new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: University of Pennsylvania, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 95

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: University of Pennsylvania in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

I made a mistake this past semester at Penn. I failed to go see Eileen Myles. She was there, in two-day residence, and I might have grabbed a seat when Al Filreis was doing one of his famous Kelly Writers House Fellows interviews, but I allowed my overwhelm (and the late SEPTA trains) to rule me.

So I didn't see Myles talk. And my students—David, Nina—they shook their heads. David said, Here, borrow my book, but of course I would not take it, for he'd written his own words next to hers and his whole body spoke of admiration. Nina said, She really was so good, she really was (Nina's gorgeous big eyes looking so sad for me). I shook my head, apologized.

Then I bought

Chelsea Girls. I shook my own head at me. Because Myles writes like somebody smart might talk—rapid fire, scandalous, self-enthralled and self negating. She is beautiful and demanding. She needs and she takes. She hopes her poetry is part of her goodness, she steals from her affairs, she thinks a lot about what she wears (orange pants and bleachy shorts and Madras shirts and nothing), she has a lot of sex. And by the way, this is not memoir (it says novel on the cover), but the character is Eileen Myles and in the novel Eileen Myles does a lot of stuff (gets her photo taken by Robert Mapplethorpe, say) that Eileen Myles actually does in real life.

What I liked most: the nearly inscrutable ineluctable gorgeous stuff that forces your reading eye to stop. Sentences like these:

The whole process of your life seemed to be a kind of soft plotting, like moving across a graph which was time, or the world.

You knew she was a good person because she held back at moments of deepest revelation. She did not spill, and I always felt that to push her a bit would be sloppy and expose my own lack of a system of conduct.

You can't force a story that doesn't want to be told.

It's lonely to be alive and never know the whole story. Everyone must walk with that thought. I would like to tell everything once, just my part, because this is my life, not yours.

What I think: Like Anne Carson, Maggie Nelson, Paul Lisicky, Sarah Manguso, others, Myles is a form breaker, a smasher-up of words, a funny person with a serious talent. I should have seen her talk.

And so—reading of each other, to each other—we said goodbye today at Penn. These are my mighty fourteen who dared to take on the memoir beast...and won. The mighty fourteen who provoked my tears—and allowed me to cry them.

And that, above, is Cole Bauer, our Mr. Music Man, whose guitar work accompanied the gorgeous

Beltran audio recording on home. Cole is a singer-songwriter who packs in the crowds at a local bar on Monday nights. Cole is the guy who wrote, throughout our time together, with hope-restoring heart. It's uber cool to love those who love you. Cole reminded us of that every time we met.

Listen.

Then go ahead and buy your copy of "Small Town,"

here.

It's an increasingly interesting thing—this writer/teacher role I play. I've been at it long enough to note the shifts in student needs and expectations, to be able to predict, better than I once could, what books, passages, and lines will inspire, which exercises will illuminate and which will stress, which days will quiver with hope, and which with longing.

But I can never summon, in the my mind's eye, the

particular students who will find our classroom at 3808 Walnut on Tuesdays each spring. I can never predict the stretch of soul and commitment. When I first met Nina Friend last year, I saw beauty and height, enormous kindness and care, a young writer who could certainly place a sentence (or several, more) on the page, that generous type who shared her mother's cookies and who always offered more.

When Nina set out to write her honors thesis with me this year, we both knew that food would be involved, as well as Nina's passionate interest in the lives of those who serve. Over the course of many months, Nina went from restaurant to restaurant, from book to meeting, from interviews with famous people to serving herself. She wanted to see, as she writes in her thesis, beyond the performance. She wanted to know who was happy as they served—and when and why. She asked whether "serving others can coexist with serving oneself."

A supreme perfectionist, a writer who deeply cares, a young woman who asked for more and more critique—and who absorbed it, faithfully, returning each time with a thesis of ever greater grace and magnitude, Nina has gone behind the lines in her thesis—a work that will change its readers and remind them always (a perpetual nudge) to look harder at the person announcing the day's specials.

Nina, like David Marchino, whose thesis

is featured here, has given me permission to share some of her work with you. I'm scurrying out of the way so that you can meet Nina and her cast of characters yourself. This is from the chapter called "Community."

Community

Crisp and golden, it’s propped in the middle of a silver platter that’s been in the family forever. A heap of crumbled bread forms a moat around the centerpiece. Stuck together with orange juice, flavored with parsley. The first cut slices the bird on its side. Succulent. Soft. A ladle filled with gravy. A spoonful of stuffing. Two helpings of pecan pie. Chocolate mousse. Whipped cream.

* * *

When Ellen Yin opened Fork Restaurant eighteen years ago, she wanted the

space to feel familial. The mosaic floor was laid down by a neighborhood tile guy. A local ironworker made the chandeliers. A fabric designer in the area crafted lampshades. Tony DeMelas says the restaurant instantly became “a community of artists and love.”

When Yin decided to revamp the restaurant in 2012, she called up Tony to create

a mural. Something to hang over the brown velvet couch that stretches across an entire

side of the restaurant. Tony was honored to be able to create something for the restaurant

he worked in.

When Tony was working on the mural, Chef Eli Kulp would drop by his studio.

