new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: book selection, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: book selection in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

hannahehrlich,

on 3/8/2016

Blog:

The Open Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

multicultural books,

amazing places,

book selection,

Educator Resources,

diverse books,

Diversity, Race, and Representation,

Guest Blogger Post,

Diversity 102,

sunday shopping,

maya's blanket,

Add a tag

Today we are pleased to share this guest post from L ibrarian and Diversity Coordinator Laura Reiko Simeon. Welcome, Laura!

ibrarian and Diversity Coordinator Laura Reiko Simeon. Welcome, Laura!

On a shuttle bus at the ALA Midwinter Conference, I overheard a conversation between two librarians who had also attended the event where Journey around Our National Parks from A to Z by Martha Day Zschock (Commonwealth Editions, 2016) was showcased as an example of inclusivity, portraying as it does ethnically diverse individuals enjoying the great outdoors. I was disturbed to hear these white women chuckling over what they saw as the ridiculousness of this book’s presentation in a session about diversity. They made it clear through snorts of derision that just having pictures of children of color didn’t count as making a book diverse, and that the effort itself to show diversity in this book was just plain silly.

Later, I couldn’t stop thinking about this. Zschock’s illustrations are important topically, as the New York Times piece, “Why Are Our Parks So White?” makes clear. Showing a dream for the future of these precious spaces is no small thing. But Zschock’s choice to include only visual diversity also has broader significance as Christopher Myers wrote in “The Apartheid of Children’s Literature”:

Children of color remain outside the boundaries of imagination. The cartography we create with this literature is flawed.

A book alone may not literally bring a child of color into a National Park, but it can plant a seed that may one day bear fruit. For a child to see someone who looks like them enjoying nature amidst a sea of books that show absolutely no one like them doing any such thing – to me that is most definitely not laughable.

White characters in books are allowed to grapple with issues that have nothing to do with their racial identity. Often they simply have fun adventures without any heavy personal issues to resolve. Yet all  too often diverse characters, when they appear at all, are merely a tool to teach about a particular problem – or they are the best friend, existing to validate the goodness of the white main character.

too often diverse characters, when they appear at all, are merely a tool to teach about a particular problem – or they are the best friend, existing to validate the goodness of the white main character.

One tip for more inclusive reading is, “Think about the subject matter of your diverse books. Do all your books featuring black characters focus on slavery? Do all your books about Latino characters focus on immigration? Are all your LGBTQ books coming out stories?” Similarly, diverse books are frequently relegated to specific, short-term units, such as Black History Month. But the “observance month can easily lead to the bad habit of featuring these books and culture for one month out of the entire year. Ask yourself: Have we ever taken this approach with books that feature white protagonists?”

Children notice this. Books about people of color risk being labelled Not Fun. Continually choosing books in which people of color are victims communicates that not being white means living a life of misery and suffering. While learning about injustice is crucial, only focusing on oppression reduces the rich complexity of people of color’s lives to a source of pity.

Fortunately there are an increasing number of books out there that show diversity without making it “the problem.” Unfortunately they can be hard to find: the whitewashing of book covers often disguises diverse contents, and these books are frequently not given library subject headers that indicate their diversity since they’re not about race, but something else entirely. Given these difficulties, here are a few Lee & Low titles that deserve a shout out.

Amazing Places, edited by Lee Bennett Hopkins, takes readers on a journey around America to classic landmarks including Niagara Falls, the Mississippi River, the Texas State Fair, and Denali National Park. Poems by authors such as Alma Flor Ada, Linda Sue Park, and Joseph Bruchac are gorgeously complemented by Chris Soentpiet’s and Christy Hale’s illustrations showing racially integrated communities and people of many ethnic backgrounds. Whether the backdrop is a stunning wilderness scene or a cultural attraction, this book celebrates the diverse natural and human beauty of this nation.

Amazing Places, edited by Lee Bennett Hopkins, takes readers on a journey around America to classic landmarks including Niagara Falls, the Mississippi River, the Texas State Fair, and Denali National Park. Poems by authors such as Alma Flor Ada, Linda Sue Park, and Joseph Bruchac are gorgeously complemented by Chris Soentpiet’s and Christy Hale’s illustrations showing racially integrated communities and people of many ethnic backgrounds. Whether the backdrop is a stunning wilderness scene or a cultural attraction, this book celebrates the diverse natural and human beauty of this nation.

Maya’s Blanket/La Manta de Maya by Monica Brown is a bilingual English/Spanish retelling of a classic Yiddish folktale. This charming story of the love between a little girl and her abuelita is firmly rooted in Latino culture, while David Diaz’s lively illustrations show Maya playing with a multiracial group of friends. Scenes of cross-racial friendship such as these have a positive impact on children’s behavior, yet are so rare that in one study the researchers had to create their own materials!

