new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: The New Yorker, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 60

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: The New Yorker in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Generalized definitions of anything—or anyone—are provocative, sure. They get the readers' ire up. Which is to say they attract more readers. I am sure that Anthony Lane of

The New Yorker (a terrific if mostly acerbic reviewer) knows that YA fiction comes in many hues and forms and flavors, and that it is fed by many ideals and many wild imaginations, many time periods, many themes, and a full array of characters and landscapes.

But here, in Lane's review of the movie "If I Stay," based on the Gayle Forman novel, he issues a standardizing decree.

Young-adult fiction: what a peculiar product it is, sold and consumed as avidly as the misery memoir and the self-help book, and borrowing sneakily from both. One can see the gap in the market. What are literate kids meant to do with themselves, or with their itchy brains, as they wander the no man's land between Narnia and Philip Roth? The ideal protagonist of the genre is at once victimized and possessed of decisive power—someone like Mia, the heroine of Gayle Forman's "If I Stay," which has clung grimly to the Times best-seller list, on and off, for twenty weeks. And the ideal subject is death, or, as we should probably call it, the big sleepover.

Oh, the blogs/articles/talks that will erupt from this. Oh. Or? Perhaps we who write young adult fiction that is not part misery memoir and not self-help book, not, indeed, any single one thing, grow weary of the castigating, the easy sarcasm, the sneak and overt attacks?

Let others stomp their feet and say what they will. We've got work to do.

In November 2009, Ariel Levy, a New Yorker writer, wrote

an essay about the runner Caster Semenya ("Either/Or"). She was South African, a world champion, a "natural." She had a body built for speed, a body, Levy tells us, that got some whispers started:

Semenya is breathtakingly butch. Her torso is like the chest plate on a suit of armor. She has a strong jawline, and a build that slides straight from her ribs to her hips. “What I knew is that wherever we go, whenever she made her first appearance, people were somehow gossiping, saying, ‘No, no, she is not a girl,’ ” Phineas Sako said, rubbing the gray stubble on his chin. “ ‘It looks like a boy’—that’s the right words—they used to say, ‘It looks like a boy.’ Some even asked me as a coach, and I would confirm: it’s a girl. At times, she’d get upset. But, eventually, she was just used to such things.” Semenya became accustomed to visiting the bathroom with a member of a competing team so that they could look at her private parts and then get on with the race. “They are doubting me,” she would explain to her coaches, as she headed off the field toward the lavatory.

I remember reading this story front to back the day that issue of

The New Yorker arrived. I felt compassion—that's what I felt—for a young athlete who was working hard and running fast and doubted. For a human being who'd had nothing to say about the nature of the body she'd been born with, who was living out the dream she had, who was being dogged and thwarted by questions. Caster Semenya was a runner. She had committed no crime. And yet there was her story—in headlines, in gossip. What were her choices, after all?

Later this year, I.W. Gregorio, a beloved physician, a former student of one of my dearest friends (Karen Rile), a joyous presence at many book launches and festivals, and a leading voice in the We Need Diverse Books initiative that has packed rooms at the BEA and the LA SCBWI, will launch a book called NONE OF THE ABOVE. This YA novel is about a high school runner—a beautiful girl with a boyfriend, a popular teen—who finds herself having this conversation with the physician who has examined her:

-->

"So, Kristin," Dr. Shah said, "In that ultrasound I just did I wasn't able to find your uterus – your womb – at all."

"What do you mean?" I stared at her blankly.

"I want you to think back to all your visits to doctors in the past. Did anyone ever mention anything to you about something called Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome, or AIS?"

"No," I said, panic rising. "What is that? It's not some kind of cancer, is it?"

"Oh, no," Dr. Shah said. "It's not anything like that. It's just a...a unique genetic syndrome that causes an intersex state - where a person looks outwardly like a female, but has some of the internal characteristics of a male."

"What do you mean, internal? Like my brain?" My chest tightened. What else could it be?

Dr. Shah's mouth opened, but then she paused, as if she wasn't sure whether she should go on. I was still trying to understand what she'd said, so I focused on her mouth as if that would allow me to understand better. I noticed that her lip-liner was a shade too dark for her lipstick. "Kristin. Miss Lattimer," she said. Why was she being so formal all the sudden?

"I think that you may be..." Dr. Shah stopped again and fingered nervously at the lanyard of her ID badge, and at her awkwardness I felt a sudden surge of sympathy toward her. So I swallowed and put on my listening face, and was smiling when Dr. Shah gathered herself and, on the third try, said what she had to say.

"Miss Lattimer, I think that you might be what some people call a 'hermaphrodite.'"