Just to keep him company. Just to be there. “He was very hands-on,” Tony says. Kulp

was the only chef that has ever influenced Tony’s work. He was infatuated with the way

Kulp composed his plates. The way he could make a rib look like a log in the woods with

flowers blooming out of it and mushrooms growing from tiny cracks. His food was

sculpturesque. Tony says, “I’d look at [Eli’s plates] and go, ‘[If] you just blew this up and

abstracted it…and put it on a canvas, you could sell the hell out of this thing.’”

Tony’s mural hangs above the extra-long couch and reflects its color onto the

dark wood tables. Yellows and oranges and light greens and white and brown. A forest of

tree trunks, abstracted.

Tony used to walk past the painting hundreds of times every day as he hustled

from Fork’s kitchen to his tables, balancing plates in his arms. Customers would come in

and sit down and admire the mural. They would say things like, “Oh, it’s so much bigger

than in the pictures!” They would be waited on by Tony – with his square, tortoise-shell

glasses and eyes that feel like he’s staring into your soul – and they would have no idea

that the humble man taking their orders was the artist who painted that masterpiece.

* * *

Community can be built into a place. But it’s the people within that place who

decide whether community flourishes or dies.

You have heard me speak of my two honors thesis students. Tuesdays we'd meet. Through the week we'd talk or write. Sometimes I'd see pages. Sometimes I'd wait for pages. Always I was here and they, my students, were where they had to be: sifting, thinking, wording, revising, making the story what it had to be.

David Marchino, the guy who taught me jawn and green hair, bamboo and patience, the healing power of a boyhood friendship, taught me even more than that with his memoir,

He Will be Remembered: A Father's Crowded Life. In these tight, proud, poeming pages, David recalls the father he loved, lost, and recovered, if only for now. The cemeteries where the dead appease the living. The religion of his parents' cocaine. The power of a recovered briefcase. The voices of plead and promise. David speaks through namesakes. He tunnels through memory. He comes out the other side, burnishing truth with myth—the opposite, too.

David has given me permission to share the opening pages of his memoir with you. I do that here, with deepest respect for the journey David has taken and the words he has produced. With the greatest possible sense of honor that he allowed me to stand on the sidelines and cheer him on.

David Marchino. Writer. True.

From the (near) beginning:

He is not hard to find. He may arrive when you speak his name, or when you curse it. A magician whose default state is disappeared. His greatest trick is presence. My father—eight years gone—now back. Ta-da.

He looks worn, like he’s spent the last few years disappeared in a pothole. Like his body has finally exhausted its last expanses of youth. The man is tired. His arms, his legs, his skin. He’d been virile once, you could tell. I remembered how the skin tightened around his biceps, how he’d make the panther on his arm roar. He’d always been a little slight—not more than five-and-a-half feet—but now he looks unsteady.

“Hello, Sonny,” and I am fourteen again: his grip on the back of my neck, his prickly lip on mine. Love that said I have you.

When he hugs me, I want to say I feel that slip away. His blustery love, the years gone. But I only feel in my arms a man who has stagnated, and he, in his, a son he no longer knows.

He sits me on his couch. He lies to me. He paces the floor and sips beer after beer. “Only four a day now,” he says as his eyes grow rheumy and soft. Hustling is still a part of his to day-to-day, only now there is safety. He is a supplier, never out on the streets for more than fifteen minutes and raking in more cash than he’s ever seen. I don’t doubt this. For the past eight years, I’ve had no significant contact with my father, but he came sporadically every now and again. A phone call at two in the morning, a wet whiskey-rasped voice. The few times I heard my father cry. It was desperation. He’d been dealing and had cut someone short. Word got around. They’d put the gun in his mouth. They’d hit him with a bat. The shapeless, omnipotent they were on the hunt for him. He was going to die.

I’d cry with him during these calls—I’m not sure a son can do anything else in that situation. But, when he hung up and I was left with just the dial tone, I felt sure Dad would be okay. He wrote the story of his life, circumstances be damned. My father was legend, was myth, was Roman God. As long as someone believed in him, he could never be lost.

He asks about a lot, never sitting down with me. It’s as much interrogation as it is plea. Questions are fired off with no space given to answer them. They are formalities more than anything else. He does not want my answers. He prefers his own. He reads our reunion as permission to rewrite the past, prune the truth to his liking. It is the hand that gripped my neck as a child and directed me, as though it clutched the handles of a bicycle. It reaches out for the past eight years of my life.

It’s desperation, I realize. We fear the unknown—the late-night creaks that resound from the basement as we try to sink into bed, the voices we are certain we hear calling our name as we make our way through a soulless alley. That is true fear: incalculable, unreadable. As my father looks into my eyes after all these years, he sees it in me. I am a void wrapped in his orange-ish, freckled skin. I come to him a changeling, a severed connection he is frantically trying to reestablish. We fictionalize what we do not know—an admission of ignorance and an appeal for enlightenment. A construction meant to give shape to the unknown. The gentle blue of the sky draped over the endless, infinite, abyss of space. To fit my life into some predetermined mold is, for my father, a means to close the gap between us. He pretends to know his son. It is easier that way....

Tomorrow, the work of Nina Friend.

I would have preferred a sharper photo. I could blame my fatigue at the near end of that day—my hands slipping, or my eyes watering, or something. Instead, I'll declare this photograph of Joan Wickersham reading at Penn's Kelly Writers House to be infused by the light Joan carries with her. As she works. As she reads. As she considers. As she listens.

