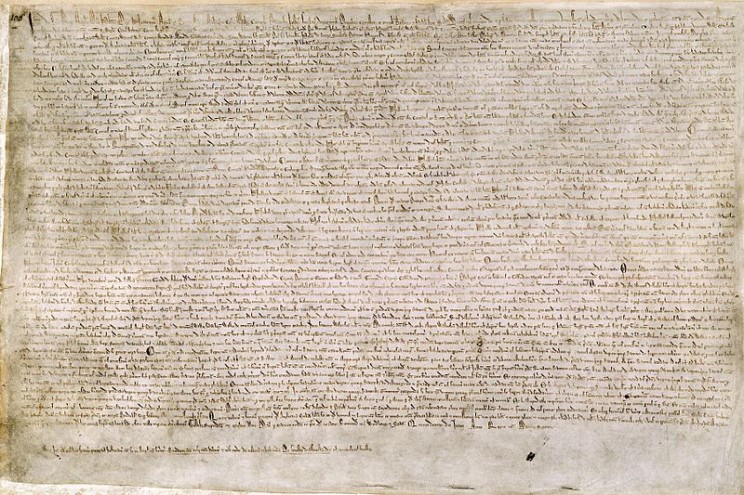

This year marks the 800th anniversary of one of the most famous documents in history, the Magna Carta. Nicholas Vincent, author of Magna Carta: A Very Short Introduction , tells us 10 things everyone should know about the Magna Carta.

The post 10 things you need to know about the Magna Carta appeared first on OUPblog.

On his recent visit to Kenya, President Obama addressed the subject of sexual liberty. At a press conference with the Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, he spoke affectingly about the cause of gay rights, likening the plight of homosexuals to the anti-slavery and anti-segregation struggles in the United States.

The post Compassionate law: Are gay rights ever really a ‘non-issue’? appeared first on OUPblog.

The importance of Magna Carta—both at the time it was issued on 15 June 1215 and in the centuries which followed, when it exerted great influence in countries where the English common law was adopted or imposed—is a major theme of events to mark the charter’s 800th anniversary.

The post Magna Carta: the international dimension appeared first on OUPblog.

On 15th June 2015, Magna Carta celebrates its 800th anniversary. More has been written about this document than about virtually any other piece of parchment in world history. A great deal has been wrongly attributed to it: democracy, Habeas Corpus, Parliament, and trial by jury are all supposed somehow to trace their origins to Runnymede and 1215. In reality, if any of these ideas are even touched upon within Magna Carta, they are found there only in embryonic form.

The post The greatest charter? appeared first on OUPblog.

September 2014 marks the tenth anniversary of the publication of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Over the next month a series of blog posts explore aspects of the Dictionary’s online evolution in the decade since 2004. In this post, Henry Summerson considers how new research in medieval biography is reflected in ODNB updates.

Today’s publication of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography’s September 2014 update—marking the Dictionary’s tenth anniversary—contains a chronological bombshell. The ODNB covers the history of Britons worldwide ‘from the earliest times’, a phrase which until now has meant since the fourth century BC, as represented by Pytheas, the Marseilles merchant whose account of the British Isles is the earliest known to survive. But a new ‘biography’ of the Red Lady of Paviland—whose incomplete skeleton was discovered in 1823 in Wales, and which today resides in Oxford’s Museum of Natural History—takes us back to distant prehistory. As the earliest known site of ceremonial human burial in western Europe, Paviland expands the Dictionary’s range by over 32,000 years.

The Red Lady’s is not the only ODNB biography pieced together from unidentified human remains (Lindow Man and the Sutton Hoo burial are others), while the new update also adds the fifteenth-century ‘Worcester Pilgrim’ whose skeleton and clothing are on display at the city’s cathedral. However, the Red Lady is the only one of these ‘historical bodies’ whose subject has changed sex—the bones having been found to be those of a pre-historical man, and not (as was thought when they were discovered), of a Roman woman.

The process of re-examination and re-interpretation which led to this discovery can serve as a paradigm for the development of the DNB, from its first edition (1885-1900) to its second (2004), and its ongoing programme of online updates. In the case of the Red Lady the moving force was in its broadest sense scientific. In this ‘he’ is not unique in the Dictionary. The bones of the East Frankish queen Eadgyth (d.946), discovered in 2008 provide another example of human remains giving rise to a recent biography. But changes in analysis have more often originated in more conventional forms of historical scholarship. Since 2004 these processes have extended the ODNB’s pre-1600 coverage by 300 men and women, so bringing the Dictionary’s complement for this period to more than 7000 individuals.

