new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Dennis Baron, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 37

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Dennis Baron in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: SoniaT,

on 5/7/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

A Better Pencil: Readers,

and the Digital Revolution,

digital content providers,

digital rights ebooks,

ebook licensing agreements,

Ebook Rules,

Ebooks law,

Books,

Law,

Technology,

writers,

Media,

publishing law,

Web of Language,

Dennis Baron,

*Featured,

Add a tag

I love ebooks. Despite their unimaginative page design, monotonous fonts, curious approach to hyphenation, and clunky annotation utilities, they’re convenient and easy on my aging eyes. But I wish they didn’t come wrapped in legalese. Whenever I read a book on my iPad, for example, I have tacitly agreed to the 15,000-word statement of terms and conditions for the iTunes store. It’s written by lawyers in language so dense and tedious it seems designed not to be read, except by other lawyers, and that’s odd, since these Terms of Service agreements (TOS) concern the use of books that are designed to be read.

The post What if printed books went by ebook rules? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 12/5/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

english language,

endangered languages,

Rick Perry,

American English,

Web of Language,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Michelle Bachmann,

CEPI,

english speakers,

Čepi,

US,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

There are roughly 7,000 languages spoken around the globe today. Five hundred years ago there were twice as many, but the rate of language death is accelerating. With languages disappearing at the rate of one every two weeks, in ninety years half of today’s languages will be gone.

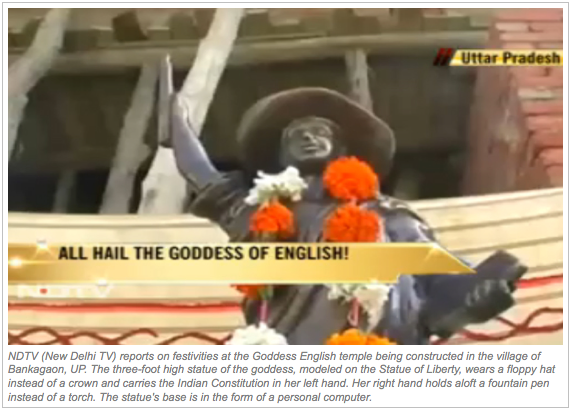

Mostly it’s the little languages, those with very few speakers, that are dying out, but language death can hit big languages as well as little and mid-sized ones. And it can hit those big languages pretty hard. Sure, languages like Degere and Vuna are disappearing in Kenya, Jeju in Korea, Manchu in China. And sure, Nigerians complain that Yoruba is fast giving way to English. But language-watchers warn that English itself may have entered a steep and potentially irreversible decline in both its native and its adoptive country.

English, having spread as a global language during the 20th century, has now become so thin on the ground back home that it’s in danger of disappearing. That’s the conclusion of a new report which sees both competition from other languages and the increased ineptitude of English speakers combining to produce a catastrophic decline in the number of English speakers in England, the language’s ancestral home, as well as in the United States, where English speakers fled in search of religious liberty and alternate side of the street parking.

The report of the Center for the Study of English in the Public Interest, or ČEPI, available on that organization’s website, warns that the language could disappear in less than three generations, or perhaps they meant to say fewer? “Why should little languages like Frisian, Kashubian, and Han get all the attention?” the report asks. “Don’t the bleeding-heart anthropologists bent on preventing the inevitable realize that people stop speaking those doomed languages because other languages do the job better?” it adds. The report calls on those intent on saving endangered languages to switch their attentions to English, a language that might actually benefit from their efforts.

There’s good reason to preserve English rather than let it die. According to ČEPI director Bill Caxton, “When the last speakers go, they take with them their history and culture too.” Granted, Eskimo may not have twenty-three words for snow, as the popular myth would have it, but Eskimos do have a special relationship with snow, as evidenced by Eskimo idioms for ’snow clumped in the paws of sled dogs’ and ’snow outside the igloo that turns yellow when Morris is around.’ When Eskimo dies out, as it eventually must, that special relationship will be lost forever, and the Eskimos and the rest of the world will be left with the terms snow, slush, sleet, and snow covered with a crust of blackened automobile exhaust, hardly a vocabulary of nuance and poetry.

With the death of English, the ČEPI report notes, we’ll lose its prolific set of terms for burgers: in addition to hamburger, there’s cheeseburger, bacon burger, bacon cheeseburger, bleu cheese burger (also, blue cheese burger), quarter pounder, quarter pounder with cheese, swissburger, curry burger, tuna burger, turkey burger, chiliburger, soyburger, tofu burger, and black bean burger. And don’t forget hamburger not cooked long enough to eliminate e. coli. The wholesale loss of these terms testifying to English speakers’ preoccupation with chopped meat, and chopped meat substitutes, would be tragic.

When languages die, we also lose their secret herbal remedies and medicinal cures that could revolutionize modern medicine, their old family recipes that could turn the Food Channel on its ear. An English speaker discovered penicillin from traditional English bread mold (or mould), not to mention the extensive

By: Kirsty,

on 11/28/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Affairs,

trademark,

patent,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Occupy Wall Street,

occupy,

word occupy,

marescas,

“occupy,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

Psst, wanna buy a hot slogan?

Psst, wanna buy a hot slogan?

“Occupy Wall Street,” the protest that put “occupy” on track to become one of the 2011 words of the year, could be derailed by a Long Island couple seeking to trademark the movement’s name.

The rapidly-spreading Occupy Wall Street protests target the huge gap between rich and poor in America and elsewhere, so on Oct. 18, Robert and Diane Maresca tried to erase their own personal income gap by filing trademark application 85449710 with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office so they could start selling Occupy Wall St.™ T-shirts, bumper stickers, and totebags, as well as various other tchotchkes bearing the protest name (the Marescas’ application is for “Occupy Wall St.,” using the abbreviated form of street–they haven’t expressed an interest in owning “Occupy Wall Street” as well).

The Trademark Commission will have to decide whether anyone can own the rights to the phrase “Occupy Wall Street,” which seems to have captured the public’s imagination and entered the public domain in record time–in fact, faster than you can say “Tea Party.” If so, the Commission must then consider whether the Marescas have any right to the phrase. They didn’t join the OWS protests and they may have never even been to Wall St. (according to their application, the Marescas live in West Islip, about 50 miles from the main protest site). Plus, so far as anyone can tell, they’ve never manufactured T-shirts, bags, or stickers with “Occupy Wall St.” or any other logo or design.

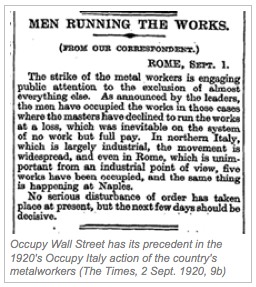

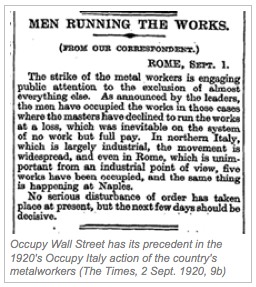

The Marescas are not the only ones trying to capitalize on the anticapitalist protests. There’s an episode of an MTV reality show, complete with commercial sponsors. There’s a book. There’s an Android app. And a company called Condomania is selling Occupy condoms (free samples available to the protestors). There are over 3,000 items of Occupy merchandise for sale on the ’net. A local pizza shop sells Occupy Meat, Occupy Veggie, and Occupy Vegan pizzas to the protestors at a discounted price of $15 a pie. There’s even an Occupy Wall Street iPhone™ app that looks like a combo of Tetris and Angry Birds ($4.99 at the iTunes™ App Store™).

The Occupy movement itself is trying to buy TV time to air a commercial that it made—though unlike the competition, the original OWS remains not-for-profit. But it’s not even clear that Occupy Wall Street could trademark its own name, or that, despite its new-found popularity, the word occupy could qualify as Word of the Year, since it’s not really a new

By: Lauren,

on 9/12/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

US,

9/11,

ground zero,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

language,

linguistics,

popular phrase,

commonly july,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

The terrorist attacks on 9/11 happened ten years ago, and although everybody remembers what they were doing at that flashbulb moment, and many aspects of our lives were changed by those attacks, from traveling to shopping to going online, one thing stands out: the only significant impact that 9/11 has had on the English language is 9/11 itself.

