new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Neal Porter Books, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Neal Porter Books in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 9/11/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

2016 biographies,

Reviews,

biographies,

Roaring Brook,

Best Books,

middle grade nonfiction,

Candace Fleming,

macmillan,

Neal Porter Books,

middle grade biographies,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 middle grade nonfiction,

Add a tag

Presenting Buffalo Bill: The Man Who Invented the Wild West

Presenting Buffalo Bill: The Man Who Invented the Wild West

By Candace Fleming

A Neal Porter Book, Roaring Book Press (a division of Macmillan)

$19.99

ISBN: 9781596437630

Ages 9-12

On shelves September 20th

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how we present history to our kids. Specifically I was thinking about picture book biographies and whether or not they’re capable of offering a nuanced perspective on a person’s complicated life. Will we ever see an honest picture book biography of Nixon, for example? In talking with a nonfiction author for children the other day, she asked me about middle grade books (books written for 9-12 year olds) and whether or not they are ever capable of featuring complicated subjects. I responded that often they’re capable of showing all kinds of sides to a person. Consider Laura Amy Schlitz’s delightful The Hero Schliemann or Candace Fleming’s The Great and Only Barnum. Great books about so-so people. And Candace Fleming… now there’s an author clearly drawn to historical characters with slippery slidey morals. Her latest book, Presenting Buffalo Bill is a splendid example of precisely that. Not quite a shyster, but by no means possessing a soul as pure as unblemished snow, had you asked me, prior to my reading this book, whether or not it was even possible to write a biography for children about him my answer would have been an unqualified nope. Somehow, Ms. Fleming has managed it. As tangled and thorny a life as ever you read, Fleming deftly shows how perceptions of the American West that persist to this day can all be traced to Buffalo Bill Cody. For good or for ill.

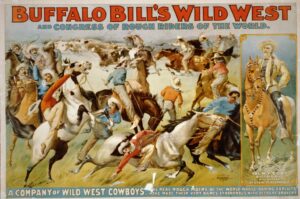

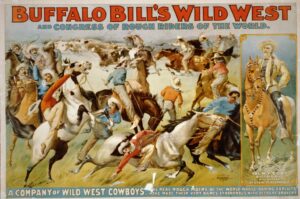

What do you think of when you think of the iconic American West? Cowboys and sage? American Indians and buffalo? Whatever is popping up in your head right now, if it’s a stereotypical scene, you’ve Buffalo Bill Cody to thank for it. An ornery son of a reluctant abolitionist, Bill grew up in a large family in pre-Civil War Kansas. Thanks to his father’s early death, Bill was expected to make money at a pretty young age. Before he knew it, he was trying his luck panning gold, learning the finer points of cowboy basics, and accompanying wagon trains. He served in the Civil War, met the love of his life, and gave tours to rich Easterners looking for adventure. It was in this way that Bill unwittingly found himself the subject of a popular paperback series, and from that he was able to parlay his fame into a stage show. That was just a hop, skip, and a jump to creating his Wild West Show. But was Bill a hero or a shyster? Did he exploit his Indian workers or offer them economic opportunities otherwise unavailable to them? Was he a caring man or a philanderer? The answer: Yes. And along the way he may have influenced how the world saw the United States of America itself.

So let’s get back to that earlier question of whether or not you can feature a person with questionable ethics in a biography written for children. It really all just boils down to a question of what the point of children’s biographies is in the first place. Are they meant to inspire, or simply inform, or some kind of combination of both? In the case of unreliable Bill, the self-made man (I’m suddenly hearing Jerry Seinfeld’s voice saying to George Costanza, “You’re really made something of yourself”) Candace Fleming had to wade through loads of inaccurate data produced, in many cases, by Bill himself. To combat this problem, Ms. Fleming employs a regular interstitial segment in the book called “Panning for the Truth” in which she tries to pry some grain of truth out of the bombast. If a person loves making up the story of their own life, how do you ever know what the truth is? Yet in many ways, this is the crux of Bill’s story. He was a storyteller, and to prop himself up he had to, in a sense, prop up the country’s belief in its own mythology. As he was an embodiment of that mythology, he had a vested interest in hyping what he believed made the United States unique. Taking that same message to other countries in the world, he propagated a myth that many still believe in today. Therefore the story of Bill isn’t merely the story of one man, but of a way people think about our country. Bill was merely the vessel. The message has outlived him.

So let’s get back to that earlier question of whether or not you can feature a person with questionable ethics in a biography written for children. It really all just boils down to a question of what the point of children’s biographies is in the first place. Are they meant to inspire, or simply inform, or some kind of combination of both? In the case of unreliable Bill, the self-made man (I’m suddenly hearing Jerry Seinfeld’s voice saying to George Costanza, “You’re really made something of yourself”) Candace Fleming had to wade through loads of inaccurate data produced, in many cases, by Bill himself. To combat this problem, Ms. Fleming employs a regular interstitial segment in the book called “Panning for the Truth” in which she tries to pry some grain of truth out of the bombast. If a person loves making up the story of their own life, how do you ever know what the truth is? Yet in many ways, this is the crux of Bill’s story. He was a storyteller, and to prop himself up he had to, in a sense, prop up the country’s belief in its own mythology. As he was an embodiment of that mythology, he had a vested interest in hyping what he believed made the United States unique. Taking that same message to other countries in the world, he propagated a myth that many still believe in today. Therefore the story of Bill isn’t merely the story of one man, but of a way people think about our country. Bill was merely the vessel. The message has outlived him.

I’ve heard folks online say of the book that they can’t imagine the child who’d come in seeking a bio of Buffalo Bill. Since kids don’t like cowboys like they used to, the very existence of this book in the universe puzzles them. Well, putting aside the fact that enjoying a biography often has very little to do with the fact that you already were interested in the subject (or any nonfiction book, for that matter), let’s just pick apart precisely why a kid might get a lot out of reading about Bill. He was, as I have mentioned, a humbug. But he was also for more than that. He was a fascinating mix of good and evil. He took credit for terrible deeds but also participated in charitable acts (whether out of a sense of obligation or mere money is a question in and of itself). He no longer fits the mold of what we consider a hero to be. He also doesn’t fit the mold of a villain. So what does that leave us with? A very interesting human being and those, truth be told, make for the best biographies for kids.

