new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: ale, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: ale in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Flavouring Fantasy

by Chantal Boudreau

Food isn’t necessarily the first thing that you think of when you think of fantasy... or the second thing... or the third or fourth thing. In fact, superseded by monsters and magic, warriors and weapons, it may be ignored altogether in the typical fantasy novel.

Understandably, food isn’t likely to play an integral role in the usual fantasy plot, which is why there is little focus placed on what and how things are eaten in many fantasy stories. But considering world-building is the cornerstone of fantasy fiction, and food is often a factor of ceremony, culture and social interactions, it makes sense that the concept of who tends to eat what and when be addressed as part of the backdrop of the tale. Fantasy writers often describe religions, political systems, architecture and flora and fauna. Food is just another way of flavouring the fiction.

This can be an especially useful tool if the fantasy in question is based on existing myths or cultures, as a means of highlighting this connection. For example, if the fantasy touches on the Middle East, one might expect to see figs, goat cheese and falafel, or if it is a northern tale, the writer might have characters feasting on seal or caribou meat (or the fantasy equivalent.) In my novel Magic University, which finds its basis in medieval Europe as is common to many fantasy novels, the typical fare is ale, bread, smoked meats and cheese, and fruits or vegetables one could expect to see growing in the average European garden.

Researching this component of a story is not that difficult in today’s day and age. You can even find books that specifically discuss what might be eaten in a fantasy setting, such as What Kings Ate and Wizards Drank by Krista D. Ball. There are also cookbooks available that are based on existing fantasy series, such as Leaves from the Inn of the Last Home (Otik’s spicy fried potatoes is a favourite of mine) based on the Dragonlance series or Nanny Ogg’s Cookbookbased on the Discworld series, just to give you a few ideas.

It also makes sense to include examples of food and drink as part of both plot and character development, giving the writer another means to an end. For example, in the opening scene of Magic University (the first book in my Masters and Renegades fantasy series), there is a small skirmish between Reid Blake’s imp, Stiggle and the dwarven competitor, Shetland, which is instigated by food. The function of the scene is two-fold. It creates a tension between Stiggle and Shetland that persists throughout the novel, allowing for later scenes of discord that exist mostly for comic relief. It also introduces Shetland’s obsession with food and drink, part of his character development which shows itself again several times in the story.

Food can be used to distinguish one setting from another, as well. A grubby pub for commoners will have very different items on the menu than an upscale tavern intended for higher-class patrons. Along with a description of decor and existing customers, a description of the food and drink being offered and served can help set the tone of the establishment. In Magic University, each competition Way Station is being hosted by a different wizard, who provides refreshments that match their personality. The variety of food and drink found at each Way Station not only tells readers something about the Way Station attendant, but also adds to the particular ambiance of the Way Station.

Along with general plot and character development, food can also provide an opportunity to flush out the more unusual plot elements and distinct characters. A fantasy novel may contain characters with very particular feeding needs, something that adds to the novelty and fantastical nature of that character. One of my characters in Magic University, Ebon, is a person who exists trapped between two dimensions due to an accident that occurred when he was apprenticed to a Renegade wizard. Rather than feeding the way most people do, he draws his sustenance from magical energies, draining power from magical spells or items in the process. As he puts it: “I still appreciate a good meal, on a purely aesthetical level. It is just something that is unnecessary. I draw my energy from other sources.” I even include one scene where his feeding needs interfere with his goals.

As you can see, there are many reasons a fantasy writer would want to incorporate food into a story. If you’ve never really contemplated the role food can and does play in well-written fantasy, you may want to give it a go. Consider it food for thought.Thanks for stopping by to share your food for thought, Chantal!

Chantal Boudreau is an accountant/author/illustrator who lives in Nova Scotia, Canada with her husband and two children. A member of the Horror Writers Association, she writes and illustrates horror, dark fantasy and fantasy and has had several of her stories published in a variety of horror anthologies and magazines. Fervor, her debut dystopian novel, was released in March of 2011 by May December Publications, followed by Elevation, Transcendence, and Providence. Magic University, the first in her fantasy series, Masters & Renegades, made its appearance in September 2011 followed by Casualties of War and Prisoners of Fate.You can find Chantal and her books here:

By: Lana,

on 12/1/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

beer,

Food & Drink,

Wine,

ale,

garrett oliver,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

holiday party,

oxford companion to beer,

christmas ale,

ales,

doppelbock,

eggenberg,

histories—notably,

Christmas,

Add a tag

Oxford staffers Stephanie Porter, Tara Kennedy, and Lana Goldsmith are here to show you how to pair beer with cheer as we enter the holiday season. Below is the first of our posts that will be featured every Thursday this month.

