new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: French Revolution, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 16 of 16

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: French Revolution in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: RachelM,

on 10/16/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Religion,

Education,

Oxford,

paris,

Bologna,

Europe,

theology,

French Revolution,

Universities,

*Featured,

silicon valley,

Arts & Humanities,

19th century philosophers,

history of the university,

the enlightenment,

the New World,

Theology and the University in Nineteenth-Century Germany,

Zachary Purvis,

Add a tag

By nearly all accounts, higher education has in recent years been lurching towards a period of creative destruction. Presumed job prospects and state budgetary battles pit the STEM disciplines against the humanities in much of our popular and political discourse. On many fronts, the future of the university, at least in its recognizable form as a veritable institution of knowledge, has been cast into doubt.

The post The University: past, present, … and future? appeared first on OUPblog.

-->

By: Samantha Zimbler,

on 11/16/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

marie antoinette,

Europe,

French Revolution,

French politics,

French History,

*Featured,

Online products,

King Louis XVI,

OHO,

oxford handbooks online,

Arts & Humanities,

franco-Austrian relations,

Joseph II,

Oxford Handbook of the Ancien Regime,

Oxford Handbooks in History,

The Old Regime,

Thomas E. Kaiser,

Thomas Kaiser,

History,

Add a tag

Although most historians of the French Revolution assign the French queen Marie-Antoinette a minor role in bringing about that great event, a good case can be made for her importance if we look more deeply into her politics than most scholars have.

The post Marie-Antoinette and the French Revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Amelia Carruthers,

on 7/26/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

France,

facts,

marie antoinette,

Europe,

Revolution,

French Revolution,

guillotine,

French History,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Bastille,

Robespierre,

Arts & Humanities,

listicle,

Brissot,

Choosing Terror,

facts about french revolution,

Girondins,

historical facts,

Jacobins,

Let them eat cake,

Marisa Linton,

Thermidor,

Books,

History,

myths,

Add a tag

The French Revolution was one of the most momentous events in world history yet, over 220 years since it took place, many myths abound. Some of the most important and troubling of these myths relate to how a revolution that began with idealistic and humanitarian goals resorted to ‘the Terror’.

The post Ten myths about the French Revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Clare Hanson,

on 7/14/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

democracy,

Politics,

government,

French Revolution,

philosopher,

Bastille Day,

French politics,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

Kant,

PolSci,

National Day of France,

Reidar Maliks,

Add a tag

The French celebrate their National Day each year on July 14 by remembering the storming of the Bastille, the hated symbol of the old regime. According to the standard narrative, the united people took the law in its own hands and gave birth to modern France in a heroic revolution. But in the view of Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), the famous German philosopher, there was no real revolution, understood as an unlawful and violent toppling of the old regime.

The post Was the French revolution really a revolution? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KatherineS,

on 6/12/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

democracy,

American Revolution,

VSI,

British,

pope,

Very Short Introductions,

parliament,

French Revolution,

english civil war,

A Very Short Introduction,

King John,

*Featured,

richard II,

Medieval History,

magna carta,

VSI online,

Series & Columns,

1215,

800th anniversary,

barons,

Habeas Corpus,

Runnymede,

trial by jury,

Add a tag

On 15th June 2015, Magna Carta celebrates its 800th anniversary. More has been written about this document than about virtually any other piece of parchment in world history. A great deal has been wrongly attributed to it: democracy, Habeas Corpus, Parliament, and trial by jury are all supposed somehow to trace their origins to Runnymede and 1215. In reality, if any of these ideas are even touched upon within Magna Carta, they are found there only in embryonic form.

The post The greatest charter? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Raquel Fernandes,

on 3/10/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Music,

French Revolution,

Napoleon,

Berlioz,

*Featured,

1830,

Arts & Humanities,

Beethovan,

Berlioz on Music,

Hector Berlioz,

Katherine Kolb,

Samuel N. Rosenberg,

Selected Criticism 1824-1837,

Add a tag

That Beethoven welcomed the French Revolution and admired Napoleon, its most flamboyant product, is common knowledge. So is the story of his outrage at the news that his hero, in flagrant disregard of liberté, égalité, fraternité, had had himself crowned emperor: striking the dedication to Napoleon of his "Eroica" symphony, he addressed it instead "to the memory of a great man."

The post Beethoven and the Revolution of 1830 appeared first on OUPblog.

By:

Bianca Schulze,

on 12/10/2014

Blog:

The Children's Book Review

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Young Adult Fiction,

Historical Fiction,

Art,

Romance,

Chapter Books,

France,

Paris,

Orphans,

Suspense,

Books for Girls,

French Revolution,

Teens: Young Adults,

Merit Press Books,

Kathleen Benner Duble,

Add a tag

Madame Tussaud's Apprentice is a fascinating historical drama. The rich background of revolutionary France provides readers with a fascinating look at that terrifying time.

By: ChloeF,

on 8/4/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

peace,

war,

Europe,

French Revolution,

European history,

Napoleon,

French History,

*Featured,

munro,

tuileries,

UKpophistory,

King Louis XVI,

Munro Price,

Napoleon the end of glory,

schwarzenberg,

schwarzenberg’s,

napoleon’s,

delaroche,

Add a tag

By Munro Price

On 9 April 1813, only four months after his disastrous retreat from Moscow, Napoleon received the Austrian ambassador, Prince Schwarzenberg, at the Tuileries palace in Paris. It was a critical juncture. In the snows of Russia, Napoleon had just lost the greatest army he had ever assembled – of his invasion force of 600,000, at most 120,000 had returned. Now Austria, France’s main ally, was offering to broker a deal – a compromise peace – between Napoleon and his triumphant enemies Russia and England. Schwarzenberg’s visit to the Tuileries was to start the negotiations.

Schwarzenberg’s description of the meeting is one of the most revealing insights into Napoleon’s character from any source. In place of the imperious conqueror of only ten months before, Schwarzenberg now saw a man who feared ‘being stripped of the prestige he [had] previously enjoyed; his expression seemed to ask me if I still thought he was the same man.’

To Schwarzenberg’s dismay, when it came to peace Napoleon still showed his old obstinacy and unwillingness to make concessions. The reason for this, however, was unexpected. It concerned not diplomacy or the military situation, but Napoleon’s domestic position in France. He told Schwarzenberg:

“If I made a dishonourable peace I would be lost; an old-established government, where the links between ruler and people have been forged over centuries can, if circumstances demand, accept a harsh peace. I am a new man, I need to be more careful of public opinion … If I signed a peace of this sort, it is true that at first one would hear only cries of joy, but within a short time the government would be bitterly attacked, I would lose … the confidence of my people, because the Frenchman has a vivid imagination, he is tough, and loves glory and exaltation.”

