4 Stages of Character Development

When you write a first draft, there are really two novels at that point. There’s the one on the paper and there’s the one in your head and they are not the same.

I know this. But I’m experiencing it again as I’m working through this revision. In order to put on paper what is in my head, I’ve had to pay attention to feedback.

Blurry Characters

http://www.flickr.com/photos/hugovk/217155496/ My first feedback told me that my characters weren’t understood. Readers didn’t understand motivations or relationships. I worked on that by checking each scene to make sure the characters were active and the scenes goals were clear. Sometimes, I found that my main character was just an observer and had to give him a more active role. But usually, this did little to help.

Confusing Characters. The second round of feedback told me the same thing: my readers were confused. Here’s the problem: I thought that readers would understand relationships from implications in the text. But that was making them work too hard; they lost confidence in my storytelling. I realized that I had to lay it all out there, in other words, put it on the page.

Now, this does NOT mean that I put in the whole kitchen sink. No. I didn’t want to overwhelm readers with backstory. But naming a relationship was OK: “she’s my almost-adoptive-mother.” The reader still doesn’t know all of what that “almost” means but at least there’s now a frame of reference.

For the secondary character, I added a tiny bit of flashback, only 3-4 lines. It’s active, unusual, with good segues in and out of it. I almost want to take it out, because I don’t like backstory in the first chapter. But I think it’s crucial for the reader to understand the nature of what this character faces.

Deeper Characters. Finally, this third time around, my reader says my characters are deeper, motivations are clear and I’ve created great sympathy for the characters’ plight. Now, I’m just inconsistent.

Inconsistent Characters. My job on the next pass was to make sure the characters’ voices stayed consistent, the characters didn’t do or say anything that was out of character for their age or situation, and that the story itself remained consistent in tone and voice.

Exactly What I Envisioned. Well, almost, anyway. Nothing is set in stone yet, but I’m pretty pleased with how these characters are behaving right now. Pleased enough to move on and not bother my readers with this section again, but wait until there’s a whole revised novel to read.

Do your characters progress through similar stages? Blurry, confusing, deeper, inconsistent, exactly what I envisioned. Notice what was needed at each point: feedback. I only knew how well I was doing by checking in with a reader. Sometimes, especially in the early chapters, I need several rounds of feedback with my readers to make sure I’m making the needed changes. Now, with these chapters as my benchmark, I’m hoping to progress without so much feedback.

How would you describe your character’s progression through drafts? What feeds your revision cycle?

Related posts: - Opening Chapters

- Listen

- Character Bait

By: Darcy Pattison,

on 6/26/2009

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

habits of writing, revise a novel, too old, too young, authors, how to write a book, Darcy Pattison, how to, write a novel, Add a tag

What Age Do you Have to Be to Write a Novel?

The question of the perfect age to write a novel comes up sometimes when I do school visits.

Too young? At what age are you too young to write a novel and have it published? I’ve seen a 13 year old published and published well.  . .

Too old? And Richard Peck (April 5, 1934 - ) is still writing strong and many say he’s writing his best work now, including this one due out in September.

Basically, you just need to have a story you want to tell and you want to tell it badly enough that you’ll play with words over a long period of time so you get enough words written.

Strategies for Different Ages

But this also means that you must find different ways of working for your stage of life. When I first started writing, I had four kids at home and was home schooling the oldest. I carried around an ink pen to remind myself that when I had fifteen minutes free, I should write.

Today, I go to work at my office and try to work 4-6 hours per day. It’s hard to make myself stop when I come home!

Find a way to work. Find habits that let you work and revise your novel.

Post from: Revision Notes

Revise Your Novel!

Copyright 2009. Darcy Pattison. All Rights Reserved.

Related posts: - Time to Write

- Measuring Progress Poll Results

- Fearless Writing #2

By: Darcy Pattison,

on 6/25/2009

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

author, authors, J.T. Dutton, YA, Stranded, revise, submit, teen novel, write a novel, debut, how to write, Freaked, Add a tag

Introduced first in 2007, authors debuting children’s books have formed a cooperative effort to market their novels. Last year, I featured many of the stories of how the 2k8 Novels Were Revised. This is part of the ongoing stories from the Class of 2k9 authors and how they went about revising their novels.