Joan was at Penn to read from three works—nonfiction (

The Suicide Index), fiction (

The News from Spain), and poetry (

Vasa Pieces, parts of which appear in

Agni 82). Her coming was, for me, a highlight of this semester—a chance to hear from a writer whose work has long inspired and thrilled me. A chance, too, thanks to Joan's invitation, to spend an hour or so alone with her over steeping, seeping cups of berry tea. We talked advertising youths,

Lab Girl, place in memoir, the confounding role of adjunct teachers, Philadelphia then and now. I discovered, in Joan, that rare, wonderful thing: a person as gloriously complex and broadly thinking in person as she is on the page.

And then there she was, reading. Words I'd read twice, sometimes three times before, but delivered newly. A culminating sequence from

Vasa Pieces—new work inspired by the sinking and resurrection of the Swedish warship,

Vasa. Beautiful pieces made thrilling by their emergence from history and their threads of urgent now. The first poem setting the tone, revealing the "must" of this work—the role the

Vasa played in the imagination of Joan's husband:

... I imagine you down there,

reading and re-reading the story of Vasa,

memorizing every picture, puzzling over the order—

the heeling ship, the sinking ship, the risen ship,

the sunken ship, the battered risen ship again—

clinging to the table leg, pretending it was a mast.

Poems continuing on through ships (and lives) gone wrong, through autobiographies redesigned by survivors, through shipworms and felt absence.

Until Joan lifted her head. And even then, her spell was not broken. The light still broke behind and through her.

I want to thank my students who attended for allowing this moment into their lives. I want to thank Jamie-Lee Josselyn, that lovely vision in green pants, for her beautiful introduction. I want to thank the Kelly Writers House for being home and hearth to both talent and soul, for being that place that students can and do turn to when the world feels raw and bright minds are the cure.

I want to thank Joan for the afternoon, and for the inspiration of her commitment to the work itself. The work, above and beyond all else.

This past Wednesday afternoon and evening I had the distinct pleasure of spending time in the company of the great essayist and Columbia University professor (and head of the graduate nonfiction program), Phillip Lopate, his wife, his daughter, and members of the Bryn Mawr University creative writing program.

(Thank you, Cyndi Reeves and Daniel Torday, for allowing me to crash the party.)

Between the cracks of many deadlines here, I've been reading from the books I bought that evening. I have, of course, read Lopate through the years; who can teach nonfiction without owning Lopate volumes? But I did not own, until this Wednesday night,

To Show and To Tell: The Craft of Literary Nonfiction, which is, in a word, a glory. Perhaps it is because I agree so steadily with Lopate's many helpful assertions, perhaps it is because I, in my own way, attempt to teach and, in books like

Handling the Truth: On the Writing of Memoir, carry forward these ideals about the rounded I, the obligation to the universal, the curious mind, the trace-able pursuit of questions, that I sometimes read with tears in my eyes passages like this one, from "Reflection and Retrospection: A Pedagogic Mystery Story:"

In attempting any autobiographical prose, the writer knows what has happened—that is the great relief, one is given the story to begin with—but not necessarily what to make of it. It is like being handed a text in cuneiform: you have to translate, at first awkwardly, inexpertly, slowly, and uncertainly. To think on the page, retrospectively or otherwise, is, in the last analysis, difficult. But the writer's struggle to master that which initially may appear too hard to do, that which only the dead and the great seem to have pulled off with ease, is a moving spectacle in itself, and well worth the undertaking.

There are just two more weeks left in this semester at Penn. My beautiful honors thesis students are finalizing their work and, soon, will not just hold their glorious books in their hands, but have the time to reflect back on all the lessons learned. My Creative Nonfiction students are writing letters, Coates and Parker and Rilke style, to those they feel must hear them, while also working on 600-word portraits of one another. Joan Wickersham, the extraordinary writer of both

nonfiction and

fiction is headed to our campus, Tuesday evening, 6 PM, Kelly Writers House—and if you are anywhere near, I strongly suggest you make the time. She is a national treasure.

Teaching is exhausting, exhilarating, necessary, confounding, essential. I learn that again, year upon year. I stagger away—made smarter, in so many ways, by the students I teach.

When I talk about my students at the University of Pennsylvania—when I speak of their commitment to our work and to our community, the quality of their search and the depth of their answers, their sentences on the page—I am reflecting on what I love best about the school that once educated and now employs me. I am looking past the rumors and gossip and seeing straight into the heart of young goodness.

Because that goodness resolutely lives.

This semester I have again been blessed by the company of young people and their great talent. A few of my students have brought to class not just an interest in poetry or memoir or fiction, but a specific interest in young adult literature—an interest that has been heightened by my Penn colleague, Melissa Jensen. I've extended an invitation to any in the class to read from the library of new books that make their way to me—and to offer, here, their thoughts.

In this case, Emma Connolly—a young woman who practically defined memoir in her expectations essay, a young woman now looking ahead to a no-doubt stellar career (at least to start) as a middle grade teacher—took home my copy of Tara Altebrando's new and thrilling book,

The Leaving. I'd blurbed the book for Tara. I wanted Emma's thoughts. Here, in Emma's words, is what

The Leaving is all about.

You see what I mean about talent? Intelligence? Can you imagine Emma as the teacher she will be?

This is the Penn I love.

(And I love Tara, too.)

