Here at Oxford, we love words. We love when they have ancient histories, we love when they have double-meanings, we love when they appear in alphabet soup, and we love when they are made up.

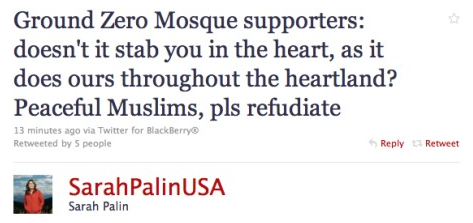

Last week on The Sean Hannity Show, Sarah Palin pushed for the Barack and Michelle Obama to refudiate the NAACP’s claim that the Tea Party movement harbors “racist elements.” (You can still watch the clip on Mediaite and further commentary at CNN.) Refudiate is not a recognized word in the English language, but a curious mix of repudiate and refute. But rather than shrug off the verbal faux pas and take more care in the future, Palin used it again in a tweet this past Sunday.

Note: This tweet has been since deleted and replaced by this one.

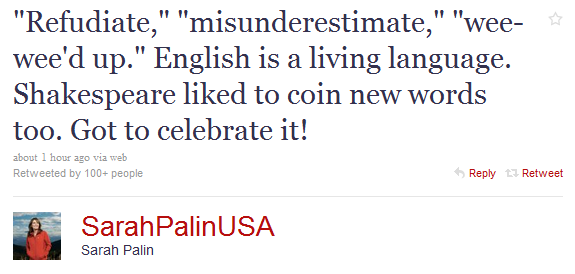

Later in the day, Palin responded to the backlash from bloggers and fellow Twitter users with this:

Whether Palin’s word blend was a subconscious stroke of genius, or just a slip of the tongue, it seems to have made a critic out of everyone. (See: #ShakesPalin) Lexicographers sure aren’t staying silent. Peter Sokolowksi of Merriam-Webster wonders, “What shall we call this? The Palin-drome?” And OUP lexicographer Christine Lindberg comments thus:

The err-sat political illuminary Sarah Palin is a notional treasure. And so adornable, too. I wish you liberals would wake up and smell the mooseburgers. Refudiate this, word snobs! Not only do I understand Ms. Palin’s message to our great land, I overstand it. Let us not be countermindful of the paths of freedom stricken by our Founding Fathers, lest we forget the midnight ride of Sam Revere through the streets of Philadelphia, shouting “The British our coming!” Thank the God above that a true patriot voice lives on today in Sarah Palin, who endares to live by the immorternal words of Nathan Henry, “I regret that I have but one language to mangle for my country.”

Mark Liberman over at Language Log asks, “If she really thought that refudiate was Shakespearean, wouldn’t she have left the original tweet proudly in place?”

He also points out that Palin did not coin the refudiate word blend. In fact, he says, “A

Elvin Lim is Assistant Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com. See Lim’s previous OUPblogs here.

Americans celebrate Independence Day on July 4, the day the words of the Declaration of Independence were set on parchment. John Adams had famously predicted that this day “ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.” Because these celebrations have become annual rituals, we have stopped thinking about exactly what it is we are celebrating.

For a glaring fact stares at us in the face. The Declaration of Independence has absolutely no legal or constitutional status. Presidents and journalists alike appropriate the principles it articulated in their rhetorical flourishes, but for all its symbolic power, the Declaration cannot be quoted by a judge on the Supreme Court to justify an opinion.

A National Day ought to commemorate what it is to be American, and the truth is, the Declaration may well have been the necessary, though certainly not the sufficient part of what made America America. In 1776, the Continental Congress severed our ties to the British crown. That was only a negative act which did not positively define who we were. That positive definition would only come in 1789, when “We the People” would constitute the American nation.

Two hundred years after the fact, Americans commemorate the events of the 1770s and the 1780s as if they were the same decade. But (in order to understand the strive in our contemporary politics) it is important to recall that the 1770s (and the Declaration) and the 1780s (and the Constitution) represented two opposite world-views. The revolutionary generation and the Founding generation were not always on the same page.

The Declaration, ultimately, was an act to guarantee our negative liberties. (Independence = freedom from.) It was a revolutionary act by “one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another.” The revolutionary generation thought, contrary to what most modern liberals believe, that government was evil. The less of it we had to endure, the better.

The Constitution, in contrast, was an act to guarantee our positive liberties or our freedom to do certain things. The American People came together “in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.” The Founding generation, chastened by the inadequacies of the Continental Congress, came to see government in more benign terms. Contrary to Glenn Beck, 1789 was the culmination of a collective call for more government, not less. By 1789, memories of government as a source of evil had receded into the background, while promises of government as a force to do good hovered in the foreground.

The Declaration and Constitution are not of a piece, but are in fact the book-ends of the American ideological spectrum, presenting two competing visions of government; whether it is the so