Napoleon’s reluctance to make peace at this key moment has been generally ascribed to his gambling instinct, a refusal to accept that Destiny might desert him, and a desperate belief he could still defeat his enemies in battle even now. The idea that fear might also have played a part seems so alien to Napoleon’s character that it has rarely been considered.

Napoleon was convinced, as his words to Schwarzenberg made clear, that the best way of anchoring any new régime was through military glory. Nowhere was this truer, he felt than in France, which had just undergone a revolution of unprecedented scale and violence. He genuinely feared that a sudden loss of international prestige could reopen the divisions he had spent fifteen years trying to close.

This fear may well have originated in a particular early experience. On 10 August 1792, as a young officer, Napoleon had witnessed one of the climactic moments of the French Revolution, the storming of the Tuileries by the Paris crowd and the overthrow of King Louis XVI. It was the first fighting he had ever seen. He had been horrified by the subsequent massacre of the Swiss Guards and the accompanying atrocities. For Napoleon, this trauma also held a political lesson. Louis XVI had been dethroned because he had failed to show sufficient enthusiasm for a revolutionary war, and because his people had come to susepct his patriotism. Napoleon’s words to Schwarzenberg two decades later show his determination not to make the same mistake.

Significantly, when the prospect of a compromised peace appeared close during 1813 and 1814, Napoleon always used this same argument to counter it: his own rule over France would not survive an inglorious peace. He did this most dramatically on 7 February 1814. With France already invaded, his enemies offered to let him keep his throne if he renounced all of France’s conquests since the Revolution. His closest advisers urged him to accept, but he burst out: “What! You want me to sign such a treaty … What will the French people think of me if I sign their humiliation? … You fear the war continuing, but I fear much more pressing dangers, to which you’re blind.” That night, he wrote an apocalyptic letter to his brother Joseph, making it clear that he preferred his own death, and even that of his son and heir, to such a prospect.

Napoleon himself obviously believed that peace without victory would seriously threaten his dynasty. Was he right? My own view, based on researching the state of French public opinion at the time, is that he was not. The overwhelming majority of reports show the French people in 1814 as exhausted by endless war and its burdens. They were desperate for peace. Ironically, it was not concessions for the sake of peace, but his determination to go on fighting, that eventually undermined Napoleon’s domestic support. By refusing to recognize this, Napoleon did indeed cause his own downfall.

Munro Price is a historian of modern French and European history, with a special focus on the French Revolution, and is Professor of Modern European History at Bradford University. His publications include The Fall of the French Monarchy: Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette and the baron de Breteuil, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions, and The Road to Apocalypse: the Extraordinary Journey of Lewis Way (2011). Napoleon: The End of Glory publishes this month.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Did Napoleon cause his own downfall? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 7/14/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

reading list,

VSI,

very short introduction,

Europe,

French Revolution,

Bastille Day,

french literature,

UPSO,

*Featured,

John Phillips,

bastille,

university press scholarship online,

Online products,

william doyle,

and the French Revolution,

Bryant T. Ragan,

Dan Edelstein,

Homosexuality in Modern France,

Jeremy Jennings,

Jeremy Merrick,

John D. Lyons,

Keith Reader,

Le quatorze juillet,

Modern France,

Revolution and the Republic: A History of Political Thought in France since the Eighteenth Century,

the Cult of Nature,

The Marquis de Sade,

The Place de la Bastille: The Story of a Quartier,

The Terror of Natural Right: Republicanism,

Vanessa R. Schwartz,

History,

Add a tag

Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.

– Jean-Jacques Rousseau

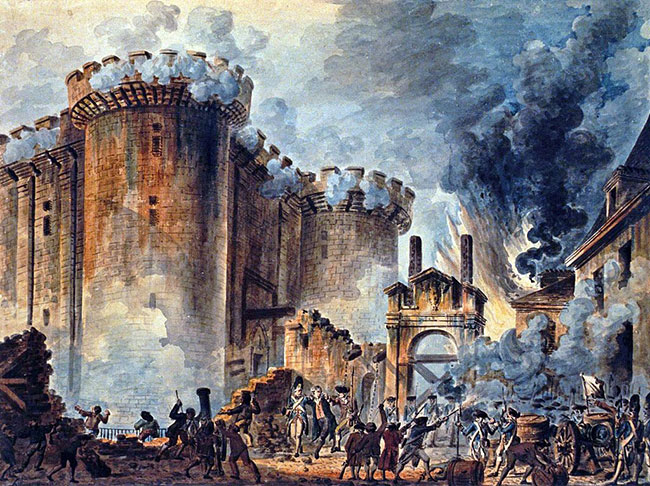

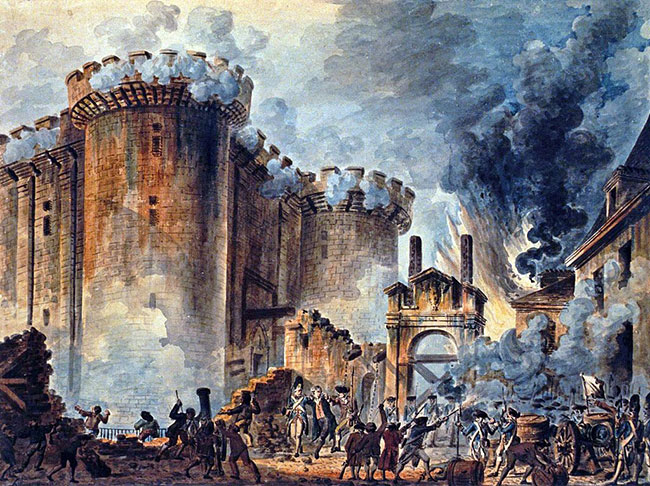

The Bastille once stood in the heart of Paris — a hulking, heavily-fortified medieval fortress, which was used as a state prison. During the 18th century, it played a key role in enforcing the government censorship, and had become increasingly unpopular, symbolizing the oppressiveness and the costly inefficiency of the reigning monarchy and the ruling classes.

On 14 July 1789, the prison of Bastille was stormed by revolutionaries. It housed, at the time, only seven prisoners — including two “lunatics” and one “deviant” aristocrat — but the storming of the fortress was not just a tactical victory. Its fall at the hands of the Parisian militia and the city’s peasants was a symbolic and ideological victory for the revolutionary cause, and became the flashpoint for one of the most tumultuous periods of European history. With the fall of the Bastille, the French Revolution had begun, which would eventually culminate in the bloody toppling of a regime which had existed for nearly 800 years. This day is celebrated across France as Le quatorze juillet, the first milestone along the road to the French Republic. In English-speaking countries, it is called Bastille Day.

