new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: nuclear weapons, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 10 of 10

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: nuclear weapons in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Yasmin Coonjah,

on 9/17/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Politics,

Hillary Clinton,

nuclear war,

Donald Trump,

nuclear weapons,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

national security,

Louis René Beres,

international law,

nuclear crisis,

nuclear proliferation,

2016 presidential election,

anti-proliferation,

July 2015 Vienna Pact,

WMD terrorism,

Add a tag

Plainly, whoever is elected president in November, his or her most urgent obligations will center on American national security. In turn, this will mean an utterly primary emphasis on nuclear strategy. Moreover, concerning such specific primacy, there can be no plausible or compelling counter-arguments. In world politics, some truths are clearly unassailable. For one, nuclear strategy is a "game" that pertinent world leaders must play, whether they like it, or not.

The post America’s nuclear strategy: core obligations for our next president appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Clare Hanson,

on 10/11/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Politics,

atomic bomb,

britain,

Nuclear Power,

nuclear weapons,

Labour Government,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

Clement Attlee,

labour party,

John Baylis,

Kristan Stoddart,

Jeremy Corbyn,

international control agreement,

Add a tag

As the new leader of the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn, wrestles with his own beliefs about nuclear weapons and those opposing beliefs of many members of the Shadow Cabinet, it is interesting to look back to the debates which took place in the Labour Government of Clement Attlee in the immediate post-war period.

The post Clement Attlee and the bomb appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Hannah Paget,

on 7/20/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Arts & Humanities,

hedonic normalization,

K. Eric Drexler,

Nicholas Agar,

Peter Diamandis,

radical optimist,

Sceptical Optimist,

Techno-optimist,

technological progress,

Books,

Sociology,

Technology,

star trek,

Philosophy,

happiness,

climate change,

nuclear weapons,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

well being,

Add a tag

Today there are high hopes for technological progress. Techno-optimists expect massive benefits for humankind from the invention of new technologies. Peter Diamandis is the founder of the X-prize foundation whose purpose is to arrange competitions for breakthrough inventions.

The post Why a technologically enhanced future will be less good than we think appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Clare Hanson,

on 4/10/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

British,

Trident,

nuclear weapons,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

UK General Election 2015,

British national security,

British Nuclear Experience,

John Baylis,

Kristan Stoddart,

Political Leadership and Nuclear Weapons,

Political Party,

Books,

Sociology,

Politics,

Add a tag

The beliefs of British Prime Ministers since 1941 about the nation’s security and role in the world have been of critical importance in understanding the development and retention of a nuclear capability. Winston Churchill supported the development as a means of national survival during the Second World War.

The post Britain, political leadership, and nuclear weapons appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Catherine Fehre,

on 1/12/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Carl von Clausewitz,

deterrence,

Nuclear Question in the Middle East,

Principles of War,

Books,

war,

Politics,

jerusalem,

Middle East,

israel,

Iran,

Defense,

palestine,

nuclear weapons,

synergy,

*Featured,

Louis René Beres,

Sun Tzu,

The Art of War,

Palestinian state,

Add a tag

“Defensive warfare does not consist of waiting idly for things to happen. We must wait only if it brings us visible and decisive advantages. That calm before the storm, when the aggressor is gathering new forces for a great blow, is most dangerous for the defender.”

–Carl von Clausewitz, Principles of War (1812)

For Israel, long beleaguered on many fronts, Iranian nuclear weapons and Palestinian statehood are progressing at approximately the same pace. Although this simultaneous emergence is proceeding without any coordinated intent, the combined security impact on Israel will still be considerable. Indeed, this synergistic impact could quickly become intolerable, but only if the Jewish State insists upon maintaining its current form of “defensive warfare.”

Iran and Palestine are not separate or unrelated hazards to Israel. Rather, they represent intersecting, mutually reinforcing, and potentially existential perils. It follows that Jerusalem must do whatever it can to reduce the expected dangers, synergistically, on both fronts. Operationally, defense must still have its proper place. Among other things, Israel will need to continually enhance its multilayered active defenses. Once facing Iranian nuclear missiles, a core component of the synergistic threat, Israel’s “Arrow” ballistic missile defense system would require a fully 100% reliability of interception.