By: Lauren,

on 9/1/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Dictionaries,

dictionary,

back to school,

new words,

Merriam-Webster,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

added to the dictionary,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

It's back to school, and that means it's time for dictionaries to trot out their annual lists of new words. Dictionary-maker Merriam-Webster released a list of 150 words just added to its New Collegiate Dictionary for 2011, including "cougar," a middle-aged woman seeking a romantic relationship with a younger man, "boomerang child," a young adult who returns to live at home for financial reasons, and "social media" -- if you don't know what that means, then you're still living in the last century.

By: Lauren,

on 8/17/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

drgrammar,

grammar,

language,

words,

anniversary,

fun facts,

Web of Language,

Dennis Baron,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

The Web of Language is five years old today.

The first post—“Farsi Farce: Iran to deport all foreign words”—appeared on August 17, 2006, which in digital years makes it practically Neolithic. To protest American meddling in the Middle East, Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad banned all foreign words from Farsi: pizza would become “elastic bread,” and internet

By: Lauren,

on 8/5/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Dictionaries,

slang,

english,

americanisms,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

americanism,

john witherspoon,

matthew engel,

witherspoon,

treat scotticism,

engel,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

Matthew Engel is a British journalist who doesn't like Americanisms. The Financial Times columnist told BBC listeners that American English is an unstoppable force whose vile, ugly, and pointless new usages are invading England "in battalions." He warned readers of his regular FT column that American imports like truck, apartment, and movies are well on their way to ousting native lorries, flats, and films.

Engel’s tirade against the American “faze, hospitalise, heads-up, rookie, listen up” and “park up” got several million page views

By: Lauren,

on 7/28/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

internet,

Technology,

Memory,

Psychology,

Plato,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

google effect,

retest,

papyri,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

A a research report in the journal Science suggests that smartphones, along with computers, tablets, and the internet, are weakening our memories. This has implications not just for the future of quiz shows--most of us can't compete against computers on Jeopardy--but also for the way we deal with information: instead of remembering something, we remember how to look it up. Good luck with that when the internet is down.

By: Lauren,

on 7/21/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Law,

language,

New York City,

signs,

english,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Law & Politics,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

English on business signs? It's the law in New York City. According to the "true name law," passed back in 1933, the name of any store must "be publicly revealed and prominently and legibly displayed in the English language either upon a window . . . or upon a sign conspicuously placed upon the exterior of the building" (General Business Laws, Sec. 9-b, Art. 131).

Failure to comply is technically a misdemeanor, but violations

By: Lauren,

on 7/8/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

writing,

Blogs,

Media,

ebooks,

spam,

prose,

farms,

Thought Leaders,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

content farms,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

There’s a new online threat to writing. Critics of the web like to blame email, texts, and chat for killing prose. Even blogs—present company included—don’t escape their wrath. But in fact the opposite is true: thanks to computers, writing is thriving. More people are writing more than ever, and this new wave of everyone’s-an-author bodes well for the future of writing, even if not all that makes its way online is interesting or high in quality.

But two new digital developments, ebook spam and content farms, now threaten the survival of writing as we know it.

According to the Guardian, growing numbers of “authors” are churning out meaningless ebooks by harvesting sections of text from the web, licensing it for a small fee from online rights aggregators, or copying it for free from an open source like Project Gutenberg. These authors—we could call them text engineers—contribute nothing to the writing process beyond selecting passages to copy and stringing them together, or if that seems too much like work, just cutting out the original author’s name and pasting in their own. The spam ebooks that result are composed entirely of prose designed, not to convey information or send a message, but to churn profits.

The other new source of empty text is content farms, internet sweatshops where part-timers generate prose whose sole purpose is to use keywords that attract the attention of search engines. The goal of content farms is not to get relevant text in front of you, but to get you to view the paid advertising in which the otherwise meaningless words are nested.

Ebook spam and content farms may sound like the antitheses of traditional writing, in that they don’t inform, stimulate thought, or comment on the human condition. They’re certainly not the kind of repurposed writing that Wired Magazine’s Kevin Kelly foresaw back in 2006 when he wrote that we’d soon be doing with online prose what we were already doing with music: sampling, copying, remixing, and mashing up other people’s words to create our own personal textual playlists.

Kelly, who was paid for his essay, also predicted that in the brave new world of digital text the value we once assigned to words would shift to links, tags, and annotations, and that authors, no longer be paid for producing content, would once again become amateurs motivated by the burning need to share, as they now do with such abandon on Facebook and Twitter.

But if we mash up Kelly’s futuristic vision with the harsh reality that strings of keywords may bring in more dollars than connected prose, then it’s possible that tomorrow’s writers won’t be bloggers, Tweeters, or even taggers, they’ll be scrapbookers, motivated by the burning need to cut and paste. The web may be making authors of us all, but the growing number of content-free links threatens to put writing as we know it out of business.

A cynic might argue that far too many writers have already mastered the art of saying absolutely nothing, so we shouldn’t be surprised if our feverish quest to capitalize on the internet, combined with the vast expansion of the author pool that the net makes possible, have created the monster of contentless prose. We get the writing we deserve.

Plus, things online having the attraction that they do, instead of damning these new genres, soon we may be teaching students how to master them. After all, no writing course is considered complete without a unit on how to write effective email. So it won’t be long before some start-up offers a course in text-mashing instaprose. Or an

By: Lauren,

on 6/27/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Constitution,

Dictionaries,

dictionary,

supreme court,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Law & Politics,

chief justice,

courtroom,

John G. Roberts Jr.,

legal terms,

justices,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

The Supreme Court is using dictionaries to interpret the Constitution. Both conservative justices, who believe the Constitution means today exactly what the Framers meant in the 18th century, and liberal ones, who see the Constitution as a living, breathing document changing with the times, are turning to dictionaries more than ever to interpret our laws: a new report shows that the justices have looked up almost 300 words or phrases in the past decade. Earlier this month, according to the New York Times, Chief Justice Roberts consulted five dictionaries for a single case.

Even though judicial dictionary look-ups are on the rise, the Court has never commented on how or why dictionary definitions play a role in Constitutional decisions. That’s further complicated by the fact that dictionaries aren’t designed to be legal authorities, or even authorities on language, though many people, including the justices of the Supreme Court, think of them that way. What dictionaries are, instead, are records of how some speakers and writers have used words. Dictionaries don’t include all the words there are, and except for an occasional usage note, they don’t tell us what to do with the words they do record. Although we often say, “The dictionary says…,” there are many dictionaries, and they don’t always agree.

As for the justices, they aren’t just looking up technical terms like battery, lien, and prima facie, words which any lawyer should know by heart. They’re also checking ordinary words like also, if, now, and even ambiguous. One of the words Chief Justice Roberts looked up last week in a patent case was of. These are words whose meanings even the average person might consider beyond dispute.

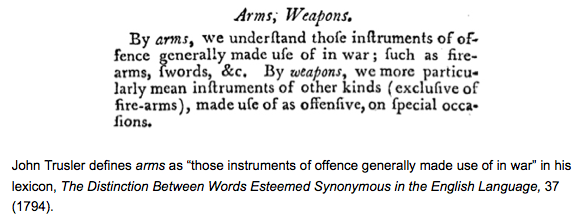

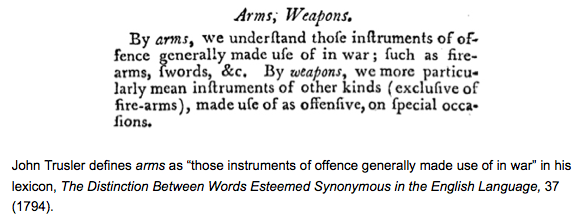

Sometimes dictionary definitions inform landmark decisions. In Washington, DC, v. Heller (2008), the case in which the high Court decided the meaning of the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms, both Justice Scalia and Justice Stevens checked the dictionary definition of arms. Along with the dictionaries of Samuel Johnson and Noah Webster, Justice Scalia cited Timothy Cunningham’s New and Complete Law Dictionary (1771), where arms is defined as “any thing that a man wears for his defence, or takes into his hands, or useth in wrath to cast at or strike another” (variations on this definition occur in English legal texts going back to the 16th century). And Justice Stevens cited both Samuel Johnson’s definition of arms as “weapons of offence, or armour of defence” (1755) and John Trusler’s “by arms, we understand those instruments of offence generally made use of in war; such as firearms, swords, &c.” (1794).