What do the words mean? What does the diagnosis tell Kristin about who she really is? How will it change her life, what medical choices does she have, who will love the "who" of her? These are the questions Gregorio sensitively and compellingly addresses as this story unfolds—bit by bit, choice by choice, reckoning by reckoning. It takes a physician of Gregorio's knowledge and skill to tell this story. It takes, as well, a compassionate heart, and Ilene has that in spades. Ilene has not written this story to exploit. She has written it so that others might understand a condition that is more common than we think, a dilemma many young people and their parents face.

We Need More Diverse Books, and

None of the Above is one of them. I share my blurb for Gregorio's book here, and wish her greatest success as her story moves into the world.

Like the beloved physician she is, I.W Gregorio brings rare knowledge and acute empathy to the illumination of an anatomical difference—and to the teens who discover, in the nick of time, the saving grace of knowing and being one’s truest self. A book unlike any other.

— Beth Kephart, author of Going Over and Small Damages

Today we look at the work of Celyn Brazier, Cartoon Brew's Artist of the Day!

This week's issue of "The New Yorker" does something that they rarely ever do: review an animated TV series. The show they elected to discuss is "Adventure Time."

The other day, while waiting an hour or so down the road for a friend to arrive for a long-planned lunch date, I stole a few minutes with the February 25 issue of

The New Yorker, which I had slipped into my oversized bag.

The magazine fell to page 77, Joan Acocella's story on Adam Phillips, called "This is Your Life." This first paragraph needs no Kephart intercessions. Just read it, and see if, on this day at least, it might save you. The photo above, by the way, is of Jeb Stuart Wood, whom

I profiled in the Inquirer on Sunday. He's a foundry man at work here on a piece for the great sculptress Michele Oka Doner. Behind him are the old mobiles he restores when he finds time. Elsewhere are his own sculptures, suspended and waiting. I thought of Jeb often after my interview that day—of how broadly and peaceably he was

living. From

The New Yorker:

Adam Phillips, Britain's foremost psychoanalytic writer, dislikes the modern notion that we should all be out there fulfilling our potential, and this is the subject of his new book, "Missing Out: In Praise of the Unlived Life (Farrar, Straus & Giroux). Instead of feeling that we should have a better life, he says, we should just live, as gratifyingly as possible, the life we have. Otherwise, we are setting ourselves up for bitterness. What makes us think we could have been a contender? Yet, in the dark of the night, we do think this, and grieve that it isn't possible. "And what was not possible all too easily becomes the story of our lives," Phillips writes. "Our lived lives might become a protracted mourning for, or an endless trauma about, the lives we were unable to live."

Larissa MacFarquhar writes pieces for

The New Yorker that anyone seriously engaged with literature must read. This is the case again with her October 15 profile of Hilary Mantel, author of

Wolf Hall, which begins with these reflections on the writing of historical fiction. I share the opening, urging you to find the magazine and read the essential whole.

What sort of person writes fiction about the past? It is helpful to be acquainted with violence, because the past is violent. It is necessary to know that the people who live there are not the same people now. It is necessary to understand that the dead are real, and have power over the living. It is helpful to have encountered the dead firsthand, in the form of ghosts.

The writer's relationship with a historical character is in some was less intimate than with a fictional one: the historical character is elusive and far away, so there is more distance between them. But there is also more equality between them, and more longing; when he dies, real mourning is possible.

Historical fiction is a hybrid form, halfway between fiction and nonfiction. It is a pioneer country, without fixed laws.....

On another topic altogether, I'll be posting some of the questions and answers from yesterday's Push to Publish YA panel on this blog later today. (I promise.)

Can you spot the two dots in this Mick Stevens cartoon that threaten the New Yorker from being banned from Facebook?

(via Nipplegate: Why the New Yorker Cartoon Department Is About to Be Banned from Facebook : The New Yorker)

By:

Beth Kephart ,

on 7/28/2012

Blog:

Beth Kephart Books

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Alyson Hagy,

David Remnick,

April Lindner,

Robb Forman Dew,

Rosella Eleanor LaFevre,

Jessica Springsteen,

Jessica Ferro,

Ned Balbo,

Tamara Smith,

Ann Michael,

Bruce Springsteen,

The New Yorker,

Jane Satterfield,

Add a tag

Could there be anything more thrilling (for a reader-rocker) than reading the beautifully researched, impeccably written David Remnick profile of Bruce Springsteen in the July 30 issue of

The New Yorker? The story is called "We Are Alive," and most everyone read it before I did, because my issue didn't arrive until late yesterday afternoon. I'd read pieces online. I'd read the raves. But yesterday, after a very long day of corporate work and minor agitations, I found a breeze and read the profile through. I didn't have to fall in love again with Bruce Springsteen; I've been in love since I was a kid. But I loved, loved, loved every word of this story. I would like to frame it.

(For those who haven't seen my Devon Horse Show photos and video of Jessica Springsteen, who is as sensational in her way as Bruce is, I share them

here.)

