By Katherine M. Venables

Occupational epidemiology is one of those fascinating areas which spans important areas of human life: health, disease, work, law, public policy, the economy. Work is fundamental to any society and the importance society attaches to the health of its workers varies over time and between countries. Because of the lessons to be learned by looking at other countries as well as one’s own, occupational epidemiology is a truly global discipline. Emerging economies often prioritize productivity over other issues, but also can learn from the long history of improvement in working conditions which has taken place in developed countries. Looking the other way, the West can learn from fresh insights gained in studies set in low and middle-income countries.

Exposures are usually higher in emerging economies and epidemiological methods are an important tool in detecting and quantifying outbreaks of occupational disease which may have been controlled in the West. A recent study of digestive cancer in a Chinese asbestos mining and milling cohort provides additional evidence that stomach cancer may be associated with high levels of exposure to chrostile asbestos, for example. This was a collaborative study between researchers in China, Hong Kong, Japan, and the United States, and illustrates the way that studying an “old” disease in a new context can provide results which are of global benefit.

Issues in occupational epidemiology are never static. Work exposures change along with materials and processes. The ubiquitous printing industry, for example, is always developing new inks, cleaning agents, and processes. A cluster of cases of the rare liver cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, was noted in Japanese printers and this finding was replicated in the Nordic printing industry by using one of the large Nordic population-based databases. This replication is important because it shows that the association is unlikely to be due to a lifestyle factor specific to Japan.

“Big data” sharpens statistical power and there are now specific data pooling projects in occupational epidemiology, to supplement the use of existing large databases. The SYNERGY study, for example, pools lung cancer case-control studies with the aim of teasing out occupational effects from behind the masking effect of smoking, which remains by far the most important driver for lung cancer. A recent analysis with around 20,000 cases and controls was able to show that bakers are not at increased risk of lung cancer, whereas the many previous smaller studies had given inconsistent results.

“Big data” sharpens statistical power and there are now specific data pooling projects in occupational epidemiology, to supplement the use of existing large databases. The SYNERGY study, for example, pools lung cancer case-control studies with the aim of teasing out occupational effects from behind the masking effect of smoking, which remains by far the most important driver for lung cancer. A recent analysis with around 20,000 cases and controls was able to show that bakers are not at increased risk of lung cancer, whereas the many previous smaller studies had given inconsistent results.

The addition of systematic reviews to the toolkit has strengthened the evidence base in occupational epidemiology, allowing policy about occupational risks and their prevention to be made with confidence. Health economics, also, can be applied to findings from occupational epidemiology to clarify policy issues.

Development brings its own issues to which occupational epidemiology can be applied. We now live longer in the West, and we will have to work into old age, often while carrying chronic diseases. Despite frequently-expressed concerns about an ageing workforce, a recent study in an Australian smelter confirmed others in that the older workers maintained their ability to work safely and the highest injury rates were in young workers. Patients with previously fatal diseases survive into adult life and, potentially, the workforce; a survey of patients with cystic fibrosis, for example, found that disease severity was less important as a predictor of employment than social factors such as educational attainment and locality. A loss of heavy industry in the West, combined with cheap transport, means that many of us spend most of our waking hours sitting down, promoting obesity and its complications. A sample of UK office workers spent 65% of their work time sitting and did not compensate for this by being more active outside work. The economic downturn is a major political and social preoccupation, bringing uncertainty about future employment, which may fuel dysfunctional behaviour such as ‘presenteeism’. A Swedish study suggested that this may be associated with poor mental wellbeing.

Katherine M. Venables is a Reader in the Department of Public Health at the University of Oxford. Her research has always focused on aetiological epidemiology. At Oxford, she has worked on a cohort study of mortality and cancer incidence in military veterans exposed to low levels of chemical warfare agents, and also on the provision of occupational health services to university staff. She is editor of Current Topics in Occupational Epidemiology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Woman smoking a cigarette by Oxfordian Kissuth. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Occupational epidemiology: a truly global discipline appeared first on OUPblog.

By John Cherrie

Each year there are 1,800 people killed on the roads in Britain, but over the same period there are around four times as many deaths from cancers that were caused by hazardous agents at work, and many more cases of occupational cancer where the person is cured. There are similar statistics on workplace cancer from most countries; this is a global problem. Occupational cancer accounts for 5 percent of all cancer deaths in Britain, and around one in seven cases of lung cancer in men are attributable to asbestos, diesel engine exhaust, crystalline silica dust or one of 18 other carcinogens found in the workplace. All of these deaths could have been prevented, and in the future we can stop this unnecessary death toll if we take the right action now.

