new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Sean Qualls, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 24 of 24

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Sean Qualls in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Sean Qualls,

on 5/13/2016

Blog:

News from Sean Qualls

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

mythology,

brooklyn,

african american,

race,

identity,

children's book illustrator,

park slope,

sean qualls,

street fair,

black americans,

mad arts,

south slope,

artist,

illustrator,

ny,

history,

Add a tag

** Alex Haley's Roots,

as a kid, got me interested in my own family's ancestry. Although, it wasn't until about 10 years ago, around the time my son was born, that I finally started digging on my mother's side of the family tree. If you've ever done any digging yourself you know how exciting and time consuming it can be, but in a short amount of time I made decent progress.

Then a couple of years ago, my aunt gave me these two portraits of my great-grandparents.I'm guessing the photos are about 100 years old.

Their daughter, my grandmother, Blanche, was born in either 1916 or 1917 so I estimate the photos were taken around then, give or take a few years. These portraits are a part of my family history. And until seeing them and delving into my family's ancestry online, it was a family history that I was not too sure actually existed let alone connected to a larger American history.

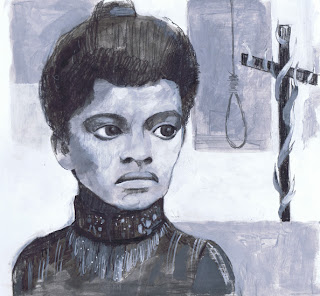

Part of what fuels my art (and illustration) is the desire to shine a light on those who have been forgotten by history, underrepresented or misrepresented. My goal is not to merely tell their stories but to reframe them and their lives. By reframing, I mean looking at people and events from a different vantage point and thereby changing the way we perceive them, reminding us that identity is perception and therefore malleable, not static. The first piece of work where I consciously used reframing was A Brief History of Sambo.

For me, the portraits of my great-grandparents suggest that they were people that mattered, even though their names may only be a small piece of a larger historical record. Often times African-American history is linked to the history of oppression, poverty, brutality and blight, as though they are all synonymous. In terms of success, names like CJ Walker, George Washington Carver and Frederick Douglas are important and familiar but by no means the whole story. There are countless people who we learn about during the 28 days of February, many who were part of the Civil-Rights Movement but still that's just a portion of the picture. Industries such as law, medicine, art, invention, publishing, hospitality, real estate and apparel are all areas where numerous African-Americans made a name for themselves. People like Arthur Gaston, Jeremiah G. Hamilton, John Coburn and Chloe Spear are just a few names but their success defies the perceived norm and that success was not confined

to just one era but was a truth, for some, throughout the history of Blacks in America. Given the circumstances of how we arrived here, our presence in America today conveys a success that pervades all of American history.

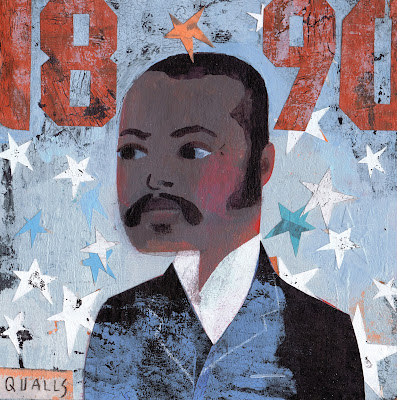

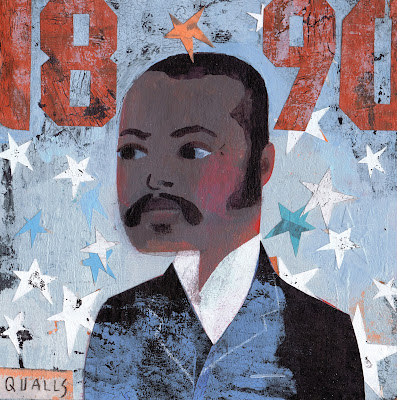

Back to this week's piece. In the spirit of those industrious people who's stories remain untold (and the portraits of my great-grandparents), I created this week's piece-"Black Business 1890."

The portrait is of no one in particular and the date arbitrary but the objective of the piece is to emphasize my previous points. The print is 10x10" including 2" borders on all sides. Printed on heavyweight, ph-neutral, cold-press watercolor paper with archival inks. Just respond here or email me [email protected] with Weekly Painting #9 in the subject if you would like one.

I apologize to anyone who has been waiting for these updates. It's been awhile, I know. I have more to share so stay tuned!

Oh,one more thing.  This Sunday, May 15th in Brooklyn,

This Sunday, May 15th in Brooklyn,

I will be at the 5th Ave Street Fair, 5th Ave between 1st and 2nd Street in the artist area. I may have one or two proofs left of the Black Business 1890 and a Brief History of Sambo. Hope to see you!

Sean

============================================================

Copyright © Sean Qualls 2016, All rights reserved.

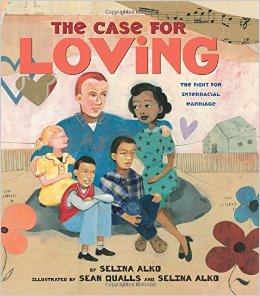

Earlier this year, The Case for Loving: The Fight for Interracial Marriage, by Selina Alko, illustrated by Alko and Sean Qualls, was published by Arthur A. Levine Books. It got starred reviews from Kirkus and Publisher's Weekly. The reviewer at Horn Book gave it a (2), which means the review was printed in The Horn Book Magazine.

The review from The New York Times and my review, were mixed, and as I'll describe later, may be the reasons revisions were made to the second printing of the book.

Let's start with the synopsis for The Case for Loving:

For most children these days it would come as a great shock to know that before 1967, they could not marry a person of a race different from their own. That was the year that the Supreme Court issued its decision in Loving v. Virginia.

This is the story of one brave family: Mildred Loving, Richard Perry Loving, and their three children. It is the story of how Mildred and Richard fell in love, and got married in Washington, D.C. But when they moved back to their hometown in Virginia, they were arrested (in dramatic fashion) for violating that state's laws against interracial marriage. The Lovings refused to allow their children to get the message that their parents' love was wrong and so they fought the unfair law, taking their case all the way to the Supreme Court - and won!

On Feb 6, 2015,

The New York Times reviewer, Katheryn Russell-Brown, wrote:

Alko’s calm, fluid writing complements the simplicity of the Lovings’ wish — to be allowed to marry. Some of the wording, though, strikes a sour note. “Richard Loving was a good, caring man; he didn’t see differences,” she writes, suggesting, implausibly, that he did not notice Mildred’s race. After Mildred is identified as part black, part Cherokee, we are told that her race was less evident than her small size — that town folks mostly saw “how thin she was.” This language of colorblindness is at odds with a story about race. In fact, this story presents a wonderful chance to address the fact that noticing race is normal. It is treating people better or worse on the basis of that observation that is a problem.

And on March 18, 2015, I wrote a long review, focusing on Mildred Jeter's identity. I concluded with this:

In The Case for Loving, Alko uses "part African-American, part Cherokee" but I suspect Jeter's family would object to what Alko said. As the 2004 interview indicates, Mildred Jeter Loving considered herself to be Rappahannock. Her family identifies as Rappahannock and denies any Black heritage. This, Coleman writes, may be due to politics within the Rappahannock tribe. A 1995 amendment to its articles of incorporation states that stated (p. 166):

“Applicants possessing any Negro blood will not be admitted to membership. Any member marrying into the Negro race will automatically be admonished from membership in the Tribe.”

I'm not impugning Jeter or her family. It seems to me Mildred Jeter Loving was caught in some of the ugliest racial politics in the country. As I read Coleman's chapter and turn to the rest of her book, I am unsettled by that racial politics. In the final pages of the chapter, Coleman writes (p. 175):

"Of course, Mildred had a right to self-identify as she wished and to have that right respected by others. Nevertheless, viewed within the historical context of Virginia in general and Central Point in particular, ironically, “the couple that rocked courts” may have inadvertently had more in common with their opponents than they realized. Mildred’s Indian identity as inscribed on her marriage certificate and her marriage to Richard, a White man, appears to have been more of an endorsement of the tenets of racial purity rather than a validation of White/ Black intermarriage as many have supposed."

