new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Aviation, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 18 of 18

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Aviation in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

In college I wrote a senior paper on the USS Indianapolis which became famously sunk and lost in WWII resulting in the largest recorded shark attack in history. I exchanged letters and phone calls with over 60 of the ship’s survivors (the 47 letters I received are on file with the Indianapolis Historical Society). There were many elements of the Indianapolis story that intrigued me, not the least of which was that it was relatively unknown at the time I was researching it. I couldn’t believe the US Navy lost a ship only to be found by sheer luck or that our history would so effectively lose such a compelling story. (Really – largest recorded shark attack in HISTORY. How do we forget that?) The survivors were, every single one, rather surprised that I would write about them for a college project. It turned out to be a turning point for me and revealed that more than anything, I love to research and write about what is lost.

My grandmother used to pray to St. Anthony when she (or anyone she knew) lost something. (The joke in our family was that she prayed to him so much she called him “Tony”; as they were on a first name basis.) I think a lot about lost houses and lost beaches; the lost places of my childhood. I can’t even drive past the house I grew up in without seeing myself running to my grandmother’s house around the corner through a vacant lot that is a 7-11 now. Everything I knew when I was 10 is changed so much it is as if it never existed at all.

The past few days I have been going over an article on missing aircraft in Alaska. It’s kind of weird, but even when pieces of an aircraft are found, it can still be listed as missing. A certain percentage of the aircraft must be recovered for it to be listed officially as an accident. So small pieces of debris are just evidence of something gone; but not proof that it ever existed at all.

There’s probably something poetic in there somewhere….I’m still not sure how to say it that way though. (I’ll be writing about these airplanes a lot more than just this article. There’s more to tell than fits in 1,000 words.)

In the past couple of years I have spent my time with newly found family photographs, uncovered unbelievable family stories (and the hits keeping coming in that front), made contact with someone with information on a long lost mountain climber and paged through the NTSB reports on aircraft gone missing from decades ago.

And I tried twice to drive past the house I grew up in. Chickened out both times. (And I’m not sorry about that.)

There is an unexpected pattern to my interests these days and I’m very mindful of that. Patterns should not be taken lightly; even when you aren’t consciously creating them.

[Post pic from 2012 – 75B was, once upon a time, one of the aircraft we flew at the Company.]

In The Wright Brothers, David McCullough spins a history both exhaustive and personal, sharing original correspondence and examining secondary characters like the Wright sister, Katharine. With McCullough's signature depth and thoroughness, The Wright Brothers pays captivating homage to the two men who so exemplified the American spirit. Books mentioned in this post Portland Noir (Akashic [...]

It's Christmas Eve, 1957, and a 20 year old pilot has just climbed into the cockpit of his Vampire jet fighter, taking off from an RAF air base in Germany to return to England and home in time for Christmas day.

But ten minutes after taking off, over the North Sea, the pilot runs into his first bit of trouble - the jet's compass is not longer working. Before long, the jet suffers a complete electrical failure and the young pilot needs to call up every bit of emergency information he had received while still in training.

Before long, the pilot is completely lost in the fog over the North Sea and beginning to run out of fuel. Bailing out isn't an option - the fighter jet just isn't made for that and it would most likely mean instant death. Not far from the Norfolk coast, he decides to use a last resort technique - flying triangles in the hope that the odd behavior would be noticed and bring out a rescue plane that could bring the Vampire down safely.

The triangular pattern works, and suddenly, a pilot in an old World War II de Havilland Mosquito fighter with the initials JK on the side is signaling that he understands the problem and will shepherd the Vampire to safety. Shepherding is when the rescue aircraft flies wing-tip to wing-tip with the disabled plane.

The Mosquito shepherds the Vampire slowly into the descent. By now, the Vampire had pretty much run out of fuel. Suddenly, "without warning, the shepherd pointed a single forefinger at me, then forward through the windscreen. It meant, 'There you are, fly on and land.'" At first, the pilot sees nothing. Then, the blur of two parallel lines of lights become visible in the fog. The pilot is able to safely land his Vampire.

After being rescued and brought back to RAF Station Minton, now just a supply depot run by the elderly WWII Flight Lieutenant Marks, things begin to get odd. To begin with, Marks can't imagine how the young pilot found his way to the runway on this now preactically deserted base that had been a thriving hub of RAF pilots and planes during WWII. And, the young pilot doesn't seem to be able to find anyone who knows anything about the pilot in the mosquito who had shepherded him to safety. The whole story begins to become more and more sinister until the young pilot notices an old WWII picture in a room and recognizes the pilot in it standing by his Mosquito with the same JK initials.

But, who is the mysterious shepherd who brought a young pilot to safety on Christmas Eve 1957?

All through the novella, the young pilot provides himself with the rational explanations of how and why everything he experiences happens. And most of the explanations are fine. That is, until he comes to the part about the shepherd, where all rational explanation fails, giving the story its surprise ending.

The Shepherd is a short, 144 page novella written in 1975 by Frederick Forsyth, author of novels like

The Day of the Jackal and

The Odessa File. It is said he wrote

The Shepherd for Christmas as a present for his wife.

This tightly written illustrated story is perfect for Christmas Eve, with its message of hope.

Every year, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation broadcasts a reading of

The Shepherd by Alan Maitland on CBC Radio One. Maitland passed away in 1999, but recordings of him reading

The Shepherd are available, like this wonderful 32 minute reading.

This book is recommended for readers age 14+

This book was purchased for my personal library

Today, August 19th, the U.S. is celebrating National Aviation Day. This day was first established by a presidential proclamation of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1939 to celebrate advances in aviation. The date was chosen to coincide with Orville Wright’s birthday to recognize his contribution, together with his brother Wilbur, to the field of aviation — but it is a holiday meant to recognize all aviators who have advanced the field through their efforts. While the Wright brothers, Charles Lindbergh, and Amelia Earhart come to mind as the premier pioneering pilots, there are many unsung aviators. The books below highlight the stories of some of the most famous early female aviators and are the perfect way to celebrate National Aviation Day!

Night Flight: Amelia Earhart Crosses the Atlantic by Robert Burleigh with illustrations by Wendell Minor (K-3)

Night Flight: Amelia Earhart Crosses the Atlantic by Robert Burleigh with illustrations by Wendell Minor (K-3)

This book tells the story of Amelia Earhart’s historic crossing of the Atlantic on May 20, 1932, which made her the first woman to complete a solo flight across that ocean. The flight was a dramatic one, including both mechanical difficulties and fierce weather and both the prose and the paintings of this book capture the tension of the flight and the elation when Earhart touches down in Ireland. The book also includes a brief biography of Earhart, a list of additional sources on the subject and a fascinating collection of quotations from Earhart’s speeches and publications.

