new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Sir Edward Grey, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 8 of 8

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Sir Edward Grey in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: PennyF,

on 8/5/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

World,

world war I,

map,

month,

diplomacy,

gordon,

july,

first world war,

1914,

*Featured,

Images & Slideshows,

changed,

Archduke Franz Ferdinand,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

martel,

Gottlieb von Jagow,

Sir Edward Grey,

Raymond Poincaré,

Tsar Nicholas II,

Herbert Asquith,

Kaiser Wilhelm II,

King George V,

contributed,

Add a tag

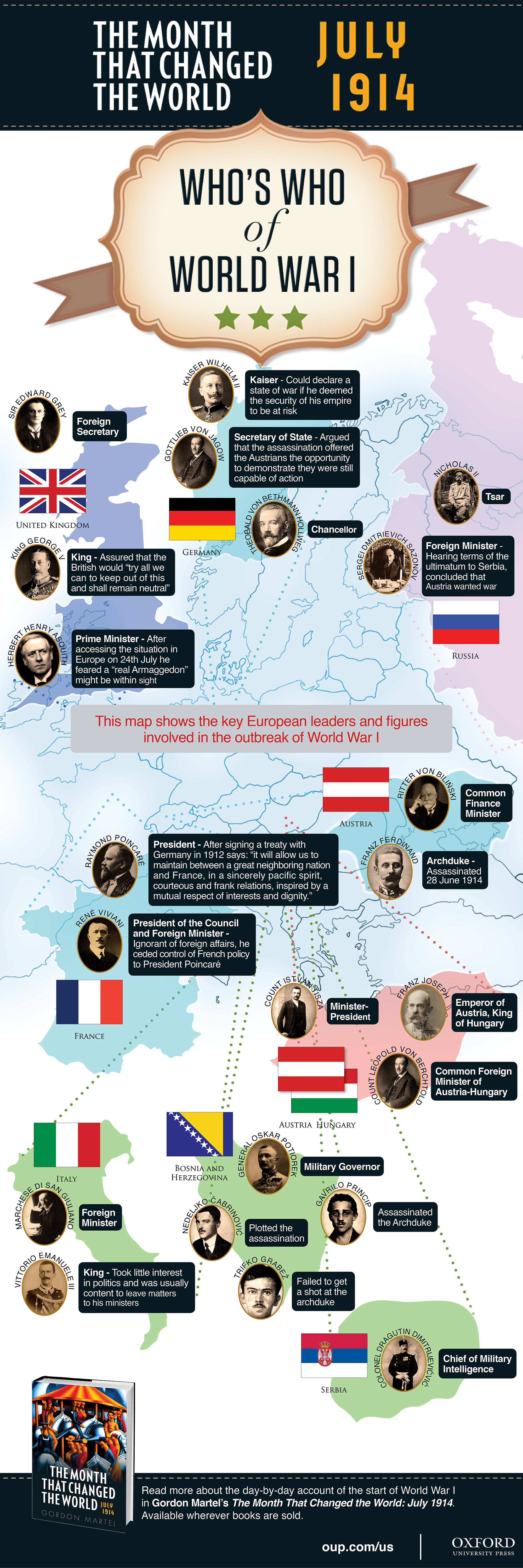

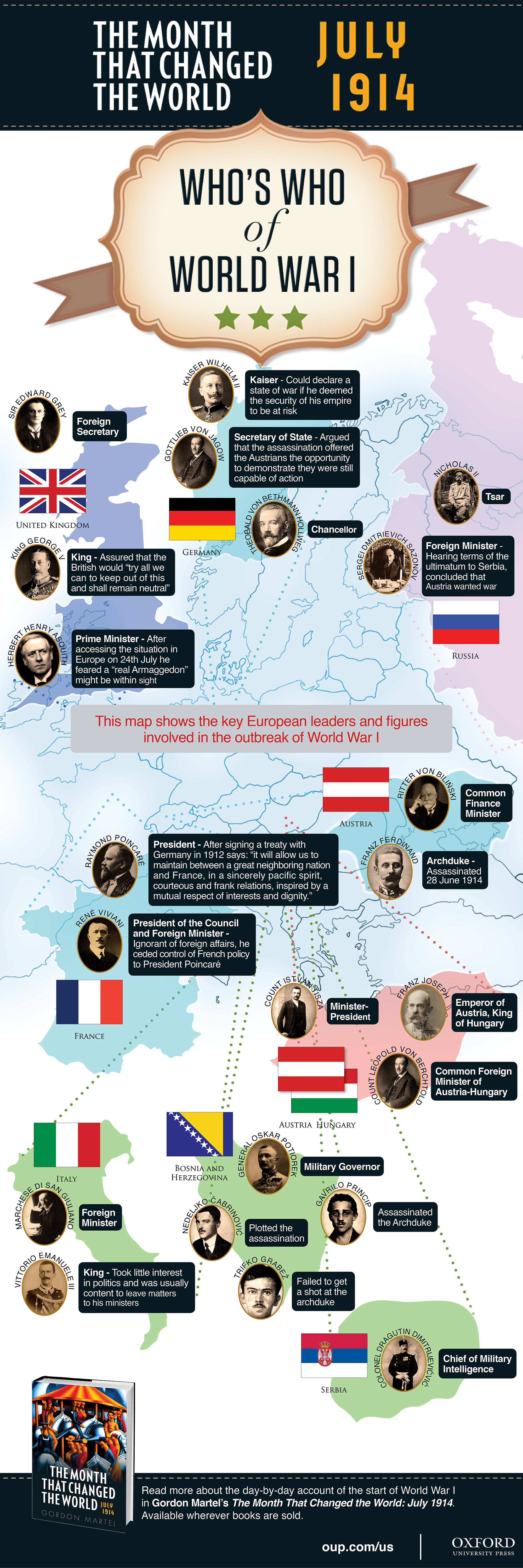

Over the last few weeks, historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us, giving a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events leading up to the First World War. July 1914 was the month that changed the world, but who were the people that contributed to that change? We wrap up the series with a Who’s Who of World War I below. Key countries have been highlighted with the corresponding figures and leaders that contributed to the outbreak of war.

Download a jpeg or PDF of the map.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Political map of Who’s Who in World War I [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 8/4/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

World,

Belgium,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

first world war,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

Sir Edward Grey,

august 1914,

British cabinet,

4 august 1914,

Belgian neutrality,

declaration of the first world war,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War. This is the final installment.

By Gordon Martel

At 6 a.m. in Brussels the Belgian government was informed that German troops would be entering Belgian territory. Later that morning the German minister assured them that Germany remained ready to offer them ‘the hand of a brother’ and to negotiate a modus vivendi. But the basis for any agreement must include the opening of the fortress of Liege to the passage of German troops and a Belgian promise not to destroy railways and bridges.