Turning back to The Case for Loving, I pick it up and read it again, mentally replacing Cherokee with Rappahannock and holding all this racial politics in my head. It makes a difference.

At this moment, I don't know what it means for this picture book. One could argue that it provides children with an important story about history, but I can also imagine children looking back on it as they grow up and thinking that they were misinformed--not deliberately--but by those twists and turns in racial politics in the United States of America.

Fast forward to last week (November 4, 2015), when I learned that changes were made to

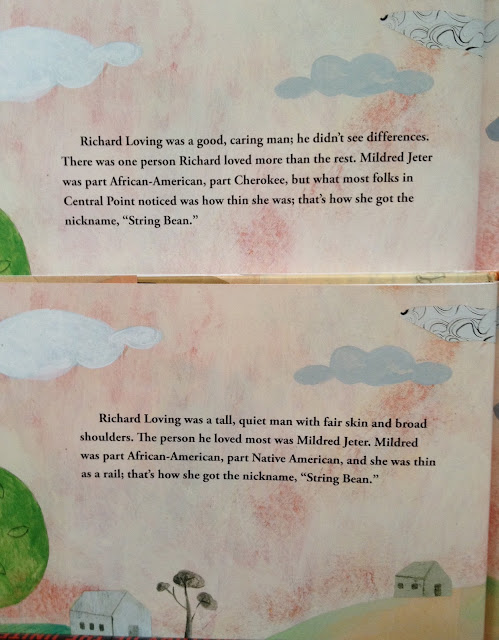

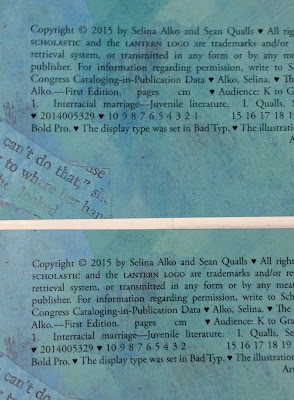

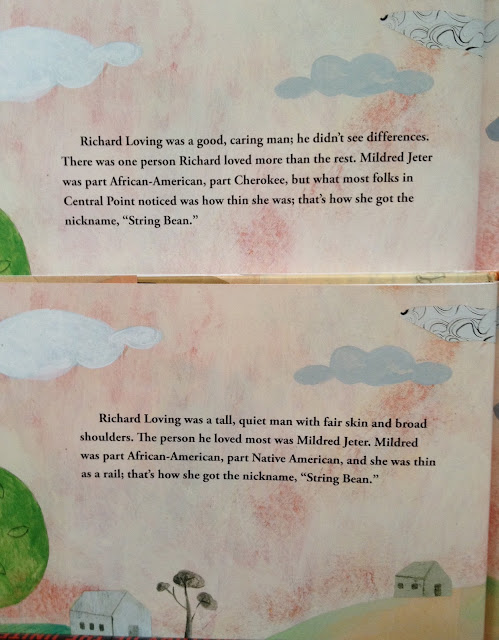

The Case for Loving in its second printing. Here's a photo of the copyright page for the two books. Look at the second line from the bottom in the top image. See the string of numbers that starts at 10 and goes on down to 1? That string is data. The lowest numeral in the string is 1, which tells us that the book with the 1 is the original. Now look at the second line from the bottom in the bottom image. See the string of numbers ends with numeral 2? That tells us that is the 2nd printing.

I learned about the second printing by watching Daniel Jose Older's video,

Full Panel: Lens of Diversity: It is Not All in What You See. Sean Qualls, illustrator of

The Case for Loving was also on that panel, which was slated as an opportunity to talk about Rudine Sims Bishop's idea of literature as windows, mirrors, and doors, framed around Sophie Blackall's art for the New York public transit system. The moderator and panel organizer, Susannah Richards, said that she saw people using social media to say that they thought they say themselves in Blackall's art. (To read more about the discussions of Blackall's picture book,

A Fine Dessert, see

Not recommended: A Fine Dessert.)

At approximately the 34:00 minute mark in Older's video, Richards began to speak about

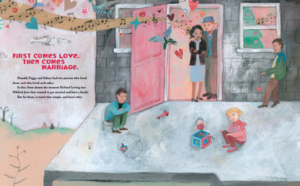

The Case for Loving and how Qualls and Alko addressed concerns about the book. Richards had a power point slide ready comparing a page in the original book with a page in the revised edition. It is similar to the one I have here (in her slide, she has the revised version at the top and the original on the bottom):

Qualls said "So, part of what happened is... There is a page with a description of Mildred and Richard." Qualls then read the revised page and the original one, too: "Richard was a tall quiet man with fair skin and broad shoulders. The person he loved most was Mildred Jeter. Mildred was part African-American, part Native American, and she was thin as a rail; that's how she got the nickname, String Bean. Richard Loving was a good, caring man; he didn't see differences. There was one person Richard loved more than the rest. Mildred Jeter was part African-American, part Cherokee, but what most folks in Central Point noticed was how thin she was; that's how she got the nickname, "String Bean."

|

| Reese's photo of original (on top) and revised (on bottom) page in THE CASE FOR LOVING |

For now, I'm going to step away from the video and Quall's remarks in order to compare the original lines on the page with the revised ones:

(1)

Original: Richard Loving was a good, caring man; he didn't see differences.

Revision: Richard Loving was a tall, quiet man with fair skin and broad shoulders.

See that change? "he didn't see differences" is gone. This, I think, is the result of Russell-Brown (of the

Times) saying that him not seeing difference was implausible, especially since this book is about race.

(2)

Original: There was one person Richard loved more than the rest.

Revision: The person he loved most was Mildred Jeter.

I don't know what that sentence was changed, and welcome your thoughts on it.

(3)

Original: Mildred Jeter was part African-American, part Cherokee...

Revision: Mildred was part African-American, part Native American...

In my review back in March, I said it was wrong to describe her as being part Cherokee, because on the application for a marriage license (dated May 24, 1958), she stated she was Indian. I assume the change to "Native American" rather than "Indian" was done because the person(s) weighing in on the change thought that "Indian" was pejorative. It can be, depending on how it is used, but I use it in the name of my site and it is used by national associations, too, like the National Congress of American Indians or the National Indian Education Association or the American Indian Library Association.

I think it would have been better to use Indian--and nothing else--because that is what Jeter used. "Native American" didn't come into use until the 1970s, as indicated at the Bureau of Indian Affairs website and other sources I checked. In order to tell this story as determined by the Supreme Court case, Alko and Qualls had to include "part African American" because that is the basis on which the case went to the Supreme Court in the first place. I'll say more about all of this below.

(4)

Original: ...but what most folks in Central Point noticed was how thin she was;

Revision: ...and she was thin as a rail;

I think this change is similar to (1). People do notice race.

(5)

Original: ...that's how she got the nickname, "String Bean."

Revision: ...that's how she got the nickname, "String Bean."