There is an obvious problem. Any such needed level of reliability would be unattainable. Now, Israeli defense planners must look instead toward conceptualizing and managing long-term deterrence.

Even in the best of all possible strategic environments, establishing stable deterrence will present considerable policy challenges. The intellectual and doctrinal hurdles are substantially numerous and complex; they could quite possibly become rapidly overwhelming. Nonetheless, because of the expectedly synergistic interactions between Iranian nuclear weapons and Palestinian independence, Israel will soon need to update and further refine its overall strategy of deterrence.

Following the defined meaning of synergy, intersecting risks from two seemingly discrete “battle fronts,” or separate theatres of conflict, would actually be greater than the simple sum of their respective parts.

One reason for better understanding this audacious calculation has to do with expected enemy rationality. More precisely, Israel’s leaders will have to accept that certain more-or-less identifiable leaders of prospectively overlapping enemies might not always be able to satisfy usual standards of rational behavior.

With such complex considerations in mind, Israel must plan a deliberate and systematic move beyond the country’s traditionally defensive posture of deliberate nuclear ambiguity. By preparing to shift toward more prudentially selective and partial kinds of nuclear disclosure, Israel might better ensure that its still-rational enemies would remain subject to Israeli nuclear deterrence. Over time, such careful preparations could even prove indispensable.

Israeli planners will also need to understand that the efficacy or credibility of the country’s nuclear deterrence posture could vary inversely with enemy judgments of Israeli nuclear destructiveness. In these circumstances, however ironic, enemy perceptions of a too-large or too-destructive Israeli nuclear deterrent force, or of an Israeli force that is plainly vulnerable to first-strike attacks, could undermine this posture.

Israel’s adversaries, Iran especially, must consistently recognize the Jewish State’s nuclear retaliatory forces as penetration capable. A new state of Palestine would be non-nuclear itself, but could still present an indirect nuclear danger to Israel.

Israel does need to strengthen its assorted active defenses, but Jerusalem must also do everything possible to improve its core deterrence posture. In part, the Israeli task will require a steadily expanding role for advanced cyber-defense and cyber-war.

Above all, Israeli strategic planners should only approach the impending enemy threats from Iran and Palestine as emergently synergistic. Thereafter, it would become apparent that any combined threat from these two sources will be more substantial than the mere arithmetic addition of its two components. Nuanced and inter-penetrating, this prospectively combined threat needs to be assessed more holistically as a complex adversarial unity. Only then could Jerusalem truly understand the full range of existential harms now lying latent in Iran and Palestine.

Armed with such a suitably enhanced understanding, Israel could meaningfully hope to grapple with these unprecedented perils. Operationally, inter alia, this would mean taking much more seriously Carl von Clausewitz’s early warnings on “waiting idly for things to happen.” Interestingly, long before the Prussian military theorist, ancient Chinese strategist Sun-Tzu had observed in The Art of War, “Those who excel at defense bury themselves away below the lowest depths of the earth. Those who excel at offense move from above the greatest heights of Heaven. Thus, they are able to preserve themselves and attain complete victory.”

Unwittingly, Clausewitz and Sun-Tzu have left timely messages for Israel. Facing complex and potentially synergistic enemies in Iran and Palestine, Jerusalem will ultimately need to take appropriate military initiatives toward these foes. More or less audacious, depending upon what area strategic developments should dictate, these progressive initiatives may not propel Israel “above the greatest heights of Heaven,” but they could still represent Israel’s very best remaining path to long-term survival.

Headline image credit: Iranian Missile Found in Hands of Hezbollah by Israel Defense Forces (IDF). CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Ominous synergies: Iran’s nuclear weapons and a Palestinian state appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 4/19/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

war,

Current Affairs,

cold war,

terrorism,

public health,

nuclear weapons,

Barry S. Levy,

social injustice,

ICAN,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

Highly-enriched uranium,

Nuclear Weapons Convention,

Victor W. Side,

Add a tag

By Barry S. Levy and Victor W. Sidel

Out of sight. Out of mind.

Nine countries, mainly the United States and Russia, possess 17,000 nuclear weapons, many of which are hundreds of times more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki almost 70 years ago. An attack and counterattack in which fewer than 1% of these nuclear weapons were detonated could cause tens of millions of deaths and could disrupt climate globally, leading to crop failures and widespread famine. A greater conflagration could cause a “nuclear winter” and threaten the future of life on earth.

