About half a century ago, an MIT professor set up a summer project for students to write a computer programme that can “see” or interpret objects in photographs. Why not! After all, seeing must be some smart manipulation of image data that can be implemented in an algorithm, and so should be a good practice for smart students. Decades passed, we still have not fully reached the aim of that summer student project, and a worldwide computer vision community has been born.

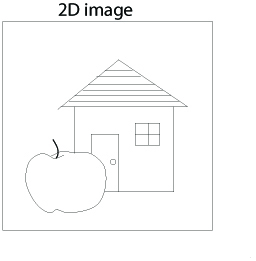

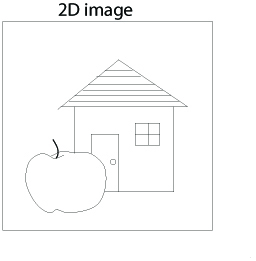

We think of being “smart” as including the intellectual ability to do advanced mathematics, complex computer programming, and similar feats. It was shocking to realise that this is often insufficient for recognising objects such as those in the following image.

Image credit: Fig 5.51 from Li Zhaoping,

Understanding Vision: Theory Models, and Data

Can you devise a computer code to “see” the apple from the black-and-white pixel values? A pre-school child could of course see the apple easily with her brain (using her eyes as cameras), despite lacking advanced maths or programming skills. It turns out that one of the most difficult issues is a chicken-and-egg problem: to see the apple it helps to first pick out the image pixels for this apple, and to pick out these pixels it helps to see the apple first.

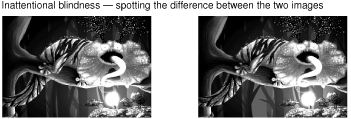

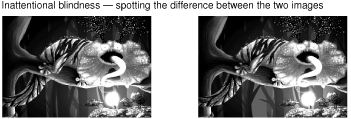

A more recent shocking discovery about vision in our brain is that we are blind to almost everything in front of us. “What? I see things crystal-clearly in front of my eyes!” you may protest. However, can you quickly tell the difference between the following two images?

Image credit: Alyssa Dayan, 2013 Fig. 1.6 from Li Zhaoping

Understanding Vision: Theory Models, and Data. Used with permission

It takes most people more than several seconds to see the (big) difference – but why so long? Our brain gives us the impression that we “have seen everything clearly”, and this impression is consistent with our ignorance of what we do not see. This makes us blind to our own blindness! How we survive in our world given our near-blindness is a long, and as yet incomplete, story, with a cast including powerful mechanisms of attention.

Being “smart” also includes the ability to use our conscious brain to reason and make logical deductions, using familiar rules and past experience. But what if most brain mechanisms for vision are subconscious and do not follow the rules or conform to the experience known to our conscious parts of the brain? Indeed, in humans, most of the brain areas responsible for visual processing are among the furthest from the frontal brain areas most responsible for our conscious thoughts and reasoning. No wonder the two examples above are so counter-intuitive! This explains why the most obvious near-blindness was discovered only a decade ago despite centuries of scientific investigation of vision.