No change there, which is fine.

~~~~~~~~~

Now I want to return to the video, and look more closely at (3) -- how Alko and Qualls describe Jeter.

After reading aloud the original and revised passage, Qualls paused. The moderator, Susannah Richards, stepped in. Here's a transcript:

Richards: "Research is complicated, and in researching this particular book, and looking... And even having some of my law friends look at it, they were like 'well some things say she was Cherokee and some things say she was wasn't, some things say her birth certificate said this,' and... There was just a lot of information out there."

Qualls: "Right. And I think that Deborah..."

Richards: "Debbie Reese."

Qualls: "Debbie Reese..."

Richards: "Who many of you may follow on her blog."

Qualls: "Really brought issue with the Cherokee description of Mildred, and, I have spoken to at least some family members and no one really seems to know whether she was Cherokee or Rappahannock. And I think there are some... Debbie Reese may have said, or somewhere I read, that Mildred claimed not to have any African American heritage. But then I've also read that the Rappahannock Nation is less likely to recognize someone as Rappahannock if they claim to have any African American heritage. We're also talking about the 1950s and 1960s where it may have been convenient for someone to claim that they had no African American heritage. James Brown, of all people, claimed he was part Japanese, part Native American, and had no African American heritage. So, it is extremely loaded, and yeah, you know, I really don't know what to say about it. And, it comes down to ones intention, and you know, in trying to represent diversity, and the fact is, no one really knows what her back ground was. I believe that she was part African American. My gut tells me that. She looks that way, she feels that way when I see her, when I see videos of her. So, yeah, that became a little bit of a controversy and was very disturbing to my wife, who is Canadian in origin, and the fact that you're Australian, you know, its very interesting. There are two people that I know that include and have always included African Americans in their art, and without question, that's really important, I think.

Qualls is right, of course. I did raise a question about them identifying Jeter as Cherokee.

I'm curious about his next comment, that he has spoken to family members who say that no one really knows whether she was Cherokee or Rappahannock. In my review, I quoted Coleman's 2004 interview of Jeter, in which she said "I am not Black. I have no Black ancestry. I am Indian-Rappahannock." I didn't include this passage (below) but am including it now--not as a deliberate attempt to argue with Qualls--but because I am committed to helping people understand Native nationhood and how Native people speak of their identity. Coleman writes (p. 173):

The American Indian identity is strong within the Loving family as demonstrated by Mildred’s grandson, Marc Fortune, the son of her daughter Peggy Loving Fortune. When Mildred Loving’s son, Donald, died unexpectedly on August 31, 2000, Marc, according to one attendee, arrived at his uncle’s funeral dressed in native regalia and performed a “traditional Rappahannock” ritual in honor of his deceased uncle. In fact, all of the Loving children are identified as Indian on their marriage licenses. During an interview on April 10, 2011, Peggy Loving stated that she is “full Indian.” This was also the testimony of her uncle, Lewis Jeter, Mildred’s brother who stated during an interview on July, 20, 2011, that the family was Indian and not Black. Echoing his sister’s words he stated, “We have no Black ancestry that I know of.”

Based on all I've read and many conversations with people who do not understand the significance of saying you're a member or citizen of a specific tribe, here's what I think is going on.

In watching videos of Jeter, Qualls said that he believes Jeter was part African American. In the video, he said "She looks that way, she feels that way when I see her, when I see videos of her." He is basing that, I believe, on her

physical appearance rather than on her own words about her citizenship in the Rappahannock Nation. Qualls is conflating a racial identity with a political one.

I'm not critical of Qualls for thinking that way. I think most Americans would think and say the same thing he did. That is because Native Nationhood is not taught in schools. It should be, and it should be part of children's books, too, because our membership or citizenship in our nations is a fact of who we are. Indeed, it is the most significant characteristic of who we are, collectively. It is why our ancestors made treaties with leaders of other nations. It is why we, today, have jurisdiction of our homelands.

All across the U.S., there are peoples of varying physical appearance who are citizens of a Native nation. My paternal grandfather is white. He was not a tribal member. My dad and my uncle are tribal members. Myself and my siblings, though we range in appearance (I have the darkest hair and skin tone amongst us), are all tribal members. On the federal census, we say we're tribal members and we specify our nation as Nambe Pueblo. Our political identity is a Native one. Because of our grandfather, some of us look like we're mixed bloods, because we are, but when asked, we say we are tribal members, and we say that, too, on the U.S. census documents. We were raised at Nambe and we participate in a range of tribally-specific activities, from ceremonies to civic functions such as community work days and elections. What we look like, physically, is not important.

In short, the revision regarding Jeter's identity is based on a physical description rather than a political one. My speculation: the author, illustrator, and their editor do not know enough about Native nationhood to understand why that distinction matters.

Now let's take a look at the content of the reviews.

The reviewers at

School Library Journal, Kirkus echoed the book, saying that Mildred was African American and Cherokee. The reviewer at

Publisher's Weekly did not say anything about her identity. Horn Book's reviewer said "Richard Loving (white) and Mildred Jeter (black) fell in love and married..." Not surprisingly, then, that the Horn Book reviewer tagged it with "African Americans" as a subject, and not Native American, but I'm curious why they ignored her Native identity? Did they choose to view the Loving case as one about interracial marriage between a White man and Black woman--as the Loving's lawyers did? Perhaps.

In Older's video, he says that there are some stories that he wouldn't touch. I think the Loving case is one that is more complicated than a picture book for young children can do justice to. Here's key points, from my point of view:

In the 1950s, Mildred Jeter said she was Indian. We don't know if she said that out of a desire to avoid being discriminated against, or if she said that because she was already living her life as one in which she firmly identified as being Indian. Either way, it is what she said about who she was on the application for a marriage license.

In the 1960s, because Mildred Jeter and Richard Loving's marriage violated miscegenation laws, their case went before the Supreme Court of the United States. To most effectively present their case, the emphasis was on her being Black.

In the 2000s, Jeter and her children said they are Indian, and specified Rappahannock as their nation.

In the 2000s, Alko and Qualls met and fell in love.

In the 2010s, Alko and Qualls worked together on a picture book about the Lovings. In the author's note for

The Case for Loving, Alko said that she's a white Jewish woman from Canada, and that Sean is an African American man from New Jersey. She said that much of her work is about inclusion and diversity and that it is difficult for her to imagine that just decades ago, couples like theirs were told by their governments, that their love was not lawful. For years, Alko writes, she and Qualls had thought about illustrating a book together.

The Case for Loving is that book.

I think it is fair to say that the love they have for each other was a key factor in the work they did on

The Case for Loving, but who they are is not who the Lovings were. That fact meant they could not--and can not--see Mildred for who she is.

My husband and I are also a couple in an interracial marriage. He's White; I'm Native. If we were an author/illustrator couple working in children's books and wanted to do a story about the Lovings, we'd enter it from a different place of knowing. We both know the importance of Native nationhood and the significance of Nambe's status as a sovereign nation. He didn't know much about Native people until he started teaching at Santa Fe Indian School, where we met in 1988 when I started teaching there. What we do not have is a lived experience or knowledge of the life of Mildred Jeter as she lived her life in the 1950s in Virginia. We'd be doing a lot of research in order to do justice to who she was.

At the end of his remarks (in the video) about