The fact that Bill is a subject of less than sterling personal qualities is not what makes this book as difficult as it is to write (though it doesn’t help). The real problem with Bill comes right down to his relationships with American Indians. How do we in the 21st century come to terms with Bill’s very white, very 19th century attitudes towards Native Americans? Fleming tackles this head on. First and foremost, she begins the book with “A Note From the Author” where she explains why she would use one term or another to describe the Native Americans in this book, ending with the sentence, “Always my intention when referring to people outside my own cultural heritage is to be respectful and accurate.” Next, she does her research. Primary sources are key, but so is work at the McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming. Her work was then vetted by Dr. Jeffrey Means (Enrolled Member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe), Associate Professor of History at the University of Wyoming in the field of Native American History, amongst others. I was also very taken with the parts of the book that quote Oglala scholar Vine Deloria Jr., explaining at length why Native performers worked for Buffalo Bill and what it meant for their communities.

The fact that Bill is a subject of less than sterling personal qualities is not what makes this book as difficult as it is to write (though it doesn’t help). The real problem with Bill comes right down to his relationships with American Indians. How do we in the 21st century come to terms with Bill’s very white, very 19th century attitudes towards Native Americans? Fleming tackles this head on. First and foremost, she begins the book with “A Note From the Author” where she explains why she would use one term or another to describe the Native Americans in this book, ending with the sentence, “Always my intention when referring to people outside my own cultural heritage is to be respectful and accurate.” Next, she does her research. Primary sources are key, but so is work at the McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming. Her work was then vetted by Dr. Jeffrey Means (Enrolled Member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe), Associate Professor of History at the University of Wyoming in the field of Native American History, amongst others. I was also very taken with the parts of the book that quote Oglala scholar Vine Deloria Jr., explaining at length why Native performers worked for Buffalo Bill and what it meant for their communities.

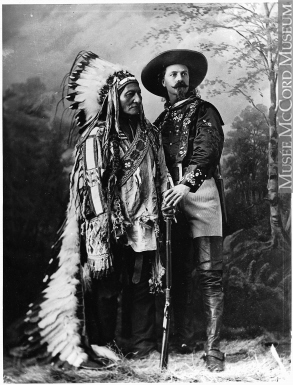

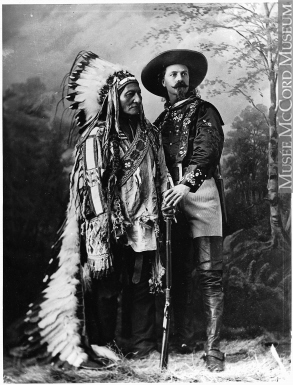

What surprised me the most about the book was that I walked into it with the pretty clear perception that Bill was a “bad man”. A guy who hires American Indians to continually lose or be exploited as part of some traveling show meant to make white Americans feel superior? Yeah. Not on board with that. But as ever, the truth is far more complicated than that. Fleming delves deep not just into the inherently racist underpinnings of Bill’s life, but also its contradictions. Bill hated Custer when he knew the guy and said publicly that the defeat of Custer was no massacre, yet would reenact it as part of his show,  with Custer as the glorified dead hero. He would hire Native performers, pay them a living wage, and speak highly of them, yet at the same time he murdered a young Cheyenne named Yellow Hair and scalped him for his own glory. Fleming is at her best when she recounts the relationship of Bill and Sitting Bull. A photo of the two shows them standing together “as equals . . . but it is obvious that Bill is leading the way while Sitting Bull appears to be giving in. What was the subtext of the photo? That the ‘friendship’ offered in the photograph – and in Wild West performances – honored American Indian dignity only at the expense of surrender to white dominance and control.”

with Custer as the glorified dead hero. He would hire Native performers, pay them a living wage, and speak highly of them, yet at the same time he murdered a young Cheyenne named Yellow Hair and scalped him for his own glory. Fleming is at her best when she recounts the relationship of Bill and Sitting Bull. A photo of the two shows them standing together “as equals . . . but it is obvious that Bill is leading the way while Sitting Bull appears to be giving in. What was the subtext of the photo? That the ‘friendship’ offered in the photograph – and in Wild West performances – honored American Indian dignity only at the expense of surrender to white dominance and control.”

I’m writing this review in the year of 2016 – a year when Donald Trump is running for President of the United States of America. It’s given me a lot of food for thought about American humbuggery. Here in the States, we’ve created a kind of homegrown demagoguery that lauds the successful humbug. P.T. Barnum was a part of that. Huey Long had it down. And Buffalo Bill may have been a different version of these men, but I’d say he belongs to their club. There’s a thin line between “self-made man” and “making stuff up”. Thinner still when the man in question does as much good and as much evil as Buffalo Bill Cody. Fleming walks a tightrope here and I’d say it’s fair to say she doesn’t fall. The sheer difficulty of the subject matter and her aplomb at handling the topic puts her on a higher plane than your average middle grade biography. Will kids seek out Buffalo Bill’s story? I have no idea, but I can guarantee that for those they do they’ll encounter a life and a man that they will never forget.

On shelves September 20th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 3/23/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

poetry,

Roaring Brook,

Best Books,

macmillan,

Julie Morstad,

Neal Porter Books,

Julie Fogliano,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 poetry,

2017 Newbery contenders,

Add a tag

When Green Becomes Tomatoes: Poems for All Seasons

When Green Becomes Tomatoes: Poems for All Seasons

By Julie Fogliano

Illustrated by Julie Morstad

A Neal Porter Book / Roaring Brook Press (Macmillan)

$18.99

ISBN: 9781596438521

Ages 6 and up

On shelves now.