At the same time the British government was protesting against Germany’s intention to violate Belgian neutrality and requesting from the Belgian government ‘an assurance that the demand made upon Belgium will not be proceeded with, and that her neutrality will be respected by Germany’.

In Berlin they had already anticipated British objections. The German ambassador in London was instructed to ‘dispel any mistrust’ by repeating, positively and formally, that Germany would not, under any pretence, annex Belgian territory. He was to impress upon Sir Edward Grey the reasons for Germany’s decision: they had ‘absolutely unimpeachable’ information that France was planning to attack through Belgium. Germany thus had no choice but to violate Belgian neutrality because it was for them a matter ‘of life or death’.

The assurance was received in London at almost the same moment that the Foreign Office received news that German troops had begun their advance into Belgium.

Two of the four cabinet ministers who had threatened to resign now changed their minds: the news that the Germans had entered Belgium and announced that they would ‘push their way through by force of arms’ had simplified matters.

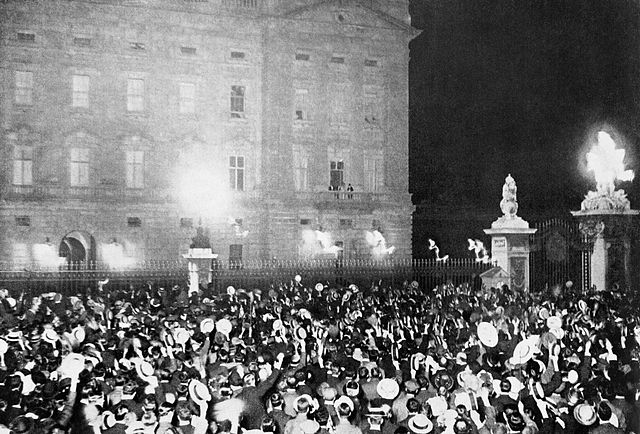

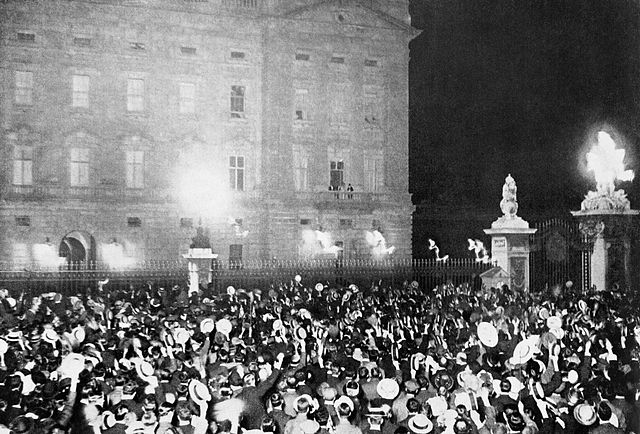

Crowds outside Buckingham Palace after war was declared. Imperial War Museums. IWM Non Commercial Licence via Wikimedia Commons.

At 10.30 a.m. Grey instructed the British minister in Brussels that Britain expected the Belgians to resist any German pressure to induce them to depart from their neutrality ‘by any means in their power’. The British government would support them in their resistance and was prepared to join France and Russia in immediately offering to the Belgian government ‘an alliance’ for the purpose of resisting the use of force by Germany against them, along with a guarantee to maintain Belgian independence and integrity in future years.

At 2 p.m. Grey instructed the ambassador in Berlin to repeat the request he had made last week and again this morning that the German government assure him that it would respect Belgian neutrality. A satisfactory reply was required by midnight, Central European time. If this were not received in time the ambassador was to request his passports and to tell the German government that ‘His Majesty’s Government feel bound to take all steps in their power to uphold the neutrality of Belgium and the observance of a Treaty to which Germany is as much a party as ourselves’.

Before the ambassador could present these demands, the German chancellor addressed the Reichstag, making a long, impassioned speech defending the government’s decision to go to war:

‘A terrible fate is breaking over Europe. For forty-four years, since the time we fought for and won the German Empire and our position in the world, we have lived in peace and protected the peace of Europe. During this time of peace we have become strong and powerful, arousing the envy of others. We have patiently faced the fact that, under the pretence that Germany was warlike, enmity was aroused against us in the East and the West, and chains were fashioned for us.’

A defence of German diplomacy during the crisis followed. Russia alone had failed to agree to ‘localize’ the crisis, to contain it to one that concerned only Austria and Serbia. Germany had warmly supported efforts to mediate the dispute and the Kaiser had engaged the Tsar in a personal correspondence to join him in resolving the differences between Russia and Austria. But Russia had chosen to mobilize all of her forces directed against Austria even though Austria had mobilized only against Serbia. And then Russia had chosen to mobilize all of her forces, leaving Germany with no choice but to mobilize as well.

France had evaded giving a clear answer to the question of whether it would remain neutral in the event of war between Russia and Germany. And then, in spite of promises to keep mobilized French forces 10 kilometres from the frontier with Germany ‘Aviators dropped bombs, and cavalry patrols and French infantry detachments appeared on the territory of the Empire!’

It was true that Germany’s decision to enter Belgium was a violation of international law, but there was no choice: ‘A French attack on our flank on the lower Rhine might have been disastrous’. And Germany would set right the wrong once ‘our military aims have been attained’.

‘We are fighting for the fruits of our works of peace, for the inheritance of a great past and for our future. The fifty years are not yet past during which Count Moltke said we should have to remain armed to defend the inheritance that we won in 1870. Now the great hour of trial has struck for our people. But with clear confidence we go forward to meet it. Our army is in the field, our navy is ready for battle–, and behind them stands the entire German nation– the entire German nation united to the last man.’

At almost the same moment Poincaré was addressing the French Chamber of Deputies. But indirectly, as the constitution prohibited the president from addressing the deputies directly. The minister of justice read his speech for him:

‘France has just been the object of a violent and premeditated attack, which is an insolent defiance of the law of nations. Before any declaration of war had been sent to us, even before the German Ambassador had asked for his passports, our territory has been violated.’….

‘Since the ultimatum of Austria opened a crisis which threatened the whole of Europe, France has persisted in following and in recommending on all sides a policy of prudence, wisdom, and moderation. To her there can be imputed no act, no movement, no word, which has not been peaceful and conciliatory.’….

‘In the war which is beginning, France will have Right on her side, the eternal power of which cannot with impunity be disregarded by nations any more than by individuals. She will be heroically defended by all her sons; nothing will break their sacred union before the enemy; today they are joined together as brothers in a common indignation against the aggressor, and in a common patriotic faith.’