The Case for Loving, Qualls said that it comes down to intentions, and that his wife and Sophie Blackall are very careful to include diversity in their work. He said he thinks it is important. I don't think anyone would disagree with that statement. Diversity is important. But, as his other remarks indicate, he's since learned how complicated the discussion of Jeter's identity were, then and now, too. They've revised that page in the book but as you may surmise, I think the revision is still a problem.

I like the art very much and think it is important for young children to know about the Lovings and families in which the parents are of two different demographics. I'll give some thought to how it could be revised so that it sets the record straight, and I welcome your thoughts (and do always let me know--as usual--about typos or parts of what I've said that lack clarity or are confusing).

Pick up a copy of

That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans, and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia, published in 2013 by Indiana University Press. Read the chapter on the Lovings, and read Alko and Qualls and see what you think. Can it be revised again? How?

This has been quite the year in children's literature--and I say that in a good way. Some people are decrying social media, but I celebrate it. It is making a difference.

Some say social media that questions books like A Fine Dessert is unfairly attacking the author and illustrator. Some say the creators of the book are being publicly shamed. Roger Sutton said that about the change made to Amazing Grace.

But you know who has been publicly shamed

for decades and decades?

Children.

Children whose culture is misrepresented or poorly

represented in popular, classic, and award-winning books.

In his new book,

Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton, Don Tate's note in the back is important. He writes:

When I first began illustrating children's books, I decided that I would not work on stories about slavery. I had many reasons, one being that I wanted to focus on contemporary stories relevant to young readers today. In all honesty, though, what I wasn't admitting to myself was that I was ashamed of the topic.

I grew up in a small town in the Midwest in the 1970s and 1980s. At school, I was usually the only brown face in a sea of white. It seemed to me that whenever the topic of black history came up, it was always in relation to slavery, about how black people were once the property of white people--no more human than a horse or a wheelbarrow. Sometimes white kids snickered and made jokes about the topic. Sometimes, black kids did too.

A wash of emotion floods over me each time I read Don's words. I've heard similar things from Native kids and teens, too. Don takes up the topic of slavery in

Poet. But he does it with a full understanding of what it feels like to be a black child reading a book that depicts slavery.

I have no doubt that Emily Jenkins and Sophie Blackall meant well when they created

A Fine Dessert, but they and the community of people who worked with them on the book created it from within a space that doesn't have what Don has. The outcome, as most of us know, has caused an enormous discussion on social media.

I have empathy for Jenkins and Blackall, but as my larger text above makes clear, my empathy is with children. Because of social media, Jenkins, Blackall, and anyone who is following this discussion, have heard from people they don't normally hear from. People who aren't in their community. In this case, African American parents who are stunned with the depiction of slavery in

A Fine Dessert. Some of the response has been blistering in its anger. Jenkins has heard them, and subsequently, apologized.

Thus far, Blackall has not. She says she's heard them, but what does it mean when you hear someone--with reason or with fury--tell you that you've hurt them, but all you do is rebut what they say? I don't know what to call that response.

She and people who are empathizing with her are decrying social media, but I celebrate what it is doing right now in children's literature. Because of it, I have a blog that people read. They link to it. They reference it. They assign it. They share it. The outcome? People write to tell me what they're learning.

Because of social media, we can all watch a video of a panel discussion that took place last weekend. A discussion--I think--that has never happened before at a conference. I'm asking my colleagues who research children's literature. Nobody recalls one like this before.

Sean Qualls, Sophie Blackall, and Daniel Jose Older spoke on a panel titled "Lens of Diversity: It is Not All in What You See" at the New York City School Library System's 26th annual conference. I'm studying the video and will have more to say about it later, but for now, watch it yourself.

I'll be back with a post about it later. For now I've got to finish preparing a talk I'll be giving for Chicago Public Library tomorrow. I was shaken to the core as I watched the video. Shaken by the denial of Qualls and Blackall, and shaken by the honesty of Older. He is using social media to effect change. Change is happening. I know that change is happening because of the email I get from gatekeepers.

I think we're in the crisis that Walter Dean Myers anticipated in 1986 in his

New York Times article,

I Thought We Would Actually Revolutionize the Industry. He wrote about how the 1970s looked like a turning point:

...the quality of the books written by blacks in the 70's was so outstanding that I actually thought we would revolutionize the industry, bringing to it a quality and dimension that would raise the standard for all children's books. Wrong. Wrong. Wrong. No sooner had all the pieces conducive to the publishing of more books on the black experience come together than they started falling apart.

This time round, I think things will not fall apart. Social media is driving change in children's literature. And so, I celebrate it.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 7/1/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

nonfiction picture books,

Scholastic,

Best Books,

Arthur A. Levine,

Sean Qualls,

Selina Alko,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 reviews,

2015 nonfiction picture books,

Add a tag

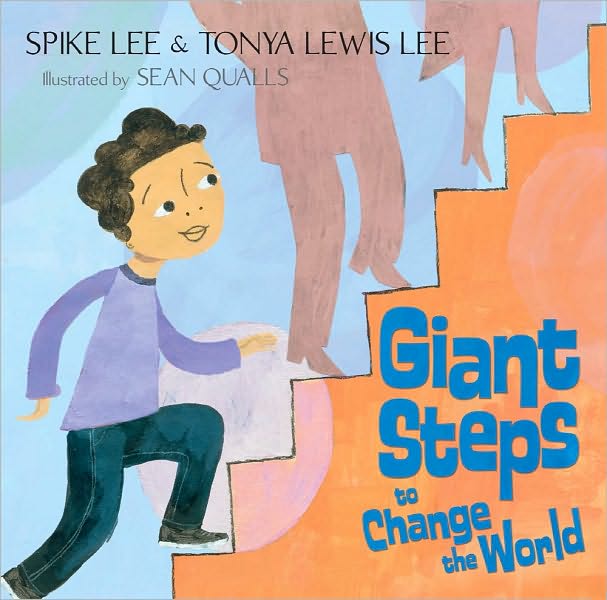

The Case for Loving: The Fight for Interracial Marriage

The Case for Loving: The Fight for Interracial Marriage

By Selina Alko

Illustrated by Sean Qualls

Arthur A. Levine Books (an imprint of Scholastic)

$18.99

ISBN: 978-0545478533

Ages 4-7

On shelves now.

When the Supreme Court ruled on June 26, 2015 that same-sex couples could marry in all fifty states, I found myself, like many parents of young children, in the position of trying to explain the ramifications to my offspring. Newly turned four, my daughter needed a bit of context. After all, as far as she was concerned gay people had always had the right to marry so what exactly was the big deal here? In times of change, my back up tends to be children’s books that discuss similar, but not identical, situations. And what book do I own that covers a court case involving the legality of people marrying? Why, none other than The Case for Loving: The Fight for Interracial Marriage by creative couple Selina Alko and Sean Qualls. It’s almost too perfect that the book has come out the same year as this momentous court decision. Discussing the legal process, as well as the prejudices of the time, the book offers to parents like myself not just a window to the past, but a way of discussing present and future court cases that involve the personal lives of everyday people. Really, when you take all that into consideration, the fact that the book is also an amazing testament to the power of love itself . . . well, that’s just the icing on the cake.

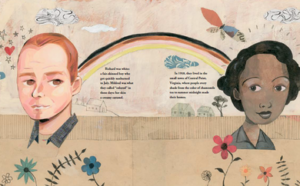

In 1958 Richard Loving, a white man, fell in love with Mildred Jeter, a black/Native American woman. Residents of Virginia, they could not marry in their home state so they did so in Washington D.C. instead. Then they turned right around and went home to Virginia. Not long after they were interrupted in the night by a police invasion. They were charged with “unlawful cohabitation” and were told in no uncertain terms that if they were going to continue living together then they needed to leave Virginia. They did, but they also hired lawyers to plead their case. By 1967 the Lovings made it all the way to The Supreme Court where their lawyers read a prepared statement from Richard. It said, “Tell the court I love my wife, and it is just unfair that I can’t live with her in Virginia.” In a unanimous ruling, the laws restricting such marriages were struck down. The couple returned to Virginia, found a new house, and lived “happily (and legally) ever after.” An Author’s Note about her marriage to Sean Qualls (she is white and he is black) as well as a note about the art, Sources, and Suggestions for Further Reading appear at the end of the book.

