new posts in all blogs

Viewing Blog: The Chicago Blog, Most Recent at Top

Results 26 - 50 of 2,009

Publicity news from the University of Chicago Press including news tips, press releases, reviews, and intelligent commentary.

Statistics for The Chicago Blog

Number of Readers that added this blog to their MyJacketFlap: 8

By: Kristi McGuire,

on 5/26/2016

Blog:

The Chicago Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Add a tag

The Sykes-Picot Agreement, ratified on May 16, 1916, was a concord developed in secret between France and the UK, with acknowledgement of the Russian Empire, that allocated control and influence over much of Southwestern Asia, carving up and establishing much of today’s Middle East, along with Western and Arab sociopolitical tensions. The real reason for the divide? The region’s petroleum fields, and the desire to share in its reserves, but not its pipelines. Rachel Havrelock’s book River Jordan: The Mythology of a Dividing Line considers the implications of yet another border in the region, the river that defines the edge of the Promised Land in the Hebrew Bible—an integral parcel of land for both the Israeli and Palestinian states. With her expertise in the ideologies that undermine much cartography of the region (her book includes a map of the Sykes-Picot Agreement’s splitting of territories), Havrelock understands how the demarcation of influence was central to the production of very specific oil-producing nation states.

In a recent piece for Foreign Affairs, appearing a century after the Sykes-Picot Agreement, Havrelock writes about the potential for the region to remake itself, in the self-image of its peoples and their local resources:

The dissolution of oil concessions could hold the key to this transformation. Consider the Kurdish case. Following the Second Gulf War, private oil companies flocked to Iraq. Iraq’s national oil company reserved the right to pump existing wells with partners of its choosing, but local bodies such as the Kurdistan Regional Government were allowed to explore new wells and forge their own partnerships—a boon to the Kurdish economy.

Kurdish oil shares made all the difference when ISIS emerged in 2014. The largely effective Kurdish Peshmerga fight against ISIS owes to Kurds’ desire to protect not just their homeland but also the resources within it. Kurds harbor longstanding desires for autonomy, but their jurisdiction over local oil is a form of sovereignty—over resources rather than territory—that models a truly post‑Sykes–Picot Middle East. Because Sykes–Picot divided territory in the name of extracting and transporting oil to Europe, reforming the ownership of oil is the first step in dissolving the legacy of colonial administration and authoritarian rule.

Ideally, people across the Middle East should hold shares in local resources and have a say in their sale, use, and conservation. In an age of increased migration, this principle could help people inhabit new places with a sense of belonging and stewardship. Of course, local officials will still need to partner with global firms to drill, refine, and export oil, but such contracts will work best when driven by local needs rather than corporate profits. The Kurdish case proves that local stakeholders will raise an army where oil companies will not.

To read Havrelock’s piece in full at Foreign Affairs, click here.

To read more about River Jordan, click here.

From “Live through This,” by Catherine Hollis, her recent essay at Public Books on how much of our own lives we construct when we read and write memoirs:

In The Dead Ladies Project: Exiles, Expats, and Ex-Countries, Jessa Crispin, the scrappy founding editor of Bookslut and Spolia, finds herself at an impasse when a suicide threat brings the Chicago police to her apartment. She needs a reason to live, and turns to the dead for help. “The writers and artists and composers who kept me company in the late hours of the night: I needed to know how they did it.” How did they stay alive? She decides to go visit them—her “dead ladies”—in Europe, and leave the husk of her old life behind. Crispin’s list includes men and women, exiles and expatriates, each of whom is paired with a European city. Her first port of call is Berlin, and William James. Rather than explicitly narrating her own struggle, Crispin focuses on James’s depressive crisis in Berlin, where as a young man he learned how to disentangle his thoughts and desires from his father’s. Out of James’s own decision to live—“my first act of free will shall be to believe in free will”—the rest of his life takes shape. Crispin reconstructs what it might have felt like to be William James before he was William James, professor at Harvard and author of The Varieties of Religious Experience. If he can live through the uncertainty of a life-in-progress, so too might she.

But not before checking in with Nora Barnacle in Trieste, Rebecca West in Sarajevo, Margaret Anderson in the south of France, W. Somerset Maugham in St. Petersburg, Jean Rhys in London, and the miraculous and amazing surrealist photographer Claude Cahun on Jersey Island. Through each biographical anecdote, each place, Crispin analyzes some issue at work in her own life: wives and mistresses, revolutionaries with messy love lives, and the problem of carting around a suicidal brain. Crispin travels with one suitcase, but a good deal of emotional baggage. While she focuses on each subject’s pain, what she’s seeking is how these writers and artists alchemized their suffering into art, and how that transmutation opens up an individual’s story to others. . . .

In the end, learning how other women and men decided to live helps Crispin decide that suicide is a failure of imagination. “Here is something else you could do,” Crispin’s ladies tell her; here is some other way to live.

To read the piece in full at Public Books, click here.

To read more about The Dead Ladies Project, click here.

By: Kristi McGuire,

on 5/20/2016

Blog:

The Chicago Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

Barry Schwabsky on Kristin Ross’s May ’68 and Its Afterlives at Hyperallergic:

Okay, but when she dismisses a detractor’s charge that “nothing happened in France in ’68. Institutions didn’t change, the university didn’t change, conditions for workers didn’t change — nothing happened,” I have to wonder. Yes, something happened in the moment, with echoes that went on resonating for a few more years — but really, what long-term upshot did it have? That it’s hard to point to one is sobering, and to brush that aside seems to me too much like turning an uprising into (an unfortunate understanding of) a work of art: useless, complete in and of itself, to be admired, wondered at, and taken as exemplary. From May ’68 to the Arab Spring and Occupy, these beautiful apparitions, so easily quashed, can seem in retrospect a great argument for Leninism, and I can’t help sympathizing with, of all people, the embittered Maoist veteran of May, quoted by Ross, who came away from it with the lesson: “Never seize speech without seizing power.” Except that anyone who thinks they know how to do that is probably deluded.

To read the Hyperallergic piece in full, click here.

To read more about May ’68 and Its Afterlives, click here.

By: Kristi McGuire,

on 5/18/2016

Blog:

The Chicago Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

Via an excerpt from the postscript to Roger Ebert’s Two Weeks in the Midday Sun, up at Esquire:

My wife and I sit all by ourselves at the table for 10, awaiting Monsieur Scorsese. Around us, desperate and harried waiters ricochet from table to table with steaming tureens of fish soup and groaning platters of whole lobster, grilled fish, garlic paste, crisp toast, boiled potatoes, and the other accoutrements of a bowl of bouillabaisse. To occupy an unused table in a busy French restaurant is to be the object of dirty looks from every waiter; if you are going to be late, be late—don’t be the ones who get there early and take the heat.

