new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Books for the News, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 543

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Books for the News in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

“Existentialist Twins”*

Although few Americans had read The Stranger in French—it had been hard enough to find a copy in wartime France—word of the novel had crossed the ocean. Blanche Knopf had founded the US publishing house Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., with her husband Alfred in 1945, and she had a special interest in publishing English translations of contemporary European literature. She had been cut off from France for the duration of the war, but by February 1945 she was back in touch with Jenny Bradley, Knopf’s agent in Paris. Sartre had lauded a new Camus novel, still in manuscript, called The Plague, in a lecture he gave at Harvard, and Blanche Knopf cabled Bradley, asking to see the proofs. The Plague, with its link to the suffering and heroism of France during the German occupation, was bound to make a splash, and she understood that Knopf might also have to buy The Stranger in order to get it. Alfred Knopf cabled Bradley in February, eager to acquire The Plague, although Camus hadn’t yet finished it, but he was still hesitating about The Stranger. In March 1945, he made up his mind and offered $350 for it.

***

Not an ideological or interpretive divide, not even an aesthetic quarrel, but rather a question of timing and marketing explains why L’Étranger and The Outsider were born into the English language as fraternal twins—same text, different typography, covers, and titles. The doubling has continued to this day, even as new translations have replaced Gilbert’s: no matter who is translating, the British edition is called The Outsider, the American edition The Stranger. Books about The Stranger/The Outsider, when they’re published in both the United States and England, have to keep the titles straight for each country or risk disorienting readers. If you ask someone, English or American, which title they prefer, chances are they will answer: “the one I’m used to.”

In England, Jamie Hamilton was certain he had a bestseller on his hands, and he planned a first print run of 10,000 copies—over twice Gallimard’s wartime print run on 4,400. At Knopf, there was much more hesitation. In-house readers’ reports were less than stellar.

Herbert Weinstock, a specialist in nineteenth-century opera and a Knopf advisor, had this to say about the novel: “This extended short story (the translation does not exceed 30,000 words) is a pleasant, unexciting reading. It seems to me neither very important nor very memorable—and it also seems to me to be padded with extraneous detail.” He attributed the piling up of details, the flat tone, and what he called “deliberate artlessness” to a “philosophic theory called existentialism,” of which The Stranger could be considered a demonstration: “My best guess is that it will appeal to very few readers and produce something less than a sensation”

Knopf’s publicists had a formidable task. As The Stranger was about to go on sale in American bookstores, the publisher placed a full-page advertisement in Publishers Weekly (an American trade magazine for publishers, librarians, booksellers, and literary agents). It was signed by Blanche Knopf and entitled “On the New Literature of France.” Jamie Hamilton referred to it as “Blanche’s existentialist ad.” She was going to do everything possible to make The Stranger accessible and exciting.

The advertisement began by sympathizing with the average reader’s dilemma: “There is no use trying to talk about new French literature unless you are willing to tackle ‘existentialism.’ Now this is a frightening word. . . . Everyone likes to show that he can pronounce it, but no one enjoys undertaking to define it. Well, here goes.”

Existentialism, the ad continued, is the notion that a consciousness of the universe’s meaninglessness can make us free. Passing mention was then made of the fact that Camus, whose somber countenance gazed out from the upper right of the page, refused to be classified with the existentialists, because their emphasis on meaninglessness was at odds with his belief in political justice. The author of The Stranger was introduced as a man who had lived a double life during the Occupation—publishing with the approval of the Nazi censor while editing a Resistance newspaper underground. The Stranger was then presented in a few words—a novel as simple and straightforward as John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.

Pitching The Stranger as both a lofty existentialist work and a straightforward populist novel was clever, since reviewers could take up either strand, high or low. Pitching Camus as an existentialist and a champion for social justice was also a good idea—here was an author both intelligent and heroic. After a month of what Blanche Knopf considered “fantastic” press, 2,500 copies of the novel had sold. In 1946, The Stranger was not yet a bestseller. In the long run, the ad accomplished something more important than immediate sales: it introduced Camus to American magazine and newspaper publishers as a leading figure of a school of French literature called “existentialist,” and it established that school as the most important new intellectual current coming out of France.

You would have to read the advertisement in Publishers Weekly more than once to glean that Camus disavowed the existentialist label, and that in fact he detested it. He joked in an interview with a French magazine that he and Sartre decided they ought to put out their own ad “stating that the undersigned have nothing in common and refuse to respond to any debts they might have incurred mutually.” Yet it was Sartre who prepared the way for Camus’s New York welcome.

New York had been a privileged refuge for exiled intellectuals during the Occupation years, and as of 1945, when travel became possible once again on the big liberty and cargo ships, Sartre, Camus, and Beauvoir all made the trip. Sartre was first. In spring 1945, he filed stories from New York for both Combat and Le Figaro, and he returned in 1946 to speak to American universities about the literary scene in Paris.

In Vogue magazine, in 1945, Sartre described Camus as the emblematic writer to emerge from the Resistance—the only writer who corresponded to his theory of a “committed literature” essential to France’s renewal. Sartre had read an early version of Camus’s forthcoming novel, The Plague, in manuscript, and he was ready to vouch that the world was about to see a new Camus: the absurdity of the world in The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus gave way in this new work to positive revolt and struggle. The Plague, based on Camus’s own commitment to the Resistance, demonstrated that the human spirit could come to rule over “the absurd world.” Sartre described, as he had done in the Cahiers du Sud essay in 1943, Camus’s somberness and his debt to the classical moralists, though now he underlined the potential of those qualities for a literature to come: “It is likely that in the somber, pure work of Camus are discernible the principal traits of the French letters of the future.”

For Sartre, Camus represented most vividly the aspirations of postwar literature at a shining moment when writers and intellectuals felt the world was theirs to remake. No other writer could have fit the bill for Sartre: Malraux was too much of an individualist; Guéhenno and Mauriac, much older men, had refused to publish above ground, and the Communists were indebted to their own masters. Camus had done exactly what needed to be done during the Occupation: he had marked time but he hadn’t accepted the oppression; he had chosen struggle rather than silence. At thirty-two years old in 1945, he had reached the perfect age when youth meets maturity.

In January 1946, speaking to students at Yale about the French view of the American novel, Sartre singled out The Stranger as “the French novel which caused the greatest furor between 1940 and 1945.” He placed his emphasis differently in this American context than he had in his Cahiers du Sud essay of 1943. Gone in his American lecture are references to Voltaire and the eighteenth-century morality tale. His focus now was on Camus’s debt to Hemingway, the short disruptive sentences that in Hemingway were a feature of the writer’s temperament but in Camus were rather a deliberate technique for expressing a philosophy of the absurd. Sartre entertained his audience with stories of the symbolic value of American literature when France was under German Occupation. He described the Café de Flore as the headquarters for a black market in American books. Not only did reading Faulkner and Hemingway novels become a symbol of resistance, he claimed, it was even the case—he couldn’t resist a joke—that secretaries “believed they could demonstrate against the Germans by reading Gone with the Wind in the Metro.” Sartre promised his audience, three months before the English-language publication of The Stranger, that French novels written during the Occupation would start to appear in translation. He was rolling out a thick red carpet for his friend.

*This excerpt has been adapted from Looking for “The Stranger”: Albert Camus and the Life of a Literary Classic by Alice Kaplan (2016).

***

To read more about Looking for “The Stranger,” click here.

“Doctrinal Problems”*

It may seem odd that we see so many constraints on expression in traditional public forums in light of today’s generally permissive First Amendment landscape. In recent years, the Supreme Court has upheld the First Amendment rights of video gamers, liars, and people with weird animal fetishes. But in most cases involving the public forum—cases where speech and assembly might actually matter to public discourse and social change—courts have been far less protective of civil liberties.

