by Addy Farmer

I wonder if you can summon up the image of a glorious sunset inside your head? Can you capture the nuance of colour in the sky, the shape of the sun, the texture of the scene? I'll leave that one with you for now.

This ability is sometimes referred to as 'the mind's eye':

The phrase "mind's eye" refers to the human ability to visualise i.e., to experience visual mental imagery; in other words, one's ability to "see" things with the mind.

I have always had this ability and I have always assumed that everyone else was able to do the same. It turns out after a quick delve into history, that this is not the case.

A Brief Peer into Visual imagination. In an interesting

blog summary I found:

"There was a debate, in the late 1800s, about whether "imagination" was simply a turn of phrase or a real phenomenon. That is, can people actually create images in their minds which they see vividly, or do they simply say "I saw it in my mind" as a metaphor for considering what it looked like?

Francis Galton, a nineteenth century psychologist, gave people some very detailed surveys, and found that some people did have mental imagery and others didn't. The ones who did had simply assumed everyone did, and the ones who didn't had simply assumed everyone didn't."

|

| Francis Galton - close your eyes and then try and recall the detail of his lovely sideburns |

Recently, a new word has been added to the medical lexicon,

Aphantasia, which brings us back to that sunset. The University of Exeter has taken up the work of Galton and come up with a new study.

She ... realised that her ability to conjure a mental picture differed from her peers during management training in her 20s. She said: “We were told to ‘visualise a sunrise’, and I thought ‘what on Earth does that look like’ – I couldn’t picture it at all. I could describe it – I could tell you that the sun comes up over the horizon and the sky changes colour as it gets lighter, but I can’t actually see that image in my mind.”

Dame Gill has a successful career and does not feel hindered by her lack of a “mind’s eye”. But she said: “I became more aware of it when my mum died, as I can’t remember her face. I now realise that others can conjure up a picture of someone they love, and that did make me feel sad, although of course I remember her in other ways. I can describe the way she stood on the stairs for a photo for example, I just can’t see it.”

What does this mean for readers? Beyond being presented with images in a book full of pictures, is a reader hampered by an inability to conjure images in her head? Crucially - does it put someone off reading non-illustrated texts when they are older? In the Exeter summary, a bookshop worker says

Niel works in a bookshop and is an avid reader, but avoids books with vivid landscape descriptions as they bring nothing to mind for him. “I just find myself going through the motion of reading the words without any image coming to mind,” he said. “I usually have to go back and read a passage about a visual description several times – it’s almost meaningless.”

And is there a knock on effect for writers? For example, does a limited or non-existent visual imagination stop a writer, wether knowingly or not, from writing longer more descriptive stories. Might a writer avoid writing, say, a ghost story, where creating atmosphere is crucial? I know that there are children's writers out there who have this condition to some degree - I wonder what they think?

|

| Okay - which part of my fevered brain did this come from? |

How Good is your Visual Imagination?

I love a quiz and the BBC have helpfully posted a way of finding out where you come on the visual imagination register.

Give it a go!

Clearly there are some cases where you may benefit from a bit of brain re-training. In his book,

The Mind's Eye,

Oliver Sacks talks about a case of, "alexia sine agraphia" which means the inability to read while retaining the ability to write. The patient was a crime writer called Howard - how would he ever write another detective story if he couldn't read his own plot notes? In a novel (sorry) approach, he trains his brain to understand what he sees by tracing the outlines of words with his tongue. Weird but true or as Sacks puts it, "Thus, by an extraordinary, metamodal, sensory-motor alchemy... he was, in effect, reading with his tongue." And so he goes on to write another novel.

Consider this, the strangest of facts: your thoughts, memories and emotions, your perceptions of the world, and your deepest intuitions of selfhood, are the product of three pounds of jellified fats, proteins, sugars and salts – the stuff of the brain and as tough as blancmange. It's absurd, wonderful and terrifying. The Guardian Review of The Mind's Eye by Oliver Sacks

The brain can do remarkable things. I am not advocating licking your words to find a deeper meaning (feel free) but maybe shaking ourselves out of our 'normal' way of thinking may give a different perspective or unlock a way of writing you had not considered before.

|

| Beware moving vehicles |

A Bit of Brain Re-training

Pick something simple at first, such as a plain mug or even a small piece of blank paper. Until you get good at this, stay away from complex items such as car keys or anything that has lots of colours, designs or textures.

Sit down and get yourself comfortable (not too comfy). Put the object on the table in front of you. Lean over where your face is two or three feet from the object. Now with your eyes open, look at the object. Study it in detail. Notice any glare from the light in the room. Pay attention to its texture. Is it smooth or is it coarse? Study it and get as many details as you can.