Around us, tout le Hollywood slurps its soup. There is Rob Friedman, second in command at Paramount. Over there is Woody Harrelson, who explains he partied till 6 A.M. and then slept two hours, and that was 15 hours ago. He wears the same thoughtful facial expression that his character in Kingpin did when his hand was amputated in the bowling ball polisher. Next to him is Milos Forman, who directed him in The People vs. Larry Flynt. Across from him is director Sydney Pollack (Tootsie). Across from him is director John Boorman (Deliverance). All of these people regard their bouillabaisse like poker players with a good hand.

“It is no more, sorry, impossible! You must now to go outside!” cries the owner. He wrings his hands with anguish. “The people who are waiting, they are very angry! I cannot wait them no more! Impossible! Monsieur Scorsese plus tard! Monsieur DeNiro, etc., etc.”

We are banished from the table and go to wait outside in the road. Tétou is so small that you are either seated at a table or standing on the curb dodging Renaults and motorbikes. The Scorsese table has been given to angry patrons who have been waiting outside for, one gathers, days or weeks. I picture them in pup tents. Immediately after we are evicted, Monsieur Scorsese arrives—but not in time to beat out the new occupants of his table, who sit down with the air of wronged exiles returning to their ancestral homeland.

“Jeez, what are we, 15 minutes late?” asks Scorsese. His party includes his agent Rick Nicita, his collaborator Rafael Donatello, his friend Helen Morris, his agent Manny Nunez, Touchstone execs Jordi Ross and Mimi Hare, his producer Barbara de Fina, and his assistant Kim Sockwell. Counting us, there are 11, not 10. No problem, since there is no room for any of us.

Four of us are parked at a table in the corner while the rest of the party hovers uncertainly beside the traffic lanes. We are promised seating in five minutes. Well, not precisely five minutes, but cinq minutes, which is a French expression translating as “five unspecified units of time.”

I do my imitation of the restaurateur saying “impossible.” Scorsese is delighted: “He sounds exactly like Susan Alexander’s vocal coach in Citizen Kane, telling Orson Welles that his wife will never be an opera singer.”

To read the excerpt in full at Esquire, click here.

To read more about Two Weeks in the Midday Sun, click here.

By: Kristi McGuire,

on 5/16/2016

Blog:

The Chicago Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

From Michelle Dean’s profile of Jessa Crispin for the Guardian:

Staying outside of that mainstream, Crispin said, had some professional costs. “We didn’t generate people that are now writing for the New Yorker,” Crispin said. “If we had, I would have thought that we were failures anyway.” She’s bored by the New Yorker. In fact, of the current crop of literary magazines, she said only the London Review of Books currently interested her, especially articles by Jenny Diski or Terry Castle. Of the New Yorker itself, she said: “It’s like a dentist magazine.”

Crispin’s general assessment of the current literary situation is fairly widely shared in, of all places, New York. It is simply rarely voiced online. Writers, in an age where an errant tweet can set off an avalanche of op-eds more widely read than the writers’ actual books, are cautious folk.

And Crispin can’t stand the way some of these people have become boosters of the industry just at the moment of what she sees as its decline. “I don’t know why people are doing this, but people are identifying themselves with the system,” Crispin said. “So if you attack publishing, they feel that they are personally being attacked. Which is not the case.”

It’s not that she doesn’t understand these writers’ reasoning. “Everything is so precarious, and none of us can get the work and the attention or the time that we need, and so we all have to be in job-interview mode all of the time, just in case somebody wants to hire us,” Crispin added. “So we’re not allowed to say, ‘The Paris Review is boring as fuck!’ Because what if the Paris Review is just about to call us?” The freedom from such questions is something Crispin personally cherishes.

To read more, visit the Guardian here.

To read more about The Dead Ladies Project, click here.

By: Kristi McGuire,

on 5/13/2016

Blog:

The Chicago Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

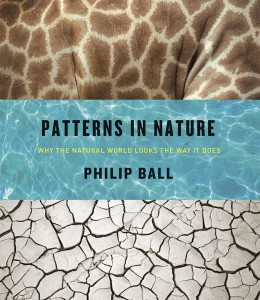

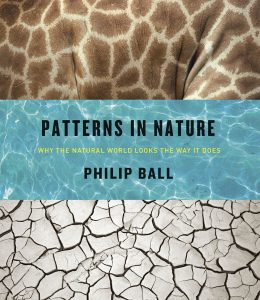

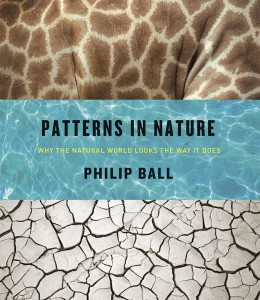

Publishers Weekly already christened Philip Ball’s Patterns in Nature: Why the Natural World Looks the Way It Does as the “Most Beautiful Book of 2016.” In a recent interview he did with Smithsonian Magazine, Ball lets us in on why, exactly we’re so drawn to the idea of patterns and their visual manifestations, as well as what let him to follow that curiosity and write the book. Read an excerpt after the jump.

***

What exactly is a pattern?

I left it slightly ambiguous in the book, on purpose, because it feels like we know it when we see it. Traditionally, we think of patterns as something that just repeats again and again throughout space in an identical way, sort of like a wallpaper pattern. But many patterns that we see in nature aren’t quite like that. We sense that there is something regular or at least not random about them, but that doesn’t mean that all the elements are identical. I think a very familiar example of that would be the zebra’s stripes. Everyone can recognize that as a pattern, but no stripe is like any other stripe.

I think we can make a case for saying that anything that isn’t purely random has a kind of pattern in it. There must be something in that system that has pulled it away from that pure randomness or at the other extreme, from pure uniformity.

Why did you decide to write a book about natural patterns?

At first, it was a result of having been an editor at Nature. There, I started to see a lot of work come through the journal—and through scientific literature more broadly—about this topic. What struck me was that it’s a topic that doesn’t have any kind of natural disciplinary boundaries. People that are interested in these types of questions might be biologists, might be mathematicians, they might be physicists or chemists. That appealed to me. I always liked subjects that don’t respect those traditional boundaries.

But I think also it was the visuals. The patterns are just so striking, beautiful and remarkable.

Then, underpinning that aspect is the question: How does nature without any kind of blueprint or design put together patterns like this? When we make patterns, it is because we planned it that way, putting the elements into place. In nature, there is no planner, but somehow natural forces conspire to bring about something that looks quite beautiful.