The much less publicized case of Barnhart v. Peabody Coal Co. (2003) turned in part on the meaning of a single word, shall. In this case the justices all agreed that the word shall in one particular section of the federal Coal Act functions as a command. What they disagreed about was just how much latitude the use of shall permits.

In Peabody Coal the Court’s majority decided that s

By: Lauren,

on 6/14/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

commas,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Constitution,

writing,

Education,

grammar,

punctuation,

comma,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

A rant in Salon by Kim Brooks complains, “My college students don’t understand commas, far less how to write an essay,” and asks the perennial question, “Is it time to rethink how we teach?”

While it’s always time to rethink how we teach, teaching commas won’t help.

Teachers like Brooks commonly elevate the lowly comma to a position of singular importance. But documents in which a misplaced comma can mean life or death, or at least the difference between a straightforward contract and a legal nightmare of Bleak House proportions, are myths, just like the myth that says Eskimo has twenty-three words for snow (twenty-eight? forty-five?). More to the point: understanding commas does not guarantee competent writing.

As for comma misuse, well, just look no further than the United States Constitution. Originalists see every word and punctuation mark of that founding document as evidence of the Framers’ intent. Constitutional commas set off syntactic units or separate items in a list, just as we do today (though don’t look for consistency of punctuation in the Constitution: sometimes there’s a comma before the last item in a list, and sometimes there isn’t). But what does the good-writers-understand-commas crowd make of the fact that the Framers and their eighteenth-century peers also used commas to indicate pauses for breath, to cover up drips from the quill pens they used for writing, or like some college students today, for no apparent reason at all?

Take, for example, the comma dividing adjective from noun in this excerpt from Article I, sec. 9:

No Capitation, or other direct, Tax shall be laid . . .

Or this one from Art. II, sec. 1, separating direct from indirect object:

The President shall, at stated Times, receive for his Services, a Compensation . . .

We don’t separate the subject from the verb with a comma, except in the Constitution:

Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. [Art. III, sec. 3]

Or the first and third commas of the Second Amendment:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Any student turning in essays with commas like those would be marked wrong.

Plus a contemporary writing teacher would spill a lot of red ink correcting all those unnecessary capital letters in the Constitution, and the jarring it’s for its in Art. I, sec. 9—because no one but “students who can’t write” would use them today:

No State shall, without the Consent of the Congress, lay any Imposts or Duties on Imports or Exports, except what may be absolutely necessary for executing it’s inspection Laws. [emphasis added]

Oh, and don’t forget that the Framers wrote chuse for choose (more red ink: they did this six times), or that little problem with pronoun agreement in Article I, sec. 5, where each House is both an its and a the

By: Lauren,

on 5/5/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Technology,

computers,

computer,

alan turing,

artificial intelligence,

Flight of the Conchords,

Dennis Baron,

ai,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

computer brain,

computers take over the world,

loebner,

turing,

contestants,

medal,

contest,

science fiction,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

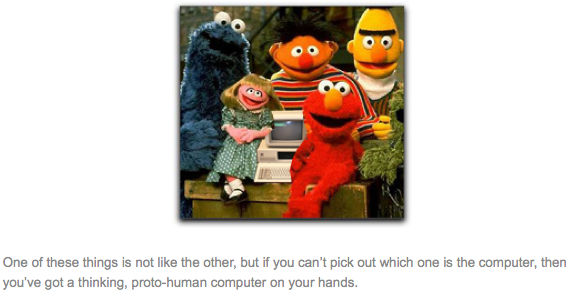

Each year there’s a contest at the University of Exeter to find the most human computer. Not the computer that looks most like you and me, or the computer that can beat all comers on Jeopardy, but the one that can convince you that you’re talking to another human being instead of a machine.

Each year there’s a contest at the University of Exeter to find the most human computer. Not the computer that looks most like you and me, or the computer that can beat all comers on Jeopardy, but the one that can convince you that you’re talking to another human being instead of a machine.

To be considered most human, the computer has to pass a Turing test, named after the British mathematician Alan Turing, who suggested that if someone talking to another person and to a computer couldn’t tell which was which, then that computer could be said to think. And thinking, in turn, is a sign of being human.

Contest judges don’t actually talk with the computers, they exchange chat messages with a computer and a volunteer, then try to identify which of the two is the human. A computer that convinces enough judges that it’s human wins the solid gold Loebner medal and the $100,000 prize that accompanies it, or at least its programmer does.

Here are some excerpts from the 2011 contest rules to show how the test works:

Judges will begin each round by making initial comments with the entities. Upon receiving an utterance from a judge, the entities will respond. Judges will continue interacting with the entities for 25 minutes. At the conclusion of the 25 minutes, each judge will declare one of the two entities to be the human.

Judges will begin each round by making initial comments with the entities. Upon receiving an utterance from a judge, the entities will respond. Judges will continue interacting with the entities for 25 minutes. At the conclusion of the 25 minutes, each judge will declare one of the two entities to be the human.

At the completion of the contest, Judges will rank all participants on “humanness.”

If any entry fools two or more judges comparing two or more humans into thinking that the entry is the human, the $25,000 and Silver Medal will be awarded to the submitter(s) of the entry and the contest will move to the Audio Visual Input $100,000 Gold Medal level.

Notice that both the computer entrants and the human volunteers are referred to in these rules as “entities,” a word calculated to eliminate any pro-human bias among the judges, not that such a bias exists in the world of Artificial Intelligence. In addition, the computers are called “participants,” which actually gives a bump to the machines, since it’s a term that’s usually reserved for human contestants. Since the rules sound like they were written by a computer, not by a human, passing the Turing test should be a snap for any halfway decent programmer.

But even though these Turing competitions have been staged since 1991, when computer scientist Hugh Loebner first offered the Loebner medal for the most human computer, so far no computer has claimed the go

But even though these Turing competitions have been staged since 1991, when computer scientist Hugh Loebner first offered the Loebner medal for the most human computer, so far no computer has claimed the go

By: Lauren,

on 3/23/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

US,

Dictionaries,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

1837,

all correct,

boston morning post,

okay,

this day in history,

ok,

history of ok,

o.k.,

oll korrect,

van buren,

william henry harrison,

Add a tag

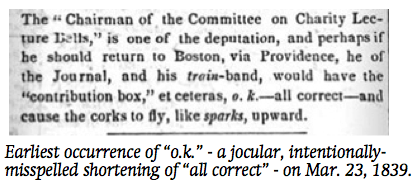

By Dennis Baron

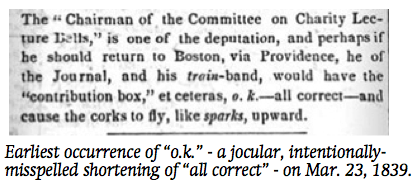

By rights, OK should not have become the world’s most popular word. It was first used as a joke in the Boston Morning Post on March 23, 1839, a shortening of the phrase “oll korrect,” itself an incorrect spelling of “all correct.” The joke should have run its course, and OK should have been forgotten, just like we forgot the other initialisms appearing in newspapers at the time, such as O.F.M, ‘Our First Men,’ A.R., ‘all right,’ O.W., ‘oll wright,’ K.G., ‘know good,’ and K.Y., ‘know yuse.’ Instead, here we are celebrating OK’s 172nd birthday, wondering why the word became a lexical universal instead of a one day wonder.