Maya’s Blanket/La Manta de Maya by Monica Brown is a bilingual English/Spanish retelling of a classic Yiddish folktale. This charming story of the love between a little girl and her abuelita is firmly rooted in Latino culture, while David Diaz’s lively illustrations show Maya playing with a multiracial group of friends. Scenes of cross-racial friendship such as these have a positive impact on children’s behavior, yet are so rare that in one study the researchers had to create their own materials!

In Sally Derby’s Sunday Shopping, a grandmother and granddaughter let their imaginations run wild as they use the Sunday paper to inspire flights of fancy. Evie’s mother has been deployed, and her loving presence is a constant backdrop to the daydreams they indulge in as they browse the colorful ads. Shadra Strickland’s vibrant collages bring to life this universal story of strong family bonds. Evie and her Grandma are black. Why? Well, why not? Children from all racial backgrounds can connect to this warm and playful story, and making the characters black when they don’t “need” to be allows their humanity to shine through first and foremost.

In Sally Derby’s Sunday Shopping, a grandmother and granddaughter let their imaginations run wild as they use the Sunday paper to inspire flights of fancy. Evie’s mother has been deployed, and her loving presence is a constant backdrop to the daydreams they indulge in as they browse the colorful ads. Shadra Strickland’s vibrant collages bring to life this universal story of strong family bonds. Evie and her Grandma are black. Why? Well, why not? Children from all racial backgrounds can connect to this warm and playful story, and making the characters black when they don’t “need” to be allows their humanity to shine through first and foremost.

Do you have favorite titles that show diversity through the illustrations without making it an issue in the text? Please share them below!

The daughter of an anthropologist, Laura Reiko Simeon’s passion for diversity-related topics stems from her childhood spent living all over the US and the world. An alumna of the United World Colleges, international high schools dedicated to fostering cross-cultural understanding, Laura has an MA in History from the University of British Columbia, and a Master of Library and Information Science from the University of Washington. She lives near Seattle where she is the Diversity Coordinator and Library Learning Commons Director at Open Window School.

The daughter of an anthropologist, Laura Reiko Simeon’s passion for diversity-related topics stems from her childhood spent living all over the US and the world. An alumna of the United World Colleges, international high schools dedicated to fostering cross-cultural understanding, Laura has an MA in History from the University of British Columbia, and a Master of Library and Information Science from the University of Washington. She lives near Seattle where she is the Diversity Coordinator and Library Learning Commons Director at Open Window School.

Other Guest Posts by Laura Reiko Simeon:

Tearing Down Walls: The Integrated World of Swedish Picture Books

Gender Matters? Swedish Picture Books and Gender Ambiguity

-->

Whether students have a year or more under their belts or are starting school for the first time, a new school year can invoke everything from laughter to tears to giggles and cheers. Teachers face the full spectrum of student feelings about the first day of a new school year: excitement, shyness, doubt, fear, anxiety.

How can we help our students face their feelings and the start of the new school year?

Selecting the right back-to-school read aloud is exciting because of the potential it holds. We can imagine the conversations we will have with our scholars and the connections they will make. We can imagine the safe, welcoming, reading-first space we will inspire.

It may be tempting to concentrate on introducing students to routines and expectations and practicing procedures around sitting on the carpet or signaling for the bathroom. However, building classroom culture is critical to a successful school year. Reading should start on day 1 as part of your strategy for achieving that safe, welcoming, reading-first space.

It may be tempting to concentrate on introducing students to routines and expectations and practicing procedures around sitting on the carpet or signaling for the bathroom. However, building classroom culture is critical to a successful school year. Reading should start on day 1 as part of your strategy for achieving that safe, welcoming, reading-first space.

As you assemble or sort through your read aloud bin for the right mentor texts for the first unit in your scope & sequence, think about which books signal the community and classroom culture you want and your students need.

Pair read alouds that are “elementary school classics” with books that celebrate and recognize your students’ experiences, backgrounds, and interests.

For example, a classic back to school read aloud is Chrysanthemum, by Kevin Henkes, about a young girl’s first day of kindergarten. Henkes captures the feelings of many new students navigating new spaces and friendships.

Now pair that with a text that has characters with identities and experiences that are meaningful to your student population. Yes, first day jitters and excitement are universal, but the additional challenge of being a non-native English speaker or coping with homelessness can tip feelings over from nervous to overwhelmed.

Chrysanthemum, You’re Not Alone!

As part of your preparations for the beginning of the school year, gather a collection of your books related to the first day of school.