Now close your eyes. In your mind's eyes, picture the object as if you were still looking at it. If you have a rough time at first, just make something up. Try to get as many details correct as you can. Now open your eyes again and look again at the object. Study it in great detail for a few moments.

Keep going back and forth like this for five or ten minutes. Play around with the exercise a couple times a day to become good at this skill.

As you improve, start playing around with more advanced visualizations. Imagine what a room would look like from a top corner. Image what a city would look like from a tall building. The whole idea is to be able to visualize anything that exists – to be able to hold a good, clear and detailed picture in the mind's eye. As an aside, the most common mistake people make with this is not making the visualization clear and detailed.

BUT this simply does not work for everyone. One person with a very limited visual imagination who wanted to improve this skill tried this:

1. Explicit imagery practice. He drew simple shapes, like a square or a ball, then stared at the shape, closed his eyes, seen the shape for as long as it stayed visualisable, opened his eyes to refresh, repeat. But he only retained a brief after-image.

2. Staying in visualization situations. When he found himself in the just-before-sleep state, he stayed there for a while and played with imagery. But he reported no increase in his range of visualisation states or ability to visualise.

3. Object drawing. He tried 3D constructions of blocks and tried drawing them from different angles on paper. But there was no actual imagery or mental rotation involved.

Are Artists Natural Visual Imaginers?

Are there any artists who CANNOT conjure up a sunset? Presumably, actual haunted houses, the Moon, a jungle clearing to give just a few examples, are not always within easy reach to copy but the image can be captured in an artist's head like a writer's voice is captured on the page. I do wonder how far illustrators 'see' picture books in their heads? Is it just broad brush to begin with, then the details come with the image on the page?

In an interesting interview Jim Kay explains how he uses models for his work (presumably for consistency as well as a means of creating a beautiful image).

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-34448224

Imagination Plus Experience

Back to that sunset. I find that when I try and visualise it, it is not a crisp photographic vision but more a feeling or approximation of one. For me it is not an identical process. There seems to be a fuzziness in the border between the visible and the conjured. I like to believe that my mind's eye alone is able to colonise the story landscape, mastering and portioning, fixing places and deepening the scene. But is this necessarily so?

What can deepen writing of course is experience. Actually going somewhere and using your senses can enhance your story so that your readers really feel what you feel. So, writing a night scene could be enhanced by actually going outside and feeling the cold and hearing the owls and sniffing the air, well you get the idea. It's not just the visual but the smell, touch, feel of the night. Which is all great if you don't have a scene in space.

|

| Marcus Sedgewick talked about falling in a ditch full of snow whilst researching and transferring the experience of gasping cold into his writing. |

There are of course heaps of writers out there who write without the joy of the mind's eye (and it is a joy to me) and still have the joy of writing. Just as there are writers who do not experience everything in order to write well about it.

Perhaps the more interesting questions which remain are about how the visual imagination or lack of it, might impact on the individual reader and how this might limit her engagement with a text. Or in the case of a writer how this might limit their range of writing.

Whatever kind of writer we are, we should be sponges. We have to suck up life, shlurp (?) up conversations and read, read, read until we are rubbing our spongy eyes. Whether these stories materialise as something like a film or photographs or a voice in your head or a lickable page, I suppose it doesn't matter. In the end, the stories will come and we will write them.

So you've come up with a blurb… what’s the recipe? Take an air of mystery, a sense of character, add a pinch of place and a little pace and mix all together so whoever picks up the book, senses the heady whiff and tastes adventure before he or she even takes a bite… (and thinks ‘I must have this book in my life. Off to the till I go!’)

If only! In a very short space with the average person’s very short attention span, we have to capture the buyer. And different writers will produce widely different blurbs but all blurbs have the same function – to convince a bookshop customer to buy the book they have in their hands.

So what are the basic concepts of a blurb?

– they are short

– they tend to have attention-grabbing words

– they use active rather than passive voice

– they tend to pose questions

– they might end with an ellipsis (…) so the reader has to imagine an outcome.

Other factors to consider:

– Who is the book being marketed to? The blurb must speak directly. A blurb for a teenage reader will be very different to one on a picture book bought by an adult to read to a child.

– What is the most interesting aspect of your book? Is it the character, the setting, the moral conflict? As we emerge from the fog of having written the book, we often can’t find an aspect to focus on. Get a friend to give you another crisp slant on the story with a few phrases and words.