Now that the calendar has turned the page to December, holiday season is in full swing. Aside from the lights and decorations flooding streets and buildings everywhere, this is the season of holiday parties! We will be celebrating The Oxford Companion to Beer through the month of December, and to kick off the month, we are turning our attention to hosting a holiday beer tasting.

First, a brief overview of the season’s beer history about the special brews available this season from contributor Chris J. Marchbanks.

Christmas ales is a catch-all descriptive phrase given to special beers made for Christmas and New Year celebrations, often with a high alcohol content 5.5%–14% ABV and marked by the inclusion of dark flavored malts, spices, herbs, and fruits in the recipe. A medieval instance of a Christmas ale was called “lambswool”—made with roasted apples, nutmegs, ginger, and sugar (honey)—so-called because of the froth floating on the surface. Today’s versions tend to be based on old ale, strong ale, and barley wine recipes, using cinnamon, cumin, orange, lemon, coriander, honey, etc. to create a warming, dark, and luscious festive beer. See old ales and barley wine. This tradition is closely related with the “wassail”, a mulled wine, beer, or cider usually consumed while caroling or gathering for the Christmas season. Most country breweries produce a Christmas or seasonal ale, some with long histories—notably in Belgium, England, Scandinavia, and the United States—which are usually matured for many months. There is no fixed recipe for these special ales as it is an opportunity for the brewer to expand boundaries and explore new tasty ingredients for Christmas, as the brewer’s gift to yuletide. The category includes some of the strongest beers brewed in the world including Samiclaus, which is a rich, aged Doppelbock with 14% ABV, originally brewed by Hurlimann in Switzerland but now in Austria at the Eggenberg Brewery. In the United States, Christmas Ale at Anchor Brewing (also known as “Our Special Ale”) contains a different blend of spices every year and helped spawn an interest in Christmas ales in the early days of the craft beer movement.

Since beer can have a cornucopia of flavors in every glass, you and your guests talk about the subtleties of each different beer. I might play a matching game where everyone writes down what they taste, and then the host can read the flavors from the label; or steam the labels off and have each person guess which label goes with which beer based on design. Either way, you will want to know how to create the perfect pour, and luckily, we know just the man to show you.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Now that you have the pour down, what can you serve your beer in? It turns out that beer glassware has a long history, and the glass you serve it in matters. Take a quick tour of some of the elaborate glasses beer used to be served in, and grab some ideas of what will best suit your chosen suds.

Click here to view the embedded video.

You may not be an expert, but you are definitely ready to pepper your guests with a little beer wisdom. So have fun, b

By: Lauren,

on 3/9/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

beer,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

Food & Drink,

anatoly liberman,

drinking,

mead,

ale,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

shandy,

Shandygaff,

smiler,

Add a tag

In March 2006, Anatoly Liberman joined OUPblog, “living in sin” as the Oxford Etymologist. Every Wednesday for the past five years he has delighted us with theories, research, and amusing anecdotes about words and language, and today we celebrate with beer! Professor Liberman, we raise our glasses to you. Cheers! Long live the Oxford Etymologist!

I’m raffling off a free copy of Word Origins to celebrate. If you’d like to enter, just leave a comment, sharing your favorite Oxford Etymologist post and why. While you’re at it, feel free to ask the professor a question. The winner will be contacted early next week.

By Anatoly Liberman

At the beginning of the previous post, I promised to say more about some strange names of beverages. The time has come to make good on my promise. In a note dated December 1892, we can read the following: “Shandygaff is the name of a mixture of beer and ginger-beer…, and according to evidence given at the recent trial of the East Manchester election petition, a mixture of bitter beer and lemonade is in Manchester called a smiler.” Shandygaff and especially its shortened form shandy are still well-known words (like smiler, shandy can also contain lemonade), but it would be interesting to hear from Manchester whether smiler is still current there. The older the word, the more respect it inspires in us, and we forget that language has always flourished on the rich garbage of human communication, which includes jokes, slang, and all kinds of word games. Scholars make desperate efforts to find Hittite, Greek, and Germanic roots preserved in the most ancient form of ale, while it may have been some funny coinage like shandygaff or smiler. Although etymologists exist to remove the accumulation of dust from modern vocabulary, they needn’t treat every speck of that dust as a sacred relic.