After yesterday’s posting about when to stop revising and send in a story, J.T. Dutton’s story seemed especially appropriate. Darcy

Freaked: A Revision Story

Guest Post

by J.T. Dutton

My first book, Freaked, leapt into the world three months ago. Since then, I’ve been trying to form ideas for a short blog on revision. I’ve seized on some good thoughts for the discussion, stuff I teach in my Composition classes, ways to revise to improve sentences or arguments through better examples. I am an intense devotee of the school of write and rewrite. “Nothing is so smooth it can’t be smoother” is one of my mantras.

But when I have to talk about the revising I did on Freaked, I feel shy. I read a lot and I can think of fifty or hundred novels that I see as perfect—every sentence, word, and scene. I’d like to be a “perfect” writer too, but the fact is, I’m not. I get muddled. I have reread Freaked at least three times since it came into print, each time cringing at the number of things I would change now that I’m older and wiser. This is after revising it hundreds of times over twelve years, with the last pass conducted by some of the smartest people in the writing business—the editors and copy editors at HarperCollins.

Surgeons Don’t Get “Do Overs”

My Dad reminded me recently, when I was expressing angst about my second book, Stranded, of a quote from Albert Einstein, “perfection is the enemy of good.” My Dad is a retired surgeon. In his field, he didn’t get do-overs. He had to believe in his skills, be courageous about them. He is always stopping to offer assistance at road-side accidents. He volunteers for an ambulance service and a local fire department despite the fact that he faces liability issues as the most prepared person on the scene if something goes wrong. (This is why some doctor’s don’t stop for emergencies.)

Dad has made it a lifetime practice to do what he can, when he can. He even “vacations” every couple of years at hospital in Haiti.

Revision is a great thing, but for people like me, it can lead to obsession and excuses not to share my work. At a certain point, I have to take my dad’s advice and admit that I can’t tuck every thread, that I’m flawed, that I make mistakes, but it’s better to offer the world what skills I have than to offer it nothing at all. In this way, I guess, the writing can be interesting, individual, and courageous, rather than perfect.

A pretty worthy goal.

Thanks Dad. You are my hero.

Post from: Revision Notes

Revise Your Novel!

Copyright 2009. Darcy Pattison. All Rights Reserved.

Related posts: - Scott Franson’s Doodles

Transitions: Filling in the Time Line

I’m at a tricky place in my revision where I need a good transition. There’s a time gap. Certain events need to take place in late October and November, but I’m at about the 4th of July on the story’s time line. I need to get on with the story quickly, but it’s difficult. As it’s set up, my MC is starting middle school this fall, and that should be a big event in his life. But it’s NOT a major event, necessarily, in the story as currently told.

Yes, this is about a character, so he can be distracted for a while by this new school, but I don’t want to lose track of the events in October/November.

Create a mini-subplot that spans a couple chapters. I could think of July-October as a couple chapters of a mini-subplot. Adventure novels often do when there’s a chase sequence that spans several chapters. When the chase ends (someone is caught or someone gets away), the story returns to the main story.

Bridging events. I could think of this as needing bridging conflict, events that cause my character trouble that relates more or less to the main conflict. In this case, the events wouldn’t necessarily be a complete subplot. It could include scenes from several subplots, or it could be a small digression that shows backstory,or puts my character in a new light.

I don’t want filler material here, though. Either way, everything needs to be necessary to the story. That’s the trick! Finding bridging conflict or a mini-subplot to fill the time, but making sure it’s necessary to the story. Again, it won’t do, just to have a summary paragraph getting him to October. Going into middle school is simply too big a life event to summarize away.

Any other ways you handle major transitions or fill in gaps in your timelines?

Post from: Revision Notes

Revise Your Novel!

Copyright 2009. Darcy Pattison. All Rights Reserved.

Related posts: - Choosing subplots

- Powerful Endings

- Big Scenes

By: Darcy Pattison,

on 6/15/2009

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

word count, how to write, write a novel, page count, finish a chapter, finish an act, confidence, challenges, revision, revise, Add a tag

Last week, I asked how you measure the progress of revising your novel, or of a writing session. Here’s the results:

Word Count and Page Count Indicate Progress

Word Count edges out Page Count by one vote. It seems the ease of counting words with word processors has made Word Count one of the easiest statistics by which to measure progress.  39,704 Words! However, Page Count was only one vote behind.

