"I'm looking east," says the founder and CEO of Framestore.

The post ‘Gravity,’ ‘Dr. Strange’ VFX Studio Framestore Bought by Chinese Firm appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment

"I'm looking east," says the founder and CEO of Framestore.

The post ‘Gravity,’ ‘Dr. Strange’ VFX Studio Framestore Bought by Chinese Firm appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment

#28 The Golden Compass by Philip Pullman (1995)

#28 The Golden Compass by Philip Pullman (1995)

61 points

It’s refreshing when children’s literature tackles grand themes and trusts that the reader can handle them. Such is the case with Philip Pullman’s landmark 1995 fantasy. What’s more grand than a meditation on the human soul? But maybe Pullman’s greatest feat was to craft a story that is exceptional for all, full of bear kings, cowboy aeronauts, and animal “daemons”, it’s a mind-expanding trip. – Travis Jonker

Glorious. And what an ending — simply operatic. – Emily Myhr

For the first time I need to make a titular decision. Do I stay with the Yankee moniker “The Golden Compass” and list the book that way, or do I reach back to the book’s original British roots and call it “Northern Lights”, as was originally intended? Since I didn’t decide to list Pippi Longstocking as Boken Om Pippi Langstrump, I’ll continue to name the books here under their Americanized names. I am, after all, a Yankee.

The synopsis from the publisher reads, “The action follows 11-year-old protagonist Lyra Belacqua, accompanied by her daemon, from her home at Oxford University to the frozen wastes of the North, on a quest to save kidnapped children from the evil ‘Gobblers,’ who are using them as part of a sinister experiment. Lyra also must rescue her father from the Panserbjorne, a race of talking, armored, mercenary polar bears holding him captive. Joining Lyra are a vagabond troop of gyptians (gypsies), witches, an outcast bear, and a Texan in a hot air balloon.”

I may have come to the adult world of children’s literature thanks to Harry Potter, but it was Pullman who pulled me in the rest of the way. Living in Portland, Oregon shortly after graduating college (a lovely town to live in, but not ideal for the penniless post-student) I spent a lot of time in Powell’s Bookstore. One day I read an article in the paper that was accompanied by an image of a large cat boxing with Harry Potter and winning. The gist of the piece was that Harry was all well and good, but if you wanted some serious children’s literature you wanted to get your hands on the His Dark Materials books. That’s how they sold Pullman’s series at the start. Reviewers would contemptuously pooh-pooh the Harry Potter phenomenon in light of Pullman’s sophistication. You weren’t supposed to like them both. Many did. And in the coffee shop portion of Powell’s I devoured all three books and found them gripping, each and every one.

The term “embarrassment of riches” comes to mind when searching for information about this book. Particularly in terms of literary scholarship. So the question becomes less, “what is there to say?” and more “what should I not bother to say?” Let us begin at the very beginning then.

In a conversation with Leonard Marcus (found in the book The Wand in the Word: Conversations with Writers of Fantasy), Pullman describes the “lonely” process of writing the first two books, his dinner with Tolkien, and whether or not he had a plan in mind for the three books from the start. “Not a plan. But I knew what the story was going to be and where it was going to go and when it was going to end, and roughly how long it was going to be. I didn’t intend to write three books. I intended to write a long story. But it very quickly became evident that it would have to be published as three books because otherwise it would just sit on the shelves. It probably wouldn’t have gotten published. Who wou

This week is Banned Books Week, an annual event celebrating our freedom to read whatever we like. It’s not that we want to celebrate the banning of books, of course. What we celebrate is the power of books to convey ideas, even ideas that are shocking, controversial or unpopular.

This week is Banned Books Week, an annual event celebrating our freedom to read whatever we like. It’s not that we want to celebrate the banning of books, of course. What we celebrate is the power of books to convey ideas, even ideas that are shocking, controversial or unpopular.

Sponsored by the American Library Association and many others, Banned Books Week is an important way to shine a light on these books. Many of the books highlighted during Banned Books Week were only the target of attempted bans; a powerful reminder of the importance of staying vigilant about protecting our First Amendment right to read any books we like.

At First Book, we like to walk the walk, so we make a special effort to ensure that the schools and programs in our network have access to high-quality books – including many that have been banned, or the target of attempted bannings.

Check out these books (and more) on the First Book Marketplace, and make sure the kids you serve have the chance to read them all, and make up their own minds.

Is it Monday already? Where did the weekend go? Oh I know... taxes. hissssssss

I woke up this morning with a knot the size of Kansas in my back, which makes it pretty hard to do anything more than lay in bed and read all day. (Funny how your body forces you to take a day off once in a while, huh?)

Luckily a while back I stocked up on a few treats. Since I was up anyway making some Tater Tots (hey, its a "sick day", junk food is allowed) I thought I'd might as well blog about them (the treats, not the Tater Tots).

First up is Good Masters! Sweet Ladies!

This book is just charming!

Here's a nice little review of it, before it won the Newbery Medal.

And here is another nice article in the Medieval News blog about Ms. Schlitz and the book.

And Robert Byrd, the illustrator, has a cool slideshow of the books illustrations on his website.

I'd say that if you're into anything Medieval, or like plays, or would just like to read something refreshing, this is a good choice! I'm loving it.

My "read in bed at night" book right now is "The Golden Compass", which I'm aaaaaalmost finished with. I'm glad I bought the whole "His Dark Materials" trilogy so I can just dive right into the next one.

No, I haven't seen the movie. But I've seen enough trailers to have a hard time NOT picturing Nicole Kidman as I'm reading. Oh well.

This next book is more like "work", but its good:

I'd Rather Be in the Studio just says it all doesn't it?

This woman is good. She has a website. She just nails you on all the stuff you don't want to do to get yourself out there. I'm in kind of a "I need a makeover" mode right now and am looking for some guidance. Her advice is more for 'fine' artists than children's book illustrators, but its all good.

Just thought I'd share.

Well, the Tater Tots are done, my back is starting to scream at me from sitting in this chair, so I guess I'd better go. If I can get up...

Read the rest of this post

I've been a bad blogger this week, I know, I'm sorry.

I have some new art started, but I don't feel like showing it yet. Its all at that 'ugly stage', you know what I'm talking about.

I CAN tell you that the truffles in the picture are reference for some of what I'm working on. YUM. Who doesn't love a good truffle?

I wish I had something educational or insightful or... just plain interesting to talk about.

I've been reading some good blogs this week ~ the kind where people "learn you" something, or have something useful to share. I'm very impressed with that. I don't know how they do it AND do their art as well. A few:

The Extraordinary Pencil

Making a Mark

Maggie Stiefivater

I've started reading The Golden Compass, and am loving it. I want a daemon now. (No, I haven't seen the movie, didn't want to spoil the book.)

I promise I'll have some art to show this week, promise. Something. No more yarn ACEOs I don't think, I'm tired of doing those. But more yarn, yes, but just different. You'll see.

