Fannie Farmer’s Food and Cookery for the Sick and Convalescent and Robin Bellinger’s “Feed a Fever, Starve a Cold” inspired my latest New York Times Magazine mini-column.

Sometimes (rarely, but sometimes) when you’re sick you need something other than a hot toddy.

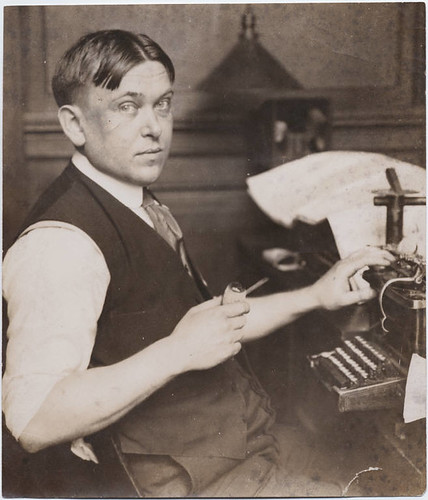

My latest New York Times Magazine columnlet draws on a passage from H.L. Mencken’s The American Language (1921) about the word “bug.”

“An Englishman,” he says, restricts its use “very rigidly to the Cimex lectularius, or common bed-bug, and hence the word has highly impolite connotations. All other crawling things he calls insects. An American of my acquaintance once greatly offended an English friend by using bug for insect. The two were playing billiards one summer evening in the Englishman’s house, and various flying things came through the window and alighted on the cloth. The American, essaying a shot, remarked that he had killed a bug with his cue. To the Englishman this seemed a slanderous reflection upon the cleanliness of his house.”

In a footnote, Mencken elaborates: “Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Gold Bug’ is called ‘The Golden Beetle’ in England. Twenty-five years ago an Englishman named Buggey, laboring under the odium attached to the name, had it changed to Norfolk-Howard, a compound made up of the title and family name of the Duke of Norfolk. The wits of London at once doubled his misery by adopting Norfolk-Howard as a euphemism for bed-bug.”

In a footnote, Mencken elaborates: “Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Gold Bug’ is called ‘The Golden Beetle’ in England. Twenty-five years ago an Englishman named Buggey, laboring under the odium attached to the name, had it changed to Norfolk-Howard, a compound made up of the title and family name of the Duke of Norfolk. The wits of London at once doubled his misery by adopting Norfolk-Howard as a euphemism for bed-bug.”

Even today, slang guru Jonathon Green confirmed when I asked him on Twitter, the UK “does use ‘bedbug’ but otherwise, I would say UK still mainly [uses] ‘insect.’” A British friend of mine agrees, but says of the Mencken passage, “nowadays bug has no connotations of uncleanliness, it’s just not used. The only time an English person says bug to mean insect is ‘don’t let the bedbugs bite’ and no modern British person’s ever had bedbugs, so it’s just a saying, not an insult! We know that it’s a general American term for insect, but we tend to call insects by their species, generally — fly, beetle, ladybird, etc — or, if we need a catch-all euphemism, we’ll say ‘creepy-crawly’ or in Scotland ‘beastie’ (or ‘wee beastie’).”

As the plague spreads, visitors to the UK may wish to make linguistic adjustments.

My latest New York Times Magazine mini-column is on London’s taxi drivers, who memorize 25,000 streets and 20,000 landmarks to obtain a license; they emerge from the training with a larger hippocampus. In the smaller city of his day, Charles Dickens also mastered the roads — to avoid being overcharged. But eventually, as he explains in an essay published in 1860 in All the Year Round, an interview with one man left him with “a more charitable view of the business and trials of cab-driving.”

My wife, accompanied by a servant, and our first-born, an infant, aged three months, had started, one November afternoon, to visit a relative at the other side of London. The day was misty, but when the evening came, the whole town was filled with a dense fog, as thick as soup. I gave them up at an early hour, never supposing that they would attempt to break through the black smoky barrier, and accomplish a journey of nearly nine miles. In this I was mistaken, for towards eleven o’clock the door-bell rang, and they presented themselves muffled up like stage-coachmen. The account I received was, that a four-wheeled cab had been found, that they had been three hours and a half upon the road, that the cabman had walked nearly the whole way with a lamp at the head of his horse, and that he was now outside awaiting payment.

I felt a powerful struggle going on within me. The legislature had fixed the price of cab-work at two shillings an hour, or sixpence a mile, but it had said nothing about snowstorms, fluctuations in the price of provender, or November fogs. There was no contract between my wife and the cabman, and she had not engaged him by the hour, so that, protected by the Act of Parliament, I might have sent out four-and-sixpence for the nine miles’ ride by the servant, and have closed the door securely against the driver. Actuated, perhaps, as much by curiosity, as a sense of justice, I did not do this, but ordered the man in, and gave him the dangerous permission to name his own price. He was a middle-aged driver, with a sharp nose, and when he entered the room, he placed his hat upon the floor, and seemed a little bewildered by novelty of his situation.

“If I am to, I am,” he said,” but I’d my rather leave it to you, sir.”

“This is a journey,” I replied, “hardly within the meaning of the act, and whatever you charge, I will cheerfully pay.”

“Well,” he said, with much deliberation, “I don’t think five shillin’s ought to hurt you?”

As you probably know if you encountered any news source of any kind last week, February 7 was the 200th anniversary of Dickens’ birth. In honor of the occasion, the Guardian filmed Simon Callow on Dickens’ London, the British Council sponsored a readathon, A.N. Devers

I’m behind on everything around here, even linking to my New York Times Magazine mini-columns. Recently I’ve written about: plans to turn the old Miami Herald building into a casino; the (partial) realization of Ray Bradbury’s dream of robot teachers; and, courtesy of Madeline Miller and Plato, The Iliad as love story between Achilles and his man Patroclus.

Bradbury’s comments about robot teachers appeared in a 1974 letter to Brian Sibley. And his short story, “I Sing the Body Electric,” about a girl and her electric grandmother, inspired one of my favorite old Twilight Zone episodes — favorite even though it gave me nightmares — and a mini-series (clip above).