The recent tensions concerning Ukraine demonstrate that although 23 years have elapsed since the end of the Cold War, nuclear weapons remain a clear and present danger to humanity. Persistent threats include accidental launch of nuclear warheads, proliferation of nuclear weapons among nations, potential acquisition and use of nuclear weapons by non-state actors, and diversion of human and financial resources in order to maintain and modernize nuclear arsenals in the United States and other nations.

Despite safeguards, accidental detonation remains a real possibility. A few years ago, a US Air Force plane transported six missiles tipped with nuclear warheads, unbeknownst to the pilot and crew. Twice, in recent weeks, it was revealed that as many as half of navy and air force personnel who maintain nuclear-armed missiles and would be responsible for launching them if commanded to do so had cheated on their competency examinations. In 1995, Boris Yeltsin, then president of Russia, had only a few minutes to decide whether to launch Russian nuclear-armed missiles against the United States in response to what, on radar, looked like a US air attack with multiple re-entry vehicles (MERVs); it turned out to be a rocket launched by a team of Norwegian and US scientists to study the aurora borealis.

Another major concern is that the leaders of the nine nations that possess nuclear weapons each have absolute authority — unchecked by other government officials or institutions, even in the United States — to launch an offensive or allegedly defensive nuclear strike.

Furthermore, proliferation remains a serious threat. During the past decade North Korea obtained nuclear technology and fissile materials, and developed and tested one or more nuclear weapons. At least until recently, Iran apparently was — and may still be — on the path to developing nuclear weapons. Given the widespread knowledge about nuclear technology and the potential availability of fissile material, non-state actors could acquire and use nuclear weapons.

U.S. Air Force Staff Sgt. Betty Puma, from the 5th Munitions Squadron, reviews a nuclear weapons maintenance procedures checklist as part of the Nuclear Surety Inspection (NSI) May 19, 2009, at Minot Air Force Base, N.D. An NSI is designed to evaluate a unit’s readiness to execute nuclear operations. Areas to be evaluated during the NSI include operations, maintenance, security and support activities needed to ensure the wing performs its mission in a safe, secure and reliable manner. This no-notice inspection is expected to conclude May 22. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Miguel Lara III/Released). defenseimagery.mil

Highly-enriched uranium (HEU) — the fissile material used in nuclear weapons — is distributed globally, and used in nuclear reactors to perform research or power aircraft carriers and submarines. Converting to low-enriched uranium would eliminate the possibility of HEU being stolen or otherwise diverted to produce nuclear weapons.

Yet another major concern is the huge diversion of financial resources to maintain and modernize the US nuclear weapons arsenal, estimated over the next 30 years to be about $1 trillion. The proposed nuclear weapons budget of the US Department of Energy for fiscal year 2015 is higher than at any time during the Cold War. Meanwhile, substantial cuts have been proposed in programs to dismantle and prevent proliferation of nuclear weapons — and in programs to reduce poverty and protect human rights.

To most Americans, all of these concerns are out of sight and out of mind. Each of us has a responsibility to become more educated about these issues, increase the awareness of other people about them, and advocate for measures to reduce the dangers associated with nuclear weapons, including the abolition of nuclear weapons.

A longstanding proposal to eliminate all nuclear weapons is the Nuclear Weapons Convention (NWC). In 1997, a consortium of experts in law, science, public health, disarmament, and negotiation drafted a model convention. The Convention would require nations that possess nuclear weapons to destroy them in stages — taking them from high-alert status, removing them from deployment, removing warheads from delivery vehicles, disabling warheads by removing explosive “pits,” and placing fissile material under control of the United Nations. Such a convention has had wide public support throughout the world.

An immediate step that could pave the way to the Nuclear Weapons Convention and the eradication of nuclear weapons is a treaty banning nuclear weapons. Such a treaty could be negotiated with or without the participation of those nations possessing nuclear weapons. It could create an international norm of the illegality of nuclear weapons, similar to the norms that have been established concerning chemical and biological weapons, antipersonnel landmines, and cluster munitions. Such a treaty could put substantial pressure on the nations possessing nuclear weapons to comply with their disarmament obligations — which they have been unwilling to do thus far. The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) has mobilized 300 civil-society organizations in 90 countries to campaign, on humanitarian grounds, for such a treaty banning nuclear weapons.

