Day 14

Topic - torso structure and leg musculature

A working knowledge of anatomy will give any illustrator a solid foundation upon which to hone one’s drawing skills. The possibilities are infinite, as along as you begin with the basic skills first.

A working knowledge of anatomy will give any illustrator a solid foundation upon which to hone one’s drawing skills. The possibilities are infinite, as along as you begin with the basic skills first.

Case-in-point: Check out this interview with multi-talented artist Edel Rodriguez here. Then check out his portfolios and blog here.

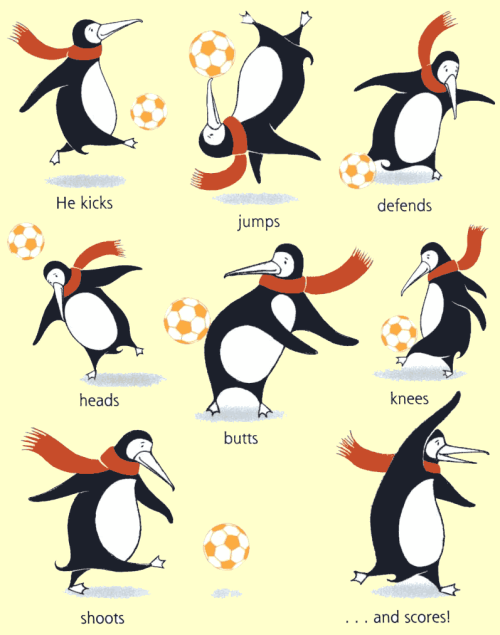

Note the variety of moves he applies to his character, Sergio, a penguin who loves soccer!

All illustrations © Edel Rodriguez

All illustrations © Edel Rodriguez

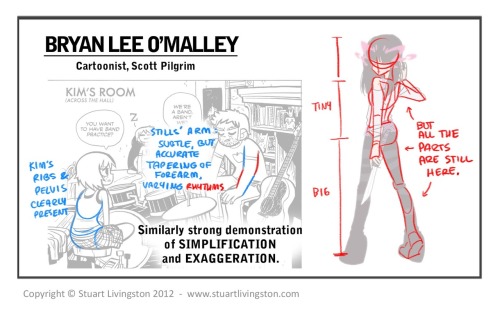

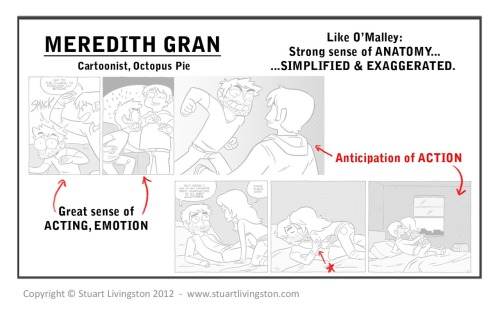

A nice person teaching at CalArts did an anatomy lesson and included examples from me and Meredith Gran and others.

See, I … I know what i’m… i’m … doing….

http://stulivingston.blogspot.com/2012/10/life-drawing-for-animation-demoz.html

We are in a golden age of comics and cartoonists being embraced by smart people in academia. To those learning comics now as young people, enjoy this privilege that no other generation before yours has enjoyed!

I just love these brilliant Anatomical Nesting Dolls by Stuntkid, illustrator Jason Levesque.

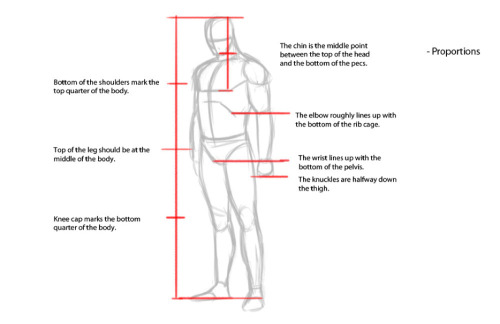

Anatomy Lessons from Kris Anka

Kris Anka offers up a series of anatomy pointers on his blog, Design Lessons.

I decided to take some time to scan a few things from my sketchbooks so far this year.

Some are studies of anatomy I made from “Anatomy and Drawing” by Victor Perard, some are studies from a book about animation and other’s are studies of animals and also various things from my head.

I’m just going to lump them all here as a gallery.

Cartoonist and Dreamworks storyboard artist Rad Sechrist has a how-to blog, rich with drawing tips, anatomy lessons, and and other bits of wisdom. It’s a fantastic resource, and I’ve already bookmarked it for future visits. Link: Rad How To

Posted by John Martz on Drawn! The Illustration and Cartooning Blog |

Permalink |

One comment

Tags: anatomy, Drawing, How-To, Resources, storyboards

iTunes users can subscribe to this podcast ![]()

The first English bastard appeared in 1297, although you can be sure people were born out of wedlock before that.

Today people get called bastards all the time without reference to their parents’ state of marriage, and increasingly people are being born of non-married couples and find it offensive to be called bastards.

Around the time when bastard first appeared in English William the Conqueror was known also as William the Bastard. This isn’t because he was a dirty rotten conqueror—the word bastard hadn’t taken on its insulting meaning yet—he was William the Bastard because his parents hadn’t been married.