Sky High: The True Story of Maggie Gee by Marissa Moss with illustrations by Carl Angel (K-3)

Sky High: The True Story of Maggie Gee by Marissa Moss with illustrations by Carl Angel (K-3)

Maggie Gee knew from a young age that she wanted to fly planes. It was a dream that stayed with her throughout her childhood and when World War II started, she leapt at the chance to serve her country by flying for the Women Airforce Service Pilots or WASPs. Despite stiff competition for a limited number of spots amongst the WASPs, Maggie succeeded, becoming one of only two Chinese American pilots in the organization. This book traces her path from her childhood dreams to her work as a WASP. An author’s note at the end fills in more details about her life after World War II and includes pictures of Maggie and her family throughout the time covered in the book.

Flying Solo: How Ruth Elder Soared Into America’s Heart by Julie Cummins with illustrations by Malene R. Laugesen (K-3)

Flying Solo: How Ruth Elder Soared Into America’s Heart by Julie Cummins with illustrations by Malene R. Laugesen (K-3)

While many know the story of Amelia Earhart’s flight across the Atlantic, fewer people know that Ruth Elder attempted to become the first woman to fly across the Atlantic years earlier in 1927. Though her attempt was cut short by a malfunction over the ocean, she nevertheless became famous, not only for her attempt but also for her later aviation exploits. This book tells her life story, focusing primarily on her attempt to fly across the Atlantic and her participation in a cross-country air race in 1929. Ruth’s story will excite fans of planes and flying and the illustrations will transport readers back to the 1920’s through their vivid details. The book also includes further sources of information about Ruth’s life as well as a final illustration that highlights a number of other important female aviators.

Fly High! The Story of Bessie Coleman by Louise Borden and Mary Kay Kroeger with illustrations by Teresa Flavin (4-6)

Fly High! The Story of Bessie Coleman by Louise Borden and Mary Kay Kroeger with illustrations by Teresa Flavin (4-6)

This book tells the story of Bessie Coleman, an African American woman who grew up in the south in the late 1800’s with a dream to get an education. When she moved to Chicago in 1915 for a chance at a better life, she discovered aviation and decided to head to France to pursue an opportunity to learn to fly. Once she had her license, Bessie returned to the U.S. where she flew in air shows and gave speeches encouraging others to follow her path. Though the book ends with the tragic tale of her death in a flying accident, the story is sure to inspire those interested in learning to fly.

Amelia Earhart: The Legend of the Lost Aviator by Shelley Tanaka with illustrations by David Craig (4-6)

Amelia Earhart: The Legend of the Lost Aviator by Shelley Tanaka with illustrations by David Craig (4-6)

Illustrated with a combination of paintings and photographs from Amelia Earhart’s life, this book is an impressive biography of a woman who is arguably the most famous female aviator in American history. Starting in her childhood and continuing until her disappearance in 1937, it offers a look into Amelia’s entire life, including aspects that are often glossed over in other books, such as her time as a nurse’s aide in Toronto and her work with two early commercial airlines. Both the pictures and the illustrations bring Amelia to life for readers and a list of source notes and other resources at the end of the book provide lots of options for further reading.

The post Read about female pilots on National Aviation Day appeared first on The Horn Book.

By: Alice,

on 5/20/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Images & Slideshows,

Online products,

ANB,

1932 transatlantic solo flight,

Susan Ware,

view amelia,

earhart,

earhart’s,

online amelia,

162434,

828125,

History,

Biography,

amelia earhart,

America,

Multimedia,

amelia,

flight,

Aviation,

American National Biography,

*Featured,

Add a tag

By Susan Ware

In 1928 Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly the Atlantic Ocean, a feat which made her an instant celebrity even though she was only a passenger, or in her self-deprecating description, “a sack of potatoes.” In 1932 she became the first person since Charles Lindbergh to fly the Atlantic solo, doing it in record time and becoming the first person to have crossed the Atlantic by air twice.

In 1928 Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly the Atlantic Ocean, a feat which made her an instant celebrity even though she was only a passenger, or in her self-deprecating description, “a sack of potatoes.” In 1932 she became the first person since Charles Lindbergh to fly the Atlantic solo, doing it in record time and becoming the first person to have crossed the Atlantic by air twice.

Having received far more credit than she felt she deserved in 1928, “I wanted to justify myself to myself. I wanted to prove that I deserved at least a small fraction of the nice things said about me.” So on 20 May 1932 (the fifth anniversary of Lindbergh’s flight), Amelia Earhart took off from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland in her single-engine bright red Lockheed Vega. The flight, rocked by storms, lasted over 14 hours and landed her in Londonderry, Northern Ireland.

The below map features quotes from Earhart’s acceptance speech of The Society’s Special Medal after her unparalleled achievement. (Please note all pinpoints are approximate as there are no logs of times and coordinates for her flight.)

View Amelia Earhart’s 1932 Transatlantic Solo Flight in a larger map. Or, download the accompanying American National Biography Online Amelia Earhart infographic.

The hundreds of telegrams, tributes, and letters that poured in after the 1932 solo flight testify that women in the United States, indeed throughout the world, took Amelia Earhart’s individual triumph as a triumph for womanhood, a view she herself encouraged. At a White House ceremony honoring her for her flight, she succinctly captured the links between aviation and feminism: “I shall be happy if my small exploit has drawn attention to the fact that women are flying, too.”

With all the mythology surrounding Amelia Earhart’s last flight in 1937, it is hard not to let the unsolved mystery of her disappearance cloud our historical memories. Without that dramatic denouement, however, it seems likely that Amelia Earhart would have been remembered primarily for the skill, daring, and courage demonstrated in her 1932 Atlantic solo. It is the life, not the death, that counts.

Susan Ware is the General Editor of American National Biography Online and author of Still Missing: Amelia Earhart and the Search for Modern Feminism. A pioneer in the field of women’s history and a leading feminist biographer, she is the author and editor of numerous books on twentieth-century US history. Ware was recently appointed Senior Advisor of the Schlesinger Library at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

For more information on Earhart, visit her entry in American National Biography. The landmark American National Biography offers portraits of more than 18,700 men and women — from all eras and walks of life — whose lives have shaped the nation. More than a decade in preparation, the American National Biography is the first biographical resource of this scope to be published in more than sixty years.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Earhart and “old Bessie” Vega 5b c. 1935. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Charting Amelia Earhart’s first transatlantic solo flight appeared first on OUPblog.