“How do you sue someone?” Here’s a challenge. Explain the concept of suing the government to a four-year-old brain. To do so, you may have to explain a lot of connected concepts along the way. What is a lawyer? And a court? And, for that matter, why are the laws (and cops) sometimes wrong? So when I pick up a book like The Case for Loving as a parent, I’m desperately hoping on some level that the authors have figured out how to break down these complex questions into something small children can understand and possibly even accept. In the case of this book, the legal process is explained as simply as possible. “They wanted to return to Virginia for good, so they hired lawyers to help fight for what was right.” And then later, “It was time to take the Loving case all the way to The Supreme Court.” Now the book doesn’t explain what The Supreme Court was necessarily, and that’s where the art comes in. Much of the heavy lifting is done by the illustrations, which show the judges sitting in a row, allowing parents like myself the chance to explain their role. Here you will not find a deep explanation of the legal process, but at least it shows a process and allows you to fill in the gaps for the young and curious.

“How do you sue someone?” Here’s a challenge. Explain the concept of suing the government to a four-year-old brain. To do so, you may have to explain a lot of connected concepts along the way. What is a lawyer? And a court? And, for that matter, why are the laws (and cops) sometimes wrong? So when I pick up a book like The Case for Loving as a parent, I’m desperately hoping on some level that the authors have figured out how to break down these complex questions into something small children can understand and possibly even accept. In the case of this book, the legal process is explained as simply as possible. “They wanted to return to Virginia for good, so they hired lawyers to help fight for what was right.” And then later, “It was time to take the Loving case all the way to The Supreme Court.” Now the book doesn’t explain what The Supreme Court was necessarily, and that’s where the art comes in. Much of the heavy lifting is done by the illustrations, which show the judges sitting in a row, allowing parents like myself the chance to explain their role. Here you will not find a deep explanation of the legal process, but at least it shows a process and allows you to fill in the gaps for the young and curious.

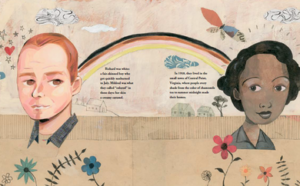

It was very interesting to me to see how Alko and Qualls handled the art in this book. I’ve often noticed that editors like to choose Sean as an artist when they want an illustrator that can offset some of the darker aspects of a work. For example, take Margarita Engle’s magnificently sordid Pura Belpre Medal winner The Poet Slave of Cuba. A tale of torture, gore, and hope, Qualls’ art managed to represent the darkness with a lighter touch, while never taking away from the important story at hand. In The Case for Loving he has scaled the story down a bit and given it a simpler edge. His characters are a bit broader and more cartoonlike than those in, say, Dizzy. This is due in part to Alko’s contributions. As they say in their “About the Art” section at the back of the book, Alko’s art is all about bold colors and Sean’s is about subtle layers of color and texture. Together, they alleviate the tension in different scenes. Moments that could be particularly frightening, as when the police burst into the Lovings’ bedroom to arrest them, are cast instead as simply dramatic. I noticed too that characters were much smaller in this book than they tend to be in Sean’s others. It was interesting to note the moments when that illustrators made the faces of Richard and Virginia large. The page early in the book where Richard and Mildred look at one another over the book’s gutter pairs well with the page later in the book where their faces appear on posters behind bars against the words “Unlawful Cohabitation”. But aside from those two double spreads the family is small, often seen just outside their different respective homes. It seemed to be important to Qualls and Alko to show them as a family unit as often as possible.

Few books are perfect, and Loving has its off-kilter moments from time to time. For example, it describes darker skin tones in terms of food. That’s not a crime, of course, but you rarely hear white skin described as “white as aged cheese” or “the color of creamy mayonnaise” so why is dark colored skin always edible? In this book Mildred is “a creamy caramel” and she lives where people ranged from “the color of chamomile tea” to darker shades. A side issue has arisen concerning Mildred’s identification as Native American and whether or not the original case made more of her African-American roots because it would build a stronger case in court. This is a far bigger issue than a picture book could hope to encompass, though I would be interested in a middle grade or young adult nonfiction book on the topic that went into the subject in a little more depth.

Few books are perfect, and Loving has its off-kilter moments from time to time. For example, it describes darker skin tones in terms of food. That’s not a crime, of course, but you rarely hear white skin described as “white as aged cheese” or “the color of creamy mayonnaise” so why is dark colored skin always edible? In this book Mildred is “a creamy caramel” and she lives where people ranged from “the color of chamomile tea” to darker shades. A side issue has arisen concerning Mildred’s identification as Native American and whether or not the original case made more of her African-American roots because it would build a stronger case in court. This is a far bigger issue than a picture book could hope to encompass, though I would be interested in a middle grade or young adult nonfiction book on the topic that went into the subject in a little more depth.

Recently I read my kid another nonfiction picture book chronicling injustice called Drum Dream Girl by the aforementioned Margarita Engle. In that book a young girl isn’t allowed to drum because of her gender. My daughter was absolutely flabbergasted by the notion. When I read her The Case for Loving she was similarly baffled. And when, someday, someone writes a book about the landmark decision made by The Supreme Court to allow gay couples to wed, so too will some future child be just as floored by what seems completely normal to them. Until then, this is certainly a book written and published at just the right time. Informative and heartfelt all at once, it works beyond the immediate need. Context is not an easy thing to come by when we discuss complex subjects with our kids. It takes a book like this to give us the words we so desperately need. Many thanks then for that.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Misc: Don’t forget to check out this incident that occurred involving this book and W. Kamau Bell’s treatment at Berkeley’s Elmwood Café.

New this year (2015) is

The Case for Loving: The Fight for Interracial Marriage by Selina Alko. Illustrations are by Alko and her husband, Sean Qualls.

The author's note tells us that Alko is a "white Jewish woman from Canada" and that Qualls is an "African-American man from New Jersey."

The story of Mildred Jeter and Richard Loving resonated with Alko and Qualls. Their case went before the United States Supreme Court in 1967. Here's the synopsis posted at Scholastic's website:

For most children these days it would come as a great shock to know that before 1967, they could not marry a person of a race different from their own. That was the year that the Supreme Court issued its decision in Loving v. Virginia.

This is the story of one brave family: Mildred Loving, Richard Perry Loving, and their three children. It is the story of how Mildred and Richard fell in love, and got married in Washington, D.C. But when they moved back to their hometown in Virginia, they were arrested (in dramatic fashion) for violating that state's laws against interracial marriage. The Lovings refused to allow their children to get the message that their parents' love was wrong and so they fought the unfair law, taking their case all the way to the Supreme Court — and won!

The Loving case is of interest to me, too. We all ought to embrace its outcome. As the synopsis indicates, the story is about the love Jeter and Loving had for each other, and how, using the court system, laws against their desire to be married were struck down. We need to know that history. It is important. In her

review in the New York Times, Katheryn Russell-Brown noted its strengths. She also said something I agree with:

Alko’s calm, fluid writing complements the simplicity of the Lovings’ wish — to be allowed to marry. Some of the wording, though, strikes a sour note. “Richard Loving was a good, caring man; he didn’t see differences,” she writes, suggesting, implausibly, that he did not notice Mildred’s race. After Mildred is identified as part black, part Cherokee, we are told that her race was less evident than her small size — that town folks mostly saw “how thin she was.” This language of colorblindness is at odds with a story about race. In fact, this story presents a wonderful chance to address the fact that noticing race is normal. It is treating people better or worse on the basis of that observation that is a problem.

As Russell-Brown noted, the "language of colorblindedness" doesn't work. As a grad student in the 90s, I read

research that found that the colorblind approach sent the opposite message to young children.

The Case for Loving also provides us with an opportunity to look at identity and claims to Native identity.