Given resurgent Cold-War-era arguments for revitalizing US nuclear-weapons capabilities to deter Russian actions in Ukraine, we must resist measures that would reset the “Doomsday Clock” to a point that places all humanity — and indeed all life on earth — in great peril of annihilation by nuclear weapons.

Barry S. Levy, M.D., M.P.H., and Victor W. Sidel, M.D., are co-editors of the recently published second edition of Social Injustice and Public Health as well as two editions each of the books War and Public Health and Terrorism and Public Health, all of which have been published by Oxford University Press. They are both past presidents of the American Public Health Association. Dr. Levy is an Adjunct Professor of Public Health at Tufts University School of Medicine. Dr. Sidel is Distinguished University Professor of Social Medicine Emeritus at Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein Medical College and an Adjunct Professor of Public Health at Weill Cornell Medical College. Victor W. Sidel was a member of the 1997 consortium of experts in law, science, public health, disarmament, and negotiation that drafted the model Nuclear Weapons Convention. Read their previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The continuing threat of nuclear weapons appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ChloeF,

on 2/22/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Affairs,

South Korea,

Korea,

VSI,

Asia,

missile,

bomb,

North Korea,

nuclear,

nuclear weapons,

Korean War,

korea’s,

nuclear program,

*Featured,

regime,

VSIs,

missiles,

ballistic missiles,

ICBM,

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles,

Joseph M. Siracusa,

Joseph Siracusa,

nucelar,

Pyongyang,

very short introductons,

weaponry,

pyongyang’s,

Add a tag

By Joseph M. Siracusa

Any discussion of North Korea’s nuclear program should begin with an understanding of the limited information available regarding its development. North Korea has been very effective in denying external observers any significant information on its nuclear program. As a result, the outside world has had little direct evidence of the North Korean efforts and has mainly relied on indirect inferences, leaving substantial uncertainties.

Moreover, because its nuclear weapons program wasn’t self-contained, it has been especially difficult to determine how much external assistance arrived and from where, and to assess the program’s overall sophistication.

That said, what is known is that Pyongyang has tested three nuclear devices: in 2006, 2009, and, of course most recently, on 12 February 2013. They have all had varying degrees of success, and North Korea has put considerable effort into developing and testing missiles as possible delivery vehicles.

February’s detonation of a “smaller and light” nuclear device — presumably, part of the plan to build a small atomic weapon to mount on a long-range missile — was the first test carried out by Kim Jong Eun, the young, third-generation leader, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather. And while it always intriguing to speculate on who is running the show in North Korea, the finger generallyseems to point to the military.

Many foreign observers have come to believe the otherwise desperate, hungry population (and failing regime?) that make up North Korea’s secretive police state is best symbolized by its nuclear and missile programs. Which gives rise to the basic question: what, then, is Pyongyang’s motivation for its nuclear and missile programs? Is it, as Victor Cha once asked, for swords, shields, or badges?

In other words, are the programs intended to provide offensive weapons, defensive weapons, or symbols of status? In spite of prolonged diplomatic negotiations with Pyongyang officials over the past two decades, the question of motivation remains elusive.

Pyongyang’s interest in obtaining nuclear weaponry, beginning around the mid-1950s, has apparently stemmed in part from what it perceived as the US’s nuclear threats and concerns about the nuclear umbrella that protects South Korea. These threats, in turn, have pervaded North Korean strategic thought and action since the Korean War.

These actions may be gauged as offensive or defensive, but Pyongyang officials were at one point fearful of South Korea’s nuclear ambitions and later uncertain about the US emphasis on tactical nuclear weapons and its nuclear “first use” policy in defense of the South. These nuclear-armed additions included 280mm artillery shells, rockets, cruise missiles, and mines.

Against this backdrop, all of North Korea’s nuclear activities tend to focus on a single goal: preservation of the regime. Possessing nuclear weapons would diminish the US’s threat to the nation’s independence, but it could also reduce Pyongyang’s dependence upon China for its security.