Book Pairing Recommendation:

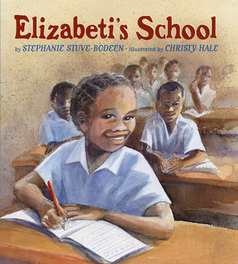

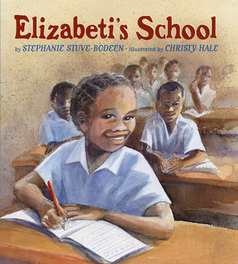

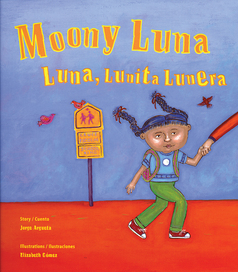

Elizabeti’s School + Moony Luna/ Luna, Lunita Lunera + Chrysanthemum (HarperCollins)

Ideal read-alouds for the start of school should:

- Allow you to introduce and discuss the roles of students and teachers, the classroom, and school in general

- Show young learners that it is normal to have a mixture of feelings during this time of change

- Include a variety of themes and topics: the first day of school, making friends, families and communities, dealing with new situations and separation, helping each other process our emotions/overcome fears, and growing up

Getting students to start talking about how a character grapples with new classmates and the school setting can help them express how they are feeling as well as recognize that others in the room feel exactly the same way. (It also gives you the opportunity to start reading to kids! And show how book-centric your classroom is.)

Activities:

- In the first few days, read more than one character’s first day of school. Ask children to make connections between these stories. Also encourage them to connect their own school experiences to those of characters in the books.

- If students are writing, have children write about something in school that made them feel happy. It may be one or two sentences. For students who are not writing yet, encourage them to dictate their experience for their drawings to an adult who will record their words. Include a space for students to sketch their answer.

- Have students turn to the last page in the book. Then ask them to draw a dream that the character might have that night or imagine what her second day will be like.

- As a whole group, write a class letter as Chrysanthemum to Moony Luna. What advice would she have for Luna about school?

- Finally, create a bin of other back-to-school books (it’s quite a genre!) for students to explore in and outside of class.

Additionally, consider reading your favorite must-read back-to-school book in the students’ first language (or inviting a parent to join alongside you in the reading) if they are English Language Learners. Many of the most popular “classics” are available in other languages as well as authentic literature written as bilingual texts.

Recognizing children’s cultures and their languages is a BIG deal. Too many schools get students’ names wrong from the beginning. More and more schools have English Language Learner populations and multiple languages spoken within one school and classroom. Reading in students’ language or selecting a text that portrays a character your students identify with communicates to them that they matter, their lives matter, and they are going to learn a ton with you this year.

Culturally responsive books with characters and themes about navigating a new school/grade/year:

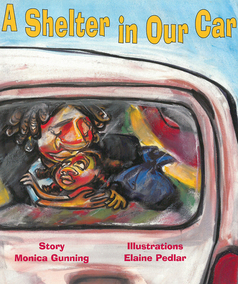

A Shelter in Our Car: Zettie and her Mama left their warm and comfortable home in Jamaica for an uncertain life in the United Sates, and they are forced to live in Mama’s car.

A Shelter in Our Car: Zettie and her Mama left their warm and comfortable home in Jamaica for an uncertain life in the United Sates, and they are forced to live in Mama’s car.

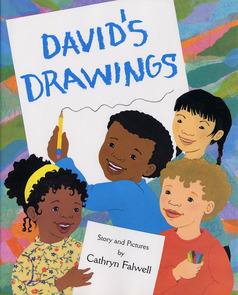

David’s Drawings and Los dibujos de David: Available in Spanish and English, a shy young African American boy makes friends in school by letting his classmates help with his drawing of a bare winter tree. A shy young African American boy makes friends in school by letting his classmates help with his drawing of a bare winter tree.

David’s Drawings and Los dibujos de David: Available in Spanish and English, a shy young African American boy makes friends in school by letting his classmates help with his drawing of a bare winter tree. A shy young African American boy makes friends in school by letting his classmates help with his drawing of a bare winter tree.

Elizabeti’s School and La escuela de Elizabeti: In this contempory Tanzanian story available in English and Spanish, author Stephanie StuveBodeen and artist Christy Hale once again bring the sweet innocence of Elizabeti to life. Readers are sure to recognize this young child’s emotions as she copes with her first day of school and discovers the wonder and joy of learning.

Elizabeti’s School and La escuela de Elizabeti: In this contempory Tanzanian story available in English and Spanish, author Stephanie StuveBodeen and artist Christy Hale once again bring the sweet innocence of Elizabeti to life. Readers are sure to recognize this young child’s emotions as she copes with her first day of school and discovers the wonder and joy of learning.