Here's how we play: first I pick a book. Then I pull a question card from my Table Topics cube and answer the question (the book gets chosen first so I don't cheat and choose an easy answer). Then, it's your turn. You pick a book and answer the question for your book in the comments. Though I will always choose a multicultural title, you certainly do not need to. Today's Book: Lowji Discovers America by Candace Fleming

Today's Book: Lowji Discovers America by Candace Fleming

Today' Question: Was the writing well-paced?

Yes, definitely! Especially with humorous books, the timing needs to be excellent to achieve true hilarity. I thought Candace Fleming did an excellent job in portraying Lowji as a truly funny, yet thoughtful, boy. Each short chapter in this easy middle reader forwards several aspects of the story at once: Lowji's adapting to a his new country (moving from Bombay, India to a small town in Illinois would cause anyone pause!), his summer boredom without any friends, his hope for a a pet, and the mystery of the five-toed footprints. Throw in a crotchety old neighbor, wonderful parents who understand the balance of Indian tradition with American culture, and a whole bunch of funny animals, and Fleming gets it just right.

Even on a sentence-by-sentence level, I love the pace of the humor.

"Landlady Crisp," I say.Lowji is such a cutie. And the book is more about being new, finding friends, and making the best of your situation (in his case, no pets!) than about being an immigrant. But Lowji's Indian culture, language, and way of thinking pervades the book without you noticing, making the book a wonderful combination of the two. Add a Comment

"Are you still here?" she asks. Her words snap like the firecrackers Bape and I light every Indian independence day. "What do you want?"

I take a deep breath. "A pet," I say. "A dog."

"No pets!" says Landlady Crisp. She scrubs the floor.

"A cat?" I say. "A cat would be nice."

"No pets!" she says. She scrubs harder.

I pause. I do not think I should ask for a horse, so instead I say, "A hamster? A gerbil? A teeny, tiny mouse?"

So we saw The Golden Compass tonight. Son and I had listened to the audiobook. Overall, I thought it was a good adaptation, but without giving away any spoilers, I found it curious where they decided to end the film vs. the book.

Obviously there's going to be a sequel, and I haven't listened to the second book yet (Son just got the Subtle Knife and the Amber Spyglass for Chanukah) so I can't comment on if it makes more sense to include a certain event in the first book in with the second movie rather than in the first.

But anyway, I'd be interested to hear what others think on this.

Unblogged books, in order of reading-- we have 2 left from October of 2006... (short and pithy, because I don't remember these books very well.)

As more and more Catholic school boards pull Phillip Pullman's The Golden Compass, Pearce Carefoote, author of Forbidden Fruit: Banned, Censored and Challenged Books from Dante to Harry Potter has been appearing on radio and television, speaking to the issue of censorship.

Hear the CBC radio podcast for November 26th, 2007 as Jian Ghomeshi interviews Carefoote on the topic of censorship.

The Toronto Star reports that Halton's Catholic board has pulled The Golden Compass from school library shelves, pending a review by its trustees. Author Philip Pullman, who describes himself as an atheist, apparently wrote the series His Dark Materials as a response to C. S. Lewis' Chronicles of Narnia (which ironically have been challenged themselves).

The Toronto Star reports that Halton's Catholic board has pulled The Golden Compass from school library shelves, pending a review by its trustees. Author Philip Pullman, who describes himself as an atheist, apparently wrote the series His Dark Materials as a response to C. S. Lewis' Chronicles of Narnia (which ironically have been challenged themselves).

Read a synopsis of The Golden Compass. It was voted the best children's book in the past 70 years by readers across the globe, according to news articles. Although it was published in 1995, the controversy is unfolding now because it has been made into a movie which will be released soon. Students can ask librarians for the book but it will not be displayed on shelves.

Toronto Star readers have voiced their opinions, many coming out in support of the presence of the book in schools.

Everynight Life

Celeste Frazier Delgado, Jose Esteban Muñoz (eds.)

This book explores the varied tradition of dance throughout Latino/a America: salsa, merengue, rumba, mambo, tango, samba and norteña as a language of resistance. The editors reveal the history of these popular forms of dance as syncretic practices of African, indigenous, and mestizo people in the Americas. Much in the same way popular forms of African-American dance preserved traditional values of an oppressed people, so did the people’s of Latino/a America survive a dominant culture of of liquidation and negation. The most striking example of this is the Brazilian example, capoeira. It is both a syncretic dance practice of Yoruba devotees and a martial art. Slaves and former slaves developed capoeira as a means to resist and defend themselves. To a lesser extent, dance forms as popular as salsa, merengue, etc. reflect ancient tribal forms which celebrate the earth and body, resisting co-optation by European invaders. In fact, these dances insinuated themselves into mainstream culture and became popular themselves. They represent a kind of subversion to a Eurocentric idea of body, personal space and identity. I was fascinated by the editors’ premise that dance uses the body and its movement as a language, a code. I was reminded of the possibility to invent story by movement, by the symbolism of moving flesh.

ISBN-10: 0822319195

ISBN-13: 978-0822319191

Riverbed of Memory

Daisy Zamora

Daisy Zamora was a member of Nicaragua’s Sandinista Liberation Army. She was program director of the clandestine Radio Sandino during the revolution, and later became a Vice Minister of Culture in the revolutionary government. In Riverbed of Memory, Zamora writes poetry about the horrors of war, its causes and its aftermath. What is stunning about the book is its elliptical, subtle portrayal of its subject matter. She creates a riveting portrayal of violence and death, by inference, and it is all the more powerful because of it. I was spellbound by a writer who could capture the essence of something horrible without cliche, without beating the reader to a bloody pulp. Zamora accomplishes this with economy and simplicity. In a particularly strong piece, Zamora compares the spilled blood of a child to the first fruit of the harvest, crushed under the boot of a soldier, its pulp staining the earth. I found in Riverbed of Memory examples of how to write about strongly charged material indirectly, helping the reader to understand the enormity of catastrophe by describing the shadow it casts.

ISBN-10: 0872862739

ISBN-13: 978-0872862739

Gringa Latina: A Woman of Two Worlds

Gabriella De Ferrari

Gabriella De Ferrari is a curator, lecturer and Peruvian expatriate living in New York City. Gringa Latina is the story of her journey between two worlds. She describes in loving detail her life in a small rural town where her father was a doctor. The reader follows De Ferrari through her home town, along its riverbank, its grove of olive trees, the sights and sounds of her mother’s kitchen. With similar detail, she describes her culture shock at the crowds of people in New York, her first subway ride, her first nervous attempts to mount and promote an exhibit. While clearly De Ferrari’s affluence protected her from the worst aspect of being a stranger in a strange land, she captures the emigre’s sense of loneliness, loss and anomie. Her language is clean and spare, and I found this book helpful in thinking about the creation of memoir as a whole, and my piece in particular. Gringa Latina uses the very personal account of one woman’s journey to tell a larger human story through the use of the particular, connection to place, and the recreation of home.

ISBN-10: 1568361459

ISBN-13: 978-1568361451

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Presented by

CHICAGO FOUNDATION FOR WOMEN'S Latina Leadership Council

6:30 p.m. wine and cheese reception

8-9:30 p.m. performance

Friday, Nov. 9

Chicago Dramatists

1105 W. Chicago Ave.

Chicago

Call (312) 577-2801 ext. 229. Tickets are $45.

