new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: italian literature, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 8 of 8

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: italian literature in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Catherine,

on 10/3/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

william shakespeare,

Infographics,

printing press,

italian literature,

english literature,

infographic,

*Featured,

Theatre & Dance,

literacy rates,

Arts & Humanities,

Illuminating Shakespeare,

Shakespeare's Influences,

Renaissance literacy,

Renaissance literature,

Literature,

shakespeare,

Add a tag

George Bernard Shaw once remarked on William Shakespeare's "gift of telling a story (provided some one else told it to him first)." Shakespeare knew the works of many great writers, such as Raphael Holinshed, Ludovico Ariosto, and Geoffrey Chaucer. How did these men, and many others, influence Shakespeare and his work?

The post Who was on Shakespeare’s bookshelf? [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 2/27/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

medieval literature,

Dante: A Very Short Introduction,

David Robey,

Paradiso,

peter hainsworth,

The Divine Comedy,

Literature,

Religion,

shakespeare,

Philosophy,

VSI,

Europe,

very short Introductions,

theology,

Inferno,

Dante,

italian literature,

Add a tag

Dante can seem overwhelming. T.S. Eliot’s peremptory declaration that ‘Dante and Shakespeare divide the modern world between them: there is no third’ is more likely to be off-putting these days than inspiring. Shakespeare’s plays are constantly being staged and filmed, and in all sorts of ways, with big names in the big parts, and when we see them we can connect with the characters and the issues with not too much effort.

The post Why we should read Dante as well as Shakespeare appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 4/25/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

OWC,

Oxford World's Classics,

Latin,

galileo,

Humanities,

italian literature,

*Featured,

Classics & Archaeology,

tasso,

classical studies,

court poetry,

Mark Davie,

the liberation of jerusalem,

torquato tasso,

tasso’s,

Poetry,

Literature,

classics,

Add a tag

By Mark Davie

Torquato Tasso, who died in Rome on 25 April 1595, desperately wanted to write a classic. The son of a successful court poet who had been brought up on the Latin classics, he had a lifelong ambition to write the epic poem which would do for counter-reformation Italy what Virgil’s Aeneid had done for imperial Rome. From his teenage years on, he worked on drafts of a poem on the first crusade which had ‘liberated’ Jerusalem from its Muslim rulers in 1099, a subject which he deemed appropriate for a Christian epic. His ambition reflected the climate in which he grew up: his formative years (he was born in 1544) saw a newly assertive orthodoxy both in literary theory (dominated by Aristotle’s Poetics, published in a Latin translation in 1536) and in religion (the Council of Trent, convened to meet the challenge of Luther’s revolt, was in session intermittently between 1545 and 1563). Those who saw Aristotle’s text as normative insisted that an epic must deal with a single historical theme in a uniformly elevated style, while the decrees emanating from Trent re-asserted the authority of the church and took an increasingly hard line against heresy. As he worked on his poem, Tasso was nervously anxious not to offend either of these constituencies.

The trouble was that his most immediate model – one whose influence he could not have ignored even if he had wanted to – was very far from conforming to the new orthodoxies. Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, a multilayered narrative loosely (very loosely) located in the historical setting of Charlemagne’s wars against the Moors in Spain, was published in 1532, and was written in more easy-going times. Ariosto could criticize the Italian rulers of his day, including the papacy, and introduce episodes into his poem which provocatively questioned conventional values, whether rational, social, or sexual, without worrying about the consequences. He could be equally casual about literary proprieties: his freewheeling poem indulged in constant romantic deviations from its main plot, such as it was, and its tone was teasingly elusive, always maintaining an ironic distance between the narrator and his subject-matter.