By rights, OK should not have become the world’s most popular word. It was first used as a joke in the Boston Morning Post on March 23, 1839, a shortening of the phrase “oll korrect,” itself an incorrect spelling of “all correct.” The joke should have run its course, and OK should have been forgotten, just like we forgot the other initialisms appearing in newspapers at the time, such as O.F.M, ‘Our First Men,’ A.R., ‘all right,’ O.W., ‘oll wright,’ K.G., ‘know good,’ and K.Y., ‘know yuse.’ Instead, here we are celebrating OK’s 172nd birthday, wondering why the word became a lexical universal instead of a one day wonder.

Most of the “abracadabraisms” popular among journalists in 1839 are long gone, but OK stuck around. It didn’t go viral right away, perhaps because the first virus wouldn’t be discovered for another 60 years, but unlike A.R. and K.Y., OK managed to spread beyond comic articles in newspapers, to become a word on almost everybody’s lips. For that to happen, we had to forget what OK originally meant, a jokey informal word indicating approval, and then we had to repurpose it to mean almost anything, or in some cases, almost nothing at all.

Here’s that first OK, discovered almost 50 years ago by the linguist Alan Walker Read:

he of the Journal . . . would have the “contribution box,” et ceteras, o.k.—all correct—and cause the corks to fly, like sparks, upward. [“He” is the editor of the rival Providence paper, and the subject of the article, the shenanigans of rowdy journalists and their friends, is so trivial that explaining it in no way explains OK’s success.]

The fact that the writer, the Post’s editor Charles Gordon Greene, defines OK as “all correct” confirms its novelty—readers wouldn’t be expected to know what it meant. But because readers were already used to jokey initialisms, Greene expected them to connect “oll korrect” and “all correct” on their own. He didn’t have to ask, “OK, Get it?” or add a final “Haha” to the message.

But why did OK have more staying power than yesterday’s newspaper? One thing that kept OK going after its March 23, 1839 sell-by date was its adoption by the 1940 re-election campaign of Pres. Martin Van Buren. Van Buren, born in Kinderhook, New York, was known as Old Kinderhook, and his political machine operated out of New York’s O.K. (Old Kinderhook) Democratic Club. The coincidence between “Old Kinderhook” and “oll korrect” proved a sloganeer’s dream, as this notice for a political rally illustrates:

The Democratic O.K. Club are hereby ordered to meet at the House of Jacob Colvin. [1840, Oxford English Dictionary, known more commonly by the initialism OED]

That campaign may have helped OK more than it helped Van Buren, who was definitely not OK: he was blamed for the financial crisis of 1837 and roundly trounced in the election by William Henry Harrison. Harrison himself wasn’t so OK: he died from pneumonia a month after giving a 2-hour inaugural address in the rain, but OK got national exposure, and it was soon tapped as one of many shorthand expressions (like gmlet for ‘give my love to’) serving the new telegraph, the “Victorian internet” that began spre

By: Lauren,

on 3/4/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

grammar,

George W. Bush,

national grammar day,

english,

punctuation,

Schoolhouse Rock,

spogg,

grammarians,

commas,

Web of Language,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar,

Add a tag

(Click here to take the National Grammar Day quiz at Web of Language!)

By Dennis Baron

March 4 is National Grammar Day. According to its sponsor, the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar (SPOGG, they call themselves, though between you and me, it’s not the sort of acronym to roll trippingly off the tongue), National Grammar Day is “an imperative . . . . to speak well, write well, and help others do the same!”

March 4 is National Grammar Day. According to its sponsor, the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar (SPOGG, they call themselves, though between you and me, it’s not the sort of acronym to roll trippingly off the tongue), National Grammar Day is “an imperative . . . . to speak well, write well, and help others do the same!”

The National Grammar Day website is full of imperatives about correct punctuation, pronoun use, and dangling participles. In the spirit of good sportsmanship, it points out an error in the Olympic theme song, “I believe.” The song contains the phrase the power of you and I (that’s a common idiom in English, even in Canada, plus it rhymes with fly in the previous line of the song), but SPOGG would prefer you and me. There’s even a link to vote for your favorite Schoolhouse Rock grammar episode (hint: unless you prefer grammar rules that have nothing to do with the language people actually speak, don’t pick “A Noun is the Name of a Person, Place, or Thing“).

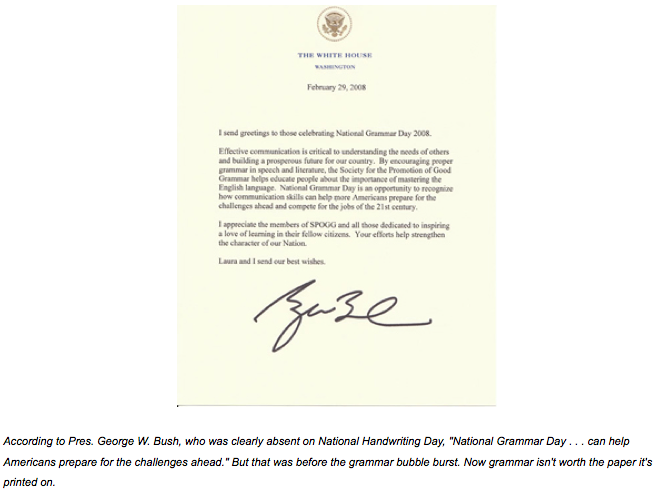

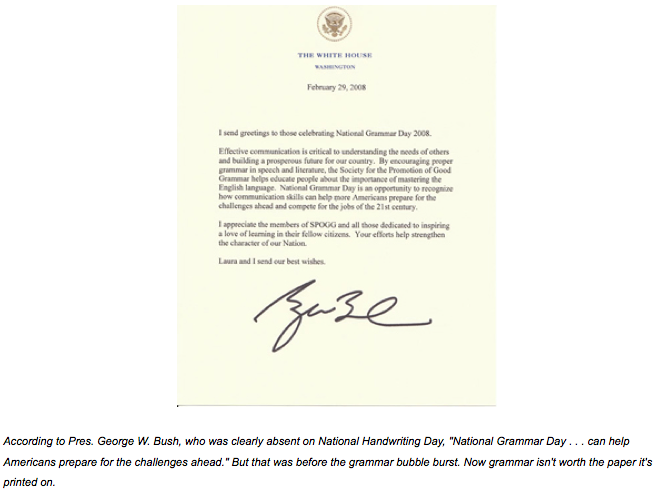

The National Grammar Day home page has even got its own grammar song available for download, though it’s of less than Olympic quality, and the site also boasts a letter of support from former Pres. George W. Bush, apparently SPOGG’s poster child for good grammar, who writes that “National Grammar Day . . . can help Americans prepare for the challenges ahead.” To be sure, Bush wrote that before the grammar bubble burst. The growing number of grammarians filing first-time unemployment claims suggests that the former president was wrong about this, as he was about most things.

You might be tempted to ask why National Grammar Day is different from all other days (it’s O.K. to ask that, so long as you don’t want to know why it’s very unique). National Grammar Day is a day to set aside everyday English and follow special rules that have nothing to do with how people actually talk or write. On all other days, we split our infinitives and start sentences with and and but. But on National Grammar day, we avoid but altogether and utter no verbs at all. On all other days we use like for as. On National Grammar Day, we like nobody else’s grammar all day long. On all other days, we use hopefully as a sentence adverbial. On National Grammar Day, we are no longer sanguine about anyone’s ability to speak or write correctly, and we only expect the worst. Or we expect only the worst.

Over the course of the year there are all sorts of language-themed holidays: National Handwriting Day, National Writing Day, Dictionary Day, English Language Day, Mother Language Day, even, comma, open quotes “Punctuation Day period close quotes.” In England they celebrate Punctuation Day with “close quotes period”. And now, since 2008, we’ve had National Grammar Day as well

By: Lauren,

on 2/28/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Law,

US,

writing,

Dictionaries,

oxford english dictionary,

definition,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

dictionary act,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

There’s a federal law that defines writing. Because the meaning of the words in our laws isn’t always clear, the very first of our federal laws, the Dictionary Act–the name for Title 1, Chapter 1, Section 1, of the U.S. Code–defines what some of the words in the rest of the Code mean, both to guide legal interpretation and to eliminate the need to explain those words each time they appear. Writing is one of the words it defines, but the definition needs an upgrade.

