-consciousness rambling of fanciful swooping and looping and drooping that serves no purpose other than to satisfy the writer’s ego.If the period is the stop sign, then the comma is the speed bump, says Lukeman. It controls the ebb and flow of the sentence’s rhythm. A comma connects and divides. In fact, as Lukeman warns, it’s downright schizophrenic. It divides the sentences into parts, clarifying its meaning, or in some cases, changing its meaning. Consider this favorite Facebook meme:

A woman, without her man, is nothing. But, with a wave of the magic punctuation wand, it changes to this: A woman: without her, man is nothing.A comma connects smaller ideas to create a more powerful idea:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.Everyone has heard the saying, placing a comma is like taking a breath in a sentence. But a sentence with too many commas sends the reader into hyperventilation. And one with not enough commas forces the reader to hold her breath unto she turns

blue. So, where do you place your comma?

There are a thousand handbooks on punctuation, each offering a thousand rules on where and when to place a comma, and each rule has a thousand exceptions.

Perhaps the better question is: what is your purpose in using the comma? As a stylistic devise, I offer that it’s one of the most emotive punctuation marks because it mimics the character’s state of mind. For example, from my

Girls of Gettysburg, you know this poor character is frightened: “

Weezy sang, quiet as a cricket’s whisper. But in the tiny room, in the dark, it seemed loud enough.”

Somewhere between the period and the comma is the semi-colon. This is the mediator, says Lukeman, and “

a bridge between the two worlds.” With a style all its own, the semi-colon connects two thematically-related ideas while maintaining the independence of both.

|

| morguefile.com |

It can be used to smooth out the choppy ride found in a string of short sentences, or give a breath of air in a long-winded sentence.

However, the semi-colon doesn’t always play well with others. It competes for attention with the comma. Because a semi-colon slows the action down, the effect of a comma and, most especially the period, is minimized.

And then there are colons. Colons are just plain bossy. They don't like to share. They especially don’t like semi-colons, despite the similar names. With a flair for the dramatic, colons are the master magicians: they reveal. (<

See what I did there?) Colons hold the audience in suspense, says Lukeman. Then, at the right moment, the writer pulls the curtain back to reveal some fundamental truth of the narrative. Remember the Facebook meme example?

A woman: without her, man is nothing.

But too often misunderstood and underappreciated, the colon tends to be reduced to mundane tasks, like signaling lists and offering summaries.

Then, of course, there are the dashes, ellipses, slashes and myriad of other punctuation marks. Alas, I’ve run out of space. In the end, as Noah Lukeman says, punctuation is organic, a complex universe subject to the writer’s purpose and personal tastes. What works in one narrative doesn’t work in every narrative. And for every rule, there is an exception. At its core, however, punctuation is a journey of self-awareness and reveals as much about the writer as it does about the writing.

For more information, you might find these useful:

Boyle, Toni and K.D. Sullivan. The Gremlins of Grammar. NY: McGraw-Hill, 2006.

Lukeman, Noah. A Dash of Style. NY: WW Norton, 2006.

Bobbi Miller “Punctuation in skilled hands is a remarkably subtle system of signals, signs, symbols and winks that keep readers on the smoothest road. Too subtle, perhaps: Has any critic or reviewer ever praised an author for being a master of punctuation, a virtuoso of commas? Has anyone every won a Pulitzer, much less a Nobel, for elegant distinctions between dash and colon, semi-colon and comma? ~ Rene J. Cappon, Associated Press Guide to Punctuation

A child learns early on to recognize tone of voice. The mother's soft, sweet coo means she is happy with him. The low growl utilizing his middle name means he pushed the boundaries a tad too far, but what does tone have to do with fiction?

Tone is the emotional atmosphere the writer establishes and maintains throughout the entire novel based on how the author, through the point of view character, feels about the information she relates.

You may not have thought about how you actually feel about your story. Take a moment to consider. Are you writing about ghosts with a wink and a nudge or are you aiming for chill bumps? Is the story serious and bittersweet or a satirical exposé?