The trouble was that his most immediate model – one whose influence he could not have ignored even if he had wanted to – was very far from conforming to the new orthodoxies. Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, a multilayered narrative loosely (very loosely) located in the historical setting of Charlemagne’s wars against the Moors in Spain, was published in 1532, and was written in more easy-going times. Ariosto could criticize the Italian rulers of his day, including the papacy, and introduce episodes into his poem which provocatively questioned conventional values, whether rational, social, or sexual, without worrying about the consequences. He could be equally casual about literary proprieties: his freewheeling poem indulged in constant romantic deviations from its main plot, such as it was, and its tone was teasingly elusive, always maintaining an ironic distance between the narrator and his subject-matter.

The Orlando furioso was hardly a model for the poem Tasso set out to write; and yet it was hugely popular, and Tasso clearly read and admired it as much as anyone. So Tasso’s poem, as he reluctantly agreed to publish it in 1581 after 20 years of writing and rewriting, embodies the tension between his declared aim and the poem his instincts impelled him to write. It would be hard to argue that the Gerusalemme liberata (The Liberation of Jerusalem) is an unqualified success as a celebration of counter-reformation Christianity; instead it is something much more interesting, an expression of the inner contradictions of late sixteenth-century culture as they were felt by a sensitive – sometimes hyper-sensitive – and gifted poet.

Some of Tasso’s drafts had leaked out during the poem’s long gestation and had been published without his consent, so the poem was eagerly awaited, and it immediately had its devotees. Not everyone, however, was impressed. Among those who were not was Galileo, who wrote a series of acerbic notes on the poem some time before 1609. His criticisms are mostly on details of language and style, but in one revealing comment he compares Tasso’s poetic conceits to ostentatiously difficult dance steps, which are pleasing only if they are ‘carried through with supreme accomplishment, so that their gracefulness overrides their affectation’. Grazia versus affettazione: the terms are taken from Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier, that indispensable guide to Renaissance manners which decreed that the courtier’s accomplishments should be displayed with an appearance of effortless nonchalance. Tasso’s offence against courtly manners was that he tried too hard.

The Gerusalemme liberata is indeed full of unresolved tensions – between historical chronicle and romantic fantasy, sensuality and solemnity, the broad sweep of history and the playing out of individual passions. They are what bring the poem to life today, long after the crusades have lost their appeal as a topic for celebration. Galileo rebukes one of Tasso’s heroes for being too easily deflected from his duty by love: ‘Tancredi, you coward, a fine hero you are! You were the first to be chosen to answer Argante’s challenge, and then when you come face to face with him, instead of confronting him you stop to gaze on your lady love’. Tancredi does admittedly cut a rather ludicrous figure when he is transfixed by catching sight of Clorinda just as he is about to accept the Saracen champion’s challenge, but what Galileo didn’t realise was that the very vehemence of his indignation was a testimony to the effectiveness of Tasso’s writing. Plenty of poets wrote about how love mocks the pretentions of would-be heroes, but few dramatised it so effectively – and only Tasso could have written the scene, memorably set to music by Monteverdi, where Tancredi meets Clorinda in single combat, her identity (and her gender) concealed under a suit of armour, and recognises her only when he has mortally wounded her and he baptises her before she dies in his arms.

Galileo was wrong about Tasso’s poem. The very qualities which he deplored make it a classic which inspired poets from Spenser and Milton to Goethe and Byron, composers from Monteverdi to Rossini, and painters from Poussin to Delacroix, and which is still a compelling read today.

Mark Davie taught Italian at the Universities of Liverpool and Exeter. His interests focus particularly on the relation between learned and popular culture, and between Latin and the vernacular, in Italy in the Renaissance. In Oxford World’s Classics he has written the introduction and notes to Max Wickert’s translation of The Liberation of Jerusalem, and has translated (with William R. Shea) the Selected Writings of Galileo.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Statue of Torquato Tasso by Luigi Chiesa. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post How to write a classic appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 9/7/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

