Hike Salary of MLA

Hike Salary of MLA

सावधान .. अगर आप भी किसी विधायक के घर जा रहे हैं तो कृपया करके चाय वाय पी कर जाए अन्यथा … !!!! क्योकि विधायकों का कहना है कि खर्च की तुलना में वेतनमान बेहद कम मिलता है, इसके अलावा महंगाई बहुत ज्यादा है। दिनभर मेल-मुलाकातों के दौरान चाय-पानी पर काफी खर्च आ जाता है। ऐसे में हमें बेहद दिक्कत पेश आती है। हम इमानदारी से काम करने वाले लोग हैं, इसलिए वेतनमान में इजाफा होना चाहिए। सूत्रों का कहना है कि आप सरकार वेतन बढ़ाने की मांग पर कार्रवाई कर सकती है।

‘ ‘ !

नई दिल्लीः घर चलाने के लिए आम आदमी पार्टी (आप) के कई विधायकों ने वेतन बढ़ाए जाने की मांग की है। विधायकों का कहना है कि उनको जो भी वेतनमान मिलता है वह उनके दफ्तर और उससे संबंधित व्यवस्थाओं में ही खर्च हो जाता है, ऐसे में वह अपना घर खर्च कहां से चलाएं। वेतन बढ़ाने के लिए कुछ इसी तरह के तर्क देकर आम आदमी पार्टी के बीस से अधिक विधायकों ने मुख्यमंत्री अरविंद केजरीवाल को पत्र लिखे हैं। इन विधायकों का कहना है कि खर्च की तुलना में वेतनमान बेहद कम मिलता है, इसके अलावा महंगाई बहुत ज्यादा है। दिनभर मेल-मुलाकातों के दौरान चाय-पानी पर काफी खर्च आ जाता है। ऐसे में हमें बेहद दिक्कत पेश आती है। हम इमानदारी से काम करने वाले लोग हैं, इसलिए वेतनमान में इजाफा होना चाहिए। सूत्रों का कहना है कि आप सरकार वेतन बढ़ाने की मांग पर कार्रवाई कर सकती है See more…

AAP MLAs demand a hike in their salaries from Arvind Kejriwal | Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis

A delegation of 20 Aam Aadmi Party legislators on Friday met Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal demanding a hike in their salaries. Taking a clue from Parliamentarians in Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha seeking 100 percent hike in their salaries, the AAP MLAs also decided to approach both Delhi CM and his deputy Manish Sisodia for a similar raise.

While speaking to dna AAP MLA Nitn Tyagi said that a team of 20 legislators had approached the CM, all the legislators unanimously agree that salaries must be raised.

“We get 53,500 in hand and it might sound a lot but we are not able to save a penny for ourselves. In fact I personally have on many occasions used money from my personal savings to work for the people of my constituency,” Tyagi said.

He added that not only him but other MLAs as well end up paying for the office, salaries of helpers, stationeries and so on, and that most of the previously lawmakers would also own business so had not much to rely on government salary.

“This is not the case with us. In a day, dozens of people from my constituency come to meet me with their problems. The people have to be served water, tea or snacks. This is basic courtesy but given the current salary even being courteous is turning out to be expensive for us.” dnaindia.com

तो इसमे गलत ही क्या है अभी नही कर सकते इतना खर्चा इसलिए तो अपने घर के बाहर बोर्ड लगा दिया है jee …

The post Hike Salary of MLA appeared first on Monica Gupta.

By John Knowles

If you become wealthier tomorrow, say through winning the lottery, would you spend more or less working than you do now? Standard economic models predict you would work less. In fact a substantial segment of American society has indeed become wealthier over the last 40 years — married men. The reason is that wives’ earnings now make a much larger contribution to household income than in the past. However married men do not work less now on average than they did in the 1970s. This is intriguing because it suggests there is something important missing in economic explanations of the rise in labor supply of married women over the same period.

One possibility is that what we are seeing here are the aggregate effects of bargaining between spouses. This is plausible because there was a substantial narrowing of the male-female wage gap over the period. The ratio of women’s to men’s average wages; starting from about 0.57 in the 1964-1974 period, rose rapidly to 0.78 in the early 1990s. Even if we smooth out the fluctuations, the graph shows an average ratio of 0.75 in the 1990s, compared to 0.57 in the early 1970s.

The closing of the male-female wage gap suggests a relative improvement in the economic status of non-married women compared to non-married men. According to bargaining models of the household, we should expect to see a better deal for wives—control over a larger share of household resources – because they don’t need marriage as much as they used to. We should see that the share of household wealth spent on the wife increases relative to that spent on the husband.

Bargaining models of household behavior are rare in macroeconomics. Instead, the standard assumption is that households behave as if they were maximizing a fixed utility function. Known as the “unitary” model of the household, a basic implication is that when a good A becomes more expensive relative to another good B, the ratio of A to B that the household consumes should decline. When women’s wages rose relative to men’s, that increased the cost of wives’ leisure relative to that of husbands. The ratio of husbands’ leisure time to that of wives should therefore have increased.