To mark Bastille Day, and the 225th anniversary of the French Revolution, we’ve made a selection of informative scholarly articles free to read on the Very Short Introductions online resource and University Press Scholarship Online. Want to find out about the French Revolution, how it began, what happened, and why it is perhaps one of the most pivotal events in modern European history? Then carry on reading.

The Storming of the Bastille by Jean-Pierre Houël (1735-1813). Bibliothèque nationale de France. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Why did the French Revolution happen?

“Why it happened” in The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction by William Doyle

The years of build up to the French Revolution were full of uncertainty and confusion. Why the Revolution happened was not because of a single event, but instead it was caused by a number of developments at the end of the 1780s. This chapter provides a brief overview of these events, taking a look at how important the financial problems were in causing the initial unrest and the significance of the role of the monarchy.

What happened at the Storming of the Bastille?

“‘Thought blew the Bastille apart’: The Fall of the Fortress and the Revolutionary Years, 1789-1815“ in The Place de la Bastille: The Story of a Quartier by Keith Reader

During the late 1780s, France was suffering under a crippling economic crisis, throwing the lavish expenditures of the ruling classes and the economic incompetence of the state into bass relief. The Bastille, incredibly costly to maintain and a symbol of state oppression, had become increasingly unpopular with the masses for this reason, among others. This chapter focuses on the events which culminated in the storming and eventual ruin of the fortress, and the ensuing revolutionary years.

How has the Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen been used throughout French history?

“Rights, Liberty, and Equality“ in Revolution and the Republic: A History of Political Thought in France since the Eighteenth Century by Jeremy Jennings

The Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen (The Deceleration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen) was passed in August 1789 by France’s National Constituent Assembly. It was a cornerstone of the Revolution, and set out the rights of man as “liberty, property, security and resistance to oppression,” and is one of the most important documents in the history of human rights. Exploring the content of the Déclaration, this chapter goes on to examine how the language of rights it set out was used in key, formative moments in subsequent French history.

What were the Marquis de Sade’s politics during the French Revolution?

“Sade and the French Revolution” in The Marquis de Sade: A Very Short Introduction by John Phillips

Donatien Alphonse François de Sade, or the Marquis de Sade, was a French aristocrat, politician, and writer accused by many of political opportunism during the Revolution. He portrayed himself as both a feudal lord and the “liberator” of Bastille, when he called for revolution from his cell. He was a theatrical man with many opportunities to self-dramatize during the Revolution, making it difficult to clearly understand his political position. This chapter examines this through his thoughts and writings during the Revolution.

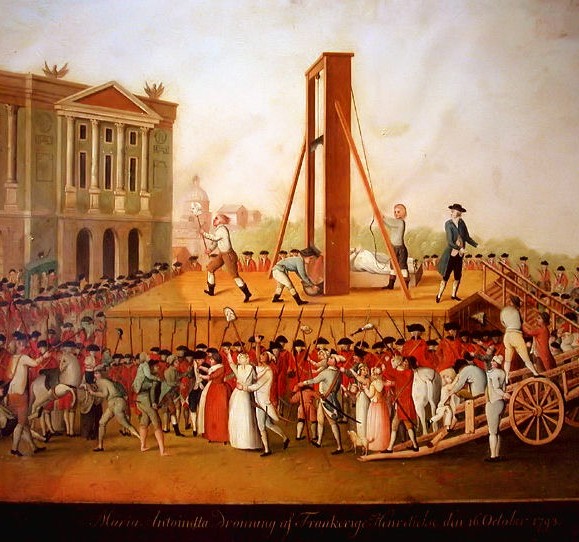

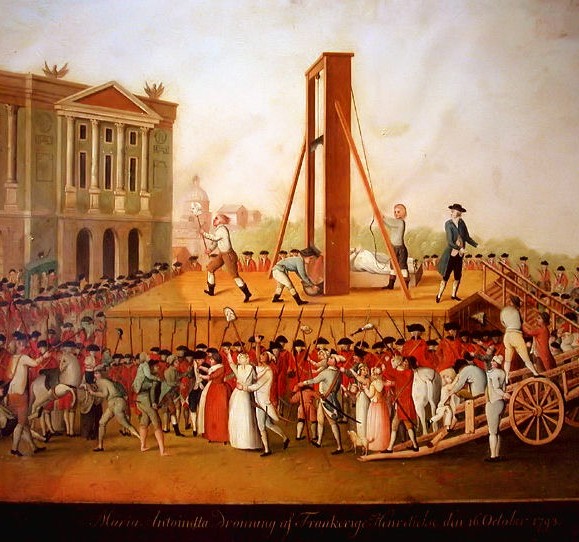

How was Marie-Antoinette represented?

“Pass as a Woman, Act like a Man: Marie-Antoinette as Tribade in the Pornography of the French Revolution“ in Homosexuality in Modern France ed. by Jeremy Merrick and Bryant T. Ragan

Marie-Antoinette, the ill-fated Austrian princess who married Louis XVI, and who met her fate under the guillotine in 1793 at the present-day Place de la Concorde, has long been a much-maligned figure of the Revolution — her name now synonymous with large wigs, “let them eat cake,” and cold indifference to the plight of the poor and disenfranchised. In this chapter, the pornographic pamphlets distributed about the Queen during the Revolution are analysed, paying particular attention to her supposed homosexuality and licentiousness, and the role this took in the anti-monarchist propaganda of the period.

What literature was inspired by the Revolution?

“Around the Revolution” in French Literature: A Very Short Introduction by John D. Lyons

Throughout the 1700s many in France grew more and more sceptical: about the absolute nature of the monarchy and around the idea that authority was established by divine providence. This chapter looks at how the literature of the time was inspired by and reflected this dissatisfaction, including Pierre Caron de Beaumarchais’s The Marriage of Figaro and The Marquis de Sade’s Justine ou les Malheurs de la Vertu.

What was the Terror?

“Off with their Heads: Death and the Terror“ in The Terror of Natural Right: Republicanism, the Cult of Nature, and the French Revolution by Dan Edelstein

The guillotine has come to embody the darker side of the French Revolution, especially during the Reign of Terror which lasted from September 1793 to July 1794. The death toll of The Terror is almost incomprehensible, with 16,500 victims meeting their ends under the guillotine. Maximilien Robespierre is the figure most closely associated with this bloody period, and yet, “in one of the more bitter ironies of history” as this chapter says, he started his career as an outspoken opponent of the death penalty. Here, the genesis of The Terror is detailed, the differences between the French and American Revolutions set out, and the concept of the hostis humani generis (enemy of humanity) introduced — an enemy who could only be met with death.

