new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: w.w. norton, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 12 of 12

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: w.w. norton in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Renowned comics creator Alan Moore has landed a deal for his second prose novel. Liveright, an imprint at W. W. Norton & Company, will publish Jerusalem in Fall 2016.

Renowned comics creator Alan Moore has landed a deal for his second prose novel. Liveright, an imprint at W. W. Norton & Company, will publish Jerusalem in Fall 2016.

According to The New York Times, Moore’s manuscript may contain more than one million words. Moore sets this historical fiction-fantasy story in his hometown of Northampton, England.

Here’s more from The Guardian: “The acclaimed comics writer began work on Jerusalem in 2008 and finished his gargantuan draft last September, as his daughter Leah Moore announced on Facebook. The novel is said to explore the small area of Northampton where Moore grew up, ranging from his own family’s stories to historical events to fantasy, with chapters told in different voices.”

I published three books with Alane Salierno Mason and W.W. Norton years ago, and every now and then, Alane returns—her words on a page, that page slipped inside a book she's been working on.

A few weeks ago,

My Life as a Foreign Country showed up at my door—a new war memoir by

the poet Brian Turner. I had been living a long, solid stretch of distracting diminishings. I had been finding it nearly impossible to read—no time for it, or no energy when the hour was to be had. I had a mile-high stack of other books that had been sent my way, of requests I couldn't get to, of requests I was meeting instead of reading, but something about this one book commanded my attention. I kept clawing my way back to it, read it by half page and full page, by train ride, in a room brightened at 3 AM by a lamp.

Because

My Life breaks the rules, I liked it. Because it reads more like a hallucination than a life. Because Turner doesn't set aside his poetry in writing prose.

Turner's memoir tells us something of his Sergeant years in Iraq, something of the wars his grandfather, father, and uncle fought. He slides in and out of what he remembers and what he conjures—taking the powers of the empathetic imagination to an entirely new realm. He sees the thoughts of the suicide bomber, sings the song of the bomb builder, lives for and maybe beyond the enemy. The dreams are feral and the details are specific, and Sgt Turner is dead, too, but he is writing his death down, he is writing himself into the final page and "there is nothing strange" in all of that.

Earlier this morning (it seems a year ago now) I was finishing a book of my own, responding to final manuscript queries. I was asking myself how one authentically renders shock.

My Life authentically renders shock. It reveals how the terror lives on, how it knocks on the door, how it enters the room, how it watches you sleep with your wife. Years on, the shock does that. The war, Turner tells us, is never done.

The language smears and catches. It sounds like this:

This is part of the intoxication, part of the pathology of it all. This is part of what I was learning, from early childhood on—that to journey into the wild spaces where profound questions are given a violent and inexorable response, that to travail through fire and return again—these are the experiences which determine the making of a man. To be a man, I would need to walk into the thunder and hail of a world stripped of its reason, just as others in my family had done before me. And if I were strong enough, and capable enough, and god-damned lucky enough, I might one day return clothed in an unshakable silence. Back to the world, as they say.

This spring, my creative nonfiction students at Penn will assess and learn from the poetry of Sgt. Turner.

Today we bring you our weekly sampler of cool youth media and marketing gigs. If your company has an open position in the youth media or marketing space, we encourage you to join the Ypulse LinkedIn group, if you haven’t yet, and post there for... Read the rest of this post

As with years past, we’re going to spend the next five weeks highlighting all 25 titles on the BTBA fiction longlist. We’ll have a variety of guests writing these posts, all of which are centered around the question of “Why This Book Should Win.” Hopefully these are funny, accidental, entertaining, and informative posts that prompt you to read at least a few of these excellent works.

Click here for all past and future posts in this series.

Funeral for a Dog by Thomas Pletzinger, translated by Ross Benjamin

Language: German

Country: Germany

Publisher: W.W. Norton

Why This Book Should Win: Two reasons: 1) during Thomas’s reading tour, three consecutive events were disrupted by a streaker, a woman passing out and smashing a glass table, and a massive pillow fight amid a Biblical thunderstorm; 2) the phone number.