Either way, it seems that we like those numbers! We can graph it, brag it, and soothe our writing beast with numbers.

Other Benchmarks of Progress

However, the other benchmarks of progress also got votes: finishing a chapter or an act, and the amount of time spent. It makes sense that not everyone does it the same way. Some write fast, others slow, so a time limit can easily work. I know that when I had four children underfoot, fifteen minutes a day was success!

Setting and Finishing Goals

Barbara Seuling says that she tries to meet the challenge of whatever faces her in a writing session and if she does that successfully, then she’s made progress. This gets away from the numbers and focuses more on the process and the content - a valuable approach.

Casey points out the obvious: we only worry about measuring progress when there’s a pause in the progress.

I think this is partly about the rhythms of the day, the rhythms of the work. But it could also be places/times when you get unexpectedly stuck! Then, we need to measure our progress to remind ourselves that we are making progress. Usually, for me, that’s why I stop and evaluate my progress: to maintain my confidence that I can continue to make progress.

Post from: Revision Notes

Revise Your Novel!

Copyright 2009. Darcy Pattison. All Rights Reserved.

Related posts: - Measuring Progress

- My Current Works in Progress

- Writing rhythms

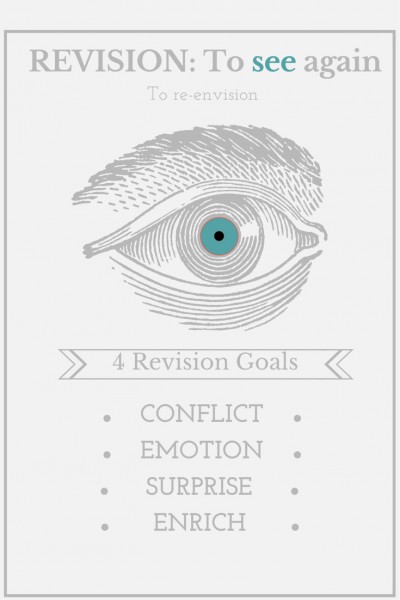

Re-Reading: The Basic Revision Strategy

I’m always amazed at how much the revision process depends on re-reading what you wrote.

It’s an obvious statement, of course. Yet, when I ask people about their revision process, re-reading is seldom mentioned. It’s one of those assumed things.

Suggestions for Re-reading to Re-envision

- Re-read an entire section, not just half a page. One editor cautioned against re-reading just half a page, because you don’t get a sense of how the revision flows with the rest of the story. It’s easy to repeat a word or phrase, to change tone, or to get slightly off-voice (like a singer gets off-key). Take it from the top of the novel or the top of the chapter; for picture books under 500 words, read the whole thing again.

- Single space the mss and print it out. This often helps me to see and hear the mss differently. Play with different fonts and print it out. Do you have a character who is feminine and delicate? Print her chapter in a script font; or, to contrast, print it in a harsh, upright font.

- Read out loud. OK. I mutter out loud. My husband is self-employed and we own an office building, so I have an office there myself. If I read out loud, it would bother others. So, I mutter out loud. Or, I put on earphones and use a software program that reads it out loud to me. (Actually, this is a good reminder: I need to use the earphones/read to me option more!) Or, I go home and read it out loud. Or, go to a park. Muttering isn’t as good as reading aloud, because you don’t get the real flow of the novel or picture book.

Someone once asked me how many times I had read through a novel. Who knows? More times than I can count, I’ve read every word. It’s the basis of all good revisions.

Post from: Revision Notes

Revise Your Novel!

Copyright 2009. Darcy Pattison. All Rights Reserved.

Related posts: - 5 Writing Tasks for Off Days

- current stories

- Paper v. Digital Revision

By: Darcy Pattison,

on 6/9/2009

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

novel submission, marketing, feedback, literary agent, critique group, critique, Darcy Pattison, contract, revise, how to write, write a novel, Add a tag

Submit, Then Revise

At our spring conference, Jen Rofe, literary agent at Andrea Brown Literary spoke about sending out manuscripts.

The one thing that surprised me was her attitude toward submission and revision. Rofe said she usually sends out a mss to about five editors. Then, depending on the feedback, she’ll often ask the writer to revise. She considers those “test submissions.”