Ever since the war began, Molly has been having a hard time dealing with all the changes it brought in her family. Her dad is still in Europe with the army, her mom is busy with her Red Cross work, Jill has been volunteering at the Veteran's Hospital, even Ricky has a job mowing lawns in the neighborhood and younger brother Brad is off to camp every day.

Now, it is August and Molly is visiting her grandparents farm by herself for the first time. Now, here with grandpa, grammy and the familiar smells of her grandmother's kitchen, it feels more like old times to Molly. Until she realizes that her favorite Aunt Eleanor isn't there and when she asked where she is, Molly is told she is away, "as usual" according to grandpa.

But when Molly and grandpa return to the house after picking a melon from the garden, Aunt Eleanor is home. Still, Molly's excitement that she will be able to do the same things with Aunt Eleanor this year that they have always done together on the farm quickly turns to disappointment when she is told that her aunt won't be home the next day.

Later that night, while stargazing, Aunt Eleanor tells Molly she has applied to join the WASPS, or Women Airforce Service Pilots, and that, if accepted, she will be testing and transporting planes for the Air Force, and even helping to train pilots. Molly is not quite as happy about this as Aunt Eleanor would have liked.

Aunt Eleanor leaves early every morning, returning home at suppertime. Molly spends the next few days alone, feeling lonely without her family at the farm, angry at the war and now angry at her aunt, and maybe even a little jealous that she wants to spend Molly visit flying instead of with her. Then, one night, Aunt Eleanor doesn't get home until Molly is already in bed. When she goes in to see if Molly is awake, Molly's anger gets the best of her and she snaps at her aunt, accusing her of not caring about anything anymore, except flying.

The next morning, Aunt Eleanor wakes Molly up very early and tells her to get dressed. In the car, when Molly asks where they are going, all she is told is that she'll see. Arriving at the airfield, Molly and Aunt Eleanor walk over to the plane her aunt has been practicing with. To her surprise, Molly is handed a helmet, told to put it one and the next thing she knows, she and Aunt Eleanor are flying over grandpa's farm.

Can Molly and Aunt Eleanor be reconciled, now that Molly has had a taste of the exhilaration that flying gives her aunt?

Molly Takes Flight is actually a very small book (just 47 pages), one of five separate short stories that were originally published by the Pleasant Company in 1998 about Molly McIntire, an American girl growing up in WWII (the stories has since been combined into a single book, one for each historical doll).

Written by Valerie Tripp, and illustrated by Nick Backes, who have done a number of the original American Girl stories together,

Molly Takes Flight is a well written, well researched short story. It follows the same format that all the stories about the American Girl historical dolls have - a story followed by several pages giving information about the main theme - in the case the WASP program begun in 1942 and organized by Jacqueline Cochran.

Stars also play an important part in this story. Molly looks at the North Star each night, just as her dad told her to, and thinks about him. And she and her aunt star gaze whenever Molly visits the farm. At the end of

Molly Takes Flight, there is a simple, but fun craft project for making a star gazer out of a round oatmeal container.

This copy of

Molly Takes Flight is my Kiddo's original one, and it doesn't feel like that long ago we were reading it together, but now I have it put away with her Molly doll and her other American Girl books for the next generation, whenever that happens. And even though Molly has been retired, her books are still available.

This book is recommended for readers age 8+

This book was purchased for my Kiddo's personal library

By: Colleen Mondor,

on 3/21/2014

Blog:

Chasing Ray

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Aviation,

Add a tag

This is made of awesome from start to finish (and even wing walking!!!)

Not long ago I reviewed a book by John Boyne on my blog

Randomly Reading called

The Terrible Thing that Happened to Barnaby Brocket. This was a really good fantasy novel about a boy who floats and must be weighed down to stay on the ground. Barnaby has a dog named Capt. W.E. Johns, which caused me to laugh when I read that. There is no explanation why that is the dog's name, but I (and others, I am sure) know exactly who Johns is.

Captain W.E. Johns was a very prolific writer with 169 books to his credit. But he is probably best known for two of his series books: 96 'Biggles' books for boys and 11 'Worrals' books for girls. Worrals, or Joan Worralson, flies for the Women's Auxiliary Air Force, part of the RAF. I reviewed

Worrals of the W.A.A.F in 2011. Biggles, or James Bigglesworth, learned to fly in World War I and continued flying right into World War II and beyond.

Biggles Defies the Swastika (#22 in the series and written in 1941), begins in April 1940. A Major with the RAF, Biggles has been doing some work in Oslo when he wakes up one morning to discover that the Nazis have invaded Norway. Fortunately, Biggles has false identity papers naming him as Sven Hendrik, allowing him to pass as a Norwegian who supports the Nazis until he can get to his plane and out of Norway. Arriving at the aerodome in Boda on a stolen Nazi motorcycle, Biggles finds it is under Nazi control now. Somehow, Biggles fools the Germans into thinking he is a quisling who speaks fluent German and is made a

leutnant on the spot by the German commandant there. Now under a safe cover, Biggles gets himself to the Swedish border on a his stolen motorcycle and crosses over to safety.

But not for long. At the British Consul, he is told to return to Norway to do some ntelligence spying and that his friends and fellow fliers Ginger and Algy will contact him as soon as possible. Back in Norway, he hears that the Germans are looking for a British pilot named Bigglesworth who was spotted in Oslo and wanted by the Germans. Luckily, as Sven Hendrik, Biggles is ordered to look for himself and given a Gestapo pass that will allow him freedom to get around without question.

Biggles soon discovers that his old nemesis Oberleutnant Erich von Stalhein is in Norway and is desperate to capture him. Biggles calls Gestapo headquarters and tells them he has information that Bigglesworth is in Narvik and he is on his way there. But along the way, he runs into some captured British sailors. He tells them he's really a British pilot and concocts a plan for them to tell their captors that they saw Bigglesworth escape. In Narvik, Biggles finds other British POWs, including his old friend Algy, who was sent over to help him. He manages to free all the prisoners, but is then ordered back to Boda Aerodome to be questioned by von Stalhein.

Before that can happen, Biggles is ordered to Stavanger airfield by the British to gather intelligence about Nazi defenses there and then to go to Fjord 21, where he runs into his other old friend Ginger. It is time to get out of Norway now that they have the needed intelligence, but Biggles refuse to go with Algy. Meanwhile, Algy, after being freed at Narvik has returned to Boda to find Biggles.