Part of the reason for this more tepid judicial treatment of the public forum is a formalistic doctrinal analysis that has emerged over the past half-century. Courts allow governmental actors to impose time, place, and manner restrictions in public forums. These restrictions must be “reasonable” and “neutral,” and they must “leave open ample alternative channels for communication of the information.”

The reasonableness requirement is an inherently squishy standard that can almost always be met. The neutrality requirement means that restrictions on a public forum must avoid singling out a particular topic or viewpoint. For example, they cannot limit only political speech or only religious speech (content-based restrictions0. And they cannot limit only political speech expressing Republican values or only religious speech expressing Jewish beliefs (viewpoint-based restrictions). It turns out to be pretty easy for government officials to satisfy the neutrality requirement.

The requirement of “ample alternative channels” introduces another highly subjective standard. Lower courts have found that an alternative is not sufficiently ample “if the speaker is not permitted to reach the intended audience” or if the distance between speaker and audience is so great that only those “with the sharpest eyesight and most acute hearing have any chance of getting the message.” But the ampleness standard is otherwise underspecified. At least one federal appellate court has concluded that an alternative venue need not be within “sight and sound” of the intended audience.

The Supreme Court’s only recent consideration of the ampleness standard came in its deeply divided opinion in Hill v. Colorado, which upheld a public forum restriction that had been challenged by anti-abortion protestors. The majority opinion concluded that the restriction left open “ample alternative channels for communication” and did “not entirely foreclose any means of communication.” Justice Anthony Kennedy warned in dissent that “our foundational First Amendment cases are based on the recognition that citizens, subject to rare exceptions, must be able to discuss issues, great or small, through the means of expression they deem best suited to their purpose.” Kennedy insisted “it is for the speaker, not the government, to choose the best means of expressing a message.” That sentiment echoes Justice William Brennan’s assertion in an earlier case: “The government, even with the purest of motives, may not substitute its judgment as to how best to speak for that of speakers and listeners; free and robust debate cannot thrive if directed by the government.” The underspecified ampleness standard can substantially hinder these goals.

As long as the requirements of reasonableness, neutrality, and ample alternative channels are met, officials can limit the duration and time of day when public forums can be used, the location of an expressive event, and the way in which ideas are conveyed. In principle, these restrictions make sense. In practice, they have been used to control and mute expression and voice.

Consider, for example, how restrictions on time can sever the link between message and moment. Closing a public forum for periods of time that encompassed symbolic days of the year like September 11, August 6 (the day the United States detonated an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima), or June 28 (the anniversary of the Stonewall Riots) could stifle political dissent. Time restrictions that closed the public sidewalks outside of prisons on days of executions, outside of legislative buildings on days of votes, or outside of courthouses on days that decisions are announced, would raise similar concerns. Yet all of these restrictions are arguably permissible under current doctrine.

Restrictions on place that preclude access to symbolic settings can be similarly distorting. As law professor Timothy Zick has noted, “Speakers like abortion clinic sidewalk counselors, petition gatherers, solicitors, and beggars seek the critical expressive benefits of proximity and immediacy.” Zick observes that current doctrine means “individuals who wish to engage in speech, assembly, and petition activities are too often displaced by a variety of regulatory mechanisms, including the construction of ‘speech zones.'” Take, for example, a labor protest. A strike that occurs in front of an employer’s business rather than blocks or miles away not only communicates to a different audience but also conveys different meanings.

Restrictions on manner can drain an expressive message of its emotive content. A ban on singing could weaken the significance of a civil rights march, a funeral procession, or a memorial celebration. Manner restrictions can also eliminate certain classes of people from the forum altogether. That might be true of a requirement that all expression be conveyed by handbills or leaflets rather than by posters. As Supreme Court Justice William Brennan once observed, “The average cost of communicating by handbill is . . . likely to be far higher than the average cost of communication by poster. For that reason, signs posted on public property are doubtless ‘essential to the poorly financed causes of little people.'”

Under current doctrine, the state’s regulation of public spaces through time, place, and manner restrictions is too easily justified apart from serious inquiry into the implications of those restrictions. A government official can usually come up with some reason to regulate expressive activity, some explanation of neutrality, and some argument that an ample alternative for communication exists. But the First Amendment should require more than just any justification to overcome its presumptive constraint against government action.

Sometimes the government can go to even greater extremes than the latitude afforded under time, place, and manner restrictions. Under an evolving doctrine known as government speech, the government can characterize some expression as distinctively its own and not subject to any First Amendment review.

Not all applications of the government speech doctrine are problematic; some cases are easy to understand. When the City of Pawnee hosts a tribute to black history on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, it is “speaking” a message consistent with Dr. King’s values. To that end, it need not ensure that members of the Ku Klux Klan have an opportunity to present their perspective. The event is premised on government speech rather than on facilitating a diversity of viewpoints and ideas.

Even though we can readily grasp the easy cases, the government speech doctrine is fiercely contested by courts and legal scholars because the line drawing it requires beyond those easy cases is impossible to configure. And without any lines—if the government could claim its own speech in any possible forum—the doctrine would swallow the First Amendment.

The Supreme Court unwisely gestured toward the possibility of the unrestricted government speech doctrine in its 2009 decision Pleasant Grove v. Summum. In that case, an obscure religious group called Summum wanted to erect a stone monument in a city park in Pleasant Grove City, Utah. Summum argued that because Pleasant Grove’s park was a traditional public forum, the city could not limit the privately donated monuments in the park to those representing certain mainstream groups, like a statue of the Ten Commandments. The city responded that the park space was a limited resource that could only accommodate a limited number of monuments, and insisted that it could choose which ones to include. In some ways the city’s argument makes sense—public parks are finite resources and cannot possibly accommodate every monument that every person wanted to contribute. But rather than addressing that issue within a public forum analysis, the Supreme Court ducked the issue by designating the monuments in the city par as government speech. That meant Pleasant Grove could decide which monuments to allow and which ones to prohibit. Sidestepping the public forum analysis avoided the hard work that courts and officials should be required to undertake in these settings.

*This excerpt has been adapted (without endnotes) from Confident Pluralism: Surviving and Thriving through Deep Difference by John D. Inazu (2016).

***

To read more about Confident Pluralism, click here.

Though perhaps best known in the United States for his fiction, Bengali writer Amitav Ghosh has previously published several acclaimed works of non-fiction. His latest book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable tackles an inescapably global theme: the violent wrath global warming will inflict on our civilization and generations to come, and the duty of fiction—as the cultural form most capable of imagining alternative futures and insisting another world is possible—to take action.

From a recent starred review in Publishers Weekly:

In his first work of long-form nonfiction in over 20 years, celebrated novelist Ghosh (Flood of Fire) addresses “perhaps the most important question ever to confront culture”: how can writers, scholars, and policy makers combat the collective inability to grasp the dangers of today’s climate crisis? Ghosh’s choice of genre is hardly incidental; among the chief sources of the “imaginative and cultural failure that lies at the heart of the climate crisis,” he argues, is the resistance of modern linguistic and narrative traditions—particularly the 20th-century novel—to events so cataclysmic and heretofore improbable that they exceed the purview of serious literary fiction. Ghosh ascribes this “Great Derangement” not only to modernity’s emphasis on this “calculus of probability” but also to notions of empire, capitalism, and democratic freedom. Asia in particular is “conceptually critical to every aspect of global warming,” Ghosh attests, outlining the continent’s role in engendering, conceptualizing, and mitigating ecological disasters in language that both thoroughly convinces the reader and runs refreshingly counter to prevailing Eurocentric climate discourse. In this concise and utterly enlightening volume, Ghosh urges the public to find new artistic and political frameworks to understand and reduce the effects of human-caused climate change, sharing his own visionary perspective as a novelist, scholar, and citizen of our imperiled world.

To read more about

The Great Derangement, click

here.