When I first learned that Alko and Qualls presented Mildred Jeter as part Cherokee (as shown in the image to the right), I started doing some research on her and the case. In some places I saw her described as Cherokee. In a few others, I saw her described as Cherokee and Rappahannock. That made me more intrigued! In the midst of that research, I also

re-read Cynthia Leitich Smith's Rain Is Not My Indian Name and really appreciate--and recommend it--for lots of reasons, including how Smith wrote about Black Indians.

I continued my research on Jeter and found a particularly comprehensive source:

That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans, and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia by

Arica L. Coleman. It was published in 2013. Coleman's book has a chapter about Jeter.

Drawing from magazines, newspapers and court documents of that time and more recently, too, Coleman describes the twists and turns that impacted Mildred Jeter's identity. Most crucial to her chapter is information Jeter gave to her.

Jeter did not identify herself as Black. In an interview on July 14, 2004, she told Coleman (p. 153):

"I am not Black. I have no Black ancestry. I am Indian-Rappahannock."

In

The Case of Loving, we read about Mr. and Mrs. Loving going to Washington DC to get married, returning home to Virginia with their marriage license, and, being awoken late one night by the police who asked Richard what he was doing in bed with Jeter.

He pointed to their marriage certificate hanging on the wall.

The marriage certificate--an image of which is in Coleman's book--shows us columns for the male and female applying for the license. Here's the information in the female column:

Name: Mildred Delores Jeter

Color: Indian

She identified as Indian. In Central Point (that's the town they lived in), Coleman writes, there was a (page 161-162):

"racial hierarchy that granted social privileges to Whites, an honorary White privilege to Indians (i.e. access to White hospitals and the White only section of rail and street cars), and no social privilege to Blacks."

Isn't that fascinating? There's more. In 1870, Mildred's parents were listed on census records as mulatto. By 1930, they were identified as Negro. She was born in 1939. But, Coleman writes (p. 164):

The Jeter surname is also listed in the Rappahannock Tribe’s corporate charter (1974) as a tribal affiliate. Many claim, however, that the Jeters are descended from the Cherokee who allegedly began to intermarry with the Rappahannock during the late eighteenth century. According to one anonymous informant, “The situation regarding Indian identity in Caroline County is very complex. There was a time when many in the Rappahannock community believed that they were Cherokee because that was all they knew.” Neither Mildred nor her brother, Lewis Jeter, supported the claim that their father was Cherokee.

A 1997 article in the

Free Lance-Star reports that she said she was Indian, with Portuguese and Black ancestry. In 2004 Coleman asked her about the Black ancestry, prefacing her question with a reference to the Rappahannock's historic association with Blacks, Jeter told Coleman that the Rappahannock's never had anything to do with Blacks.

That denial of Black ancestry is striking, particularly since the Supreme Court case was based on her being Black. If I understand Coleman's research, Jeter thought of herself as Indian when she married Loving. When their case went before the Supreme Court, she was regarded as Black. In the last years of her life, she said she was Indian. What was going on?

Her ACLU lawyers, Bernard Cohen and Philip Hirschkop, and Virginia's Assistant Attorney General, Robert McIlwaine--needed her to be Black. Her Indian identity had the potential to derail the arguments they were putting forth.

See, there was an act in Virginia called the "Racial Integrity Act" that was intended to preserve the purity of the White race. In early drafts of that act, white meant a person having only Caucasian blood. But that definition was replaced by the "Pocahontas Exception." The

Racial Integrity Act was passed in 1924.

When I read "Pocahontas Exception" --- well, I think it fair to say that my eyebrows shot up and that I leaned towards the screen (reading an e-copy of the book)! What is THAT?!

The Pocahontas Exception allowed Whites to claim to be white, as long as they had no more than 1/16 of the blood of an American Indian.

Chief Justice Earl Warren was presiding over the Loving case. Presumably, he knew about her Indian identity and therefore asked about the Pocahontas Exception. I hope I am correct in my reading of Coleman's research when I say that Warren let it go when he heard McIlwaine's reply to his questions. The law, McIlwaine argued, did not apply to this case because Virginia had two populations of significance to its legislature: a bit over 79% were white and a bit over 20% were colored; therefore, the number of Native people (at less than 1%) was insignificant. Moreover (p. 170):

It is a matter of record, agreed to by all counsel during the course of this litigation and in the brief that one of the appellants here is a white person within the definition of the Virginia law, the other appellant is a colored person within the definition of Virginia law.

Significant/insignificant are my word choices. McIlwaine didn't use them and neither did Coleman. They are words that resonate with Native people because research studies on race typically have an asterisk rather than data for us, because relative to other demographics, we are deemed too small to count. Indeed, a group of Native scholars have written a book about some of this, titled

Beyond the Asterisk: Understanding Native Students in Higher Education.

With intricate detail, Coleman documents how the news media was hit-or-miss in terms of what reporters said about Jeter's race. One day it was "negro" and the next--in the same paper--it was "half negro, half Indian" and then later on, it was back to "negro." In the final analysis, Coleman writes, writers generally describe her as an "ordinary Black woman" (p. 173):

In

The Case for Loving, Alko uses "part African-American, part Cherokee" but I suspect Jeter's family would object to what Alko said. As the 2004 interview indicates, Mildred Jeter Loving considered herself to be Rappahannock. Her family identifies as Rappahannock and denies any Black heritage. This, Coleman writes, may be due to politics within the Rappahannock tribe. A1995 amendment to its articles of incorporation states that stated (p. 166):

“Applicants possessing any Negro blood will not be admitted to membership. Any member marrying into the Negro race will automatically be admonished from membership in the Tribe.”

I'm not impugning Jeter or her family. It seems to me Mildred Jeter Loving was caught in some of the ugliest racial politics in the country. As I read Coleman's chapter and turn to the rest of her book, I am unsettled by that racial politics. In the final pages of the chapter, Coleman writes (p. 175):

Of course, Mildred had a right to self-identify as she wished and to have that right respected by others. Nevertheless, viewed within the historical context of Virginia in general and Central Point in particular, ironically, “the couple that rocked courts” may have inadvertently had more in common with their opponents than they realized. Mildred’s Indian identity as inscribed on her marriage certificate and her marriage to Richard, a White man, appears to have been more of an endorsement of the tenets of racial purity rather than a validation of White/ Black intermarriage as many have supposed.

Turning back to

The Case for Loving, I pick it up and read it again, mentally replacing Cherokee with Rappahannock and holding all this racial politics in my head. It makes a difference.

At this moment, I don't know what it means for this picture book. One could argue that it provides children with an important story about history, but I can also imagine children looking back on it as they grow up and thinking that they were misinformed--not deliberately--but by those twists and turns in racial politics in the United States of America.

Updates to add relevant items shared by others:

Kara Stewart pointed me to a news story from a Virginia TV station:

Doctor's quest to engineer a 'master race' in the early 1900s still hurting Virginia Indian tribes Kara's comment prompted me to search for information on the Racial Integrity Act. I found that the

Library of Virginia has a page about it.

Margaret Wise Brown, the author of the iconic children’s book Goodnight Moon, has a new collection of lullabies available from Sterling Children’s Books called Goodnight Songs.

Margaret Wise Brown, the author of the iconic children’s book Goodnight Moon, has a new collection of lullabies available from Sterling Children’s Books called Goodnight Songs.

Brown reportedly wrote these songs in 1952, just before she passed away and the works were recently discovered in a trunk in her sister’s farmhouse in Vermont.

The book features 12 songs, each illustrated by a different artist. Carin Berger the illustrator of The Little Yellow Leaf; Eric Puybaret, the artist that drew Puff, the Magic Dragon; Coretta Scott King Honor Award winner Sean Qualls; and Caldecott Honor medalist Melissa Sweet, each drew a song. The book comes with a CD with a recording of the songs set to music by Emily Gary and Tom Proutt. (Via NPR Books).