Biggles returns to Boda, finds Algy and they make their way to Fjord 21, Ginger in his plane and escape, only to find that the Fjord is now occupied by Nazis and that Ginger is missing. But not for long. Ginger tries to rescue Biggles and Algy, but things go wrong and Algy is again captured by the Nazis. Biggles, with the help of his Gestapo pass, learns that the British warships are sailing right into a trap. He can do nothing about it though because of growing suspicion about who he really is. He accepts a ride in a water plane back to Boda and von Stalhein, because he has no choice. During the flight, Biggles overtakes the pilot. Flying low enough for the German to jump into the water, Biggles orders him out, but not before telling him they must get together after the war and have dinner together (yes, he really did say that).

***SPOILER ALERT***

Now flying a German plane, Biggles is attacked by none other than Ginger. But then Ginger is attacked by a German plane and goes down. Luckily, Biggles is able to rescue Ginger, tells him about the trap the British warships are heading into and has Ginger drop him off to find Algy. Ginger delivers his warning, sets off to find Biggles and Algy, but is captured by the Germans. Meanwhile, Bigglesand Algy are also captured by von Stalhein at Boda. But when Ginger arrives with his German captor, the three of them manage to overpower him, steal a German plane and fly safely off to England and further adventures - lots of them!

All this action/adventure tokes place in only a few days. The back and forth between Oslo, Boda and Stavanger were a bit like watching a ping pong games with airplanes, but I never got confused, in part because of the simplicity of the writing. It is not great literature, is sometimes politically incorrect and everyone smokes, but Johns seems to have understood his young readers. There is just action, constant movement, and a feeling of being in control, something young readers probably found comforting in wartime Britain.

If you are going to read them for the first time, don't take them too seriously, just have some fun, after all, they feel a bit campy nowadays. And I thought the rivalry between Biggles and von Stalhein had shades of the later rivalry between Snoopy and the Red Baron. I did, however, learn that anti aircraft flak was refered to as archie, as in 'you will probably run into lots of archie when you fly a German Dornier over Britain.'

While I have read most of the Worrals books, I seem to only have

Biggle Defies the Swastika - but I have two copies of it, somehow. And both smell like they just came out of my gram's attic. Luckily, since Biggles is still somewhat popular, now editions of his books have become available recently, for your reading pleasure.

|

| Johns with his novels |

Biggles has has lots of influence on people's lives. Here are some examples:

A Life of Biggles by Hilary Mantal

I Longed to Fly with Biggles by John Crace

Good Eggs and Malted Milk: Has Biggles Stood the Test of Time by Giles Foden

More information on Biggles and his creator Captain W. E. Johns can be found

Collecting Books and Magazines (a great site for all kinds of information about kids books from the past.

This book is recommended for readers age 12+

This book was purchased for my personal library

This is book 3 of my 2013 Pre-1960 Classic Children's Books Reading Challenge hosted by

Turning the Pages

Last April, I reviewed an interactive book from the YouChoose World War II series called

World War II: On the Home Front by Martin Gitlin. I found it to be an excellent book for introducing readers to life on the home front.

Now comes this latest YouChoose adventure, World War II Pilots. The basic premise is that you are given a situation and the story unfolds based on the choices you make at certain junctures of the story. In Chapter 1 of

World War II Pilots, the reader is first given some historical information about the events that led to the war beginning at the end of World War I.

At the end of the chapter, you have 3 choices: to follow the path of a British pilot in the RAF, an American pilot fighting in the Pacific Ocean or a Tuskegee Airman - all very interesting choices. So you choose your path and at the end of each chapter, more choices can be made regarding the fate of the chosen pilot. In fact, there are 36 choices altogether, given each pilot 12 possible ways to go. And in the end, there are 20 different possible endings - 7 for the RAF pilot, & for the American pilot and 6 for the Tuskegee Airman.

I know this all sounds complicated. I also think that, too, whenever I start these kinds of books, but they are designed for young readers and really aren't difficult at all and in fact, they are quite informative without being overwhelming. I actually enjoyed going back and forth and making choices to see where each path led. I also liked the photographs that are included and relevant to the path I was following. For example, when I picked the Pacific Ocean pilot, there were pictures of things like Bataan, or the carrier he might taken off from. I also found that concepts that might not be familiar were clearly explained.

I especially like the back matter. First, there is a timeline of events in the war relevant to the stories. Next, there are suggestions for designing your own World War II pilot stories - a female pilot in the RAF or in the US, a German pilot during the Blitz, a POW held by the Japanese or Germans, all requiring so research and imagination. To help this along, there are suggestions for further reading in print and the Internet, a glossary and an extensive bibliography.

World War II Pilots is an excellent book for leisure reading as well as home schooling and classroom use.

This book is recommended for readers age 9-12

This book was an E-ARC from

Net Galley

Curious? You can download a sample chapter of

World War II Pilots at Capstone Young Readers.

Nonfiction Monday is hosted this week by Laura at

laurasalas

By: Kirsty,

on 12/13/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Literature,

UK,

OWC,

Samuel Johnson,

Oxford World's Classics,

hot air balloons,

Aviation,

Humanities,

james boswell,

*Featured,

OWCs,

dr johnson,

rasselas,

the history of rasselas prince of abissinia,

thomas keymer,

saw—sadler’s,

Add a tag

By Thomas Keymer

One doesn’t associate Samuel Johnson, whose death 228 years ago today ended his lengthy domination of the literary world, with the history of aviation. But ballooning was a national obsession in Johnson’s last year, and he was caught up in the craze despite himself. Several early experiments ended badly (one prototype was pitchforked to shreds as it landed by terrified peasants), but the first manned flights took place successfully in Paris in autumn 1783. Soon the London Chronicle was reporting that “Montgolfier mania” was “endemial both in France and England,” and plans were under way to repeat the exercise in Britain. Johnson researched the enabling technology as reports flowed in from Paris, and a year later he was in Oxford when James Sadler—the doughty Richard Branson of his day—made his celebrated ascent from the University Botanical Garden on 17 November 1784, flying 20 gut-wrenching miles to Aylesbury. Johnson was now severely ill, and the best he could do was witness the event by proxy: “I sent Francis [his beloved Jamaican manservant and heir] to see the Ballon fly, but could not go myself.”

The likelihood is that by this stage he didn’t much mind. Initially, Johnson saw huge potential in balloons for advancing human knowledge, and subscribed to a scientifically motivated scheme for high-altitude flight, which, he wrote, would “bring down the state of regions yet unexplored.” He was fascinated by thoughts of the view from above, though he couldn’t imagine seeing “the earth a mile below me, without a stronger impression on my brain than I should like to feel.” But in time Johnson grew more sceptical about the value of balloons—fragile, combustible, impossible to direct—for either transportation or science, and disease preoccupied him instead: “I had rather now find a medicine that can ease an asthma.” He never makes the analogy explicit, but it’s clear from his last letters that, consciously or otherwise, he came to associate his bloated, dropsical body with a sinking balloon, and his difficulty in breathing with an aeronaut’s struggle to stay inflated. In a gloomy, earthbound message just weeks before death, he seems to glimpse the void in Montgolfier shape. “You see some ballons succeed and some miscarry, and a thousand strange and a thousand foolish things,” he tells the enviably youthful, mobile Francesco Sastres: “But I see nothing; I must make my letter from what I feel, and what I feel with so little delight, that I cannot love to talk of it.”