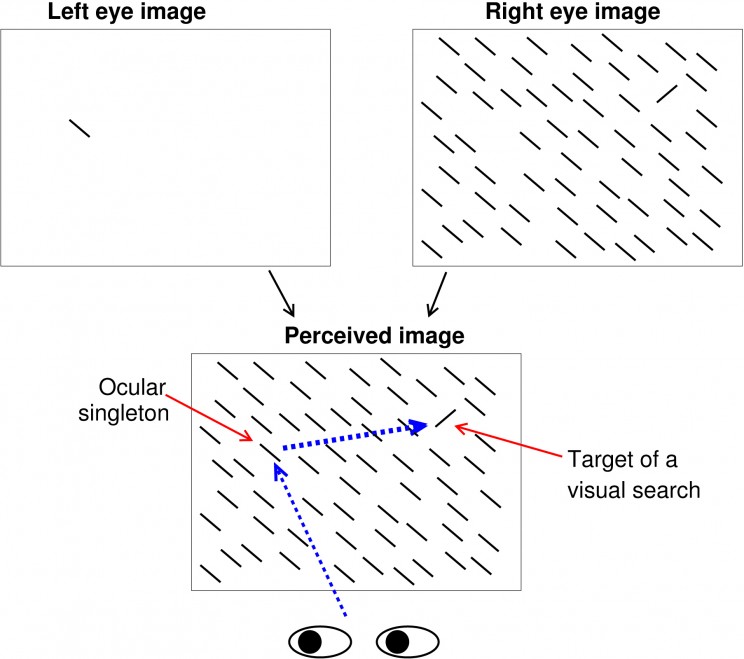

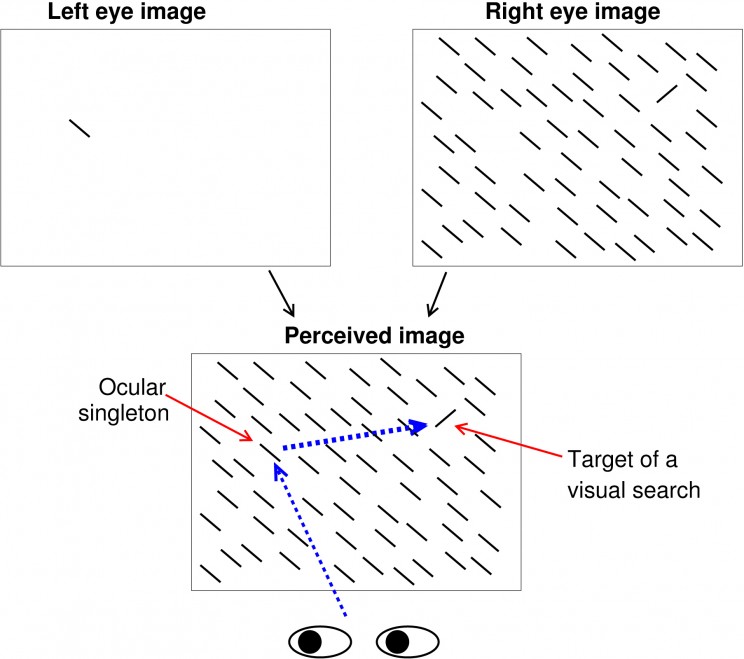

Another counter-intuitive finding, discovered only six years ago, is that our attention or gaze can be attracted by something we are blind to. In our experience, only objects that appear highly distinctive from their surroundings attract our gaze automatically. For example, a lone-red flower in a field of green leaves does so, except if we are colour-blind. Our impression that gaze capture occurs only to highly distinctive features turns out to be wrong. In the following figure, a viewer perceives an image which is a superposition of two images, one shown to each of the two eyes using the equivalent of spectacles for watching 3D movies.

Image credit: Fig 5.9 from Li Zhaoping,

Understanding Vision: Theory Models, and Data

To the viewer, it is as if the perceived image (containing only the bars but not the arrows) is shown simultaneously to both eyes. The uniquely tilted bar appears most distinctive from the background. In contrast, the ocular singleton appears identical to all the other background bars, i.e. we are blind to its distinctiveness. Nevertheless, the ocular singleton often attracts attention more strongly than the orientation singleton (so that the first gaze shift is more frequently directed to the ocular rather than the orientation singleton) even when the viewer is told to find the latter as soon as possible and ignore all distractions. This is as if this ocular singleton is uniquely coloured and distracting like the lone-red flower in a green field, except that we are “colour-blind” to it. Many vision scientists find this hard to believe without experiencing it themselves.

Are these counter-intuitive visual phenomena too alien to our “smart”, intuitive, and conscious brain to comprehend? In studying vision, are we like Earthlings trying to comprehend Martians? Landing on Mars rather than glimpsing it from afar can help the Earthlings. However, are the conscious parts of our brain too “smart” and too partial to “dumb” down suitably to the less conscious parts of our brain? Are we ill-equipped to understand vision because we are such “smart” visual animals possessing too many conscious pre-conceptions about vision? (At least we will be impartial in studying, say, electric sensing in electric fish.) Being aware of our difficulties is the first step to overcoming them – then we can truly be smart rather than smarting at our incompetence.

Headline image credit: Beautiful woman eye with long eyelashes. © RyanKing999 via iStockphoto.

The post Are we too “smart” to understand how we see? appeared first on OUPblog.

By Laura Kelley and Jennifer Kelley

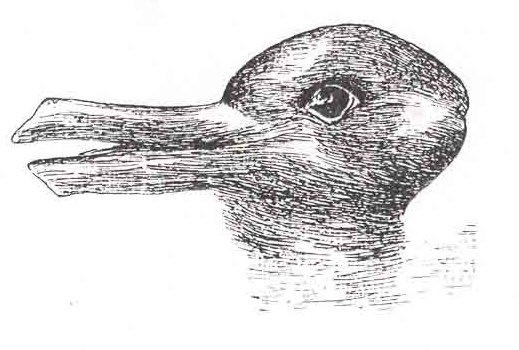

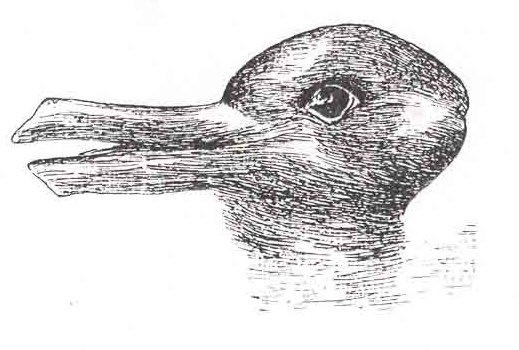

Visual illusions, such as the rabbit-duck (shown below) and café wall are fascinating because they remind us of the discrepancy between perception and reality. But our knowledge of such illusions has been largely limited to studying humans.