professor,

Dante,

philosopher,

galileo,

Humanities,

italian literature,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

Science & Medicine,

galileo’s,

Ariosto,

Commedia dell’Arte,

courtier,

Dialogue on the two chief world systems,

Gerusalemme Liberata,

John L. Heilbron,

Orlando Furioso,

Petrarch,

Tasso,

littérateur,

Literature,

Add a tag

By John L. Heilbron

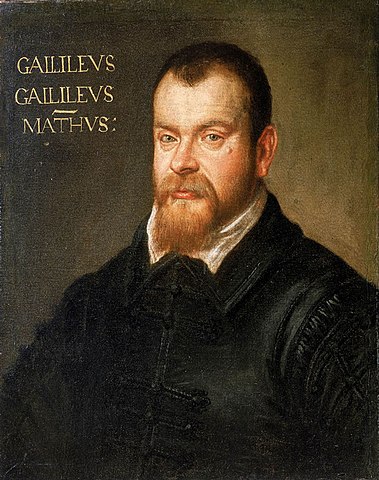

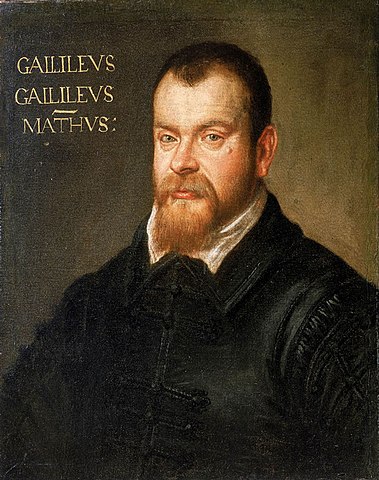

Galileo Galilei by Domenico Tintoretto, 1605-1607.

Galileo is not a fresh subject for a biography. Why then another? The character of the man, his discovery of new worlds, his fight with the Roman Catholic Church, and his scientific legacy have inspired many good books, thousands of articles, plays, pictures, exhibits, statues, a colossal tomb, and an entire museum. In all this, however, there was a chink.

Galileo cultivated an interest in Italian literature. He commented on the poetry of Petrarch and Dante and imitated the burlesques of Berni and Ruzzante. His special favorite was Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, which he prized for its balance of form, wit, and nonsense. His special dislike was Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata (The Liberation of Jerusalem), which violated his notions of heroic behavior and ordinary prosody. Galileo tried his hand at sonnets, sketched plots in the style of the Commedia dell’Arte, and delivered much of his science in dialogues.

The literary side of Galileo is not a discovery; a large specialist literature is devoted to it. But there is a gap in scholarship between the literary Galileo and the rest of him. How were his choices in science and literature complementary and reinforcing? What might be learned from his pronounced literary preferences about the unusual and creative features of his physics? How does Galileo’s praise of Ariosto and criticism of Tasso, on the one hand, parallel his embrace of Archimedes and rejection of Aristotle on the other?

Usually Galileo enters his biography already possessed of most of the convictions and concerns that prompted his discoveries and precipitated his troubles. One reason for endowing him with such precocity is that the documentation for his life before the age of 35 is relatively sparse. In contrast, a quantity of reliable information exists for his later life, after he had transformed a popular toy into an astronomical telescope and himself from a Venetian professor into a Florentine courtier (that happened in 1609/10 when he was 45). By paying attention to his early literary pursuits and associates, however, it is possible to tease out enough about his circumstances as a young man to give him a character different from the cantankerous star-gazer, abstract reasoner, and scientific martyr he became.

A quarrelsome philosopher, half-professor and half-courtier, whose discoveries refashioned the heavens and whose provocative use of them brought him into hopeless conflict with authority, is an attractive subject for portraiture. Add Galileo’s life-long engagement with imaginative writing and the would-be portraitist has his or her hands full. But the resultant picture, even if well-executed, would be a caricature. Galileo initially made his living and gained his reputation as a mathematician. Leave out his mathematics and you may have a compelling character, but not Galileo.