‘Haut les coeurs et vive la France!’

At Buckingham palace at 10.45 the king had convened a meeting of the Privy Council for the purpose of authorizing the declaration of war. They waited for 11 p.m. to come, and when Big Ben struck they were at war. Meanwhile people had begun gathering outside the palace. When news began to spread throughout the crowd that war had been declared the excitement mounted; and when the king, the queen, and their eldest son appeared on the balcony ‘the cheering was terrific.’

By the end of the day five of the six Great Powers of Europe were at war, along with Serbia and Belgium. Diplomacy had failed. The tragedy had begun.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Tuesday, 4 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 8/3/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

World,

Belgium,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

belgian,

wwi,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

Sir Edward Grey,

Poincaré,

the july crisis,

declaration of war,

august 1914,

British cabinet,

coasts,

garitan,

brocqueville,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

At 7 a.m. Monday morning the reply of the Belgian government was handed to the German minister in Brussels. The German note had made ‘a deep and painful impression’ on the government. France had given them a formal declaration that it would not violate Belgian neutrality, and, if it were to do so, ‘the Belgian army would offer the most vigorous resistance to the invader’. Belgium had always been faithful to its international obligations and had left nothing undone ‘to maintain and enforce respect’ for its neutrality. The attack on Belgian independence which Germany was now threatening ‘constitutes a flagrant violation of international law’. No strategic interest could justify this. ‘The Belgian Government, if they were to accept the proposals submitted to them, would sacrifice the honour of the nation and betray at the same time their duties towards Europe.’

When the British cabinet reconvened later that morning at 11 a.m. there were now four ministers prepared to resign over the issue of British intervention. Their discussion lasted for three hours, at the end of which they agreed on the line to be taken by Sir Edward Grey when he addressed the House of Commons at 3 p.m. ‘The Cabinet was very moving. Most of us could hardly speak at all for emotion.’

Grey began his address to the House by explaining that the present crisis differed from that of Morocco in 1912. That had been a dispute which involved France primarily, to whom Britain had promised diplomatic support, and had done so publicly. The situation they faced now had originated as a dispute between Austria and Serbia – one in which France had become engaged because it was obligated by honour to do so as a result of its alliance with Russia. But this obligation did not apply to Britain. ‘We are not parties to the Franco-Russian Alliance. We do not even know the terms of that Alliance.’

But, because of their now-established friendship, the French had concentrated their fleet in the Mediterranean because they were secure in the knowledge that they need not fear for the safety of their northern and western coasts. Those coasts were now absolutely undefended. ‘My own feeling is that if a foreign fleet engaged in a war which France had not sought, and in which she had not been the aggressor, came down the English Channel and bombarded and battered the undefended coasts of France, we could not stand aside and see this going on practically within sight of our eyes, with our arms folded, looking on dispassionately, doing nothing!’ The government felt strongly that France was entitled to know ‘and to know at once!’ whether in the event of an attack on her coasts it could depend on British support. Thus, he had given the government’s assurance of support to the French ambassador yesterday.

There was another, more immediate consideration: what should Britain do in the event of a violation of Belgian neutrality? He warned the House that if Belgium’s independence were to go, that of Holland would follow. And what…

‘If France is beaten in a struggle of life and death, beaten to her knees, loses her position as a great Power, becomes subordinate to the will and power of one greater than herself’? If Britain chose to stand aside and ‘run away from those obligations of honour and interest as regards the Belgian Treaty, I doubt whether, whatever material force we might have at the end, it would be of very much value…’

‘I do not believe for a moment, that at the end of this war, even if we stood aside and remained aside, we should be in a position, a material position, to use our force decisively to undo what had happened in the course of the war, to prevent the whole of the West of Europe opposite to us—if that had been the result of the war—falling under the domination of a single Power, and I am quite sure that our moral position would be such as to have lost us all respect.’

While Grey was speaking in the House the king and queen were driving along the Mall to Buckingham Palace in an open carriage, cheered by large crowds. In Berlin the Russian ambassador was being attacked by a mob wielding sticks, while the German chancellor was sending instructions to the ambassador in Paris to inform the French government that Germany considered itself to now be ‘in a state of war’ with France. At 6 p.m. the declaration was handed in at Paris:

‘The German administrative and military authorities have established a certain number of flagrantly hostile acts committed on German territory by French military aviators. Several of these have openly violated the neutrality of Belgium by flying over the territory of that country; one has attempted to destroy buildings near Wesel; others have been seen in the district of the Eifel, one has thrown bombs on the railway near Karlsruhe and Nuremberg.’

The French president welcomed the declaration. It came as a relief, Poincaré said, given that war was by this time inevitable.

‘It is a hundred times better that we were not led to declare war ourselves, even on account of repeated violations of our frontier…. If we had been forced to declare war ourselves, the Russian alliance would have become a subject of controversy in France, national [élan?] would have been broken, and Italy may have been forced by the provisions of the Triple Alliance to take sides against us.’

When the British cabinet met again briefly in the evening they had before them the text of the German ultimatum to Belgium and the Belgian reply to it. They agreed to insist that the German government withdraw the ultimatum. After the meeting Grey told the French ambassador that if Germany refused ‘it will be war’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 3 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 8/2/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

World,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

first world war,

Lloyd George,

*Featured,

Luxembourg,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

Asquith,

Sir Edward Grey,

the july crisis,

Paul Cambon,

Treaty of London of 1867,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Confusion was still widespread on the morning of 2 August 1914. On Saturday Germany and France had joined Austria-Hungary and Russia in announcing their general mobilization; by 7 p.m. Germany appeared to be at war with Russia. Still, the only shots fired in anger consisted of the bombs that the Austrians continued to shower on Belgrade. Sir Edward Grey continued to hope that the German and French armies might agree on a standstill behind their frontiers while Russia and Austria proceeded to negotiate a settlement over Serbia. No one was certain what the British would do – especially not the British.

Shortly after dawn Sunday German troops crossed the frontier into the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Trains loaded with soldiers crossed the bridge at Wasserbillig and headed to the city of Luxembourg, the capital of the Grand-Duchy. By 8.30 a.m. German troops occupied the railway station in the city centre. Marie-Adélaïde, the grand duchess, protested directly to the kaiser, demanding an explanation and asking him to respect the country’s rights. The chancellor replied that Germany’s military measures should not be regarded as hostile, but only as steps to protect the railways under German management against an attack by the French; he promised full compensation for any damages suffered.