Perhaps my favorite part of Remnick's article was discovering the way that Springsteen reads, how he thinks about books. You don't get to be sixty-two and still magnetic, necessary, pulsingly, yes, alive if you don't know something, and if you don't commit yourself to endless learning. Reading is one of the many ways Springsteen stays so connected to us, and so relevant. From

The New Yorker:Lately, he has been consumed with Russian fiction. "It's compensatory—what you missed the first time around," he said. "I'm sixty-some, and I think, There are a lot of these Russian guys! What's all the fuss about? So I was just curious. That was an incredible book: 'The Brothers Karamazov.' Then I read 'The Gambler.' The social play in the first half was less interesting to me, but the second half, about obsession, was fun. That could speak to me. I was a big John Cheever fan, and so when I got into Chekhov I could see where Cheever was coming from. And I was a big Philip Roth fan, so I got into Saul Bellow, 'Augie March.' These are all new connections for me. It'd be like finding out now that the Stones covered Chuck Berry."

Next week, I'll begin to write my paper for

Glory Days: The Bruce Springsteen Symposium, which is being held in mid-September at Monmouth University, and where I'll be joining April Lindner, Ann Michael, Jane Satterfield, and Ned Balbo on a panel called "Sitting Round Here Trying to Write This Book: Bruce Springsteen and Literary Inspiration." I don't know if I've ever been so intimidated, or (at the same time) excited. I don't know what I have in me, if I can write smart and well enough.

But this morning I take my energy, my inspiration, from the friends and good souls who have written over the past few days to tell me about their experience with

Small Damages. We writers write a long time, and sometimes our work resonates, and when it does, we are so grateful. When others reach out to us, we don't know what to say. We hope that thank you is enough. And so, this morning, thank you, Alyson Hagy and Robb Forman Dew. Thank you, Tamara Smith. Thank you, Elizabeth Ator and Katherine Wilson. Thank you, Jessica Ferro. Thank you, Hilary Hanes. And thank you, Miss Rosella Eleanor LaFevre, who interviewed me a few years ago about

Dangerous Neighbors, and who has stayed in touch ever since. I don't even know how to say thank you for

3 Comments on Bruce Springsteen, Glory Days Symposium, and Thanks, last added: 7/30/2012

Comedian and author Andy Borowitz revealed today that The New Yorker has acquired his blog, The Borowitz Report. Starting today, readers will find his satirical pieces at the magazine’s website.

Comedian and author Andy Borowitz revealed today that The New Yorker has acquired his blog, The Borowitz Report. Starting today, readers will find his satirical pieces at the magazine’s website.

Borowitz joked that editor David Remnick will allow the humorist to write for the magazine as long as “I don’t make fun of Malcolm Gladwell.”

The announcement ended with a serious dedication to the writer’s mother. Here’s more: “if you’ll forgive me, I’d like to say one last thing that’s true. My mom, Helen Borowitz, who died this month at the age of eighty-three, loved The New Yorker all her life and introduced me to it when I was a little boy. Seeing the Borowitz Report at The New Yorker would have made her so happy. I dedicate all my columns to her memory.”

continued…

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

If you still haven’t had your fill of “Why John Carter Failed” articles, then don’t miss New York Magazine’s lengthy read “The Inside Story of How John Carter Was Doomed by Its First Trailer.” The piece goes to excruciating lengths to absolve Disney marketing of any wrongdoing over the film’s US box office performance, and lays the blame squarely at the feet of Andrew Stanton:

While this kind of implosion usually ends in a director simmering in rage at the studio marketing department that doomed his or her movie, Vulture has learned that it was in fact John Carter director Andrew Stanton — powerful enough from his Pixar hits that he could demand creative control over trailers — who commandeered the early campaign, overriding the Disney marketing execs who begged him to go in a different direction.

The article, juicy as it is, should be taken with a grain of salt. Much of the information in the article appears to be sourced from public statements by Stanton, and only one anonymous “Disney marketing insider” is identified as having been interviewed. There are factual errors too that made me question the piece’s accuracy—the writer claims that Disney marketing approached the New Yorker in September 2011 to profile Stanton, when in fact, if you read the New Yorker piece, the writer of that piece said he’d been working on it since April 2011. At best, NY Mag’s takedown offers one version of how the film’s marketing plan derailed. The real story is likely far more complex, and won’t be understood until some point in the future.

A more insightful piece is the aforementioned New Yorker profile of Andrew Stanton, which has finally been posted online. Unlike an earlier New Yorker piece about Pixar that left me unimpressed, this profile sheds much light on Stanton’s personality and his collaboration with the lauded Pixar “Braintrust.” In spite of the profile’s positive tone, Stanton comes off as overly self assertive and oblivious to the effect of his comments, like:

“We came on this movie so intimidated: ‘Wow, we’re at the adult table!’ Three months in, I said to my producers, ‘Is it just me, or do we actually know how to do this better than live-action crews do?’ The crew were shocked that they couldn’t overwhelm me, but at Pixar I got used to having to think about everyone else’s problems months before all their pieces would come together, and I learned that I’m just better at communicating and distilling than other people.”