The mathematician and the littérateur have different ways of arguing. To fit together, one sometimes must give way. Galileo’s great polemical work, Dialogue on the two chief world systems, which misleadingly resembles a work of science, frequently privileges rhetoric over mathematics. When the scientific arguments are weakest, the two protagonists in the Dialogue who represent Galileo (his dead buddies Salviati and Sagredo) outdo one another in praising his contrivances and in twitting the third party to the discussions, the bumbling good-natured school philosopher Simplicio, for ignorance of geometry.

The mathematical inventions of the Dialogue that Galileo’s creatures noisily rate as unsurpassed marvels are precisely those that have given commentators the greatest difficulty. These inventions are extremely clever but evidently flawed if taken to be true of the world in which we live. Commentators tend either to interpret the cleverness as shrewd anticipations of later science or to condemn the shortfalls as just plain errors. From my point of view, these marvels should be interpreted as literary devices, conundrums, extravaganzas, inventions too good not to be true in some world if not in ours. They are hints at the form, not the completed ingredients, of a mathematical physics. Galileo’s old Dialogue and today’s Physical Review belong to different genres. Unfortunately, just as the Dialogue was not intended to meet the requirements of accuracy and verisimilitude of modern science journals, so the journals don’t reward the sort of wit and style with which Galileo brought together his literary aspirations, polemical agenda, and scientific insights.

John Heilbron is Professor of History and Vice Chancellor Emeritus of the University of California at Berkeley. One of the most distinguished historians of science, his books include Galileo, The Sun in the Church (a New York Times Notable Book) and The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

The latest addition to our Reviews Section is joint review by Sarah 2 and Quantum Sarah on Alessandro Baricco’s Emmaus, which is translated from the Italian by Mitch Ginsburg and is available from McSweeney’s.

Here is an excerpt from their review:

Alessandro Baricco’s latest novel, Emmaus, centers on the friendship of four working-class Catholic adolescents and their shared love for a tragic, sexual young woman named Andre. The plot of the novel follows the trajectory of a classic loss of innocence story, but Baricco immediately complicates this definition. What distinguishes Emmaus from other narratives of this archetype is its ambiguous stance in respect to Catholicism and sin. It would be a grievous oversimplification to say that the boys live in a world of repression and then find truth, or that they are innocent, pure souls in childhood and are subsequently corrupted in adolescence. To the contrary, Baricco distinctly avoids this simplistic dichotomy of good and evil: the narrator and his friends possess constant awareness of promiscuity and violence, but they don’t label it as such.

Click here to read their entire review.

As with years past, we’re going to spend the next three weeks highlighting the rest of the 25 titles on the BTBA fiction longlist. We’ll have a variety of guests writing these posts, all of which are centered around the question of “Why This Book Should Win.” Hopefully these are funny, accidental, entertaining, and informative posts that prompt you to read at least a few of these excellent works.

Click here for all past and future posts in this series.

New Finnish Grammar by Diego Marani, translated by Judith Landry

Language: Italian

Country: Italy

Publisher: Dedalus

Why This Book Should Win: Because Marani invented Europanto, a “mock international auxiliary language.”

Today’s post is written by the amazing Daniel Hahn, who is both a writer and translator AND a program director at the British Centre for Literary Translation. Once upon a time, we spent a week together at a palace in Salzburg, Austria.

It’s September 1943. A man is found close to death on the quayside at Trieste. He’s wearing a sailor’s jacket, tagged with the name Sampo Karjalainen. He is brought on-board a German hospital ship, the Tubingen, and revived by a kindly doctor. Dr Friari is a Finn, and recognises Sampo Karjalainen as a Finnish name; the man he is treating must, he assumes, be a compatriot. But when Sampo wakes up, he remembers nothing of who he is, and not a word of any language. Dr Friari arranges for him to be sent to Helsinki, where immersion in his land and his language might raise some spark that will help him recover whoever he used to be.