The likelihood is that by this stage he didn’t much mind. Initially, Johnson saw huge potential in balloons for advancing human knowledge, and subscribed to a scientifically motivated scheme for high-altitude flight, which, he wrote, would “bring down the state of regions yet unexplored.” He was fascinated by thoughts of the view from above, though he couldn’t imagine seeing “the earth a mile below me, without a stronger impression on my brain than I should like to feel.” But in time Johnson grew more sceptical about the value of balloons—fragile, combustible, impossible to direct—for either transportation or science, and disease preoccupied him instead: “I had rather now find a medicine that can ease an asthma.” He never makes the analogy explicit, but it’s clear from his last letters that, consciously or otherwise, he came to associate his bloated, dropsical body with a sinking balloon, and his difficulty in breathing with an aeronaut’s struggle to stay inflated. In a gloomy, earthbound message just weeks before death, he seems to glimpse the void in Montgolfier shape. “You see some ballons succeed and some miscarry, and a thousand strange and a thousand foolish things,” he tells the enviably youthful, mobile Francesco Sastres: “But I see nothing; I must make my letter from what I feel, and what I feel with so little delight, that I cannot love to talk of it.”

Yet there’s also a sense in which Johnson had been talking of balloons for decades. It’s with a fantasy of aerial spectatorship—“Let observation with extensive view / Survey mankind, from China to Peru”—that his poem The Vanity of Human Wishes (1749) begins, as though generalizing about the human condition meant taking, almost literally, a bird’s eye view. His philosophical tale Rasselas (1759) uses human flight to address large questions about ambition and power. The hapless inventor of a flying mechanism enthuses to Rasselas about the philosophical pleasure with which he now, “furnished with wings, and hovering in the sky, would see the earth, and all its inhabitants, rolling beneath him.” Inevitably, the wings then fail to keep him aloft, though when he plunges into a lake—with neat Johnsonian irony—they keep him afloat. This is not only a warning about individual overreach, however. It also lets Johnson consider the implications of flight for global power. Before his embarrassing swim, the inventor assures Rasselas that he will never explain aviation to others, “for what would be the security of the good, if the bad could at pleasure invade them from the sky? … A flight of northern savages [the phrase implies not only ancient Goths but also the powers of modern Europe, then waging war for empire] might hover in the wind, and light at once with irresistible violence upon the capital of a fruitful region that was rolling under them.”

When editing Rasselas a few years ago, I was fascinated to see how often Johnson’s signature effect of timeless truth seemed to spring from odd contingencies. Scholars often situate Johnson’s failed aeronaut in mythical and literary traditions, and in this context it was refreshing to find Pat Rogers’s reading of the episode with reference to a historical stuntman and self-styled “flyer” named Robert Cadman. Cadman was a minor celebrity in the midlands of Johnson’s youth, a tightrope-walker whose trick was to slide down cords from steeple-tops, which he did to acclamation until dying from a fall in 1739. There was also a delightful related source for Johnson’s hovering armies. This was a satirical elegy on Cadman in a magazine for which Johnson was working at the time, which imagines airborne invasion of a rival power by squadrons of flying Cadmans: “An army of such wights to cross the main, / Sooner than Haddock’s fleet, shou’d humble Spain.” (Yes, there really was an Admiral Haddock.)

James Boswell tells a story from 1781 in which, claiming never to have re-read Rasselas since publication, Johnson snatches a copy he sees and turns avidly to a related passage that was now more telling than ever. Again it concerns war and empire, specifically the geopolitical consequences of technological advance in “the northern and western nations of Europe; the nations which are now in possession of all power and all knowledge; whose armies are irresistible, and whose fleets command the remotest parts of the globe.” That technology brings power is not, in itself, an unfamiliar insight. Theoreticians of war from Clausewitz to Virilio have explored its implications, and the basic point would not have been news to the tribesmen crushed by Hittite chariots four millennia ago. Yet Johnson gives it an eloquence all his own, and perhaps he still had Rasselas in mind when he saw—or almost saw—Sadler’s balloon in Oxford three years later, harbinger of airborne blitzkrieg and surgical strikes.

Thomas Keymer is Chancellor Jackman Professor of English at the University of Toronto, where he is also affiliated with University College and with the Collaborative Program in Book History and Print Culture at Massey College. He is the editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia by Samuel Johnson. Rasselas is an established classic, often compared to Voltaire’s Candide, Rasselas is perhaps its author’s most creative work.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: An exact representation of Mr Lunardi’s New Balloon as it ascended with himself 13 May 1785 © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without explicit permission of the British Museum.

The post Samuel Johnson and human flight appeared first on OUPblog.

Imagine being a 13 year old African American boy living in Chicago with your aunt during WWII while your father is away in the Air Force. Imagine further that one morning, out of the blue, your aunt tells you it is time for you to see your father again and that afternoon, without even saying good-bye to your best friend, you find yourself on a train heading to Camp Mackall in North Carolina. Sounds pretty harsh, doesn't it?

Jump into the Sky begins in May 1945. The war has ended in Europe but not in the Pacific. And not in the south either, where Jim Crow stills reigns. Young Levi's first experience of that happens when he changes trains in Washington DC and is put in an almost empty car right behind the coal-burning engines. There he meets an older man who gives him his first lesson in Jim Crow laws.

Levi is astounded by what he hears, so much so he doesn't believe what he has been told until he finds himself looking down the barrel of a gun while trying to buy a Coke in a store at the end of his journey in Fayetteville. He manages to get out of the store alive, though not before experiencing a little more Jim Crow welcome. Afraid and humiliated, Levi starts walking the miles to Camp Mackall, where is father is stationed. Along the way, he is picked up by a black soldier, but discovers that his father, Lieutenant Charles Battle and the rest of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, the country's only all black unit in the Air Force, has been moved on to Oregon.

Luckily for Levi, the one member of his father's Battalion still around because of an injury finds Levi and takes him home, where he ends up living for the first part of the summer. Cal and his wife Peaches both know Levi's father, so there is some comfort in that. And as soon as Cal's injury is healed, he gets his orders to head to Oregon, too. What a surprise when they find that 555th's assignment is to fight fires along the west coast.