How did the French Revolution change France?

“The French Revolution, politics, and the modern nation” in Modern France: A Very Short Introduction by Vanessa R. Schwartz

The French Revolution, unlike others, managed to effect change from within, with the new government making some radical changes, even starting a new calendar, to differentiate themselves from the old regime. This chapter looks at how history and symbols were used by this new government to symbolize and mythologize their nation.

University Press Scholarship Online (UPSO) brings together the best scholarly publishing from around the world. Aggregating monograph content from leading university presses, UPSO offers an unparalleled research tool, making disparately published scholarship easily accessible, highly discoverable, and fully cross-searchable via a single online platform. Research that previously would have required a user to jump between a variety of books and disconnected websites can now be concentrated through the UPSO search engine.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A reading list on the French Revolution for Bastille Day appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Maria Donnini,

on 2/27/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

British,

Europe,

French Revolution,

new testament,

Napoleon,

testament,

*Featured,

Barbou brothers,

duodecimo,

Latin Testament of the Vulgate Translation,

Novum Testamentum Vulgatae Editionis: Juxta Exemplum Parisiis Editum apud Fratres Barbou,

Simon Eliot,

Vulgate Bible,

vulgate,

1796,

Books,

History,

Religion,

Media,

Add a tag

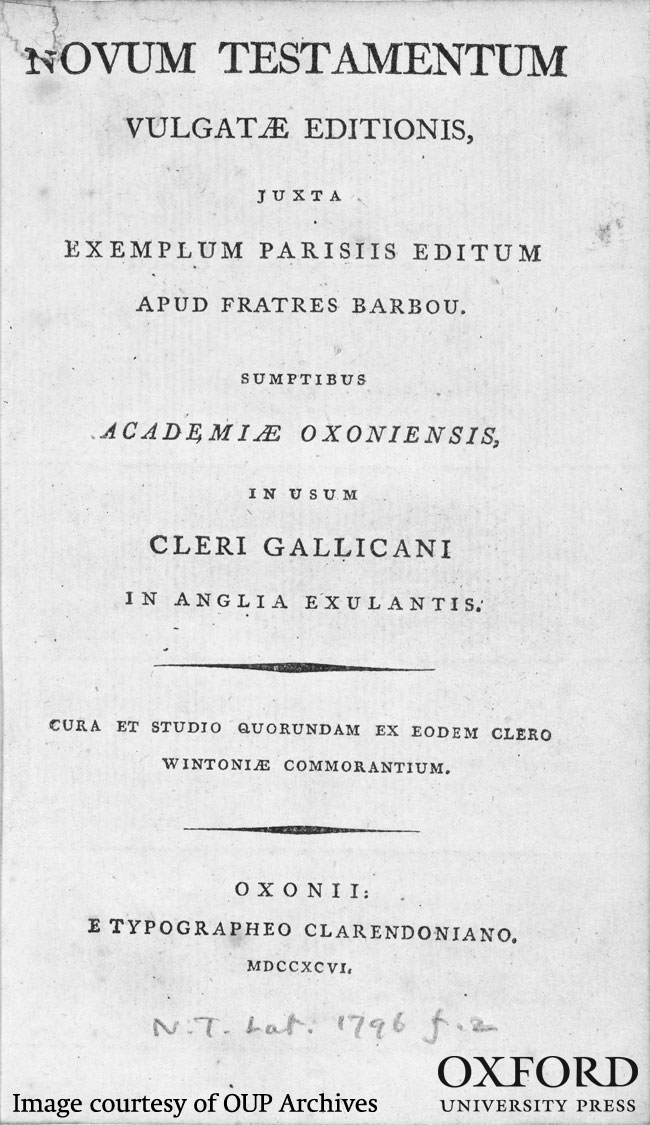

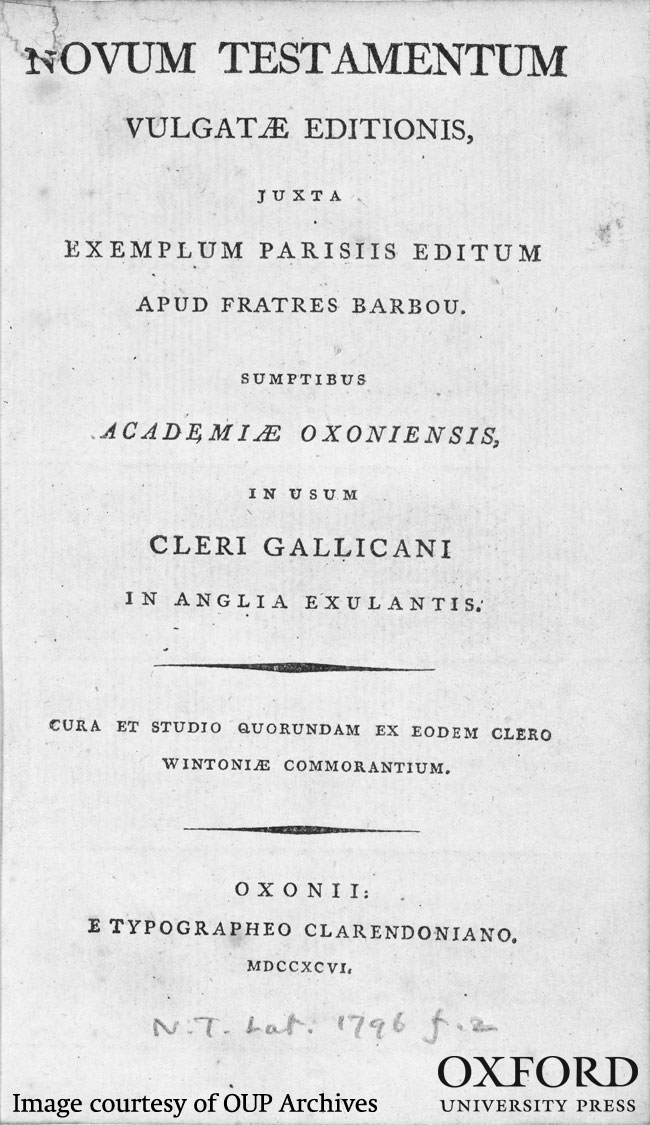

By Simon Eliot

With the French Revolution creating a wave of exiles, the Press responded with a very uncharacteristic publication. This was a ‘Latin Testament of the Vulgate Translation’ for emigrant French clergy living in England after the Revolution. In 1796, the Learned (not the Bible) side of the Press issued Novum Testamentum Vulgatae Editionis: Juxta Exemplum Parisiis Editum apud Fratres Barbou. The title page went on to declare that it had been printed at the University of Oxford for the use of French clerics who were exiled in England. This edition was based, as the title makes clear, on editions published by the Barbou brothers, which had been printed at Paris from the mid-eighteenth century onwards. This particular edition had been overseen by a number of French priests ‘living in Winchester’. The reference is to the King’s House in Winchester which, until the government converted it into barracks in 1796, was home to around 600 exiled French clergy; these were later re-housed in Reading and in Thame in the Thames valley.