Marani’s book paints a picture of one man’s struggle against the isolation that comes from having no past, and having no language. Though he is made quite welcome by the people he meets, the Helsinki that Sampo comes to inhabit is a city in the midst of a war, under increasing attack from the Soviets. He has a few acquaintances but only one real friend, Olof Koskela, a radical, charismatic pastor who helps him learn the language and shares with him great tales from the Kalevala, Finland’s national epic, among them the tale of the creation of the magical artefact called the “Sampo.” But the book’s only warmth comes from Irma, a nurse. She takes him to her “memory tree,” a tree where she takes everyone who’s important to her, so that the place might be infused with happy memories that she can call upon whenever she needs them. Irma believes her friendship can help him; he, meanwhile, is repelled by the very idea of intimacy, and when she is posted away to Viipuri (Vyborg) he receives and studies her letters but never manages a reply.

The heart of Sampo’s experience, and everything that’s distinctive about the book, is found in his attempts to master his (new) native language—or, at least, to develop his own version of it. It’s a language with four infinitive forms, with fifteen cases (including the abessive, a case denoting absence), a language, says the Pastor, “which should only be sung”; which Sampo uses in his own way, with no sense of register, mixing Biblical language with vocabulary he has picked up in the bar. That thread of intense language acquisition, more than anything, is the unlikely genius of this book, and in particular Judith Landry’s translation; in the carefully tidied-up voice of a language-less first-person, it weaves syntactical reflections thro

The latest addition to our Reviews Section is a piece by Carley Parsons on Niccolo Ammaniti’s Me and You, which is translated from the Italian by Kylee Doust and available from Black Cat.

Carley Parsons was one of my interns last semester, and has previously interned at Syracuse University Press and Random House. She’s graduating this spring and hoping to find a job in publishing. (HINT.)

Black Cat has published three of Ammaniti’s novels, including I’ll Steal You Away, which was longlisted for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize.

Here’s the opening of Carley’s review:

Outcast for his seemingly baseless anger issues, fourteen-year-old Lorenzo Cumi lies to his worried mother about being invited on a ski trip with the ‘in-crowd’ in order to ease her concerns about him. After seeing how happy and relieved it makes her, Lorenzo can’t bring himself to tell her the truth—“I retreated in defeat, feeling like I had committed a murder.” Beginning with a twenty-four-year old Lorenzo unfolding a letter from his half-sister Olivia in a coffee-shop, the rest of the novella, gives a flashback account of how, ten years earlier, he took the opportunity provided by the lie to hide out in a neglected cellar attached to his family’s apartment building, where he is temporarily freed from the paranoid judgments of the adult world.

The teen-angst, adolescent narrative is not unchartered territory for Italian author Niccolò Ammaniti, whose past novels include I’m Not Scared, a coming-of-age and suspense hybrid narrative, translated into thirty-five languages, and As God Commands, which received Italy’s most prestigious literary award, the Premio Strega. Born in Rome in 1966 to a professor of developmental psychopathology, Ammaniti is often praised for his psychological lucidity and is known for exploring relationships between generation-gapped characters.

Click here to read the full review.

Who hasn’t heard something described as “Machiavellian” before? To me the description has come to mean something that is depraved, evil, despicable, cruel. And of course the mans whose name has become an adjective must be like that too and his book, The Prince, must be filled with unspeakable horrors. That’s how I imagined it anyway. When OneWorld Classics offered me a copy of their new translation of The Prince I was curious enough to want to know whether the reality matched my imagination.

Of course it didn’t. The Prince has got to be one of the dullest well-written books there is. Being a treatise on how to both become a prince and keep your power as a prince, it is straightforwardly calculating. We are talking about power, how to get it, how to use, how to keep it. In the world of Renaissance Italy made up of the shifting alliances of city-states, ruled by families that often made me think “mafia,” this can be a useful little book.

Is there cruelty? Yes. Machiavelli suggests the a prince use only as much cruelty as is necessary to make a point otherwise he will lose the support of the people and find himself in danger of being assassinated and/or overthrown. There certainly is no depravity, but evil, well, I suppose that could be up for debate depending on one’s view of power.