Having babies out of wedlock has until very recently been something to be terribly ashamed of and downright impractical. So it makes sense that bastard has been used as an insult for some time, but it only made it into print as an insult in 1830.

The root of the word is from Old French and grew out of bast, the name for a packsaddle, which was the structure used to load packs onto a mule. Travelers with romantic intention and opportunity may not have had a convenient bed nearby so the blankets and saddle would serve as bedding and pillow.

The root of the word is from Old French and grew out of bast, the name for a packsaddle, which was the structure used to load packs onto a mule. Travelers with romantic intention and opportunity may not have had a convenient bed nearby so the blankets and saddle would serve as bedding and pillow.

Thus children who were not conceived in the marriage bed, were said to be conceived “on the bast” and were therefore bastards.

At least that’s what the Oxford English Dictionary says.

But there, the entry for bastard is perhaps not the most up-to-date. This word has not yet received the repeat scrutiny of the third edition now in progress.

As such the citations given there for bastard are mostly more than a century old.

Other fresher dictionary etymologies decry this pack-saddle theory, saying the chronology of appearance of the supposed source and resulting words are wrong. A better guess (they say) might be a Germanic source word bost meaning “marriage” and that somehow bastards relate to offspring from polygamous marriages.

This is a case where accuracy and advancement of research has struck a blow against entertainment value.

iTunes users can subscribe to this podcast ![]()

If you remember that slapstick comedy duo Laurel and Hardy, you may remember Ollie’s standard line

“another nice mess you’ve gotten me into.”

Stan Laurel was the thin one and Oliver Hardy was the fat one.

This might bespeak a larger appetite on the part of Oliver Hardy and if so there might be an etymological explanation for Ollie’s quote.

Around the year 1300 the word mess made its first appearance in writing in English. This date points to a possible source of the word from French since it’s within a few hundred years of the Norman Conquest and it would have taken a few centuries for a French word to have been first picked up and adopted into English, and then eventually to find its way onto paper.

Sure enough the Oxford English Dictionary traces mess back to Anglo-Norman and Old French before that.

But what a hungry Oliver Hardy might have found interesting about a mess of 700 years ago is that it didn’t mean “a spot of trouble” as he might have meant in reprimanding Stanley, at first a mess was a serving of food, a meal.

But what a hungry Oliver Hardy might have found interesting about a mess of 700 years ago is that it didn’t mean “a spot of trouble” as he might have meant in reprimanding Stanley, at first a mess was a serving of food, a meal.

This connection between the word mess and food is preserved for us in the military where soldiers, sailors and pilots eat in the mess.

As with most French words mess actually goes back to Latin and the OED even takes it back further to Indo-European.

Back those five thousand years or more the Indo-European root mittere meant “to send” and the idea here is that the food was sent to the table. So from Indo-European to Latin the meaning was “to send” but while in Latin a meaning of “food” evolved that was carried into languages including French and Italian.

English adopted the “food” meaning but English was the only language to mutate the meaning again into our current meaning of “disorderly,” “untidy,” “cluttered” or “dirty.”

Here’s how that worked:

After that first appearance in 1300 the word mess changed its meanings in English a little bit. In one case it went from meaning “a meal” to meaning “a single portion.”

In another case it went from meaning “a meal” to meaning a specific kind of meal, something soft, liquid or goopy; porridge or soup would have been called mess by some people as early as 1330.

This is the meaning that matters to us because it is this mixed-up-stew kind of meal that gave rise to a meaning of mess by 1738 as feed for an animal and by 1828 as an unappetizing mixture of foods. Somewhere about this time the undesirable state of “things mixed together” lent the word mess to applications outside of the world of food.

The OED’s first citation for mess meaning “a predicament” or “troubling state of affairs” is from 1812. So by the time Stan and Ollie were getting into messes in the 1930s the principal meaning of “food” had been somewhat obsolete for a century or so.

iTunes users can subscribe to this podcast ![]()

According to John Ayto’s A to Z of Food and Drink:

According to John Ayto’s A to Z of Food and Drink:

“These new-moon-shaped puff-pastry rolls seem first to have been introduced to British and American breakfast tables towards the end of the nineteenth century.”

He goes on to cast aspersions on the stories told about the invention of these yummy baked goods. Wikipedia disses the stories too.

I’ll tell that tale in a moment, but I want first to point out that Ayto accurately called croissants new-moon-shaped.

John Ayto has written several books about words and their origins and so I’m sure that he chose his words there very carefully.

Of course we call that shape of moon a crescent moon and of course the words crescent and croissant are really two flavors of the same word; crescent arriving in English from French in the 1300s and croissant along with the pastry in at the end of the 1800s, also from French.

But when I refer to a crescent moon I’m usually just intending to communicate its fingernail-clipping shape. It could just as easily be a waning moon as a waxing moon.

But when I refer to a crescent moon I’m usually just intending to communicate its fingernail-clipping shape. It could just as easily be a waning moon as a waxing moon.