I don’t think I can adequately stress to you the degree to which I did not want to review this book. Not because it isn’t a magnificent title. And not because it isn’t pleasing to both eye and ear alike. No, it probably had more to do with the fact that it’s a work of poetry. I make a point of reviewing poetry regularly, though I’d be the first to say that it wasn’t my first language (if you know what I mean). I respect it but can occasionally find it tough going. I was determined to give this book its due, though. And the only way I could make myself physically sit down and review it was to read it cover to cover again. As I did so I was struck over and over, time and again, by just how melodious the language is here. Look, I’ll level with you. Seasonal poetry books are a dime a dozen. But what Fogliano and Morstad have created together is a lot more than just a book of poems for the changes of the year. This book manages to operate on a level that presents the very act of the seasonal cycle as positively philosophical, yet without distancing itself from its readership. It’s tricky territory, but together Fogliano and Morstad get the job done.

“from a snow-covered tree / one bird singing / each tweet poking / a tiny hole / through the edge of winter”. In the very first poem in When Green Becomes Tomatoes (a poem called “march 20”) the child reader is alerted to a change in the air. The snow is still present and the weather still gloomy, but there is hope on the horizon. Yet rather than turn the book into a paean to warmer weather, poet Julie Fogliano takes time to both celebrate and criticize the passing seasons. By the end of spring you look forward to summer and the end of summer leads to the relief of autumn, and so on and such. Accompanying these thoughts are small poems in lowercase and illustrations carrying the weight and expectations these seasons evoke in us. The end result can only be described in a single word: beautiful.

Like I said, I’ve read a lot of poetry books for kids about the seasons in my day. The good ones have some kind of a hook. Like Joyce Sidman tackling it with colors in Red Sings from Treetops or Jon J. Muth writing the poems entirely as haikus as in Hi, Koo! A Year in Seasons. But Fogliano doesn’t really have a hook, and so I approached the title with trepidation. No hook? You mean it was just going to be . . . poems?! It takes the courage of your convictions to do a poetry book for kids straight these days. And it’s not true that Fogliano didn’t have one ace up her sleeve. A lot of works of poetry start in January (when the year itself technically begins). Using a technique of highlighting random dates, this poet begins the book on March 20th, the first day of spring. A small hook, sure, but at least it’s something.

Like I said, I’ve read a lot of poetry books for kids about the seasons in my day. The good ones have some kind of a hook. Like Joyce Sidman tackling it with colors in Red Sings from Treetops or Jon J. Muth writing the poems entirely as haikus as in Hi, Koo! A Year in Seasons. But Fogliano doesn’t really have a hook, and so I approached the title with trepidation. No hook? You mean it was just going to be . . . poems?! It takes the courage of your convictions to do a poetry book for kids straight these days. And it’s not true that Fogliano didn’t have one ace up her sleeve. A lot of works of poetry start in January (when the year itself technically begins). Using a technique of highlighting random dates, this poet begins the book on March 20th, the first day of spring. A small hook, sure, but at least it’s something.

As for the poems themselves, I was impressed not just with the writing, but with Ms. Fogliano’s grasp of what each season actually entails. There are a LOT of cloudy days, rainy days, and generally blah days in this book. They don’t weigh down the narrative or really make it all that gloomy. You just end up experiencing precisely the same feeling you have when you’re living those days. This is the rare book that acknowledges that spring doesn’t immediately mean sunshine and 55-degree temperatures. There’s a lot of snow and some mud and a whole ton of rain. Listen to how she puts it, though: “today / the sky was too busy sulking to rain / and the sun was exhausted from trying / and everyone / it seemed / had decided / to wear their sadness / on the outside / and even the birds / and all their singing / sounded brokenhearted / inside of all that gray.” It really isn’t until June that things even out, and I respect that. All the seasons are like that. It’s great to watch.

As you might have noted, the poetry found in this book straddles a line between being child-friendly and introspective (the two aren’t mutually exclusive, but neither are they always natural pairs). I found myself noting line after line after line that I wanted to quote. Here’s a small taste for each season.

On Spring: “shivering and huddled close / the forever rushing daffodils / wished they had waited.”

On Summer: “if you ever stopped / to taste a blueberry / you would know / that it’s not really about the blue, at all.”

On Fall: “october please / get back in bed / your hands are cold / your nose is red / october please / go back to bed / your sneezing woke december.”

On Winter: “a gust of wind / blew by my nose / i think i will be frozen soon / this living room / (all cozy chairs and fireplace) / has some real explaining to do.”

Some books of children’s poetry lean heavily on the works of other poets. I won’t presume to name her influences but if the July 12th poem is any indication then William Carlos Williams might have had some influence here. And maybe e.e. cummings too (with all that mudlicious mud).

When she was much younger it’s clear that author Julie Fogliano made some kind of a blood sacrifice to the God of Perfect Illustrator Pairings. How else to explain how she has managed to work alongside such artists as Erin E. Stead and now Julie Morstad? Morstad is no newbie to the field, of course. I’ve been a big fan of her for years, starting with her art for The Swing by Robert Louis Stevenson. Morstad’s great talent lies not necessarily in her waiflike black-eyed children, but rather in how she creates tone. Though there are plenty of sequences in this book of kids playing together or sharing food and soup, for the most part her characters go it alone. These poems are the contemplations of a young person with time and space and nature in spades. I don’t know that if I read Ms. Fogliano’s poetry without the art I would have picked up on that myself. Note too how cyclical the book is. The first poem is the last, sure as shooting, but so too is the person seen at both the beginning and the end. It’s the same kid wearing the same clothes, which makes a subtle implication that though a whole year has gone by, time is simply doubling back on itself. Not sure what to make of that one, frankly.