(Illustration by Luis Grañena)

Cartoon Brew |

Permalink |

11 comments |

Post tags: Andrew Stanton, John Carter, The New Yorker

I am in the midst of reading a book which many readers before me have termed "beautiful." In places, I would agree—there is a lush knowing, a seductive tumble forward of palpable scenes and words. In other passages, however, the book gets uncomfortably stuck; the characters don't read as real; the dialogue, especially, trembles with information as opposed to charm or persuasion; the teens (and this is an adult novel with a teen hook) are, in my opinion, false constructions—their conversation heavy handed with genericized slang. I read on, but I stop and think. Analyze what works and what doesn't, and (most importantly) why.

I took a break from reading that book to read an October 17

New Yorker piece titled "Sons and Lovers" by James Wood. The essay is ostensibly a review of Alan Hollinghurst's novel,

The Stranger's Child. But because this is James Wood, we're also treated to a lively linguistic lesson by the man who wrote a little book that I hope you writers all have at hand,

How Fiction Works. Love that book. Need it.

In any case, back to the subject at hand, which is the word "beautiful" as it is applied to prose, and what James Wood has to say—with infinite brilliance—about that. Here he is, at the essay's start. Please read the whole. It's worth it.

Most of the prose writers acclaimed for "writing beautifully" do no such thing; such praise is issued comprehensively, like the rain on the just and the unjust. Mostly, what's admired as beautiful is ordinary; or sometimes it's too obviously beautiful, feebly fine—what Nabokov once called "weak blond prose." The English novelist Alan Hollinghurst is one of the few contemporary writers who deserve the adverb. His prose has the power of re-description, whereby we are made to notice something hitherto neglected. Yet, unlike a good deal of modern writing, this re-description is not achieved only by inventing brilliant metaphors, or by flourishing some sparkling detail, or by laying down a line of clever commentary. Instead, Hollinghurst works quietly, like a poet, goading all the words in his sentences—nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs—into a stealthy equality.

I live, as many of you know, this odd cross-over life. A corporate communicator by day. A writer of fiction, memoir, poetry by night. A reader in those sacred hours in between. On rare occasions the many lives meet. A client will tell me about a book she is reading, say, or another will ask if I might bring some poetry to the job—write a script for an animation, write copy for a new brand, bring the sound of a lyric to a talk that must be given, do something different. I am grateful for those clients. Grateful for their trust.

I gravitate toward magazine stories about middle grounds, and I am especially intrigued by tales that tie the corporate to the poetic. That happens in John Colapinto's October 3

New Yorker piece titled "Famous Names." The article takes a look the fascinating world of brand naming—who does it, how it gets it done, what sounds mean, what customers see (and hear).

Tucked into the piece is this little nugget about 1957, the Ford Motor Company, and poet Marianne Moore. Ford was seeking a name for "the first affordable automobile." He turned to many, including Moore. He asked her, according to Colapinto's story, for a name that would "convey, through association or other conjuration, some visceral feeling of elegance, fleetness, advanced features and design."

Moore's responses probably do not bode well for a poet at work in corporate America (perhaps I shouldn't tell clients about my secret second life). Still, I find them dear and quaint, and share them with you here:

Intelligent Bullet

Utopian Turtletop

Bullet Cloisone

Pastelogram

Mongoose Civique

Andante con Moto

Snagged from the Sept. 26, 2011 issue of The New Yorker, by Roz Chast. Coincidentally, Chast became a staff cartoonist to the magazine in 1979, the year I graduated high school. It’s like she’s always been there, and I’m grateful for that; I like her work a lot.

And, oh yeah, by the way . . . buy my book. I don’t care which one.

This one, then, is quick: I speak often of my dear friend Alyson Hagy, whose emails to me are rich, whose books are complex and fearless, whose teaching at the University of Wyoming is impeccable, whose friendship I cherish.

This week, one of Alyson's students, Callan Wink, has a story in

The New Yorker called "Dog Run Moon." It's a keeper. Also a keeper is the

post-pub interview that Wink did with Cressida Leyshon. He is asked about his work within the MFA program at the University of Wyoming. He says, among other things, this:

More than anything else though, coming to Wyoming has benefited me in that I’ve had the good fortune to work with some extremely talented and generous writers, both students and faculty. Brad Watson, Rattawut Lapcharoensap, Alyson Hagy (and too many others to list here) have gone out of their way to give my work careful, serious, readings and I’m extremely grateful for that.