– Make a list of words that give insight into the story. Find exciting synonyms that evoke atmosphere – replace ‘scared’ with ‘terrified’, ‘lonely’ with ‘desolate’, ‘hiding’ with ‘lurking’, ‘very’ cold with ‘murderously’ cold (see below). Okay this is ABC stuff for a writer

– Never summarize the story. You want to keep the reader guessing.

– Perhaps find a particular phrase or piece of dialogue in the story to use as a tagline.

– Don’t introduce too many characters. Don't confuse.

Marcus Sedgewick’s blurb for his book, Revolver, ticks all the boxes.

‘It’s 1910. In a cabin north of the Artic Circle, in a place murderously cold and desolate, Sig Andersson is alone.

Except for the corpse of his father, frozen to death that morning when he fell through the ice on the lake.

The cabin is silent, so silent and then there’s a knock at the door

It’s a stranger, and as his extraordinary story of dust and gold lust unwinds, Sig’s thoughts run more and more to his father’s prized possession, a Colt revolver, hidden in the storeroom.

A revolver just waiting to be used …’

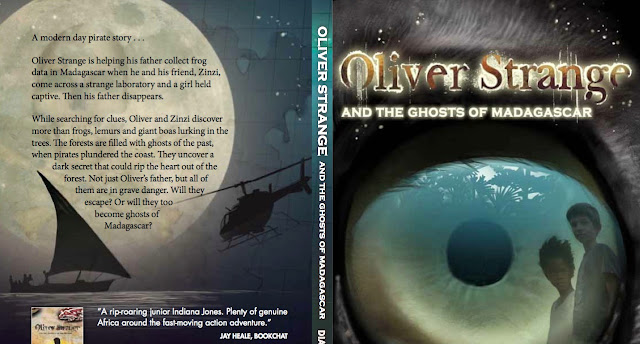

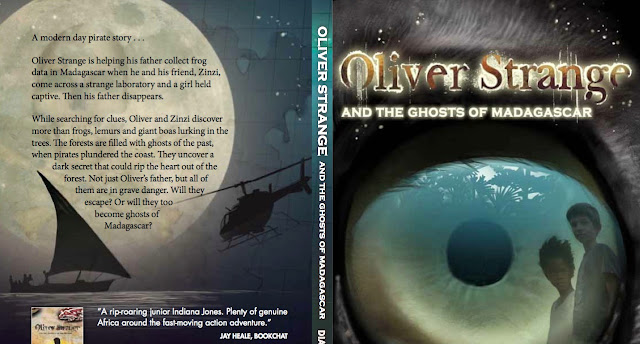

Why am I so blurb obsessed? Because I’ve just written one for my latest book, Oliver Strange and the Ghosts of Madagascar and have fallen into and have tried to drag myself out of all the pitfalls – which included making reference to the ‘place du diable’, the place of the devil, which works in the context of the entire book but not in a blurb where someone might think the book is about devil worship!

Here’s the final result (cropped to make it legible) for a mid-range book… easy language, questions, quite different to a teenage novel, but should I have started with the tagline: ‘A modern day pirate story…’ ? I’m not sure.

If you have any blurbs to share – your own, or a brilliant one you’ve come across, please put them up or share any other recipe tips for a ‘tasty’ blurb.

www.diannehofmeyr.com

That is a very good blurb, Dianne! And your post is most interesting. So many books are actually spoiled by the blurb. You'd be amazed how often thrillers have a vital thing in the blurb that SHOULD NOT BE REVEALED!!

Nice article, thanks for the information.

When I moved into fiction publishing, I remember my first task was to write blurbs for our new list. I thought it was the best part of my job ever - until I'd had to write about thirty in one week. Since then, I try and avoid blurbs...or I find mine becomes a "life spiralling out of control..."

30 in one week! I'd collapse. It took me days to write ONE! I find them VERY hard. Maybe copywriters who work in the ad industry might make good blurb writers but writers are programmed to tell a story over a long period of time so to write a blurb is alien to us. To write 30 would be a nightmare!

And yes how many blurbs give away just the line they shouldn't...

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

Great post, Dianne.

Blurbs are so important because it is often the blurb, the cover image and the first couple of lines that make people decide which book to read. It should make them desperate to find out more.

I also think writing a blurb is a great way to make sure you know what your story is all about - what matters most - when you are writing it or even before you begin!

As well as asking questions I think a blurb should also mention the main character, usually by name but not always. I agree with Adele, it should never reveal too much.

This comment has been removed by the author.

I think writing a blurb before I begin even writing the story would totally freak me out, Linda! But then I'm a hopeless planner.

I agree with Linda. Either at the beginning, or later if I'm feeling a bit uncertain about the story, I'll try and visualise the cover of the finished book and write a blurb for it. It sounds daft but it really helps!