To remind modern readers that in England ale never had the ceremonial glamour associated with it in medieval Scandinavia, I would like to call their attention to the obsolete (thank heavens, obsolete) word ale-dagger “a weapon used in alehouse brawls.” Here is a passage from Sir John Smythe’s 1590 Certen Discourses concerning Weapons. I will retain the orthography of the original (the words, like certen in the title, are easy to recognize): “Long heavie daggers also, with great brauling Ale-house hilts (which were never used but for private fraies and brauules, and within lesse than these fortie yeres), they doo no waies disallow.” Good grief! Heavy daggers with great hilts, designed for the purpose of settling private disputes were “in no way” disallowed! Speak of the Second Amendment and the right of an individual to bear firearms for self-defence! In the middle of the 16th century “citizens” did not carry guns in pubs and had to look, speak, and use only daggers. Primitive, backward people. Brawls in alehouses were already mentioned in Old English laws. Human behavior changes slowly, if at all.

After so much etymological ale, we can now tackle beer. Unlike ale, recorded in all the Old Germanic languages except Gothic, beer is at present a West Germanic word (German, English, Dutch, etc.). Its Old Scandinavian cognate is usually believed to be a borrowing from Old English; yet no decisive arguments have been adduced in support of this i

By: Lauren,

on 3/2/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Food and Drink,

language,

beer,

Oxford Etymologist,

German,

alcohol,

word origins,

Greek,

etymology,

vodka,

arabic,

anatoly liberman,

drinking,

Scandinavian,

word history,

ale,

*Featured,

notes and queries,

Lexicography & Language,

black and tan,

hittite,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

The surprising thing about the runic alu (on which see the last January post), the probable etymon of ale, is its shortness. The protoform was a bit longer and had t after u, but the missing part contributed nothing to the word’s meaning. To show how unpredictable the name of a drink may be (before we get back to ale), I’ll quote a passage from Ralph Thomas’s letter to Notes and Queries for 1897 (Series 8, volume XII, p. 506). It is about the word fives, as in a pint of fives, which means “…‘four ale’ and ‘six ale’ mixed, that is, ale at fourpence a quart and sixpence a quart. Here is another: ‘Black and tan.’ This is stout and mild mixed. Again, ‘A glass of mother-in-law’ is old ale and bitter mixed.” Think of an etymologist who will try to decipher this gibberish in two thousand years! We are puzzled even a hundred years later.

Prior to becoming a drink endowed with religious significance, ale was presumably just a beverage, and its name must have been transparent to those who called it alu, but we observe it in wonder. On the other hand, some seemingly clear names of alcoholic drinks may also pose problems. Thus, Russian vodka, which originally designated a medicinal concoction of several herbs, consists of vod-, the diminutive suffix k, and the feminine ending a. Vod- means “water,” but vodka cannot be understood as “little water”! The ingenious conjectures on the development of this word, including an attempt to dissociate vodka from voda “water,” will not delay us here. The example only shows that some of the more obvious words belonging to the semantic sphere of ale may at times turn into stumbling blocks. More about the same subject next week.

Hypotheses on the etymology of ale go in several directions. According to one, ale is related to Greek aluein “to wander, to be distraught.” The Greek root alu- can be seen in hallucination, which came to English from Latin. The suggested connection looks tenuous, and one expects a Germanic cognate of such a widespread Germanic word. Also, it does not seem that intoxicating beverages are ever named for the deleterious effect they make. A similar etymology refers ale to a Hittite noun alwanzatar “witchcraft, magic, spell,” which in turn can be akin to Greek aluein. More likely, however, ale did not get its name in a religious context, and I would like to refer to the law I have formulated for myself: a word of obscure etymology should never be used to elucidate another obscure word. Hittite is an ancient Indo-European language once spoken in Asia Minor. It has been dead for millennia. Some Hittite and Germanic words are related, but alwanzatar is a technical term of unknown origin and thus should be left out of consideration in the present context. The most often cited etymology (it can be found in many dictionaries) ties ale to Latin alumen “alum,” with the root of both being allegedly alu- “bitter.” Apart from some serious phonetic difficulties this reconstruction entails, here too we would prefer to find related forms closer to home (though Latin-Germanic correspondences are much more numerous than those between Germanic and Hittite), and once again we face an opaque technical term, this time in Latin.

