new posts in all blogs

Viewing Blog: Books of Wonder and Wisdom, Most Recent at Top

Results 1 - 25 of 234

Multicultural read-alouds that foster peace, justice, respect and curiosity

Statistics for Books of Wonder and Wisdom

Number of Readers that added this blog to their MyJacketFlap: 1

How to spot beauty in all its motley habitats is the rare insight offered by a wise, patient grandmother in Matt de la Peña’s life-affirming picture book Last Stop on Market Street.

Young CJ and his grandmother leave their city church with its bright stained-glass windows to board a bus across town. As they travel, the child, feeling a bit irritable, peppers his grandmother with typically puerile complaints.

The boy objects to the rain, then to the lack of a family car, and even to this Sunday excursion with his grandmother. Yet each time he perceives something negative, Nana calls his attention to the positive aspects he’s overlooked. Rain? “Trees get thirsty, too,” she points out. And instead of a car, the two of them get to ride in “a bus that breathes fire,” with a driver who shares magic tricks.

The trip itself takes on deeper meaning, especially as portrayed by Christian Robinson’s bright, naïf images created with acrylics, collage, and digital enhancements. Along with CJ, readers will encounter an intriguing array of riders, ranging from a peach-colored guitarist, a gray-haired woman holding a jar filled with butterflies, the smiling caramel-toned conductor, the pale bald-headed fellow with green tatooes, and the sad-eyed businessman.

CJ has not lost his tetchiness yet, though. When a blind man boards the bus with his dog, the boy asks, “How come that man can’t see?”. The grandmother’s simple response is rich with symbolic beauty: “Boy, what do you know about seeing?”

Tellingly, the grandmother is not the only one with valuable insight to share with the child. The blind man and then the guitarist inspire the child to experience the world with sensitivity and exuberance.

As CJ and Nana reach their destination, readers finally discover it’s a soup kitchen. We have accompanied this pair from one side of town to the other, traversing different socioeconomic neighborhoods and arriving at a fuller appreciation of both humanity’s needs and its wondrous diversity. It’s been a magical journey.

Reprinted with permission from New York Journal of Books.

See also …

Filed under:

Peace stories,

Picture Books Tagged:

Christian Robinson,

empathy,

Matt de la Peña,

multicultural literature,

respect

The stirring stories of two courageous children from Pakistan arise from the colorful pages of Jeanette Winter’s latest picture-book biography.

Known for her award-winning children’s books featuring activists working for peace and justice, Winter (Nasreen’s Secret School, 2009), turns her clear eye to the valiant efforts of two who spoke out against a society that deprived young people of their right to an education (Malala Yousafzai) or the right to protection from exploitation (Iqbal Masih). Since the children faced violent consequences – Malala was shot, while Iqbal was murdered – the author/illustrator took an unusual risk with this book intended for a young audience.

As with her other works, Winter offers spare text, simple illustrations, and a hopeful tone. For Malala, a Brave Girl from Pakistan/Iqbal, a Brave Boy from Pakistan, she adds a pleasingly creative format: The reader can choose one story and then flip the book over to read the other. She introduces each child with a one-page note providing the essential context for his or her story, and follows that with the same quote from Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengali writer and educator who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913: “Let us not pray to be sheltered from dangers, but to be fearless when facing them.”

Malala’s account will be more familiar to readers. Despite the Taliban’s efforts to prevent girls from attending school, Malala and her classmates rebel and keep going. To reduce their risks, the girls begin to travel to and from school in a van, but even then they are not safe. One day, a Taliban fighter stops the van and asks, “Who is Malala? Speak up, otherwise I will shoot you all.” In the author’s note, we learn the bullet went through Malala’s head and neck to her shoulder.

After the van takes her to the local hospital, she is transferred to other sites, where doctors succeed in saving her life. On her 16th birthday, Malala, nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2013, tells an audience of world leaders: “They thought that bullets would silence us, but they failed …. One child, one teacher, one book, one pen, can change the world.”