The neutrality of Luxembourg had been guaranteed by the Powers in the Treaty of London of 1867. The prime minister immediately protested the violation at Berlin, Paris, London, and Brussels. When Paul Cambon received the news in London at 7.42 a.m. he requested a meeting with Sir Edward Grey. The French ambassador brought with him a copy of the 1867 treaty – but Grey took the position that the treaty was a ‘collective instrument’, meaning that if Germany chose to violate it, Britain was released from any obligation to uphold it. Disgusted, Cambon declared that the word ‘honour’ might have ‘to be struck out of the British vocabulary’.

The cabinet was scheduled to meet at 10 Downing Street at 11 a.m. Before it convened Lloyd George held a small meeting of his own at the chancellor’s residence next door with five other members of cabinet. They were untroubled by the German invasion of Luxembourg and agreed that, as a group, they would oppose Britain’s entry into the war in Europe. They might reconsider under certain circumstances, however, ‘such as the invasion wholesale of Belgium’.

When they met the cabinet found it almost impossible to decide under what conditions Britain should intervene. Opinions ranged from opposition to intervention under any circumstances to immediate mobilization of the army in anticipation of despatching the British Expeditionary Force to France. Grey revealed his frustration with Germany and Austria-Hungary: they had chosen to play with the most vital interests of civilization and had declined the numerous attempts he had made to find a way out of the crisis. While appearing to negotiate they had continued their march ‘steadily to war’. But the views of the foreign secretary proved unacceptable to the majority of the cabinet. Asquith believed they were on the brink of a split.

After almost three hours of heated debate the cabinet finally agreed to authorize Grey to give the French a qualified assurance. The British government would not permit the Germans to make the English Channel the base for hostile operations against the French.

While the cabinet was meeting in the afternoon a great anti-war demonstration was beginning only a few hundred yards away in Trafalgar Square. Trade unions organized a series of processions, with thousands of workers marching to meet at Nelson’s column from St George’s circus, the East India Docks, Kentish Town, and Westminster Cathedral. Speeches began around 4 p.m. – by which time 10-15,000 had gathered to hear Keir Hardie and other labour leaders, socialists and peace activists. With rain pouring down, at 5 p.m. a resolution in favour of international peace and for solidarity among the workers of the world ‘to use their industrial and political power in order that the nations shall not be involved in the war’ was put to the crowd and deemed to have carried.

If the British cabinet was divided, so however were the people of London. When the crowd began singing ‘The Red Flag’ and the ‘Internationale’ they were matched by anti-socialists and pro-war demonstrators singing ‘God Save the King’ and ‘Rule Britannia’. When a red flag was hoisted, a Union Jack went up in reply. Part of the crowd broke away and marched a few hundred feet to Admiralty Arch where they listened to patriotic speeches. Several thousand marched up the Mall to Buckingham Palace, singing the national anthem and the Marseillaise. The King and the Queen appeared on the balcony to acknowledge the cheering crowd. Later that evening demonstrators gathered in front of the French embassy to show their support.

The anti-war sentiment, which was still strong among labour groups and socialist organizations in Britain, was rapidly dissipating in France. On Sunday morning the Socialist party announced its intention to defend France in the event of war. The newspaper of the syndicalist CGT declared ‘That the name of the old emperor Franz Joseph be cursed’; it denounced the kaiser ‘and the pangermanists’ as responsible for the war. In Germany three large trade unions did a deal with the government: in exchange for promising not to go on strike, the government promised not to ban them. In Russia, organized opposition to war practically disappeared.

Shortly before dinner that evening the British cabinet met once again to decide whether they were prepared to enter the war. The prime minister had received a promise from the leader of the Unionist opposition, Andrew Bonar Law, that his party would support Britain’s entry into the war. Now, if the anti-war sentiment in cabinet led to the resignation of Sir Edward Grey – and most likely of Asquith, Churchill and several others along with him – there loomed the likelihood of a coalition government being formed that would lead Britain into war anyway.

While the British cabinet were meeting in London they were unaware that the German minister at Brussels was presenting an ultimatum to the Belgian government at 7.00 p.m. The note contained in the envelope claimed that the German government had received reliable information that French forces were preparing to march through Belgian territory in order to attack Germany. Germany feared that Belgium would be unable to resist a French invasion. For the sake of Germany’s self-defence it was essential that it anticipate such an attack, which might necessitate German forces entering Belgian territory. Belgium was given until 7 a.m. the next morning – twelve hours – to respond.

Within the hour the prime minister took the German note to the king. They agreed that Belgium could not agree to the demands. The king called his council of ministers to the palace at 9 p.m. where they discussed the situation until midnight. The council agreed unanimously with the position taken by the king and the prime minister. They recessed for an hour, resuming their meeting at 1 a.m. to draft a reply.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Sunday, 2 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/31/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

World,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

Berchtold,

Sir Edward Grey,

René Viviani,

Bethmann Hollweg,

Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf,

Helmuth Johann Ludwig von Moltke,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Although Austria had declared war, begun the bombardment of Belgrade, and announced the mobilization of its army in the south, negotiations to reach a diplomatic solution continued. A peaceful outcome still seemed possible: a settlement might be negotiated directly between Austria and Russia in St Petersburg, or a conference of the four ‘disinterested’ Great Powers in either London or Berlin might mediate between Austria and Russia.

The German chancellor worried that if Sir Edward Grey succeeded in restraining Russia and France while Vienna declined to negotiate it would be disastrous; it would appear to everyone that the Austrians absolutely wanted a war. Germany would be drawn in, but Russia would be free of responsibility. ‘That would place us in an untenable situation in the eyes of our own people’. He instructed the ambassador in Vienna to advise Austria to accept Grey’s proposal.

In Vienna at 9 a.m. Berchtold convened a meeting of the common ministerial council, explaining that the Grey proposal for a conference à quatre was back on the agenda and that the German chancellor was insisting that this must be carefully considered. Bethmann Hollweg was arguing that Austria’s political prestige and military honour could be satisfied by the occupation of Belgrade and other points, while the humiliation of Serbia would weaken Russia’s position in the Balkans.

Berchtold warned that in such a conference France, Britain, and Italy were likely take Russia’s part and that Austria could not count on the support of the German ambassador in London. If everything that Austria had undertaken were to result in no more than a gain in ‘prestige’, its work would have been in vain. An occupation of Belgrade would be of no use; it was all a fraud. Russia would pose as the saviour of Serbia – which would remain intact – and in two or three years they could expect the Serbs to attack again in circumstances far less favourable to Austria. Thus, he proposed to respond courteously to the British offer while insisting on Austria’s conditions and avoiding a discussion of the merits of the case. The ministers agreed.