Equally far-fetched are the attempts to connect ale with Greek alke “defence” and Old Germanic alhs “temple.” The first connection might work if alke were not Greek. I am sorry

By: Lauren,

on 2/16/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Poetry,

Literature,

Food and Drink,

myths,

Religion,

beowulf,

Oxford Etymologist,

anatoly liberman,

drinking,

ibsen,

ale,

Germanic,

nordic,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

grieg,

poetic edda,

word origins,

word history,

scandanavian,

teutons,

veig,

lith,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

English lacks a convenient word for “ancestors of Germanic speaking people.” Teutons, an obsolete English gloss for German Germanen, is hardly ever used today. The adjective Germanic has wide currency, and, when pressed for the noun, some people translate Germanen as “Germans” (not a good solution). I needed this introduction as an apology for asking the question: “What did the ancient Teutons drink?” The “wine card” contained many items, for, as usual, not everybody drank the same, and different occasions called for different beverages and required different states of intoxication, or rather inebriation, for being drunk did not stigmatize the drinker. On the contrary, it allowed him (nothing is known about her in such circumstances) to reach the state of ecstasy. Oaths sworn “under the influence” were not only honored: if anything, they carried more weight than those sworn by calculating, sober people. Many shrewd rulers used this situation to their advantage, filled guests with especially strong homebrew, and offered toasts that could not be refused.

In the mythology of the Indo-European peoples a distinction was made between the language of the mortals and the language of the gods, a synonym game, to be sure, but a game fraught with deep religious significance. The myths of the Anglo-Saxons and Germans have not come down to us, but the myths of the Scandinavians have, and in one of the songs of the Poetic Edda (a collection of mythological and heroic tales) we read that the humans call a certain drink öl, while the Vanir call it veig (the Vanir were one of the two clans of the Scandinavian gods). Öl is, of course, ale, but veig is a mystery. No secure cognates of this word have been attested, and the choice among its homonyms (“strength,” “lady,” and “gold”) leaves us with several possibilities. Identifying “strong drink” with “strength” sounds inviting, but who has heard of an old alcoholic beverage simply called “strength”? Veig- is a common second element in women’s names, of which the English speaking world has retained the memory of at least one, Solveig, either Per Gynt’s true love in Ibsen and Grieg or somebody’s next door neighbor (I live in a state settled by German and Scandinavian immigrants, so to me Solveig is a household word, quite independent of Norwegian literature and music). It is hard to decide which -veig entered into those names. “Gold” cannot be ruled out. On the other hand, it was a woman’s duty to pour wine at feasts, so that -veig “drink” would also make sense. In any case, veig remains the name of a divine drink of the medieval Scandinavians. It stands at the bottom of our card.

From books in the Old Germanic languages we know about the Teutons’ wine, mead, beer, ale, and lith ~ lid, the latter with the vowel of Modern Engl. ee. Lith must have corresponded to cider (cider is an alteration of ecclesiastical Greek ~ Medieval Latin sicera ~ cicera, a word taken over from Hebrew). It was undoubtedly a strong drink, inasmuch as, according to the prophesy in the oldest versions of the Germanic Bible, John the Baptist was not to taste either wine or lith. The word is now lost, and so are its origins. Mead is still a familiar poeticism, while the other three have survived, though, as we will see, beer does not refer to the same product as it did in the days of the Anglo-Saxons—an important consideration, because the taste of a beve

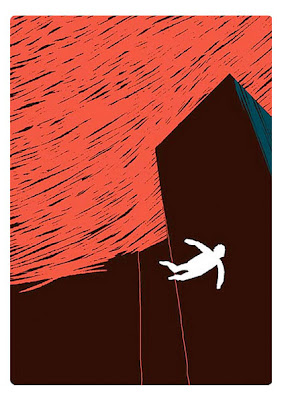

There's an edge to

Alé Mercado's illustrations. His work conveys emotion through gritty texture, aggressive, bold line-work and uncluttered, well-organized page structures. Some of his work is reminiscent of Edvard Munch and the Expressionist prints of Kirchner and Pechstein.

Alé is also no stranger to typography. In some of his work he incorporates different typefaces that compliment his illustrations nicely. And Alé uses color sparingly, which is another element that adds to the atmosphere and intensity of his work.

Alé's Facebook page displays a good amount of his designs and illustrations. He also incorporated an

Events tab which offers a list of upcoming events.

Fantastic Ale! No less than u deserve.