Reader’s note: last year, to honor the anniversary of the Mann Gulch wildfire, we posted the below note, along with an excerpt from Norman Maclean’s Young Men and Fire. Today marks 67 years since the events of August 5, 1949, so in tribute, we repost the excerpt and its accompanying introduction. More on the matter, of course, can be gleaned from Maclean’s singular work, while additional background on its author can be found in this weekend’s New York Times Magazine, where a piece on fly-fishing in Montana turns into a meditation on Maclean’s writing and life.

***

August 5, 2015, marks the 66th anniversary of the Mann Gulch wildfire, which eventually spread to cover 4,500 acres of Montana’s Gates of the Mountain Wilderness in Helena National Forest, and claimed the lives of 12 of the 15 elite US Forest Service Smokejumpers, who acted as first responders in the moments before the blaze jumped up a slope and “blew up” its surrounding grass. Haunted by the event, Montana native, author, and former University of Chicago professor Norman Maclean devoted much of his life’s work to researching and writing an account of the events that unfolded that first week of August 1949, which would met publication posthumously two years after Maclean’s death as Young Men and Fire. The book, now considered a classic reconstruction of an American tragedy and a premier piece of elegiac memoir qua historical non-fiction, went on to win a National Book Critics Circle Award in 1992. Below follows an excerpt.

***

Then Dodge saw it. Rumsey and Sallee didn’t, and probably none of the rest of the crew did either. Dodge was thirty-three and foreman and was supposed to see; he was in front where he could see. Besides, he hadn’t liked what he had seen when he looked down the canyon after he and Harrison had returned to the landing area to get something to eat, so his seeing powers were doubly on the alert. Rumsey and Sallee were young and they were crew and were carrying tools and rubbernecking at the fire across the gulch. Dodge takes only a few words to say what the “it” was he saw next: “We continued down the canyon for approximately five minutes before I could see that the fire had crossed Mann Gulch and was coming up the ridge toward us.”

Neither Rumsey nor Sallee could see the fire that was now on their side of the gulch, but both could see smoke coming toward them over a hogback directly in front. As for the main fire across the gulch, it still looked about the same to them, “confined to the upper third of the slope.”

At the Review, Dodge estimated they had a 150- to 200-yard head start on the fire coming at them on the north side of the gulch. He immediately reversed direction and started back up the canyon, angling toward the top of the ridge on a steep grade. When asked why he didn’t go straight for the top there and then, he answered that the ground was too rocky and steep and the fire was coming too fast to dare to go at right angles to it.

You may ask yourself how it was that of the crew only Rumsey and Sallee survived. If you had known ahead of time that only two would survive, you probably never would have picked these two—they were first-year jumpers, this was the first fire they had ever jumped on, Sallee was one year younger than the minimum age, and around the base they were known as roommates who had a pretty good time for themselves. They both became big operators in the world of the woods and prairies, and part of this story will be to find them and ask them why they think they alone survived, but even if ultimately your answer or theirs seems incomplete, this seems a good place to start asking the question. In their statements soon after the fire, both say that the moment Dodge reversed the route of the crew they became alarmed, for, even if they couldn’t see the fire, Dodge’s order was to run from one. They reacted in seconds or less. They had been traveling at the end of the line because they were carrying unsheathed saws. When the head of the line started its switchback, Rumsey and Sallee left their positions at the end of the line, put on extra speed, and headed straight uphill, connecting with the front of the line to drop into it right behind Dodge.

They were all traveling at top speed, all except Navon. He was stopping to take snapshots.

•

The world was getting faster, smaller, and louder, so much faster that for the first time there are random differences among the survivors about how far apart things were. Dodge says it wasn’t until one thousand to fifteen hundred feet after the crew had changed directions that he gave the order for the heavy tools to be dropped. Sallee says it was only two hundred yards, and Rumsey can remember. Whether they had traveled five hundred yards or two hundred yards, the new fire coming up the gulch toward them was coming faster than they had been going. Sallee says, “By the time we dropped our packs and tools the fire was probably not much over a hundred yards behind us, and it seemed to me that it was getting ahead of us both above and below.” If the fire was only a hundred yards behind now it had gained a lot of ground on them since they had reversed directions, and Rumsey says he could never remember going faster in his life than he had for the last five hundred yards.

Dodge testifies that this was the first time he had tried to communicate with his men since rejoining them at the head of the gulch, and he is reported as saying—for the second time—something about “getting out of this death trap.” When asked by the Board of Review if he had explained to the men the danger they were in, he looked at the Board in amazement, as if the Board had never been outside the city limits and wouldn’t know sawdust if they saw it in a pile. It was getting late for talk anyway. What could anybody hear? It roared from behind, below, and across, and the crew, inside it, was shut out from all but a small piece of the outside world.

They had come to the station of the cross where something you want to see and can’t shuts out the sight of everything that otherwise could be seen. Rumsey says again and again what the something was he couldn’t see. “The top of the ridge, the top of the ridge.

“I had noticed that a fire will wear out when it reaches the top of a ridge. I started putting on steam thinking if I could get to the top of the ridge I would be safe.

“I kept thinking the ridge—if I can make it. On the ridge I will be safe… I forgot to mention I could not definitely see the ridge from where we were. We kept running up since it had to be there somewhere. Might be a mile and a half or a hundred feet—I had no idea.”

The survivors say they weren’t panicked, and something like that is probably true. Smokejumpers are selected for being tough, but Dodge’s men were very young and, as he testified, none of them had been on a blowup before and they were getting exhausted and confused. The world roared at them—there was no safe place inside and there was almost no outside. By now they were short of breath from the exertion of their climbing and their lungs were being seared by the heat. A world was coming where no organ of the body had consciousness but the lungs.

Dodge’s order was to throw away just their packs and heavy tools, but to his surprise some of them had already thrown away all their equipment. On the other hand, some of them wouldn’t abandon their heavy tools, even after Dodge’s order. Diettert, one of the most intelligent of the crew, continued carrying both his tools until Rumsey caught up with him, took his shovel, and leaned it against a pine tree. Just a little farther on, Rumsey and Sallee passed the recreation guard, Jim Harrison, who, having been on the fire all afternoon, was now exhausted. He was sitting with his heavy pack on and was making no effort to take it off, and Rumsey and Sallee wondered numbly why he didn’t but no one stopped to suggest he get on his feet or gave him a hand to help him up. It was even too late to pray for him. Afterwards, his ranger wrote his mother and, struggling for something to say that would comfort her, told her that her son always attended mass when he could.

It was way over one hundred degrees. Except for some scattered timber, the slope was mostly hot rock slides and grass dried to hay.

It was becoming a world where thought that could be described as such was done largely by fixations. Thought consisted in repeating over and over something that had been said in a training course or at least by somebody older than you.

Critical distances shortened. It had been a quarter of a mile from where Dodge had rejoined his crew to where he had the crew reverse direction. From there they had gone only five hundred yards at the most before he realized the fire was gaining on them so rapidly that the men should discard whatever was heavy.

The next station of the cross was only seventy-five yards ahead. There they came to the edge of scattered timber with a grassy slope ahead. There they could see what is really not possible to see: the center of a blowup. It is really not possible to see the center of a blowup because the smoke only occasionally lifts, and when it does all that can be seen are pieces, pieces of death flying around looking for you—burning cones, branches circling on wings, a log in flight without a propeller. Below in the bottom of the gulch was a great roar without visible flames but blown with winds on fire. Now, for the first time, they could have seen to the head of the gulch if they had been looking that way. And now, for the first time, to their left the top of the ridge was visible, looking when the smoke parted to be not more than two hundred yards away.

Navon had already left the line and on his own was angling for the top. Having been at Bastogne, he thought he had come to know the deepest of secrets—how death can be avoided—and, as if he did, he had put away his camera. But if he really knew at that moment how death could be avoided, he would have had to know the answers to two questions: How could fires be burning in all directions and be burning right at you? And how could those invisible and present only by a roar all be roaring at you?