When she was much younger it’s clear that author Julie Fogliano made some kind of a blood sacrifice to the God of Perfect Illustrator Pairings. How else to explain how she has managed to work alongside such artists as Erin E. Stead and now Julie Morstad? Morstad is no newbie to the field, of course. I’ve been a big fan of her for years, starting with her art for The Swing by Robert Louis Stevenson. Morstad’s great talent lies not necessarily in her waiflike black-eyed children, but rather in how she creates tone. Though there are plenty of sequences in this book of kids playing together or sharing food and soup, for the most part her characters go it alone. These poems are the contemplations of a young person with time and space and nature in spades. I don’t know that if I read Ms. Fogliano’s poetry without the art I would have picked up on that myself. Note too how cyclical the book is. The first poem is the last, sure as shooting, but so too is the person seen at both the beginning and the end. It’s the same kid wearing the same clothes, which makes a subtle implication that though a whole year has gone by, time is simply doubling back on itself. Not sure what to make of that one, frankly.

With poetry, we have to play the game of answering what ages we think the poems are appropriate for. This book poses a bit of a challenge on that front. Some are younger, some definitely older. This mix will allow kids of all ages to take part in the fun, even as the book asks questions like whether or not there is a space between where things begin and things end “or just a slow and gentle fading”. Enticing to the eye but, more importantly almost, alluring to the brain as kids parse what Fogliano is trying to say, this is a book that has the potential (with the right teacher or parent) to convert the formerly unconvertible to the wonders of poetry itself. The truth of the matter is this: Fogliano and Morstad will make poets of us all.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews:

Other Reviews:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 1/24/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

macmillan,

Lisa Brown,

Neal Porter Books,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 picture books,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

Reviews,

Roaring Brook,

Best Books,

picture book reviews,

Add a tag

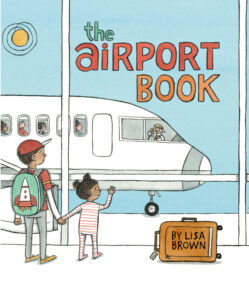

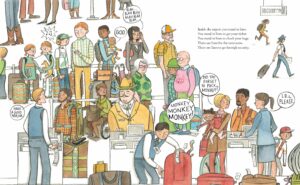

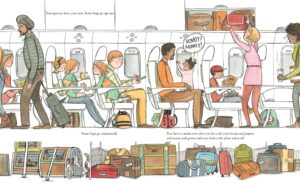

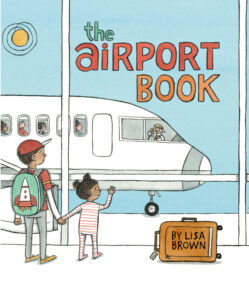

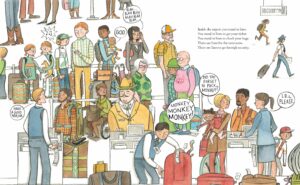

The Airport Book

The Airport Book

By Lisa Brown

A Neal Porter Book, Roaring Brook, an imprint of Macmillan

$16.99

ISBN: 978-1-62672-091-6

Ages 4-7

On shelves May 10th.

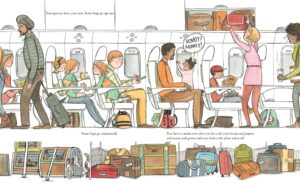

Look, I don’t wanna brag but I’m what you might call a going-to-the-airport picture book connoisseur. I’ve seen them all. From out-of-date fare like Byron Barton’s Airport to the uniquely clever Flight 1-2-3 by Maria Van Lieshout to the odd but helpful Everything Goes: In the Air by Brian Biggs. Heck, I’ve even examined at length books about the vehicles that drive on the airport tarmac (see: Brian Floca’s Five Trucks). If it helps to give kids a better sense of what flying is like, I’ve seen it, baby. And I will tell you right here and now that not a single one of these books is quite as good at explaining every step of the journey as well as Lisa Brown’s brand new The Airport Book. I’d even go so far as to say that it’s more than just an instructional how-to. Packed with tiny details that make each rereading worthwhile, a plot that sweeps you along, and downright great information, this one here’s a keeper to its core.

“When you go to the airport, you can take a car, a van, a bus, or even a train. Sometimes we take a taxicab.” A family of four prepares for a big trip. Bags are packed with the haste that anyone with small children will recognize. Speed is of the essence. As they arrive at the airport we meet other people and families taking the same flight. There’s airport security to get through (the book mentions the many lines you sometimes have to stand in to get where you’re going), the awesome size of the airport itself, the gate, and then the plane. As we watch the younger sister in the family is having various mild freakouts over her missing (or is it?) stuffed monkey. The monkey in question is always in our view, packed in a suitcase, discovered by a dog during the flight, and finally reuniting with its owner on the luggage carousel. The family meets up with the grandparents and at last the vacation can begin. That is, until they all have to go home again.

The problem with most airport-related picture books is something I like to call the Fly Away Home conundrum. Originally penned by Eve Bunting, Fly Away Home is one of those rare picture books out there that deal with homelessness in a realistic way. The story features a father and son living out of an airport. Since it touches on such an important, and too little covered, topic, the book continues to appear on required reading lists, in spite of the fact that the very premise is now woefully out-of-date. There are few areas of everyday American life that have changed quite so dramatically over such a short amount of time as the average airport experience. That’s why so many things about The Airport Book rang true for me. When Brown covers the facts surrounding departures and goodbyes to family and friends, she doesn’t set the scene inside the building but rather on the sidewalk outside of ticketing, as people are dropped off. Later you see people at their gate plugging in their cell phones willy-nilly (something I’ve never seen in a picture book before). It lends the book a kind of air of authenticity.

The problem with most airport-related picture books is something I like to call the Fly Away Home conundrum. Originally penned by Eve Bunting, Fly Away Home is one of those rare picture books out there that deal with homelessness in a realistic way. The story features a father and son living out of an airport. Since it touches on such an important, and too little covered, topic, the book continues to appear on required reading lists, in spite of the fact that the very premise is now woefully out-of-date. There are few areas of everyday American life that have changed quite so dramatically over such a short amount of time as the average airport experience. That’s why so many things about The Airport Book rang true for me. When Brown covers the facts surrounding departures and goodbyes to family and friends, she doesn’t set the scene inside the building but rather on the sidewalk outside of ticketing, as people are dropped off. Later you see people at their gate plugging in their cell phones willy-nilly (something I’ve never seen in a picture book before). It lends the book a kind of air of authenticity.