In Oregon, the story begins to diverge. On the one hand, Levi and his father had been separated for three years and both have changed a great deal. Now, they must get to know each other and for Levi that means learning to trust his father as well as himself. Levi has a history of people leaving him, including his father and his mother. And now he has an aunt who no longer wants to take care of him. Can things work out somehow so that he and his father can get along and live together?

On the other hand, there is the historical aspect of this novel. Pearsall, who I was surprised to discover is not African American, has managed to convey the scathing hatred most whites had towards blacks in the south. The fact that Levi was so naive about the rules and mores makes his time spent there all the more poignant. Twice I felt myself getting angry and scared for Levi as he went through his baptism by fire.

And there is the other historical aspect - the heroes of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion. No one back in Chicago really believed that his father was really doing what he said he was doing for the war but it turned out to be true, much to Levi's surprise. In Oregon, the 555th were assigned to fight the fires resulting from fire balloons the Japanese were sending over. These balloon bombs carried incendiary devices meant to explode and start fires wherever they landed. Most people really didn't believe this was happening including the men of the 555th, and Pearsall realistically portrays the frustration these men must have really felt after all their elite training and knowing they were being laughed by people. **Not a spoiler, but an historical fact** It turns out, the Japanese really did send over 9,000 of these balloon bombs.

Jump into the Sky is a nice coming of age adventure story with well developed characters and realistic settings. I thought Pearsall gave us a clear, informative window into what life may have been like for some African Americans on the American home front at that time in Chicago, North Carolina and Oregon.

One more thing - why was Aunt Odella so anxious to get rid of Levi? Well, I didn't see the answer to that coming.

This book is recommended for readers age 10+

This book was obtained from the publisher

More information about the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion can be found

here.

Below is a short video of the men of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion training in Oregon

By: Kirsty,

on 11/22/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

US,

china,

airplanes,

plane,

Asia,

This Day in History,

pacific,

flight,

Aviation,

trans,

*Featured,

higher education,

this day in world history,

aeroplanes,

aviation history,

china clipper,

juan trippe,

pan am,

clipper,

trippe,

seaplane,

Add a tag

This Day in World History

November 22, 1935

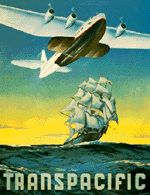

China Clipper makes first trans-Pacific flight

Holding more than 110,000 pieces of mail, the mammoth plane that weighed more than 52,000 pounds and had a 130-foot wingspan lifted from the waters of San Francisco Bay. The plane, the China Clipper, was beginning the first flight across the Pacific Ocean on November 22, 1935—just eight years after Charles Lindbergh had flown alone across the Atlantic.

Holding more than 110,000 pieces of mail, the mammoth plane that weighed more than 52,000 pounds and had a 130-foot wingspan lifted from the waters of San Francisco Bay. The plane, the China Clipper, was beginning the first flight across the Pacific Ocean on November 22, 1935—just eight years after Charles Lindbergh had flown alone across the Atlantic.

Built by the Glenn Martin Company, the China Clipper was a giant seaplane, a design well-suited to its use. The plane had to be massive to carry powerful enough engines and enough fuel to cover the vast expanse of the Pacific. The size and weight meant the plane would need a large runway, uncommon in the 1930s when aviation was just beginning. A seaplane, though, could easily land on water.

Flying across the Pacific was the brainchild of Juan Trippe, president of Pan American Airways, the leading U.S. airline at the time. Trippe knew that even the largest, most powerful plane would not be able to cross the entire Pacific in one flight. He planned to make stops at Honolulu, Midway, Guam, and Wake islands before reaching the plane’s original destination at Manila, in the Philippines. He was there—along with Postmaster General James A. Farley—to send the plane off on its initial flight. Trippe meant the name clipper to evoke the romance of the fastest merchant ships of the days of sail, the clipper ships that for decades had carried on the China trade.

Pan Am added two other planes to its trans-Pacific fleet, the Hawaii Clipper and the Philippine Clipper. Trans-Pacific passenger service was inaugurated in 1936, and that same year the first trip to China took place. Later, the Martin seaplanes were replaced by even more powerful Boeing aircraft.

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.

Adult Novels for Young Adult Readers

continues the story of Velva Jean Hart Bright begun in

Velva Jean Learns to Drive. In this second novel, Jennifer Niven explores the world of the newly formed WASP,or Women Airforce Service Pilots, in World War II through the experiences of her determined, independent, strong-willed 18 year old protagonist, Velva Jean.

Velva Jean had married her preacher husband Harley Bright when she was 16. She saved as much money as possible and learned to drive, enabling her to leave this abusive marriage. When this sequel opens, Velva is driving her yellow truck from her home in Fair Mountain, North Carolina to Nashville, to realize her dreams of singing at the Grand Ole Opry. Her first day in Nashville, August 23, 1941, standing outside the Opry, a tall, striking woman hands her some money thinking she is needy. After the Opry lets out, Velva Jean finds the woman and returns the money to her. The woman, 26 year old Beryl Goss, or Gossie, takes her in, helps her get a job and introduces Velva Jean to Nashville life. The two become fast friends.

Life in Nashville brings other new things to Velva Jean. She teaches herself how to type, gets a job and bombards the head of the Grand Ole Opry with letters asking for an audition. She also receives regular letters from her husband, but refuses to open them and just puts them away.

On May 21, 1942, Velva Jean’s life changes completely when her brother Johnny Clay Hart comes to Nashville. Johnny Clay has signed up to be a paratrooper, but has some time before his training begins. Impatient to start, Johnny Clay finds a flying instructor to take him and Velva Jean up for her first airplane ride. Scared but thrilled, Velva Jean falls in love with flying and begins taking lessons in earnest. Her flying teacher considers her a natural, and when he hands Velva Jean a copy of

Life magazine with an article about two government programs for women pilots, she determines that is what she wants to do, despite being too short, underage and under educated.

Undaunted, however, Velva Jean begins to inundate the head of the WASP program, Jacqueline Cochran, with letters asking for a chance anyway. In October, 1942, she is called in for an interview. In December, Velva Jean is accepted into the WASP program and in February 1943, she leaves Nashville for Texas and pilot training.