•

On the open slope ahead of the timber Dodge was lighting a fire in the bunch grass with a “gofer” match. He was to say later at the Review that he did not think he or his crew could make the two hundred yards to the top of the ridge. He was also to estimate that the men had about thirty seconds before the fire would roar over them.

Dodge’s fire did not disturb Rumsey’s fixation. Speaking of Dodge lighting his own fire, Rumsey said, “I remember thinking that that was a very good idea, but I don’t remember what I thought it was good for.… I kept thinking the ridge—if I can make it. On the ridge I will be safe.”

Sallee was with Rumsey. Diettert, who before being called to the fire had been working on a project with Rumsey, was the third in the bunch that reached Dodge. On a summer day in 1978, twenty-nine years later, Sallee and I stood on what we thought was the same spot. Sallee said, “I saw him bend over and light a fire with a match. I thought, With the fire almost on our back, what the hell is the boss doing lighting another fire in front of us?”

It shouldn’t be hard to imagine just what most of the crew must have thought when they first looked across the open hill-side and saw their boss seemingly playing with a matchbook in dry grass. Although the Mann Gulch fire occurred early in the history of the Smokejumpers, it is still their special tragedy, the one in which their crew suffered almost a total loss and the only one in which their loss came from the fire itself. It is also the only fire any member of the Forest Service had ever seen or heard of in which the foreman got out ahead of his crew only to light a fire in advance of the fire he and his crew were trying to escape. In case I hadn’t understood him the first time, Sallee repeated, “We thought he must have gone nuts.” A few minutes later his fire became more spectacular still, when Sallee, having reached the top of the ridge, looked back and saw the foreman enter his own fire and lie down in its hot ashes to let the main fire pass over him.

***

To read more about Young Men and Fire, click here.

From a recent review of Jooyoung Lee’s Blowin’ Up: Rap Dreams in South Central, at Pop Matters:

One of the many powers of hip-hop, of course, is the intimacy it offers. Spend enough time listening to a certain rapper, and you begin to feel like you know that person as well as you do your own friends. Chuck D’s famous pronouncement that hip-hop is “CNN for black people”, pointed though it is, seems to miss part of the story. Hip-hop is CNN for white people, too, if you acknowledge the media’s systematic neglect of America’s black population. Through hip-hop, rappers are telling the stories that many journalists, and their publications, couldn’t be bothered to cover.

As a white hip-hop fan, there’s a seductive tendency to congratulate one’s self for gaining cultural competencies in African American culture, as if memorizing Tupac lyrics and attending Wu-Tang concerts confers a master’s degree in black studies. But the truth is that even in its rawest, most detailed form, hip-hop gives only what is at best a keyhole-sized view of the African American experience.

Jooyoung Lee’s Blowin’ Up: Rap Dreams in South Central represents a jump through the keyhole into the world of hip-hop as it is lived by some of the art form’s most dedicated practitioners.

To read more about Blowin’ Up, click here.

Just in time for this weekend’s unofficial “start of summer” gong, Nature (yea, that Nature—though also, ostensibly, “nature,” the wilder of nouns, not that other one qua Lucretius’s De rerum natura) came through with a review of Lisa-ann Gershwin’s Jellyfish: A Natural History. Stuck behind a paywall? Here it is in its glory, for your holiday reads:

One resembles an exquisitely ruffled and pleated confection of pale silk chiffon; another, a tangle of bioluminescent necklaces cascading from a bauble. Both marine drifters (Desmonema glaciale and Physalia) feature in jellyfish expert Gershwin’s absorbing coffee-table book on this transparent group with three evolutionary lineages. Succinct science is intercut with surreal portraiture — from the twinkling Santa’s hat jellyfish (Periphylla periphylla) to the delicate blue by-the-wind sailor (Velella velella).

To read more about Jellyfish, click here.

From “Live through This,” by Catherine Hollis, her recent essay at Public Books on how much of our own lives we construct when we read and write memoirs:

In The Dead Ladies Project: Exiles, Expats, and Ex-Countries, Jessa Crispin, the scrappy founding editor of Bookslut and Spolia, finds herself at an impasse when a suicide threat brings the Chicago police to her apartment. She needs a reason to live, and turns to the dead for help. “The writers and artists and composers who kept me company in the late hours of the night: I needed to know how they did it.” How did they stay alive? She decides to go visit them—her “dead ladies”—in Europe, and leave the husk of her old life behind. Crispin’s list includes men and women, exiles and expatriates, each of whom is paired with a European city. Her first port of call is Berlin, and William James. Rather than explicitly narrating her own struggle, Crispin focuses on James’s depressive crisis in Berlin, where as a young man he learned how to disentangle his thoughts and desires from his father’s. Out of James’s own decision to live—“my first act of free will shall be to believe in free will”—the rest of his life takes shape. Crispin reconstructs what it might have felt like to be William James before he was William James, professor at Harvard and author of The Varieties of Religious Experience. If he can live through the uncertainty of a life-in-progress, so too might she.

But not before checking in with Nora Barnacle in Trieste, Rebecca West in Sarajevo, Margaret Anderson in the south of France, W. Somerset Maugham in St. Petersburg, Jean Rhys in London, and the miraculous and amazing surrealist photographer Claude Cahun on Jersey Island. Through each biographical anecdote, each place, Crispin analyzes some issue at work in her own life: wives and mistresses, revolutionaries with messy love lives, and the problem of carting around a suicidal brain. Crispin travels with one suitcase, but a good deal of emotional baggage. While she focuses on each subject’s pain, what she’s seeking is how these writers and artists alchemized their suffering into art, and how that transmutation opens up an individual’s story to others. . . .

In the end, learning how other women and men decided to live helps Crispin decide that suicide is a failure of imagination. “Here is something else you could do,” Crispin’s ladies tell her; here is some other way to live.

To read the piece in full at Public Books, click here.

To read more about The Dead Ladies Project, click here.

Our free e-book for March is Ebert’s Best by Roger Ebert. Download your copy here.

***

Roger Ebert is a name synonymous with the movies. In Ebert’s Bests, he takes readers through the journey of how he became a film critic, from his days at a student-run cinema club to his rise as a television commentator in At the Movies and Siskel & Ebert. Recounting the influence of the French New Wave, his friendships with Werner Herzog and Martin Scorsese, as well as travels to Sweden and Rome to visit Ingrid Bergman and Federico Fellini, Ebert never loses sight of film as a key component of our cultural identity. In considering the ethics of film criticism—why we should take all film seriously, without prejudgment or condescension—he argues that film critics ought always to engage in open-minded dialogue with a movie. Extending this to his accompanying selection of “10 Bests,” he reminds us that hearts and minds—and even rankings—are bound to change.

***

To read more about books by Roger Ebert published by the University of Chicago Press, click here.

***

The University of Chicago Press is pleased to announce that House of Debt: How They (and You) Caused the Great Recession and How We Can Prevent It from Happening Again, by Amir Sufi and Atif Mian, has been awarded the 2016 Gordon J. Laing Prize. The prize was announced during a reception on April 21st at the University of Chicago Quadrangle Club. The Gordon J. Laing Prize is awarded annually by the University of Chicago Press to the faculty author, editor, or translator of a book published in the previous three years that has brought the greatest distinction to the Press’s list. Books published in 2013 or 2014 were eligible for this year’s award. The prize is named in honor of the scholar who, serving as general editor from 1909 until 1940, firmly established the character and reputation of the University of Chicago Press as the premier academic publisher in the United States.

Taking a close look at the financial crisis and housing bust of 2008, House of Debt digs deep into economic data to show that it wasn’t the banks themselves that caused the crisis to be so bad—it was an incredible increase in household debt in the years leading up to it that, when the crisis hit, led consumers to dramatically pull back on their spending. Understanding those underlying causes, the authors argue, is key to figuring out not only exactly how the crisis happened, but how we can prevent its recurrence in the future.