To read more about Patterns in Nature, click here.

By: Kristi McGuire,

on 5/11/2016

Blog:

The Chicago Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

Sara Goldrick-Rab, recently named one of *the* indispensable academics to follow on Twitter by the Chronicle of Higher Education, will publish her much-anticipated Paying the Price: College Costs, Financial Aid, and the Betrayal of the American Dream this fall. Needless to say, the book couldn’t be more timely—and important—to the continued conversation and policy debates surrounding the hyperbolic costs associated with American higher education. The book, which draws on Goldrick-Rab’s study of more than 3,000 young adults who entered public colleges and universities in Wisconsin in 2008 with the support of federal aid and Pell Grants, demonstrates that the cost of college is no longer affordable, or even sustainable—despite the assistance of federal, state, and local aid, the insurmountable price of an undergraduate degree leaves a staggering number of students crippled by debt, working a series of outside jobs (sometimes with inadequate food or housing), and more often than not, taking time off or withdrawing before matriculation. One of Goldrick-Rab’s possible solutions, a public sector–focused “first degree free” program, deserves its own blog entry.

In the meantime, here’s an excerpt from a piece by Goldrick-Rab recently published at the Washington Post, which provides human faces to some of the data circulating around the central issues:

When he runs out of options, some nights Sam sleeps in his car. The students he attends class with at Milwaukee Area Technical College don’t know — his bright smile, carefully assembled outfits, and optimistic chatter are all they see. But his friend Angel understands; he and his three sisters are barely able to make it day to day since their mom was deported. His older sister works full-time to support them and their elderly grandmother while Angel works on his associate’s degree.

Over at Madison College, Jenna has been taking a class or two at a time for nearly four years. She can’t do more while raising two children on her own, though food stamps help a bit. She’s frustrated and wishes it would be easier to finish her degree, so that she could get a better job and secure a better life for her family.

Every year about three in 10 college students leave college without a degree. Many receive financial aid and also work, but the prices are so high that they can’t make ends meet. Even at community colleges, their basic needs go unmet: food runs short, and safe housing is hard to come by.

Sam, Angel and Jenna have managed to stay in college despite the odds, and at the end of April they joined more than 150 people from around the country at the first-ever national meeting about college food and housing insecurity. Hosted by the Wisconsin HOPE Lab at Milwaukee Area Technical College, the #RealCollege convening was intended to inspire action. At the end of 2015, my team at the Lab published an op-ed in the New York Times describing our latest research about the prevalence of material hardship among the nation’s community college students.

Data from a survey of more than 4,000 students at 10 institutions around the country revealed that one in five was hungry, and 13 percent were homeless. Sadly, we weren’t surprised. Since 2008, we have been tracking food and housing insecurity in Wisconsin, while a handful of other scholars around the nation have been doing the same. It’s become increasingly clear that rising child poverty rates in the United States, coupled with broadened college enrollment, means that the same challenges confronting elementary and secondary schools now face colleges and universities too.

To read the Washington Post piece in full, click here.

For more about Paying the Price, click here.

By: Kristi McGuire,

on 5/9/2016

Blog:

The Chicago Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

Just in time for this week’s opening days of the 2016 Cannes Film Festival, we’re thrilled to publish Roger Ebert’s Two Weeks in the Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook, with a new foreword by Martin Scorsese and a new postscript. You can read more about the book below, and for the next month, download a free e-book version of Ebert’s Bests, which combines a selection of Ebert’s beloved “10 Bests” lists with the story of how he became a film critic.

***

A paragon of cinema criticism for decades, Roger Ebert—with his humor, sagacity, and no-nonsense thumb—achieved a renown unlikely ever to be equaled. His tireless commentary has been greatly missed since his death, but, thankfully, in addition to his mountains of daily reviews, Ebert also left behind a legacy of lyrical long-form writing. And with Two Weeks in the Midday Sun, we get a glimpse not only into Ebert the man, but also behind the scenes of one of the most glamorous and peculiar of cinematic rituals: the Cannes Film Festival.

More about people than movies, this book is an intimate, quirky, and witty account of the parade of personalities attending the 1987 festival—Ebert’s twelfth, and the fortieth anniversary of the event. A wonderful raconteur with an excellent sense of pacing, Ebert presents lighthearted ruminations on his daily routine and computer troubles alongside more serious reflection on directors such as Fellini and Coppola, screenwriters like Charles Bukowski, actors such as Isabella Rossellini and John Malkovich, the very American press agent and social maverick Billy “Silver Dollar” Baxter, and the stylishly plunging necklines of yore. He also comments on the trajectory of the festival itself and the “enormous happiness” of sitting, anonymous and quiet, in an ordinary French café. And, of course, he talks movies.

Illustrated with Ebert’s charming sketches of the festival and featuring both a new foreword by Martin Scorsese and a new postscript by Ebert about an eventful 1997 dinner with Scorsese at Cannes, Two Weeks in the Midday Sun is a small treasure, a window onto the mind of this connoisseur of criticism and satire, a man always so funny, so un-phony, so completely, unabashedly himself.

To read more about Two Weeks in the Midday Sun, click here.

By: Kristi McGuire,

on 5/6/2016

Blog:

The Chicago Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

From a recent profile of Deirdre McCloskey in the Chronicle of Higher Education:

As the University of Chicago Press plans to release next month the final volume of McCloskey’s ambitious trilogy arguing that bourgeois values, rather than material circumstances, catalyzed the past several centuries’ explosion in wealth, her gender change may be the least iconoclastic thing about her. A libertarian with tolerance for limited welfare interventions by government, an economist who critiques the way her colleagues apply statistics and mathematical models, a devout Christian who emphasizes charity and love but within free-market strictures, a learned humanist politically to the right of many of the scholars who inspire her, McCloskey is a school of one.

“Everybody regards her as a superb intellectual and somebody who has for many years disregarded disciplinary boundaries,” says the economic historian Joel Mokyr, of Northwestern University. . . .

“I’ve seen so many academic careers end not with a bang but with a whimper. I thought that would happen to me,” she says. “I am so glad that in my old age I have found a project that uses what talents I have.”

McCloskey’s singularity can be traced to her lifelong journeys across gender, politics, academic outlook, and religious viewpoint. She has shifted from male to female, from left to right, from narrow, math-centered economist to wide-ranging interdisciplinarian, and from secular to progressive Episcopalian. Those four strands have intertwined and influenced one another. In the experience of a lesser and less determined mind, they might have added up to flakiness or hopeless confusion. But even McCloskey’s critics tend to venerate two or three phases of her varied career, if not all of them, and the word “brilliant” comes up not infrequently.