Proceeds from this event benefit the Unidas Fund of the Latina Leadership Council. No refunds or exchanges.A world premiere production, "MACHOS" is an interview-based play about contemporary masculinities. As always, Teatro Luna asks hard-hitting questions, such as: Exactly how did you learn to use the urinal? "MACHOS" presents a range of true-life stories with Teatro Luna’s trademark humor and unique Latina point-of-view.

"MACHOS" follows Teatro Luna's critically-acclaimed shows "S-E-X-OH" and "LUNATIC(A)S." It moves beyond the everyday stereotypes of gender, offering a complex look at how 50 men (and eight Latina women) learned how to be men. Performances

are drawn from interviews with 50 men nationwide and performed by an all-Latina cast in drag. After the performance there will be a reception with director Coya Paz and the actors.

Featuring Belinda Cervantes, Maritza Cervantes, Yadira Correa, Gina Cornejo, Ilana Faust,

Stephanie Gentry-Fernandez and Wendy Vargas.

Learn more about the Latina Leadership Council of Chicago Foundation for Women

Chicago Dramatists is wheelchair-accessible.

If you have other accesibility needs or questions, please contact Marisol Ybarra by Nov. 6 at (312) 577-2836 / TTY (312) 577-2803 or [email protected].

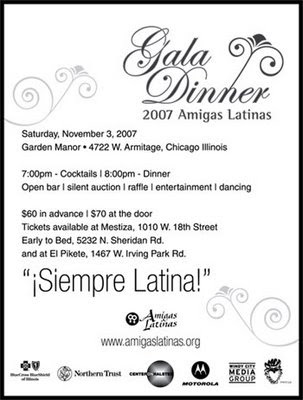

SAVE THE DATE

November 3, Saturday

¡Siempre Latina!

Gala Dinner

Garden Manor

4722 W. Armitage

Chicago, IL

Tickets:

$60 advance

$70 at door

Available: Mestiza 1010 W. 18 Street Chicago, IL 312 563 0132

Early to Bed

5232 N. Sheridan Rd. Chicago, IL

773 271 1219

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

AND MORE ABOUT MARGO TAMEZ

THE OTHER VOICES WOMEN’S READING SERIES PRESENTS MARGO TAMEZ

MARGO TAMEZ is the recipient of a Poetry Fellowship from the Arizona Commission on the Arts and a First Place Literary Award from the Frontera Literary Review. She is the author of Naked Wanting, also published by the University of Arizona Press. She is of Jumano and Lipan Apache as well as Spanish Land Grant ancestry of South Texas and currently lives in Pullman, Washington.

Friday, November 9th at 7:00 p.m.

Antigone Books,

411 North 4th Avenue

520-792-3715

RAVEN EYE Written from thirteen years of journals, psychic and earthly,

this poetry maps an uprising of a borderland

indigenous woman battling forces of racism

and sexual violence against Native women and children.

This lyric collection breaks new ground, skillfully

revealing an unseen narrative of resistance on the

Mexico–U.S. border. A powerful blend of the oral

and long poem, and speaking into the realm of global

movements, these poems explore environmental injustice,

sexualized violence, and indigenous women’s lives.

These complex and necessary themes are at the

heart of award-winning poet Margo Tamez’s second

book of poetry. NAKED WANTING Speaking with the voice of the cicada and the cricket,

the raven and the crane, Margo Tamez shows us that

the earth is a vibrant network of birth, death, and rebirth—

a sacred intertwining from which we as humans have

become disconnected. Through images that remind us

of Nature’s beauty and fragility, reflections on childbirth

and children, and warnings of environmental abuse,

she brings to her poetry the insight of someone

who has experienced firsthand what happens

when our land and water are compromised.

“Margo Tamez’s poetry works like a heartsong,

it makes us brave. Her alive response to what kills

makes us want to stand up with her and sing in

the face of the enemy. . . . They say that women

at war pose the most serious threat, and so it is

that Margo Tamez’s call to battle both instills

fear and thrills us.” —Heid E. Erdrich

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Welcome to the first ever Book Question of the Week Game! Here's how we play: first I pick a book. Then I pull a question card from my Table Topics cube and answer the question (the book gets chosen first so I don't cheat and choose an easy answer). Then, it's your turn. You pick a book and answer the question for your book in the comments. Though I will always choose a multicultural title, you certainly do not need to. Today's Book: The Arrival by Shaun Tan

Today's Book: The Arrival by Shaun Tan

Today's Question: How could the conflict have resolved differently?

There isn't so much a conflict in The Arrival as there is a situation. Or maybe it's just that the situation, rather than characters, provides the conflict. So the situation could certainly have turned out differently.

The Arrival is a wordless book, or graphic novel (are they different?), in which the foreign arriver is not the little creature on the cover, but the man who is studying him. This is an immigration story set in a fantasy world-- an incredibly beautiful, majestic, full, and foreign fantasy world. It was also the first time that I truly understood what it was like to be an immigrant while reading a book. Because the man's new home is like nothing here on earth, I felt like a new arrival myself. I couldn't read the signs, and I didn't understand the culture. At the same time, Tan used his amazing wordless pictures to convey how much the man missed his family back home.

The book ultimately has a happy ending, like many real-life immigrant stories. I think that people are extremely adaptable, and there is no doubt that with time, this man would settle in and feel comfortable in this strange new world. In real life, however, the story of his wife and daughter may not have resolved so wonderfully as it did in this book. There are so many families that are not able to join the members that first moved to another country.

The ending of The Arrival was the best possible one for this immigrant and his family (and made me cry); it certainly could have turned out much worse.

Now, it's your turn! Write an answer for a book of your choice in the comments.

One last post before I go-go...

Also, can I say how much I am NOT looking forward to flying with the double whammy ear and sinus infection combo? The Beijing Kao Ya, however, should make up for it. (That's Peking Duck. I've been brushing up on my food vocabulary.)

Also, 'cuz I'll be offline, an early Shana Tovah to y'all. I'm celebrating by climbing a Taoist mountain (Tai Shan) to watch the sunrise. I figure starting the Days of Awe with a bit of awe is probably a good thing.

Anyway, one last book review.

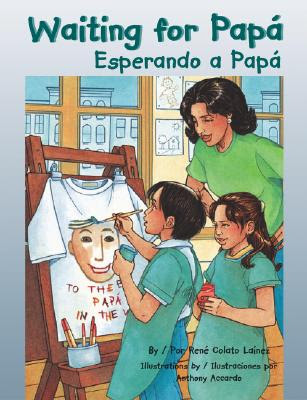

René Colato Laínez

This is the last part of Living To Tell the Story: The Authentic Latino Immigrant Experience in Picture Books. This was my critical thesis for my MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults at Vermont College. Living To Tell the Story won an honorable award during my last semester at Vermont College.