Originally published in hardcover in May 2014, the book has received extensive praise in such publications as the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Financial Times, Economist, New York Review of Books, and other outlets.

Amir Sufi is the Chicago Board of Trade Professor of Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Atif Mian is the Theodore A. Wells ’29 Professor of Economics at Princeton University and director of the Julis-Rabinowitz Center for Public Policy and Finance.

The Press is delighted to name Professor Sufi to a distinguished list of previous University of Chicago faculty recipients that includes Adrian Johns, Robert Richards, Martha Feldman, Bernard E. Harcourt, Philip Gossett, W. J. T. Mitchell, and many more.

To read more about House of Debt, click here.

Raymond and Lorna Coppinger have long been acknowledged as two of our foremost experts on canine behavior—a power couple for helping us to understand the nature of dogs, our attachments to them, and how genetic heritage, environmental conditions, and social construction govern our understanding of what a dog is and why it matters so much to us.

In a profile of their latest book What Is a Dog?, the New York Times articulates what’s at stake in the Coppingers’ nearly four decades of research:

Add them up, all the pet dogs on the planet, and you get about 250 million.

But there are about a billion dogs on Earth, according to some estimates. The other 750 million don’t have flea collars. And they certainly don’t have humans who take them for walks and pick up their feces. They are called village dogs, street dogs and free-breeding dogs, among other things, and they haunt the garbage dumps and neighborhoods of most of the world.

In their new book, “What Is a Dog?,” Raymond and Lorna Coppinger argue that if you really want to understand the nature of dogs, you need to know these other animals. The vast majority are not strays or lost pets, the Coppingers say, but rather superbly adapted scavengers — the closest living things to the dogs that first emerged thousands of years ago.

Other scientists disagree about the genetics of the dogs, but acknowledge that three-quarters of a billion dogs are well worth studying.

The Coppingers have been major figures in canine science for decades. Raymond Coppinger was one of the founding professors at Hampshire College in Amherst, and he and Lorna, a biologist and science writer, have done groundbreaking work on sled dogs, herding dogs, sheep-guarding dogs, and the origin and evolution of dogs.

“We’ve done everything together,” he said recently as they sat on the porch of the house they built, set on about 100 acres of land, and talked at length about dogs, village and otherwise, and the roots of their deep interest in the animals.

To read the profile—which touches on the Coppingers’ nuanced history with wild canines—in full, click here.

To read more about What Is a Dog?, click here.

Jessica Riskin’s The Restless Clock: A History of the Centuries-Long Argument Over What Makes Living Things Tick explores the history of a particular principle—that the life sciences should not ascribe agency to natural phenomena—and traces its remarkable history all the way back to the seventeenth century and the automata of early modern Europe. At the same time, the book tells the story of dissenters to this precept, whose own compelling model cast living things not as passive but as active, self-making machines, in an attempt to naturalize agency rather than outsourcing it to theology’s “divine engineer.” In a recent video trailer for the book (above), Riskin explains the nuances of both sides’ arguments, and accounts for nearly 300 years worth of approaches to nature and design, tracing questions of science and agency through Descartes, Leibniz, Lamarck, Darwin, and others.

From a review at Times Higher Ed:

The Restless Clock is a sweeping survey of the search for answers to the mystery of life. It begins with medieval automata – muttering mechanical Christs, devils rolling their eyes, cherubs “deliberately” aiming water jets at unsuspecting visitors who, in a still-mystical and religious era, half-believe that these contraptions are alive. Then come the Enlightenment android-builders and philosophers, Romantic poet-scientists, evolutionists, roboticists, geneticists, molecular biologists and more: a brilliant cast of thousands fills this encyclopedic account of the competing ideas that shaped the sciences of life and artificial intelligence.

A profile at The Human Evolution Blog:

To understand this unspoken arrangement between science and theology, you must first consider that the founding model of modern science, established during the Scientific Revolution of the seventeenth century, assumed and indeed relied upon the existence of a supernatural God. The founders of modern science, including people such as René Descartes, Isaac Newton and Robert Boyle, described the world as a machine, like a great clock, whose parts were made of inert matter, moving only when set in motion by some external (divine) force.

These thinkers insisted that one could not explain the movements of the great clock of nature by ascribing desires or tendencies or willful actions to its parts. That was against the rules. They banished any form of agency – purposeful or willful action – from nature’s machinery and from natural science. In so doing, they gave a monopoly on agency to an external god, leaving behind a fundamentally passive natural world. Henceforth, science would describe the passive machinery of nature, while questions of meaning, purpose and agency would be the province of theology.

And a piece at Library Journal:

The work of luminaries such as René Descartes, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Immanuel Kant, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, and Charles Darwin is discussed, as well as that of contemporaries including Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins, and Stephen Jay Gould. But there are also the lesser knowns: the clockmakers, court mechanics, artisans, and their fantastic assortment of gadgets, automata, and androids that stood as models for the nascent life sciences. Riskin’s accounts of these automata will come as a revelation to many readers, as she traces their history from late medieval, early Renaissance clock- and organ-driven devils and muttering Christs in churches to the robots of the post-World War II era. Fascinating on many levels, this book is accessible enough for a science-minded lay audience yet useful for students and scholars.

To read more about The Restless Clock, click here.

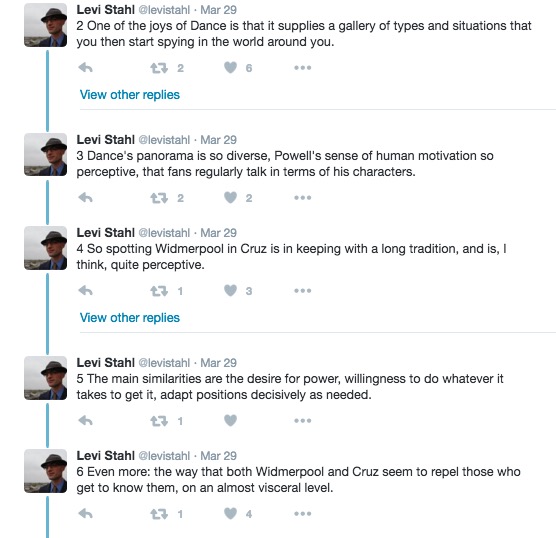

For those of you who missed it, here is Levi Stahl’s 31-part Twitter essay from late last week, which responds to an op-ed in the New York Times by columnist Ross Douthat comparing Republican presidential candidate Ted Cruz to Widmerpool, the anti-anti-hero from Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time:

To read more about A Dance to the Music of Time, click here.

To commemorate the third anniversary of Roger Ebert’s death, we asked UCP film studies editor Rodney Powell to consider his legacy. Read after the jump below.

***

It’s three years since Roger Ebert’s death; for three years we’ve been deprived of his reviews, “Great Movies” essays, and journal entries. Fortunately most of his writing remains available online, and the University of Chicago Press has been privileged to publish three of his books—Awake in the Dark, Scorsese by Ebert, and The Great Movies III, with a fourth, a reprint of Two Weeks in the Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook just out. And there’s more to come, with The Great Movies IV due this fall.

So I think this should be an occasion for celebrating rather than lamenting. My own hope is that, as the celebrity status he attained fades from memory, he will be recognized for the brilliant writer he was. Within the confines of the shorter forms in which he wrote, he was an absolute master. Of course not every piece was at the same high level, but a remarkable percentage of his vast output will, I think, stand the test of time. Here I will only mention the high regard in which his work is held by film scholar extraordinaire David Bordwell (see his Forewords to Awake and GM III) as additional proof of its value.

I provided my own brief appreciation of Ebert’s writing back in 2013, and I still agree with that appraisal, particularly this statement: “Like other lasting critics, he could make his readers understand the moral qualities of the works he valued most by revealing how they made audiences think about the Big Questions—not by preaching, but by engaging with the dramatic complexities at the core of those films.”