The British cabinet also met in the morning to consider France’s request for a promise of British intervention before Germany attacked. The cabinet divided into three factions: those who opposed intervention, those who were undecided, and those who wished to intervene. Only two ministers, Grey and Churchill, favoured intervention. Most agreed that public opinion in Britain would not support them going to war for the sake of France. But opinion might shift if Germany were to violate Belgian neutrality. Grey was instructed to request – from both Germany and France – an assurance that they would respect the neutrality of Belgium. They were not prepared to give France the promise of support that it had asked for; one of them concluded ‘that this Cabinet will not join in the war’.

Grey wired to Berlin to ask whether Germany might be willing to sound out Vienna, while he sounded out St Petersburg, on the possibility of agreeing to a revised formula that could lead to a conference. Perhaps the four disinterested Powers could offer to Austria to undertake to see that it would obtain ‘full satisfaction of her demands on Servia’ – provided that these did not impair Serbian sovereignty or the integrity of Serbian territory. Russia could then be informed by the four Powers that they would undertake to prevent Austrian demands from going to the length of impairing Serbian sovereignty and integrity. All Powers would then suspend further military operations or preparations.

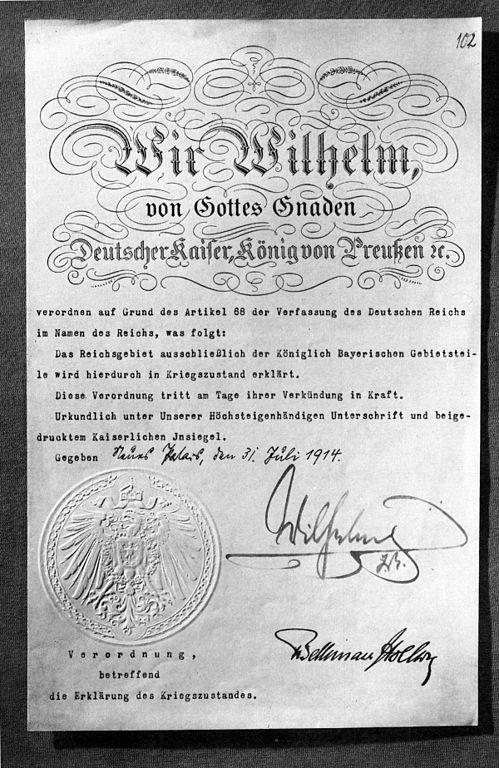

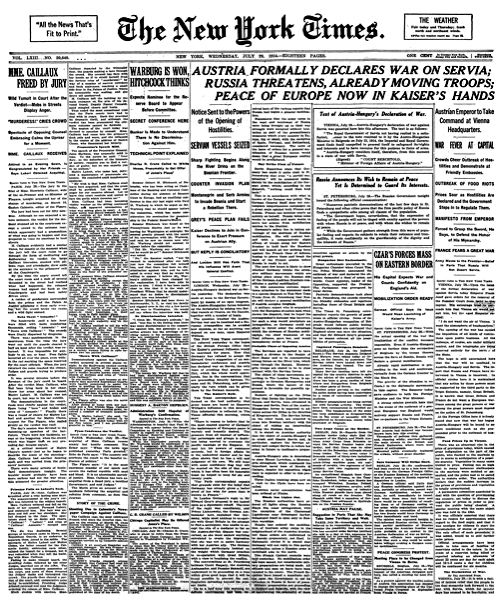

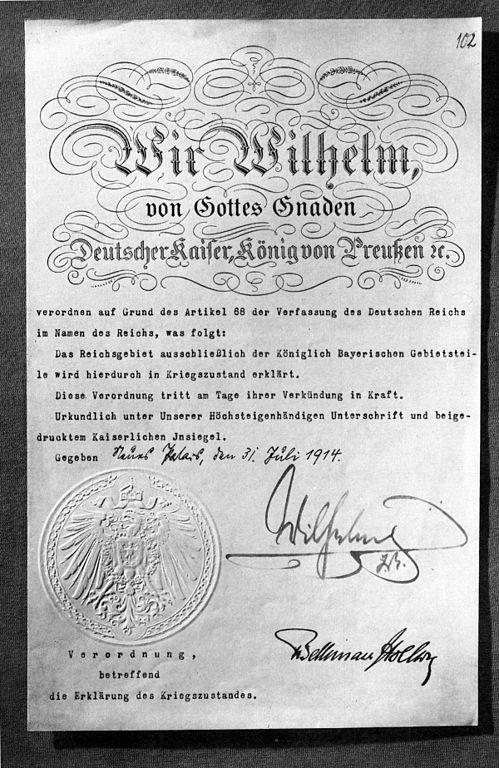

Declaration of war from the German Empire 31 July 1914. Signed by the German Kaiser Wilhelm II. Countersigned by the Reichs-Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Germany’s response was that it could not consider such a proposal until Russia agreed to cease its mobilization. In Berlin at 2 p.m. the the drohenden Kriegszustand (‘imminent peril of war’) was announced. At 3.30 p.m. Bethmann Hollweg instructed the ambassador in St Petersburg to explain that Germany had been compelled to take this step because of Russia’s mobilization. Germany would mobilize unless Russia agreed to suspend ‘every war measure’ aimed at Austria-Hungary and Germany within twelve hours. The time clock was to begin ticking from the moment that the note was presented in St Petersburg.

At 4.15 p.m. Conrad, the chief of the Austrian general staff, telephoned the office of the general staff in Berlin to explain the Austrian position: the emperor had authorized full mobilization only in response to Russia’s actions and only for the purpose of taking precautions against a Russian attack. Austria had no intention of declaring war against Russia. In other words, Russia could mobilize along the Austrian frontier and Austria could match this on the other side. And there the two forces could wait, without going to war.

This prospect terrified Moltke. He replied immediately that Germany would probably mobilize its forces on Sunday and then commence hostilities against Russia and France. Would Austria abandon Germany? Conrad asked if Germany thus intended to launch a war against Russia and France and whether he should rule out the possibility of fighting a war against Serbia without coming to grips with Russia at the same time. Moltke told him about the ultimatums being presented in St Petersburg and Paris, which required answers by 4 p.m. the next day.

At 6.30 p.m. the Kaiser addressed a crowd of thousands gathered at the pleasure gardens in front of the imperial palace. He declared that those who envied Germany had forced him to take measures to defend the Reich. He had been forced to take up the sword but had not ceased his efforts to maintain the peace. If he did not succeed ‘we shall with God’s help wield the sword in such a way that we can sheathe it with honour’.