My Immigrant Experience

I have followed and kept close to my heart Juan Felipe Herrera’s message “Always believe in yourself; don’t forget where you come from and don’t be afraid of life”. El Salvador is my country of origin, Spanish is my native tongue, and I do not give up. I am an immigrant and have experienced the stages of uprooting myself. I have lived to tell the story.

I was born in El Salvador. As a child, I went to school, recited poetry, played with my friends and won a hula-hoop contest on national television. I had a dream to become a teacher.

When I was around ten years old, the water stopped running in our house and the electricity was cut off. The silent nights became very loud. Bombs destroyed factories and homes. Many innocent people died during shootings everywhere in the country. In the mornings when I walked to school, soldiers marched down the streets with big rifles. I saw more dead bodies than pebbles on the sidewalks. When I was fourteen armies of masked men broke into schools and recruited all the students. I did not even want to go to school or anywhere. I had constant nightmares about being caught and becoming the next victim.

The world turned upside down when my father and I fled to the United States. I was uprooted by necessity from my beloved country, relatives and friends. Without being prepared, I encountered the first stage of uprooting, mixed emotions. Luckily my mother had come a year earlier. She had a job for my father and a house where we felt secure.

The second stage of uprooting, excitement and fear in the adventure of the journey was unforgettable. On my long and tiring trip, we sneaked across three borders. I became an illegal immigrant in three countries. At the Mexican/ Guatemalan border, a Mexican Immigration Border Patrol took all my father’s money. We were allowed to cross the border in exchange for our money. In Mexico City, my father and I became homeless. An old trailer became our home for two months. During this time, my mother collected more money for our trip. Then, my nightmare began. I had to cross the American border illegally. For two days, I walked, ran and climbed big mountains without food or water. The brand new shoes that Mamá sent me for Christmas were all torn up and without soles. I reached the United States practically without shoes at all. In a park, my mother gave a packet of money to the coyote who brought us. Then we hugged each other. A few hours later, my mother bought me a new pair of shoes.

Soon, I was in my third stage of uprooting, curiosity. I was thrilled when I saw a color television in our new apartment. In El Salvador, my family had a small black and white television. Now, I had a big screen color television all to myself.

In June, I started ninth grade at Milikan Junior School. It was chaos, a very different world from home. I was in my fourth stage of uprooting, culture shock that exhibits as depression and confusion. I did not understand my teachers; children ran from one classroom to another; the books were filled with letters that I knew but words that did not make sense to me. For the first time in my student life, I hated school.

Within three months, I was a high school student. I studied hard and did my best at school but for me it was not enough. During my silent period, all the teachers spoke English. I had so many things to tell them but I did not know how. Mrs. Allen was the only teacher who spoke Spanish. In her class, I felt secure and began to participate. Mrs. Allen was the first teacher who believed in me. Thanks to her affection, I broke out of my silent shell and I started getting good grades at school in all the subjects. In my fifth stage of uprooting assimilation/ acculturation into the mainstream, I acculturated to school and my surroundings.

Years later, I graduated with honors from high school. Then, I studied at California State University, Northridge and received a Bachelor Degree in Liberal Studies. Eight years after leaving El Salvador, I accomplished my dream of becoming a teacher.

Now, I have accomplished another dream. I am an author. My first two picture books Waiting for Papá/ Esperando a Papá and I Am René, the Boy/ Yo soy René, el niño are based on my immigrant experience. Reading and analyzing the works of authors like Amada Irma Pérez, Jorge Argueta, Jane Medina and Juan Felipe Herrera have helped me write more genuine and authentic manuscripts.

My goal as a writer is to write good multicultural children’s literature. Stories where minority children are represented in a good positive way. Stories where they can see themselves as heroes. Stories where children can dream and have hopes for the future. I want to show readers authentic stories of Latin American children living in the United States.

René Colato Laínez

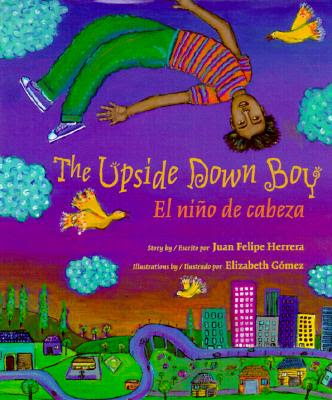

The Upside Down Boy/ El niño de cabeza is Juan Felipe Herrera's memoir of the year his migrant family moved to the city so that he could go to school for the first time. Neither of his parents had the opportunity to complete school, but valued the importance of education. Juanito is not an immigrant himself but his parents are. However, he has grown up singing and speaking Spanish with his parents, friends and neighbors. When he comes to school, he enters into a different strange world.

Just as other immigrant children do, he experiences the fourth stage of uprooting, culture shock that exhibits as depression or confusion. Juan Felipe Herrera writes:

“Don’t worry, chico," Papi says as he walks me to school.

I pinch my ear. Am I really here?

Maybe the street lamp is really a golden cornstalk with a dusty gray coat.

People speed by alone in their fancy melting cars. In the valleys, campesinos sang “Buenos dias, Juanito.”

I make a clown face, half funny, half scared. “I don’t speak English,” I say to Papi.

“Will my tongue turn into a rock?”

When immigrant children enter school for the first time, they have so many questions running through their heads and no answers at all. And if teachers answer their questions, immigrant children do not understand them because they are in English. Every time that I wanted to speak in English, I felt that my tongue stuck to my teeth. I could not produce a sound. I felt paralyzed.

When Juanito comes to his classroom, he is terrified. School was not what he had expected. The room looks so strange. It feels like everyone is staring at him. Juanito enters into the silent period:

¿Donde estoy? Where am I?

My question in Spanish fades as the thick door slams behind me.

Mrs. Sampson, the teacher, shows me my desk. Kids laugh when I poke my nose into my lunch bag. The hard round clock above my head clicks and aims its strange arrows at me.

“What is your name?” Mrs. Sampson asks.

My tongue is a rock.

This is the first interaction between Juanito and his teacher. When the teacher asked for his name, Juanito does not have a clue of what she is saying. He knows that he has to say something but he is not able to do it. This is a common experience for immigrant children. My first day at school, a counselor who spoke a few words of Spanish went over my classes for the semester. She spoke very slowly in English and asked me in Spanish, “Comprende?” (Do you understand?) I nodded the whole time, but I did not know what she was talking about.

During recess time Juanito does not know what to do. He sits down and eats his potato burrito while everyone else plays. He feels so strange. Juanito often does the wrong thing during times designated for other activities.

The high bell roars again. This time everyone eats their sandwiches while I play in the breezy baseball diamond by myself.

When I jump up everyone sits.

When I sit all the kids swing through the air.

My feet float through the clouds when all I want is to touch the earth.

I am the upside down boy.

Immigrant children can vividly relate to this experience. When they enter school they feel frightened, shy, and "de cabeza," upside down, like an alien in another planet.

In Junior High school in El Salvador, students stayed in their own classroom and teachers moved from classroom to classroom. At my new American school, I sat down in the classroom while everyone left. I waited for my next teacher and he never came. “You have to go to another classroom,” a boy said in Spanish.