McCloskey is wry about the changes. “I seem to be condemned to spending the second half of my career contradicting the first half,” she tells a trio of graduate students in an informal seminar at her home one evening when the rest of the country is watching the Super Bowl.

It’s a good line, but the truth is more complicated. Each stage was necessary to the next, built on the models and knowledge of the period before, but improved as she confronted her disillusionment when those models proved fallible or at least insufficient to explain the complex world around her. The shifts, some reflected over the course of her 17 books, weren’t fickle changes of mind but a pentimento layering of experience. “I think that’s true of all our lives,” she says, “don’t you?”

***

Join McCloskey for a discussion of her latest book Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World, Friday, May 6th, 6PM, at the Seminary Co-op Bookstore, 5751 South Woodlawn, Chicago, IL 60637.

To read more about Bourgeois Equality, click here.

By: Kristi McGuire,

on 5/4/2016

Blog:

The Chicago Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

“Diamond Dave and the Porcupine Hollow”

An excerpt from the Prologue to America’s Snake by Ted Levin

***

Why would Alcott Smith, at the time nearly seventy, affable and supposedly of sound mind, a blue-eyed veterinarian with a whittled-down woodman’s frame and lupine stamina, abruptly change his plans (and clothes) for a quiet Memorial Day dinner with his companion, Lou-Anne, and drive from his home in New Hampshire to New York State, north along the western rim of a wild lake, to a cabin on a corrugated dirt lane called Porcupine Hollow? Inside the cabin fifteen men quaffed beer, while outside a twenty-five-inch rattlesnake with a mouth full of porcupine quills idled in a homemade rabbit hutch. It was the snake that had interrupted Smith’s holiday dinner. Because of a cascade of consequences there aren’t many left in the Northeast: timber rattlesnakes are classified as a threatened species in New York and an endangered species everywhere in New England except Maine and Rhode Island where they’re already extinct. They could be gone from New Hampshire before the next presidential primary. Among the cognoscenti it’s speculated whether timber rattlesnakes ever lived in Quebec; they definitely did in Ontario, where rattlesnakes inhabited the sedimentary shelves of the Niagara Gorge but eventually died off like so many failed honeymoons consummated in the vicinity of the falls.

That rattlesnakes still survive in the Northeast may come as a big surprise to you, but that they have such an impassioned advocate might come as an even bigger surprise. Actually, rattlesnakes have more than a few advocates, both the affiliated and the unaffiliated, and as is so often the case, this is a source of emotional and political misunderstandings, turf battles and bruised egos. As you may have guessed already, Alcott Smith is a timber rattlesnake advocate, an obsessive really, who inhabits the demilitarized zone between the warring factions. How else to explain this spur-of-the-moment, four-hour road trip?

By the time Smith arrived, the party had been percolating for a while. Larry Boswell opened the door. As he spoke, a silver timber rattlesnake embossed on an upper eyetooth caught the light. Boswell owned the cabin and access to a nearby snake den, a very healthy one, where each October the unfortunate rattlesnake outside, following its own prehistoric biorhythms, had crawled down a crevice and spent more than half the year below the frost line dreaming snake dreams. Porcupines also favor sunny slopes, which likely is how the two met, one coiled and motionless and the other blundering forward. You’d think that after thousands of years of cohabitation on the sunny, rocky slopes of the Northeast, rattlesnakes and porcupines might have worked things out, but not so. No doubt, both animals instinctually took a defensive stance, and whether the snake struck and quills came out, or the startled porcupine lashed the snake with its pincushion tail, both had been severely compromised.

Without Smith’s help, the rattlesnake might have been doomed to starve as the quills festered. Ailing snakes die slowly, very slowly. One western diamondback is reported to have survived (and grown longer) in a wooden box for eighteen months without food and water, and a timber rattlesnake from Massachusetts lived twelve months (in and out of captivity) with its face consumed by a white gelatin-like fungus, a Quasimodo in the Blue Hills.

The cabin was small, dank, poorly lit. There wasn’t a sober individual in the group. Lou-Anne thought of Deliverance, and all evening she stood by the front door. Smith examined the snake and found fifteen quills embedded inside its mouth, which curled back a corner of the upper lip and perforated the margin of the glottis, gateway to the lungs, compromising both the snake’s breathing and its eating while protecting the outside world from the business end of the fabled, hollow (and grossly misunderstood) fangs. Essentially, the snake’s mouth had been pinned open.

Although this was a rattlesnake-tolerant (if not friendly) group, Smith wasn’t about to trust any of their less-than-steady hands to hold the animal. With imaginary blinkers on, Smith worked on a cleared-off coffee table in the middle of the cabin, with the overly supportive crowd keyed to every nuance. Smith gripped the head with one hand and pulled quills with the other, while the snake’s dark, thick torso sluggishly undulated across the coffee table. Slowly, methodically, he plucked each quill with a hemostat, and the men, who had tightened into a knot around the coffee table, cheered, toasted, chugged. After the last quill was pulled, the ebullient crowd roared approvingly, and the snake was returned to the hutch. Eight-years later, Lou-Anne, still jazzed by the potpourri of emotions, intensity, and images of that night, remembers feeling “relieved to have left there alive” as the couple returned home on the morning side of midnight.

*

The timber rattlesnake had been discovered several days before the tabletop surger y. Three of the unaffiliated herpetological adventurers — a couple from Connecticut and a man from northern Florida — had concluded an annual spring survey of the bare-bone outcrops behind the cabin. There, in the remote foothills above the shores of a narrow valley, where a wild brook strings together a run of beaver ponds, is one of the most isolated series of rattlesnake dens in the Northeast, perhaps in the entire country. (The word infested might come to more discriminatory minds.) For me, seeing those small, gorgeous pods of snakes basking in the October sunshine is stunning, a natural history right of passage, sort of like a bar mitzvah without the rabbi.

Beside the rattlesnakes, the trio found a fresh porcupine carcass in the rocks, unblemished, and on their way back down the mountain, they found the quilled snake, coiled loosely in a small rock pile one hundred fifty feet behind the cabin, last snake of the afternoon. The rock pile was at the base of a corridor, a bedrock groove in the side of the mountain that rattlesnakes use as a seasonal pathway from the den to the wooded shore and back. The cabin’s unkempt backyard is a veritable (and historic) snake thoroughfare. One of these three, a man who calls himself Diamondback Dave, thought he could pull the quills. Well known in the small, fervid circle of snake enthusiasts, Diamondback Dave maintains the website Fieldherping.com, where, among scores of photographs posted of himself (and a few friends) holding various large and mostly venomous snakes, you can view a full-frame picture of his bloody hand, the injury compliments of a recalcitrant banded water snake. You can also read synopses of field trips and random journalistic entries like this one:

I had a meeting with the director of a wildlife conservation society to discuss strategies on protecting rattlesnake populations in Eastern North America. What turned out was a weird combination of trespass warnings and a lengthy and unnecessary lecture on going back to school and finishing my degree, so that I could make 80,000 a year . . . welcome to the new age of Academic Wildlife Exploitation! . . . Business as usual.