Machiavelli (1469-1527) was your standard Renaissance kind of man. He was interested in music, poetry, theatre, and history and served as a chancery official and diplomat for the city of Florence from 1500-1512 after the Medicis had been (temporarily) ousted from power and Florence established as a Republic. When the Medici’s returned to power, Machiavelli was out of a job. He turned to writing. The Prince was his first book. Written in 1512 (but not published until 1532), he dedicated it to Lorenzo de Medici, Duke of Urbino, hoping the Medici’s would sort out Italy’s problems and maybe provide Machiavelli with some employment in the process. He didn’t get the political employment that he had hoped for, but he was commissioned in 1520 by the Medici Pope Clement VII to write a history of Florence. He finished it just in time in 1526 because a year later the Medicis were overthrown again and a month after that Machiavelli died.

Throughout The Prince Machiavelli uses examples taken from Italian politics and history and when he can’t get it there he scours Roman, Greek and Persian history. He uses these examples to illustrate and provide a sort of proof to his arguments. Here is a prince who used mercenaries in his army and see how ill it went for him. Here is a prince who had his own army and refused to use mercenaries, see what success he had. He was successful because of X, Y, and Z.

Of course there is quite a lot of murder and war involved in attaining and keeping power. For instance, if your arrival at prince is not obtained through heredity, you had to reach the heights through political maneuvering and rising through the ranks of the military. Once the title of prince is yours, it behooves you, says Machiavelli, to kill every member of the ousted ruling family. If you do not, it is only a matter of time before the few surviving members gather enough power back to themselves and end your reign. And of course once you are a prince, you might have to make an example of someone from time to time just to remind everyone who is in charge. And then there is the matter of strategic alliances and going to war to get more property. Because when it comes down to it, a prince’s real job is the military. One must either be leading his men out to war or preparing his men for war should you be lucky enough to have some peace.

Perhaps it should be of no surprise that even though the book is about being a prince, there were things that rang out now and then as sounding very corporate. And why not? I suppose in America at least, the heads of large corporations act like princes and while there may only be metaphorical wars and murders, companies get “taken over” and people get “axed” all the time. And tell me if this doesn’t sound like something you’ve experienced at work before:

And it should be borne in mind that there is nothing more difficult to arrange, nor more doubtful of success, nor more dangerous to carry out, than to be the master and introduce new procedures; because he who introduces them makes enemies of those who benefited from the old order, while all those who would benefit from the new measures will be lukewarm in supporting him. This lack of enthusiasm comes partly from their fear of their adversaries, who have the law on their side, and partly from men’s lack of faith, since men do not really put any trust in new things until they have experienced them; so it comes about that any time one’s enemies have an opportunity to attack, they do so with a partisan spirit, while the defenders have no enthusiasm, with the result that they, together with their prince, are endangered.

Or how about this less bloodthirsty piece of advice that we can all agree with:

one can never avoid one drawback without running into another; wisdom consists in being able to recognize the kinds of drawbacks and choose the least bad.

Even though my lack of Italian history made reading The Prince a challenge and forced me to constantly rely on the marvelous notes on the text (at the end of the book instead of footnotes, grr), and I am sure my lack also kept me from grasping some of the more nuanced examples, I am still glad I read the book. I finally know what it is about and Machiavelli no longer sits among my personal pantheon of evil crazy people. I must confess, however, that a small part of me is a bit disappointed that I will no longer be able to imagine what twisted atrocities might reside in the book. I’m not sure what that says about me, but there you go.

Posted in Books, Italian Literature, Nonfiction, Reviews

The trouble was that his most immediate model – one whose influence he could not have ignored even if he had wanted to – was very far from conforming to the new orthodoxies. Ludovico Ariosto’s

The trouble was that his most immediate model – one whose influence he could not have ignored even if he had wanted to – was very far from conforming to the new orthodoxies. Ludovico Ariosto’s