In part, these new biographies are an evolution of the Dictionary as it stood in 2004 as we broaden areas of coverage in the light of current scholarship. One example is the 100 new biographies of medieval bishops that, added to the ODNB’s existing selection, now provide a comprehensive survey of every member of the English episcopacy from the Conquest to the Reformation—a project further encouraged by the publication of new sources by the Canterbury and York Society and the Early English Episcopal Acta series.

Taken together these new biographies offer opportunities to explore the medieval church, with reference to incumbents’ background and education, the place of patronage networks, or the shifting influence of royal and papal authority. That William Alnwick (d.1449), ‘a peasant born of a low family’, could become bishop of Norwich and Lincoln is, for example, indicative of the growing complexity of later medieval episcopal administration and its need for talented men. A second ODNB project (still in progress) focuses on late-medieval monasticism. Again, some notable people have come to light, including the redoubtable Elizabeth Cressener, prioress of Dartford, who opposed even Thomas Cromwell with success.

Away from religious life, recent projects to augment the Dictionary’s medieval and early modern coverage have focused on new histories of philanthropy—with men like Thomas Alleyne, a Staffordshire clergyman whose name is preserved by three schools—and of royal courts and courtly life. Hence first-time biographies of Sir George Blage, whom Henry VIII used to address as ‘my pig’, and at a lower social level, John Skut, the tailor who made clothes for most of the king’s wives: ‘while Henry’s queens came and went, John Skut remained.’

Alongside these are many included for remarkable or interesting lives which illuminate the past in sometimes unexpected ways. At the lowest social level, such lives may have been very ordinary, but precisely because they were commonplace they were seldom recorded. Where a full biography is possible, figures of this kind are of considerable interest to historians. One such is Agnes Cowper, a Southwark ‘servant and vagrant’ in the years around 1600; attempts to discover who was responsible for her maintenance shed a fascinating light on a humble and precarious life, and an experience shared by thousands of late-Tudor Londoners. Such light falls only rarely, but the survival of sources, and the readiness of scholars to investigate them, have also led to recent biographies of the Roman officers and their wives at Vindolanda, based on the famous ‘tablets’ found at Chesterholm in Northumberland; the early fourteenth-century anchorite Christina Carpenter, who provoked outrage by leaving her cell (but later returned to it), and whose story has inspired a film, a play and a novel; and trumpeter John Blanke, whose fanfares enlivened the early Tudor court and whose portrait image is the only identifiable likeness of a black person in sixteenth-century British art.

While people like Blanke are included for their distinctiveness, most ODNB subjects can be related to the wider world of their contemporaries. A significant component of the Dictionary since 2004 has been an interest in recreating medieval and early modern networks and associations; they include the sixth-century bringers of Christianity to England, the companions of William I, and the enforcers of Magna Carta. Each establishes connections between historical figures, sets the latter in context, and charts how appreciations of these networks and their participants have developed over time—from the works of early chroniclers to contemporary historians. Indeed, in several instances, notably the Round Table knights or the ‘Merrie Men’, it is this (often imaginative) interpretation and recreation of Britain’s medieval past that is to the fore.

The importance of medieval afterlives returns us to the Red Lady of Paviland. His biography presents what can be known, or plausibly surmised, about its subject, alongside the ways in which his bodily remains (and the resulting life) have been interpreted by successive generations—each perceptibly influenced by the cultural as well as scholarly outlook of the day. Next year sees the 800th anniversary of the granting of Magna Carta, a centenary which can be confidently expected to bring further medieval subjects into Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. It is unlikely that the historians responsible will be unaffected by considerations of the long-term significance of the Charter. Nor, indeed, should they be—it is the interaction of past and present which does most to bring historical biography to life.

The post The Oxford DNB at 10: new perspectives on medieval biography appeared first on OUPblog.

