By Duncan Calow

It is only March, but 2012 has already seen a series of contract disputes over digital media and technology hit the headlines.

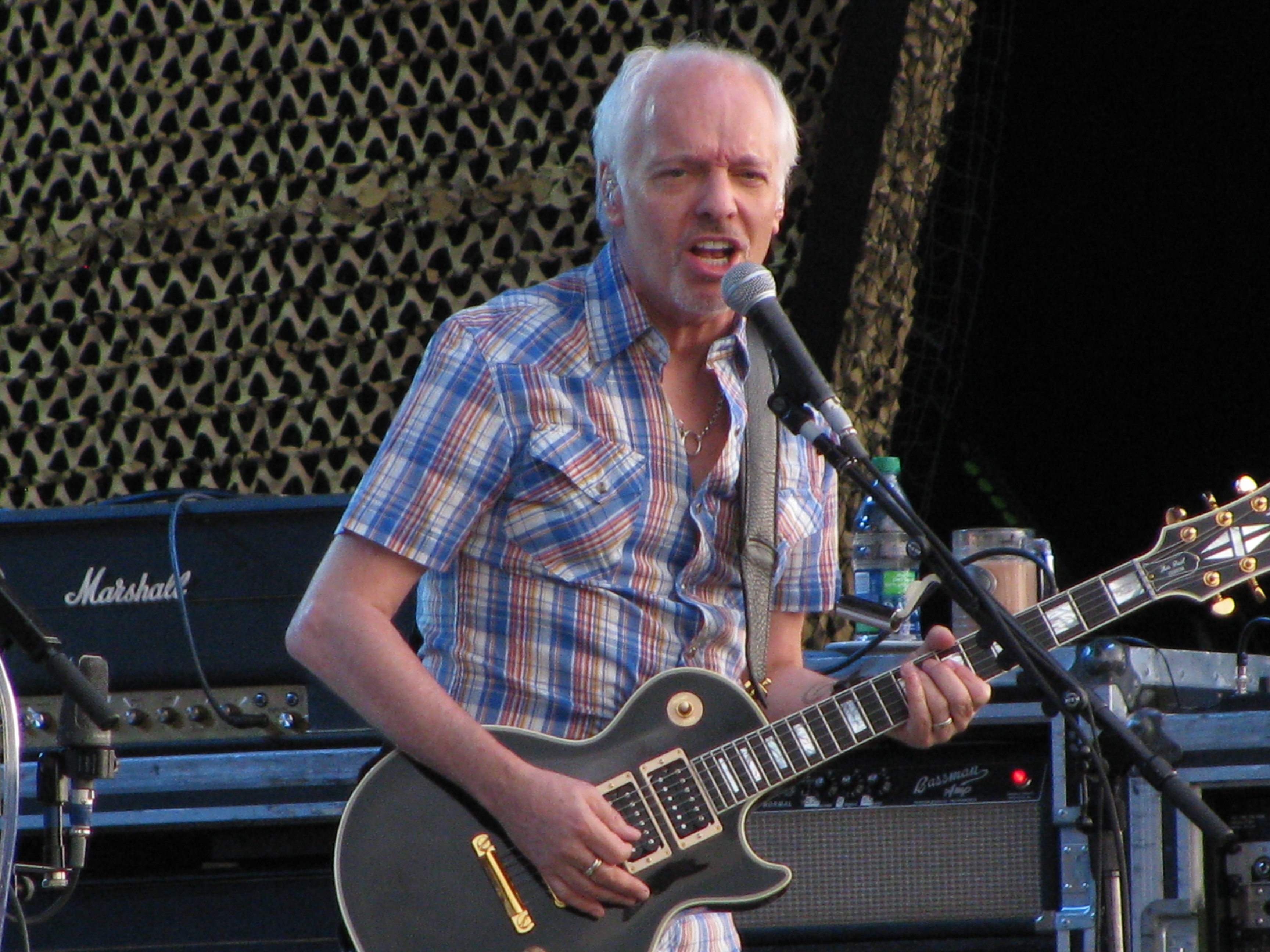

First, rock star Peter Frampton announced he had filed a lawsuit against his record label for half a million pounds worth of unpaid music royalties and other damages. Frampton claimed he was contracted with A&M Records to receive a 50% royalty for the use of “licensed” music but had not received payment on any digital sales.

Then there was news that book publisher HarperCollins had filed a lawsuit against digital publisher Open Road for copyright infringement in relation to e-versions of the children’s book, “Julie of the Wolves”. HarperCollins claims its author contract gave it the exclusive ability to publish the work in any format but Open Road claims to have been granted the e-book rights.

And even ‘new media’ companies have their problems too. PhoneDog.com, an interactive mobile news and review website, was reported to have sued a former employee for £217,000 after he converted a Twitter account, which it was claimed was originally set up on behalf of the employer, for his own use after leaving the company.

Each of the cases involve very different parties with very different facts and very different contracts.

The first is just one of many cases over how revenue in sales of digital music should be split between artists and labels, often with a focus on how physical distribution terms can apply to digital delivery. The second case raises, once again, the crucial question over how far fundamental expectations within a contract about how a work can be exploited can change as technology develops. The final dispute highlights the need for all businesses to keep employment contract and policies up to date to reflect the way in which social media and other technology is adopted in the workplace.

It remains to be seen how successful any of the claims will be as the full circumstances of these cases emerge over time or as the parties reach settlements.

What is clear, however, is that keeping contractual arrangements up-to-date with an ever evolving media and technology landscape continues to be a challenge. It is also a form of challenge that existed well before digital. Legal text books recount the disputes that arose as theatre plays were first filmed for cinema – or when cinema films were first shown on television and released on video.

The pace of change is of course faster now and the inherent nature of digital technology allows greater opportunities for re-use. Accordingly, it is commonly suggested that the best solution is to work with technology-neutral contracts that reflect a ‘converged’ digital media. Yet in practice there is often still a need to main sector specifics and capture particular technical details.

In fact, dealing with digital successfully in a contract is often a balancing act between maintaining familiar structures and form alongside sufficient further foresight and flexibility. Future developments may not always be predictable but contracts can still try to provide for that uncertainty.

Meanwhile, it’s a pretty s