In the bargaining model there is an additional potential effect on leisure: as the share of wealth the household spends on the wife increases, it should spend more on the wife’s leisure. Therefore the ratio of husband’s to wife’s leisure could increase or decrease, depending on the responsiveness of the bargaining solution to changes in the relative status of the spouses as singles.

To measure the change in relative leisure requires data on unpaid work, such as time spent on grocery shopping and chores around the house. The American Time-Use Survey is an important source for 2003 and later, and there also exist precursor surveys that can be used for some earlier years. The main limitation of these surveys is that they sample individuals, not couples, so one cannot measure the leisure ratio of individual households. Instead measurement consists of the average leisure of wives compared to that of husbands. The paper also shows the results of controlling for age and education. Overall, the message is clear; the relative leisure of married couples was essentially the same in 2003 as in 1975, about 1.05.

One can explain the stability of the leisure ratio through bargaining; the wife gets a higher share of the marriage’s resources when her wage increases, and this offsets the rise in the price of her leisure. This raises a set of essentially quantitative questions: Suppose that marital bargaining really did determine labor supply how big are the mistakes one would make in predicting labor supply by using a model without bargaining? To provide answers, I design a mathematical model of marriage and bargaining to resemble as closely as possible the ‘representative agent’ of canonical macro models. I use the model to measure the impact on labor supply of the closing of the gender wage gap, as well as other shocks, such as improvements to home -production technology.

People in the model use their share of household’s resources to buy themselves leisure and private consumption. They also allocate time to unpaid labor at home to produce a public consumption good that both spouses can enjoy together. We can therefore calibrate the model to exactly match the average time-allocation patterns observed in American time-use data. The calibrated model can then be used to compare the effects of the economic shocks in the bargaining and unitary models.

The results show that the rising of women’s wages can generate simultaneously the observed increase in married women’s paid work and the relative stability of that of the husbands. Bargaining is critical however; the unitary model, if calibrated to match the 1970s generates far too much of an increase in the wife’s paid labor, and far too large a decline in that of the men; in both cases, the prediction error is on the order of 2-3 weekly hours, about 10% of per-capita labor supply. In terms of aggregate labor, the error is much smaller because these sex-specific errors largely offset each other.

The bottom line therefore is that if, as is often the case, the research question does not require us to distinguish between the labor of different household or spouse types, then it may be reasonable to ignore bargaining between spouses. However if we need to understand the allocation of time across men and women, then models with bargaining have a lot to contribute.

John Knowles is a professor of economics at the University of Southampton. He was born in the UK and schooled in Canada, Spain and the Bahamas. After completing his PhD at the University of Rochester (NY, USA) in 1998, he taught at the University of Pennsylvania, and returned to the UK in 2008. His current research focuses on using mathematical models to analyze trends in marriage and unmarried birth rates in the US and Europe. He is the author of the paper ‘Why are Married Men Working So Much? An Aggregate Analysis of Intra-Household Bargaining and Labour Supply’, published in The Review of Economics Studies.

The Review of Economic Studies aims to encourage research in theoretical and applied economics, especially by young economists. It is widely recognised as one of the core top-five economics journals, with a reputation for publishing path-breaking papers, and is essential reading for economists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Illustration by Mike Irtl. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Why are married men working so much? appeared first on OUPblog.

An analysis using 120 years of census data

By Sydney Beveridge, Susan Weber and Andrew A. Beveridge, Social Explorer

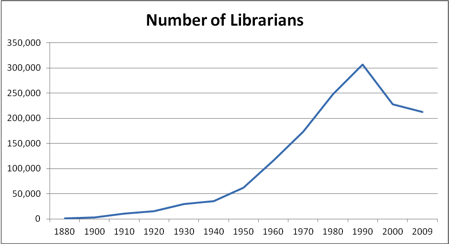

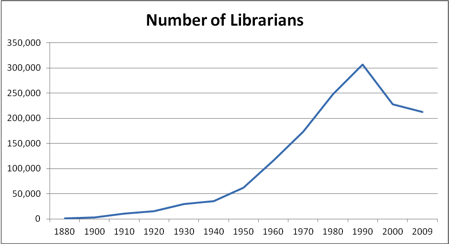

The U.S. Census first collected data on librarians in 1880, a year after the founding of the American Library Association. They only counted 636 librarians nationwide. Indeed, one respondent reported on his census form that he was the “Librarian of Congress.” The U.S. Census, which became organized as a permanent Bureau in 1902, can be used to track the growth of the library profession. The number of librarians grew over the next hundred years, peaking at 307,273 in 1990. Then, the profession began to shrink, and as of 2009, it had dropped by nearly a third to 212,742. The data enable us to measure the growth, the gender split in this profession known to be mostly female, and to explore other divides in income and education, as they changed over time.

We examined a number of socioeconomic trends over the duration, and focused in on 1950 the first year that detailed wage data were recorded, 1990 at the peak of the profession and 2009 the most currently available data.1 We looked at data within the profession and made comparisons across the work world.

For the first 110 years of data, the number of librarians increased, especially after World War II. In 1990, the trend reversed. Over the past 20 years, the number of librarians has dropped by 31 percent, though the decline has slowed.