Re-reading some of Writing the Breakout Novel Workbook by Donald Maass, I noticed the same thing. He said that Parnall Hall had to revise a mystery:

A test round of submissions suggested that the points of view in A Clue for the Puzzle Lady were improperly weighted. Hall revised, and the second round hit the jackpot. p. 47

Interesting. If literary agents regularly use this approach of test submissions then revision, it’s something to think about.  THE CRITICAL EYE Next time you send out your children’s picture book manuscript or your novel manuscript, target five publishers. If you get feedback, especially if it’s consistent in what it says, then revise before you send to five other editors.

Individual Critiques v. Group Critique

What if you don’t get personal letters from editors? I recently sent a picture book manuscript to about five different people and, without consultation with each other, four of the five mentioned a few items that needed work. Now, personally, I loved the fifth person’s comments! If she was an acquiring editor and bought the mss as is, no problem. But she’s not.

So, I have an overwhelmingly consistent opinion that something needs work.

Usually, I send to a critique group and everyone there sees the mss and it’s a group discussion. That always feels like a single opinion to me; here, I sent it privately and it’s five opinions. If those five had been in a group, the discussion may have progressed the same, but I would not be as likely to pay attention.

Will I always ask for separate critiques now? No. The group discussions are valuable. But I’m definitely adding this variation to my arsenal of revision strategies.

And yes, I’m working on revising the picture book manuscript, trying to do at least some of what these individuals asked for, while secretly hoping to find an editor who agreed with the other person!

Post from: Revision Notes

Revise Your Novel!

Copyright 2009. Darcy Pattison. All Rights Reserved.

Related posts: - Are You Still Not Tracking Submissions?

- Are you Still Submitting Before Revising?

- Q&A: How Do I Find an Editor’s Name for Submission?

By: Darcy Pattison,

on 5/15/2009

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

author, links, comics, characters, writers, children's picture books, write a novel, in a month, WriDaNoJu, Add a tag

By: Darcy Pattison,

on 4/30/2009

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

characters, child, baby, suspense, how to write, tragedy, write a novel, symbolism, jeopardy, character's death, death scene, emotional depths, fully characterized, Add a tag

Does Your Story Need a Tragic Death?

A friend was talking to me about stories in which a child dies. he asked, “Is a child’s death in a novel just a cheap narrative device?”

Well, it depends.

- Depth of Characterization. How well do we know the character? Do we know and care for the child? Does the story involve the child and his/her hopes dreams in any way? If we care for a character, we’ll be more likely to be emotionally affected by the death; and it will seem more like a part of the story and not just a cheap narrative device.

- Minor v. Major characters. If a minor child character dies, a throw-away character, the audience won’t care much, unless you’ve given the character big eyes with long eyelashes. But even that bit of specificity in the middle of a scene might not make the reader care. Because it’s a kid, it may be worth some shock value, and killing a kid simply for shock value does count as a cheap narrative trick.

- Suffering, jeopardy, suspense. Has the character suffered or does this come out of nowhere? Orson Scott Card talks about jeopardy, putting a character into a position where there is danger, and suspense, holding back only what happens next. It may be enough to put a child in increasing jeopardy, where things are dangerous, but the character must still act. Or, it may be enough to built a suspenseful scene where we worry about what happens next. Some death scenes could be replaced with either of these and still be effective

- Symbolism of a child’s death. Does the death of a child represent the loss of innocence and faith in the future? Depends. How did you set up the symbolism of THIS child? I don’t think you can generalize here, because the language used to describe the child, the actions of the plot – these can all affect symbolism. To say that a child’s death always equals loss of innocence is too glib an answer.

- Author’s Tolerance for Death. When Leslie dies in Bridge to Terabithia, it’s tragic and awful; I didn’t feel like the author had tried to manipulate my feelings, it was just a horrible accident. But I once went to a conference where an author was talking about the death of a child when it occurs in a story. The author said she hated going to schools, where kids would inevitably ask, “Why did so-and-so have to die?”

Tired of the plaintive question, she decided to never write another story for kids in which a child died. She was in the process of writing a story where a baby was sick and in the hospital. With her decision made, she started working on the next chapter and wrote, “The baby opened her eyes.”