Who are you without your memories?

For the characters of Tara Altebrando’s engrossing, twisting, mysterious, “The Leaving,” this is not a hypothetical question. When five teenagers are dropped off in an abandoned playground eleven years after they went missing, they are celebrated and intensely questioned. Where were they? Who took them? And how can they be telling the truth that they don’t remember any of it?

As Scarlett and Lucas, two victims of the event known as “The Leaving,” and Avery, the left-behind sister of the only victim who has not returned, try to solve their own history, Altebrando confronts questions of identity, family, and memory. When Scarlett returns home to a mother who has attributed her disappearance to alien activity, she can’t shake the feeling that they are the ones who are from different planets. What if you don’t fit in where you’re supposed to? Lucas is disturbed by the discovery of skills that he must have learned during his absence. Can you be afraid of your past self? Meanwhile, Avery watches their return unfold as she continues to deal with the devastation that her brother’s disappearance has had on her family. Would she be better off like the victims of the “The Leaving,” able to essentially skip over a difficult childhood?

The characters discover unfinished leads from passed-away relatives and potential clues from past selves. They chase after jerkily recovered blips of memory that Altebrando visually represents by scattering words all over the page and interrupting the narrative with blocks of remembered images. With each revelation, we are drawn deeper into the search for answers before being thwarted yet again. Each time the story approaches acceptance of the fact that one might simply be better off not remembering, though, Altebrando reminds us, “Forgetting meant not knowing, meant ignorance, meant maybe making the same mistakes again and again.” So we keep searching, unable to leave this

book until the very last page.

In the early hours of this morning, I've been reviewing the final submissions to the Beltran Family Teaching Award chapbook—a collection of reflections on home by Penn students past and present; featured guests A.S. King, Rahna Reiko Rizzuto, and Margo Rabb; and the leaders of Penn's Kelly Writers House.

Trust me, please. The words (and images) are stellar and binding. No piece remotely resembles another. Each reveals and, in ways both quiet and surprising, sears.

I have crazy ideas, that is true.

But when those who join us that evening—March 1, 6 PM, Kelly Writers House, all are welcome—hold this chapbook in their hands and hear our guests and look out upon these faces, this particular craziness will not seem so very crazy at all.

Because it's them.

And they have spoken.

A huge thank you to my generous husband, who has spent untold hours by my side, laying out these pages.

Annie Dillard and Joan Didion will be our guides today in English 135. Voice and meaning will be our quest. We'll consider, for a moment, these two sentiments.

Can both be true?

“Why do you never find anything written about that idiosyncratic thought you advert to, about your fascination with something no one else understands? Because it is up to you. There is something you find interesting, for a reason hard to explain. It is hard to explain because you have never read it on any page; there you begin. You were made and set here to give voice to this, your own astonishment." — Annie Dillard, “Write Till You Drop”

And from this:

"We are all brought up in the ethic that others, any others, all others, are by definition more interesting than ourselves; taught to be diffident, just this side of self-effacing... Only the young and very old may recount their dreams at breakfast, dwell upon self, interrupt with memories of beach picnics and favorite Liberty lawn dresses and the rainbow trout in a creak near Colorado Springs. The rest of us are expected, rightly, to affect absorption in other people's favorite dresses, other people's trout."� Joan Didion, "On Keeping a Notebook"

Sometimes, as the first day of a new semester begins at Penn, I think of how very close I came to saying no to this opportunity all those years ago.

It would have been one of the greatest mistakes of my life.

And so, again, on this bitter cold day, we begin. We're focused on home this semester. We're reading Annie Dillard's

An American Childhood, George Hodgman's

Bettyville, and Ta-Nahesi Coates's

Between the World and Me, not to mention John Hough on dialogue and countless excerpts (countless as of now, anyway, because I can never tell what's going to inspire me before and during class). We'll be tapping into the new Wexler Studio—recording some of our work. We'll be laying the groundwork for the

Beltran evening on March 1—all invited—during which time we'll be visited by my writing friends (and worldly talents) Reiko Rizzuto, A.S. King, and Margo Rabb. We'll hear from former students. We'll write letters to the people in our lives, in Mary-Louise Parker and Ta-Nahesi style.

And today, if all the machines are working, we'll start out with

this.

I can't tell you why or how we'll use it.

You'll just have to imagine.

Meanwhile, before any of that, I get to share an hour with Nina and David, who will be writing their theses with me.

How lucky I am.

By:

Beth Kephart ,

on 1/8/2016

Blog:

Beth Kephart Books

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

home,

Margo Rabb,

Chicago Tribune,

Joyce Hinnefeld,

A.S. King,

Rahna Reiko Rizzuto,

University of Pennsylvania,

Kelly Writers House,

Debbie Levy,

Beltran Family Teaching Award,

home and literature,

Jennifer Day,

Add a tag

I've been working out ideas about home and literature, literature and home for awhile now, and on March 1, accompanied by friends A.S. King, Reiko Rizzuto, and Margo Rabb, my colleagues at Penn, and students past and present, I'll be doing even more thinking about the topic for the Beltran Family Teaching Award event at the Kelly Writers House at Penn.

My newest thinking, in this weekend's

Chicago Tribune (Printers Row), with thanks to Jennifer Day, Joyce Hinnefeld, and Debbie Levy, upon whom I seem to first try out my ideas. (Oh, Debbie, you're a gift.)