Fortunately, Juanito has a teacher like Jane Medina. Mrs. Sampson is very understanding with him. She became the light at the end of the tunnel.

Mrs. Sampson invites me to the front of the class.

“Sing Juanito, sing the song we have been practicing.”

I pop up shaking. I am alone facing the class.

“Ready to sing?” Mrs. Sampson asks me.

“Three blind mice, three blind mice,” I sing.

My eyes open as big as the ceiling and my hands spread out as if catching rain drops from the sky.

“You have a very beautiful voice, Juanito,” Mrs. Sampson says.

“What is beautiful?” I ask Amanda after school.

Mrs. Sampson is the one who helps Juanito to leave the fourth stage of uprooting and enter the final stage, assimilation and acculturation into the mainstream. Mrs. Sampson helps him find his voice through poetry, art, and music. With her encouragement and the support of his family, Juanito not only fits in, but shines. Mrs. Sampson is the teacher, the human being, the hope that every immigrant child desperately needs to feel useful in the classroom.

At the end of the story, Juanito feels fine at school. He is drawing, painting, singing and speaking. Juanito overcomes his fears in school despite the challenge of adapting to an unfamiliar language and culture. Juan Felipe is so grateful to his teacher that he dedicates this book to her.

For Mrs. Lucille Sampson, my third grade teacher at Lowell Elementary School, Barrio of Logan Heights, San Diego, California, 1958, who first inspired me to be a singer of words, and most of all, a believer in my own voice. Gracias. Thank you.

Mrs. Sampson had touched the future and filled Juan Felipe Herrera’s life with hope. After this experience, Herrera felt liberated and did very good at school. Now he is a poet, a writer and a creative writing teacher.

Juan Felipe Herrera uses his own experiences in third grade and gives a

message of hope to immigrant children. While Herrera was born in the United States to a family of Mexican immigrants, his native language was Spanish, and he grew up in a house with Mexican stories and immigrant relatives arriving from Mexico. Therefore, he can relate to the immigrant experience. In an e-mail interview, he said:

I was pretty insulated-- living on the outskirts of cities, in small, tiny towns, mountains, rancho and lake communities. When I did enter school, the big shock did come -- however it was a muted shock; how do you talk about it, what is it that is happening; it's like losing your voice when you are thrown into an opera on your life. My imagination flourished; I became a passionate observer and dreamer, I created a parallel universe.

Juan Felipe Herrera believes that Latino Children need more stories about their lives in the United States. He wants to see more new Latino authors writing for their own communities.

In order to write an authentic story, you need honesty at all levels, real words from real people and incidents, crises and transformation,suffering and joy. The book must have a kind mind and a warm giant heart.

As a creative writing teacher, Herrera’s goal is to awaken students' appreciation for their own voice, cultural life, and personal expression. He wants to pass on the encouragement and help that Mrs. Sampson transmitted to him when he was a child. His message for immigrant children is, “Always believe in yourself; don’t forget where you come from and don’t be afraid of life.”

René Colato Laínez

My Name is Jorge On Both Sides of the river is a collection of 27 poems in English and Spanish about another Jorge’s immigrant experience in the United States.

Jane Medina starts with the second stage of uprooting, excitement and fear in the adventure of the journey. Every time that Jorge crosses the busy street to go to school, he always remembers the time when he crossed the river. Jane Medina reveals Jorge’s fears during this odyssey in the poem The Busy Street.

I’m holding Mimi’s hand very tight, again

as tight as I held it

When we crossed the river to come here.

I was so afraid.

Mimi and I had to cross first.

while my mamá and my papá waited

on dry, Mexican sand.

Mamá stands under the stop light

making us go first again.

She is pushing the air toward school with one hand.

She is telling us to go fast

-fast across the busy street.

At least we crossed the river only once.

We have to cross this street every day.

Many immigrant children can relate to this poem. Unfortunately, the majority of immigrant children must cross the Rio Grande or big mountains to come to the United States. Children who are not immigrants can read about the hard experience that immigrant children go through in order to be in America and understand them a little better. For immigrant children this experience is always fresh in their minds. It changes their lives. It is an unforgettable experience. Jane Medina concentrates on the fourth stage of uprooting, the culture shock that exhibits as depression and confusion. Jorge’s first culture shock is with his name. Jorge loves his name. But at school the teacher calls him George.

My name is Jorge.

I know that my name is Jorge.

But everyone calls me

George.

George.

What an ugly sound!

Like a sneeze!”

GEORGE!”

And the worst of all

is thatthis morning

a girl called me

“George”

and I turned my head.

I don’t want to turn

into a sneeze!

In this poem Jane Medina is validating Jorge’s name and the name of every immigrant child. Jorge is not a sneeze; he is a child. Even though George is the literal translation for Jorge in English, for the child it is a completely different word not related at all to his name. This is my favorite poem of this book, because I can relate to it. In the United States, Rene is a girl’s name. Everyone that saw my name thought that I was a girl. I could see the expression on their faces when they saw me responding to René, my name.

Immigrant children are very smart. However when they do not speak the language of instruction they cannot do the work. From one moment to another, their self-esteem drops. They are not brilliant anymore. Jane Medina writes:

Why am I dumb?

In my country

I was smart.

All tens!

Never even an eight!

Now I’m here.

They give me

C’s or D’s or F’s

-like fives

or fours…

or ones.

Well,

I’m still smart

in math.

Maybe dumb

in reading.

But math-

-all tens,

I mean,

A’s.

This poem describes the daily reality of immigrant children in schools around the country. I saw my own reflection in all Medina’s poems. For me Math was the safety belt that kept me from falling out of the English car that I tried to drive. Numbers are numbers anywhere.

It is very hard to see smart children struggle at school because they cannot do the work. It is typical for these children to fail a test. It could have been an easy test for any child who spoke the language. However, for immigrant children this strange language is a barrier too high to jump. In the poem The Test, Jane Medina writes:

I felt my black eyes

get blacker as I stared at the test.

Mrs. Roberts took a step.

I turned my head and she was looking at me.

She saw the tears

-like thick glasses stuck to my eyes.

We both tried to ignore them.

I push the paper away.

This test is too hard for me.

This poem can touch the heart of every immigrant child, because “This test is so hard for me,” is a very common phrase for these children. Immigrant students make up a large majority of children who drop out in big cities; children that could not do the work that teachers expected.

Jorge enters into the silent period. His heart jumps every time his teacher asks a question. This is not because Jorge does not know the answer. It is because, he is afraid of speaking English.

Invisible

If I stay very still

and breathe very quietly,

the Magic happens:

I disappear

-and no one sees me

-and no one hears me

-and no one even thinks about me

And the teacher won’t call on me.

It is very safe being invisible.

I’m perfect!

I can’t make mistakes

-at least nobody sees them,

so nobody laughs.

I have been the invisible student sitting in the last chair at the back of the classroom hoping that the teacher would not call on me. The first time that a teacher asked me to read an English text, I froze. I read the text using my Spanish phonic skills. Everyone laughed, I did not know why. From that day on, I decided to be invisible.