Between the two stories lies a center spread showing each child on opposite sides, with a kite, symbolic of freedom, soaring toward the other. With eloquent symmetry, Malala, dressed in her pink and coral shalwar kameez, stands on a gray mountain peak and holds onto her kite, while Iqbal, depicted in a ghostly shade of gray, stands on a pink and coral peak and releases his kite. In the background, a golden crescent moon and rounded stars shine in a dusky purple sky.

Iqbal, we learn, loses his freedom at the age of 4, when his destitute parents borrow $12 from a carpet factory owner. The gruff owner tells the bewildered boy, shown holding a coral and purple kite, “No kites here!” and then drags him inside the dark factory and chains the child to a loom.

Trudging home one night, 10-year-old Iqbal sees a notice announcing a meeting about Peshgi, the loans that hold children in bondage. There, he learns that Peshgi has been outlawed and all loans forgiven. He rushes to the factory and shouts, “You are free! We are free!”

Not only does Iqbal head to school, he keeps spreading the news of freedom to other bonded children. Two years later, a bullet ends the brave boy’s life.

Showing an astute awareness that the story of Iqbal’s brief life might well have dismayed young readers, Ms. Winter has wisely paired it with the more uplifting one of Malala. In doing so, she provides adults with an exceptional opportunity to discuss with children the value of following one’s conscience and the need to stand up for justice, freedom and equality.

Reprinted with permission from the New York Journal of Books.

And see my prior posts on Winter’s other well-crafted books, such as Kali’s Song and Henri’s Scissors.

Filed under:

Biographies/Autobiographies,

Hero stories,

Peace stories,

Picture Books Tagged:

Iqbal Masih,

Jeanette Winter,

Malala Yousafzai,

social justice

Sometimes a quiet story can achieve feats that rousing tales can’t. The Olive Tree, a simple yet subtle story set in contemporary Lebanon, offers no details or explanation of the 1975 Lebanese Civil War, but invites us to consider the lingering distrust among people and possible paths to reconciliation.

We learn from young Sameer how the house next door was empty for years. “The family who lived there had gone away during the troubles, because they were different from most of the people in the village. But now, thank goodness, the long war was over, and they were coming back.”

Beneath the ample branches of the old olive tree that grows on the other side of the wall, Sameer observes the neighbors as they return home. He notices the family has a girl named Muna, who was about his age. Sadly, neither she nor her family members show any inclination to become friends.

In time, the olives begin to ripen, and Sameer, as he does every year, sets out to gather those that have fallen in his yard. After all, they’re “the best olives in Lebanon,” his mother says. But one morning Muna sees him with a basket full of olives and complains: “Those are our olives, you know. Ours!”

Taken aback, Sameer points out that all the years they were away, Sameer and his family took care of the tree. “We have a right to the olives,” he says.

Muna insists that now that they’re back, they’ll take care of the tree and have all the olives. In his anger, Sameer leans over the wall and dumps his basket of olives into her yard.

Then one night a mighty storm descends and lightning strikes the tree, leaving a shattered stump and a broken stone wall. The children, confronting the loss of the precious old tree, discover they can put aside their differences and begin to live in harmony with each other and the land.

Ms. Ewart’s atmospheric, two-page spreads of naturalistic watercolor paintings flesh out the poignant story with realistic details. The mothers of both families wear the hijab; a goat, a donkey, and chickens populate the yards; and chairs have seats of woven bulrush.

With Elsa Marston’s understated story of conflict resolution, The Olive Tree offers adults a valuable opportunity to discuss with children the importance of respect for all.

Reprinted with permission of The New York Journal of Books.

See also …

Filed under:

Friendship,

Peace stories,

Picture Books Tagged:

Claire Ewart,

Elsa Marston,

Middle East

Winter’s splendors shine in the latest collaboration between award-winning children’s poet Joyce Sidman and illustrator Rick Allen, whose stellar prints graced the author’s Newbery Honor-winning poetry collection Dark Emperor and Other Poems of the Night (2010).