Was she protecting herself from the questions? Was she protecting her audience from the emotional depths to which stories can take a reader? Was she protecting the baby? I don’t know.

In the end, you have to decide where you and your stories will fall: will you allow tragedies, even to the point of death; or will you hold back to protect yourself, your readers and your characters? What does the story tell you to do?

Post from: Revision Notes

Revise Your Novel!

Copyright 2009. Darcy Pattison. All Rights Reserved.

No related posts.

Do you pay attention to your audience when you write, or do you write for yourself, an audience of one?

PW’s Shelf Talker Josie Leavitt has an interesting posting on when toddlers pick out their own books. Even as toddlers, boys and girls choose books differently. Both are passionate about the books they love and both love bright colors. But boys tend toward the blue, while girls go for pink and purple.

Mouse was Mad by Linda Urban and Duck! Rabbit! by Amy Krause Rosenthall are reported to be popular with both girls and boys. They are still bright and bold, but Mouse is mostly yellow and Duck is black on white.

Leavitt’s column discusses color, something out of the scope of most writers; yet, her basic ideas applies to all of us: we should consider our audience when we write. We should think of their developmental age, reading level, interests, culture, etc.

Do you consider your audience as you write your toddler booK?

As you write and revise your preschooler’s picture book?

As you write and revise your children’s picture book aimed at school-age kids?

As you write and revise your middle grade novel for those tweens?

As you write and revise your YA novel?

As you write and revise that article for your local newspaper?

As you write (and revise) your grocery list?

As you write the letter to your child’s teacher?

As you write your blog postings?

Post from: Revision Notes

Revise Your Novel!

Copyright 2009. Darcy Pattison. All Rights Reserved.

Related posts: - Audience

- Audience Considerations

- A Real Audience

Learn to Listen to Critiquers

Listening to critiques is hard!

I have to remind myself that writing is communication, with a writer and a reader. When I get feedback, what I’m really doing is checking to see if I communicated what I wanted to. Well, no. I didn’t.

I have two choices:

- Ignore the feedback. This guarantees that a chunk of readers will not understand my story, my essay, my attempt at communicating.

- Clarify through revision. Revision is the process of clarifying the communication.

For fiction, this means partly that the reader has an internalized concept of story and your story must fit that concept, at least to some degree. You can break expectations, of course, and often the best novelists do, but the novel must fit some of these conventions, or communication breaks down.

Plot holes. The reader’s reasoning process say, uh-oh, that wouldn’t have happened that way. Or, you can’t have that happen at the same time as this other event. Whatever - the story violates the reader’s sense of what is possible.

Character holes. The reader just doesn’t believe this is a person, but just a collection of characteristics. Successful novels put together characteristics, emotions, actions, reactions in such a way that the reader believes.

Feel free to disagree with any and every piece of feedback you get. But only after you’ve listened, and thought, and thought and tried to make sure your communication is reaching your readers.

Post from: Revision Notes

Revise Your Novel!

Copyright 2009. Darcy Pattison. All Rights Reserved.

Related posts: - Revision: Understanding critiques

- Feedback

- When to Ask for a Critique

By: Darcy Pattison,

on 4/20/2009

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

agent, author, novel, authors, revision, psychology, how to write, write a novel, 2k9, write a book, Add a tag

Introduced first in 2007, authors debuting children’s books have formed a cooperative effort to market their novels. Last year, I featured many of the stories of how the 2k8 Novels Were Revised. This is part of the ongoing stories from the Class of 2k9 authors and how they went about revising their novels.

Will This Novel Revision Change My Vision of the Story?

by

Cheryl Renee Herbsman

Revision is such an interesting subject. In college and graduate school (in psychology) it was always something with which I struggled. Revision felt to me like I just had to change what the professor wanted me to change to please him/her. And as I did that, I found that the story or novel felt less and less my own.

Agents say, “Drop that character.” The first literary agency that expressed interest in my novel, Breathing, asked me to do a revision. They made a number of suggestions and I worked hard at incorporating the revisions I believed would make the book stronger (such as developing the character of Mama further). But they also wanted me to drop one of the key characters (DC) from the novel. And that was something I just couldn’t do. While they praised my work on the revision, they rejected the novel. This made me wonder if I was going to have to give up my vision for the book, but I pressed on.