1. Tone can be formal or informal, light or dark, grave or comic, impersonal or personal, subdued or passionate, reasonable or irrational, plain or ornate.

The narrator can be cynical, sarcastic, sweet, or funny. A satirical and caustic tone plays well in a dark Comedy. It won't play well in a cozy Mystery.

2. Tone should suit genre.

Are you writing a shallow Chick Lit comedy or a dark and mysterious Gothic novel? If you write a mixed genre, the tone should match the genre that takes precedence over the other.

If you are writing a funny romance, you have to decide if you want your reader to belly laugh her way through it or have a few moments that make her belly laugh while worrying about the outcome of the relationship. Some Romance fans love a frothy, light tone. Others prefer the melodramatic tone of Historical Romance. Yet another prefers a heart-wrenching Literary love story.

Some paranormal stories are eerie and set an ominous tone. Light Horror feels almost comic to the reader. Readers who prefer ominous, creepy paranormal might not enjoy the comical version.

3. Tone is demonstrated by word choice and the way you reveal the details.

It informs the narrator's attitude toward the characters and the situation through his interior narration, his actions, and his dialogue. If he does not take the characters or situation seriously, the reader won't either. Word choice, syntax, imagery, sensory cues, level of detail, depth of information, and metaphors reveal tone.

4. Tone is not the same as voice.

Stephen King writes horror. His voice is distinct. At times he employs quirky, adolescent boy humor (his voice), but his aim is to chill you and his quips impart comic relief in a sinister story world. Being heavy-handed with the humor can ruin a good horror story, even turn it into parody.

5. Tone is not the same as mood.

Tone is how the author/narrator approaches the scene. Mood is the atmosphere you set for the scene. If you are writing a mystery, a scene can be brooding and dark leading up to the sleuth finding the body. The mood can lighten as the detectives indulge in a moment of gallows humor. Tone defines your overall mystery as wisecracking noir or cozy British as they solve the crime.

6. Tone is not the same as style.

Style reflects the author or narrator's voice. It is also revealed through sentence structure, use of literary devices, rhythm, jargon, slang, and accents. Style is revealed through dialogue. Style showcases the background and education of the characters. It expresses the cast's belief system, opinions, likes, and dislikes. It is controlled by what the characters say and how they say it. Tone is revealed by the narrator's perceptions, what he chooses to explore, and what he chooses to hide.

Stay tuned for examples of tone next week.

For these and other tips on revision, pick up a copy of:

.

.

Don’t Dangle Your Participle

by Vanita Oelschlager & Mike DeSantis, illustrator

Vanita Books 5/01/2014

978-1-938164-02-6

Age 4 to 8 24 pages

.

“Words and pictures show children what a dangling participle is all about. Young readers are shown an incorrect sentence that has in it a dangling participle. They are then taught how to make the sentence read correctly. It is done in a cute and humorous way. The dangling participle loses its way and the children learn how to help it find its way back to the correct spot in the sentence. This is followed by some comical examples of sentences with dangling participles and their funny illustrations, followed by an illustration of the corrected sentence. Young readers will have fun recognizing this problem in sentence construction and learning how to fix it.”

Opening

“What on earth is a participle and how does it dangle? Okay. Okay. Let’s start from the beginning.”

Review

In Don’t Dangle Your Participle Vanita explains what a dangling participle is and explains how to fix the sentence so that the participle no longer dangles and mangles the sentence’s meaning. The participle comes before the noun to clarify it, but Vanita shows how easy it is for the modifier to get lost, ending up in the wrong place in the sentence. If you still don’t get it from that explanation, well, this is because explanations are easier to understand when Vanita adds in pictures to make her point.

And it works!

I know this because dangling participles (and dangling modifiers, but that is another story) have always confused me, BUT honest, after reading Don’t Dangle Your Participle, I understand what a dangling participle is and how to correct the sentence and send the raskly participle on its way to bother someone else’s sentence. Don’t Dangle Your Participle belongs in every school library and language arts classrooms. Using humorous illustrations, Vanita shows how the participle, when left to dangle, changes the meaning of the sentences often with disastrous consequences. Try this one.