A total of some 4,000 copies of this edition were printed: “That 2,000 Copies of the Lat. Vulgate Testament (besides the additional 2,000 printed by order of the Marquis of Buckingham) be forwarded to the Bishop of St . Pol de Leon to be distributed under his direction … and the remainder sold at two shillings each.”

A total of some 4,000 copies of this edition were printed: “That 2,000 Copies of the Lat. Vulgate Testament (besides the additional 2,000 printed by order of the Marquis of Buckingham) be forwarded to the Bishop of St . Pol de Leon to be distributed under his direction … and the remainder sold at two shillings each.”

Though partly an exercise in charity, it was clearly anticipated that this New Testament might also be considered a commercial proposition. The published volume appears to be a particular form of duodecimo (strictly 12o in 6s, half-sheet imposition; the paper carried a watermarked date of ‘1794’) of 473 pages with a four-page preface by the Bishop addressed to ‘Meritissime Domine Vice-Cancellarie’, in which he expressed his gratitude to the University of Oxford for its support. At the end of the text there is a brief chronological table of New Testament events, followed by an ‘Index Geographicus’. A final unnumbered leaf carries a list of errata (29 in all) which reflected a rather different approach to that adopted by the Bible Side of the Press when issuing its editions of the King James Version of the New Testament. The latter were subjected to rigorous proof reading and re-reading in order to ensure that the word of God was as free from errors as was humanly possible. This edition of a Latin text, produced in extraordinary circumstances for the consumption of mostly foreign readers, was clearly a very different kettle of fish. Additionally, in printing this edition on the Learned Side rather than the Bible Side of the Press, the Delegates culturally quarantined the production of the Vulgate text and avoided any political or religious problems that might have arisen had the privileged side of the Press undertaken it. That the very peculiar and extreme circumstances which produced this anomaly were not to be repeated was made clear 99 year later when, it having been suggested in 1895 that the Press should produce a Roman Catholic Bible, the Delegates responded that they did not ‘think it desirable that such a work should be issued with the University Press Imprint’.

Later, as the threat from Napoleonic France increased, the Press recorded certain exceptional payments in its annual accounts. These accounts included many forms of overhead costs, some a constant feature of the Press’s outgoings, such as the cost of coals and firewood (£10.17.6 in 1800) or ‘taxes to Magdalen Parish’ (£8.16.0 in the same year). Others were temporary and related to the troubled times in which they were paid. The 1805-6 accounts list the payment of a ‘Militia Tax’ of 8s6d, which went up to 17s4d in the following year. Having missed the subsequent year, the Press paid two militia rates in 1808-9 amounting to £2-7-8. In 1812-3 the rate was £1-6-0, dropping to 13s in 1813-4 before vanishing from the accounts as the threat represented by Napoleon disappeared after the battle of Waterloo.

Simon Eliot is Professor of the History of the Book in the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. He is general editor of The History of Oxford University Press, and editor of its Volume II 1780-1896.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read previous blog posts about the history of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A Vulgate New Testament printed for the use of exiled French clergy, 1796. (Bodleian, N.T.Lat. 1796 f.2, 159 x 96mm). From the History of Oxford University Press. Courtesy of OUP Archives. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post The Press stands firm against the French Revolution and Napoleon appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 9/6/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

VSI,

Europe,

Very Short Introductions,

French Revolution,

revolutions,

monarchy,

guillotine,

Reign of Terror,

bloody,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Robespierre,

1793,

french republic,

French Revolutionary Wars,

william doyle,

Add a tag

By William Doyle

Two hundred and twenty years ago this week, 5 September 1793, saw the official beginning of the Terror in the French Revolution. Ever since that time, it is very largely what the French Revolution has been remembered for. When people think about it, they picture the guillotine in the middle of Paris, surrounded by baying mobs, ruthlessly chopping off the heads of the king, the queen, and innumerable aristocrats for months on end in the name of liberty, equality, and fraternity. It was social and political revenge in action. The gory drama of it has proved an irresistible background to writers of fiction, whether Charles Dickens’s Tale of Two Cities, or Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel novels, or many other depictions on stage and screen. It is probably more from these, rather than more sober historians, that the English-speaking idea of the French Revolution is derived.

Unquestionably the Terror was bloody. Over 16,000 people were officially condemned to death, as many again or more probably lost their lives in less official ways, and tens of thousands were imprisoned as suspects, many of them dying in prison rather than under the blade of the guillotine. But the French Revolution did not begin with Terror, and nobody planned it in advance. Robespierre, so often (and quite wrongly) regarded as its architect, was a vocal opponent of capital punishment when the Revolution began. But revolutions, simply because they aim to destroy what went before, create enemies. In France there were probably far more losers than winners, and not all of those who lost were prepared to accept their fate. So from the start there were growing numbers of counter-revolutionaries, dreaming of overturning the new order. How were they to be dealt with?

After three years of increasing polarisation, it was decided to force everybody to choose by launching a war. In war nobody can opt out: you are on our side or on theirs, and if you’re on theirs, you’re a traitor. If the war goes badly, it becomes increasingly tempting to blame it on treason, and to crack down on everybody suspected of it. By the first quarter of 1793, the war was going badly. The first proven traitor to suffer official punishment was the king himself, overthrown in August 1792 and executed the following January. After that the new republic found itself on the defensive against most of Europe. The measures it took to organise the war effort, including conscripting young men for the armies, provoked widespread rebellion throughout the country. By the summer huge stretches of the western countryside were out of control, and major cities of the south were denouncing the tyranny of Paris. When news came in early September that Toulon, the great Mediterranean naval base, had surrendered to the British, the populace of Paris mobbed the ruling Convention and forced it to declare Terror the order of the day. It seemed the only way to defeat the republic’s internal enemies.