The story’s good and the art’s great but what I liked about the book was the language. Brown never tells you precisely what is going to happen, but she does mention the likelihoods. “Sometimes the plane is bouncy, but most of the time it is smooth.” “Sometimes the sidewalks and staircases move by themselves.” “Sometimes there are small beeping cars driving through . . .” As you read, you realize that in a way the narration of the book is being created for us from the perspective of the big brother. He’ll occasionally insert little notes that are probably of more use to him than us. Example: “You have to hold your little sister’s hands tight, or she could get lost.” Mind you, some of the sections have the ring of poetry to them, while staying squarely within a believable child’s voice. I was particularly fond the of the section that says, “Outside there are clouds and clouds and clouds.”

With all the calls for more diverse picture books to be published, it would be noticeable if Ms. Brown’s book didn’t have a variety of families, races, ages, genders, etc. What’s notable to me is that she isn’t just checking boxes here. Her diversity far surpasses those books where they’ll throw in the occasional non-white character in a group shot. Instead, the main family has a dark-skinned father and light-skinned, blond mother. Travels through the airport show adults in wheelchairs, twins, women in headscarves, Sikhs, pregnant ladies, and more. In other words, what you’d actually see in an airport these days.

With all the calls for more diverse picture books to be published, it would be noticeable if Ms. Brown’s book didn’t have a variety of families, races, ages, genders, etc. What’s notable to me is that she isn’t just checking boxes here. Her diversity far surpasses those books where they’ll throw in the occasional non-white character in a group shot. Instead, the main family has a dark-skinned father and light-skinned, blond mother. Travels through the airport show adults in wheelchairs, twins, women in headscarves, Sikhs, pregnant ladies, and more. In other words, what you’d actually see in an airport these days.

And then the little details come up. Brown throws into the book a surprising array of tiny look-and-discover elements, suggesting that perhaps this book would be just as much fun in its way as a Where’s Waldo? game for older siblings as it is their younger brethren. Ask them if they can find The Wright Brothers, Hatchet (don’t think too hard about what happens to the plane in that book), the mom’s copy of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, or the person looking for Amelia Earhart (who may not be as difficult to find as you think). There’s also a cast of characters that command your attention like the businesswoman who’s always on her cell phone and the short artist with the mysteriously shaped package.

There’s nothing to say that in five years airports will be just as different to us today as pre-9/11 airports are now. Yet even if our airports start requiring us to hula hoop and dance the Hurly Burly, Brown’s book is still going to end up being the go-to text desperate parents turn to when they need a book that explains to their children what an average airplane flight looks like. It pretty much gets everything right, exceeding expectations. Generally speaking, books that tell kids about what something is like (be it a trip to the dentist or a new babysitter) are pedantic, didactic, dull as dishwater fare. Brown’s book, in contrast, has flare. Has pep. Has a beat and you can dance to it. Like I said, this may be the best dang going-to-the-airport book I can name (though you should certainly check out the others I’m mentioned at the beginning of this review). A treat, it really is. A treat.

On shelves May 10th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Interviews: Miss Marple’s Musings

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 11/30/2013

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Best Books of 2013,

Reviews,

picture books,

Roaring Brook,

Gus Gordon,

macmillan,

Australian children's books,

Neal Porter Books,

Australian imports,

Reviews 2013,

2013 picture books,

2013 reviews,

New York picture books,

picture boo,

Best Books,

Add a tag

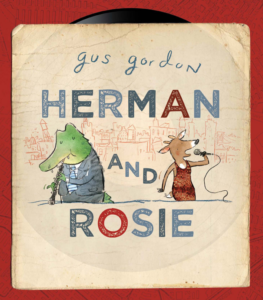

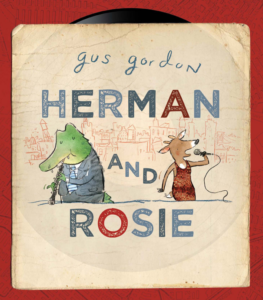

Herman and Rosie

Herman and Rosie

By Gus Gordan

Roaring Brook (an imprint of Macmillan)

$17.99

ISBN: 978-1596438569

Ages 3-7

On shelves now

New Yorkers are singularly single minded. It’s not enough that our city be rich, popular, and famous. We apparently are so neurotic that we need to see it EVERYWHERE. In movies, on television, and, of course, in books. Children’s books, however, get a bit of a pass in this regard. It doesn’t matter where you grow up, most kids get a bit of a thrill when they see their home city mentioned in a work of literature. Here in NYC, teachers go out of their way to find books about the city to read and study with their students. As a result of this, in my capacity as a children’s librarian I make a habit of keeping an eye peeled for any and all New York City related books for the kiddos. And as luck would have it, in the year 2013 I saw a plethora of Manhattan-based titles. Some were great. Some were jaw-droppingly awful. But one stood apart from the pack. Written by an Aussie, Herman and Rosie, author Gus Gordon has created the first picture book I’ve ever seen to successfully put its finger on the simultaneous beauty and soul-gutting loneliness of big city life. The fact that it just happens to be a fun story about an oboe-tooting croc and deer chanteuse is just icing on the cake.

Herman and Rosie are city creatures through and through. Herman is a croc with a penchant for hotdogs and yogurt and playing his oboe out the window of his 7th story home. In a nearby building, Rosie the deer likes pancakes and jazz records and singing in nightclubs, even if no one’s there to hear her. Neither one knows the other, so they continue their lonely little lives unaware of the potential soulmate nearby. One day Rosie catches a bit of Herman’s music and not long thereafter Herman manages to hear a snatch of a song sung by Rosie. They like what they hear but through a series of unfortunate events they never quite meet up. Then Herman gets fired from his job in sales and Rosie’s favorite jazz club goes belly up. Things look bad for our heroes, until a certain cheery day where it all turns around for them.