And I don’t think I can do any better than the final paragraph of that piece: “If writers give us the best of themselves in their writing, Ebert’s gifts to his readers were abundant—intelligence, wit, clarity, and generosity expressed in prose that is both engaging and thought-provoking. As long as the printed word survives, those gifts of his large spirit will be available. And death shall have no dominion.”

Amen.

To read more about books by Roger Ebert published by the University of Chicago Press, click here.

The Essential Paul Laffoley: Works from the Boston Visionary Cell publishes this May (*super exciting*), but the meantime, here’s a teaser featuring a few of Laffoley’s paintings and video of the documentary The Mad One (Jean-Pierre Larroque/Doublethink Productions), after the jump.

***

Cosmolux, 1981. Oil, acrylic, and lettering on canvas. 73 1/2 x 73 1/2 in. © Paul Laffoley.

The Living Klein Bottle House of Time, 1978. Oil, acrylic, and lettering on canvas. 73 1/2 x 73 1/2 in. © Paul Laffoley.

Geochronmechane: Time Machine from the Earth, 1990. Serigraph on rag paper. Edition of 75. 28 in. x 28 in. © Paul Laffoley.

To read more about The Essential Paul Laffoley, click here.

From Time‘s slightly soiled (c/o a surprise appearance by Evelyn Waugh) list of the 100 Most-Read Female Writers on College Campuses:

Toni Morrison and Jane Austen are among the most-read female writers on college campuses, a new TIME analysis found.

First place on the list—which is based on 1.1 million college syllabi collected by the Open Syllabus Project—goes to Kate L. Turabian for her Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations, assigned in 3,998 classrooms over the last 15 years.

Though much coverage of Time‘s list skewed toward questioning how Waugh’s inclusion made it so far along in the editing process (he clocked in at number 97), some blogs did point out that Turabian, while securing the top spot based on her gender affiliation at #17 overall, was still surpassed by 16 male-identified writers on a general ranking of syllabi (with Shakespeare, Plato, and Freud finishing near the top), rather unfortunately (and sadly, not all that surprisingly) leaving woman-identified writers completely out of the top ten.

Read more about all things Turabian here.

Read Time’s list in full here.

Sociologist Jonathan R. Wynn went live in the Guardian last week with piece coincident with the 29th annual SXSW Festival in Austin, Texas—in which he articulated the role festivals like SXSW play in urban infrastructure, as they replace previously staid (and spatially permanent) cultural institutions, all the while playing an increasingly major socioeconomic role, especially in terms of gentrification and symbolic impact. All of this draws on the research behind Wynn’s recent book Music/City, which considers the expansive and shifting roles played by these kind of festivals in contemporary urban and cultural life. In a brief excerpt from the Guardian piece below, he explores how previous mayor Will Wynn’s strategy of nurturing SXSW as a crucial part of the city’s downtown development played out of the course of several years:

There are direct and indirect costs and benefits to Wynn’s strategy. While Austin’s downtown has seen robust growth, its inner core has gentrified, homeownership has risen well above the city’s median income, and the city’s poor have moved to Austin’s outer ring.

Downtown condo, hotel and residential growth has boomed. When I returned to the Mohawk two years later, for example, I saw that the onetime dirt lot across the street had transformed into a 120-unit luxury apartment complex called The Beverly.

At the same time, musicians and other creatives feel they have become victims of the successes they played a part in. Musicians and venue owners claim they aren’t seeing the benefits of Austin’s boom. In 2011, the owner of Emo’s and co-owner of Antone’s – two downtown Austin standbys – felt the pressures of these changes, evoking the gentrification of New York’s East Village to claim his venues were priced out of the downtown core, telling Billboard: “We were going the way of CBGB.” Perhaps more vitally, Austin’s downtown has grown, but it has also become richer, and whiter. A team of sociologists from the University of Texas at Austin have tracked the multiple effects of these economic changes for those on the bottom of the socio-economic ladder in Invisible in Austin: Life and Labor in an American City.

Austin is the model of a Music City. As the mayors of cities like Phoenix, Portland, and Kansas City leave SXSW after their “secret” meeting on Stem-fueled (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math ) economic development, they should learn from Austin’s events-based cultural policy as well. Festivals can be the foundation of a low risk urban cultural policy with long-term rewards, including promoting arts education, developing local media, stimulating tourism development and crystallizing a city identity. But these urban cultural policies need to be held to a high standard. They must attract capital to a city while also maintaining an economic and symbolic responsibility to its local communities.

As the 29th SXSW kicks off this week, the Music City will be on full display, hitting both high notes and low. Festivals will increasingly be a part of our city culture. Just as the first SXSW was designed to be a showpiece for Austin talent, these large-scale events can and should maintain that commitment to their localities.

To read Wynn in full at the Guardian, click here.

To read more about Music/City, click here.

In timely coincidence with today’s primaries and the book’s return to print, The Last Hurrah by Edwin O’Connor received some well-tailored praise from Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist David Hall, writing in the Columbia Daily Herald, who suggests we:

Take a breather from the daily pounding of politics and reflect: chaos, confusion, and gutter campaigning are not new. . . . Even today’s politics are not speeding away. We have survived travail through democracy. Good and thoughtful fiction lets us pause and reflect.

Honing in on The Last Hurrah, an almost-story adapted from the life of notorious Boston mayor James Michael Curley, he writes of the book’s foreboding about the nature of the relationship between media and politics:

Another poignant tale of American politics is The Last Hurrah by Edwin O’Connor. Set in an old and mainline northeastern city, the novel examines the dying days of machine politics when largess held voters in sway. Frank Skeffington, 72, believes he is entitled to one more term. His political compass loses its bearing against a young, charismatic challenger, void of political experience but adorned with war medals and good looks. O’Connor’s 1956 novel was prescient in portraying the impact television would have on politics. While The Last Hurrah lacks the intellectual complexity of All the King’s Men, it raises good questions about how religion, ethnicity, class and economics foster into political alliance—questions still relevant starting even at the city and county level.

To read more about The Last Hurrah, click here.

A free chapter from Sixteen for ’16: A Progressive Agenda for a Better America

by Salvatore Babones (Policy Press)

***

Back in the good old days, that is to say the mid-1990s, taxpayers with annual incomes over $500,000 paid federal income taxes at an average effective rate of 30.4%. For 2012, the latest year for which data are available, the equivalent figure was 22.0%.

The much-ballyhooed January 1, 2013 tax deal that made the Bush-era tax cuts permanent for all except the very well-off will do little to reverse this trend: The deal that passed Congress only restores pre-Bush rates on the last few dollars of earned income, not on the majority of earned income, on corporate dividends, or on most investment gains.

Someone has had a very big tax cut in recent years, and the chances are that someone is not you. In the 1990s taxes on high incomes were already low by historical standards. Today, they are even lower. The super-rich are able to lower their taxes even further through a multitude of tax minimization and tax avoidance strategies.

The very tax system itself has in many ways been structured to meet the needs of the super-rich, resulting in a wide variety of situations in which people can multiply their fortunes without actually having to pay tax. In general, it is also much easier to hide income when most of your income comes from investments than when your income is reported on regular W-2 statements from your employer direct to the IRS.

Whatever our tax statistics say about the tax rates of the super-rich, we can be sure they are lower in reality. At the same time that their tax rates are going down, the annual incomes of highly paid Americans are going through the roof.

In the 1990s the average income of the top 0.1% of American taxpayers was around $3.6 million. In 2012 it was nearly $6.4 million.6 And yes, these figures have been adjusted for inflation. Thanks to the careful database work of Capital in the Twenty-First Century author Thomas Piketty and his colleagues, it is now relatively easy to track and compare the incomes of the top 1%, 0.1%, and 0.01%. The historical comparisons don’t make for pretty reading.