Many of the instruments of Terror were already in place. A revolutionary tribunal had been established in March, and the guillotine had first been used a year earlier, designed as a reliable, fast, and humane way of executing criminals. Now they were systematically turned against rebels. Most victims of the Terror died in the provinces, after forces loyal to the Convention recaptured centres of resistance. This was mopping up a civil war. The vast majority of them were not aristocrats, but ordinary people caught up in conflicts that they could not avoid. Naturally, however, it was high profile victims who caught the eye, especially when, in the early summer of 1794, political justice was centralised in Paris. Often called the ‘great’ Terror, these last few months actually represented an attempt to bring the process under control. By then people were so sickened by the bloodshed (for unlike hanging, decapitation did shed a lot of blood) that the main site of execution was moved to the suburbs. The emergency was in fact over, and repression had done its work. The fortunes of war had also turned, and French armies were winning again. So everybody was looking for ways to end an episode of which the republic was becoming increasingly ashamed. Eventually a scapegoat was found, Robespierre, who had too often stood up to defend the increasingly indefensible.

Terror had built up slowly, and the proclamation of 5 September 1793 merely confirmed what was already happening. But it ended quite suddenly in July 1794, when it was possible to pin the blame shared by many on one incautiously vocal figure and a handful of his henchmen. But however ruthlessly, Terror had saved the republic from overthrow. Nor should we forget that other combatant states at the time resorted to repression of their own. In 1798, 30,000 people died in the great Irish rebellion, in a population only a sixth that of France. The British monarchy could be every bit as ruthless as the French republic, when it had to be.

William Doyle, Professor of History, University of Bristol and author of The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction and Aristocracy: A Very Short Introduction. Read Professor Doyle’s post on aristocracy here.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Execution of Marie Antoinette in 1793, [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons; (2) “Enemies of the people” headed for the guillotine during The Reign of Terror [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

The post The Reign of Terror appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 1/25/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

Literature,

poems,

songs,

French Revolution,

stanza,

robert burns,

Burns,

Humanities,

Burns Night,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Burns suppers,

Professor Irvine,

Robert P. Irvine,

burns’s,

Add a tag

By Robert P. Irvine

As we sit down to enjoy our Burns Suppers on Friday, it is worth pausing to ask ourselves just how well we know some of the songs and poems that are a feature of the occasion. Editing and presenting a selection of his texts in the order in which they were published, taking as my copy-text the version of the poem or song published on that occasion, has given me many new insights into the original contexts of Burns’s work. The advantage of this procedure is that it invites the modern reader to think about the Burns encountered by his first readers, the public Burns of the 1780s, 1790s and later, helping us (I hope) to bypass some of the cultural baggage that has accumulated around the poet and to come at his work afresh.

The results of this can occasionally be surprising. Let me take one example: ‘Bruce’s Address to his troops at Bannockburn’, often known as ‘Scots, wha hae’. This song was first published, anonymously, in the London daily Morning Chronicle for 8 May 1794. Under the owner-editorship of James Perry (born Pirie, in Aberdeen) this was the widely-read national journal of the Charles James Fox’s party in the Commons, bitterly opposed to the government of William Pitt and sympathetic to the French Revolution. Simply putting it in this context directs the reader to its original meaning, as a song celebrating not medieval Scottish resistance to English overlordship, but the contemporary mobilisation of the French people in the levée en masse in response to the new coalition ranged against their new republic. But the poem we find in the Morning Chronicle is not the one we think we know. It begins:

The results of this can occasionally be surprising. Let me take one example: ‘Bruce’s Address to his troops at Bannockburn’, often known as ‘Scots, wha hae’. This song was first published, anonymously, in the London daily Morning Chronicle for 8 May 1794. Under the owner-editorship of James Perry (born Pirie, in Aberdeen) this was the widely-read national journal of the Charles James Fox’s party in the Commons, bitterly opposed to the government of William Pitt and sympathetic to the French Revolution. Simply putting it in this context directs the reader to its original meaning, as a song celebrating not medieval Scottish resistance to English overlordship, but the contemporary mobilisation of the French people in the levée en masse in response to the new coalition ranged against their new republic. But the poem we find in the Morning Chronicle is not the one we think we know. It begins:

Scots, wha hae wi’ Wallace bled,

Scots, wham BRUCE has aften led,

Welcome to your gory bed,

Or to glorious victorie!

That word ‘glorious’ is not in the version of the song we sing today. Where did it come from? Well, Burns added two syllables to the last line of each of his verses to make them fit a different tune, one suggested by his publisher, George Thomson. Burns liked this revised version, and sent it in manuscript to some of his friends. This was the song that found its way to the Morning Chronicle; it was also republished from that source in cheap pamphlets later in the decade. So if we are interested in the Burns that radical or working-class readers were reading in the 1790s, we need to read this version of the song, with the longer line ending its stanzas, and sung to a different tune, rather than the version that has come down to us from Burns’s first draft.

Or take the democratic anthem ‘A man’s a man for a’ that’, sung so movingly by Sheena Wellington at the reconvening of the Scottish Parliament in 1999. This was first published, again anonymously, in the Glasgow Magazine for August 1795, like the Morning Chronicle a radical publication. Its famous opening stanza is as follows:

Is there, for honest poverty

That hangs his head, and a’ that;

The coward-slave, we pass him by,

We dare be poor for a’ that!

For a’ that, and a’ that.

Our toils obscure, and a’ that,

The rank is but the guinea’s stamp,

The man’s the gowd for a’ that.

Yet this stanza is missing from the poem in the Glasgow Magazine. Why should this be? We have no manuscript evidence that Burns ever wrote a version of this poem without this stanza, on which the magazine might have based their copy. But a clue as to the reason for its omission might lie in that phrase, ‘coward-slave’. Burns here, as elsewhere, uses the term ‘slave’ to mean ‘one who submits to tyranny’, who does not fight for his political liberty: a meaning familiar from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century political rhetoric. But the late eighteenth century had seen the rise of a campaign against slavery in quite different sense: the slavery endured by Africans in Britain’s West Indian colonies. The radicalism of the Glasgow Magazine included adherence to such modern causes. The same issue that includes Burns’s poem comments on recent complaints about the disruption that war with France was causing colonial trade; but, asks the magazine, ‘of what consequence are the present disappointments of the West India merchants, compared with the miseries of millions of Africans, whom their infamous trafic has reduced to slavery […]?’ It is possible that, in this context, Burns’s reference to ‘coward-slaves’, culpable in their own subjection, looked out-of-place, perhaps out-of-touch with current radical priorities, and the editors decided simply to cut the stanza that contained it.