Although in the spring of 2003, Diamondback Dave had never “pinned” a snake, a term that means immobilizing a venomous reptile’s head against the ground using any of a number of implements — snake hook, snake stick, forked branch, golf putter, and so forth — he convinced his two friends that he knew what he was doing. He did. Once the rattlesnake was pinned, Diamondback Dave directed his female companion to hold the body. Three visible quills protruded several inches from a corner of the snake’s mouth, fixed like miniature harpoons with their barbed tips. Dave’s efforts to pull them proved fruitless, however; not wanting to risk further injury to the snake, he released it.

On their way back to the car, they reported the incident to Boswell, who returned the following day and transferred the rattlesnake from rock pile to rabbit hutch. In his spare time, Boswell taught police officers and game wardens how to safely catch and relocate nuisance snakes, and he had been issued a permit by New York Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) to harbor them on a temporary basis. This snake needed more than he could offer, though, so the next afternoon, Boswell phoned Alcott Smith.

*

After surgery, the timber rattlesnake recuperated in the hutch on Larry’s side of the bed. Three weeks later, when it was able to swallow a chipmunk, the snake was returned to the rock pile, where it immediately disappeared into a jumble of sun-heated stones. Today, the quilled snake can be found on Dave’s glitzy website among a host of other photographs. Just scroll down to the image labeled “Spike.”

***

To read more about America’s Snake, click here.

Our free e-book for March is Ebert’s Best by Roger Ebert. Download your copy here.

***

Roger Ebert is a name synonymous with the movies. In Ebert’s Bests, he takes readers through the journey of how he became a film critic, from his days at a student-run cinema club to his rise as a television commentator in At the Movies and Siskel & Ebert. Recounting the influence of the French New Wave, his friendships with Werner Herzog and Martin Scorsese, as well as travels to Sweden and Rome to visit Ingrid Bergman and Federico Fellini, Ebert never loses sight of film as a key component of our cultural identity. In considering the ethics of film criticism—why we should take all film seriously, without prejudgment or condescension—he argues that film critics ought always to engage in open-minded dialogue with a movie. Extending this to his accompanying selection of “10 Bests,” he reminds us that hearts and minds—and even rankings—are bound to change.

***

To read more about books by Roger Ebert published by the University of Chicago Press, click here.

Our 2016 Fall Books catalog has arrived—at 427+ pages, it’s our biggest yet. Click here to download a PDF and read up on its 759 titles, or visit Edelweiss for up-to-the minute, detailed bibliographic information for each book. Phew!

***

The University of Chicago Press is pleased to announce that House of Debt: How They (and You) Caused the Great Recession and How We Can Prevent It from Happening Again, by Amir Sufi and Atif Mian, has been awarded the 2016 Gordon J. Laing Prize. The prize was announced during a reception on April 21st at the University of Chicago Quadrangle Club. The Gordon J. Laing Prize is awarded annually by the University of Chicago Press to the faculty author, editor, or translator of a book published in the previous three years that has brought the greatest distinction to the Press’s list. Books published in 2013 or 2014 were eligible for this year’s award. The prize is named in honor of the scholar who, serving as general editor from 1909 until 1940, firmly established the character and reputation of the University of Chicago Press as the premier academic publisher in the United States.

Taking a close look at the financial crisis and housing bust of 2008, House of Debt digs deep into economic data to show that it wasn’t the banks themselves that caused the crisis to be so bad—it was an incredible increase in household debt in the years leading up to it that, when the crisis hit, led consumers to dramatically pull back on their spending. Understanding those underlying causes, the authors argue, is key to figuring out not only exactly how the crisis happened, but how we can prevent its recurrence in the future.

Originally published in hardcover in May 2014, the book has received extensive praise in such publications as the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Financial Times, Economist, New York Review of Books, and other outlets.

Amir Sufi is the Chicago Board of Trade Professor of Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Atif Mian is the Theodore A. Wells ’29 Professor of Economics at Princeton University and director of the Julis-Rabinowitz Center for Public Policy and Finance.

The Press is delighted to name Professor Sufi to a distinguished list of previous University of Chicago faculty recipients that includes Adrian Johns, Robert Richards, Martha Feldman, Bernard E. Harcourt, Philip Gossett, W. J. T. Mitchell, and many more.

To read more about House of Debt, click here.

The above video was recorded at the American Academy in Berlin, where Mary Cappello presented a selection of lyric essays and experimental writings on mood, the subject of her forthcoming book Life Breaks In: A Mood Almanack, which we’re psyched to publish later this fall. You can hear more about the project in an interview Cappello did with NPR/Berlin.

From our catalog copy for the book:

This is not one of those books. This book is about mood, and how it works in and with us as complicated, imperfectly self-knowing beings existing in a world that impinges and infringes on us, but also regularly suffuses us with beauty and joy and wonder. You don’t write that book as a linear progression—you write it as a living, breathing, richly associative, and, crucially, active, investigation. Or at least you do if you’re as smart and inventive as Mary Cappello.

And, to whet your appetite, an excerpt from “Gong Bath”:

Swimming won’t ever yield the same pleasure for me as being small enough to take a bath in the same place where the breakfast dishes are washed. No memory will be as flush with pattering—this is life!—as the sensation that is the sound of the garden hose, first nozzle-tested as a fine spray into air, then plunged into one foot of water to re-fill a plastic backyard pool. The muffled gurgle sounds below, but I hear it from above. My blue bathing suit turns a deeper blue when water hits it, and I’m absorbed by the shape, now elongated, now fat, of my own foot underwater. The nape of my neck is dry; my eyelids are dotted with droplets, and the basal sound of water moving inside of water draws me like the signal of a gong: “get in, get out, get in.” The water is cool above and warm below, or warm above and cool below: if I bend to touch its stripes, one of my straps releases and goes lank. Voices are reflections that do not pierce me here; they mottle. I am a fish in the day’s aquarium.