You can know a city from afar but never quite replicate it in art. I do not know how many times Gus Gordon has visited NYC. I don’t know his background here or how often he’s visited over the course of his lifetime. All I know is he got Manhattan DOWN, man! Everything from the water towers and the rooftop landscapes to the very color of the subway lines is replicated in his pitch perfect illustrations. Maybe the medium has a lot to answer for. I love the map endpapers that identify not just where Herman and Rosie live, but also where you can find a great hot dog place. I like how the art is a mix of real postcards showcasing everything from Central Park (look at the Essex House!!) to the Rose Reading Room in the main branch of New York Public Library.

You can know a city from afar but never quite replicate it in art. I do not know how many times Gus Gordon has visited NYC. I don’t know his background here or how often he’s visited over the course of his lifetime. All I know is he got Manhattan DOWN, man! Everything from the water towers and the rooftop landscapes to the very color of the subway lines is replicated in his pitch perfect illustrations. Maybe the medium has a lot to answer for. I love the map endpapers that identify not just where Herman and Rosie live, but also where you can find a great hot dog place. I like how the art is a mix of real postcards showcasing everything from Central Park (look at the Essex House!!) to the Rose Reading Room in the main branch of New York Public Library.

But the art is far more than simply a clever encapsulation of a location. It took several readings before I could see a lot of what Gordon was up to. Here’s an example: Take a look at the two-page spread where Herman is leaving his office for the last time with all his goods in a box, while on the opposite page Rosie trudges home from the closing club, her high heeled red shoes sitting forlornly in the basket of her bike. The two images take place at different times of the day, but if you look closely you’ll see that they’re the same street corner. Yet where Herman’s New York is filled with loud angry voices and sounds, Rosie’s is near silent, a black wash representing the oncoming night. Note too that while Herman’s mailbox was a mixed media photo, Rosie’s is painted in a black wash with some crayon scribbles. It’s a subtle difference, but I love how it sort of represents how objects become less real when the lights begin to dim. And the book is just FILLED with tiny, clever details. From the pictures and instructions that grace Herman’s cubicle at work to the fact that Rosie clearly washes her clothes at home (the clothesline the runs from her bike to the old-fashioned vacuum tube television was my first clue) to Herman’s bed in the living room, Gordon is constantly peppering his book with elements that give little insights into who these two characters really are.

And that right there is the the crux of the book. Time and time again Gordon returns to this idea of how lonely it can be to live in a busy place. The idea that you can be surrounded by hundreds of thousands of people and feel as alone as if you were on a desert island is a tricky concept to convey to small fry. Herman’s whole personality, in a way, hinges on the fact that he’s terrible at his job as a telecaller because all he wants to do is talk to people on the phone, not sell them things. He longs for connection. Rosie, meanwhile, finds a certain level of connection through her singing gig. Once that gig leaves, her feelings of extreme loneliness echo Herman’s with the loss of his job. Their sole lifelines to the outside world have been severed against their wills. If this were a book for adults we’d undoubtedly also get a couple scenes of the various failed dates they fine themselves on (well, Rosie certainly… I’m not so sure that Herman’s the serial dater type). Kids understand loneliness. They get that. They’ll get this.

The book also plays on the natural inclination for a happy resolution, and the near misses when Herman almost meets Rosie and Rosie just barely misses Herman can be excruciating. You are fairly certain the two are made for one another (the natural tendencies of crocs to eat deer notwithstanding) so it can be particularly painful to see so many almost wases. This feeling is, admittedly, partly diluted by the fact that you’re not quite sure what will happen when the two DO meet. Are they going to fall in love? Well, not exactly. There may be a kind of child reader that hopes for that ending, but instead we’re given a conclusion where the two just learn to make beautiful music together, and in the course of that music happen to find financial success as well. This is New York, after all. Love’s great but a steady paycheck’s even better.

The book also plays on the natural inclination for a happy resolution, and the near misses when Herman almost meets Rosie and Rosie just barely misses Herman can be excruciating. You are fairly certain the two are made for one another (the natural tendencies of crocs to eat deer notwithstanding) so it can be particularly painful to see so many almost wases. This feeling is, admittedly, partly diluted by the fact that you’re not quite sure what will happen when the two DO meet. Are they going to fall in love? Well, not exactly. There may be a kind of child reader that hopes for that ending, but instead we’re given a conclusion where the two just learn to make beautiful music together, and in the course of that music happen to find financial success as well. This is New York, after all. Love’s great but a steady paycheck’s even better.

The truth of the matter is that Herman and Rosie could be set in L.A. or Minneapolis or Atlanta or even Sydney and I’d still love it as much as I do with its New York flavor, tone, and beat. It wouldn’t be exactly the same, but it’s the bones of the book that are strong. The setting is just a bonus, really. With original mixed media, a text that’s subtle and succinct, and a story that rings both true and original (for a picture book medium anyway), this is a city book, a true city book, to its core. Author Markus Zusak said the book was “Quirky, soulful and alive”. Can’t put it any better than that. What he said.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews:

Misc: If you want to see some alternate covers for this book, scroll to the bottom of this fun blog post.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 3/13/2012

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

concept books,

Roaring Brook,

macmillan,

Laura Vaccaro Seeger,

2012 picture books,

Neal Porter Books,

2012 reviews,

Best Books of 2012,

2013 Caldecott contender,

color concepts,

Uncategorized,

Add a tag

Green

Green

By Laura Vaccaro Seeger

A Neal Porter Book – Roaring Brook (an imprint of Macmillan)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-1-59643-397-7

Ages 4-8

On shelves March 27th

Sometimes you just want to show a kid a beautiful picture book. Sometimes you also want that book to be recent. That’s the tricky part. Not that there aren’t pretty little picture books churned out of publishing houses every day. Of course there are. But when you want something that distinguishes itself and draws attention without sparkles or glitter the search can be a little fraught. We children’s librarians sit and wait for true beauty to fall into our laps. The last time I saw it happen was Jerry Pinkney’s The Lion and the Mouse. Now I’m seeing it again with Laura Vaccaro Seeger’s Green. I mean just look at that cover. I vacillate between wanting to smear those thick paints with my hands and wanting to lick it to see if it tastes like green frosting. If my weirdness is any kind of a litmus test, kids will definitely get a visceral reaction when they flip through the pages. I know we’re talking colors here but if I were to capture this book in a single word then there’s only one that would do: Delicious.