I know of what Wink speaks, when it comes to Alyson (and I've read enough of Brad Watson's work to know how he soars). I am glad that others, reading this interview, will know something of the power that emanates from this highly special Wyoming program.

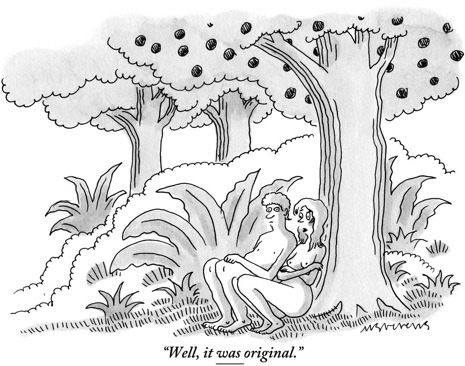

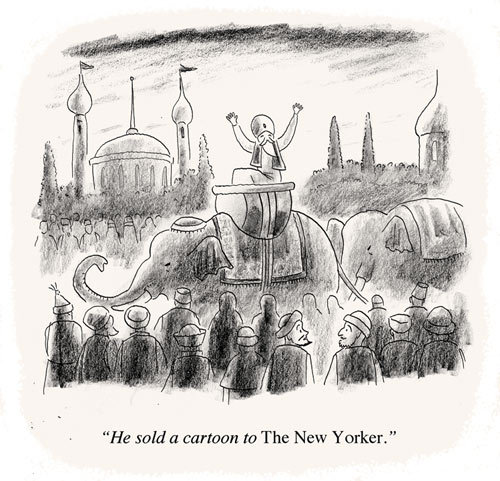

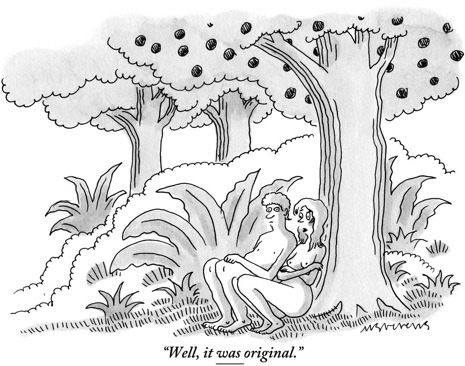

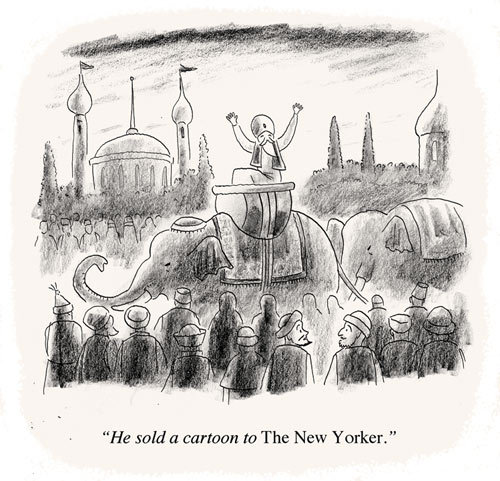

(via How Hard Is It To Get a Cartoon Into The New Yorker? - By James Sturm - Slate Magazine)

James Sturm writes about his experiences drawing and submitting cartoons to the New Yorker.

The New Yorker recently published “The Facebook Sonnet” by Sherman Alexie. The poem follows the AB-AB/CD-CD/EF-EF/GG rhyme scheme of the Shakespearean sonnet.

The New Yorker recently published “The Facebook Sonnet” by Sherman Alexie. The poem follows the AB-AB/CD-CD/EF-EF/GG rhyme scheme of the Shakespearean sonnet.

Here is a couplet from the piece: “Let’s sign up, sign in, and confess / Here at the altar of loneliness.” What do you think?

In the past, Alexie has published several poetry collections including The Business of Fancydancing (1991) and Dangerous Astronomy (2005). He also wrote the illustrated young-adult title, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (2007).

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

Anthony Lane’s fawning eight-page profile of Pixar in the new edition of The New Yorker (May 16) has convinced me that it is next to impossible to write anything of substance about the studio at this time. The studio’s unparalleled string of successes at the box office inevitably leads to writers attempting to figure out why they’ve been so good, and the response from within the studio is always the same tired line about how all the elements of the film are created in the service of the story. That’s a great point, of course, and deserves to be shouted from the rooftops, but it doesn’t exactly make for thought-provoking commentary. Nor does it explain Cars. Lane’s article isn’t on-line, but if you’ve read anything about Pixar in the past few years, then you’ve probably read this piece, too.