Against this backdrop, all of North Korea’s nuclear activities tend to focus on a single goal: preservation of the regime. Possessing nuclear weapons would diminish the US’s threat to the nation’s independence, but it could also reduce Pyongyang’s dependence upon China for its security.

North Korean officials, too, may feel that a small nuclear force offers some insurance against South Korea’s dynamic economic growth and its eventual conventional military superiority.

Pyongyang undoubtedly views its burgeoning nuclear arsenal as a symbol of the regime’s legitimacy and status, which would assist in keeping the Stalinist dynasty in power. Additionally enhanced status would, of course, assist in gaining diplomatic leverage.

Although the North Koreans have boasted about their nuclear deterrent’s ability to hold the US and it allies at bay, it is fairly clear that North Korea has vastly overstated its ability to strike, in part because of the limited amount of fissile material available to Pyongyang and also because of its inability to field a credible delivery option for its nuclear weapons.

The North Koreans have launched long-range ballistic missiles in 1998, 2006, 2009, and 2012, with limited success. By comparison, the US test fires its new missiles scores of times to ensure that they are operationally effective. North Korea would need many more tests of all the systems, independently and together, at a much higher rate than one every few years, to have confidence the missile would even leave the launch pad, let alone approach a target with sufficient accuracy to destroy it.

This was dramatically demonstrated on 13 April 2012, by the failure of the much-hyped effort to employ a three-stage missile, which would send a satellite into space. If the missile was, as Washington and Tokyo believed, a disguised test of an ICBM, the fact that it crashed into the sea shortly after launch illustrated that North Korea’s development and testing of missiles as possible delivery vehicles had miles to go.

Joseph M. Siracusa is Professor in Human Security and International Diplomacy and Associate Dean of International Studies, at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Melbourne, Australia. Among his numerous books are included: Nuclear Weapons: A Very Short Introduction (2008) and A Global History of the Nuclear Arms Race: Weapons, Strategy, and Politics, 2 vols., with Richard Dean Burns (2013).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

Image credit: North Korea Theater Missile Threats, By Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS.) Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post North Korea and the bomb appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/23/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Affairs,

israel,

Iran,

nuclear weapons,

*Featured,

Louis René Beres,

Law & Politics,

Tehran,

General Moshe Dayan,

John T. Chain,

Add a tag

By Professor Louis René Beres and General John T. Chain (USAF/ret.)

In world politics, irrational does not mean “crazy.” It does mean valuing certain goals or objectives even more highly than national survival. In such rare but not unprecedented circumstances, the irrational country leadership may still maintain a distinct rank-order of preferences. Unlike trying to influence a “crazy” state, therefore, it is possible to effectively deter an irrational adversary.

Iran is not a “crazy,” or wholly unpredictable, state. Although it is conceivable that Iran’s political and clerical leaders could sometime welcome the Shiite apocalypse more highly than avoiding military destruction, they could also remain subject to alternative deterrent threats. Faced with such circumstances, Israel could plan on basing stable and long-term deterrence of an already-nuclear Iran upon various unorthodox threats of reprisal or punishment. Israel’s only other fully rational option could be a prompt and still-purposeful preemption.

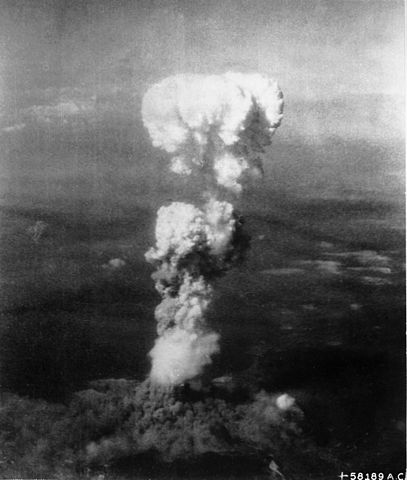

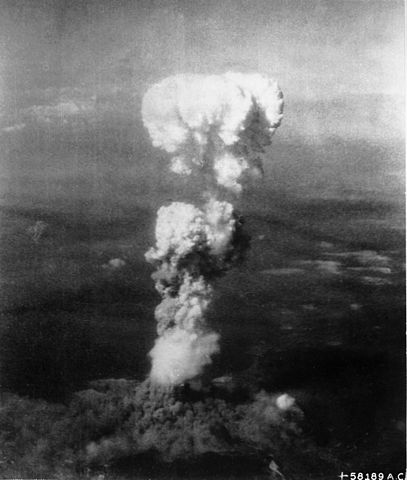

At the time this photo was made, smoke billowed 20,000 feet above Hiroshima while smoke from the burst of the first atomic bomb had spread over 10,000 feet on the target at the base of the rising column (6 August 1945).