As with their previous work, Winter Bees and Other Poems of the Cold hums with a glorious trio of lyrical poetry, vibrant artwork, and natural science explained in crisp prose. The dozen brief poems show off a range of voices, tones, and formats in a full-throated effort to move readers to appreciate how the natural world adapts to the cold.

Employing a clear, consistent format of vivid double-page spreads showcasing the poem on the left and scientific information on the right, the poet and illustrator work harmoniously to stunning effect. Opening with the graceful “Dream of the Tundra Swan,” the team then moves on to feature coiled snakes, a new snowflake that “leaps, laughing/ in a dizzy cloud,/a pinwheel gathering glitter,” a rascally moose, winter bees, and others.

Ms. Sidman performs a sprightly dance with each of her subjects, dipping into rich sensory details with élan and displaying her facility with rhyme, rhythm, and poetic devices. She writes some poems from the perspective of a particular animal (“Brother Raven, Sister Wolf”) and throughout, shows a remarkable talent in her choice of poetic form. For “Under Ice,” Ms. Sidman writes of beavers in the form of a pantoum, distinguished by a pattern of using the poem’s second and fourth lines as the first and third of the next stanza. The last stanza employs the first and third lines in reverse order; thus, the poem’s final line is the same as the first. In this way the poet comes full circle, opening and closing with the image of the beavers’ snug winter home, “the fat white wigwam.”

These fresh poems spring to life with Mr. Allen’s original linoleum block prints, hand-colored and digitally scanned, composed and layered. The snowy images on these pages quiver with movement and assorted perspectives. As readers note the tundra swan’s upcoming “yodel of flight,/the sun’s pale wafer,/the crisp drink of clouds,” they can trace the V formations the vigorous swans make as they soar above a frosty lake. On subsequent pages, we see a chickadee preening, springtails flipping, a wolf prowling, and a ravenous moose reaching for a slender tree branch. The artist’s pleasing range of perspectives— from the upward view of tall trees and frigid sky to the downward gaze at a small fox coiled for warmth– can’t help but engage the reader. The illustrator offers fascinating glimpses of such internal worlds as the beavers’ cramped rooms beneath an icy pond and the winter bees clustered around their queen.

Winter Bees will make for a lovely companion on a chilly night, accompanied by hot cocoa and snuggles with young ones. Even middle-schoolers won’t be able to resist this bright concoction of art, words, and science. The glossary at the end serves to clear up any confusion about scientific terms and poem forms related to the text.

Reprinted with permission from New York Journal of Books.

See also …

Filed under:

Animals,

Nonfiction,

Picture Books,

Poetry,

Winter stories Tagged:

Joyce Sidman,

Rick Allen

Once again mining her memories, Patricia Polacco presents a tender story of how she came to trust in her own abilities. As in previous picture books (Thank You, Mr. Falker and Junkyard Wonders), it’s a caring teacher who helps the young protagonist on her way to self-confidence.

In Mr. Wayne’s Masterpiece, Trisha tells us how terrified she is to stand up and speak before an audience. In the opening scene, her teacher, Mr. T., gently encourages her to read her essay to the class. After some painfully silent moments, he relents and lets her return to her seat. Polacco’s full-page pencil-and-marker image of the wide-eyed, frightened girl reveals her inner turmoil and irrational fear.

Luckily, that teacher doesn’t give up; instead, he chooses a roundabout way to help Trisha get past her anxiety by getting her to help the drama teacher, Mr. Wayne, prepare for the upcoming winter play. At first, she helps paint the scenery flats for Musette in the Snow Garden, jokingly referred to by its author –Mr. Wayne– as a masterpiece. As Trish spends more and more time building the sets, she hears the cast rehearse and learns the words to all the parts.