That is now changing. There is mounting evidence that other animals can fall prey to the same illusions. Understanding whether these illusions arise in different brains could help us understand how evolution shapes visual perception.

For neuroscientists and psychologists, illusions not only reveal how visual scenes are interpreted and mentally reconstructed, they also highlight constraints in our perception. They can take hundreds of different forms and can affect our perception of size, motion, colour, brightness, 3D form and much more.

Artists, architects and designers have used illusions for centuries to distort our perception. Some of the most common types of illusory percepts are those that affect the impression of size, length, or distance. For example, Ancient Greek architects designed columns for buildings so that they tapered and narrowed towards the top, creating the impression of a taller building when viewed from the ground. This type of illusion is called forced perspective, commonly used in ornamental gardens and stage design to make scenes appear larger or smaller.

As visual processing needs to be both rapid and generally accurate, the brain constantly uses shortcuts and makes assumptions about the world that can, in some cases, be misleading. For example, the brain uses assumptions and the visual information surrounding an object (such as light level and presence of shadows) to adjust the perception of colour accordingly.

Known as colour constancy, this perceptual process can be illustrated by the illusion of the coloured tiles. Both squares with asterisks are of the same colour, but the square on top of the cube in direct light appears brown whereas the square on the side in shadow appears orange, because the brain adjusts colour perception based on light conditions.

These illusions are the result of visual processes shaped by evolution. Using that process may have been once beneficial (or still is), but it also allows our brains to be tricked. If it happens to humans, then it might happen to other animals too. And, if animals are tricked by the same illusions, then perhaps revealing why a different evolutionary path leads to the same visual process might help us understand why evolution favours this development.

The idea that animal colouration might appear illusory was raised more than 100 years ago by American artist and naturalist Abbott Thayer and his son Gerald. Thayer was aware of the “optical tricks” used by artists and he argued that animal colouration could similarly create special effects, allowing animals with gaudy colouration to apparently become invisible.

In a recent review of animal illusions (and other sensory forms of manipulation), we found evidence in support of Thayer’s original ideas. Although the evidence is only recently emerging, it seems, like humans, animals can perceive and create a range of visual illusions.

Animals use visual signals (such as their colour patterns) for many purposes, including finding a mate and avoiding being eaten. Illusions can play a role in many of these scenarios.

Great bowerbirds could be the ultimate illusory artists. For example, their males construct forced perspective illusions to make them more attractive to mates. Similar to Greek architects, this illusion may affect the female’s perception of size.

Animals may also change their perceived size by changing their social surroundings. Female fiddler crabs prefer to mate with large-clawed males. When a male has two smaller clawed males on either side of him he is more attractive to a female (because he looks relatively larger) than if he was surrounded by two larger clawed males.

This effect is known as the Ebbinghaus illusion, and suggests that males may easily manipulate their perceived attractiveness by surrounding themselves with less attractive rivals. However, there is not yet any evidence that male fiddler crabs actively move to court near smaller males.

We still know very little about how non-human animals process visual information so the perceptual effects of many illusions remains untested. There is variation among species in terms of how illusions are perceived, highlighting that every species occupies its own unique perceptual world with different sets of rules and constraints. But the 19th Century physiologist Johannes Purkinje was onto something when he said: “Deceptions of the senses are the truths of perception.”

In the past 50 years, scientists have become aware that the sensory abilities of animals can be radically different from our own. Visual illusions (and those in the non-visual senses) are a crucial tool for determining what perceptual assumptions animals make about the world around them.

Laura Kelley is a research fellow at the University of Cambridge and Jennifer Kelley is a Research Associate at the University of Western Australia. They are the co-authors of the paper ‘Animal visual illusion and confusion: the importance of a perceptual perspective‘, published in the journal Behavioural Ecology.

Bringing together significant work on all aspects of the subject, Behavioral Ecology is broad-based and covers both empirical and theoretical approaches. Studies on the whole range of behaving organisms, including plants, invertebrates, vertebrates, and humans, are welcomed.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Duck-Rabbit illusion, by Jastrow, J. (1899). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.<

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

The post Animals could help reveal why humans fall for illusions appeared first on OUPblog.