The following piece is written by Erin Edmison who is a partner at Edmison/Harper Literary Scouting and worked on Edith Pearlman’s Binocular Vision, which beat out Eugenides & Co. for the NBCC award in fiction.

Thomas Pletzinger is a romantic. He’s not a Romantic; the language of his 2011 debut novel Funeral for a Dog is more observational than emotional, or maybe it’s observational about emotion, in the way of that midcentury German master, Max Frisch (ripples of Montauk lap at this novel’s edge). Then again, Pletzinger’s book feels totally modern (if not Modern). The characters’ central drama has to do with The Way Some of Us Live Now: over-educated, burdened by choice, willing to throw out the cultural roadmaps, but unsure how to draw new ones.

Daniel Mandelkern (his surname translates to “almond seed,” and is also the German word for the amygdala, the part of the brain most responsible for processing memory and emotion) is at a crossroads. He’s left his doctorate in the German-sounding field of ethnography (we would call him a cultural anthropologist) to write feature pieces for the Arts & Culture section of the Hamburg newspaper. His wife Elisabeth is his editor at the paper, and it’s starting to chafe: “(since I started working for Elisabeth’s department, our marriage has become more professional).” When she sends him on what he considers to be a ridiculous assignment— fly down to Italy’s Lake Lugano to interview Dirk Svensson, a mega-bestselling but reclusive children’s book author, and fly back that night—Daniel knows exactly what she’s punishing him for. She wants a child; Daniel’s resistant.

The specter of that phantom trio (Daniel, Elisabeth, Baby Mandelkern) is only one of a series of threesomes—both romantic and situational— that occur throughout the book, down to Svensson’s three-legged dog. The three-part arithmetic of one person choosing between two options leads to several of the book’s dilemmas, and they’re ones many of us face: I could live here, or there; I could love this woman, or that one; I could have this kind of life, or one completely different. All is not possible; one must choose. When Mandelkern arrives on the shores of Lake Lugano, he’s surprised to find he’s not the only person coming for a visit: a fetching Finnish doctor named Tuuli and her young son also clamber into the boat when Svensson comes to pick them up. And contrary to the dossier given to him by his wife befo

Readers of this blog know that I have, in the last month or so, twice brought Anne Enright's new novel,

The Forgotten Waltz to this virtual page, once to reflect on

Enright's bright capacity with first words and once to

review the book in total. Readers also know what a huge fan I am of

The Gathering, and of writers who write as fiercely and boldly and still beautifully as Enright. Today, and without further ado, I bring you this conversation that Anne Enright graciously agreed to conduct—over email. I asked about that beginning. I asked about criticism and joy. I find her answers to be as astute and smart as her books have always been.

The Forgotten Waltz begins with these words: I met him in my sister’s garden in Enniskerry. That is where I saw him first. There was nothing fated about it, though I add in the summer light and the view. I put him at the bottom of my sister’s garden, in the afternoon, at the moment the day begins to turn. It’s a simple-seeming beginning, but it is not. It is a tempo already firmly established. It is a series of small contradictions, nuance and shadow. Were these the first words that you wrote for this book? Does story take hold of you first, when you are writing, or is something else (the sound of a song, for example) at work?

Every book I write I am asked about beginnings, and I look back at my files and am no closer to an answer. Whatever way I begin, it is not large. I don't sit at the keyboard like a mad pianist about to launch into a Beethoven sonata (neither did Beethoven, for that matter). I pootle along. I rearrange things. I write something small and tuck it away. The 'first words' you read have been written and rewritten many times, as have all the subsequent words in the book. The trick is to keep them fresh. I think I did know what I wanted to write about - I knew a fair amount about Gina and Seán. But, at the beginning of the book, Gina does not know - or not yet. I wanted to catch that sense of 'nearly knowing'. My ideal is a text that that holds a sense of movement and ambiguity. All the fun, for me, comes from finding the right tone. You are interested, you have indicated in previous interviews, not in the absolute good or bad of your characters, but in the arrangement and consequences of their flaws. What have you gained, as a writer, by keeping your eye trained on personal fault lines?