Well, actually, Lane does have one original revelation: he harbors a fetish for the, umm, elasticity, of the The Incredibles’ Helen Parr, aka Elastigirl:

Helen, with bendy limbs adaptable for both vacuuming and fistfights, is a living joke about society’s expectation that women should have it all, or do it all, and never take a break. There is, of course, another skill that she could master with her natural sinuosity, but that is never mentioned. Back in 2004, some of us in the movie theatre wanted to shout, “Bob, she’s wearing a black mask and thigh-highs. What are you waiting for, man?” For the sake of the kids, though, we kept quiet. Bedrooms, in Pixar, are places where you chat to monsters, or horse around with your toys: not perspiring rumpus rooms, where Mr. and Mrs. Incredible play adults-only Twister.

Such is the state of commentary about Pixar today.

Cartoon Brew: Leading the Animation Conversation |

Permalink |

One comment |

Post tags: Anthony Lane, The New Yorker

This is not my yard. This is the perfect lawn of Chanticleer Gardens, where two of my books take place and many of my other books have been considered. This is the lawn children tumble down, the lawn my own Chanticleer students once traversed as they made their way from prose poems to villanelles.

This is also not my life—this quiet, green perfection. My life is more like last night—those 45 minutes of sleep that I finally got—or more like this morning, when, after deciding that further sleep was not an option, I turned on my computer only to experience a three-hour computer crash. My email files have now been restored, thank you very much. But it's 11:20 AM, and I have not dressed for the day.

What I have done, while wading through no sleep and no connectivity is to read and blurb a book, to talk to my father, and to read Jonathan Franzen's essay, "Farther Away," in last week's

The New Yorker. This is the piece my dear student brought to me on Tuesday. This is the quality of work she finds inspiring. And no wonder. I share with you now the passage my student read aloud to me, on that gray day, in that dark and too-cold room, her voice the warmth, her presence the light. It's Franzen reflecting on David Foster Wallace:

People who had never read his fiction, or had never even heard of him, read his Kenyon College commencement address in the Wall Street Journal and mourned the loss of a great and gentle soul. A literary establishment that had never so much as short-listed one of his books for a national prize now united to declare him a lost national treasure. Of course, he was a national treasure, and, being a writer, he didn't "belong" to his readers any less than to me. But if you happened to know that his actual character was more complex and dubious than he was getting credit for, and if you also knew that he was more lovable—funnier, sillier, needier, more poignantly at war with his demons, more lost, more childishly transparent in his lies and inconsistencies—than the benignant and morally clairvoyant artist/saint that had been made of him, it was still hard not to feel wounded by the part of him that had chosen the adulation of strangers over the love of people closest to him.

What we learn from our students. What they yield.

This is the season during which the work days never end, and the skies darken for long stretches, and the rains come, and the tree limbs scratch their chaos into the tired stucco walls of this house.

This is that season, again.

But last night, through what was cold and what was dark, I made my way by train and collapsed umbrella to the University of Pennsylvania campus, which Al Filreis and Greg Djanikian have turned into a second home for me. I traveled there to hear

New Yorker editor David Remnick speak of journalism—then and now. I traveled to sit with my dear student Kim, and to hear of her life, how it unfolding. I traveled for the chance to chat with the great fiction writer and teacher, Max Apple. I traveled to sit among students intent on learning all they can—there, here, now—and among teachers and working writer/editors (Dick Pohlman, Avery Rome, more) who are generous with their own stories.

A gift, all of it.

James Wood, the critic, in his

New Yorker appraisal (July 5, 2010) of David Mitchell ("The Floating Library: What can't the novelist David Mitchell do?") quotes Henry James:

"If Conrad's great master, Henry James, was right when he said that the novel should press down on "the present palpable intimate" (he used the triad to distinguish the role of the living novel from that of the historical novel), then Mitchell's new book...."

(read to find out)

The point for me, right now, is Present Palpable Intimate and whether or not it can be achieved in an historical novel. I believe it can, or at least, in my own work, I have fought for that. In

Flow, in

Dangerous Neighbors, in a work now in progress, the quest has been to scrub away the sepia, to make the then feel now, to make it essential and current.

That, in any case, has been the quest.

Spring in literature

“March has arrived; the sun is shining; finally – finally! – there’s no snow on the ground. To celebrate, take the Guardian’s quiz on the pleasures of the sweetest season.”

How to Design a Cover in 1:55 seconds

Ever wondered how a book cover comes to be? Check out The Making of a Book Cover time-lapse video that condenses the intense Photoshop compositing and retouching and the painstaking revisions process all in under two minutes.

The Subconscious Shelf

The New Yorker invites you to “lie back, relax, let the good doctors at the Book Bench analyze the contents of your bookshelf.”

From stick figures to sweet flick

Jeff Kinney had a clear template when it came time to adapt his wildly successful Diary of a Wimpy Kid children’s books to the big screen.

Read along as authors write ‘Exquisite Corpse Adventure’ online

Every two weeks a different children’s-book author and illustrator join forces to figure out how to move along the story in the online book “The Exquisite Corpse Adventure.”