The silent period takes a long time. Especially when there is no support from peers and adults. For immigrant children this period is even harder when their native language is not appreciated. In Dirty Words, Jane Medina writes:

I wish my language didn’t

sound like dirty English words.

The grown-upsfrown

when I speak Spanish,

and the kids laugh.

All immigrant children in the United States can reflect on this poem. Jorge needs the affection from a teacher who can help and support him. When immigrant children see the work of their English-speaking classmates, they feel insecure even if they are doing their best. In the poem Sneaky, Jorge wants to hide his paper.

I hid the paper inside a

big, wavy, white stack of papers

on my teacher’s desk.

I want her to see it

-but not till after school.

I’m scared that it’s not good enough.

I think I spelled too many words wrong,

but I don’t know which ones.

I hope she understands it.

I hope she likes

me.

In this poem Jorge does not care as much about his paper. In the last line, just by using a word, me, Medina reveals what Jorge really needs, the affection of his teacher.

In my high school, at the beginning of the semester in an English Composition class, my English teacher asked the English learner students to raise their hands. Then she told us that most immigrant students failed her class. The teacher said that it would be a good idea to visit our counselors and ask for an easier class. This class was a college requirement. Even though I felt insecure, I decided to stay. A week earlier, I had sent my college applications to three universities. Like Jorge, I needed someone who believed in me. Many times a little affection and love from teachers can do wonders for immigrant children.

Jorge enters the fifth stage of uprooting, assimilation/ acculturation into the mainstream, when his teacher begins to believe in him. Jorge begins to feel proud of his work. He is not dumb anymore. He has hope that he could be smart again. In the poem My Paper, he is excited.

My Paper

She held up my paper

and all the noise stopped.

Everything became still.

Everyone turned their heads

To hear the words she read

-my words.

Then their eyes became a bit wider,

and their pencils moved a bit faster,

and I grew a bit bigger,

when she held up my paper

and all the noise stopped.

Immigrant children need to see more stories and poems like My Paper. They have to see positive role models in literature. When immigrant children read about characters like themselves who are struggling at school and finding ways to resolve their problems, they receive a message of hope.

In this English class, I paid attention, did all the work, and studied for many hours. One afternoon, the teacher was very upset because no one followed her instructions for one composition. She showed the class, the only paper that followed the rules; it was mine. My teacher smiled at me. That simple smile transformed my fears into hopes in that English composition class. I can proudly say that I got a B+ as my final grade in Miss Bass’ class. With effort and perseverance from the students and affection from the teacher, immigrant children can begin to see the light at the end of the tunnel.

Now that Jorge is acculturated he is ready to defend and validate his name by himself. Jane Medina presents a proud Jorge that even gives his teacher a lesson in the poem T-Shirt.

Teacher?

George, please call me “Mrs. Roberts.”

Yes, Teacher.

George, please don’t call me “teacher!”

Yes, T- I mean, Mrs. Roberts.

You see, George, it’s a sign of respect to call me by my last name.

Yes…Mrs. Roberts.

Besides, when you say it, it sounds like “t-shirt.”

I don’t want to be turn into a t-shirt!

Mrs. Roberts?

Yes, George?

Please, call me “Jorge.“

Good for Jorge, he could defend himself. This is another poem that defends the native roots of every immigrant child. I could never defend my name by using words. When people said, “Oh, you are a boy!” I only nodded with pride. As an adult, I had the urge to defend my name. I Am René, the Boy/ Yo soy René, el niño, my second picture book was the way that I found to tell everyone the meaning of my name. I am pleased that it became a picture book with a good role model for immigrant children.

At the end of her book Jane Medina has an acculturation story. Jorge will not lose his roots. He lives and studies in the United States, but he will always be Jorge on both sides of the river.

Jane Medina was born in the United States but her husband immigrated to the United States from Mexico as well as most of her friends and students. In a telephone conversation with the author, she said:

I have lived the immigrant experience through my husband, friends and students. Jorge was one of my students in my fourth grade classroom. One year later, I saw him sitting on a bench. He did not look very happy. He told me that his new teacher called him George. He did not like it at all. It was then and there when I decided to write this book.

The result was this wonderful book that touched me very personally. Jorge is me, a student trying to do his best at school but struggling with his identity and a new language. This book is authentic because it reveals the struggles of immigrant children in Jane Medina’s classroom.

Jane Medina believes that there are many multicultural books that are not authentic. She has read many immigrants stories that go from one extreme to another--either all sweetness or a horrific experience. She says:

An immigration story needs to be three dimensional in order to be authentic. To say that to immigrate to another country is easy and wonderful is a lie. To say that to immigrate to another country is the worst thing that could ever happen to you is a lie too. To be genuine, an author must show the good things, the bad things, and also the ambivalent. The author needs to write a real story.

René Colato Laínez

A Movie in My Pillow/ Una película en mi almohada is a collection of 21 poems written by Salvadoran author Jorge Argueta. In these poems Jorge Argueta evokes the wonder of his childhood in rural El Salvador, his experiences of being an immigrant, and his confusion and delight in his new urban home in San Francisco’s Mission District.

Argueta comes from a war torn country. Bombings, shootings and danger of being killed in the streets are common fears and anxieties that immigrant children from war torn countries have in common. In his poem With the War, he writes:

Streets

became so lonely.

Doors

were made of metal.

Wind

kept on howling.

And we never

went out to play.

What little Jorge really wants is a place where he could go out and play. Unfortunately, during a war kidnappings, bombs, and shootings occur on a daily basis. There is no secure place for anybody. Children in war torn countries have to play inside their houses. I can relate to Argueta’s experience because I was a child during the civil war in El Salvador. The only place I felt secure during the long and dangerous shootings was under my bed.

Argueta combines the first two stages of uprooting, mixed emotions and excitement or fear in the adventure of the journey, in the poem When We Left El Salvador.

When we left El Salvador

to come to the United States.

Papá and I left in a hurry

one early morning in December.

We left without saying goodbye

to relatives, friends, or neighbors.

I didn’t say goodbye to Neto

my best friend.

I didn’t say goodbye to Koki

my happy talking parakeet.

I didn’t say goodbye to

Miss Sha-sha-she-sha

my very dear doggie.

When we left El Salvador

In a bus I couldn’t stop crying

because I had left my mamá

my brothers and my grandma behind.

Little Jorge like many immigrant children does not have time to get used to the idea that he is leaving his country. He does not even have an opportunity to say good-bye to his loved ones. Separation from family members is a terrible fact in war torn countries. Immigrant children do not know if it will be the last time they will be able to see their family alive. It is a double separation. The hope to be together again is in the heart of immigrant children but reality is telling them that this hope could become a nightmare if the family they left behind dies in the war. This poem touches the heart of immigrant children from countries in war.

Little Jorge comes to the United States and enters the third stage of uprooting, curiosity. In Wonders of the City Argueta writes:

Here in the city there are

wonders everywhere.

Here mangoes

come in cans.

In El Salvador

they grew up on the trees

Here chickens come

in plastic bags.