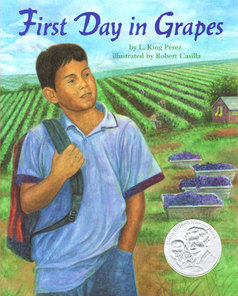

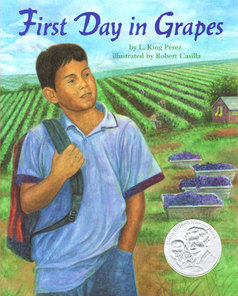

First Day in Grapes and Primer día en las uvas: Available in Spanish and English, the powerful story of a migrant boy who grows in selfconfidence when he uses his math prowess to stand up to the school bullies.

First Day in Grapes and Primer día en las uvas: Available in Spanish and English, the powerful story of a migrant boy who grows in selfconfidence when he uses his math prowess to stand up to the school bullies.

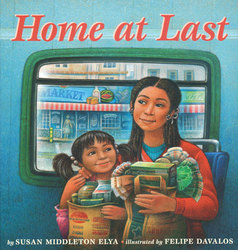

Home at Last and Al fin en casa: A sympathetic tale available in Spanish and English of a motherdaughter bond and overcoming adversity, brought to life by the vivid illustrations of Felipe Davalos.

Home at Last and Al fin en casa: A sympathetic tale available in Spanish and English of a motherdaughter bond and overcoming adversity, brought to life by the vivid illustrations of Felipe Davalos.

Moony Luna/ Luna, Lunita Lunera: Bilingual English/Spanish. A bilingual tale about a young girl afraid to go to school for the first time.

Moony Luna/ Luna, Lunita Lunera: Bilingual English/Spanish. A bilingual tale about a young girl afraid to go to school for the first time.

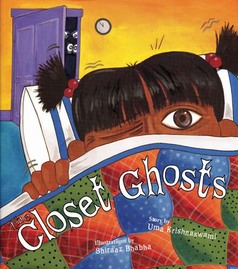

The Closet Ghosts: Moving to a new place is hard enough without finding a bunch of mean, nasty ghosts in your closet. When Hanuman, the Hindu monkey god, answers Anu’s plea for help, Anu rejoicesuntil she realizes that those pesky ghosts don’t seem to be going anywhere.

The Closet Ghosts: Moving to a new place is hard enough without finding a bunch of mean, nasty ghosts in your closet. When Hanuman, the Hindu monkey god, answers Anu’s plea for help, Anu rejoicesuntil she realizes that those pesky ghosts don’t seem to be going anywhere.

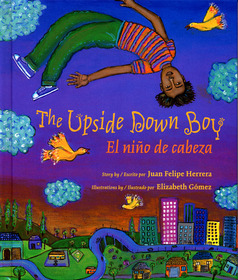

The Upside Down Boy/ El niño de cabeza: Bilingual English/Spanish. Awardwinning poet Juan Felipe Herrera’s engaging memoir of the year his migrant family settled down so that he could go to school for the first time.

The Upside Down Boy/ El niño de cabeza: Bilingual English/Spanish. Awardwinning poet Juan Felipe Herrera’s engaging memoir of the year his migrant family settled down so that he could go to school for the first time.

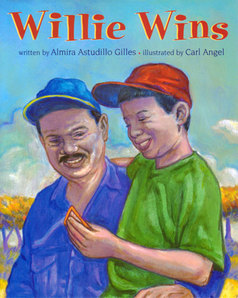

Willie Wins: In this heart-warming story, a boy gets beyond peer pressure and comes to appreciate the depth of his father’s love.

Willie Wins: In this heart-warming story, a boy gets beyond peer pressure and comes to appreciate the depth of his father’s love.

For further reading on starting the school year:

Marilisa Jimenez-Garcia, research associate at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College, CUNY, graduated from the University of Florida with a PhD in English, specializing in American literature/studies, nationalism, and children’s and young adult literature. Marilisa is also a National Council for Teachers of English (NCTE) Cultivating New Voices Among Scholar of Color Fellow. She is currently working on a manuscript on U.S. Empire, Puerto Rico, and American children’s culture. She is the recipient of the Puerto Rican Studies Association Dissertation Award 2012 and the University of Florida’s Dolores Auzenne Dissertation Award. Her scholarly work appears in publications such as Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education and CENTRO Journal. She has also published reviews in International Research in Children’s Literature and Latino Studies.