I think it is a more honest way to proceed.

1 Comments on An Interview with Anne Enright, last added: 9/19/2011

Readers will be of different minds about Anne Enright's newest novel,

The Forgotten Waltz (W.W. Norton)

. Those who loved her Booker Prize winning

The Gathering—who couldn't stop dreaming it, thinking it, worrying it—will feel at home inside the sprawling intelligence and dead-on ache of this new book. Those who seek the undergirding of a plotted beginning, middle, and end will perhaps clamor for more undergirding. I happen to fall firmly within the former camp. Anne Enright thrills me. Her audacity does. Her utter, sometimes even wicked command of the interplay between people who are, let's face it, not entirely true to either themselves or to each other. Which means they are just like the rest of us.

Book summaries pain me. I never see that as my job. I limit my responsibilities here to evocations—to letting you know how I

felt when I read, and as I read

The Forgotten Waltz I felt, from the very first, taken in, absorbed, urgent in my need to know, to read more deeply in. I felt alive to Gina Moynihan, Enright's narrator, who is looking back, in a season of snow, on the mystery and ruin of an adulterous affair. The affair hasn't proceeded well; we know this from the start. It has destroyed two marriages, put houses up for sale, and haunted a child who was not altogether well to begin with. Maybe it was all irresistible. Was it? But who is better off in the end?

This a novel that slides back and forth over time and disclosure, through love and accusation, in and out of jobs and hotel rooms, between Ireland and elsewhere. It is a novel that seems to be about one thing then shifts toward another, a novel that doesn't entirely give up the logic of its title. This is a novel, in other words, that doesn't presume the arrogance of a set-aside, easily cataloged or marketed

theme. Enright creates voices. She moves them across the page. They digress, they attack, they submit, they desire, they turn the story on its head, they whisper, they groan. They rail against reason. They want to be reasoned with. And never—never once—do they

concede.Here's Gina speaking:

I feel that the world might be better if it was run by girls who are nearly twelve, the ability they have to be fully moral and fully venal at the same time. Capitalism would certainly thrive.

Here is the passage that I believe explains the workings of this book. The workings, perhaps, of Enright's brilliant and irreducible mind:

When I was twelve or so, I used to practise astral flying—it must have been a fashion then. I lay on my back in bed, and when I was fully heavy, too heavy to move, I got up, in my mind, and left the house. I went down the stairs and out the front door. I walked or I drifted along the street. If I wanted to, I flew. And I imagined, or I saw, every single detail of the passing world; every fact about the hall of the stairs and the street beyond. The next day I would go out to look for things I had noticed, for the first time, the night before. And I found them, too. Or thought I had.

The worst thing about being so caught up in finishing your own book (I am, I think, 5,000 words shy of a complete

Dangerous Neighbors (Egmont USA) prequel) is that when you steal time away for literature (away from your job, away from your duties, away from the laundry), you can't steal enough time for the work of others.

But two days ago, I downloaded my first NetGalley advanced reading copy—

The Forgotten Waltz by the truly brilliant, often disturbing, completely original Anne Enright. I'm only thirty pages in. I'll be doing a full report here (as well as an interview with Ms. Enright, come October). But on this gloriously weathered day, might I just suggest that this, these opening lines, is how books should begin. The voice is true and firm and daring. There is no barrier between writer and reader. Present is past and past is present, and who doesn't want to know what has happened?

i met him in my sister's garden in Enniskerry. That is where I saw him first. There was nothing fated about it, though I add in the late summer light and the view. I put him at the bottom of my sister's garden, in the afternoon, at the moment the day begins to turn. Half five maybe. It is half past five on a Wicklow summer Sunday when I see Sean for the first time. There he is, where the end of my sister's garden becomes uncertain.