Soon, whenever an actor forgets or fumbles a line, Trisha becomes the prompter. She likes that role, especially since she doesn’t have to get out on the stage.

But when the girl playing the main character suddenly moves away, Trisha is confronted with a fearful choice: Does she replace the actor or let the play fall apart? Trisha finds she’s not really alone. Mr. Wayne works with her individually, praising her good memory and giving her pointers on breathing and moving. “Patricia, let the play take you.”

And that’s just what she does. Many older-elementary children, especially those experiencing stage fright or shyness, will relate to this joyous story with its triumphant protagonist. Teachers preparing to introduce a play will want to read this aloud in a group setting, and parents should pick this up if they want to reassure a child who’s afraid of performing before a crowd. And as usual, you can rely on Polacco to show classrooms resonant with personality and ethnic diversity.

See also …

my previous post on The Blessing Cup, as well as the post on Junkyard Wonders and other anti-bullying books. And consider these books by Patricia Polacco:

Filed under:

Peace stories,

Picture Books Tagged:

Patricia Polacco,

self-esteem

Do bookstores have to be so predictable in their Halloween displays, as yet again they promote ho-hum Clifford and Curious George and Scooby-Doo products? Families can save their money and their sanity by heading to the library instead, where an array of craft books, poetry, folktales, and novels await anyone with a library card.

One way to combat the oppressive commercialism that has crept into the holiday is to make it yo urself — whether it’s costumes, decorations, puppets, or cupcakes. Look for craft books by Kathy Ross, such as All New Crafts for Halloween. And remember feeling proud of those monsters you drew with the help of the wonderful old Ed Emberley’s Halloween Drawing Book? Don’t let your children grow up without Emberley’s engrossing little books. An alternative for slightly older children is Ralph Masiello’s Halloween Drawing Book.

urself — whether it’s costumes, decorations, puppets, or cupcakes. Look for craft books by Kathy Ross, such as All New Crafts for Halloween. And remember feeling proud of those monsters you drew with the help of the wonderful old Ed Emberley’s Halloween Drawing Book? Don’t let your children grow up without Emberley’s engrossing little books. An alternative for slightly older children is Ralph Masiello’s Halloween Drawing Book.

Ghosts, ghouls and humor show up in plenty of kid-pleasing poetry.  Adam Rex’s Frankenstein Makes a Sandwich and his follow-up, Frankenstein Takes the Cake will have children (and parents?) howling with laughter. The illustrations are as much fun as the punchy poems featuring various monsters.

Adam Rex’s Frankenstein Makes a Sandwich and his follow-up, Frankenstein Takes the Cake will have children (and parents?) howling with laughter. The illustrations are as much fun as the punchy poems featuring various monsters.

Other titles to look for are compilations such as Jack Prelutsky’s It’s Halloween, Lee Bennett Hopkins’ Halloween Howls: Holiday Poetry or Marc Brown’s Scared Silly: A Halloween Book for the Brave: Poems, Riddles, Jokes, Stories and More.

For some of the best seasonal stories, head over to 398.2 for folk literature from around the world. One of  the most dog-eared, beloved collections in my school library was Short & Shivery: Thirty Chilling Tales retold by Robert D. San Souci. Ranging from diverse cultures, the stories are not uniformly scary, but they are all well-written and accessible to children ages 8 to 12. The volume includes such memorable tales as the Appalachian “Tailypo,” the Grimm Brothers’ “Robber Bridegroom,” and “Skeleton’s Dance,” from Japan. Audio- and e-book editions are also available. Another winner is any of the perpetually popular Alvin Schwartz collections, such as Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, illustrated ghoulishly by Stephen Gammell.

the most dog-eared, beloved collections in my school library was Short & Shivery: Thirty Chilling Tales retold by Robert D. San Souci. Ranging from diverse cultures, the stories are not uniformly scary, but they are all well-written and accessible to children ages 8 to 12. The volume includes such memorable tales as the Appalachian “Tailypo,” the Grimm Brothers’ “Robber Bridegroom,” and “Skeleton’s Dance,” from Japan. Audio- and e-book editions are also available. Another winner is any of the perpetually popular Alvin Schwartz collections, such as Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, illustrated ghoulishly by Stephen Gammell.