Marilisa Jimenez-Garcia, research associate at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College, CUNY, graduated from the University of Florida with a PhD in English, specializing in American literature/studies, nationalism, and children’s and young adult literature. Marilisa is also a National Council for Teachers of English (NCTE) Cultivating New Voices Among Scholar of Color Fellow. She is currently working on a manuscript on U.S. Empire, Puerto Rico, and American children’s culture. She is the recipient of the Puerto Rican Studies Association Dissertation Award 2012 and the University of Florida’s Dolores Auzenne Dissertation Award. Her scholarly work appears in publications such as Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education and CENTRO Journal. She has also published reviews in International Research in Children’s Literature and Latino Studies.

How might the legacy of the first Latina librarian at the New York Public Library speak to recent ‘human events’? 2014 was a landmark year with regard to discussions of race, diversity, and young people of color in American society. A game-changing year in which much of the rhetoric of multiculturalism we often use when preparing our young citizens unraveled. Indeed, by summer 2014, events had sparked a campaign by educators looking for new approaches and resources on how to discuss race in the classroom (Marcia Chatelain, “Ferguson Syllabus”). Those of us focused on the narrative and social literacy of young people seem at a place of no return—a place where we must admit that equality is not so in the Promised Land.(1)

As an American literature and childhood studies researcher, I was not surprised that 2014’s list of recurring headlines, including court rulings, protests, and policing, also contained debates about children’s books. What young people read, and the worlds, norms, histories, and people therein, have always mattered in the U.S. Children’s reading materials (e.g. fiction, history, and textbooks) have always been at the forefront of the “culture wars,” particularly after the Cold War. Ethical pleas for kid lit diversity are also nothing new. The start of Pura Belpré’s NYPL career in the 1920s is actually marked by a question similar to Walter Dean Myer’s op-ed in New York Times: “Where are the people of color in children’s books?” In Belpré’s case, she wanted to represent what she saw as the history and heritage of the Puerto Rican child. She began writing her own books as result of finding Puerto Rican culture absent from the shelves. However, considering the contributions by people of color to children’s literature over the last 90 years or so including Belpré, and numerous studies on the lack of representation, we find that calls for kid lit diversity consistently fail. (For further information see Nancy Larrick’s study “The All White World of Children’s Literature” The Saturday Review, September 11, 1965 and also work by the Council for Interracial Children’s Books). Post-2014, what is remarkable about our current moment is the amount of mainstream and field-wide attention the diversity issue has garnered. It also remains to be seen how the incorporation of We Need Diverse Books will impact the literary world.

Here, I want to offer some reflections on Belpré’s career and legacy which might enable us to have a more critical, productive conversation on diversity:

Here, I want to offer some reflections on Belpré’s career and legacy which might enable us to have a more critical, productive conversation on diversity:

Conversation instead of compartmentalization. People of color including librarians and storytellers such as Pura Belpré and Augusta Baker were active (1920s and 1930s) when American children’s literature was advancing as a field with its own set of publishers, librarians, and prizes. The African American and Puerto Rican community have a longstanding tradition of employing children’s literature as a vehicle for imagination, cultural pride, and social consciousness.(2) Yet, systemically, people of color are left out of the conversation when it comes to accessing the breadth of children’s literature as an American tradition. Diversity should be understood as a conversation, rather than as a system of containing U.S. populations as compartments (with respective histories, literature, and cultural iconography) that never converge. A compartmentalized view hinders our ability to envision people of color as participants in the imagined landscapes of American history and culture—past, present, and future. Even our prizing system, including the Belpré Medal, tends to follow this logic of best Latino children’s literature, best African American children’s literature, but when it comes to best American children’s literature, people of color have historically fared in the single digits. Prizes such as the Belpré foster cultural pride, solidarity, and a market for Latino authors, yet they also continue the logic of compartmentalization.

Relevant instead of relatable. Belpré’s stories were based on folklore which some Latino/a children might find familiar. But, Belpré’s books are also artistic fiction. In other words, they are just stories to be enjoyed by whoever might enjoy them. As a teacher, I had to check my use of the term “relatable” when discussing literature with young people. Once we were reading The Outsiders (1967) and Nicholasa Mohr’s Nilda (1973) as means of comparing how young people grow up and encounter violence. I always remember one student closing her copy of Nilda, saying, “This is about culture, not about teens. I couldn’t really relate.” I was puzzled seeing that key characters in both books were adolescents. Certainly, when a Latino/a author writes about Latino/a characters, the story is shaped by Latino/a culture—which also varies in terms of racial, regional, gender, and national identity. But, the same is true for any author. Oliver Twist is a mainstream story, but it is also a commentary on 19th century childhood—a celebrated time for some who could afford it—and the conditions for poor, orphaned youth. Stories are always about culture. Yet, what we catalogue as “foreign” or “other” tells us more about ourselves than about the stories we read.