You want to know what I like in books? I like this.

By:

Heidi MacDonald,

on 5/29/2011

Blog:

PW -The Beat

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Marvel,

First Second,

Dark Horse,

Disney,

Comic Strips,

Random House,

IDW,

Fantagraphics,

W.W. Norton,

Coming Attractions,

Boom Studios,

Titan Books,

Add a tag

.

Ah… Memorial Day approaches, and with it, summer vacation. Day after day of nothing which must be done, but full of possibilities! Maybe an escape to the air-conditioned refuge of your local library. Perhaps a day spent on the porch, sipping something cold and sinful (I prefer Brown Cows, served in a large ice tea glass). Or maybe hiding away up in a hayloft, or deep in a cool root cellar, where no one can find you. Whatever your preference, there’s nothing like a good book to make you forget the world around you. Below are some suggestions for your summer reading pleasures. (And if you need a nap to avoid the afternoon heat, give your kids something to read. It’ll keep them quiet long enough for you to recharge your batteries.)

The following is a selection of new comics titles due to be published in June 2011. This list is not comprehensive, just what I’ve discovered browsing the Internet. Below, you’ll find selected titles which caught my interest. If you would like to browse forthcoming graphic novels and related books at your leisure, click here. These are not necessarily titles I will purchase, but which I will definitely look at once they arrive at my local comics shop or bookstore.

If you click that link above, you’ll see all the graphic novels at BN.com, sorted by date.

Please be advised that publication dates are not set in stone, titles may change, and covers may be altered. Also, your local comics shop might receive copies before your local neighborhood website or library. I consider my tastes to be rather eclectic. If you feel I’ve neglected or slighted a title, publisher, or creator, please feel free to mention it in the comments below. Yes, you may promote your own work, but please include the ISBN for easy searching (and shopping!)

Disclaimer: I am employed by Barnes & Noble. This and any other posts by me at this site have no official connection to B&N. As always, feel free to send us your PR. Even better, send us some free books!

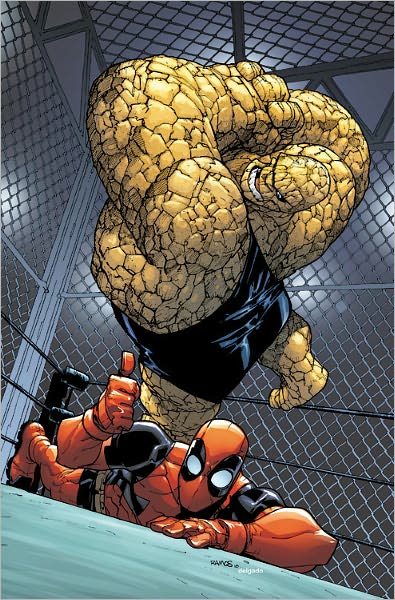

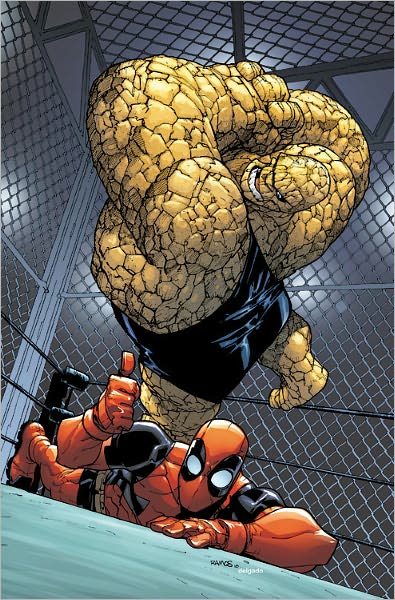

Deadpool Team-Up

by Cullen Bunn, Tom Fowler (Illustrator), Matteo Scalera (Illustrator), Rob Williams

- $ 19.99

- Pub. Date: June 2011

- Publisher: Marvel Enterprises, Inc.