Next agent loves novel, as is - and sells it! The next agent loved it as is and sent it out to publishing houses immediately. The book sold quickly, which was very exciting.

Editor requests revisions. When my editor sent a revision letter for my book, I became nervous. What would happen if I didn’t make every change? Would it be tolerated? I decided to hope for the best.

Will Herbsman’s vision of the novel stick? I made all the revisions I believed strengthened the novel (such as giving Savannah a summer job so she spent less time moping, revising the timeline for the program in the mountains so it made more sense, increasing Jackson’s passion for his painting). And I didn’t make the other changes in my book – the ones that just didn’t feel right to me on some gut level (such as removing Savannah’s visions or her saving Jackson from the train). And I sent it in. And . . .

. . . the editor loved it. And she told my agent how impressed she was that I stuck to my own vision of the story and didn’t make every change she suggested. That felt huge to me.

So what I learned with this first book is that it’s important to make changes, yes, but it’s also crucial to be the one holding the vision of the story that gave itself to you.

Post from: Revision Notes

Revise Your Novel!

Copyright 2009. Darcy Pattison. All Rights Reserved.

No related posts.

By: Darcy Pattison,

on 4/14/2009

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

question, characters, plot, revision, revise, setting, chapters, cut, write a novel, Add a tag

10 Ways to Start the Process of Re-Envisioning

How do you start revisions? You’ve got a great draft, and it’s pretty settled in your mind that this is how the story happens. BUT, readers aren’t thrilled with it. Editors and agents pass it by with a nice personal letter. Great, you think. There’s something here, but it’s not quite right. How do you start the process of re-envisioning such a story?

Some suggestions:

- Add, subtract or combine characters. Add a new best friend, or a new villain. Take out a character who has supported the antagonist, leaving the antagonist to his/her own devices. Combine two friends into one, especially when it will combine contrasting characteristics in a quirky way.

- Give a character a definite attitude. Find a certain scene that troubles you and do this: give one of the characters a definite attitude about what is happening. The character loves the current event, despises it, wishes his sister were here to deal with it, - anything. Give the second character a competing, but not opposite point of view: this character also knows the sister would do a better job of things, but is determined to do it herself, without sister’s help. Now, re-write, focusing especially on the dialogue.

- Switch POV. Write a scene from a different point of view and see where it takes you.

- Change setting. Put the scene in a different setting, a different time of day or season. What changes? What is possible in the desert is not possible on the beach! What difference does this setting make to the story?

- Cut the first three chapters. Begin the story at chapter four and make it work; don’t allow any back story to come into the story until page 100.

- Question assumptions about characters. Yes, Snively Whiplash is still the villain, but maybe he sings rock music and you never even knew it. And he’s striking back right now against your character because at a Karaoke, the antagonist didn’t recognize Whiplash in his disguise and actually laughed at his singing. OK. A bit melodramatic (Snively does that to a story!), but you get the idea. Have you assumed a character is all good or all bad? Find the opposite quality in him or her. Question something basic about one or more characters and carry it to the logical extreme.

- Raise the Stakes. How can you make the outcome of a scene matter more to the antagonist or protagonist? The lost necklace belonged to Melanie’s grandmother, who brought it from Poland when she fled the Nazi regime. It had been given to her by her fiance before he went off to war and was never seen again. THAT is the missing necklace and it matters deeply to Melanie, who loved that grandmother. Or, make the stakes broader, with wider effects: the fire set by Jimmy and Prissy in the woods has spread and now threatens the whole community.

- Rethink the Plot Complications. What obstacles does the main character confront? Can you add one more, in the form of a subplot? Try to change the obstacles in intensity, scale, or sheer amount of aggravation. Instead of one puny kid objecting to the character’s call as a soccer referee, let the biggest kid argue the call; or let the whole team gather round our poor character and let him talk his way out of that one! Or, instead, the whole team heckles him throughout the rest of the game, nothing enough to get them thrown out, but enough to aggravate.

- Drastic Rewrite #1: Retype the whole manuscript, with the idea that you must change something on every page as you rewrite. But when a revision takes off, follow it and give it free rein.