Open the book and the first pictures you see are of a woodland scene. Two leaves hang off a nearby tree as the text reads “forest green”. Turn the page and those leaves, cut into the paper itself, flip over to two fishies swimming in the deep blue sea. A tortoise swims lazily by, bubbles rising from its head (“sea green”). Another page and the holes of the bubbles are turned over to become the raised bumps on a lime. And so it goes with each new hole or cut connecting one kind of green to another. We see khaki greens, wacky greens, slow greens and glow greens until at last Seeger fills the page with boxes filled with different kinds of green. This is followed by a stop sign and the words “never green” against an autumn background. On the next page it is winter and “no green” followed by an image of a boy planting something. The final spread shows a man and his daughter gazing at a tree. The description: “forever green”. You bet.

Can a color be political? Absolutely. In a given election season you’ll see red vs. blue, after all. In children’s books colors would historically be associated with races or countries (hence the flare up around titles like Two Reds). Green occupies a hazy middle ground here. We all know about the Green Party or green activism. However, it’s not as if you’ll find many parents forbidding their children to read this book because it pushes a pro-environment agenda. Seeger is subtler than that. Yes, her book does end with humans planting and admiring trees, but thanks to her literary restraint the message isn’t thwapping you over the head with a tire iron. She could have turned her “no green” two-page spread into some barren landfill-esque wasteland. Instead we see a snow scene. This is followed by the only silent two pages i

Can a color be political? Absolutely. In a given election season you’ll see red vs. blue, after all. In children’s books colors would historically be associated with races or countries (hence the flare up around titles like Two Reds). Green occupies a hazy middle ground here. We all know about the Green Party or green activism. However, it’s not as if you’ll find many parents forbidding their children to read this book because it pushes a pro-environment agenda. Seeger is subtler than that. Yes, her book does end with humans planting and admiring trees, but thanks to her literary restraint the message isn’t thwapping you over the head with a tire iron. She could have turned her “no green” two-page spread into some barren landfill-esque wasteland. Instead we see a snow scene. This is followed by the only silent two pages i

Bandits

Bandits

By Johanna Wright

A Neal Porter Book – Roaring Brook (an imprint of Macmillan)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-1-59643-583-4

Ages 4-8

On shelves now

There has been inadequate use of raccoons in children’s literature. Seems to me that if you have a furry woodland creature with a homegrown mask as part of its fuzzy face, it’s a crime NOT to make it a creeping bandit at some point. I mean, raccoons basically live up to their sneaky looks anyway. They turn over folks’ garbage cans. They lark about when the world is dark. Over the years I’ve seen the occasional book here and there give these creatures of the night their due, but few have done it quite as beautifully as Johanna Wright’s Bandits. Having discovered Ms. Wright when she wrote the utterly odd and charming The Secret Circus, Bandits proves to be an evocative follow-up. As amusing as it is to read (and it is amusing) Wright’s original eclectic style also makes this one of the stranger and yet more beautiful recent picture books out there. A funny mix of unreliable narration and sweet family life, these bandits are the ones you’ll think of from here on in whenever you spot a raccoon’s telltale face.

“When the sun goes down and the moon comes up, beware of the bandits that prowl through the night.” Traveling en masse, a family of raccoons begins its evening of mini larceny. Raiding garbage cans and stripping the apples from the topmost branches of trees these sneaky petes are clearly under the impression that they are villains par excellence. Even when their ramblings are discovered by (highly amused) humans they believe that they’re in possession of some pretty choice “loot”. And when the sun comes up, the family goes inside to sleep and read some books. “But just until the sun goes down.”

Part of what makes the book so charming is that while the raccoons appear to be entirely of the opinion that they are master thieves stealing great treasures from their unsuspecting victims, in truth their capers are fairly innocent and their “treasures” items that folks don’t need (like the garbage) or don’t mind losing (like the fruit from the trees). I mean, when you get down to it, the sneakiest things these “bandits” do, aside from knocking over the odd garbage can, is to brush their teeth in somebody’s fountain. Booga booga! I love that the writing in this book is clearly from their perspective too. Even as the pictures make it clear that you’re dealing with some pretty tame criminals, they’re trying to impress you with their daring. At one point you read, “They baffle the fuzz with each little trick” while the picture shows the raccoons tiptoeing past an old hound dog that couldn’t be less interested. And multiple readings of this book yield multiple ways to grow fond of the raccoon family unit. After all, there are some scenes of them relaxing in their home, their thoughts far from their pilfering ways. Reread the bo

Part of what makes the book so charming is that while the raccoons appear to be entirely of the opinion that they are master thieves stealing great treasures from their unsuspecting victims, in truth their capers are fairly innocent and their “treasures” items that folks don’t need (like the garbage) or don’t mind losing (like the fruit from the trees). I mean, when you get down to it, the sneakiest things these “bandits” do, aside from knocking over the odd garbage can, is to brush their teeth in somebody’s fountain. Booga booga! I love that the writing in this book is clearly from their perspective too. Even as the pictures make it clear that you’re dealing with some pretty tame criminals, they’re trying to impress you with their daring. At one point you read, “They baffle the fuzz with each little trick” while the picture shows the raccoons tiptoeing past an old hound dog that couldn’t be less interested. And multiple readings of this book yield multiple ways to grow fond of the raccoon family unit. After all, there are some scenes of them relaxing in their home, their thoughts far from their pilfering ways. Reread the bo