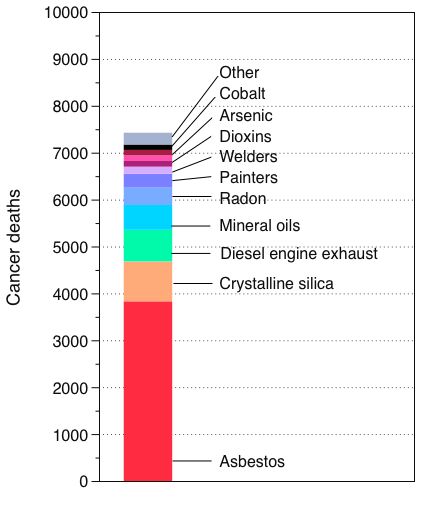

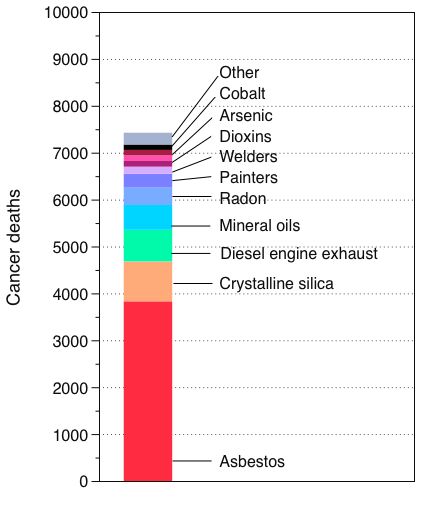

In 2009, I set out some simple steps to reduce occupational exposure to chemical carcinogens. The basis was the recognition that the overwhelming majority of workplace cancers from dusts, gases and vapours are caused by exposure to just ten agents or work circumstances, such as welding and painting (see chart). Focusing our efforts on this relatively short priority list could have a major impact.

Many of these exposures are associated with the construction industry. Almost all are generated as part of a process and are not being manufactured for industrial or consumer uses, e.g. diesel engine exhaust and the dust from construction materials that contain sand (crystalline silica).

The strategies to control exposure to these agents are well understood and so there is no need to invent new technological solutions for this problem. Use of containment, localized ventilation targeted at the source of exposure and other engineering methods can be used to reduce the exposures. If further control is needed then workers can wear personal protective devices, such as respirators, to filter out contaminants before they enter the body.

There are also robust regulations to ensure employers understand their obligations to employees, contractors and members of the public, both in Britain through the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH) Regulations and in the rest of Europe via the Carcinogens and Mutagens Directive.

We know that as time goes on, most exposures in the workplace are decreasing by between about 5% and 10% each year. This seems to be true for many dusts, fibres, gases and vapours, and it is a worldwide trend. There is every reason to believe this is also true for the carcinogenic exposures we are discussing. This means that over a ten-year period the risk of future cancer deaths is may drop by about half. If we could increase the rate of decrease in exposure to 20% per annum then after 10 years the risk of future disease should have decreased by about 90%.

However, during the five years since my article was published, very little has been done to improve controls for carcinogens at work. Recent evidence from the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), the regulator in Britain, shows widespread non-compliance at worksites where there is exposure to respirable crystalline silica. Most people are still unaware of the cancer risks associated with being a painter or a welder and so no effective controls are generally put in place. There have been no effective steps taken to reduce exposure to diesel engine exhaust, or most of the other “top ten” workplace carcinogens. What is the barrier preventing change?

In my opinion, the main issue is that we don’t perceive most of these agents or situations as likely to cause cancer. For example, airborne dust on construction sites, which often contains crystalline silica and may contain other carcinogenic substances, is considered the norm. Diesel soot is ubiquitous in our cities and we all accept it even though it is categorized as a human carcinogen. In my paper I complained that there were ‘no steps taken to reduce the risk from diesel exhaust particulate emission for most exposed groups and no particular priority given to this by regulatory authorities.’ Nothing has changed in this respect. We need an agreed commitment from regulators, employers and workers to change for the better. Perhaps we need to consider requiring traffic wardens to wear facemasks and encourage painters to work in safer healthier ways. At least we should take a fresh look at what can reasonably be done to protect people.

We know that since 2008 the number of road traffic deaths in the United Kingdom has decreased by about a third and downward time trend seems relentless. Road traffic campaigners have envisaged a future of zero harm from motor vehicles. Similarly we know that the level of exposure to most workplace carcinogenic substances is decreasing. Can we not also consider a future world where we have eliminated occupational cancer or at least reduced the health consequences to a tiny fraction of today’s death toll? It will be a future that our children or their children will inhabit because of the long lag between exposure to the carcinogens and the development of the disease, but unless we act the danger is that we never see an end to the problem.