Imperfect characters instead of superheroes. When it comes to young readers, we have a tendency to want to simplify things that we adults even have a hard time understanding. Clearly, cognition is an issue. But our desire to create clear-cut heroes and villains in American history, or any history for that matter, will fail at best. Parents and teachers often battle for the representation of marginalized groups in textbooks. But, they rarely argue over whether or not America is an exceptional nation (Zimmerman).(3) Our approach to teaching and systemizing a heritage of American children’s literature should emphasize that this is a great nation shaped by imperfect people, whether dominant or marginalized. It’s complicated. Those we might see as heroes don’t always win or dominate “the bad guys.” In Belpré’s folklore, she often underlined this sense of imperfection. For example, she showed that even though the Tainos had beautiful values and bravery, they didn’t win every battle against the Spaniards (Once in Puerto Rico, 1977). Even the Medal named in her honor symbolizes this sense of complicated, converging histories in its use of the term “Latino/a.” This one term—which some even within our communities cannot agree upon—stands for those who represent multiple nations, histories, languages, and races. It’s not a perfect term. Nor, as my father always tells me, is this a perfect world. Sooner or later, our young people are going to learn that apart from any storybook or textbook. The pressure to present a perfect America often means that we erase the voices of the marginalized.

Here are some practical ways these principles might play out in the classroom:

- Consider talking with students about diversity and how they “see themselves” in books: Even with the best intentions, we have a tendency to talk about young people without asking their opinions. Try to have the start with them. If they are a bit older, have them read Walter Dean Myers op-ed for class discussion. You might ask them to journal about issues such as cultural authenticity in a book read for the class. Or you might ask them to write a story, graphic novel, science fiction adventure, or picture book about their communities as an assignment.

- Consider classroom presentation of books: We need to stop relegating people of color to special months in which we celebrate and include their stories. Although focusing on a particular group has its benefits, this should not override the other 11-months when they are excluded or barely mentioned. This also includes displays of books in your class library. Do you organize books alphabetically by author or by nationality and country?

- Consider genre: Avoid relying only on folklore, historical fiction, and biographies. This is also something publishers need to consider. Latino/as in particular have one of the lowest percentages in fantasy, science, and science fiction. Look for books in which people of color play active roles in actual and imagined societies.

For further reading:

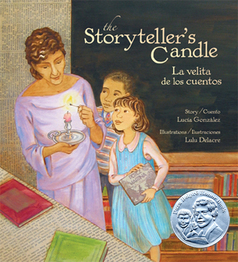

Pura Belpré Lights the Storyteller’s Candle: Reframing the Legacy of a Legend and What it Means for the Fields of Latino/a Studies and Children’s Literature by Marilisa Jiménez-García in CENTRO Journal.

- R.L. L’Heureux, Inequality in the Promised Land (Stanford University Press, 2014)

- Katherine Capshaw-Smith, Children’s Literature of the Harlem Renaissance (Indiana University Press, 2006) and Marilisa Jimenez-Garcia, “Pura Belpré Lights the Storyteller’s Candle” (CENTRO Journal, Vol. 26, No. 1)

- Jonathan Zimmerman, Whose America?: Culture Wars in the Public Schools (Harvard University Press, 2002)

By:

Jen Robinson,

on 2/19/2014

Blog:

Jen Robinson

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literacy,

teaching,

Parents,

book selection,

raising readers,

Baby Bookworm,

nerdy book club,

growing bookworms,

bookshaming,

priscilla thomas,

Add a tag

A post at the Nerdy Book Club this week really made me think. Priscilla Thomas, an 11th grade teacher, wrote about the repercussions of what she called "bookshaming". Thomas says:

"To be clear, opinion and disagreement are important elements of literary discourse. Bookshaming, however, is the dismissive response to another’s opinion. Although it is sometimes justified as expressing an opinion that differs from the norm, or challenging a popular interpretation, bookshaming occurs when “opinions” take the form of demeaning comments meant to shut down discourse and declare opposing viewpoints invalid."

She goes on to enumerate five ways that bookshaming (particularly by teachers) can thwart the process of nurturing "lifelong readers." I wish that all teachers could read this post.

But of course I personally read this as a parent. Thomas forced me to consider an incident that had taken place in my household a couple of weeks ago. We were rushing around to get out of the house to go somewhere, but my daughter asked me to read her a book first. The book she wanted was Barbie: My Fabulous Friends! (which she had picked out from the Scholastic Book Fair last fall).

But of course I personally read this as a parent. Thomas forced me to consider an incident that had taken place in my household a couple of weeks ago. We were rushing around to get out of the house to go somewhere, but my daughter asked me to read her a book first. The book she wanted was Barbie: My Fabulous Friends! (which she had picked out from the Scholastic Book Fair last fall).