In London and Paris they continued to hope that a negotiated settlement was possible. Grey suggested that Russia cease its military preparations in exchange for an undertaking from the other Powers that they would seek a way to give complete satisfaction to Austria without endangering the sovereignty or territorial integrity of Serbia. Viviani, the French premier and foreign minister, agreed. He would tell Sazonov that Grey’s formula furnished a useful basis for a discussion among the Powers who sought an honourable solution to the Austro-Serbian conflict and to avert the danger of war. The formula proposed ‘is calculated equally to give satisfaction to Russia and to Austria and to provide for Serbia an acceptable means of escaping from the present difficulty’.

In St. Petersburg that evening the German ambassador, in a private audience with Tsar Nicholas, warned that Russian military measures might already have produced ‘irreparable consequences’. It was entirely possible that the decision to mobilize when the kaiser was attempting to mediate the dispute might be regarded by him as offensive – and by the German people as provocative. ‘I begged him…to check or to revoke these measures’. The Tsar replied that, for technical reasons, it was not now possible to stop the mobilization. For the sake of European peace it was essential, he argued, that Germany influence, or put pressure on, Austria.

In Paris the German ambassador was to ask the French government if it intended to remain neutral in the event of a Russo-German war. An answer was required within 18 hours. In the unlikely case that France agreed to remain neutral, France was to hand over the fortresses of Verdun and Toul as a pledge of its neutrality. The deadline by which France must agree to this demand was set for 4 p.m. the next day

In St. Petersburg, at 11 p.m., the German ambassador presented the 12-hour ultimatum to Sazonov. If Russia did not abandon its mobilization by noon Saturday Germany would mobilize in response. And, as Bethmann Hollweg had already declared, ‘mobilization means war’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Friday, 31 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/30/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

Sir Edward Grey,

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg,

Sazonov,

Kaiser Wilhelm,

Joffre,

King George,

History,

World,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

world war I,

diplomatic solution,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

As the day began a diplomatic solution to the crisis appeared to be within sight at last. The German chancellor had insisted that Austria agree to negotiate directly with Russia. While Germany was prepared to fulfill the obligations of its alliance with Austria, it would decline ‘to be drawn wantonly into a world conflagration by Vienna’. Bethmann Hollweg was also promising to support Sir Edward Grey’s proposed conference to mediate the dispute. He told the Austrians that their political prestige and military honour could be satisfied by an occupation of Belgrade. They could enhance their status in the Balkans while strengthening themselves against the Russians through the humiliation of Serbia.

But a third initiative, the direct line of communication between the Kaiser and the Tsar, was running aground. Attempting to reassure Wilhelm, Nicholas explained that the military measures now being undertaken had been decided upon five days ago – and only as a defence against Austria’s preparations. ‘I hope from all my heart that these measures won’t in any way interfere with your part as mediator which I greatly value.’

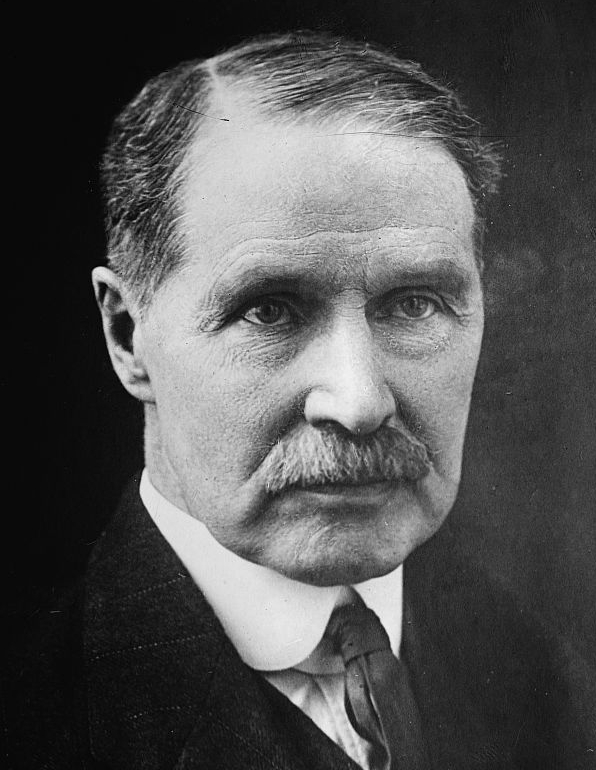

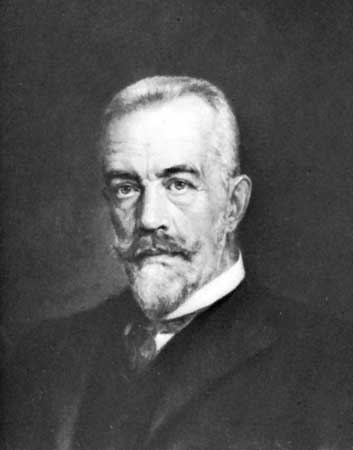

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, Chancellor of the German Empire, 1909-1917. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Wilhelm erupted. He was shocked to discover first thing on Thursday morning that the ‘military measures which have now come into force were decided five days ago’. He would no longer put any pressure on Austria: ‘I cannot agree to any more mediation’; the Tsar, while requesting mediation, ‘has at the same time secretly mobilized behind my back’.

The German ambassador in Vienna presented Bethmann’s directive to a ‘pale and silent’ Berchtold over breakfast. Austria, with guarantees of Serbia’s good behaviour in the future as part of the mediation proposal, could attain its aims ‘without unleashing a world war’. To refuse mediation completely ‘was out of the question’.

Berchtold did as he was told. He explained to the Russians that his apparent rejection of mediation talks was an unfortunate misunderstanding and that he was now prepared to discuss ‘amicably and confidentially’ all questions directly affecting their relations. He warned, however, that he would not yield on any of points in the note to Serbia.

At noon, Russia announced that it was initiating a partial mobilization. But the Austrian ambassador assured Vienna that this was a bluff: Sazonov dreaded war ‘as much as his Imperial Master’ and was attempting ‘to deprive us of the fruits of our Serbian campaign without going to Serbia’s aid if possible’.

In Berlin, the chief of the German general staff began to panic. A few hours after the Russian announcement he pleaded with the Austrians to mobilize fully against Russia and to announce this in a public proclamation. The only way to preserve Austria-Hungary was to endure a European war. ‘Germany is with you unconditionally’. Moltke promised that a German mobilization would immediately follow Austria’s.

In St. Petersburg the war minister and the chief of the general staff tried to persuade Nicholas over the telephone that partial mobilization was a mistake. The Tsar refused to budge. When Sazonov met with the Tsar at Peterhof at 3 p.m. he argued that general mobilization was essential; war was almost inevitable because the Germans were resolved to bring it about. They could easily have made the Austrians see reason if they had desired peace. The Tsar gave way. At 5 p.m. the official decree announcing general mobilization was issued.