To read the whole story, go

here.

On Homecoming Saturday, in the Kelly Writers House on the Penn campus, I spent 75 minutes in conversation with Buzz Bissinger. It was a dialogue of many dimensions and much quiet—and authentic—self reflection.

That conversation can now be watched in its entirety

here.

By:

Beth Kephart ,

on 11/5/2015

Blog:

Beth Kephart Books

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Margo Rabb,

Jennie Nash,

A.S. King,

Rahna Reiko Rizzuto,

University of Pennsylvania,

Buzz Bissinger,

Beltran Family Teaching Award,

Ambler theater,

Book Garden Memoir Workshop,

Add a tag

Look for me behind stacks of books. That's where I'm living lately.

Assembling the content for a

traveling multi-day memoir workshop. Preparing to teach the personal essay during a morning/afternoon at a Frenchtown high school. Knitting together ideas for a four-hour Sunday memoir workshop, next weekend,

at the Rat (also in Frenchtown; places still available). Conjuring poem-engendering exercises for the fourth and fifth graders of North Philly. Building the syllabus for my next semester of teaching at Penn. Putting more touches onto the

Beltran Family Teaching Award event at Penn next spring (featuring Rahna Reiko Rizzuto, Margo Rabb, and A.S. King). Re-reading Buzz Bissinger so that I can introduce and then publicly converse with him at the Kelly Writers House this Saturday, for

Penn's Homecoming. Talking to

Jennie Nash about an online memoir workshop. Writing the talk I'll give this evening to kick off the

LOVE event (featuring film students and Philadelphians) at the Ambler theater. My writing (my novels) sit in a corner over there, where they have sat for most of this year. I'm sunk deep into the pages of other people's work. Their stories, their sentences, their churn: a thrilling habitation.

Every time I feel frustrated by a sense of career stall or perpetual overlook, I remember this: There are writers—truly great writers—who have gone before me, who have written more wisely, who have seen more clearly. I may want to be noticed, I may hope to be seen, I may wish to be important, a priority, first on a list, but honestly? Why waste time worrying all that when there is so much to be learned—about literature, about life—from the writers who have gone before—and ahead—of me.

James Agee. Annie Dillard. Eudora Welty. We could stop right there. Read all they've written. Make the study of them the year we live and it would be enough. It would be time well spent, time spent growing, time during which we learn again that aspiration must, in the end, be contextual. We can't hope to stand on a mountain's top if we don't acknowledge all the boulders and the trees and the ascent and the views that rumble beneath the peak.

My cure for my own sometimes literary heartbreak: Sink deep inside the work of others. Recall what greatness is.

By:

Beth Kephart ,

on 9/19/2015

Blog:

Beth Kephart Books

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Jay Kirk,

Wolverine,

University of Pennsylvania,

Kelly Writers House,

Al Filreis,

Tom Devaney,

Avery Rome,

Valley Fever,

Stephen Fried,

Greg Djanikian,

Hollywood Forever,

Julia Block,

Sidebrow Books,

Add a tag

I had a summer that didn't use much of my mind, so then I lost words. And my body, too, began to dwindle, only I gained weight in the process.

So when Jessica Lowenthal invited me to the reception honoring Julia Bloch, the new director of Creative Writing at Penn, I had many concerns. One: my wrong hair. Two: my wrong shoes. Also (like I told Jay Kirk and then Greg Djanikian and maybe even Tom Devaney and Avery Rome and Stephen Fried, but not my students Nina and David, or maybe I did, because I don't know, I was feeling irresponsible, and did I tell Al Filreis, too?, but I know I did not so burden Jamie-Lee Josselyn, Lorene Carey, Max or Sam Apple, at least I hope not), I had lost my personality. Left it somewhere. In the summer.

(Perhaps that's a good thing?)

But I went anyway, talking to my son by phone while in transit so that I would not turn back because, as I have noted, everything about me was not quite right, and if I'd not been talking with him, I'd have talked myself back onto the train and headed reverse west, for home.

Then I crossed the threshold at Kelly Writers House (there's always a little thrill involved) and everything changed. The place was just, well, filling up. With faculty members I respect and love, and students I adore. Soon (or, it actually happened first) Jessica herself was taking me on a tour of the new Wexler studio, and bam. I didn't look right, but something happened. I felt as if I belonged.

Then the star of our evening, the star of our program, stepped forward and faced a crowded, beaming room and began to read poems from

Valley Fever (Sidebrow Books) and

Hollywood Forever (Little Red Leaves Journal & Press, the Textile Series) and I, sitting there in the front row, began to feel a hot little prickle inside my head. Like the blank nothing of my thoughts was getting Braille-machine punched by all the delicious oddness of Julia's phrasing and syntax, occasionally repurposed lines, jokes I got and maybe didn't always entirely get (because, as I always say and forever mean, I am just not that smart). Julia was talking and then (I heard this) she was singing, but without any change in the pitch of her voice. Singing by exuding whole phrases in one long breath, then stopping (beat/beat) and starting again. It was like being driven in a car with the windows down, at night, when there is a lot of open road but also some bright red traffic lights.

Damn, I thought.

What do I mean, how can I explain this? These coupled and uncoupled ideas, the surreality of words you assume have been fashioned from parts, the winnowed down ideas that, when toppled and stacked, say something.