- Format: Hardcover, 168pp

- ISBN-13: 9780785151395

- ISBN: 0785151397

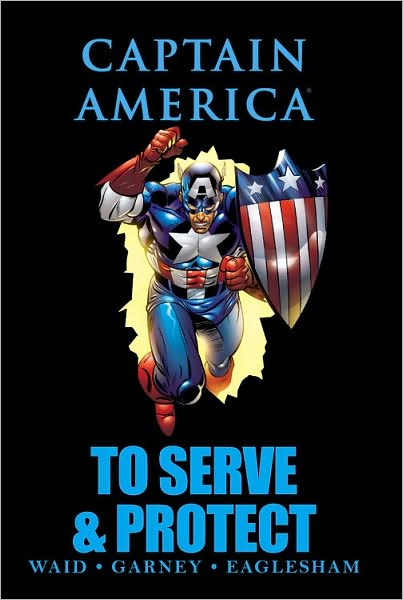

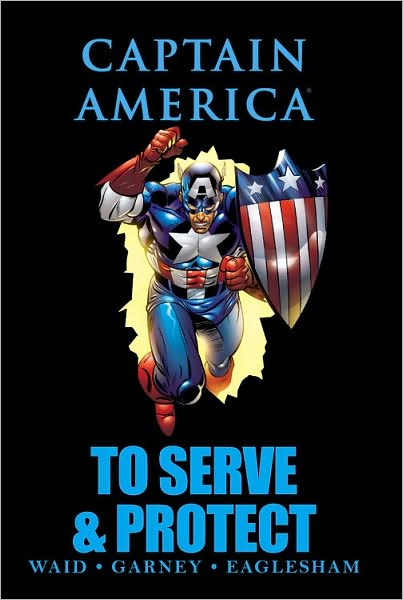

Captain America: To Serve and Protect

by Mark Waid, Ron Garney (Illustrator), Dale Eaglesham (Illustrator)

- $ 24.99

- Pub. Date: June 2011

- Publisher: Marvel Enterprises, Inc.

- Format: Hardcover, 192pp

- ISBN-13: 9780785150824

- ISBN: 078515082X

![]()

This past weekend we took refuge, for a spell, inside the New York Public Library, a place I always try to visit whenever I come to New York.

This past weekend we took refuge, for a spell, inside the New York Public Library, a place I always try to visit whenever I come to New York.

As we stood beneath this Rose Room sky, I recalled, as I always do, my first trip to that building, which happened in the company of my first editor, Alane Salierno Mason. Alane bought three of my books, not just the first, and she brought to each one a rigorous, unyielding eye. Alane cares very much about the state of books, not just in this country, but in the world.

I wrote something about that Rose Room in 1998, in the wake of my experience at the National Book Awards and published it then. Today, in between a spate of client projects, I was feeling melancholy and looked at that old essay again:

Hours before the 49th National Book Awards ceremony got under way, Alane Salierno Mason, my literary editor, remembered a room I had to see; we went. A lion, an edifice, a swoop of stairs, a room: big as a city block, and skied with permanent weather. There were six-hundred pound tables and a constellation of polished lamps, people enough for a subway station, though this was the New York Public Library, the newly splendoured Rose Reading Room. I thought I heard a holy hush. I felt drawn out, thrown out of kilter by the hundreds hunkered down with books.

A while later, John Updike took the stage at the Marriott Marquis to accept the 1998 award for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. His voice had a quiet, avuncular appeal, and in that darkened room he stepped his audience back into the library of his youth, the glamor of a typeface, the beauty of a book “in proportion to the human hand.” There were stacks of books on every table, images of books hung like pendants on the walls. There were authors in the room, editors, publishers, agents, reviewers, there were readers, and we understood why we had come.