Over there

they slept beside me.

For little Jorge living in a modern city was like a fairy tale scene. When my mother and I went to the shoe store for the first time, I was amazed when I saw the door open by itself. It was like magic.

Little Jorge enters into the fourth stage, culture shock that exhibits as depression and confusion. It does not happen at school; it happens at his house. In Sidewalk Snakes he is afraid of losing his father.

Don’t step on the snakes Papi.

Don’t step on the sidewalk snakes.

Can’t you see that they are cobras?

If you step on them

they will wake up and tangle

around your legs.

Then they will sting you.

They will bite you

and you will be very sleepy.

Jorge’s father is the only loved one living with him. If something happens to his father, Jorge will be alone. For immigrant children who are separated from their loved ones, this stage is crucial and painful. When I knew that my older brothers were coming, I marked the date on the calendar. If everything went fine, they would arrive in ten days. On the 11th day, I could not sleep. On the 12th day, I prayed to all the saints in heaven. That same day, we received a call from an immigration detention center. My brothers had been caught when they were crossing the border.

Immigrant children deal not only with problems at school, but also with their internal feelings about missing their relatives. In Voice from Home Argueta describes his relationship with his grandmother.

From my uncle Alfredo

I received a great surprise-

a packet in the mail

from El Salvador.

Inside I found a tape

with my grandma’s voice

talking and singing to me

In Nahuatl and Spanish:

“Jorge, Jorge, maybe

you will never come back.

Remember when you sat

next to me in the river bank?”

“Jorge, Jorge, don’t forget

that in Nahualt ‘tetl’

means ‘stone’ and ‘niyollotl’

means ‘my heart’ ”

This poem reminded me of my grandmother who died a month after I arrived in United States. My mother and I did not have a chance to attend her funeral. I never even had the chance to say good bye.

Little Jorge is in the last stage of uprooting, assimilation/ acculturation into the mainstream, when he reunites with his family. For immigrant children, this event is wonderful. There will always be problems in the new country but now they have the support of their families. Together everything will be easier. In Family Nest Argueta writes:

Today my mamá

and my little brothers

arrived from El Salvador.

I hardly recognized them

but when we hug each other

we feel like a big nest

with all the birds inside.

This is a wonderful poem of family reunion and every immigrant child can relate to it. My parents hired an immigration lawyer to defend my brothers. They got a temporary visa to stay in the United States for six months. We celebrated our reunion for many days.

Jorge acculturates. He is ready to become whatever he wants. His family gave him the hope that he was longing for. Argueta concludes the book with A Band of Parakeets.

Every Saturday morning

Mamá and Papá

my little brothers

and I walk

on 24th Street.

We are like a band

of parakeets flying

from San Francisco

to El Salvador

and back again.

After my brothers arrived in the United States, I felt more secure at home and school. Now I had someone to talk to after school. They helped with my math and I helped them with their English. Like Jorge’s family we were a band of parakeets.

The pensive yet playful character of Jorge in A Movie in My Pillow/ Una película en mi almohada voices Argueta's own challenges and joys in adjusting to a drastically different landscape. Also, he is reflecting the voices of other Central American immigrants that he worked with in a homeless shelter. Jorge Argueta is writing from these personal experiences. He is one of the estimated 500,000 Salvadorans who immigrated to the U.S. in the 1980s due to a cruel civil war. In an interview with Criticas Magazine, Argueta said:

To write an authentic and realistic story, you have to live it, suffer it, and learn from it. El Salvador is in everything I write. My books are not only my stories but also the stories of thousands of Salvadoran children who left their country during the civil war in the 80’s. I believe that immigrant kids and adults from El Salvador as well as those from other countries and cultures, will see themselves reflected in this book because its main theme is immigration.

A Movie in My Pillow/ Una película en mi almohada is one of my favorite bilingual books. When I discovered this book, I jumped with joy. This was the first picture book about a Salvadoran boy published in the United States. As a Salvadoran, I felt proud of this book. Jorge Argueta tells my immigration story.

Jorge Argueta wants to be a role model to immigrant children. He visits school classrooms all around the United States.

"I stand in front of the children who look like me and say, “I am an author, and these are my books.” That makes children feel good. They want to write books too. Children are natural poets; I simply show them a word game and explain that poetry helps us to express happiness, anger, beauty, pain, and all the other amazing feelings life offers. Words make us fly I tell them, and indeed, we fly."

Argueta inspired me to fly and to tell my Salvadoran stories. To this day, there are only two Salvadoran authors writing picture books for children in the United States: Jorge Argueta and me.

Rene Colato Lainez

In My Diary from Here to There/ Mi diario de aquí hasta allá, Amada Irma Pérez writes about her own journey as a girl crossing the border with the help of her family. In her diary little Amada records her fears, hopes, and dreams for their lives in the United States.

Amada is happy living in Mexico, but one morning she hears that her parents want to come to the United States. Amada is very worried. She experiences the first stage of uprooting, mixed emotions:

“Dear Diary, I know I should be asleep already, but I just can’t sleep. If I don’t write this all down, I will burst! Tonight after my brothers- Mario, Víctor, Héctor, Raúl, and Sergio- and I climbed into bed, I overheard Mamá and Papá whispering. They were talking about leaving our little house in Juárez, Mexico, where we’ve lived our whole lives, and moving to Los Angeles in the United States. But why? How can I sleep knowing we might leave Mexico forever?”

Amada is the typical immigrant child who is already rooted to her country and culture. She is like any child in Latin America who enjoys playing with her friends, going to school, and reading and writing in her native language. When I came to the United States, I was fourteen years old. I had nine years of instruction in Spanish. Like Amada in Mexico, I was rooted to my Salvadoran soil.

For immigrant children who are already rooted to their countries, the idea of leaving a known territory for an unknown dark place is terrifying. Amada is in shock. She loves her house, friends and speaking Spanish everywhere. She worries:

“But what if we’re not allowed to speak Spanish? What if I can’t learn to speak English? Will I ever see my friend Michi again? What if we never came back?”

These are typical questions that immigrant children have when they leave their countries. I was worried that I did not know how to speak or write in English. Before we left El Salvador, I tried to write a sentence in English. The Spanish/English dictionary was very wordy and heavy. After the third word, I quit, “I go to Estados Unidos con mi mamá.” (I am going to the United States to be with my mother). English seemed something impossible.

Amada and her family leave and the journey begins. Amada is in the second stage of uprooting, excitement or fear in the adventure of the journey. She says:

“Our trip was long and hard. At night the desert was so cold we had to huddle together to keep warm…Mexico and the U.S. are two different countries, but they look exactly the same on both sides of the border, with giant saguaros pointing up at the pink-orange sky and enormous clouds.”

When I left my country I traveled with only my father. Neither he nor I had ever been to the United States. I left behind my grandmothers, brothers, sister, and most of my extended family members. Some immigrant families make numerous intermediate stopovers for different lengths of time in several places. Amada and her family go to Mexicali and stay in her grandma’s house. Because Amada’s father is an American Citizen, he is the only one who can cross the border. Amada is terrified. She loves her father with all her heart. Immigrant children can relate to this authentic experience. Many children suffer through a separation from their parents when they immigrate.