Needless to say, Velva Jean has a lot of adventures and experiences, in Nashville, on a visit home to Fair Mountain, in Texas and later at Camp Davis in North Carolina. Some of these involve the usual experiences of loss and love. What really stands out and is the most disturbing are the obstacles that women face while trying to serve their country. In reality, the WASPs really did face many obstacles. Flying was still relatively new, and women fliers were just not readily accepte

By:

nicole,

on 9/21/2011

Blog:

the enchanted easel

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

bedding,

nursery art,

the enchanted easel,

cute,

boys,

airplanes,

whimsical,

transportation,

aviation,

Add a tag

FLYING HIGH!!!

they are made to coordinate with today's popular beddings. and...just because i love to decorate little boy's rooms:)

During the Second World War, Whitman Publishing issued a series of books under the heading "Fighters for Freedom." There seems to have been a total of eight books written for the series – 3 for boy and 5 for girls. These books were, of course, pieces of pure propaganda, but with relatively interesting stories.

Sparky Ames and Mary Mason of the Ferry Command is the story of two non-combatants in World War II. Mary is a part of the WAFS, the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron and Sparky is a pilot with the Ferrying Squadron. He no longer qualified for combat because he has a punctured eardrum, which, he of course, received in earlier heroic combat.

Mary and her flying partner Janet are part of a flying squadron going from the US to Africa to China that includes Sparky and his partner Doug and 38 other planes. But as they are flying over Brazil, Sparky’s plane is hit by enemy fire and he is forced to land in the midst of a native village, with Mary’s plane following close behind. Doug has been seriously injured, but luckily, in the midst of a primitive village, there is a “medicine man” who is really an American educated doctor there to care for him. It is decided that Mary and Sparky would fly together in his plane, attempting to catch up with the rest of the squadron and Janet and Doug would await help.

So off they go. Their first stop is Natal, Brazil for s short rest and to refuel the plane. They are taken to a small city, and while sitting in a canteen, Mary meets a French woman who is very interested in her mission, but the conversation is interrupted by another American girl in uniform. As Mary leaves the canteen, she sees the French woman speaking with a very small man who appears to be an Arab beggar.

Their next stop is at an oasis in an unnamed desert in mid-Africa. Shortly after arriving, Mary sees a Muslim woman dressed in a

Burqa, but believes her to be the same French lady from earlier but in disguise. And a little later, she sees a man with a camel and is sure he is the Arab beggar she had seen speaking to the French woman. After refueling, they take off but no sooner are they in the air then their engine catches fire.

When Sparky goes to the wing to repair the engine, he finds a Japanese man hiding there, having obviously set the fire. They fight (in the wing) and Sparky overpowers him, but merely ties him up, not killing him. When he returns to the cockpit, Mary is convinced he is the same man she saw at both their stops. The engine is repaired, but then enemy planes appear in the sky. A battle ensues and Sparky is able to knock out the enemy planes. Later, he discovers the Japanese man in the wing has died.

Once again, they land for a rest, this time in Egypt, where Mary’s father, Colonel Mason, is stationed. Her father introduces Mary to Captain Burt Ramsey. Mary is immediately attracted to him and spends her time in Egypt with him. Before Mary and Sparky leave Egypt, Mary is asked to carry an ancient roll of papyrus back to the States with her.

Mary and Sparky’s trip continues with stops throughout the Middle East, a treacherous flight through the Himalayans in a blinding snowstorm and an important stop in Burma to deliver some quinine to the

At one time, Inez Hogan was a prolific writer with 63 children’s books to her credit and often illustrated her own stories, as well as those of others. One story she wrote was an odd picture book about gremlins. I usually don’t like books about gremlins because they remind me of that itch that never gets satisfied, no matter how much you scratch.

But gremlins have a place in the history of World War II aviation and Miss Hogan’s book, Listen Hitler! The Gremlins are Coming is an amusing addition to gremlin mythology. The gremlin-aviation myth began in 1923, when they were discovered by the RAF. It seems, gremlins like fooling around with gadgets and planes are full of these. air

Miss Hogan opens here story with a little explanation of who gremlins are by one named Snoopy (no relation to Charles Schultz's Snoopy). Snoopy explains that gremlins have always caused all manner of problems for people, particularly pilots, but no one was bothered by them until World War II.

Snoopy, so called because he has big ears and like to eavesdrop on conversations, is quite indignant after overhearing an RAF pilot telling an American pilot to “watch out for [gremlins.] They are hindering the war for freedom.” Gremlins, he tells us, love freedom; freedom gives Gremlins more opportunities to create chaos.

Snoopy can't get anyone to listen to him because he simply can’t get the other gremlins to stop what they are doing and pay attention to what he is telling them. Instead, they start to reminisce about past accomplishments, providing an opportunity for the author to introduce the different specialties of each gremlin:

Subby specializes in submarines, causing subs to submerge when they shouldn’t, or blocking the periscopes;

Waacy causes havoc for WAACs, running their stockings or ruining their makeup just before inspection;

female gremlins or Fifinellas might untie the shoe laces of soldiers while they are marching;

and young gremlins, called widgets, go after children, doing things like mixing up the scrap they have collected for the war effort.

Warning - This is a Spoiler Event!

W. E. Johns was an extraordinarily prolific British writer with a career that spanned five decades. Altogether he wrote 169 books for boys, girls and adults, as well as editing several magazines about flying. His most famous female character is Flight Officer Joan “Worrals” Worralson. He wrote 11 Worrals novels, beginning in 1941 with

Worrals of the W.A.A.F., which I found to be a fun book about flying and spying.

Worrals, 18, and her best friend Betty “Frecks” (because of her freckles) Lovell, 17, are in service with the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, part of the RAF. The story begins with Worrals and Frecks complaining about how boring their job is simply ferrying aircraft to and from their makers for reconditioning. Worrals had tried flying a fighter plane against rules, but when one needs to be delivered to an RAF outpost, the only person on base who can fly it happens to be Worrals. During this 15 minute flight, a message comes over the plane’s radio that an unknown aircraft had been spotted and was to be stopped at all costs. Naturally, Worrals spots and follows it, sees the plane flying low over a golf course, sees a man running out of the surrounding trees and witnesses something tossed from the plane to the man. She continues to follow the plane as it flies off. Finally, she gets the unknown plane in her sights, presses the button on her plane’s gun control and fires. End of unknown, presumed enemy plane.

Suspecting that something is not right, Worrals and Frecks decide to return to the golf course that weekend. Sure enough, they discover a ring of spies who have created the golf course for the purpose of disguising a hidden runway that small enemy aircraft could use for landing and taking off. Worrals gets caught spying on the spies, but Frecks manages to get away. Worrals is taken to a nearby rectory and locked in a 3rd floor room with one barred window.