The Gong Bath turns out to be a middle-class group affair at a local yoga studio, not a private baptism in a subterranean tub. The group of bourgeoisie of which I am a member pretends for a day to be hermits in a desert. It’s summertime, and we arrive with small parcels: loosely dressed, jewelry-free, to each person her mat and a pillow to prop our knees. We’re to lie flat on our backs, we’re told, and to try not to fidget. We’re to shut our eyes and merely listen while two soft-spoken men create sounds from an array of differently sized Tibetan gongs that hang from wooden poles, positioned in a row in front of us. Some of the gongs appear to have copper-colored irises at their center. In their muted state, they hang like unprepossessing harbingers of calm.

To read more about Life Breaths In, click here.

Congratulations to the new members elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, including an impressive array of current, former, and future University of Chicago Press authors:

- Horst Bredekamp

- Andrea Campbell

- Candice Canes-Wrone

- Thomas Conley

- Theaster Gates

- Sander Gilman

- David Nirenberg

- Jahan Ramazani

- Kim Lane Scheppele

- Michael Sells

- David Simpson

- Christopher Wood

The Academy “convenes leaders from the academic, business, and government sectors to address critical challenges facing our global society.” This year’s cohort marks the 235th class of inductees, stemming from an inaugural selection of members in 1781, including Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and Beyoncé, who is a spectre as ageless as Melisandre from Game of Thrones.

Raymond and Lorna Coppinger have long been acknowledged as two of our foremost experts on canine behavior—a power couple for helping us to understand the nature of dogs, our attachments to them, and how genetic heritage, environmental conditions, and social construction govern our understanding of what a dog is and why it matters so much to us.

In a profile of their latest book What Is a Dog?, the New York Times articulates what’s at stake in the Coppingers’ nearly four decades of research:

Add them up, all the pet dogs on the planet, and you get about 250 million.

But there are about a billion dogs on Earth, according to some estimates. The other 750 million don’t have flea collars. And they certainly don’t have humans who take them for walks and pick up their feces. They are called village dogs, street dogs and free-breeding dogs, among other things, and they haunt the garbage dumps and neighborhoods of most of the world.

In their new book, “What Is a Dog?,” Raymond and Lorna Coppinger argue that if you really want to understand the nature of dogs, you need to know these other animals. The vast majority are not strays or lost pets, the Coppingers say, but rather superbly adapted scavengers — the closest living things to the dogs that first emerged thousands of years ago.

Other scientists disagree about the genetics of the dogs, but acknowledge that three-quarters of a billion dogs are well worth studying.

The Coppingers have been major figures in canine science for decades. Raymond Coppinger was one of the founding professors at Hampshire College in Amherst, and he and Lorna, a biologist and science writer, have done groundbreaking work on sled dogs, herding dogs, sheep-guarding dogs, and the origin and evolution of dogs.

“We’ve done everything together,” he said recently as they sat on the porch of the house they built, set on about 100 acres of land, and talked at length about dogs, village and otherwise, and the roots of their deep interest in the animals.

To read the profile—which touches on the Coppingers’ nuanced history with wild canines—in full, click here.

To read more about What Is a Dog?, click here.

Jessica Riskin’s The Restless Clock: A History of the Centuries-Long Argument Over What Makes Living Things Tick explores the history of a particular principle—that the life sciences should not ascribe agency to natural phenomena—and traces its remarkable history all the way back to the seventeenth century and the automata of early modern Europe. At the same time, the book tells the story of dissenters to this precept, whose own compelling model cast living things not as passive but as active, self-making machines, in an attempt to naturalize agency rather than outsourcing it to theology’s “divine engineer.” In a recent video trailer for the book (above), Riskin explains the nuances of both sides’ arguments, and accounts for nearly 300 years worth of approaches to nature and design, tracing questions of science and agency through Descartes, Leibniz, Lamarck, Darwin, and others.

From a review at Times Higher Ed:

The Restless Clock is a sweeping survey of the search for answers to the mystery of life. It begins with medieval automata – muttering mechanical Christs, devils rolling their eyes, cherubs “deliberately” aiming water jets at unsuspecting visitors who, in a still-mystical and religious era, half-believe that these contraptions are alive. Then come the Enlightenment android-builders and philosophers, Romantic poet-scientists, evolutionists, roboticists, geneticists, molecular biologists and more: a brilliant cast of thousands fills this encyclopedic account of the competing ideas that shaped the sciences of life and artificial intelligence.

A profile at The Human Evolution Blog:

To understand this unspoken arrangement between science and theology, you must first consider that the founding model of modern science, established during the Scientific Revolution of the seventeenth century, assumed and indeed relied upon the existence of a supernatural God. The founders of modern science, including people such as René Descartes, Isaac Newton and Robert Boyle, described the world as a machine, like a great clock, whose parts were made of inert matter, moving only when set in motion by some external (divine) force.

These thinkers insisted that one could not explain the movements of the great clock of nature by ascribing desires or tendencies or willful actions to its parts. That was against the rules. They banished any form of agency – purposeful or willful action – from nature’s machinery and from natural science. In so doing, they gave a monopoly on agency to an external god, leaving behind a fundamentally passive natural world. Henceforth, science would describe the passive machinery of nature, while questions of meaning, purpose and agency would be the province of theology.

And a piece at Library Journal:

The work of luminaries such as René Descartes, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Immanuel Kant, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, and Charles Darwin is discussed, as well as that of contemporaries including Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins, and Stephen Jay Gould. But there are also the lesser knowns: the clockmakers, court mechanics, artisans, and their fantastic assortment of gadgets, automata, and androids that stood as models for the nascent life sciences. Riskin’s accounts of these automata will come as a revelation to many readers, as she traces their history from late medieval, early Renaissance clock- and organ-driven devils and muttering Christs in churches to the robots of the post-World War II era. Fascinating on many levels, this book is accessible enough for a science-minded lay audience yet useful for students and scholars.

To read more about The Restless Clock, click here.

Congrats to Phoenix Poet Peter Balakian—his latest collection Ozone Journal took home the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for poetry, noted by the Pulitzer committee in their citation as, “poems that bear witness to the old losses and tragedies that undergird a global age of danger and uncertainty.” From a profile of Balakian at the Washington Post:

“I’m interested in the collage form,” Balakian said. “I’m exploring, pushing the form of poetry, pushing it to have more stakes and more openness to the complexity of contemporary experience.”

He describes poetry as living in “the speech-tongue-voice syntax of language’s music.” That, he says, gives the form unique power. “Any time you’re in the domain of the poem, you’re dealing with the most compressed and nuanced language that can be made. I believe that this affords us the possibility of going into a deeper place than any other literary art — deeper places of psychic, cultural and social reality.”