The Glasgow Magazine version is also the origin of a variant in the opening line of the third (or fourth) stanza, which in all other versions reads, ‘A prince can make a belted knight’. In the magazine, this is ‘The king can make a belted knight.’ Again, this matters if we are interested in the song being read by its first readers, in this case Scottish radicals in the 1790s. But this song is clearly the product of a radicalism that cannot simply be identified with Robert Burns. It is likely that the editors substituted ‘The king’ for ‘A prince’ to make the song more pointedly sceptical towards the British monarchy in particular, rather than monarchy in general, than the version which came to them. We are familiar with the pressure from the government under which Burns worked as soon as he became an employee of the crown. But here is an instance where Burns’s work seems to have censored not by the state, but by his political allies, for whom ‘A man’s a man for a’ that’ as Burns wrote it was perhaps not quite radical enough, or radical in a slightly old-fashioned way. In this case as in so many others, returning Burn’s poems and songs to the versions and context of their first publication can help us qualify and complicate the simplifying versions of his work that have gained currency over the years.

Robert P. Irvine has written on Jane Austen and is the editor of The Edinburgh Anthology of Scottish Literature, 2 vols. (Kennedy and Boyd, 2009), R.L. Stevenson’s Prince Otto for the New Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Robert Louis Stevenson (forthcoming), and Selected Poems and Songs (OUP, 2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: By William Hole R.S.A. (The Poetry of Burns, Centenary Edition) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post A fresh look at the work of Robert Burns appeared first on OUPblog.

Revolution Jennifer Donnelly

Revolution Jennifer Donnelly

For some reason when everyone was raving about this book my main thought was "probably not for me." Something about the way it was described made me believe that it was probably awesome, but... just not for me.

I can't remember what finally made me pick it up. Just so I could say I had read it? Possibly.

I loved it. I really did.

Basic plot-- Andi's family falls apart after the death of her little brother. Andi blames herself and has fallen into a very self-destructive pattern. Her father wasn't around that much before Truman died, but he's officially left town and is now with his lab assistant. Andi's mother has gone crazy.

When her father finally learns that Andi's about the fail out of school and won't graduate, he comes back to Brooklyn to drag her to Paris so she can write her senior thesis outline-- her one chance at graduation. He also checks her mother into a mental hospital.

Andi's father is in Paris to do genetic testing on a heart that may or may not belong to Louis-Charles, the youngest son of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. Andi's researches her thesis on the music of Amade Malherbeau and his influence on later musicians to the modern day. While Paris is the best place to research Malherbeau's life (it's where he lived and composed) it doesn't get Andi's mind off things. Louis-Charles has Truman's eyes.

And then Andi finds a diary of Alex, a street performer who was Louis-Charles's companion and caught up in the horrors of the Revolution...

I like that, even though it's two stories in one, the focus stays on Andi. I was also wondering how the two were going to come together. How they did was... unexpected, but I liked it.*

Andi is so unpleasant, but the portrait of someone torn about by grief and guilt is so well done. I loved the solace she found in music and the advice of her guitar teacher.

Also... finding solace in classical guitar? Nice choice.

OH! And I looooooooooooooooooooooooved how human Marie Antoinette was. I haven't read a lot of fictional accounts of the French Revolution, so I don't have a huge basis for comparison, BUT, in popular culture she's portrayed as such a monster. I loved seeing a portrait of her as a mother and person.

I didn't find Alex's story as gripping, but I loved how taken Andi was with it and I think that if we hadn't been able to read what Andi was reading, we would have really lost what Andi was feeling and how important Alex became to her.

I was utterly engrossed in the story, and even though it's pretty lengthy (472 pages) I couldn't put it down and read it quickly (not that it's a quick read, just that when you read it CONSTANTLY...)

I'm not sure how I feel about the epilogue... I think I needed something more immediate and less nice, BUT overall, yes, this is a wonderful book and I'll add my voice to everyone else's.

*Slight spoiler-- I totally thought that Alex would end up being Malherbeau and that Malherbeau's big mystery was that he was really a she. Glad that I was wro

Revolution by Jennifer Donnelly. Delacorte, 2010

(review copy provided by publisher)

Revolution kept me turning pages and dialing up the audiobook, nonstop, until I finished. It is one of the most intriguing books I read in 2010.

Andi's little brother, Truman, has been killed (the reader does not know how or why) and she believes it is her fault. She wears a key that belonged to him around her neck on a red ribbon. Is it a tender remembrance or is it penance? Her mother has sunk into deep grief and compulsively paints portraits of the boy on the walls of their home, neglecting everything and everyone else.

When her father, a world famous scientist and absentee father, learns that Andi is about to flunk out of her private high school, he takes her to Paris where he is participating in a scientific examination of DNA of a preserved heart, reputed to be that of the dauphin, Louis-Charles, the son of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

Coincidently (or maybe not) Andi discovers the diary of a young woman, hidden in an antique guitar case. Alexandrine Paradis, the author of the diary, was the companion of the same Louis-Charles. Andi is caught up in the events of the French Revolution as she reads the diary and Alexandrine's story merges with Andi's causing Andi (and the reader) to question what is really happening. Is there really a fantastical connection to the events in the past or is her mind reacting to medication and to her brother's death?

In the present, Andi meets a young cab driver and musician named

Virgil (one of many allusions to Dante's

Divine Comedy which is also quoted at the start of each section.) He shares her passion for music and her interest in him gives her a lift from her depression and an anchor in the present.

Still, her fury with her father, her depression and thoughts of suicide are painful. As a reader, I wanted to reach into the story and stop her hand as she downs the prescription anti-depressants that are probably exacerbating those thoughts. Donnelly does provide some well timed, comic relief through Andi's best friend in the States, Vijay Gupta, who is seeking input from world leaders for his senior thesis

As gifted musician and guitarist herself, Andi has chosen an 18th century composer, Amadé Malherbeau, for her senior thesis. She is supposed to be researching him while in Paris. This story is infused with music theory and music history, rap, and classical guitar. Even though Malherbeau is fictional, Donnelly provides such a solid musical grounding for him that readers will want to believe in his historical existence.

Donnelly truly captures Revolutionary Paris and the Paris of today. The officious library clerk that Andi encounters at the library/archives is the quintessential French bureaucrat. T

REVOLUTION by Jennifer Donnelly Bloomsbury hbk £10.99

Jennifer Donnelly’s A GATHERING LIGHT was a genuine crossover novel which delighted readers of all ages and was one of the first books published on the teenage lists genuinely (and quite rightly) to make its mark on the literary landscape. It was based on a true story, but took off from the original facts to create a time and a place and above all characters, with whom readers could happily engage.