Yesterday, inspired by an Elif Batuman book and a James Wood essay in The New Yorker, I wrote about novel names. I absolutely adore those of you who shared your own perspective on this. Sarah and others wondered how I name my characters, and I will admit here that sound has so much to do with my decision making. Sophie suggests a particular kind of person to me—internally focused, quietly questing, curious. Riley, for me, is an artist. Tara is wise, winningly sarcastic, eager for the next thing. Like Melissa, I don't question a name once I find it, and I don't overly freight it with meaning. My own name, Beth, means House of God. That's a whole lot to live up to (I certainly haven't yet), and I've never named a character that.

Yesterday, inspired by an Elif Batuman book and a James Wood essay in The New Yorker, I wrote about novel names. I absolutely adore those of you who shared your own perspective on this. Sarah and others wondered how I name my characters, and I will admit here that sound has so much to do with my decision making. Sophie suggests a particular kind of person to me—internally focused, quietly questing, curious. Riley, for me, is an artist. Tara is wise, winningly sarcastic, eager for the next thing. Like Melissa, I don't question a name once I find it, and I don't overly freight it with meaning. My own name, Beth, means House of God. That's a whole lot to live up to (I certainly haven't yet), and I've never named a character that.

In focusing on names in this blog yesterday, I did not have the opportunity to quote from the beginning of the Wood piece ("Keeping it Real: Conflict, convention, and Chang Rae-Lee's 'The Surrendered'") which also struck me as rich with conversational possibilities. Here it is. I'd love your thoughts:

Does literature progress, like medicine or engineering? Nabokov seems to have thought so, and pointed out that Tolstoy, unlike Homer, was able to describe childbirth in convincing detail. Yet you could argue the opposite view; after all, no novelist strikes the modern reader as more Homeric than Tolstoy.... Perhaps it is as absurd to talk about progress in literature as it is to talk about progress in electricity—both are natural resources awaiting different forms of activation....

Wood goes on to make some very interesting statements about the "lazy stock-in-trade of mainstream realist fiction," but it wouldn't be fair of me to quote him at greater length here (buying magazines helps continue the livelihood of magazines). I encourage you to take a look. I'm eager for your reactions.

Today was the third day of our cold, rainy long weekend here in Maryland. Desperate to entertain our restless preschoolers, my husband and I took them to the mall. Wonder of wonders, we discovered that our high-maintenance children are finally old enough to play quietly at the train table long enough for me to browse in the children's section! Before my blissful browsing time was finally cut short by my son's proclamation of "Ew, stinky diaper," I had amassed a big armful of books to buy with a big, fat gift certificate from my boss, and I am still on a big high. (Writer in bookstore, kid in candy store -- I am equally dangerous in both situations.)

This week we honor the National Day on Writing. Tomorrow is the official day of observation per resolution of the U.S. Senate (!), and I'm sure my English 101 students will be observably more thrilled about their classification essay assignment when I tell them of this momentous occasion. When (if) someone asks about the preposition (why 'on' and not 'of'?), I will have to admit that I am mystified. Anyone?

Like the fervent exercisers among us, there are those who can't start the day without committing their daily 500 words to paper. Then there are the rest of us (professionals and students alike), who have lots to say but might need some measure of encouragement/prodding to get through the whole sweaty ordeal to the Finished Product.

This day is for you (and me). As in a 5-mile run, endorphins and that elusive high may or may not materialize, but at the very least, completion of a writing exercise will provide immediate beneficial results.

Last night I was ellipticizing to The New Yorker (blissful apart from the elliptical part) and found not one but two articles about children's books. The first, nominally about Alloy Entertainment, essentially addresses the question of why kids read and why we write for them. The second article, possibly even more interesting to me as the parent of a "willful" child (and on some days, two), discussed picture books as mirrors on the parenting trends of our times and the messages they send to our kids (and to us).

My children's preschool held its weeklong book fair recently, and my daughter begged daily that we buy her a copy of A Bad Case of Stripes. She is a huge fan of the No, David series (natch), and at the end of the week, she was finally rewarded for her patience. I read her the book that night, and she was mesmerized until halfway through, when she became freaked out. "I don't ever want to read that book again," she declared. I put it away until she's a bit older and didn't think of it again for several weeks.

Meanwhile, I was browsing at the book fair in question when I got a call that there had been a staffing emergency at the community college where I'd previously taught. I happily agreed to cover a class already in progress, though the ensuing childcare juggling meant that Kate had to go to beforecare at her preschool on two days. These made for long days for a little girl and, while she ADORES her school and her teachers and was soon begging to go... at night, she started sleeping in our room. We were tired, we were cranky, and my back really hurt by the time 5 a.m. rolled around and we had 4 people and 1 cat in our (not king-sized) bed.