The Dictionary Act consists of a single sentence, an introduction and ten short clauses defining a minute subset of our legal vocabulary, words like person, officer, signature, oath, and last but not least, writing. This is necessary because sometimes a word’s legal meaning differs from its ordinary meaning. But changes in writing technology have rendered the Act’s definition of writing seriously out of date.

The Dictionary Act tells us that in the law, singular includes plural and plural, singular, unless context says otherwise; the present tense includes the future; and the masculine includes the feminine (but not the other way around–so much for equal protection).

The Act specifies that signature includes “a mark when the person making the same intended it as such,” and that oath includes affirmation. Apparently there’s a lot of insanity in the law, because the Dictionary Act finds it necessary to specify that “the words ‘insane’ and ‘insane person’ and ‘lunatic’ shall include every idiot, lunatic, insane person, and person non compos mentis.”

The Dictionary Act also tells us that “persons are corporations . . . as well as individuals,” which is why AT&T is currently trying to convince the Supreme Court that it is a person entitled to “personal privacy.” (The Act doesn’t specify whether “insane person” includes “insane corporation.”)

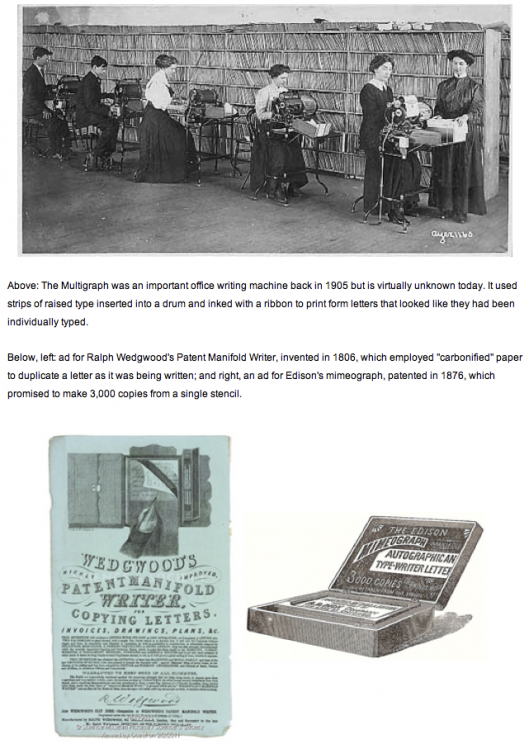

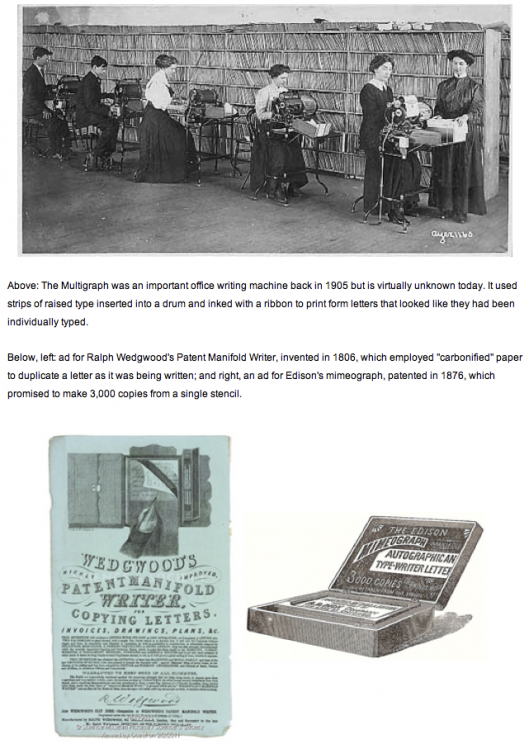

And then there’s the definition of writing. The final provision of the Act defines writing to include “printing and typewriting and reproductions of visual symbols by photographing, multigraphing, mimeographing, manifolding, or otherwise.” There’s no mention of Braille, for example, or of photocopying, or of computers and mobile phones, which seem now to be the primary means of transmitting text, though presumably they and Facebook and Twitter and all the writing technologies that have yet to appear are covered by the law’s blanket phrase “or otherwise.”

Federal law can’t be expected to keep up with every writing technology that comes along, but the newest of the six kinds of writing that the Dictionary Act does refer to–the multigraph–was invented around 1900 and has long since disappeared. No one has ever heard of multigraphing, or of manifolding, an even older and deader technology, and for most of us the mimeograph is at best a dim memory.

Congress considers writing important enough to the nation’s well-being to include it in the Dictionary Act, but not important enough to bring up to date, and now, with the 2012 election looming, no member of Congress is likely to support a revision to the current definition that is semantically accurate yet co

By: Lauren,

on 2/17/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Cuba,

internet,

Technology,

Politics,

Current Events,

facebook,

Media,

Middle East,

twitter,

Egypt,

Revolution,

Dennis Baron,

cairo,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

mubarak,

Ben Ali,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

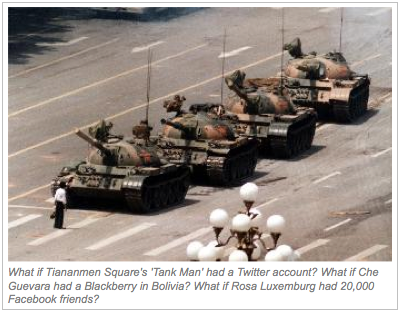

Western observers have been celebrating the role of Twitter, Facebook, smartphones, and the internet in general in facilitating the overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak in Egypt last week. An Egyptian Google employee, imprisoned for rallying the opposition on Facebook, even became for a time a hero of the insurgency. The Twitter Revolution was similarly credited with fostering the earlier ousting of Tunisia’s Ben Ali, and supporting Iran’s green protests last year, and it’s been instrumental in other outbreaks of resistance in a variety of totalitarian states across the globe. If only Twitter had been around for Tiananmen Square, enthusiasts retweeted one another. Not bad for a site that started as a way to tell your friends what you had for breakfast.

But skeptics point out that the crowds in Cairo’s Tahrir Square continued to grow during the five days that the Mubarak government shut down the internet; that only nineteen percent of Tunisians have online access; that while the Iran protests may have been tweeted round the world, there were few Twitter users actually in-country; and that although Americans can’t seem to survive without the constant stimulus of digital multitasking, much of the rest of the world barely notices when the cable is down, being preoccupied instead with raising literacy rates, fighting famine and disease, and finding clean water, not to mention a source of electricity that works for more than an hour every day or two.

But skeptics point out that the crowds in Cairo’s Tahrir Square continued to grow during the five days that the Mubarak government shut down the internet; that only nineteen percent of Tunisians have online access; that while the Iran protests may have been tweeted round the world, there were few Twitter users actually in-country; and that although Americans can’t seem to survive without the constant stimulus of digital multitasking, much of the rest of the world barely notices when the cable is down, being preoccupied instead with raising literacy rates, fighting famine and disease, and finding clean water, not to mention a source of electricity that works for more than an hour every day or two.

It’s true that the internet connects people, and it’s become an unbeatable source of information—the Egyptian revolution was up on Wikipedia faster than you could say Wolf Blitzer. The telephone also connected and informed faster than anything before it, and before the telephone the printing press was the agent of rapid-fire change. All these technologies can foment revolution, but they can also be used to suppress dissent.

You don’t have to master the laws of physics to observe that for every revolutionary manifesto there’s an equal and opposite volley of government propaganda. For every eye-opening book there’s an index librorum prohibitorum—an official do-not-read list—or worse yet, a bonfire. For every phone tree organizing a protest rally there’s a warrantless wiretap waiting to throw the rally-goers in jail. And for every revolutionary internet site there’s a firewall, or in the case of Egypt, a switch that shuts it all down. Cuba is a country well-known for blocking digital access, but responding to events in Egypt and the small but scary collection of island bloggers, El Lider’s government is sponsoring a dot gov rebuttal, a cadre of official counterbloggers spreading the party line to the still small number of Cubans able to get online—about ten percent can access the official government-controlled ’net—or get a cell phone signal in their ’55 Chevys.