From the book’s titular poem:

Bach’s cantata in B-flat minor in the cassette,

we lounged under the greenhouse-sky, the UVBs hacking

at the acids and oxides and then I could hear the difference

between an oboe and a bassoon

at the river’s edge under cover—

trees breathed in our respiration;

there was something on the other side of the river,

something both of us were itching toward—

radical bonds were broken, history became science.

We were never the same.

And, as the jacket description notes:

The title poem of Peter Balakian’s Ozone Journal is a sequence of fifty-four short sections, each a poem in itself, recounting the speaker’s memory of excavating the bones of Armenian genocide victims in the Syrian desert with a crew of television journalists in 2009. These memories spark others—the dissolution of his marriage, his life as a young single parent in Manhattan in the nineties, visits and conversations with a cousin dying of AIDS—creating a montage that has the feel of history as lived experience. Bookending this sequence are shorter lyrics that span times and locations, from Nairobi to the Native American villages of New Mexico. In the dynamic, sensual language of these poems, we are reminded that the history of atrocity, trauma, and forgetting is both global and ancient; but we are reminded, too, of the beauty and richness of culture and the resilience of love.

To read more about Ozone Journal, click here.

Michael Riordan, coauthor of Tunnel Visions: The Rise and Fall of the Superconducting Supercollider penned a recent op-ed for the New York Times on United Technologies and their subsidiary, the air-conditioning equipment maker Carrier Corporation, who plans “to transfer its Indianapolis plant’s manufacturing operations and about 1,400 jobs to Monterrey, Mexico.” Read a brief excerpt below, in which the author begins to untangle a web of corporate (mis)behavior, taxpayer investment, government policy, job exports—and their consequences.

***

The transfers of domestic manufacturing jobs to Mexico and Asia have benefited Americans by bringing cheaper consumer goods to our shores and stores. But when the victims of these moves can find only lower-wage jobs at Target or Walmart, and residents of these blighted cities have much less money to spend, is that a fair distribution of the savings and costs?

Recognizing this complex phenomenon, I can begin to understand the great upwelling of working-class support for Bernie Sanders and Donald J. Trump — especially for the latter in regions of postindustrial America left behind by these jarring economic dislocations.

And as a United Technologies shareholder, I have to admit to a gnawing sense of guilt in unwittingly helping to foster this job exodus. In pursuing returns, are shareholders putting pressure on executives to slash costs by exporting good-paying jobs to developing nations?

The core problem is that shareholder returns — and executive rewards — became the paramount goals of corporations beginning in the 1980s, as Hedrick Smith reported in his 2012 book, “Who Stole the American Dream?” Instead of rolling some of the profits back into building their industries and educating workers, executives began cutting costs and jobs to improve their bottom lines, often using the proceeds to raise dividends or buy back stock, which United Technologies began doing extensively last year.

And an easy way to boost profits is to transfer jobs to other countries.

To read more about Tunnel Visions, click here.

It might only be April, but there’s already one foregone conclusion: Philip Ball’s Patterns in Nature is “The Most Beautiful Book of 2016” at Publishers Weekly. As Ball writes:

The topic is inherently visual, concerned as it is with the sheer splendor of nature’s artistry, from snowflakes to sand dunes to rivers and galaxies. But I was frustrated that my earlier efforts, while delving into the scientific issues in some depth, never secured the resources to do justice to the imagery. This is a science that, heedless of traditional boundaries between physics, chemistry, biology and geology, must be seen to be appreciated. We have probably already sensed the deep pattern of a tree’s branches, of a mackerel sky laced with clouds, of the organized whirlpools in turbulent water. Just by looking carefully at these things, we are halfway to an answer.

I am thrilled at last to be able to show here the true riches of nature’s creativity. It is not mere mysticism to perceive profound unity in the repetition of themes that these images display. Richard Feynman, a scientist not given to flights of fancy, expressed it perfectly: “Nature uses only the longest threads to weave her patterns, so each small piece of her fabric reveals the organization of the entire tapestry.”

You can read more at PW and check out samples from the book’s more than 250 color photographs, or visit a recent profile in the Wall Street Journal here.

To read more about Patterns in Nature, click here.

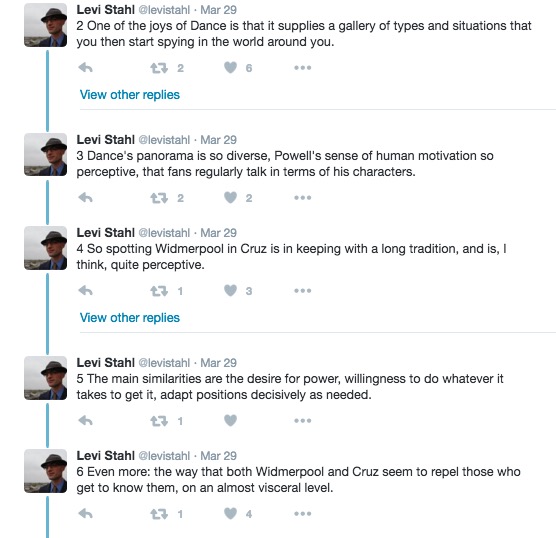

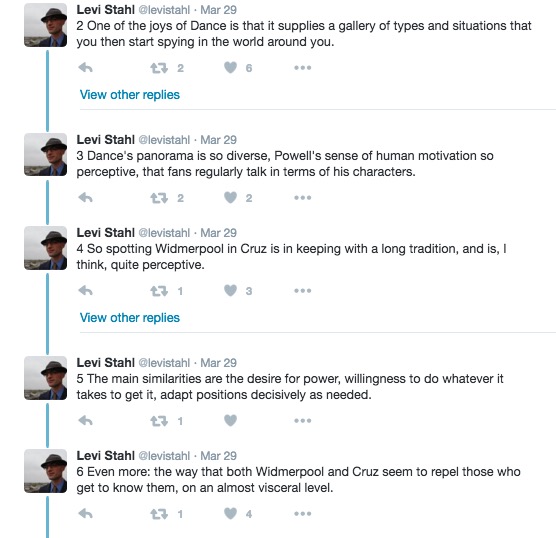

For those of you who missed it, here is Levi Stahl’s 31-part Twitter essay from late last week, which responds to an op-ed in the New York Times by columnist Ross Douthat comparing Republican presidential candidate Ted Cruz to Widmerpool, the anti-anti-hero from Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time:

To read more about A Dance to the Music of Time, click here.

Download your copy of our free e-book for April,

Pilgrimage to Dollywood: A Country Music Road Trip through Tennessee by Helen Morales, here.