Kate now suddenly insisted that her room was scary and she "hated" it. I did the math and figured that she must have developed a bad case of clinginess due to the extra hours at school. Finally, on questioning about what was so scary about her room, one day she burst into tears and said, "We should have bought the The Star Wars book!" My exasperated husband explained that he had joked that he would buy her this instead of the book she'd been begging for for days. And suddenly it all made sense. She was petrified. It had all started at the book fair -- because, as she had already told me clearly, that book had scared her!

As I tell my students, words are powerful things (words like "liberal," "socialist," "fascist," "racist" -- how many of us reflexively cringe without really considering what they mean?). Stories and books, a compilation of carefully chosen words, are exponentially more so -- especially if we are four years old and already spend half the day in the world of pretend.

And so, bearing the sacredness of your mission in mind at all times -- write on!

In an effort to help my students avoid cliches, I asked them to write about fall and avoid the following words:

crisp, clear, clean, cool, colorful

I am teaching a class on writing college essays and scholarly papers, and one of my students wrote a lovely poem. I love fall! And I love teaching!

Are blogs dead? Are they being repurposed? Is the air going out of the balloon? Are we really on the edge of a no-book, no-newspaper, no-blog world, content to feed on the 140 characters of Twitter? Or have we already arrived?

Are blogs dead? Are they being repurposed? Is the air going out of the balloon? Are we really on the edge of a no-book, no-newspaper, no-blog world, content to feed on the 140 characters of Twitter? Or have we already arrived?

I was talking with Anna Lefler about all this the other day—spinning out my theories and my unevidentiary evidence—and Anna being Anna (that is, infinitely more connected and tied in than I'll ever be) came back last night quoting an interview with Andrew Keen, author of The Cult of the Amateur and, yes (shudder) a blogger. Keen recently predicted that static blogs (such as the one you are reading, if indeed you are still reading) are on the quick outs, while the sort of "real-time social media personal portal(s)" now being enabled by Wordpress are on the rise. Indeed, in an Editor Unleashed interview with Maria Schneider, Keen declared that "the shy and reticent author" will not survive the near-term future. "Ugly, mute writers," he likewise cautioned, "should probably switch careers."

I read Keen not long after I finished reading Margaret Talbot's fascinating piece in The New Yorker, called "Brain Gain: the underground world of "neuroenhancing" drugs" (I've always been a huge Margaret Talbot fan—perhaps because I, being a very old woman, prefer magazine-y thorough and thoughtful to 140-character nano?). It's the story of a Harvard student, a poker player, and a handful of others (representing the legions of the growing many) who have decided to approach their brains much in the same way that women of a certain age approach their faces: with an eye to cosmetic improvements. Why not off-label Ritalin, a treatment for ADHD, for example, or Provigil, a treatment for narcolepsy, to give oneself a little boost? Why not indulge in what Talbot calls "cognitive enhancers: drugs that high-functioning overcommitted people take to become higher-functioning and more overcommitted"? Why not feed your child "smart pills" to help them get ahead? Why not smart-pill yourself, if it can level the playing field against less old, less ugly, less mute, less reticent colleagues?

Well, hmmm. There are reasons. These are drugs after all, and every drug has side effects, some known, some not yet proven, some physical, and some social. Here, for example, is the Harvard student of Talbot's story, describing papers he's written post-enhancement: "...they're verbose. They're belaboring a point, trying to create this airtight argument, when if you just got to your point in a more direct manner it would have been stronger."

Is this...enhanced? Is this...our future? Is this...what we want? Drugs (taken off label) that perhaps verbose-ify and dilute true content, social media that tolerate no more than 140 characters? My small and unenhanced brain tries to accommodate the two thoughts at once and conjures splatter, refractions, lots said, lost meaning. Clearly, I need someone much younger, much prettier, and infinitely less reticent to help me understand how all of this makes for a better world, the sort we're eager to hand down to our children.

View Next 9 Posts

Comedian and author Andy Borowitz revealed today that The New Yorker has acquired his blog, The Borowitz Report. Starting today, readers will find his satirical pieces

Comedian and author Andy Borowitz revealed today that The New Yorker has acquired his blog, The Borowitz Report. Starting today, readers will find his satirical pieces

The New Yorker recently published

The New Yorker recently published

So true. Thank you for sharing this, Beth!

I have nothing to say about this article I just want to say that I am still laughing about our exchange this morning. You are so funny that you could never be in protracted mourning. There. Full circle!

This is so often in my Thinker - good to find someone in agreement -and it's encouragement to hang on to this belief. Thanks, Beth. Once again, you've hit the mark in my heart. xo

This message has been coming to me from so many different directions lately. It is one I need to hear, and hear often, and it's expressed just beautifully here.

Thank you for being another angel messenger :)