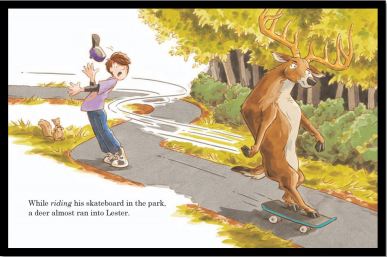

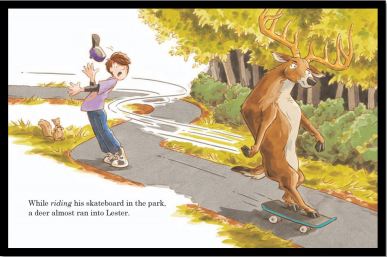

- While riding his skateboard in the park, a deer almost ran into Lester.

What this sentence is saying is this: When the deer rode his skateboard in the park, it almost ran into Lester. This is not what the sentence was supposed to mean. The dangling Participle—riding—changed the meaning of the sentence to something unintended and, as shown by the illustration, often something unintentionally funny. Vanita clearly shows kids how to fix these sentences.

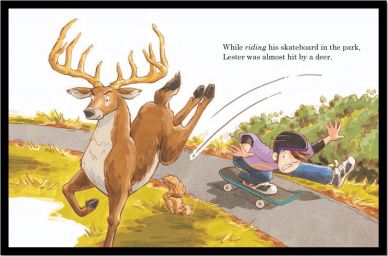

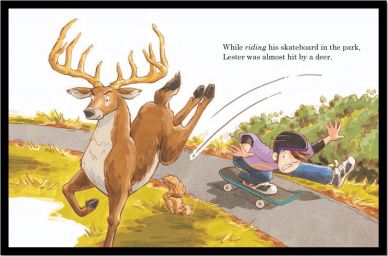

Did you get the correct sentence? Maybe another illustration will help.

Correct: While riding his skateboard in the park, Lester was almost hit by a deer.

Vanita has a canny way of helping kids understand English and its many rules. She effectively uses humor, which can help a child remember a concept. The more senses involved in learning, the better the material will be remembered. Vanita easily explains a subject, breaking it down so that kids can get the concept quickly. Don’t Dangle Your Participle may be her best language arts book yet.

Don’t Dangle Your Participle can help teachers explain sentence structure in general and the dangling participle. Many of Vanita’s books make great adjunct texts, especially in a homeschooling situation. For those kids that like to learn, Vanita Books make learning loads of fun. Don’t Dangle Your Participle helps the teacher and student, and charitable organizations—all net profits go to select charities. Try one more. Are you ready?

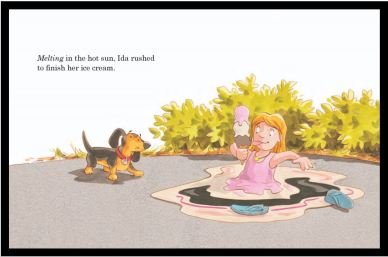

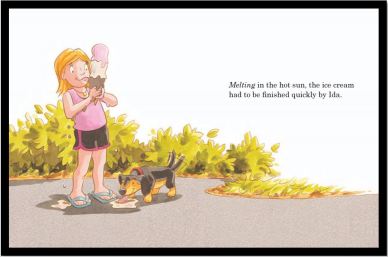

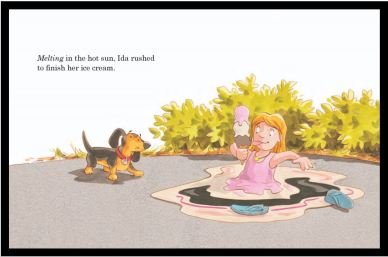

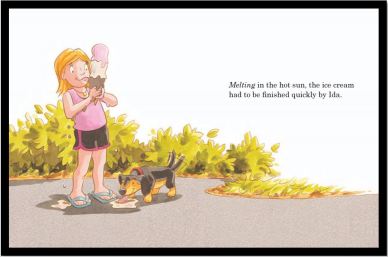

- Melting in the hot sun, Ida rushed to finish her ice cream.