Mean something. Even if you can't actually always articulate what you have been stung by, you know you have been stung.

Here is half of "Wolverine," from

Valley Fever, a poem I instinctively love, also a poem I will ponder for quite some time.

Wolverine

I was only pretending

to be epiphanic

she said, tossing the whole

day over the embankment.

Is the heart collandered

or semiprecious

filled with holes

and therefore filled with light —

....

This afternoon, following a morning of work and a conversation with a friend, I read Julia's two books through, cover to cover. I hovered. I felt that warm thing happen again in my head, that invitation I will, as a writer and reader, always accept—to slam and scram the words around, to make the heart inside the brain beat again.

Thank you, Julia, for making my brain heart beat again.

And. You are going to be terrific. You already are.

By:

Beth Kephart ,

on 9/17/2015

Blog:

Beth Kephart Books

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Terry Tempest Williams,

University of Pennsylvania,

Mary Karr,

Joan Wickersham,

George Hodgman,

Helen Macdonald,

The Art of Memoir,

memoir,

Structure,

Rahna Reiko Rizzuto,

Add a tag

This morning, on HuffPo, I'm reflecting on why structure actually does matter in memoir — how indeed it helps to define the form—to distinguish it from autobiography, essay, war reporting, journalism, because that distinction matters. I refer in the piece to some of my favorite memoirs and memoirists, though there are, of course, many more.

And, because I must, I remember my brilliant students at Penn, and one particular Spectacular.

The full link is

here.

In my fourth book,

Seeing Past Z: Nurturing the Imagination in a Fast-Forward World, I wondered out loud about what might happen if we stopped competing with and through our children. If we gave them time to become themselves, to work together to build ideas and worlds that are never judged, prized, awarded.

Seeing Past Z was based on the many years I spent teaching children in my home and at a local garden. It was about the beauty of just being together, imagining together, writing together, and not mailing our poems, songs, stories out into the world for "greater" validation. I never re-wrote the children's work, never rewrote the work of my son. What they created they created. They took the pride of ownership. They gained.

From the opening pages of

Seeing Past Z:I want to raise my son to pursue wisdom over winning. I want him to channel his passions and talents and personal politics into rivers of his own choosing. I'd like to take the chance that I feel it is my right to take on contentment over credentials, imagination over conquest, the idiosyncratic point of view over the standard-issue one. I'd like to live in a world where that's okay.

Some call this folly. Some make a point of reminding me of all the most relevant data: That the imagination has lost its standing in classrooms and families nationwide. That storytelling is for those with too much time. That winning early is one bet-hedging path toward winning later on. That there isn't time, as there once was time, for a child's inner life. That a mother who eschews competition for conversation is a mother who places her son at risk for second-class citizenry.

The book was ahead of its time. It sold but a few thousand copies, was remaindered quickly. A few years later the slow parenting movement rolled in. Books about the importance of play and the dangers of the parent-governed resume grabbed headlines. Helicopter parenting was caught in the snare. The family counselors, the social scientists, the psychiatrists sat on the talk-show couches and asked, What have we done to our young?

Yesterday

The Atlantic ran an important story by Jen Karetnick titled

"Behind the Scenes of Teenage Writing Competitions." The story reminds us of the damage that can get done when teens (and those who oversee their paths to glory) write to win, write to build their resumes. The work is shaped (not always by the teens themselves) to beat the odds. The resumes grow, often at the expense of less-privileged children who don't have writing mentors and editors at their side. And programs designed to help these young people step toward the light are compromised by work that may or may not be the students' own. From the story:

This destruction of self-esteem and erasing of voice is exactly what Nora Raleigh Baskin, author of the new book Ruby on the Outside, fears. Having taught for almost 15 years at organizations including Gotham Writers Workshop, Raleigh Baskin has seen those mindsets trending. She refuses to critique manuscripts to send off to literary magazines or to judge competitions on the grounds that budding writers’ voices shouldn’t be “held up against a random opinion. This is the time for exploration and for encouragement … Writing is all about process and setting these arbitrary achievements takes away from that.”

For some young writers, that pressure can be far more insidious than the pain of rejection. The competitive spirit may persuade parents to hire well-known writers to tutor, edit, or even rewrite their children’s work. It may even lead minors down the path of plagiarism.

As parents and teachers, as writers and people with more than a few wrinkles by their eyes, let us do what is right by our young people. Let us not rewrite their stories. Let us not allow them to think that winning is more important than knowing. Let us remind them that honesty, authenticity, goodness is the ultimate aim, not stars or unearned privilege. Let them find out who they are.

When, for example, I asked my young people to create a character, I gave out no stars. When I served as the Master Writing Teacher at the National YoungArts Foundation a few years ago, I did not go to upgrade the students' work; I went to provoke them with new prompts, new readings, new conversations, to encourage them to dig deeper within their own souls. And at Penn, where I teach a single course once each year, I am not rewriting my students' work, not rewriting their essays. I am pressing them to take each idea and every line farther—for their own sake. I am rewarding hard work and careful thought. I am rewarding personal growth. I am disappointed by those who take short cuts. Because it only hurts them.

One last word on this. Lately I have been going through many boxes from my youth. Reading, with a terrible blush in my cheeks, my early poems. People, they were awful. They were worse than awful. They showed no promise.