I did read this book about Barbie and her beautiful, multicultural friends. But at the end I made some remark about it being a terrible book. And even as I said it, I KNEW that it was the wrong thing to say. Certainly, it is not to my taste. It's just little profiles of Barbie's friends - no story to speak of. But my daughter had picked out this book from the Book Fair, and she had liked it enough to ask me to read it to her. She seemed to be enjoying it. And I squashed all of that by criticizing her taste.

Two weeks later, I am still annoyed with myself. Priscilla Thomas' article helped me to better understand why. She said: "When we make reading about satisfying others instead of our own enjoyment and education, we replace the joy of reading with anxiety." What I WANT is for my daughter to love books. And if I have to grit my teeth occasionally over a book that irritates me, so what?

Rather than continue to beat myself up over this, I have resolved to be better. The other night I read without a murmur The Berenstain Bears Come Clean for School by Jan and Mike Berenstain, which is basically a lesson on how and why to avoid spreading germs at school. As I discussed here, that same book has helped my daughter to hone her skills in recommending books. It is not a book I would have ever selected on my own. But I'm going to hold on to the image of my daughter flipping to the last page of the book, face shining, to tell me how funny the ending was.

Rather than continue to beat myself up over this, I have resolved to be better. The other night I read without a murmur The Berenstain Bears Come Clean for School by Jan and Mike Berenstain, which is basically a lesson on how and why to avoid spreading germs at school. As I discussed here, that same book has helped my daughter to hone her skills in recommending books. It is not a book I would have ever selected on my own. But I'm going to hold on to the image of my daughter flipping to the last page of the book, face shining, to tell me how funny the ending was.

Growing bookworms is about teaching our children to love reading (see a nice post by Carrie Gelson about this at Kirby Larson's blog). They're not going to love reading if we criticize their tastes, and make them feel anxious or defensive. I'm sorry that I did that to my daughter over the Barbie book, and I intend to do my best not to do that again. If this means reading 100 more Barbie books over the next couple of years, so be it. Of course I can and will introduce her to other authors that are more to my own taste, to see which ones she likes. But I will respect her taste, too.

© 2014 by Jennifer Robinson of Jen Robinson's Book Page. All rights reserved. You can also follow me @JensBookPage or at my Growing Bookworms page on Facebook. This site is an Amazon affiliate.

Noodle sent me this infographic on finding your next children's book. The titles were suggested by the Kidlitosphere's own Betsy Bird, the New York Public Library's Youth Materials Collections Specialist.

See any titles you like?

Those of you reading this blog are professionals at reading aloud, whether to your own kids or the kids in your classroom or that come into your library or bookstore.If you know of parents or individuals that might not be sure how to go about selecting books for their young readers, or how to incorporate story time into their daily routine, here are a couple of articles that you might want to pass along to them:A How-To on Reading Aloud to Your Kids

Harder Books Aren't Always Better Books: Talking with Parents about Text Difficulty

Choice Literacy, the source for this second article, is a great website which includes many great articles for educators and literacy professionals. They offer many great tips for free, or you can sign up for an annual membership ($99 per year) to receive:- All site materials in an ad-free environment, including hundreds of articles, web-based videos, and workshop e-Guides

- Continuously updated content

- Downloadable tips, tools, and templates for literacy leaders, curriculum specialists, principals, and teachers

- The latest writing from your favorite teacher authors before it appears in their next book

- Dozens of videos filmed and edited by our award-winning crew of videographers and technicians

- Discounts on products and services available only to members

If you know of more resource sites to share, please add them in the comment section.

![]() ibrarian and Diversity Coordinator Laura Reiko Simeon. Welcome, Laura!

ibrarian and Diversity Coordinator Laura Reiko Simeon. Welcome, Laura! too often diverse characters, when they appear at all, are merely a tool to teach about a particular problem – or they are the best friend, existing to validate the goodness of the white main character.

too often diverse characters, when they appear at all, are merely a tool to teach about a particular problem – or they are the best friend, existing to validate the goodness of the white main character. Amazing Places, edited by Lee Bennett Hopkins, takes readers on a journey around America to classic landmarks including Niagara Falls, the Mississippi River, the Texas State Fair, and Denali National Park. Poems by authors such as Alma Flor Ada, Linda Sue Park, and Joseph Bruchac are gorgeously complemented by Chris Soentpiet’s and Christy Hale’s illustrations showing racially integrated communities and people of many ethnic backgrounds. Whether the backdrop is a stunning wilderness scene or a cultural attraction, this book celebrates the diverse natural and human beauty of this nation.