You don’t have to master the laws of physics to observe that for every revolutionary manifesto there’s an equal and opposite volley of government propaganda. For every eye-opening book there’s an index librorum prohibitorum—an official do-not-read list—or worse yet, a bonfire. For every phone tree organizing a protest rally there’s a warrantless wiretap waiting to throw the rally-goers in jail. And for every revolutionary internet site there’s a firewall, or in the case of Egypt, a switch that shuts it all down. Cuba is a country well-known for blocking digital access, but responding to events in Egypt and the small but scary collection of island bloggers, El Lider’s government is sponsoring a dot gov rebuttal, a cadre of official counterbloggers spreading the party line to the still small number of Cubans able to get online—about ten percent can access the official government-controlled ’net—or get a cell phone signal in their ’55 Chevys.

All new means of communication bring with them an irrepressible excitement as they expand literacy and open up new knowledge, but in certain quarters they also spark fear and distrust. At the very least, civil and religious authorities start insisting on an imprimatur—literally, a permission to print—to license communication and censor content, channeling it al

By: Lauren,

on 1/28/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Law,

george orwell,

grammar,

Current Events,

macbeth,

linguistics,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Gabrielle Giffords,

Jared Loughner,

David Wynn Miller,

tuscon shooting,

progressive—birnam,

will—birnam,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

Despite the claims of mass murderers and freepers, the government does not control your grammar. The government has no desire to control your grammar, and even if it did, it has no mechanism for exerting control: the schools, which are an arm of government, have proved singularly ineffective in shaping students’ grammar. Plus every time he opened his mouth, Pres. George W. Bush proved that the government can’t even control its own grammar.

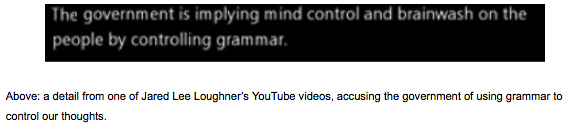

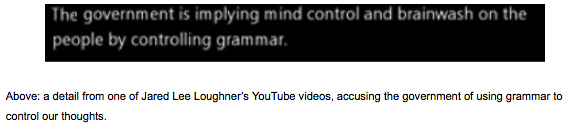

Nonetheless, grammar conspiracy theories abound. In a YouTube video, Jared Lee Loughner, arrested for the Tucson assassinations that so shocked the nation, warns, “The government is implying mind control and brainwash on the people by controlling your grammar.” As further evidence that Loughner’s own grasp both of grammar and of reality is tenuous, he is reported to have asked Rep. Gabrielle Giffords the truly bizarre question, “What is government if words have no meaning?” three years before he put a bullet through the left side of her brain, the part that controls language.

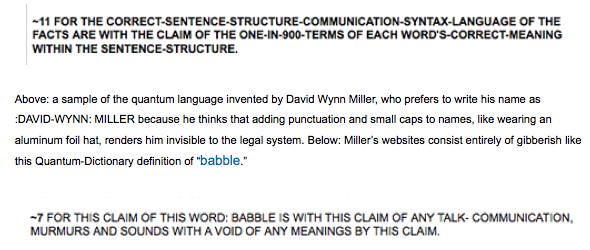

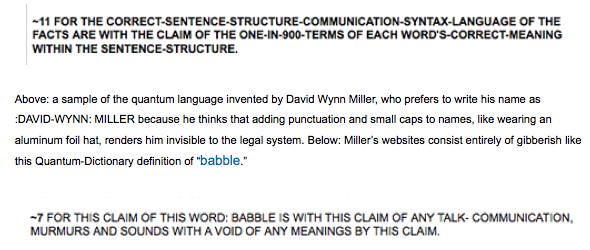

But wresting control of grammar away from the government the same way other revolutionaries might take over the newspapers and the radio stations is the underlying theme of another denier of government authority, the right-wing loony-toon David Wynn Miller, a former pipe-fitter who made up his own language in order to challenge the government’s legitimacy and avoid paying taxes. News accounts detail attempts by Miller’s followers, after attending his expensive how-to seminars, to bring the courts to a standstill by filing stacks of incomprehensible legal motions written in what Miller calls “Quantum Language,” or sometimes, “communication-syntax-language,” but is literally psychobabble.

The idea that government controls language, which appeals to conspiracy theorists, is just a subset of the more-commonly-held view that language controls thought. George Orwell used Newspeak to illustrate this kind of linguistic mind control in his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), and in his essay “Politics and the English Language (1946), where he decried the connection between “politics and the debasement of language.” In the essay, Orwell presents a “catalogue of swindles and perversions” of words like “class, totalitarian, science, progressive, reactionary, bourgeois, equality“–together with syntactic forms like the passive voice. Orwell claimed that all of these were used in political writing “in most cases more or less dishonestly,” and, using the passive voice, he added that “political language . . . is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”  0 Comments on The Government Does Not Control Your Grammar as of 1/28/2011 6:14:00 AM

0 Comments on The Government Does Not Control Your Grammar as of 1/28/2011 6:14:00 AM

By Dennis Baron

“It’s not surprising then that they get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them or anti-immigrant sentiment or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations.” –Barack Obama

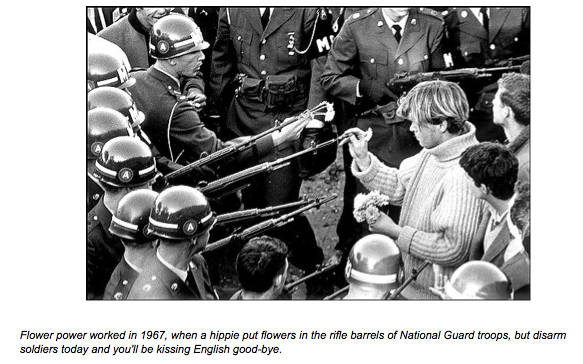

The bumper sticker on the back of a construction worker’s pickup truck caught my eye: “If you can read this, thank a teacher.”

This homage to education wasn’t what I expected from someone whose bitterness typically manifests itself in vehicle art celebrating guns and religion, but there was more: “If you can read this in English, thank a soldier.”

It was a “support our troops” bumper sticker that takes language and literacy out of the classroom and puts them squarely in the hands of the military.

It’s one thing to say that we owe our national security and the survival of the free world to military might. It’s something else again to be told that we need soldiers to protect the English language.

But according to this bumper sticker, any chink in our armor, any relaxation of our constant vigilance, any momentary lowering of the gun barrel, and we’ll all be speaking Russian, Iraqi, or even Mexican.

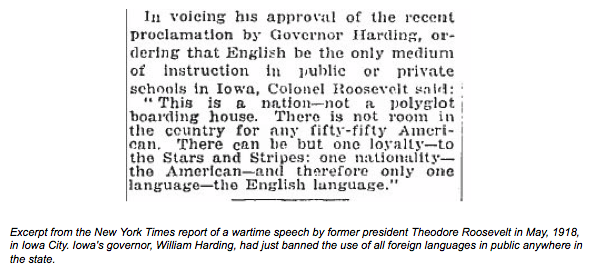

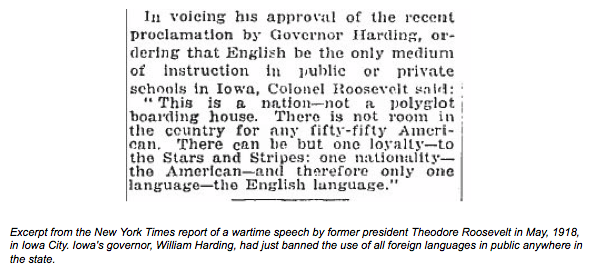

Supporters of official English argue that it’s the language of democracy — the language of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, not to mention the “Star-Spangled Banner,” “American Idol” and “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” (it doesn’t matter that Millionaire was a British show first, since Americans were British once themselves). English, goes the claim, is the “social glue” cementing the many cultures that underlie American culture. As Teddy Roosevelt said back in 1918, “This is a nation, not a polyglot boarding house.”