But they were mine. Never rewritten, never edited, never smoothed out. It took time time time for me to find my own way, and I'm still struggling. Having never taken formal creative writing classes, having taught myself through the books I've read and the friends I've made, I may still be behind the curve, but I am me behind that curve.

Let the young be themselves. Their breakthroughs will have more meaning.

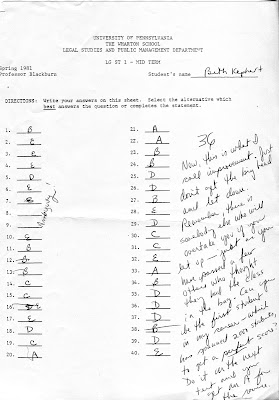

Reading through my old university files is akin to taking a graduate-level course in humility. How hard I tried—recopying notes, recopying the recopies. How overwhelmed I made myself by writing essays toward questions no one could ever really answer, by doing so much extra reading that I was drowning in the facts (and losing the essence). I was, it's clear, forcing myself toward a law degree as an undergrad. I was taking on extra projects at the Superior Court, writing papers on contract law, always looking for the legal angle in history papers and economics projects—and, most of the time, avoiding the fact that my passions lay elsewhere. I never took a single writing course at Penn. I only took one English course.

My professors wrote long notes to me. They bashed, they encouraged. They gave me early B's, cajoled me toward less baroque results, congratulated me when progress was made.

But none of it was easy. Most of the time, trying so hard, I was lonely. So lonely and ultimately out of my element that I left Penn for one semester to take classes at the much-smaller Haverford College. There (and I recall this well) I found my niche. There conversation mattered as much as the final exam.

Just now, sifting and sorting through these files, I find a note I wrote to a favorite Haverford professor. The final paragraph:

Finally, I'd like to add that, as a University of Pennsylvania student who moved off campus this semester feeling utterly alienated and unable to communicate with my contemporaries, the group discussion session proved extremely valuable to me. It was an experience as necessary as it was fun.

Perhaps I write today because I gave myself room for the poetic at Haverford. Perhaps much of the way I teach now at Penn stems from what I learned about the importance of creating classrooms where names are known, ideas are valued, and affection is absolute. We learn better in those environments. We take what we learned forward.

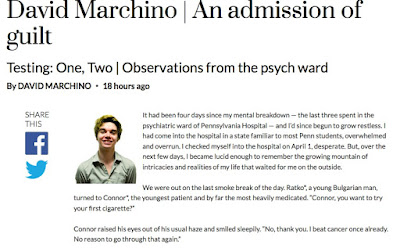

You know how I feel about my students. You know what love I had this past spring for My Spectaculars. Every. Single. Oneofthem. This young man—this David—was integral to us, remains integral to us, speaks truth, speaks it gently, and has something to say about mental wellness in this issue of

The Daily Pennsylvanian.David went missing for a class last spring. My students rallied to locate him. And while they did, I was having a conversation with myself and with those I trust about what universities can do for students who need time away from pressure. David articulates so masterfully here what students might do for one another. He is asking for a culture of mutual caring, of values that transcend the GPA, of a turn toward soul. I commend this. I believe that when you step onto a college campus you are making a commitment to loving watchfulness. Watch out for your friends. Watch out for your students. And may these harried students be given time—be given the resources—to take care of themselves.

David is about to set off for his first trip overseas. His first airplane ride. His first of many things. He's promised to update me on all he sees, but before he goes, please read his words.

Here.David, Godspeed and God bless.

How difficult it is becoming for all of us to get up and go about our daily work. As if the ground isn't shaking beneath us. As if terror and its isms haven't edged too close. As if the farmers don't need rain. As if it not snowing, in May, in Wyoming. As if our friends were not on that Amtrak train that rode a curve too hard outside our city.

What are we to do with the news? How are we to live our own lives, tick and tock after our own ideas, stand for this or stand for that, prepare our defenses despite the fact that there is no defense against earth grind, cruelty, the drought within our skies?

What is solid, standing, everpresent, ever true? What matters, and what can we do?

I woke up to write a proposal for the

2015-16 Beltran Family Event. To sneak a line or two of a

novel-in-progress onto the page. To get ready for the day's client interviews. To write the bills. The small, the daily, the mine, the one. Get up. Do it. Believe. But there, again, is the news.

6:10 now. The morning hours gone. Another day and in defense against the defenseless, I will pretty my garden, present a cake, send flowers to a friend, call my son and call my father. The things I still know how to do, in the face of too much news.

The last time Julia Bloch was on this blog

she was hosting Dorothy Allison at Kelly Writers House—leading a conversation through the wickets of time.

Yesterday I was privileged to see Julia, the newly named director of Penn's Creative Writing program (replacing Greg Djanikian, about whom I wrote

here), engage in conversation with KWH Fellow Jessica Hagedorn. Poet, playwright, novelist, teacher, creator of an MFA program, provocateur, sometimes-reluctant-and-sometimes-not-reluctant pundit, Hagedorn was as bright as the sun breaking in through the trees behind her. Funny, too. Easy to adore.

I listened with care, leaning in especially close when the talk turned to the Philippines, a land that lives in my husband's blood. I listened and thought of how privileged I am to work at Penn, within the KWH frame, where, thanks to this marvel that Al Filreis stirred into being (and Jessica Lowenthal so ably guides on a daily basis), so many remarkable voices, thinkers, makers arrive, suggest, and leave some shimmer dust behind. We are never done as teachers. We never know enough. We have something to gain by sitting and listening to those who have built great worlds with words.