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

Qualls’s primitive-style collage illustrations strongly convey the depth of Brown’s emotions.-School Library Journal,

0 Comments on Much has happened in the past few months... as of 3/7/2012 7:18:00 AM

The Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books - Freedom Song: The Story of Henry “Box” Brown; illus. by Sean Qualls. Harper/HarperCollins, 2012 32p ISBN 978-0-06-058310-1 $17.99 R* 5-8yrs Ellen Levine and Kadir Nelson’s Henry’s Freedom Box (BCCB 4/07) sets the bar high for picture books about the Virginia slave who endured pummeling confinement in a crate as he had himself shipped to New York and freedom. Walker, inspired by the discovery that Henry Brown sang for many years in a church choir, takes a more poetic but equally successful tack, imagining that rhythm and song sustained Brown throughout his years of enslaved labor and inspired him to seek his freedom when his wife and children were sold away from Virginia. Walker infuses her text and Brown’s thoughts with patterned phrasing, from the “twist, snap, pick-a-pea” work songs he sang in the fields, to the “freedom-land, family, stay-together words” that comforted him as a child, to the “stay-still, don’t move, wait-to-be-sure words” that kept him silent as he waited for release from his shipping crate. Qualls’ mixed-media illustrations, far more dreamy and stylized than Nelson’s near-photorealistic renderings, are nonetheless an excellent match for Walker’s text. Even his signature aquas and pinks, embellished with free-floating bubbles, are tempered with more sober grays, browns, and deep blues, and weighted with heavily textured brushwork. An author’s note touches on Walker’s research and what little is known of Brown’s subsequent history; also appended is the fascinating text of a letter from Brown’s accomplice in 1849, detailing Brown’s escape and cautioning the recipient, “for Heaven’s sake don’t publish this affai or allow it to be published. It would . . . prevent all others from escaping in the same way.” EB

Photographers

Tribble & Mancenido photographed nine artists for

CODE Magazine. Check out the other eight artists

here. Many thanks to Tracey and James for including me and Peter Duhon for the interview.

By: Maryann Yin,

on 5/5/2011

Blog:

Galley Cat (Mediabistro)

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Edwin Fotheringham,

Children's Books,

Publishing,

children's illustrators,

Reading is Fundamental,

Scholastic,

Reach Out and Read,

Stephen Savage,

Sean Qualls,

Raina Telgemeier,

Read Every Day. Lead A Better Life.,

Barbara McClintock,

Bruce Degen,

Jeff Smith,

Clifford the Big Red Dog,

David Shannon,

Mary Grandpre,

Mark Teague,

Jon J. Muth,

Norman Bridwell,

Miss Frizzle,

Stillwater the Panda,

Add a tag

Scholastic has opened an auction to benefit its global literacy campaign, “Read Every Day. Lead A Better Life.”

Scholastic has opened an auction to benefit its global literacy campaign, “Read Every Day. Lead A Better Life.”

The auction features pieces created by twelve celebrated children’s illustrators: Norman Bridwell, Bruce Degen, Edwin Fotheringham, Mary GrandPré, Barbara McClintock, Jon J. Muth, Sean Qualls, Stephen Savage, David Shannon, Jeff Smith, Mark Teague, and Raina Telgemeier.

USA Today posted a slideshow with all twelve pieces of art. The money generated by the auction will go to two children’s literacy organizations, Reading Is Fundamental (RIF) and Reach Out and Read. The auction will close on June 5th.

continued…

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

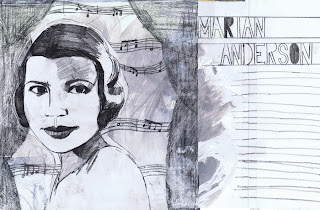

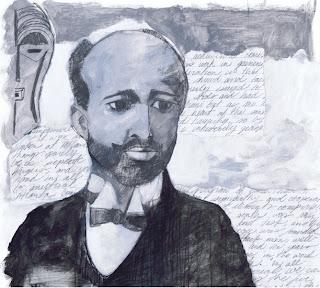

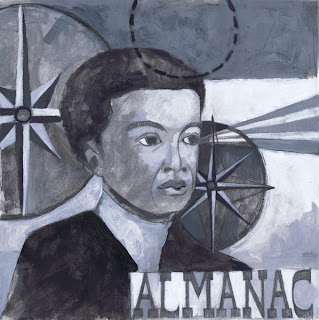

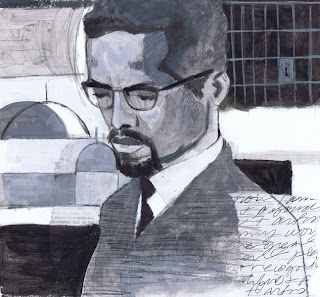

Day 28 of Black History Month.

Day 25 of Black History Month.

Day 24 of Black History Month.

Day 23 of Black History Month and Dubois' birthday.

Day 21 of Black History Month. Today is also Barbara Jordan's birthday.

special thanks to Rebecca Rent for the photo.

Day 17 of Black History Month.

Day 16 of Black History Month.

Day 15 of Black History Month.

-

SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 20th – 11AM

BOOKCOURT 163 Court St. (bet Pacific and Dean)

Day eleven of Black History Month.

Day eight of Black History Month.

Day seven of Black History Month.

I love original artwork. When I fall in love, there is no greater thrill for me than to be able to own an original piece that I can cherish always and forever. Years ago when I was gainfully employed as an art teacher, I stalked admired Kadir Nelson’s work (still do) and wished that I could afford one of his originals. One day, there was a painting that appeared on his web site titled “Rainbow”. It was a smaller painting, but was within my budget at only $1000 and I loved it. It spoke to me (cue the wind chimes). The image was a close up of a woman’s face with a rainbow painted across her eyelid. I waited and waited to buy it, debating whether or not I could make that type of investment. When I finally mustered up the courage to purchase the painting it was gone. To this day it is one of my biggest regrets. Now it haunts me (cue the weepy violins).

Since then I vowed to seize opportunities to purchase original art when I can.

That being said, 826LA held an OH NO art auction with Dan Santat back in August. I saw that Sean Qualls (who I also stalk admire) had a piece up for bidding and I jumped at the chance to own it. A few days went by and I won the piece! Happy Day!!!

Not only did I get to add a new piece of art to my (modest) collection and a signed copy of Dan’s awesome book, OH NO! (Or, How my Science Project Destroyed the World), with a signed limited edition print, but I was also supporting 826LA, a non-profit organization that provides free literacy programs to thousands of students living in underserved neighborhoods in Los Angeles.

Scholastic has opened an auction to benefit its global literacy campaign, “

Scholastic has opened an auction to benefit its global literacy campaign, “

Oh dear, Betsy. How a person chooses to identify who they are is not a “side issue.” Yes, it is a very complicated discussion for a picture book to take on, but at the very least, the book should not say she was part Cherokee, thereby giving incorrect information to the millions of young children, parents, librarians, and teachers who will read this book.

For those interested in knowing more about Jeter’s identity, please visit my post about it:

http://americanindiansinchildrensliterature.blogspot.com/2015/03/the-case-for-loving-by-selina-alko-and.html

Posting again, Betsy, because I think you are–inadvertently–doing that thing where Native concerns are dismissed because the larger message of a book is more important. Doing that, in effect, further marginalizes an already marginalized population.

Your post is especially troubling in light of conversations going on right now about Native identity–Cherokee identity, in particular. The conversation was prompted by an article in the Daily Beast about Andrea Smith’s claims to Cherokee identity. Smith has been a key figure in Native and Women’s studies for a long time. Day in and day out, the Cherokee people are misused and misrepresented. Jeter didn’t do that, and it is wrong to let someone misrepresent her, in 2015.

Identity matters.

Oops! Posted a response to you on Facebook then saw that you’d commented here. Doubling back.

Well it’s something I struggled with certainly. Having read your piece on the book I wanted to understand why the statement that Jeter was multiracial was inappropriate. I’m still trying to understand it, to be frank. From your piece I see that she was multiracial and identified as Native and that the ACLU preferred to portray her as mostly African-American. Yet in the book itself, she is never identified as primarily black. It does put the case in the context of the segregated south and, as you pointed out, the laws regarding interracial marriages between Native Americans and Anglo-Americans were different from those between African Americans and whites. That said, she was partially African-American and so the laws did apply to her. If that is incorrect let me know, since obviously I haven’t studied up on this to the extent that you have. The book is concentrating primarily on the court case and not Jeter’s life, so when I called it a “side issue” I didn’t meant to imply that race itself is a side issue but that in the context of the story being told for children I didn’t see Alko obscuring race in her telling of the court incident. Interested to hear your opinion on the matter.

Identity matters and this is a hot topic not just in the field of race but in gender identity as well. And perhaps I’m not the best person to speak to the subject of race identity. If someone is multiracial but embraces only one race as their identity, is it incorrect then to mention the parts of their identity that they do not ascribe to in their personal life? What did Ms. Jeter say about how she was presented to the media and the courts? Clearly that’s what this all boils down to on some level. At the very least, the issue is complicated.