The stra nge Scottish legend of Tam Lin has been around for centuries, and Jane Yolen’s beautiful, lyrical writing does justice to the thrilling tale of of a brave young woman who rescues a man kidnapped by the Queen of the Fairies. Even young adults would enjoy this powerful love story set on All Hallows Eve.

nge Scottish legend of Tam Lin has been around for centuries, and Jane Yolen’s beautiful, lyrical writing does justice to the thrilling tale of of a brave young woman who rescues a man kidnapped by the Queen of the Fairies. Even young adults would enjoy this powerful love story set on All Hallows Eve.

As for novels, many older children (ages 10+) will be drawn to Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book, winner of the 2009 Newbery Medal, which unspools the bizarre adventures of a boy called Bod as he grows up being raised by ghosts in a cemetery. Gaiman reads his gripping novel aloud on his well-crafted web site.

For slightly younger ones (ages 8 to 12), it’s hard to top James Howe’s Bunnicula series, featuring an evil-looking bunny (found at a Dracula movie) that comes to live with the Monroes, Harold the dog and Chester the cat. When various vegetables show up with teeth marks and drained of all juice and color, the clever cat ascertains the toothy truth. Who knew a vampire story could be so much fun? Another witty one (for ages 6 to 8) is Kate DiCamillo’s Princess in Disguise, in which the pig Mercy Watson is persuaded to dress up in a pink gown and tiara.

And for younger ones:

See my prior post on Julia Donaldson’s Room on the Broom, as well as any of the tales featured in the 2011 Scholastic DVD Teeny-Tiny Witch Woman and More Spooky Halloween Stories.

Filed under:

Art,

Autumn Read-alouds,

Folk and Fairy Tales,

Holidays,

Poetry Tagged:

Halloween

By:

Janice Floyd Durante,

on 10/2/2014

Blog:

Books of Wonder and Wisdom

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Creativity,

Picture Books,

Self-confidence,

Andrea Beaty,

Perseverance,

David Roberts,

curiosity,

Women's history,

Gender equity,

Add a tag

What are the chances that a picture book told in rhyme would succeed in revealing the seldom-featured value of apparent failure and the need for perseverance? Not only that, the author and illustrator would show how females can overcome inner doubts and cultural biases by pursuing their own ideas. The unlikely and totally likable Rosie Revere, Engineer celebrates girl power in a big way.

The can-do spirit of this story, which echoes Peggy Seeger’s acerbic “I’m Gonna Be An Engineer” (1970), in which Seeger advocated for pay parity, respect, and equal opportunities for women, employs humor, rhyme, and bright, detailed watercolor, pencil, and pen-and-ink illustrations to reach impressionable children in need of positive themes.

Wide-eyed Rosie, shown with hair tucked into a red polka-dot kerchief, is a tinkerer at heart. She routinely scrounges in waste baskets for treasures she can use to build things in her room at night. David Roberts provides delightful two-page spreads highlighting the child’s various designs, tools, and original gadgets. These illustrations alone will have children poring over this picture book again and again.

While Rosie beams when her inventions such as helium pants (!) are a hit, she becomes discouraged after her zookeeper uncle laughs at the snake-repelling hat she created for him. “She stuck the cheese hat on the back of her shelf/ and after that day kept her designs to herself.”

What Rosie needs is a mentor, and fortunately, her great-great-aunt Rose, “who’d worked building airplanes a long time ago,” is a dynamo. When again Rosie’s inventions don’t work according to plan, her relative urges her on, stressing that “failed” attempts provide opportunities for learning and, in time, for succeeding.