Now Donnelly has written a novel that’s quite different but which is also one that transcends its genre. My copy is a proof so I don’t know whether the author’s introduction will be there in the final book, but it’s a fascinating account of how she came to write this novel. Made very vulnerable by the fact that she had a young daughter of her own at the time, she describes vividly how horrified and chilled she was to read of the fate of Marie Antoinette’s son, Louis, during and after the imprisonment and execution of his mother at the start of the French Revolution.

This feeling has grown into a book which combines three kinds of novel: a time-slip tale of sorts, a historical novel and the thing that somehow Americans know how to do supremely well: the personal odyssey of a teenage girl who has suffered a great tragedy in her own life.

Andi writes in the first person and we believe her completely. She’s a talented musician but is troubled by many things. Her parents have divorced. Her younger brother is dead and she feels great guilt about how this happened. Her mother is at the end of her tether. She has a marvellous friend called Vijay and a good teacher too, but she’s in a terrible state when the novel opens. We don’t, as sometimes happens in teenage novels, want to tell her to get real and pull her socks up. Rather, we’re drawn into her world because Donnelly has made her so real, so present, and above all, has given her so engaging a voice. We are worried for her, we feel for her, we sympathize with her and when she goes to Paris to be with her father and pursue research on a French composer of the 18th century called Amadé Malherbeau, we know that the adventures are about to begin.

Andi finds something that leads her back in time. Interspersed with her voice is an account of those days written by a young musician/performer of the time, and Andi becomes obsessed with finding out more. The adventures then happen, thick and fast and at first I wasn’t a hundred percent sure of the time-slip element but Donnelly pulls it off with some bravura and by the end, I was convinced. The dénouement is marvellously satisfying without being a cop-out. This is such a well-written, carefully structured and intricately organized book that you race through it longing to know more and even more. Along the way, you also learn a great deal about a side of the French Revolution that isn’t terribly well known. The musical knowledge displayed in the novel is awesome and it has its own playlist printed at the front of the book which will enchant anyone who cares to listen to the tracks recommended. But its greatest triumph is in bringing to the pages of teenage fiction a really terrific heroine whom we grow to care for and admire. I hope Jennifer Donnelly is already half way through writing her next book because I can’t wait to read it.

A TALL STORY by Candy Gourlay. David Fickling hbk

I know I’m a bit late coming to write about this book. It’s been generally admired wherever I’ve seen it reviewed, but because I loved it, I think I ought to add my bit to the chorus of approval. Candy is a member of the SAS but I’ve never met her. From the evidence of this novel, not only is she a good writer but also someone whose own warmth and generosity comes through in her book. It’s the story of a girl from the Philippines living in London, (and by coincidence, also called Andi) longing to be on the basketball team at school, and about to meet a half brother from the Philippines. He

By:

Becky Laney,

on 3/17/2010

Blog:

Becky's Book Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

YA Fiction,

series,

YA Historical Fiction,

YA Romance,

Carolyn Meyer,

2010,

French Revolution,

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt,

borrowed book,

Add a tag

Bad Queen: Rules and Instructions for Marie-Antoinette by Carolyn Meyer. 2010. [April 2010] Harcourt. 420 pages.

The empress, my mother, studied me as if I were an unusual creature she'd thought of acquiring for the palace menagerie. I shivered under her critical gaze. It was like being bathed in snow.

I was not disappointed in Carolyn Meyer's latest book. This historical novel is based on the rise and fall of Marie Antoinette. It is the story of the French Revolution and the monarchs that fell as a nation revolted.

Each chapter is a numbered rule. So you'll see advice such as:

"You must become fluent in French"

"You are born to obey, and you must learn to do so"

"Never behave in a manner to shock anyone"

"An outward display of emotion violates all the rules of etiquette"

"You cannot change the rules of etiquette"

"It is not your role to defy accepted fashion"

"You must control your spending"

Chapters, of course, don't have to be titled anything in a book. But in this case I thought it was a nice touch. It helped set the tone of the book, in my opinion. (I also loved that the chapters were quick!) Though Marie Antoinette is given plenty of advice--by her mother and her Austrian family, by her husband's family, by royal advisers, etc. Marie doesn't always follow it! She definitely had a strong will and didn't like being told what she could and couldn't do. Especially when some of the rules didn't make much sense to her. Why couldn't she dress the way she wanted? Why did everything have to be done a certain way, the way it had

always been done?

The Bad Queen is told in first person through the eyes of Marie Antoinette. Towards the end of the book, as the family's fate becomes more certain, when she knows her days are numbered and the end will be anything but pretty, the narration switches to Marie's daughter.

Readers get a behind-the-scenes look at what it's like to be royalty, what it's like to live in luxury, what it's like to be someone that everyone loves to hate.

I found this one to be a compelling read. Even though I knew what was coming, I just had to keep reading!

This isn't the first time Carolyn Meyer has written about royalty. There is

Anastasia: The Last Grand Duchess;

Kristina, The Girl King;

Doomed Queen Anne;

Mary, Blood Mary;

Beware, Princess Elizabeth; and Patience, Princess Catherine; and

Duchessina: A Novel of Catherine de Medici. I've read and enjoyed them all.

What do you think of the cover of this one?

© Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

A total of some 4,000 copies of this edition were printed: “That 2,000 Copies of the Lat. Vulgate Testament (besides the additional 2,000 printed by order of the Marquis of Buckingham) be forwarded to the Bishop of St . Pol de Leon to be distributed under his direction … and the remainder sold at two shillings each.”

A total of some 4,000 copies of this edition were printed: “That 2,000 Copies of the Lat. Vulgate Testament (besides the additional 2,000 printed by order of the Marquis of Buckingham) be forwarded to the Bishop of St . Pol de Leon to be distributed under his direction … and the remainder sold at two shillings each.”

What could philosophy have to do with odors and perfumes? And what could odors and perfumes have to do with Art? After all, many philosophers have considered smell the lowest and most animal of the senses and have viewed perfume as a trivial luxury.

The post Perfumes, olfactory art, and philosophy appeared first on OUPblog.

Novelists are used to their characters getting away from them. Tolstoy once complained that Katyusha Maslova was “dictating” her actions to him as he wrestled with the plot of his last novel, Resurrection. There was a story that after reading Mikhail Sholokhov’s And Quiet Flows the Don, Stalin praised the work but advised the author to “convince” the main character, Melekhov, to stop loafing about and start serving in the Red Army.

The post An educated fury: faith and doubt appeared first on OUPblog.

The very look and feel of families today is undergoing profound changes. Are public policies keeping up with the shifting definitions of “family”? Moreover, as the population ages within these new family dynamics, how will families give or receive elder care? Below, we highlight just a few social changes that are affecting the experiences of aging families.

The post When aging policies can’t keep up with aging families appeared first on OUPblog.