In Paris the French cabinet was also deciding to take military steps. They agreed that – for the sake of public opinion – they must take care that ‘the Germans put themselves in the wrong’. They would try to avoid the appearance of mobilizing while consenting to at least some of the requests being made by the army. Covering troops could take up their positions along the German frontier from Luxembourg to the Vosges mountains, but were not to approach closer than 10 kilometres. No train transport was to be used, no reservists were to be called up, no horses or vehicles were to be requisitioned. Joffre, the chief of the general staff, was displeased. These measures would make it difficult to execute the offensive thrust of his war plan. Nevertheless, the orders went out at 4.55 p.m.

In London Grey bluntly rejected Bethmann’s neutrality proposal of the day before: ‘that we should bind ourselves to neutrality on such terms cannot for a moment be entertained’. Germany was asking Britain to stand by while French colonies were taken and France was beaten in exchange for Germany’s promise to refrain from taking French territory in Europe. Such a proposal was unacceptable ‘for France could be so crushed as to lose her position as a Great Power, and become subordinate to German policy’. On the other hand, if the current crisis passed and the peace of Europe preserved, Grey promised to endeavour to promote an arrangement by which Germany could be assured ‘that no hostile or aggressive policy would be pursued against her or her allies by France, Russia, and ourselves, jointly or separately’.

Shortly before midnight a telegram from King George arrived at Potsdam. Responding to an earlier telegram from the Kaiser’s brother, the King assured him that the British government was doing its utmost to persuade Russia and France to suspend further military preparations. This seemed possible ‘if Austria will consent to be satisfied with [the] occupation of Belgrade and neighbouring Servian territory as a hostage for [the] satisfactory settlement of her demands’. He urged the Kaiser to use his great influence at Vienna to induce Austria to accept this proposal and prove that Germany and Britain were working together to prevent a catastrophe.

The Kaiser ordered his brother to drive into Berlin immediately to inform Bethmann Hollweg of the news. Heinrich delivered the message to the chancellor at 1.15 a.m. and had returned to Potsdam by 2.20. Wilhelm planned to answer the King on Friday morning. The Kaiser noted, happily, that the suggestions made by the King were the same as those he had proposed to Vienna that evening.

Surely a peaceful resolution was at hand?

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Thursday, 30 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/29/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

World,

world war I,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

first world war,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

The Great War,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

Sir Edward Grey,

Kaiser Wilhelm,

Bethmann Hollweg,

Leopold Berchtold,

Sergey Sazonov,

Tsar Nicholas II,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Before the sun rose on Wednesday morning a new hope for a negotiated settlement of the crisis was initiated. The Kaiser, acting on the advice of his chancellor, wrote directly to the Tsar. He hoped that Nicholas would agree with him that they shared a common interest in punishing all of those ‘morally responsible’ for the dastardly murder of the Archduke, and he promised to exert his influence to induce Austria to deal directly with Russia in order to arrive at an understanding.

At 1 a.m. Nicholas appealed to Wilhelm for his assistance: ‘An ignoble war has been declared on a weak country.’ The indignation that this had caused in Russia was enormous and he anticipated that he would soon be overwhelmed by the pressure being brought to bear upon him, forcing him to take ‘extreme measures’ that would lead to war. To avoid this terrible calamity, he begged Wilhelm, in the name of their old friendship, ‘to do what you can to stop your allies from going too far.’

The question of the day on Wednesday was whether Austria-Hungary and Russia might undertake direct discussions to settle the crisis before further military steps turned a local Austro-Serbian war into a general European one.

The German general staff summarized its view of the situation: the crime of Sarajevo had led Austria to resort to extreme measures ‘in order to burn with a glowing iron a cancer that has constantly threatened to poison the body of Europe’. The quarrel would have been limited to Austria and Serbia had not Russia begun making military preparations. Now, if the Austrians advanced into Serbia, they would face not only the Serbian army but the vastly superior strength of Russia. Thus, they could not contemplate fighting Serbia without securing themselves against an attack by Russia. This would force them to mobilize the other half of their army – at which point a collision between Austria and Russia would become inevitable. This would force Germany to mobilize, which would lead Russia and France to do the same – ‘and the mutual butchery of the civilized nations of Europe would begin’.

In other words, unless a negotiated settlement could be reached quickly, war seemed inevitable.

Berchtold pleaded with Berlin that only ‘plain speech’ would restrain the Russians, i.e. only the threat of a German attack would stop them from taking military action against Austria. And there were signs that Russia was wary of war. The Austrian ambassador reported that Sazonov was desperate to avoid a conflict and was ‘clinging to straws in the hope of escaping from the present situation’. Sazonov promised that if they were to negotiate on the basis of Sir Edward Grey’s proposal, Austria’s legitimate demands would be recognized and fully satisfied.

At the same time, Sazonov was pleading for British support: the only way to prevent war now was for Britain to warn the Triple Alliance that it would join its entente partners if war were to break out.

But Grey refused to make any promises. When he met with the French ambassador later that afternoon, he warned him not to assume that Britain would again stand by France as it had in 1905. Then it had appeared that Germany was attempting to crush France; now, ‘the dispute between Austria and Serbia was not one in which we felt called to take a hand’. Earlier that day the British cabinet had decided not to decide; Grey was to inform both sides that Britain was unable to make any promises.

At 4 p.m. the German general staff received intelligence that Belgium was calling up reservists, raising the numbers of the Belgian army from 50,000 to 100,000, equipping its fortifications and reinforcing defences along the frontier. Forty minutes later a meeting at the Neue Palais in Potsdam, the Kaiser and his advisers decided to compose an ultimatum to present to Belgium: either agree to adopt an attitude of ‘benevolent neutrality’ towards Germany in a European war or face dire consequences.

Simultaneously, Bethmann Hollweg decided to launch a bold new initiative. He proposed to the British ambassador that Britain agree to remain neutral in the event of war in exchange for a German promise not to seize any French territory in Europe when it ended. He understood that Britain would not allow France to be crushed, but this was not Germany’s aim. When asked whether his proposal applied to French colonies as well, the chancellor replied that he was unable to give a similar undertaking concerning them. Belgium’s integrity would be respected when the war ended –as long as it had not sided against Germany.

Yet another German initiative was taken in St Petersburg. At 7 p.m. the German ambassador transmitted a warning from the chancellor that if Russia continued with its military preparations Germany would be compelled to mobilize, in which case it would take the offensive. Sazonov replied that this removed any doubts he may have had concerning the real cause of Austria’s intransigence.