Presenting Buffalo Bill: The Man Who Invented the Wild West

Presenting Buffalo Bill: The Man Who Invented the Wild West So let’s get back to that earlier question of whether or not you can feature a person with questionable ethics in a biography written for children. It really all just boils down to a question of what the point of children’s biographies is in the first place. Are they meant to inspire, or simply inform, or some kind of combination of both? In the case of unreliable Bill, the self-made man (I’m suddenly hearing Jerry Seinfeld’s voice saying to George Costanza, “You’re really made something of yourself”) Candace Fleming had to wade through loads of inaccurate data produced, in many cases, by Bill himself. To combat this problem, Ms. Fleming employs a regular interstitial segment in the book called “Panning for the Truth” in which she tries to pry some grain of truth out of the bombast. If a person loves making up the story of their own life, how do you ever know what the truth is? Yet in many ways, this is the crux of Bill’s story. He was a storyteller, and to prop himself up he had to, in a sense, prop up the country’s belief in its own mythology. As he was an embodiment of that mythology, he had a vested interest in hyping what he believed made the United States unique. Taking that same message to other countries in the world, he propagated a myth that many still believe in today. Therefore the story of Bill isn’t merely the story of one man, but of a way people think about our country. Bill was merely the vessel. The message has outlived him.

So let’s get back to that earlier question of whether or not you can feature a person with questionable ethics in a biography written for children. It really all just boils down to a question of what the point of children’s biographies is in the first place. Are they meant to inspire, or simply inform, or some kind of combination of both? In the case of unreliable Bill, the self-made man (I’m suddenly hearing Jerry Seinfeld’s voice saying to George Costanza, “You’re really made something of yourself”) Candace Fleming had to wade through loads of inaccurate data produced, in many cases, by Bill himself. To combat this problem, Ms. Fleming employs a regular interstitial segment in the book called “Panning for the Truth” in which she tries to pry some grain of truth out of the bombast. If a person loves making up the story of their own life, how do you ever know what the truth is? Yet in many ways, this is the crux of Bill’s story. He was a storyteller, and to prop himself up he had to, in a sense, prop up the country’s belief in its own mythology. As he was an embodiment of that mythology, he had a vested interest in hyping what he believed made the United States unique. Taking that same message to other countries in the world, he propagated a myth that many still believe in today. Therefore the story of Bill isn’t merely the story of one man, but of a way people think about our country. Bill was merely the vessel. The message has outlived him. The fact that Bill is a subject of less than sterling personal qualities is not what makes this book as difficult as it is to write (though it doesn’t help). The real problem with Bill comes right down to his relationships with American Indians. How do we in the 21st century come to terms with Bill’s very white, very 19th century attitudes towards Native Americans? Fleming tackles this head on. First and foremost, she begins the book with “A Note From the Author” where she explains why she would use one term or another to describe the Native Americans in this book, ending with the sentence, “Always my intention when referring to people outside my own cultural heritage is to be respectful and accurate.” Next, she does her research. Primary sources are key, but so is work at the McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming. Her work was then vetted by Dr. Jeffrey Means (Enrolled Member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe), Associate Professor of History at the University of Wyoming in the field of Native American History, amongst others. I was also very taken with the parts of the book that quote Oglala scholar Vine Deloria Jr., explaining at length why Native performers worked for Buffalo Bill and what it meant for their communities.

The fact that Bill is a subject of less than sterling personal qualities is not what makes this book as difficult as it is to write (though it doesn’t help). The real problem with Bill comes right down to his relationships with American Indians. How do we in the 21st century come to terms with Bill’s very white, very 19th century attitudes towards Native Americans? Fleming tackles this head on. First and foremost, she begins the book with “A Note From the Author” where she explains why she would use one term or another to describe the Native Americans in this book, ending with the sentence, “Always my intention when referring to people outside my own cultural heritage is to be respectful and accurate.” Next, she does her research. Primary sources are key, but so is work at the McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming. Her work was then vetted by Dr. Jeffrey Means (Enrolled Member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe), Associate Professor of History at the University of Wyoming in the field of Native American History, amongst others. I was also very taken with the parts of the book that quote Oglala scholar Vine Deloria Jr., explaining at length why Native performers worked for Buffalo Bill and what it meant for their communities. with Custer as the glorified dead hero. He would hire Native performers, pay them a living wage, and speak highly of them, yet at the same time he murdered a young Cheyenne named Yellow Hair and scalped him for his own glory. Fleming is at her best when she recounts the relationship of Bill and Sitting Bull. A photo of the two shows them standing together “as equals . . . but it is obvious that Bill is leading the way while Sitting Bull appears to be giving in. What was the subtext of the photo? That the ‘friendship’ offered in the photograph – and in Wild West performances – honored American Indian dignity only at the expense of surrender to white dominance and control.”

with Custer as the glorified dead hero. He would hire Native performers, pay them a living wage, and speak highly of them, yet at the same time he murdered a young Cheyenne named Yellow Hair and scalped him for his own glory. Fleming is at her best when she recounts the relationship of Bill and Sitting Bull. A photo of the two shows them standing together “as equals . . . but it is obvious that Bill is leading the way while Sitting Bull appears to be giving in. What was the subtext of the photo? That the ‘friendship’ offered in the photograph – and in Wild West performances – honored American Indian dignity only at the expense of surrender to white dominance and control.”

Good morning, Betsy!

Based on your review, I’m going to look for this one! I knew it was on the horizon but felt that I didn’t have the time or energy for it. BUT. She quotes Deloria? That’s astonishing. I don’t recall that having been done before (course it is not yet 5 AM and I’ve not had enough coffee, so there’s that!). For those who don’t know Deloria, he’s a towering figure in American Indian Studies and amongst Native communities. Get his book, CUSTER DIED FOR YOUR SINS. And then get all his other books. And then get books by his son, Philip. In the meantime, pull up Floyd Crow Westerman’s song, CUSTER DIED FOR YOUR SINS, on whatever music service you use. And then listen to all his other songs, too.

Debbie

Hi Debbie!

Definitely 100% you need to read this book. And I’m so glad you mentioned the Deloria quote. He’s not the only scholar she quotes, but I found his comments in the book particularly insightful so I had to include him in the mentions. Very interested to hear what you think about the book.