Frecks manages to find Worrals and they figure out how to free her and get her back on the ground. Before they get away, the spies come out of the house and the two girls hide on the floor in the back of a car. The spies take off in the car, and the girls overhear their plan to blow up a munitions dump. They arrive at a farmhouse and the girls sneak in to find a phone to warn the RAF of the plan. While there, they discover a map showing future bombing targets. Worrals makes her call, put the map in an envelope and puts it in her pocket just before they are caught by the spies. Worrals finds a gun by the phone and holds the spies off while she and Frecks escape. They take a car in the yard, complete with keys, and a car chase ensues. Worrals manages to mail the map to the air force base, but they are soon stopped by what appears to be a home guard roadblock. Unfortunately, it turns out to be part of the spy ring, set up to stop the girls. They are taken to the vicarage and locked in a room in the cellar. Tired from their escapades, the girls decide to get some sl

By: Julio,

on 5/5/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

American History,

A-Featured,

World War II,

African American Studies,

anderson,

Aviation,

Tuskegee,

Airmen,

Charles Alfred Anderson,

Freedom Flyers,

J. Todd Moye,

forsythe,

moye,

lindbergh,

buehl,

Add a tag

J. Todd Moye is associate professor of history and director of the Oral History Program at the University of North Texas. He previously directed the Tuskegee Airmen Oral History Project for the National Park Service and is the author of Let the People Decide.

In Freedom Flyers: The Tuskegee Airmen of World War II, his latest book, Moye tells the story of the Tuskegee airmen of World War II, a group of African Americans that fought the Axis powers in the skies and racism in their homeland. The following excerpt depicts Charles Alfred Anderson’s fight against discrimination to become a licensed pilot, instructor and eventually, a key figure for the most improbable squad of aviators.

Anderson taught himself to fly well enough to earn his pilot’s license in 1929, making him the second African American to hold one, but he found that he loved flying so much that what he really wanted to do was teach others. To do that, he needed a transport license, and to earn a transport license he needed to find another licensed pilot willing to give him advanced instruction. Again the white pilots he approached turned him down. He finally found a willing instructor with an unlikely background. Ernest Buehl had flown fighter aircraft for the German army in World War I and, according to Anderson, he provided in his dealings with the young pilot that “he was always in favor of white supremacy.” But it did not take Buehl long to decide that Anderson knew what he was doing. When Buehl accompanied Anderson to his test for transportation license in July 1932, the federal inspector told the German immigrant, “You know, I have never given the flight test to a colored person. I don’t know if I will.” According to Anderson, Buehl responded, “Well, he can fly as well as anybody. There is no reason why you shouldn’t give him the test.” Anderson later claimed that he answered every question on the written examination correctly and passed the flight check. The inspector decided that he could not in good conscience fail the black pilot but could not bring himself to award Anderson the perfect score he earned, either. He gave Anderson a score of eighty out of one hundred.

Hungry for anything he could learn about airplanes, Anderson joined the Pennsylvania National Guard with hopes of transferring into an aviation unit. Because the guard did not accept blacks, he tried to pass as white. Anderson was light skinned, but his true racial heritage was soon discovered, and he was kicked out of the service. He tried again to pass as white to enter Pets Aviation School in Philadelphia, but he was asked to leave that program also. With no job prospects in aviation, he dug sewer lines for a time on a Works Progress Administration project.

After news of Anderson’s success in earning a transport license spread through the African American community, Anderson met Dr. Albert E. Forsythe, a black surgeon working in Atlantic City, and agreed to give him flying lessons. Anderson was working for a wealthy white family in Bryn Mawr as a chauffeur and gardener at the time. It was too expensive for him to store and operate an airplane on his own. Forsythe became Anderson’s student and friend, but more importantly for the history of black aviation, his patron. Anderson remembered Forsythe as “a very, very aggressive and determined man, and an ambitious person [who] wanted to advance aviation among the blacks.” He suggested the idea of a transcontinental flight to publicize the cause of black aviation. With Forsythe bankrolling the flight, the pair flew an airplane with no more than a 65- or 70-horse-power engine and a maximum cruising speed of 130 miles an hour from Atla

Night Flight: Amelia Earhart Crosses the Atlantic by Robert Burleigh with illustrations by Wendell Minor (K-3)

Night Flight: Amelia Earhart Crosses the Atlantic by Robert Burleigh with illustrations by Wendell Minor (K-3) Sky High: The True Story of Maggie Gee by Marissa Moss with illustrations by Carl Angel (K-3)

Sky High: The True Story of Maggie Gee by Marissa Moss with illustrations by Carl Angel (K-3) Flying Solo: How Ruth Elder Soared Into America’s Heart by Julie Cummins with illustrations by Malene R. Laugesen (K-3)

Flying Solo: How Ruth Elder Soared Into America’s Heart by Julie Cummins with illustrations by Malene R. Laugesen (K-3) Fly High! The Story of Bessie Coleman by Louise Borden and Mary Kay Kroeger with illustrations by Teresa Flavin (4-6)

Fly High! The Story of Bessie Coleman by Louise Borden and Mary Kay Kroeger with illustrations by Teresa Flavin (4-6) Amelia Earhart: The Legend of the Lost Aviator by Shelley Tanaka with illustrations by David Craig (4-6)

Amelia Earhart: The Legend of the Lost Aviator by Shelley Tanaka with illustrations by David Craig (4-6) In 1928

In 1928

Great review Alex.

I never heard of this series, I'll have to check it out.

http://www.ManOfLaBook.com

Come forward to us & get solution for your income problems ,(11531)

Complete Our 3 day work at home training course and be

placed in a work at home job, with a real company that

will earn you over $50,000 per year Guaranteed!

Earn up to $100,000 Per year from home

as a certified home worker for more details visit: (http://www.JobzInn.com)

Hi Alex, I feel rather ashamed to admit this, but I’ve never read a Biggles story. I’ve sold a few over the years and always admire the artwork on the jackets, but that’s as far as it goes. I really should try to read one, or maybe I will start with a Worrals. I've heard Worrals on the war-path is good.

Thanks, Zohar. This is a British series, but can be found at Amazon.com nowadays. They are campy and fun, nothing serious and so of their time.

Don't feel badly, Barbara, this was my first. I am not surprised you have sold them, they are real collector's items if they are in good shape (mine aren't). I actually liked both Biggles and Worrals, so it would be hard to recommend one or the other. They have that same kind of feeling early Nancy Drew's have, but lots more action. And they don't take long to read. Give it a whirl - it might be fun.

I have never read any Biggle books- but they do sound great. This was an excellent review (I always love your reviews and learn about so many great books). Thanks!

Thanks, Stephanie, I am happy to hear that. I always enjoy your blog post as well over at The Secret DMS Files of Fairday Morrow as well.