Amada and the rest of the family wait at the Mexican border for the green cards that her father is trying to get. All this time, Amada is writing in her diary all her experiences about her journey. Finally, the papers are ready and Amada can cross the border.

“What a long ride! One woman and her children got kicked off the bus when the immigration patrol boarded to check everyone’s papers. Mamá held our green cards close to her heart.”

Amada does not go through the third stage, curiosity, but her brothers do. They go through this stage when they are still in their Mexican house.

“The big stores in El Paso sell all kinds of toys!”

“And they have escalators to ride!”

“And the air smells like popcorn, yum!”

Most immigrant children have only seen the United States in American movies. America looks like paradise, the land of promise and opportunities.

Because this book is about Amada Irma Perez’s journey to the United States, she does not write about the fourth stage of uprooting, culture shock that exhibits as depression or confusion. However, we can tell that since the beginning of the story, she has been in this stage. She even makes references to the silent period, when she writes that she is afraid that she would not be allowed to speak Spanish and she would never learn English.

At the end of the story, Amada is in the final stage of uprooting. She has acculturated to the mainstream. She goes to school to learn English. She discovers that changes are not easy but that she can overcome any fear with the help of her family.

“Just because I’m away from Juárez and Michi, it does not mean they’re not with me. They are here in your pages and in the language that I speak; and they are in my memory and my heart. Papá was right. I am stronger than I think--in Mexico, in the States, anywhere.”

Amada Irma Perez presents an authentic immigrant story. Many immigrant children living in the United States can relate to her feelings about leaving her country and her separation from her father.

René Colato Laínez

When immigrant children come to the United States, they experience a variety of emotional and cognitive adjustments in the new country. They have left behind a language, a culture and a community. From one moment to another, their familiar world changes into an unknown world of uncertainties. These children have been uprooted from all signs of the familiar and have been transported to an unfamiliar foreign land. In the process of adaptation, immigrant children experience some degree of shock. In the Inner World of the Immigrant Child, Cristina Igoa writes:

"This culture shock is much the same as the shock we observe in a plant when a gardener transplants it from one soil to another. We know that shock occurs in plants, but we are not always conscious of the effects of such transplants on children. Some plants survive, often because of the gardener’s care; some children survive because of the teachers, peers, or a significant person who nurtures them during the transition into a new social milieu."

Latino authors use their experience of being uprooted from their country of origin, being transplanted to the United States and their adaptation to a new culture in order to authentically and realistically portray the immigrant experience in picture books.

Stages of Uprooting

Immigrant children go through stages of uprooting to adapt to a new country: mixed emotions, excitement or fear in the adventure of the journey, curiosity, culture shock that exhibits as depression or confusion, and assimilation/ acculturation into the mainstream. These stages are not universal truths for all children and they may occur simultaneously or in varying degrees (Igoa).

During the first stage of the uprooting, children experience mixed emotions when the parents tell them that they will be moving to another country. Sometimes they are not informed until the actual day their journey begins. Most of the time the children do not know where they are going. They only know they must go because their parents are going. They do not have a choice.

In the second stage the children experience excitement or fear during the journey by train, car, plane, boat or on foot. They are usually with a parent or relative, and there is much discussion among them in their own language. The long and tiring journey begins.

The third stage of uprooting, curiosity, occurs when children arrive in the new country. At first everything looks good. After a tiring trip, the immigrant children relax. For them everything looks good and new, especially if the children come from a poor small town or a war torn country. Everything is like a miracle, big buildings, warm water, carpet on the floor, etc.

During the fourth stage, culture shock that exhibits as depression or confusion, the dream or curiosity disappears and for the immigrant children the nightmare begins. This is the more traumatic stage in the lives of the immigrant children. They need to go to school. They are now separated from the warmth of extended family members and their native language. Immigrant children may become depressed or confused and let down. They may enter a silent period, keeping their emotions inside.

During the last stage, assimilation/acculturation into the mainstream, immigrant children face pressure to assimilate/ acculturate to the new country.

Authors Suárez-Orozco describe three different styles of identity adopted by children of immigrants in their book Children of Immigration: ethnic fight, adversarial identities and bicultural identities. In the ethnic fight, some children abandon their own ethnic group and mimic the dominant group. Immigrant children assimilate and become carbon copies of the new culture. They give up their values and ways of behaving to become part of the mainstream culture. If the adversarial identities style is adopted, children construct an identity in opposition to the mainstream culture and its institutions. Children do not care about the dominant society. They do not make an effort to learn English and, most of the time, they return to their countries. If children adopt a bicultural identity, children develop competence to function in both cultures. Immigrant children acculturate and become part of the mainstream culture without discarding past meaningful traditions and values.

I will examine the work of Latino authors who have experienced the phenomenon of uprooting. By analyzing their work and learning about their uprooting process through published and personal interviews and by comparing them with my own immigrant experience, I will explore the topic of authenticity in the picture book format.

In order to write about identity in immigrant children, authors need to write an acculturation story, a story where the protagonist becomes part of the mainstream culture without discarding their language and culture. These Latino authors validate the children’s names, language, roots and culture. They want immigrant children and any other reader to feel proud and happy about their roots.

Below is a link about how the success of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings films led to the impossibility of Golden Compass sequels.

http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2012/05/25/indie-blockbuster-franchise-is-not-an-oxymoron/

In short LoTR and Golden Compass were both financed the same way (pre-selling intl distribution rights of a trilogy to finance the first installment). But when parent company Warner Bros. absorbed New Line, WB did not want to make the Dark Materials sequels because they contractually would not be able to distributed them themselves overseas (where the first film made $300 million [it did do poorly here in the US though]) because the intl distribution rights were already held by a variety of local distributors across Europe and Asia.

I tried to get through the book and I was just…bored. I don’t get the love for it at all.

I was fine with it until the last five pages, then that was it. You don’t kill children. Never had any urge to read the others, especially with the bogus theology. Pthagh.

I was waiting for this series to show up…am so glad it’s this high on the list. Brilliant, magical writing.

This is one that I just don’t get. I only read Golden Compass, and didn’t bother with the others because I found GC to be quite boring. Maybe one day I’ll go back and re-read, but at this point I’m not in any hurry.

I also only read the first one and didn’t have any desire to read the others. I also still don’t believe that this is a children’s book. As far as I’m concerned it’s strictly in the YA camp.

I was amused by this detail: Many voted for The Golden Compass. Many voted for The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. I didn’t notice anyone vote for both! (Though I may have missed some who voted in the form.) I’m firmly team LION myself, though I did find this book impressive. Not exactly lovable, though.

(I find this amusing because I believe Philip Pullman talked about writing this book as an atheist’s response to C. S. Lewis.)

And the whole issue of alternate worlds? To me that goes against the very point of Story. If there are infinitely many other worlds where Lyra is making other choices, well, then why the heck tell us about this one?

You do have to give him that he’s mighty good at world-building.