The Russians found this confusing, as they had just received another telegram from the Kaiser containing a plea that he should not permit Russian military measures to jeopardize German efforts to promote a direct understanding between Russia and Austria. It was agreed that the Tsar should wire Berlin immediately to ask for an explanation of the apparent discrepancy. At 8.20 p.m. the wire asking for clarification was sent. Trusting in his cousin’s ‘wisdom and friendship’, Tsar Nicholas suggested that the ‘Austro-Serbian problem’ be handed over to the Hague conference.

A message announcing a general mobilization in Russia had been drafted and ready to be sent out by 9 p.m. Then, just minutes before it was to be sent out, a personal messenger from the Tsar arrived, instructing that it the general mobilization be cancelled and a partial one re-instituted. The Tsar wanted to hear how the Kaiser would respond to his latest telegram before proceeding. ‘Everything possible must be done to save the peace. I will not become responsible for a monstrous slaughter’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Wednesday, 29 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 7/6/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

military history,

World,

British,

This Day in History,

Europe,

wwi,

World War One,

first world war,

serbia,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

july crisis,

Berchtold,

Conrad von Hötzendorff,

Gottlieb von Jagow,

Sir Edward Grey,

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg,

Triple Alliance,

Add a tag

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Having assured the Austrians of his support on Sunday, the kaiser on Monday departed on his yacht, the Hohenzollern, for his annual summer cruise of the Baltic. When his chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, met with Count Hoyos and the Austrian ambassador in Berlin that afternoon, he confirmed that Germany would stand by them ‘shoulder-to-shoulder’. He agreed that Russia was attempting to form a ‘Balkan League’ which threatened the interests of the Triple Alliance. He promised to seize the initiative: he would begin negotiations to bring Bulgaria into the alliance and he would advise Romania to stop nationalist agitation there against Austria. He would leave it to the Austrians to decide how to proceed with Serbia, but they ‘may always be certain that Germany will remain at our side as a faithful friend and ally’.

In London the German ambassador, now back from a visit home, arranged to meet with the British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, on Monday afternoon. Prince Lichnowsky aimed to persuade Grey that Germany and Britain should co-operate to ‘localize’ the dispute between Austria and Serbia. Lichnowsky explained that the feeling was growing in Germany that it was better not to restrain Austria, to ‘let the trouble come now, rather than later’ and he reported that Grey understood Austria would have to adopt ‘severe measures’.

On Tuesday the Austrian government met in Vienna to determine precisely how far and how fast they were prepared to move against Serbia. The meeting went on for most of the day. The emperor did not attend; in fact, he left the city that morning to return to his hunting lodge, five hours away, where he would remain for the next three weeks. Berchtold, in the chair, told the assembled ministers that the moment had come to decide whether to render Serbia’s intrigues harmless forever. He assured them that Germany had promised its support in the event of any ‘warlike complications’.

The Triple Alliance

The ministers agreed that vigorous measures were needed. Only the Hungarian minister-president expressed any concern. Tisza insisted that they prepare the diplomatic ground before taking any military action, otherwise they would be discredited in the eyes of Europe. They should begin by presenting Serbia with a list of demands: if these were accepted they would have achieved a splendid diplomatic victory; if they were rejected, he would vote for war. Berchtold and the others disagreed: only by the exertion of force could the fundamental problem of the propaganda for a Greater Serbia emanating from Belgrade be eliminated. The argument went on for hours, but Tisza had the power of a virtual veto: Austria-Hungary could not go to war without his agreement. Reluctantly, the ministers agreed to formulate a set of demands to present to Serbia. These should be so stringent however as to make refusal ‘almost certain’.

On Wednesday, 8 July, officials at the Ballhausplatz began working on the draft of an ultimatum to be presented to Serbia. They were in no hurry. The chief of the general Staff, Conrad von Hötzendorff, had determined that, with so many conscript soldiers on leave to assist in the gathering of the harvest, it would be impossible to begin mobilization before 25 July. The ultimatum could not be presented until 22-23 July.

By Thursday in Berlin they were beginning to envision a diplomatic victory for the Triple Alliance. The secretary of state, Gottlieb von Jagow, just returned from his honeymoon, told the Italian ambassador that Austria could not afford to be submissive when confronted by a Serbia ‘sustained or driven on by the provocative support of Russia’. But he did not believe that ‘a really energetic and coherent action’ on their part would lead to a conflict. From London, Prince Lichnowsky reported that Sir Edward Grey had reassured him that he had made no secret agreements with France and Russia that entailed any obligations in the event of a European war. Rather, Britain wished to preserve the ‘absolutely free hand’ that would allow it to act according to its own judgement. Grey appeared confident, cheerful and ‘not pessimistic’ about the situation in the Balkans.

Meeting with the German ambassador in Vienna on Friday, Berchtold sketched some preliminary ideas of what the ultimatum to Serbia might consist of. Perhaps they might demand that an agency of the Austro-Hungarian government be established at Belgrade to monitor the machinations of the ‘Greater Serbia’ movement; perhaps they might insist that some nationalist organizations be dissolved; perhaps they could stipulate that certain army officers be dismissed. He wanted to be sure that the demands went so far that Serbia could not possibly accept them. What did they think in Berlin?

Berlin chose not to think anything. The ambassador was instructed to inform Berchtold that Germany could take no part in formulating the demands. Instead, he was advised to collect evidence that would show the Greater Serbia agitation in Belgrade threatened Austria’s existence.

At the same time the fourth – but secret – member of the Triple Alliance, Romania, was warning that it would not be able to meet its obligations to assist Austria. Romanians, the Hohenzollern king advised, were offended by Hungary’s treatment of its Romanian population: they now regarded Austria, not Russia, as their primary enemy. King Karl did not believe the Serbian government was involved in the assassination and complained that the Austrians seemed to have lost their heads. Berlin should exert its influence on Vienna to extinguish the ‘pusillanimous spirit’ there.

By the end of the week Italy had added its voice to the chorus of restraint. The foreign minister, the Marchese di San Giuliano, insisted that governments of democratic countries (such as Serbia) ‘could not be held accountable for the transgressions of the press’. The Austrians should not be unfair, and he was urging moderation on the Serbians. There seemed every reason to believe that peace would endure: the British ambassador in Vienna thought the government would hesitate to take a step that would produce ‘great international tension’, and the Serbian minister there had assured him that he had no reason to expect a ‘threatening communication’ from Austria.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Map highlighting the Triple Alliance. By Nydas. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post The month that changed the world: Monday, 6 July to Sunday, 12 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.