I went off to be with My Spectaculars one final time (an image of them

here; oh, my heart). I came home with a lump in my throat and a copy of

Dogeaters, the first novel in a series of Hagedorn novels that I will read this summer.

we tried to stop the afternoon from ticking to a close.

we held on.

tight.

Yesterday Kelly and I walked Longwood Gardens where the tulips were like new crayons in tight boxes and the rose grapes hung from ceilings as if waiting to be pressed toward wine and the trees were actually flowers and the treehouse mirror turned us into a 17th century painting with 21st century iPhones. It was spring, crisp, crowded.

The hours served as punctuation. A period, perhaps a colon marking the end of a long winter of talks and workshops, essays and reviews, teaching and papers, intense client work and client revisions, the quiet launch of a novel and the heart-ish completion of a collection of essays. Tomorrow is my last class with the Spectaculars at Penn. We have worked hard together, grown together, hurt together, soared together, and on this day I sit reading their final work—the profiles they have written about people who matter to them. I believe that writing can serve no greater purpose than to awaken the writer to the world itself—the things that matter—and to, in that way, force love (or call it attention) onto the page. I believe that teaching craft is teaching soul. I believe in the quiet things that happen in the margins. I believe.

It's the kind of belief that won't make a person famous. The kind that simmers just off to the left, that urges with wet eyes, that suggests and does not demand, that says,

Maybe. The kind that is noticed by a few but rarely by many. Am I, I am asked often and ever more frequently, okay with that? Don't I, after all these quiet books, all these quiet years, all these words living in the shadows, want

more?

There are crayon tulips. There are decorated trees. There are steps leading up to the sky. There are moments. There are students. There are friends; there is family. There is a husband and a son. There are books on my shelves written by authors with far greater talent, wisdom, seeing, stretch—and I see that talent, I am grateful for that talent, I am instructed by it, happy for it, elevated and poem-ed by it.

This is my more. This is my life.

Discover the work of Benjy Brooke, Cartoon Brew's Artist of the Day.

Not long ago, while I was enthusing about my students to a friend, I was stopped by a gently lifted hand and a question: "But don't you

always love your students?"

But love, I wanted to say, is particular. Love is not an undifferentiated rush. Love happens

because. Because of who these young people are, because of the community they've built, because they are working proof of the power of unshackled hearts and vulnerability and the kind of imagination that becomes another way of saying

compassion. I love my students. I love

these students.

Last week, while posting

my HuffPo essay on My Spectaculars and their expectations regarding the memoirs they read, I promised that we would soon hear from Sarah Gelbard, my graduate student who slipped into our classroom as an auditor that first day and (we're so infinitely glad) stayed. A few Tuesdays ago, I asked Sarah, who works with the Friedreich Ataxia Program at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, to read to the class a piece she had written for

Arts Connect International, where she was recently named content editor. I've been eager, ever since, to share this complete essay with you, especially in light of, well, everything. Including

this.Here is how Sarah's piece begins:

Disability is dealt arbitrarily; it is not a welcome present. Nobody goes to the gift shop, and says, “Ankylosing spondylitis— that sounds lovely!” Or, “I’ll take a brachial plexus injury for my brother on his birthday, with the red wrapping paper, please, and a free sampling of multiple sclerosis for me.” While I did not choose cerebral palsy, I do consider myself lucky to be a part of the disabled community. Through it, I have forged valuable connections with a great many, and we are allowed singular insight into the broad spectrum of human empathy. We encounter those who judge harshly, cruelly, fast to reject apparent otherness, and those who reach out seamlessly, kindly, fast to recognize apparent humanness.

Here is how it continues. Please read this. Please share it. It matters. So does Sarah.

Readers of

Handling the Truth: On the Writing of Memoir know that—while I greatly vary the way I teach, the books I share, and the writers I invite to the classroom—there is one consistent essay I assign early-ish in the teaching season. A 750-word response designed to shake out ideas, ideals, and possibilities.

This year My Spectaculars produced such extraordinarily charming and elucidating responses to the assignment that I decided (with my students' permission) to knit together elements so that we might always have a record of Us. I've called the piece "How to Write a Memoir. Or (The Expectations Virtues)" and shared it on Huffington Post.

The piece, which begins like this, can be found in its entirety

here. I call them My Spectaculars. Together, we read, we write. We rive our hearts. We leave faux at the door. We expect big things from one another, from the memoirists we read, from the memoirists who may be writing now, from those books of truth in progress.

But what do we mean by that word, expectation?

It's a question I require my University of Pennsylvania Creative Nonfiction students to answer. A conversation we very deliberately have. What do you expect of the writers you read, and what do you expect of yourselves?

This year, again, I have been chastened, made breathless, by the rigor and transparency of my most glorious clan. By Anthony, for example, who declares up front, no segue: ......

(Read on, I exhort you. Find out.)

There is a single student voice missing from this tapestry—my Sarah. You are going to be hearing from her next week or so, after a page or two of her brilliance is published and cross-linked here. Trust me, you will be changed by Sarah's words.

For now, I leave you my students. Read, and you'll call them Spectaculars, too.

View Next 25 Posts