But new-moon-shaped refers only to waxing, or growing moons, and this is as is should be because the very word crescent has an etymology related to the growing moon.

A new moon begins with a very thin sliver of a crescent that grows and grows until it’s a full moon. It’s that growing we’re looking for.

I mentioned in the podictionary episode on recruit that an Indo-European root ker meant to grow. This same root turns up as crescere in Latin and was then applied to the growing moon. The shape thus took its name from this horned appearance of the moon.

This same shape is an Islamic symbol and the much discredited story of the invention of the edible croissant is tied to this Islamic crescent.

Supposedly the bakers in either Vienna or Budapest were up early one morning going at it with their bread dough and stoking up their ovens when they heard a digging noise.

They alerted the army who then prevented the Turks from entering the city by tunneling under the city walls. As a reward the bakers were allowed to, or asked to create celebratory goodies in the shape of the Islamic crescent.

Trouble is that these Turkish attacks happened back around the end of the 1600s and the first reference we have to the pastries doesn’t come until something like 170 years later. The first time the word was used in English was in 1899 according to the Oxford English Dictionary.

The user was a small time author from Alabama named William Chambers Morrow. He used it pretty enthusiastically too since it appears three times in his book about how students lived in Paris 100 and some-odd years ago.

But this use of croissant for the delicacy didn’t mean that was the first time English speakers were experiencing them. Crescent rolls are cited as an Americanism 13 years before.

iTunes users can subscribe to this podcast ![]()

Outside my window there stands an oak tree. I’d rather watch birds but sometimes I’m entertained by the antics of squirrels.

Outside my window there stands an oak tree. I’d rather watch birds but sometimes I’m entertained by the antics of squirrels.

For some reason most of the squirrels here in my town are black. Head out of town and they are red or brown and smaller. Where I grew up they were all grey.

But they all have one thing in common, a big bushy tail. In fact the entire species in named for it’s tail.

But they all have one thing in common, a big bushy tail. In fact the entire species in named for it’s tail.

As often as not these little rodents are using my oak tree for a highway moving from a garage nearby to a pine tree next door. In so doing they fearlessly fling themselves into the air and catch onto a branch of the tree they are landing in.

I had always assumed that the reason a squirrel had a big bushy tail was that as they careened through the space between branches they used it to wave around and keep from tumbling out of control. And they do, I’ve seen them enough times to know.

I had always assumed that the reason a squirrel had a big bushy tail was that as they careened through the space between branches they used it to wave around and keep from tumbling out of control. And they do, I’ve seen them enough times to know.

I did a little web searching and found one site that claimed a squirrel uses its tail to communicate. That makes sense, my dog uses her tail to communicate too and it’s certainly true that we humans have various body parts evolved for one purpose and used as communication tools as well.

Think of people who wave their hands around when the talk. More to the point think of your eyebrows designed to keep dust and rain out of your eyes but very useful in sending signals to other people.

But last year I heard of a study of squirrels using their tails in a completely different way.

Rattle snakes like to eat squirrels and because rattle snakes are equipped with heat sensing organs to help them hunt, squirrels that live in the same environment as rattle snakes have evolved an ability to heat up their tails when confronted by a snake so that when the snake strikes it tends to misfire toward the hotter tail and miss the main meal.

These are ground squirrels so their tails aren’t quite so bushy.

Squirrels in South Africa have also been studied and found to be using their tails in another temperature related way.

These guys hang their bushy bottle brushes overhead like some kind of parasol to keep the sun off. The study found that tail shading in sunny 40ºC heat allowed the little tree rats to drop their body temperatures to 35 ºC and extend their nut hiding to a full 7 hour day.

These guys hang their bushy bottle brushes overhead like some kind of parasol to keep the sun off. The study found that tail shading in sunny 40ºC heat allowed the little tree rats to drop their body temperatures to 35 ºC and extend their nut hiding to a full 7 hour day.

Overheated rodents knocked off after only 3 hours.

And believe it or not this is exactly why a squirrel is called a squirrel.

When the French invaders arrived in England in 1066 the Anglos were calling the things aquerne. But the French soon changed that to esquirel which they had gotten from Latin.

The Romans before them had chosen their word because the Greeks before them had used skiouros to describe these little rascals.

In Greek skiouros means “shade tail.” In fact the uros part is related to our English word arse.

It’s worth touching on that Old English word for squirrel aquerne.

It, as most Old English words, came from Germanic and like the modern German word for squirrel essentially means “oak horn.” No one knows why these little guys might be called horns, but the oak part is obvious enough, I can see it through my window.

Happy birthday to my wonderful, brilliant sister who got the best birthday present last night: a ring. So for months...MONTHS...my sister-in-law and I have been waiting, waiting, waiting, for some *news* from my sister regarding a ring (yes, my sister too has been waiting I'm sure). We just knew it would happen, but not when. I thought for sure something would happen in August, which is their

This blog is gold! Thank you.

great

Nice simple explanations and views of anatomy. great stuff.

I just love that his name is Rad.

Amazing drawings and incredible knowledge shared! Thank you very much!

a beautiful reference, thanks!