By Andrew Zurcher

The “Februarie” eclogue of Edmund Spenser’s pastoral collection, The Shepheardes Calender, was first published in 1579. It presents a conversation between two shepherds, a brash “Heardmans boye” called Cuddie and an old stick-in-the-mud named Thenot. The two of them meet on a cold winter day and get into an argument about age: Cuddie thinks Thenot is a wasted and weak-kneed whinger, while Thenot blames Cuddie for his heedless and slightly arrogant headstrongness. To support his position, Thenot tells a moralising tale about an ambitious young briar and a hoary oak. In his eagerness to flaunt his brave blooms full in the sun, the briar persuades a local husbandman to chop down the mossy tree; but the end of the tale turns bitter for the little plant when, deprived of the sheltering support of his onetime neighbour, he is utterly blown away in a heavy gale. Thenot is in the middle of applying the moral of his tale when Cuddie interrupts, and leaves in a huff – petulant and dismissive to the last. As the eclogue breaks off, the reader is caught in an old-fashioned and hackneyed dilemma: is it better to embrace the beautiful but rootless new, or cling to the solid, gnarled old?

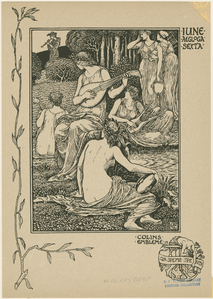

The Shepheardes Calender poses this gnarled horn of a problem in the middle of a printed book that, itself, has already begun to play in a very material way with the tensions between antiquity and newfangleness. Spenser’s eclogues are conspicuously modeled on those of Theocritus and Virgil, Marot and Mantuan. The poems were first published elaborated with E.K.’s prefaces, his introductions (or “Arguments”) to each of the twelve “aeglogae,” and his explanatory notes. These annotations are presented in a Roman type that contrasts visually with the black letter of Spenser’s poetry, framing it in a style that emulated early modern editions of Virgil’s eclogues, as well as the theological and legal texts that, in this humanist period, were often produced entirely engulfed in glosses and comments. Each of the eclogues is also accompanied by a woodcut, done in a rough style, and concludes with an “embleme” apiece for each of the eclogue’s interlocutors. These archaising features belie the novelty of Spenser’s project – the first complete set of original pastoral poems in English, and a collection that, in its allegorical engagement with the history of England’s recent and successive reformations, put this country and its fledgling literary culture on the map. Here at last was England’s Virgil, said Spenser himself. Just look at his book. But is it an old book, or a new book? Is it new-old, or old-new? What is the meaning of the new, if it be not interpreted by the old?One of the most exciting aspects digitizing works such as in the Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) project is