Today, a nuclear Iran appears almost a

fait accompli. For Israel, soon to be deprived of any cost-effective preemption options, this means forging a strategy to coexist or “live with” a nuclear Iran. Such an essential strategy of nuclear deterrence would call for reduced ambiguity about certain of its strategic forces; enhanced and partially disclosed nuclear targeting options; substantial and partially disclosed programs for active defenses; recognizable steps to ensure the survivability of its nuclear retaliatory forces; and, to bring all of these elements together in a coherent mission plan, a comprehensive strategic doctrine.

Additionally, because of the prospect of Iranian irrationality, Israel’s military planners will have to identify suitable ways of ensuring that even a nuclear “suicide state” could be deterred. Such a perilous threat may be very small, but, with Iran’s particular Shiite eschatology, it might not be negligible. And while the probability of having to face such an irrational enemy state would probably be very low, the disutility or expected harm of any single deterrence failure could be very high.

Israel needs to maintain and strengthen its plans for ballistic missile defense, both the Arrow system, and also Iron Dome, a lower-altitude interceptor designed to guard against shorter-range rocket attacks from Lebanon and Gaza. These systems, including Magic Wand, which is still in the development phase, will inevitably have leakage. It follows that their principal benefit would ultimately lie in enhanced deterrence, rather than in any added physical protection.

A newly-nuclear Iran, if still rational, would need steadily increasing numbers of offensive missiles in order to achieve a sufficiently destructive first-strike capability against Israel. There could come a time, however, when Iran would be able to deploy more than a small number of nuclear-tipped missiles. Should that happen, Arrow, Iron Dome and, potentially, Magic Wand, could cease being critical enhancements of Israeli nuclear de

By: Lauren,

on 11/3/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Africa,

Middle East,

nuclear war,

United Nations,

Military,

israel,

Iran,

nuclear weapons,

What Everyone Needs To Know,

*Featured,

Louis René Beres,

nuclear energy,

nuclear missiles,

Add a tag

The United States, preemption, and international law

By Professor Louis René Beres

Admiral Leon “Bud” Edney

General Thomas G. McInerney

For now, the “Arab Spring” and its aftermath still occupy center-stage in the Middle East and North Africa. Nonetheless, from a regional and perhaps even global security perspective, the genuinely core threat to peace and stability remains Iran. Whatever else might determinably shape ongoing transformations of power and authority in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria and Saudi Arabia, it is apt to pale in urgency beside the steadily expanding prospect of a nuclear Iran.

Enter international law. Designed, inter alia, to ensure the survival of states in a persistently anarchic world – a world originally fashioned after the Thirty Years War and the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 – this law includes the “inherent” right of national self-defense. Such right may be exercised not only after an attack has already been suffered, but, sometimes, also, in advance of an expected attack.

What can now be done, lawfully, about relentless Iranian nuclear weapons development? Do individual states, especially those in greatest prospective danger from any expressions of Iranian nuclear aggression, have a legal right to strike first defensively? In short, could such a preemption ever be permissible under international law?

For the United States, preemption remains a part of codified American military doctrine. But is this national doctrine necessarily consistent with the legal and complex international expectations of anticipatory self-defense?

To begin, international law derives from multiple authoritative sources, including international custom. Although written law of the UN Charter (treaty law) reserves the right of self-defense only to those states that have already suffered an attack (Article 51), equally valid customary law still permits a first use of force if the particular danger posed is “instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means and no moment for deliberation.” Stemming from an 1837 event in jurisprudential history known as the Caroline, which concerned the unsuccessful rebellion in Upper Canada against British rule, this doctrine builds purposefully upon a seventeenth-century formulation of Hugo Grotius.

