By Dennis Baron

There’s a federal law that defines writing. Because the meaning of the words in our laws isn’t always clear, the very first of our federal laws, the Dictionary Act–the name for Title 1, Chapter 1, Section 1, of the U.S. Code–defines what some of the words in the rest of the Code mean, both to guide legal interpretation and to eliminate the need to explain those words each time they appear. Writing is one of the words it defines, but the definition needs an upgrade.

The Dictionary Act consists of a single sentence, an introduction and ten short clauses defining a minute subset of our legal vocabulary, words like person, officer, signature, oath, and last but not least, writing. This is necessary because sometimes a word’s legal meaning differs from its ordinary meaning. But changes in writing technology have rendered the Act’s definition of writing seriously out of date.

The Dictionary Act tells us that in the law, singular includes plural and plural, singular, unless context says otherwise; the present tense includes the future; and the masculine includes the feminine (but not the other way around–so much for equal protection).

The Act specifies that signature includes “a mark when the person making the same intended it as such,” and that oath includes affirmation. Apparently there’s a lot of insanity in the law, because the Dictionary Act finds it necessary to specify that “the words ‘insane’ and ‘insane person’ and ‘lunatic’ shall include every idiot, lunatic, insane person, and person non compos mentis.”

The Dictionary Act also tells us that “persons are corporations . . . as well as individuals,” which is why AT&T is currently trying to convince the Supreme Court that it is a person entitled to “personal privacy.” (The Act doesn’t specify whether “insane person” includes “insane corporation.”)

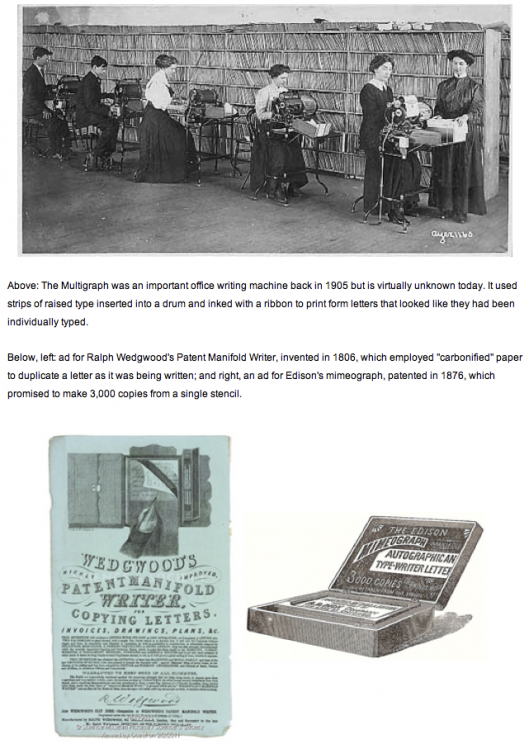

And then there’s the definition of writing. The final provision of the Act defines writing to include “printing and typewriting and reproductions of visual symbols by photographing, multigraphing, mimeographing, manifolding, or otherwise.” There’s no mention of Braille, for example, or of photocopying, or of computers and mobile phones, which seem now to be the primary means of transmitting text, though presumably they and Facebook and Twitter and all the writing technologies that have yet to appear are covered by the law’s blanket phrase “or otherwise.”

Federal law can’t be expected to keep up with every writing technology that comes along, but the newest of the six kinds of writing that the Dictionary Act does refer to–the multigraph–was invented around 1900 and has long since disappeared. No one has ever heard of multigraphing, or of manifolding, an even older and deader technology, and for most of us the mimeograph is at best a dim memory.

Congress considers writing important enough to the nation’s well-being to include it in the Dictionary Act, but not important enough to bring up to date, and now, with the 2012 election looming, no member of Congress is likely to support a revision to the current definition that is semantically accurate yet co