By David Bates

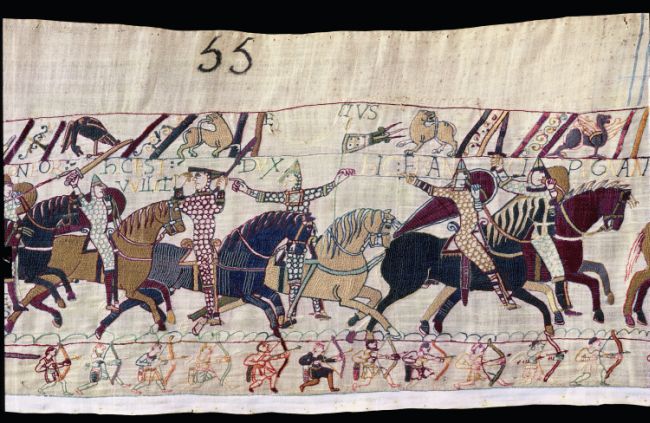

The expansion of the peoples calling themselves the Normans throughout northern and southern Europe and the Middle East has long been one of the most popular and written about topics in medieval history. Hence, although devoted mainly to the history of the cross-Channel empire created by William the Conqueror’s conquest of the English kingdom in 1066 and the so-called loss of Normandy in 1204, I wanted to contribute to these discussions and to the ongoing debates about the impact of this expansion on the histories of the nations and cultures of Europe. That peoples from a region of northern France should become conquerors is one of the apparently inexplicable paradoxes of the subject. The other one is how the conquering Normans apparently faded away, absorbed into the societies they had conquered or within the kingdom of France.

In 1916 Charles Homer Haskins’ made the statement that the Normans represented one of the great civilising influences in European – and indeed world – history. If, a century later, hardly anyone would see it thus, the same imperatives remain, namely to locate the Normans within a context in which it remains popular to write national histories, and, for some, in the midst of debates about the balance of the History curriculum, to see them as being of paramount importance. The history of the Normans cuts across all this, but is an inescapable subject in relation to the histories of the English, French, Irish, Italian, Scottish, and Welsh. Those currently fashionable concepts – and rightly so – ‘The First English Empire’ and ‘European change’ are also at the centre of the debates.

As a concept, empire is nowadays both fashionable and much argued about, a universal phenomenon of human history that has been the subject of several major television programmes. It is a subject that requires a multidisciplinary approach. Over the last two millennia, statements by both contemporaries and subsequent commentators have often set a proclaimed imperial civilising mission as a positive feature against the impact of violence and the social and cultural subjugation of the subjects of an empire. Seen thus, the concept of empire has an obvious relevance to the subject of the Normans. And, in relation to the pan-European expansion of the Normans, and, in particular, to the creation of the kingdom of Sicily, the term diaspora, as it is understood in the social sciences, constitutes a persuasive framework of analysis. Taken together, the two terms empire and diaspora create a world in which individuals and communities had to adapt rapidly to new forms of power and cultures and in which identities are multiple, flexible, and often uncertain. For this reason, the telling of life-histories is of central importance rather than simplified notions of social and cultural identity. One consequence must be the abandonment of the currently popular and unhelpful word Normanitas. The core of this book is a history of power, diversity and multiculturalism in the midst of the complexities of a changing Europe.

The use of terms such as hard power, soft power, hegemony, core and periphery, and cultural transfer can be used to frame interpretations of many national histories, including Welsh, Scottish, and Irish, as well as English. The crucial points in all cases are the mixture of engagement with the dominant imperial power and the perpetuation of difference and diversity through the exercise of agency beyond the core. The framework is one that works especially well in relation to the evolving histories of the Welsh kingdoms/principalities and of the kingdom of Scots. It also means that the so-called ‘anarchy’ of 1135 to 1154, the succession dispute between King Stephen and the Empress Matilda becomes a civil war which needs to be set in a cross-Channel context and through which there were many continuities. And Magna Carta (1215), of which the eight-hundredth anniversary is fast approaching, becomes a consequence of imperial collapse. However, a focus on England and the British Isles just does not work. Normandy’s centrality to the history of the cross-Channel empire created in 1066 is of basic importance. Both morally and militarily the creation of the cross-Channel empire brought problems of a new kind that were for some living, or mainly domiciled, in Normandy a source of anguish. The book’s cover has indeed been chosen with this in mind. It shows troubled individuals who have narrowly escaped disaster at sea, courtesy of St Nicholas. But they successfully made the crossing. And so, of course, did the Tournai marble on which they are carved.

Professor David Bates took his PhD at the University of Exeter, and over a professional career of more than forty years, he has held posts in the Universities of Cardiff, Glasgow, London (where he was Director of the Institute of Historical Research from 2003 to 2008), East Anglia, and Caen Basse-Normandie. He has worked extensively in the archives and libraries of Normandy and northern France and has always sought to emphasise the European dimension to the history of the Normans. ‘He currently holds a Leverhulme Trust Emeritus Fellowship to enable him to complete a new biography of William the Conqueror in the Yale University Press English Monarchs series. His latest book is The Normans and Empire.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Section of the Bayeaux Tapestry, courtesy of the Conservateur of the Bayeux Tapestry. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post The Normans and empire appeared first on OUPblog.