Supporters of official English argue that it’s the language of democracy — the language of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, not to mention the “Star-Spangled Banner,” “American Idol” and “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” (it doesn’t matter that Millionaire was a British show first, since Americans were British once themselves). English, goes the claim, is the “social glue” cementing the many cultures that underlie American culture. As Teddy Roosevelt said back in 1918, “This is a nation, not a polyglot boarding house.”

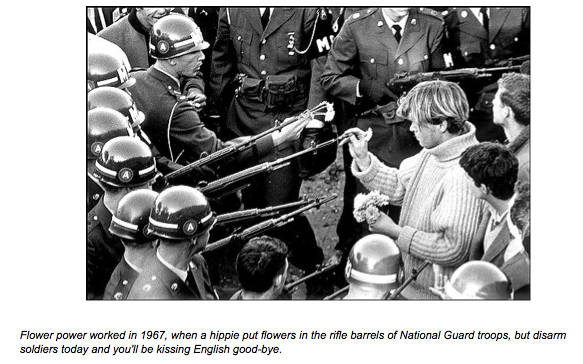

But apparently even the official language laws that states, cities, schools and businesses have put in place aren’t doing the job, so what we really need is to put a gun to people’s heads to make them use English.

Only that won’t work. The large number of translators killed in Iraq, or drummed out of the army for being gay, are two of the many indicators that our armies aren’t keeping the world safe for English.

The linguist Max Weinreich is credited with quipping that a language is a dialect with an army and a navy. But guns can’t literally keep a language safe at home any more than they can effectively seal a border to keep other languages out.

In a bold act of regime change and a glaring breach of homeland security, French streamed across the English borders in the 11th century along with the Norman armies, but French soldiers were unable to convert most of the Brits they encountered to the parlez-vous, at least not in the long term.

And while the Royal Navy helped spread English around the globe as part and parcel of the British Empire, what really undergirds English today as an international language isn’t military might, but the appeal of global capitalism, science, computer technology, t-shirts, and good old rock ‘n

By Dennis Baron

People judge you by the words you use. This warning, once the slogan of a vocabulary building course, is now the mantra of the new science of culturomics.

People judge you by the words you use. This warning, once the slogan of a vocabulary building course, is now the mantra of the new science of culturomics.

In “Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books” (Michel, et al., Science, Dec. 17, 2010), a Harvard-led research team introduces “culturomics” as “the application of high throughput data collection and analysis to the study of human culture.” In plain English, they crunched a database of 500 billion words contained in 5 million books published between 1500 and 2008 in English and several other languages and digitized by Google. The resulting analysis provides insight into the state of these languages, how they change, and how they reflect culture at any given point in time.

In still plainer English, they turned Google Books into a massively-multiplayer online game where players track word frequency and guess what writers from 1500 to 2008 were thinking, and why. The words you use tell the culturonomists exactly who you are–and they can even graph the results!

According to the psychologists and mathematicians on the culturomics team, reducing books and their words to numbers and graphs will finally give the fuzzy humanistic interpretation of history, literature, and the arts the rigorous scientific footing it has lacked for so long.

For example, the graph below tracks the frequency of the name Marc Chagall (1887-1985) in English and German books from 1900 to 2000, revealing a sharp dip in German mentions of the modernist Jewish artist from 1933 to 1945. You don’t need a graph to correlate Hitler’s ban on Chagall and his work with the artist’s disappearance from German print (other Jewish artists weren’t just censored by the Nazis, they were murdered), but it is interesting to note that both before and after the Hitler era, Chagall garners significantly more mentions in German books than he does in English ones.

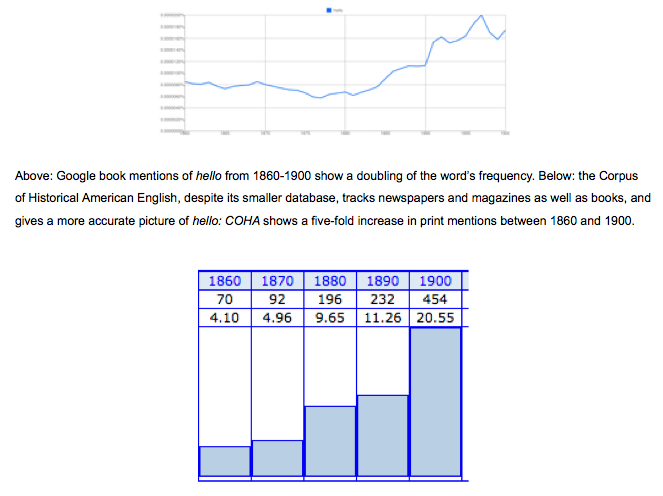

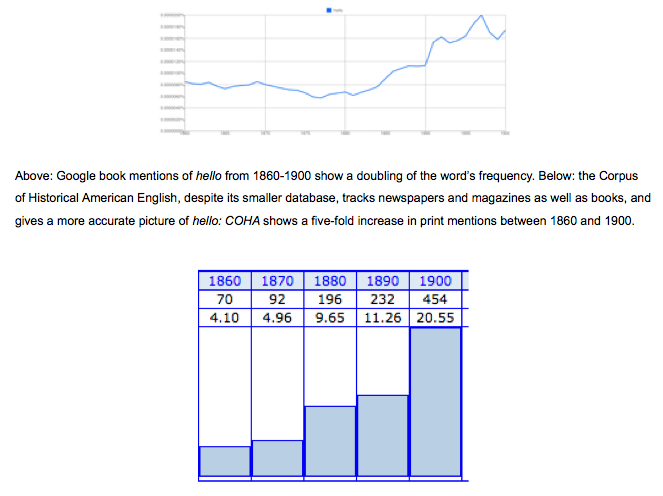

One problem with the culturome data set is that books don’t always reflect the spoken language accurately. When the telephone was invented in 1876, Americans adapted hello as a greeting to use when answering calls. Before that time, hello was an extremely rare word that served as a way of hailing a boat or as an expression of surprise. But as the telephone spread across American cities, hello quickly became the customary greeting both for telephone, and then for face-to-face, conversation.

Expanding the data set of written English to include not just books but also newspapers, periodicals, letters, and informal writing, as we find in the smaller, 400-million word Corpus of Historical American English, gives a better idea of the frequency of words like hello. But crunching numbers doesn’t tell the whole story: we can infer from contemporary published accounts, many of them strong objections to the new term, that hello is much more common in speech than its occurrence in writing indicates.

It’s one thing to read a book and speculate about its meaning—that’s what readers are supposed to do. But culturomics crunches millions of books—more than the most ardent book club groupie could get through in a lifetime. Since mos

By Dennis Baron

Everybody knows that a noun is the name of a person, place, or thing. It’s one of those undeniable facts of daily life, a fact we seldom question until we meet up with a case that doesn’t quite fit the way we’re used to viewing things.

That’s exactly what happened to a student in Ohio when his English teacher decided to play the noun game. To the teacher, the noun game seemed a fun way to take the drudgery out of grammar. To the student it forced a metaphysical crisis. To me it shows what happens when cultures clash and children get lost in the tyranny of school. That’s a lot to get from a grammar game.

Anyway, here’s how you play. Every student gets a set of cards with nouns written on them. At the front of the classroom are three buckets, labeled “person,” “place,” and “thing.” The students take turns sorting their cards into the appropriate buckets. “Book” goes in the thing bucket. “city” goes in the place bucket. “Gandhi” goes in the person bucket.

Ganesh had a card with “horse” on it. Ganesh isn’t his real name, by the way. It’s actually my cousin’s name, so I’m going to use it here.

You might guess from his name that Ganesh is South Asian. In India, where he had been in school before coming to Ohio, Ganesh was taught that a noun named a person, place, thing, or animal. If he played the noun game in India he’d have four buckets and there would be no problem deciding what to do with “horse.” But in Ohio Ganesh had only three buckets, and it wasn’t clear to him which one he should put “horse” in.