- Drastic Rewrite #2: Put the manuscript in a drawer and open a new computer file or take out new notebook paper. Tell the story again, without looking at the first telling. Do this chapter by chapter if you have to until some new idea takes hold, and then go with it.

Caution: NEVER delete an old manuscript or type over it. always keep a copy, in case you need to go back to it. Often changes go too far and you need to back track some. The previous drafts are helpful to remind you of the options you have already explored and which worked and which didn’t.

Post from: Revision Notes

Revise Your Novel!

Copyright 2009. Darcy Pattison. All Rights Reserved.

Related posts: - Characters That Count

- 3 Ways to Salvage a Scene

- Talk, revise, streamline, investigage, read, envision, play

By: Darcy Pattison,

on 3/6/2009

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

revision, retreat, contracts, revise, how to write, writing career, write a novel, negotiate, shrunken manuscript, Add a tag

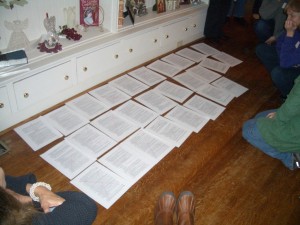

Shrunken Manuscript at Illinois Novel Revision Retreat Take Time to Revise

Jim Danielson, who attended last weekend’s Illinois retreat, has also posted a picture of a shrunken manuscript.

Here are other links for the Shrunken Manuscript technique:

Intensive feedback, like you get in a weekend retreat, can be overwhelming and after a while, I know I would tend to shut down and just nod and not understand what someone was saying. It’s important to take time later to rethink all the comments you wrote down.

Jim is planning to use the shrunken manuscript to check several issues in his story. Likewise, I know other participants are rereading their manuscripts and hearing the voices of their critique partners in their heads.

Revisions take time: time to give up something you clung to even though it wasn’t working, time to re-envision your story, time to work out the details of the changes needed, time to fall in love with your characters again, time to do the work needed.

Writing is a Business

I also heard from a participant in last month’s Oklahoma picture book retreat. The last session there was about the career of writing. We discussed the realities of submission, contracts, and the fate of midlist books. I suggested the writers read, The Good Girl’s Guide to Negotiations. (Only two participants were men!) I also heard from a participant in last month’s Oklahoma picture book retreat. The last session there was about the career of writing. We discussed the realities of submission, contracts, and the fate of midlist books. I suggested the writers read, The Good Girl’s Guide to Negotiations. (Only two participants were men!)

Too many times, I see women writers play tea party in negotiations, to their own detriment.

So - one writer wrote to say that an agent had given her a personal rejection letter. Not the first time this has happened. But it’s the first time the writer immediately sent a second manuscript, which addressed the concerns of the letter in fresh ways.

Yes! Stand up for yourself and your career! No one cares about it as much as you do and if you don’t push for acceptance of your stories, why should anyone else?

By: Darcy Pattison,

on 12/11/2008

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

openings, writing techniques, story plot, write a novel, agent, query, writing tips, novel, agents, first chapter, write, foreshadowing, opening lines, Add a tag

The holidays and the end of the year are bringing out the generous nature of agents!

The 2nd Sort-of-Annual Stupendously Ultimate First Paragraph Challenge

- Deadline: 7pm. EST, Thursday, December 11, 2008.

- Who: Literary agent Nathan Bransford, Curtis Brown, San Francisco office

- What: Post the first paragraph of your WIP and compete for the prize of a partial critique, query critique or a 15 minute phone call.

- How: Skip over to Bransford’s website and post your paragraph in the comments.

- Warning: The competition is stiff. With 10 hours left, there were 1176 comments/paragraphs.

- Attention: This is a learning opportunity. Read through at least some of these paragraphs and see which you like and which you don’t. What grabs your attention? Check back when Bransford posts the winners and vote on the finalist. Do you agree with his choices or not? Why or why not?

For more on opening lines:

Take a Holiday Break from Queries and Submit a Chapter Instead

- Dates: December 15 to January 15

- Who: Firebrand Literary

- What: Firebrand agents want to read your first chapter and will forego the usual query. This is a big task for those agents and a great opportunity for writers of all kinds. For those of you who have never got a request for a partial (probably because your query was weak), this is your golden chance. Let your writing speak for itself.

- How: Go to the Query Holiday posting on Firebrand’s website.

For more on opening chapters:

|

.

.