Considering the nation today, the states with the largest librarian populations are: Pennsylvania, Illinois, New York, Texas and California. Meanwhile, the states with the highest concentrations of librarians (or librarians per capita) are: Vermont, D.C., Rhode Island, Alabama, New Hampshire. Table 1 in the appendix gives the count and proportion of librarians by state in 2009.

Median Earnings

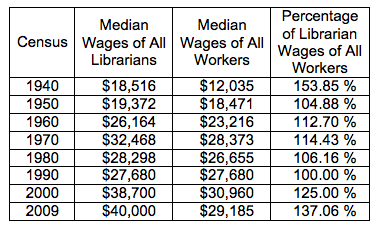

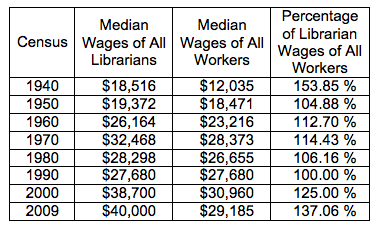

The Census Bureau has kept records of librarian wages since 1940. Median2 Librarian wages (whether full-time or part-time) increased until 1980, though they were a lower percentage of the median wages of all workers. Indeed, between 1970 and 1980 librarian wages declined nearly $4,000—more than twice the drop of median wages across all professions. (This wage drop was in the context of the Oil Embargo in the mid-1970s, and the economic fall-out that that caused.) In 1990 Librarian median wages declined further and were the same as those for all workers, but by 2009 they had gained in relative terms, and reached their peak of $40,000. (All these figures are adjusted for inflation.) By 2009 the typical librarian earned over one-third more than a typical US worker. According to the Census results, Librarians have enjoyed consistently high employment rates. For instance in 2009, the unemployment rate among librarians was just two percent–one-fifth the national rate.

The Census Bureau has kept records of librarian wages since 1940. Median2 Librarian wages (whether full-time or part-time) increased until 1980, though they were a lower percentage of the median wages of all workers. Indeed, between 1970 and 1980 librarian wages declined nearly $4,000—more than twice the drop of median wages across all professions. (This wage drop was in the context of the Oil Embargo in the mid-1970s, and the economic fall-out that that caused.) In 1990 Librarian median wages declined further and were the same as those for all workers, but by 2009 they had gained in relative terms, and reached their peak of $40,000. (All these figures are adjusted for inflation.) By 2009 the typical librarian earned over one-third more than a typical US worker. According to the Census results, Librarians have enjoyed consistently high employment rates. For instance in 2009, the unemployment rate among librarians was just two percent–one-fifth the national rate.

A Feminine Profession

Today, 83 percent of librarians are women, but in the 1880s men had the edge, making up 52 percent of the 636 librarians enumerated. In 1930, male librarians were truly rare, making up just 8 percent of the librarian population.

By Mariko Lin Chang

Last week, the Senate Republicans defeated the Paycheck Fairness Act. The bill would have strengthened the Equal Pay Act by providing more effective protections and remedies to victims of sex discrimination in wages, including prohibiting employers from retaliating against employees who discuss their wages with another employee, requiring employers to prove that wage differences between women and men doing the same work are the result of education, training, experience, or other job-related factors, and providing victims of sex discrimination in wages the same legal remedies currently available to those experiencing pay discrimination on the basis of race or national origin.

Was the bill perfect? Probably not (few, if any bills could be considered perfect). But the Republican senators threw the baby out with the bath water.

I think most members of the Senate believe that women should be paid the same amount as men for doing the same job. Yet many did not support the Paycheck Fairness Act. Perhaps their reluctance had to do with partisan politics or opponents’ arguments that it would be bad for business. Regardless of their reasons for not supporting the bill, if bill had been about pay discrimination on the basis of race, I think it would have passed long ago because the political fall-out for failing to oppose racial discrimination is much steeper than failing to oppose sex discrimination.

Why is it OK to continue to allow pay discrimination against women? Why do we accept this as a fact of life? And why should victims of sex discrimination in wages be denied the same legal remedies as victims of racial discrimination?

Issues pertaining to sex discrimination have been relegated to the second-class status of “women’s issues.” And because “women’s issues” have become imbued with divisive issues such as abortion, it has become more politically and socially acceptable to oppose legislation promoting the rights of women–even if it’s the right to equal pay.

Another reason the Paycheck Fairness Act experienced push-back is that many believe pay inequities are a result of women choosing jobs that are more compatible with family responsibilities or of women having less job experience because of years out of the labor force. But the Act did not state that women and men should receive the same pay regardless of work experience, occupation, or level of education. The Act acknowledged that pay differences based on these factors are not discrimination.

The Paycheck Fairness Act was about women receiving the same pay as men for doing the same work. It’s time we hold our Congressional representatives to the national principle that everyone (regardless of gender, race, national origin, or religion) deserves equal pay for equal work.

Mariko Lin Chang, PhD, is a former Associate Professor of Sociology at Harvard University. She currently works with universities to diversify their faculty and also works as an independent consultant specializing in data analysis of wealth inequality in the US. Chang is the author of Shortchanged: Why Women Have Less Wealth and What Can Be Done About It.