This sentence says, As Ida was melting, she rushed to finish her ice cream. The dangling participle—melting—changed the meaning of this sentence. The writer is trying to say, the ice cream was melting, but darn it, he dangled the participle!

I bet you figured out the correct sentence. Just in case, here it is with a visual aide.

Correct: Melting in the hot sun, the ice cream had to be finished quickly

English is a difficult language. The rules are numerous and onerous. Kids need all the help they can get in understanding how to write English. Don’t Dangle Your Participle can be that help and should be available to every school child by way of the classroom and the library. Vanita explains the participle—a verb that acts like an adjective—and what happens when the participle no longer comes before the proper noun—it dangles. Her use of fun and funny illustrations help drive home her explanations. If I can finally understand these dangerous dangling participles, kids will be able to and probably faster. Use Don’t Dangle Your Participle can be used at home and at school to increase your child’s ability to write English properly. A skill that will help children their entire life.

.

Learn more about Don’t Dangle Your Participle HERE.

Buy Don’t Dangle Your Participle at Amazon—B&N—Vanita Books—your local bookstore.

.

Meet the author, Vanita Oelschlager at her website: http://vanitabooks.com/MeetVanita.html

Meet the illustrator, Mike DeSantis at his website: http://www.mikedesantis.com/picblog/

Find more wonderful Vanita Books at the publisher’s website: http://vanitabooks.com/index.html

.

DON’T DANGLE YOUR PARTICIPLE. Text copyright © 2014 by Vanita Oelschlager. Illustrations copyright © 014 by Mike DeSantis. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Vanita Books, Akron, OH.

. ALSO BY VANITA BOOKS

The Pullman Porter

Knees

Farfalla

Ariel Bradley

Magic Words

.

.

Reviews: The Pullmn Porter–Knees–Farfalla–Ariel Bradley–Magic Words

Filed under:

6 Stars TOP BOOK,

Children's Books,

Favorites,

Library Donated Books,

NonFiction,

Picture Book,

Top 10 of 2014 Tagged:

children's book reviews,

dangling participles,

English language,

language arts for kids,

Mike DeSantis,

sentence structure,

vanita books,

Vanita Oelschlager

One of my editing instructors at the University of Chicago, Graham School, recommended How to Write a Sentence and How to Read One by Stanley Fish. I've scratched the surface of it and it already has started me thinking about our interactions with sentences.

Lately I've become conscious of my reading style. When I'm reading for pleasure/escape, I often read for a couple pages and realize my mind has strayed from the piece. If I feel like I've gotten the overall sense of the piece, I'll re-focus and keep reading. (Does this ever happen to you?) If I'm able to re-engage, then I generally can pick up the overall meaning--the forest--of the piece. (I tried to find another analogy, but the color of the fall leaves have been captivating!)

|

| Forest, trees or leaves | PHOTO: P. Humphrey |

If I re-engage in a piece and am swept away, I may return to what I missed. Over the weekend, while reading a book by one of my favorite novelists, I found myself reading more deliberately and fighting the urge to rush through it because it was so good.

My husband, who is not a writer or editor, practices the opposite to my reading habits. With

each piece of writing, he feels he must truly engage in the reading. It seems that he luxuriates in the words he is reading. He is an amazing reader to have because he takes such care. He looks at each tree in the forest and sometimes I suspect he is looking at every leaf.

When I edit, I travel all over the forest, staring at trees and leaves. I do manage to slow down my reading and study the writing. I become more professorial, pulling out a magnifying glass (or reading glasses) and wading in, as if on an expedition.

At the end of the day, it's always a nice feeling to have ventured into the forest and spend some time with the trees.

How about you and your forest adventures? Are you a forest or tree type--or do you venture in and stare at the leaves?

Elizabeth King Humphrey is a freelance writer and editor. After staring at trees, she plans to finish How to Write a Sentence and How to Read One

.

Great t!)jrt

I do try to stay with it and read what's been offered. If I realize I've "fuzzed out" and skipped over, then I go back and re-read. Sometimes clues are hidden in the most innocuous places,and I don't want to miss them!