Amazing Places, edited by Lee Bennett Hopkins, takes readers on a journey around America to classic landmarks including Niagara Falls, the Mississippi River, the Texas State Fair, and Denali National Park. Poems by authors such as Alma Flor Ada, Linda Sue Park, and Joseph Bruchac are gorgeously complemented by Chris Soentpiet’s and Christy Hale’s illustrations showing racially integrated communities and people of many ethnic backgrounds. Whether the backdrop is a stunning wilderness scene or a cultural attraction, this book celebrates the diverse natural and human beauty of this nation. Maya’s Blanket/La Manta de Maya by Monica Brown is a bilingual English/Spanish retelling of a classic Yiddish folktale. This charming story of the love between a little girl and her abuelita is firmly rooted in Latino culture, while David Diaz’s lively illustrations show Maya playing with a multiracial group of friends. Scenes of cross-racial friendship such as these have a positive impact on children’s behavior, yet are so rare that in one study the researchers had to create their own materials!

Maya’s Blanket/La Manta de Maya by Monica Brown is a bilingual English/Spanish retelling of a classic Yiddish folktale. This charming story of the love between a little girl and her abuelita is firmly rooted in Latino culture, while David Diaz’s lively illustrations show Maya playing with a multiracial group of friends. Scenes of cross-racial friendship such as these have a positive impact on children’s behavior, yet are so rare that in one study the researchers had to create their own materials! In Sally Derby’s Sunday Shopping, a grandmother and granddaughter let their imaginations run wild as they use the Sunday paper to inspire flights of fancy. Evie’s mother has been deployed, and her loving presence is a constant backdrop to the daydreams they indulge in as they browse the colorful ads. Shadra Strickland’s vibrant collages bring to life this universal story of strong family bonds. Evie and her Grandma are black. Why? Well, why not? Children from all racial backgrounds can connect to this warm and playful story, and making the characters black when they don’t “need” to be allows their humanity to shine through first and foremost.

In Sally Derby’s Sunday Shopping, a grandmother and granddaughter let their imaginations run wild as they use the Sunday paper to inspire flights of fancy. Evie’s mother has been deployed, and her loving presence is a constant backdrop to the daydreams they indulge in as they browse the colorful ads. Shadra Strickland’s vibrant collages bring to life this universal story of strong family bonds. Evie and her Grandma are black. Why? Well, why not? Children from all racial backgrounds can connect to this warm and playful story, and making the characters black when they don’t “need” to be allows their humanity to shine through first and foremost. The daughter of an anthropologist, Laura Reiko Simeon’s passion for diversity-related topics stems from her childhood spent living all over the US and the world. An alumna of the United World Colleges, international high schools dedicated to fostering cross-cultural understanding, Laura has an MA in History from the University of British Columbia, and a Master of Library and Information Science from the University of Washington. She lives near Seattle where she is the Diversity Coordinator and Library Learning Commons Director at Open Window School.

The daughter of an anthropologist, Laura Reiko Simeon’s passion for diversity-related topics stems from her childhood spent living all over the US and the world. An alumna of the United World Colleges, international high schools dedicated to fostering cross-cultural understanding, Laura has an MA in History from the University of British Columbia, and a Master of Library and Information Science from the University of Washington. She lives near Seattle where she is the Diversity Coordinator and Library Learning Commons Director at Open Window School.

“Who do you think I am?”, is about the potential and possibilities in ALL children. It is positive and uplifting with diverse characters. It was illustrated by a teenager, who receives royalties for each copy sold. The publisher, Positively Publishing Kids is dedicated to creating positive, upbeat diverse books, while working with kids ages 14-18 to illustrate their titles.

Thank you! This is what I have been trying to say for the longest time. We need books about slavery, internment camps, etc., sure. But we also need books about regular kids who just happen to not be white. They don’t need to always talk about race. They just need to be fun books with diverse characters. I hope we can look forward to more of these!

Another Lee & Low title: JUNA’S JAR written by Jane Bahk and illustrated by Felicia Hoshino

_”More, More, More” Said the Baby_ by Vera B. Williams, _Grandma Lena’s Big Ol’ Turnip_ by Denia Lewis Hester, practically everything by Ezra Jack Keats, and _The Bakeshop Ghost_ by Jacqueline Oqburn are favorites of mine (and my kids!) that meet these criteria. Great article.

Well said.

This is a topic near and dear to my heart! I am passionate about finding these types of books and making them accessible. Over on the Everyday Diversity blog, I recently published a list of over a hundred titles that show representational diversity, and the plan is to continue adding to the list as well as providing reviews and suggestions for library and classroom use. A few of these Lee & Low titles are new to me, so I’ll be sure to add them!

Thank you

Anna Haase Krueger

http://everydaydiversity.blogspot.com/