As a first step we need to have en effective campaign to raise awareness of the problem of workplace cancers and to start to change attitudes to the most pernicious workplace carcinogens.

John Cherrie is Research Director at the Institute of Occupational Medicine (IOM) in Edinburgh, UK, and Honorary Professor at the University of Aberdeen. He has been involved in several studies to estimate the health impact from carcinogens in the workplace. He is currently Principal Investigator for a study that will estimate the occupational cancer and chronic non-malignant respiratory disease burden in the constructions sector in Singapore. In 2014 he was awarded the Bedford Medal for outstanding contributions to the discipline of occupational hygiene. He is the author of the paper ‘Reducing occupational exposure to chemical carcinogens‘, which is published in the journal Occupational Medicine.

Occupational Medicine is an international peer-reviewed journal, providing vital information for the promotion of workplace health and safety. Topics covered include work-related injury and illness, accident and illness prevention, health promotion, occupational disease, health education, the establishment and implementation of health and safety standards, monitoring of the work environment, and the management of recognised hazards.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Graph provided by the author. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post How to prevent workplace cancer appeared first on OUPblog.

By Tee L. Guidotti

Mengxi Village, in Zhejiang province, in eastern coastal China, is an obscure rural hamlet not far geographically but far removed socially from the beauty, history, and glory of Hangzhou, the capital. Now it is the unlikely center of a an environmental health awakening in which citizens took direct action by storming the gates of a lead battery recycling plant that has caused lead poisoning among both children and adults in the village. Sharon Lafranierre reported the story on 15 June 2011 in the New York Times.

What was unusual about the incident was not that the community was heavily polluted and that the health of children in the village has been harmed but that local residents, 200 of them, took violent action, smashing property in the plant, and seem not to have been punished for it. The incident opens a window on the rapid change in attitudes in China toward industrialization, pollution, and authority.

Like many rural settlements, Mengxi responded to the opening of the Chinese economy by creating small-scale business to make money and to raise local residents out of poverty. Compared to earlier local “township enterprises,” this plant came late to Mengxi; it was only opened in 2005. But it caught a wave of increased business demand and now employs a reported 1000 workers, making it an important economic support for rural Deqing County. Historically, these township enterprises have been a peculiar and often corrupt blend of local government and local entrepreneurship. They have been grossly undercapitalized and essentially unregulated: the Mengxi battery plant had apparently been knowingly operating for at least six years in violation of environmental emissions standards. The central Government has been cracking down in recent years and making examples in some egregious cases but local authorities are stronger in rural areas.

Local officials, having a deep and usually personal stake in these enterprises, often try harder to protect them than to protect the local people for whom they are responsible. Mengxi illustrates the problem of local officials refusing to act, denying that the problem exists, and suppressing efforts to find out by journalists or by public health experts. Part of this may be greed but once the damage is done fear probably takes over as the main motivation for concealing the truth. Already, eight company officials have been arrested and all must be very aware of the two senior executive and the dairy boss who were executed in China this year for allowing contamination of milk.

Battery plants on this small scale are particularly hazardous and in the absence of effective regulation can be very dangerous to local residents, especially children, who are more vulnerable than adults to lead poisoning. Lead exposure in this situation may occur from airborne dust containing lead, contact with dirt contaminated from larger particles of lead that drop out of the air from fumes, food grown in contaminated soil, dust brought home on the clothes of adults who work in the plants, and even in homes, where some families actually smelt small quantities of lead as a cottage industry. Lead exerts its major toxic effects on the nervous system. In children, it can cause a spectrum of disorders ranging from severe lead poisoning and brain damage (“toxic encephalopathy”) at levels seen in some children in the village to more subtle toxicity that causes a reduction in potential intelligence (difficult to measure in an individual child but demonstrable in a population) and loss of impulse control, which can be seen at levels that are now common throughout China and used to be common in the United States dec

“Big data” sharpens statistical power and there are now specific data pooling projects in occupational epidemiology, to supplement the use of existing large databases. The SYNERGY study, for example, pools lung cancer case-control studies with the aim of teasing out occupational effects from behind the masking effect of smoking, which remains by far the most important driver for lung cancer. A recent analysis with around 20,000 cases and controls was able to show that bakers are not at increased risk of lung cancer, whereas the many previous smaller studies had given inconsistent results.

“Big data” sharpens statistical power and there are now specific data pooling projects in occupational epidemiology, to supplement the use of existing large databases. The SYNERGY study, for example, pools lung cancer case-control studies with the aim of teasing out occupational effects from behind the masking effect of smoking, which remains by far the most important driver for lung cancer. A recent analysis with around 20,000 cases and controls was able to show that bakers are not at increased risk of lung cancer, whereas the many previous smaller studies had given inconsistent results.