Good morning, Betsy, and thank you for what you’ve said in your response.

Here’s what uploaded at my site this morning in a post titled “Claiming, Misrepresenting, and Ignorance of Cherokee Identity.” In my next comment, I’ll respond to some points you raised (above) that are not addressed in my blog post.

Some books that we give to young children carry enormous weight. The Case for Loving: The Fight for Interracial Marriage is one example. It is about the Supreme Court’s decision in 1967, in which they ruled that people could marry whomever they loved, regardless of race.

Richard Loving was white. The woman he loved…. is misrepresented in The Case for Loving. The author, Selina Alko, echoed misrepresentations of who Jeter was when she wrote that Jeter was “part Cherokee.”

Jeter didn’t say that she was part Cherokee.

Indeed, her marriage license says “Indian” and when she elaborated elsewhere, she said Rappahannock. I wrote about this at length back in March of 2015.

Yesterday morning (July 2, 2015), I read Betsy Bird’s review of Alko’s book. This part brought me up short:

A side issue has arisen concerning Mildred’s identification as Native American and whether or not the original case made more of her African-American roots because it would build a stronger case in court. This is a far bigger issue than a picture book could hope to encompass, though I would be interested in a middle grade or young adult nonfiction book on the topic that went into the subject in a little more depth.

Actually, saying that it “brought me up short” doesn’t adequately describe what I felt.

First, I knew that Betsy was referencing my post. I took her use of “side issue” as being dismissive of me, and by extension, Arica Coleman (who I cite extensively), and by further extension, Native people who speak up about how we are represented–and misrepresented–in society, and in children’s books. On one hand, I felt angry at Betsy. As a teacher, though, I understand that we’re all on a continuum of knowing about subjects that are outside our particular realm of expertise.

Representation, and misrepresentation, of Native identity is important.

Because so many make that (fraudulent) claim, it strikes me as a significant wrong to see, in The Case of Loving, words that say Jeter was Cherokee when she did not say she was. It unwittingly casts her over in that land in which people claim an identity that is not really theirs to claim.

Here’s another reason that Betsy’s review (posted on July 2, 2015) bothered me. I read it within a specific moment in my work as a Native woman and scholar who is part of a Native community of scholars.

On July 30, 2015 (two days before Betsy’s review was posted), The Daily Beast ran a story about Andrea Smith, a key figure to many academics and activist who are committed to social justice, especially for women, and in particular, women of color. The focus of the article is Andrea Smith’s identity. For years, she claimed to be Cherokee. She said she was Cherokee. But, she wasn’t. She is amongst the millions of people who think that they have Cherokee ancestry. Some do, some don’t.

I met Andy several years ago (most people know her as Andy). At the time, she said she was Cherokee. I had no reason not to believe her. I don’t remember when I first heard that she might not be Cherokee, but I did learn (not sure when) that she had been asked by the Cherokee Nation to stop claiming that she is Cherokee. I don’t know what she personally did after that, and she has not said anything (to my knowledge) since the story appeared in The Daily Beast.

Things being said about Andy, about being Cherokee, and about claims to being Cherokee, reminded me of David Arnold’s Mosquitoland. There’s so much ignorance about being Cherokee! That ignorance was front and center in Arnold’s book. I’m deeply appreciative that he responded to my questions about it, and that he is talking with others about it, too. Those conversations are so important!

I view Andy’s failure to address her claim to Cherokee identity as a dismissal of the sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation. It is a dismissal of their nationhood and their right to determine who their citizens are. Andy knows what the stakes are for Native Nations, and for our sovereignty. She knows what she is doing.

Jeter was adamant about who she was. My guess is that she knew what the stakes were, for her personally, and for the Rappahannock who, as of this writing, are not yet federally recognized as a Native Nation.

Betsy doesn’t have the knowledge that Andy has. Few people do. Betsy is listening, though, as evidenced by her response to me this morning (see her comment on July 3). I am grateful to her for that response. She has far more readers than I do, and our conversation there will increase what people know, overall.

In that response, Betsy notes that Alko probably didn’t have the sources necessary to get it right. Let’s say ok to that suggestion, but, let’s also expect that the next printing of the book will get that part right, and let’s hope that editors in other publishing houses are talking to each other about this particular book and that they won’t be releasing books with that error.

That error may not matter to a non-Native child or her parents, but it matters to a Cherokee child and her parents. It matters to a Rappahannock child and her parents. It should matter to all of us, and it will (I say with optimism and perhaps naively, too), because we’re having these conversations.

By having them, I hope (again, optimistically and perhaps, naively), that we’ll move to a point in time when the majority of the American population will understands what it means to claim a Cherokee (or Native) identity, and a population that ceases to misrepresent Cherokee culture and history. In short, we’ll have a population that is no longer ignorant about Cherokee people specifically, and Native people, broadly speaking. Children’s books are part of getting us there. They carry a lot of weight.

For now, I’ll hit upload on this post, post the link in a comment to Betsy’s review, and respond (there) to other things Betsy said. I hope you’ll follow along there.

The other thing I wanted to comment on, Betsy, is the part about choosing a Native identity when ones identity is a combination of more than one.

For many reasons–including government boarding schools–Native people from a range of nations were in school together. Some fell in love and got married. Such was the case with me. My parents are from two different pueblos (Nambe, and, Ohkay Owingeh). If we look at biology, we’d say that I am a mix of two different groups. Which one am I? In my case, my mom went to Nambe, was subsequently listed on our tribal census, and as each one of us were born (I have 4 younger sibs), our names were added to the tribal census at Nambe. I say that I am tribally enrolled at Nambe. I’m not tribally enrolled at Ohkay Owingeh. I have lots and lots of cousins there, and I go there, but the nation I an enrolled with is Nambe.

My family lineage is not just Pueblo, though. Let’s say I took after (in appearance), my paternal grandfather. He was white, from Texas. If I looked like him, someone might look at me and speculate that I am racist against white people and in denial of my white American heritage. My answer? When I was a kid, I knew to say or write Nambe when asked to at school. I was proud of that identity as a cultural piece of who I was. As I grew older, I knew that my name on that tribal census meant more than just the cultural aspects of what it means to be raised there. It has a political aspect, too, that has to do with our status as a federally recognized sovereign nation. For a very long time, the Rappahannock’s have been trying to become one of the federally recognized tribal nations. My speculation about Jeter and her firm assertion that she was Rappahannock is rooted in my own experience. It doesn’t matter what you look like, or how mixed you might be in terms of biology. What you’re raised as, and your citizenship in that nation, is what matters culturally, but politically, too.

I think the Rappahannock may be on the cusp of being recognized. Just yesterday, news broke that another Virginia tribe, the Pamunkey, gained that status. Here’s one news story about it: http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/07/02/doi-issues-determination-pamunkey-becomes-no-567-first-federally-recognized-tribe-va

All that said, I will also note that Native peoples can be racist towards African Americans. Here’s a quote from the Washington Post story on Pamunkey recognition: “Members of Congress, including five Democratic congresswomen and members of the Congressional Black Caucus, had also opposed the Pamunkey bid, claiming that the tribe once had rules that discriminated based on race and gender. The tribe said it abandoned those practices long ago.” Arica Coleman discusses this in her book (cited in my initial post), THAT THE BLOOD STAY PURE.

Should any of this be in THE CASE FOR LOVING is a judgement call. I think some kids/families wouldn’t have trouble with it at all, and others would. I agree that we need more books about the Loving case, and as we’ve both said, we need a lot of conversations about all of this. There’s a lot to know.