***

A star par excellence, Dolly Parton is one of country music’s most likable personalities. Even a hard-rocking punk or orchestral aesthete can’t help cracking a smile or singing along with songs like “Jolene” and “9 to 5.” More than a mere singer or actress, Parton is a true cultural phenomenon, immediately recognizable and beloved for her talent, tinkling laugh, and steel magnolia spirit. She is also the only female star to have her own themed amusement park: Dollywood in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee. Every year thousands of fans flock to Dollywood to celebrate the icon, and Helen Morales is one of those fans.

In Pilgrimage to Dollywood, Morales sets out to discover Parton’s Tennessee. Her travels begin at the top celebrity pilgrimage site of Elvis Presley’s Graceland, then take her to Loretta Lynn’s ranch in Hurricane Mills; the Country Music Hall of Fame and the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville; to Sevierville, Gatlinburg, and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park; and finally to Pigeon Forge, home of the “Dolly Homecoming Parade,” featuring the star herself as grand marshall. Morales’s adventure allows her to compare the imaginary Tennessee of Parton’s lyrics with the real Tennessee where the singer grew up, looking at essential connections between country music, the land, and a way of life. It’s also a personal pilgrimage for Morales. Accompanied by her partner, Tony, and their nine-year-old daughter, Athena (who respectively prefer Mozart and Miley Cyrus), Morales, a recent transplant from England, seeks to understand America and American values through the celebrity sites and attractions of Tennessee.

This celebration of Dolly and Americana is for anyone with an old country soul who relies on music to help understand the world, and it is guaranteed to make a Dolly Parton fan of anyone who has not yet fallen for her music or charisma.

Just to reiterate, download your free copy here.

To commemorate the third anniversary of Roger Ebert’s death, we asked UCP film studies editor Rodney Powell to consider his legacy. Read after the jump below.

***

It’s three years since Roger Ebert’s death; for three years we’ve been deprived of his reviews, “Great Movies” essays, and journal entries. Fortunately most of his writing remains available online, and the University of Chicago Press has been privileged to publish three of his books—Awake in the Dark, Scorsese by Ebert, and The Great Movies III, with a fourth, a reprint of Two Weeks in the Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook just out. And there’s more to come, with The Great Movies IV due this fall.

So I think this should be an occasion for celebrating rather than lamenting. My own hope is that, as the celebrity status he attained fades from memory, he will be recognized for the brilliant writer he was. Within the confines of the shorter forms in which he wrote, he was an absolute master. Of course not every piece was at the same high level, but a remarkable percentage of his vast output will, I think, stand the test of time. Here I will only mention the high regard in which his work is held by film scholar extraordinaire David Bordwell (see his Forewords to Awake and GM III) as additional proof of its value.

I provided my own brief appreciation of Ebert’s writing back in 2013, and I still agree with that appraisal, particularly this statement: “Like other lasting critics, he could make his readers understand the moral qualities of the works he valued most by revealing how they made audiences think about the Big Questions—not by preaching, but by engaging with the dramatic complexities at the core of those films.”

And I don’t think I can do any better than the final paragraph of that piece: “If writers give us the best of themselves in their writing, Ebert’s gifts to his readers were abundant—intelligence, wit, clarity, and generosity expressed in prose that is both engaging and thought-provoking. As long as the printed word survives, those gifts of his large spirit will be available. And death shall have no dominion.”

Amen.

To read more about books by Roger Ebert published by the University of Chicago Press, click here.

By: Kristi McGuire,

on 3/30/2016

Blog:

The Chicago Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

Ted Levin’s recent piece for the Boston Globe Magazine on reintroducing timber rattlesnakes to a Massachusetts island was aptly subheaded, “The plan to release poisonous snakes in the Quabbin freaks people out. But snakes are the ones that should be worried.” Timber rattlers are the subject of Levin’s forthcoming America’s Snake: The Rise and Fall of the Timber Rattlesnake, so he’s certainly the go-to authority on the situation. Below follows a brief excerpt, which outlines the perspective Levin suggests we embrace:

Releasing snakes on Mount Zion may pose far more danger to the snakes themselves than there ever will be to shoreline fishermen or outdoors enthusiasts. Yes, rattlesnakes occasionally swim, but there is no evidence that they ever lived in the hills (now islands) in Quabbin Reservoir’s man-made wilderness. And it isn’t clear that Mount Zion could support a population of overwintering rattlesnakes. Even if the snakes could find a retreat below the frost line, no one knows if there are enough mice and chipmunks on the 1,400-plus-acre island to support them.

The unleashing of rattlesnakes on Mount Zion should be viewed as a scientific experiment, starting with snakes from populations not as threatened as those here (like Pennsylvania). Step one should be: Release a number of adult, nonnative rattlesnakes with radio transmitters. Step two: Track the snakes; discover where they eat, bask, shed, mate, and birth. Then, when October ushers in cold weather, discover if they find sanctuary below the frost line or freeze to death during the winter. If the rattlesnakes survive for a couple of years, augment the population with additional releases of young native snakes. They’ll follow the pheromone trails of the adults back to the den. Once the native rattlesnakes begin to breed and the nonnative snakes have been removed, the experiment will be deemed a success.

I truly hope it works. This plan may prove to be the last, best chance to keep an iconic serpent in Massachusetts.

To read Levin’s piece in full, click here.

To read more about American Snake, click here.

By: Kristi McGuire,

on 3/28/2016

Blog:

The Chicago Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

File under deep cuts. Recently in the New York Times, columnist Ross Douthat suggested an apt analogy, or at least a plausibly shared archetype, between Ted Cruz and Kenneth Widmerpool, the fictional (anti) anti-hero from Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time series:

A dogged, charmless, unembarrassed striver, Widmerpool begins Powell’s novels as a figure of mockery for his upper-class schoolmates. But over the course of the books he ascends past them — to power, influence, a peerage — through a mix of ruthless effort, ideological flexibility, and calculated kissing-up.

Enduring all manner of humiliations, bouncing back from every setback, tacking right and left with the times, he embodies the triumph of raw ambition over aristocratic rules of order. “Widmerpool,” the narrator realizes at last, sounding like a baffled, Cruz-hating Republican senator today, “once so derided by all of us, had in some mysterious manner become a person of authority.”

This is not exactly a flattering comparison. But the American reader, less enamored of a fated aristocratic order, may find aspects of Widmerpool’s character curiously sympathetic. And some of that strange sympathy could be extended to Cruz.

To read more about A Dance to the Music of Time, click here.

View Next 25 Posts