The media, the next day and for days to come, would write of dark horses, battlefields, upset victories, dueling styles. They would tally winners and losers as if bookmaking were a gamble or a sport. They would declaim the event because their heroes had not been crowned, because somehow they had not deduced the final outcome. But what too many lost in their rush for the headline was the reality of what that evening was: a celebration of books. A communion of stories. A tribute to the humanity of words.

What I’ll remember is not so much who won, but what was said. What I’ll remember is how Gerald Stern, upon accepting the poetry honor, venerated his fellow poets: individually, distinctively, with elemental and essential grace. I’ll remember how Louis Sachar, winning for Young People’s Literature, did the same, and how Alice McDermott, one of the most exquisite, time-proven novelists in the land, hadn’t the ego to believe her name was called. I’ll remember the dignity of that old-fashioned tribe, the integrity of the jurors, the company I was keeping—my husband, my parents, my brother, the W.W. Norton team, my agent, Amy Rennert. I’ll remember how it felt to be sitting there amongst the others all because I’d been given the certain exceptional privilege of publishing a little book about love.

Why do we read? Why do we write? For me, the answer made itself known some 24 hours prior to the ceremony, when t

I was deeply saddened yesterday to learn, through my agent and friend Amy Rennert, that Carol Houck Smith, the long-time editor at W.W. Norton, had passed away. I met her only once, in 1998, when she escorted Gerald Stern to the National Book Awards, and sat with me and chatted, as if we were lifelong friends. As if I deserved to be there. I emailed with her just occasionally.

I was deeply saddened yesterday to learn, through my agent and friend Amy Rennert, that Carol Houck Smith, the long-time editor at W.W. Norton, had passed away. I met her only once, in 1998, when she escorted Gerald Stern to the National Book Awards, and sat with me and chatted, as if we were lifelong friends. As if I deserved to be there. I emailed with her just occasionally.

But you didn't have to be in her physical presence to feel her emanating goodness, to know that the world was a better place because she lived within it. She edited Andrea Barrett, Rita Dove, Stanley Kunitz, Ron Carlson, Rick Bass, Joan Silber. She was, wrote Andrea Barrett in a statement printed by the Washington Post, the sort of editor who did "the simplest (and hardest) task: she asked questions. Questions that presumed the characters created on the page were actual persons, the actions real and consequential, the meanings a matter of life and death." She was the sort who made you feel welcome at her table, who wrote, once, to say that she had "just finished The House of Mirth, if you can believe that. I needed a respite from this century."

Of the books that she edited, I hold as most special The Wild Braid, that magnificent end-of-life collage by Stanley Kunitz. It was so perfectly odd, so uncontained, a spill of garden, words, living, conversation, photographs, and a nearly final page that seems just rightly quotable, this day, in which so many of us are fondly remembering Carol Houck Smith:

When you look back on a lifetime and think of what has been given to the world by your presence, your fugitive presence, inevitably you think of your art, whatever it may be, as the gift you have made to the world in acknowledgment of the gift you have been given, which is the life itself. And I think the world tends to forget that this is the ultimate significance of the body of work each artist produces. That work is not an expression of the desire for praise or recognition, or prizes, but the deepest manifestation of your gratitude for the gift of life.

The silent auction for the bissell centre will be at City Hall this Friday from 6pm - 10pm. The last pieces are being fired in the kiln (i can't wait to see them!). Hope to see some of you at the auction.

The picture is of my finished piece (not yet fired, so colours will change quite dramatically and it will be glossy). Comes with matching cups (how sweet!)

Renowned comics creator Alan Moore has landed a deal for his second prose novel. Liveright, an imprint at W. W. Norton & Company, will publish Jerusalem in Fall 2016.

Renowned comics creator Alan Moore has landed a deal for his second prose novel. Liveright, an imprint at W. W. Norton & Company, will publish Jerusalem in Fall 2016.

"Critics are like mosquitoes" -- GREAT!