Self-defense, says the classical Dutch scholar in, The Law of War and Peace (1625), may be permitted “not only after an attack has already been suffered, but also in advance, where the deed may be anticipated.” In his later text of 1758, The Right of Self-Protection and the Effects of Sovereignty and Independence of Nations, Swiss jurist Emmerich de Vattel affirmed: “A nation has the right to resist the injury another seeks to inflict upon it, and to use force and every other just means of resistance against the aggressor.”

Article 51 of the UN Charter, limiting self-defense to circumstances following an attack, does not override the customary right of anticipatory self-defense. Interestingly, especially for Americans, the works of Grotius and Vattel were favorite readings of Thomas Jefferson, who relied heavily upon them for crafting the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America.

We should also recall Article VI of the US Constitution, and assorted US Supreme Court decisions. These proclaim, straightforwardly, that international law is necessarily part of the law of the United States.

The Caroline notes an implicit distinction between preventive war (which is never legal), and preemptive war. The latter is not permitted merely to protect oneself against an emerging threat, but only when the danger posed is “instant” and

By: Michelle,

on 1/25/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Media,

Middle East,

israel,

Iran,

Council on Foreign Relations,

WikiLeaks,

nuclear weapons,

uranium,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Dana Allin,

International Institute for Strategic Studies,

Iran nuclear crisis,

Steve Simon,

The Sixth Crisis,

iran’s,

Politics,

Current Events,

Add a tag

By Dana H. Allin and Steven Simon

The Wikileaks trove of diplomatic documents confirms what many have known for a long time: Israel is not the only Middle Eastern country that fears a nuclear armed Iran and wants Washington to do something about it.

If Tehran was listening, the truth of this fear was apparent last month in Bahrain, where the International Institute for Strategic Studies organized a large meeting of Gulf Arab ministers, King Abdullah of Jordan, Iran’s foreign minister Mottaki, and top officials from outside powers including Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. The convocation was polite: no one said it was time to “cut off the head of the snake,” as Saudi Arabia’s King was reported, in one of the Wikileaks cables, to have urged in regard to Iran. But Arab anxiety about Iran’s power, and how it could be augmented by nuclear power, was palpable.

As one might also expect, the closer Arab capitals are to Iran, apart from Baghdad, the more fervently their rulers implore Washington to take vigorous action – up to and including military action – against Iranian nuclear facilities. Some, like Saudi Arabia, have offered to make up for Iran’s lost oil production in the event of war to limit the adverse effect of higher prices on a weak US economy. In those countries closest to Iran, moreover, the Arab street shares regimes’ worries. In a poll last year in Saudi Arabia, 40 % of respondents in three large cities said that the US should bomb Iran, while one out of four said that it would be OK with them if even Israel did the job. The governments of countries farther away but within range of Iran’s Shahab 3 missiles – such as Egypt – are also nervous. In an act of not-so-subtle messaging, Egypt has agreed to let nuclear capable Israeli warships through the Suez Canal, so that the Israeli Navy can get to the Persian Gulf quickly. These ships would not be going there for a port visit and shopping at the Sharjah souk.

It should be said that Wikileaks’ reckless disclosures threaten to box in both Washington and its allies in damaging ways. The purpose of secret diplomacy, as opposed to public throat clearing, is to allow governments to express views freely, experiment with positions, and bargain without creating pressures for rash action or causing paralysis. The problem with Wikileaks’ irresponsible revelations is that they complicate diplomatic coordination in matters, literally, of war and peace.

Yet, despite the muddle, there is no reason for Washington to change its basic course. A military option against nuclear facilities will not be ruled out in any event; yet the purpose of US policy should be to forestall the moment when the US must choose whether to disarm Iran or settle for a strategy of containment. The relative weakness of of America’s current position dictates this approach. The United States still has large numbers of troops committed to two wars, faces the possibility of conflict in Korea, and remains mired in the unemployment emergency created by the financial crash and Great Recession. European, American and Russian cohesion on Iran policy is still fragile. In the fullness of time, these debilities can be overcome.

And there is time. To be sure, among the new revelations was an alarming report of Tehran’s cooperation with North Korea to produce more powerful ballistic missiles. Iran now possesses 33 kilograms of uranium enriched to the 20% threshold for highly enriched uranium, as well