Forget the merely well-off 1%. In the 21st century the top 0.1% of American households have consistently taken home more than 10% of all the income in the country, up from 3% in the 1970s.7 And these figures only include realized income: that is to say, income booked and reported to the tax authorities. If you own a company that doubles in value but you don’t sell any shares, you don’t have any income. Ditto land, buildings, airplanes, yachts, artwork, coins, stamps, etc.

High inequality plus low taxes equals fiscal crisis. The rich are taking more and more money out of the economy, but they are not returning it in the form of taxes. The result is that the US government no longer has the resources it needs to properly govern the country. The country needs universal preschool, universal healthcare, and a massive government-sponsored jobs program. The country needs a complete renewal of its crumbling human and physical infrastructure. The country needs funds for everything from the cleanup of atomic waste in Hanford, Washington to improvements at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. And the country needs higher taxes on today’s higher incomes to pay for it all.

In 2010 the United States government collected a smaller proportion of the nation’s total national income in income taxes than at any time since 1950.8 That figure has since rebounded, but it is still well below the average from 1996-2001. Under current law the federal income tax take is projected to rise from the historic low of 6.1% in 2010 to 8.6% of national income in 2016. This is an improvement over recent years, but it is still far below the average of 9.5% for the years 1998-2001, the last time the federal government actually ran a budget surplus.

The top marginal tax rate on the highest incomes is now 39.6%, as it was in the 1990s. This is still a far cry from the 50% top tax bracket of the 1970s or the 70% top tax bracket of the 1960s, never mind the 91-92% top tax brackets of the 1950s.10 The return to 1990s levels is a good start, but the next President should push to go much farther back because the tax system has been moving in the wrong direction for a very long time. High incomes are much higher than they ever were and people with high incomes pay much less tax than at almost any time in our modern history. The result, unsurprisingly, has been the enormous concentration of income among a small, powerful elite documented by Piketty in Capital in the Twenty-First Century but no less obvious for all to see.

The concentration of income among a powerful elite may be very good for members of that elite, but it is bad for our society, bad for our democracy, and even bad for our economy. Socially, highly concentrated incomes undermine our national institutions and warp our way of life. For example, people who can afford to send their children to exclusive private schools cease to care for the health of public education, or they erect barriers to separate “their” public schools from everyone else’s public schools. Similarly, people who can afford the very best private healthcare care little about ensuring high-quality public healthcare. People who fly private jets care little about congestion at public airports. People who drink imported bottled water care little about the poisoning of rivers and underground aquifers. Enormous differences in income inevitably create enormous distances between people. The United States is starting to resemble the fractured societies of Africa and Latin America, where the rich live in ated “communities” with armed guards who enforce the exclusion of the lower classes—except to allow them entry as maids and gardeners.

These nefarious effects of inequality can already be seen in America’s sunbelt cities, where there are fine gradations of gated communities: armed guards for the super-rich, unarmed guards for the merely well- off, keypad security for the middle class, and on down the line to the unprotected poor. We should be ashamed, one and all.

Politically, highly concentrated incomes threaten the integrity of American democracy by fostering corruption of all kinds. When the income differences between regulators and the industries they regulate are small, we can count on regulators to look after our interests.

But when industry executives make two or three (or ten) times as much as regulators, it is almost impossible to prevent corruption. Even where there is no outright corruption, it is impossible for regulators to retain talented staff. People will take modest income cuts to work in secure public sector employment. They will not take massive income cuts. Those who do are often just doing a few years on the inside so they can better evade regulation when they go back to the private sector. When doing a few years on the inside includes serving in Congress merely as way to get a high-paying job as a lobbyist, we are in serious trouble.

Along with highly concentrated incomes come vote buying and voter suppression. When the stakes are so high, people will play dirty. No one knows how many local boards of one kind or another around the country have been captured by local economic interests, but the number must be very large.

Economically, highly concentrated incomes ensconce economic privilege, suppress intergenerational mobility, and can ultimately lead to the total breakdown of the free market as a system for effi driving production and consumption decisions. Privilege is perpetuated by excessive incomes because with enough money the advantages of wealth overpower any amount of talent and effort on the part of those who are born poor.

Nineteenth-century English novels were obsessed with inheritance and marriage because in that incredibly unequal society birth trumped everything else. Twenty-first-century America has now reached similar levels of income concentration among a powerful elite. To make this point graphically clear, a family with a billion-dollar fortune that does absolutely no planning to avoid the 40% tax on large estates and no paid work whatsoever can comfortably take out $15 million a year to live on (after taxes, adjusted for inflation) in perpetuity until the end of history—while still growing the estate. That’s how mind-bogglingly large a billion-dollar fortune is.

But probably the least recognized impact of high inequality on our economy is that it severely impairs the efficient operation of the free market itself. Market pricing is at its core a mechanism for rationing. The market directs limited resources to the places where they command the highest prices. The basic idea of rationing by price is that prices encourage people to carefully weigh their purchases against each other—in other words, to economize.

In an economy where everyone earns roughly the same income, rationing by price works just fine for most goods. People take care of their necessities first. Then they can choose whether to spend their extra money on eating out, taking vacations, renovating their homes, or saving up to buy something big like a boat. Because all of these goods are priced in the same currency, people can directly compare their values against each other. And if everyone has roughly the same amount of money to spend, market prices represent roughly the same values for different people. If you and I have the same income, a $20 restaurant meal means as much to me as it does to you.

Problems set in when incomes are very unequal. For people with extraordinarily high incomes, prices become meaningless. What does a $20 restaurant meal mean to someone who makes $20 million a year? Nothing.

The result is incredible waste as the market economy no longer forces people to economize. When rich people accumulate dozens of cars, maintain yachts they only use once a year, or have servants order fresh-cut flowers every day for houses they rarely visit, they are wasting resources that could be put to much better use by other people. Waste like this invalidates the foundational principle of modern economics: that the market maximizes the total utility of society.

That principle only holds if a dollar has the same meaning for you as it does for me. Highly concentrated incomes undermine the whole idea of the market as an economy—that is, as something that economizes. And that is the strongest argument for much higher taxes on higher incomes. There are many ways to reduce inequality, but the simplest and most efficient way is through taxation. The goal of income taxes should be to tilt the field so that earning an after-tax dollar means just as much to a CEO as to a fast food worker. That’s why a 90% marginal tax on incomes over a million dollars is entirely appropriate.

For a poor person who pays no income tax, a $20 restaurant meal costs $20. That person must make a real sacrifice to eat out. For a CEO with a 90% marginal tax rate, a $20 restaurant meal costs $200 in before-tax income. That may not be a huge sacrifice for someone who makes several million dollars a year, but it does change the equation. A CEO may not hesitate to eat out, but may hesitate to buy a private jet when flying business class will suffice.

To be sure, we need higher taxes on higher incomes to raise money for government. But we also need higher taxes on higher incomes just to make the economy work properly. That’s why the economy worked so much better in the high-tax 1950s and 1960s than it has since.

The ultimate goal of income taxes should be to make money as meaningful to a millionaire as it is to you or me. If we can’t quite get there in the next few years, we can certainly get closer than we are. One of President Obama’s most important accomplishments has been to set us on the path toward economic sanity by raising taxes on the highest incomes. The next President should build on this legacy—and in a big way.

***

Salvatore Babones is associate professor of sociology and social policy at the University of Sydney.

To read more about Sixteen for ’16, click here.

Photo by: Ariel Uribe for the Chicago Maroon.