In India, Ganesh’s religion taught him that all forms of life are continuous, interrelated parts of the universal plan. So when he surveyed the three buckets it never occurred to him that a horse, a living creature, could be a thing. He knew that horses weren’t people, but they had more in common with people than with places or things. Forced to choose, Ganesh put the horse card in the person bucket.

Blapp! Wrong! You lose. The teacher shook her head, and Ganesh sat down, mortified, with a C for his efforts. This was a game where you got a grade, and a C for a child from a South Asian family of overachievers is a disgrace. So his parents went to talk to the teacher.

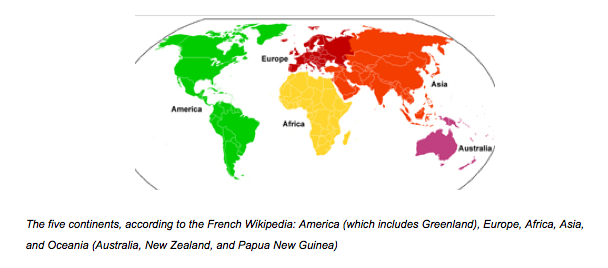

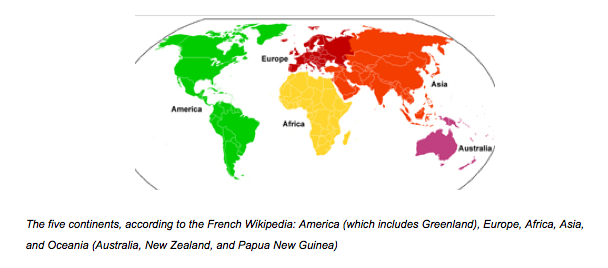

It so happens that I’ve been in a similar situation. We spent a year in France some time back, and my oldest daughter did sixth grade in a French school. The teacher asked her, “How many continents are there?” and she replied, as she had been taught in the good old U.S. of A., “seven.” Blaap! Wrong! It turns out that in France there are only five.

So old dad goes to talk to the teacher about this. I may not be able to remember the seven dwarfs, but I rattled off Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, Antarctica, North America, and South America. The teacher calmly walked me over to the map of the world. Couldn’t I see that Antarctica was an uninhabited island? And couldn’t I see that North and South America were connected? Any fool could see as much.

At that point I decided not to press the observation that Europe and Asia were also connected. Some things are not worth fighting for when you’re fighting your child’s teacher.

By Dennis Baron

Last Spring the New York Times reported that more and more grammar vigilantes are showing up on Twitter to police the typos and grammar mistakes that they find on users’ tweets. According to the Times, the tweet police “see themselves as the guardians of an emerging behavior code: Twetiquette,” and some of them go so far as to write algorithms that seek out tweets gone wrong (John Metcalfe, “The Self-Appointed Twitter Scolds,” April 28, 2010).

Last Spring the New York Times reported that more and more grammar vigilantes are showing up on Twitter to police the typos and grammar mistakes that they find on users’ tweets. According to the Times, the tweet police “see themselves as the guardians of an emerging behavior code: Twetiquette,” and some of them go so far as to write algorithms that seek out tweets gone wrong (John Metcalfe, “The Self-Appointed Twitter Scolds,” April 28, 2010).

Twitter users post “tweets,” short messages no longer than 140 characters (spaces included). That length restriction can lead to beautifully-crafted, allusive, high-compression tweets where every word counts, a sort of digital haiku. But most tweets are not art. Instead, most users use Twitter to tell friends what they’re up to, send notes, and make offhand comments, so they squeeze as much text as possible into that limited space by resorting to abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and numbers for letters, the kind of shorthand also found, and often criticized, in texting on a mobile phone.

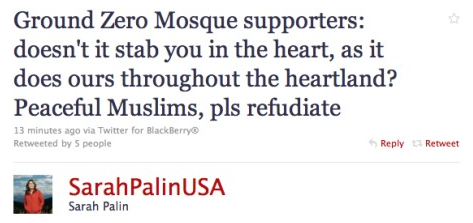

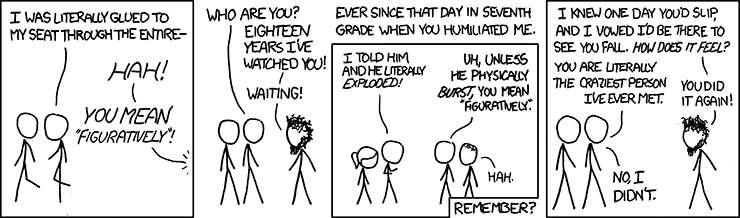

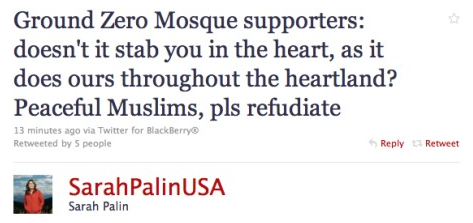

But what the tweet police are looking for are more traditional usage gaffes, like problems with subject-verb agreement, misspellings, or incorrect use of apostrophes. And they don’t like mistakes in word choice, as when Sarah Palin tweeted refudiate, not repudiate, in her objection to the Islamic Cultural Center being built near Ground Zero in lower Manhattan.

Palin is one of the celebrities on Twitter whose posts get a lot of scrutiny from the grammar watchers. But while refudiate was perceived to be an error, it’s not exactly a new word. According to Ammon Shea, it first appeared in 1891, and Ben Zimmer finds it surfacing again in 1925.

The immediate clamor that followed Palin’s use of refudiate in her July 18, 2010, tweet led Palin or someone on her staff to replace the original tweet with the edited version below. However, switching refudiate to refute didn’t placate the language purists, who insisted that she should have said repudiate.

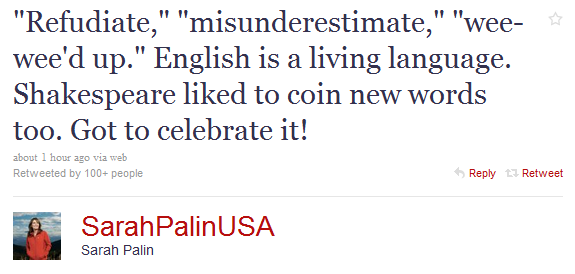

In a tweet later that same day (below), Palin decided to recast her mistake as an experiment in creativity, arguing that word coinage is common in English and suggesting that her use of refudiate was somehow Shakespearean.

As if to prove her point, the editors of the

0 Comments on ” :) when you say that, pardner” – the tweet police are watching as of 1/1/1900

You don’t have to master the laws of physics to observe that for every revolutionary manifesto there’s an equal and opposite volley of government propaganda. For every eye-opening book there’s an index librorum prohibitorum—an official do-not-read list—or worse yet, a bonfire. For every phone tree organizing a protest rally there’s a warrantless wiretap waiting to throw the rally-goers in jail. And for every revolutionary internet site there’s a firewall, or in the case of Egypt,

You don’t have to master the laws of physics to observe that for every revolutionary manifesto there’s an equal and opposite volley of government propaganda. For every eye-opening book there’s an index librorum prohibitorum—an official do-not-read list—or worse yet, a bonfire. For every phone tree organizing a protest rally there’s a warrantless wiretap waiting to throw the rally-goers in jail. And for every revolutionary internet site there’s a firewall, or in the case of Egypt,

Last Spring the New York Times reported that more and more grammar vigilantes are showing up on Twitter to police the typos and grammar mistakes that they find on users’ tweets. According to the Times, the tweet police “see themselves as the guardians of an emerging behavior code: Twetiquette,” and some of them go so far as to write algorithms that seek out tweets gone wrong (John Metcalfe,

Last Spring the New York Times reported that more and more grammar vigilantes are showing up on Twitter to police the typos and grammar mistakes that they find on users’ tweets. According to the Times, the tweet police “see themselves as the guardians of an emerging behavior code: Twetiquette,” and some of them go so far as to write algorithms that seek out tweets gone wrong (John Metcalfe,