Full of “blood and thunder“—words for the Lyric Opera of Chicago’s staging of Giuseppe Verdi’s Nabucco, an amalgamation of quasi-stories from the Book of Jeremiah and the Book of Daniel coalesced around a love triangle, here revived for the first time since 1998. On the heels of its opening—the full run is from January 23 to February 12—UCP hosted a talk and dinner featuring a lecture “Nabucco and the Verdi Edition” by Francesco Ives. That Verdi Edition, The Works of Giuseppe Verdi, is the most comprehensive critical edition of the composer’s works. In addition to publishing its many volumes, the University of Chicago Press also hosts a website devoted to all aspects of the project, which you can visit here; to do justice to the scope and necessity of the Verdi Edition, here’s an excerpt from “Why a Critical Edition?” on that same site:

The need for a new edition of Verdi’s works is intimately tied to the history of earlier publications of the operas and other compositions. When Verdi completed the autograph orchestral manuscript of an opera, manuscript copies were made by the theater that commissioned the work or by his publisher (usually Casa Ricordi). These copies were used in performance, and most of the autograph scores became part of the Ricordi archives. Copies of the copies were made, and orchestral materials were extracted for performances. With the possible exception of his last operas, Otello and Falstaff, Verdi played no part whatever in preparing the printed scores: almost all printed editions of his works were prepared by Ricordi after Verdi’s death in 1901.

Predictably, these copying and printing practices have yielded vocal and orchestral parts that differ drastically from the autograph scores. Indeed, the problem of operas performed using unreliable parts and scores dates to Verdi’s own lifetime. After the premieres of Rigoletto, Il trovatore, and La traviata, for example, Verdi wrote to Ricordi on 24 October 1855: “I complain bitterly of the editions of my last operas, made with such little care, and filled with an infinite number of errors.”

Copyists and musicians who prepared these errant printed editions were not consciously falsifying Verdi’s text. They merely glossed over particularities of Verdi’s notation (e.g., the simultaneous use of different dynamic levels—“p” and “pp”, for instance) and altered details of his orchestration, which differed considerably from the style of Puccini, whose music dominated Italian opera when the printed editions of Verdi’s works were prepared. These editions, which in certain details drastically compromise the composer’s original text, are the scores that are used today, except where the critical edition has made reliable scores available.

The critical edition of the complete works of Verdi undertaken jointly by the University of Chicago Press and Casa Ricordi is finally correcting this situation.

To read more about The Works of Giuseppe Verdi, click here.

To visit the project’s website, click here.

Our free e-book for February:

Peter Bacon Hales’s Outside the Gates of Eden: The Dream of America from Hiroshima to Now

Download your copy here.

***

Exhilaration and anxiety, the yearning for community and the quest for identity: these shared, contradictory feelings course through Outside the Gates of Eden, Peter Bacon Hales’s ambitious and intoxicating new history of America from the atomic age to the virtual age.

Born under the shadow of the bomb, with little security but the cold comfort of duck-and-cover, the postwar generations lived through—and led—some of the most momentous changes in all of American history. Hales explores those decades through perceptive accounts of a succession of resonant moments, spaces, and artifacts of everyday life—drawing unexpected connections and tracing the intertwined undercurrents of promise and peril. From sharp analyses of newsreels of the first atomic bomb tests and the invention of a new ideal American life in Levittown; from the music emerging from the Brill Building and the Beach Boys, and a brilliant account of Bob Dylan’s transformations; from the painful failures of communes and the breathtaking utopian potential of the early days of the digital age, Hales reveals a nation, and a dream, in transition, as a new generation began to make its mark on the world it was inheriting.

Full of richly drawn set-pieces and countless stories of unforgettable moments, Outside the Gates of Eden is the most comprehensive account yet of the baby boomers, their parents, and their children, as seen through the places they built, the music and movies and shows they loved, and the battles they fought to define their nation, their culture, and their place in what remains a fragile and dangerous world.

To read more about Outside the Gates of Eden, click here.

The University of Chicago Press: you’ve got the answer(s), we’ve got the question(s).

(And by questions, I mean Dave Hickey’s other books.)

To read more about The Invisible Dragon, click here.

To read more about 25 Women: Essays on Their Art, click here.

Just a snippet from a fab piece by Jennifer Tyburczy for Artforum on the research informing her recent book Sex Museums: The Politics and Performance of Display, which places the museum in its spatial, political, and sexual contexts, each imbricated by the other, as well as our notions of public and private. You can read more from her “500 Words” piece here.

***

The big surprise, though, was that as soon as I started to write about sex museums, they started to close. The latter part of my book is dedicated to an ethnography of these spaces. It was disconcerting when I would plan out a visit to Los Angeles to see an erotic museum that then closed mere months before I could make the trip. Part of the book became about the failure of these ventures, and I don’t mean in a Jack Halberstam, Queer Art of Failure kind of way. Ultimately, many of these museums could not provide what visitors wanted, which was a really raw experience with sex drawn from the archive and arranged in displays. A lot of the museums I discuss—whether in New York, Denmark, or Spain—had an ingrained idea of who their normative visitor was and where their threshold of shock was located. Without fail, they always set the bar too low. People wanted more! The demands of being a twenty-first-century museum taking on the onus to display sex overwhelmed a lot of the museum planners. Typically they censored themselves in some way that visitors noted. The heartening message here is that we shouldn’t assume that people will be shocked and turned off by displays of diverse sexual cultures and people. Museum visitors are smart and savvy, and ready and willing to have that experience. My work makes an argument for the emotional and sexual intelligence of a viewer.

To read more about Sex Museums, click here.

From a recent review of Michael Taussig’s The Corn Wolf at Pop Matters:

Taussig’s work is the sort of bewilderingly beautiful prose (one is often tempted to call it poetry) that’s able to operate on multiple intellectual levels. The first essay in the collection, “The Corn Wolf: Writing Apotropaic Texts”, immerses the reader fully and mercilessly in the style. It opens with a poor graduate student realizing that writing up their fieldwork is the most difficult and important task of graduate school, and also the one thing graduate school teaches you nothing about. Fieldwork and writing; “they are both rich, ripe, secret-society-type shenanigans. Could it be that both are based on impossible-to-define talents, intuitions, tricks, and fears?”

No wonder many careerist academics dislike him.

Of course the essay isn’t so much about graduate writing as about his own writing, and about the act of writing—the magical act of writing—itself.

For example, Taussig considers anthropology’s treatment of magic and shamanic sorcery: “Pulling the wool over one’s eyes is a simpler way of putting it… What we have generally done in anthropology is really pretty amazing in this regard, piggybacking on their magic and on their conjuring—their tricks—so as to come up with explanations that seem nonmagical and free of trickery.”

This seemingly nonmagical academic form of writing—or mode of production, as he calls it—is what he refers to as ‘agribusiness writing’: “Agribusiness writing is what we find throughout the university and everyone knows it when they don’t see it.” Against it he pitches the idea of ‘apotropaic writing’, a magic that connives with the prosaic to produce a counter-magic of its own.

When anthropologists demystify shamanic sorcery, for instance, the ‘wolfing’ moves of apotropaic magic would reveal the sorcery implicit in the act of the ‘scientific’ anthropologist’s recasting of shamanism. Indeed, the fact that the wonder and magic of the everyday world has been demystified by science is a sort of magical transformation itself. Is this how we re-enchant the world? By the use of story-telling and writing to re-position what seems like the boring, unmagical workaday world of everyday capitalist drudgery and expose it as the magical sleight-of-hand and tricksterism that it is? “I have long felt that agribusiness writing is more magical than magic ever could be and that what is required is to counter the purported realism of agribusiness writing with apotropaic writing as countermagic, apotropaic from the ancient Greek meaning the use of magic to protect one from harmful magic.”

To read more about The Corn Wolf, click here.

To read the Pop Matters review in full, click here.

The Party Decides: Presidential Nominations Before and After Reform is having quite a week—and quite an election season, in general. The book was adopted early by Nate Silver at his FiveThirtyEight blog, which led to explorations of its hypothesis here and here, and most recently here: where Silver posits the book as the most “misunderstood” of the 2016 primary season.