Rosie regains her groove and goes on to inspire her classmates, who ultimately join in working, learning, and creating the gizmos of their dreams.

Adding value to the exuberant plot are author’s notes about the actual Rosie the Riveter and facts about women’s contributions to aeronautics. Don’t miss reading this book aloud to a group, or revelling in its encouraging message with your young ones, especially girls. Required reading for ages 5 to 9.

And check out these related posts, on Mordecai Gerstein’s The First Drawing, and on architects and builders.

Filed under:

Picture Books,

Women's history Tagged:

Andrea Beaty,

Creativity,

curiosity,

David Roberts,

Gender equity,

Perseverance,

Self-confidence

What are the chances that a picture book told in rhyme would succeed in revealing the seldom-featured value of apparent failure and the need for perseverance? Not only that, the author and illustrator would show how females can overcome inner doubts and cultural biases by pursuing their own ideas. The unlikely and totally likable Rosie Revere, Engineer celebrates girl power in a big way.

The can-do spirit of this story, which echoes Peggy Seeger’s acerbic “I’m Gonna Be An Engineer” (1970), in which Seeger advocated for pay parity, respect, and equal opportunities for women, employs humor, rhyme, and bright, detailed watercolor, pencil, and pen-and-ink illustrations to reach impressionable children in need of positive themes.

Wide-eyed Rosie, shown with hair tucked into a red polka-dot kerchief, is a tinkerer at heart. She routinely scrounges in waste baskets for treasures she can use to build things in her room at night. David Roberts provides delightful two-page spreads highlighting the child’s various designs, tools, and original gadgets. These illustrations alone will have children poring over this picture book again and again.

While Rosie beams when her inventions such as helium pants (!) are a hit, she becomes discouraged after her zookeeper uncle laughs at the snake-repelling hat she created for him. “She stuck the cheese hat on the back of her shelf/ and after that day kept her designs to herself.”

What Rosie needs is a mentor, and fortunately, her great-great-aunt Rose, “who’d worked building airplanes a long time ago,” is a dynamo. When again Rosie’s inventions don’t work according to plan, her relative urges her on, stressing that “failed” attempts provide opportunities for learning and, in time, for succeeding.

Rosie regains her groove and goes on to inspire her classmates, who ultimately join in working, learning, and creating the gizmos of their dreams.

Adding value to the exuberant plot are Beaty’s notes about the women who entered the workforce during World War II and facts about women’s contributions to aeronautics. Don’t miss reading this book aloud to a group, or revelling in its encouraging message with your young ones, especially girls. Required reading for ages 5 to 9.

And check out these related posts, on Mordecai Gerstein’s The First Drawing, and on architects and builders.

Filed under:

Picture Books,

Women's history Tagged:

Andrea Beaty,

Creativity,

curiosity,

David Roberts,

Gender equity,

Perseverance,

Self-confidence

In yet another celebration of creativity, acclaimed author/illustrator Ashley Bryan shares with readers his “family of hand puppets,” crafted with far-flung detritus. Peach pits become eyes … a coconut morphs into a head … a wishbone evokes whiskers. Oh, the random scraps that unfurl a panorama of puppets fit for the wildest tales!

Ashley Bryan’s Puppets is not a craft book; rather, it’s an unusual poetry collection utilizing vibrant photos and a simple poem Bryan wrote for each of the 33 puppets showcased here. Clearly an act of love and joy, Bryan has bestowed every puppet with personality and a relevant name. Lubangi, meaning born in water, is a mermaid draped in netting studded with starfish and cockle shells. Jojo, the storyteller, has a head and hands made of gloves: “In every finger of my glove/ I tap tall tales of peace and love./ The fingers of my well-gloved hands/ Store stories told in foreign lands.”

In his note, the author/creator relates that as he walks the shores of his longtime home in the Cranberry Isles of Maine, he collects shells, bone, driftwood, nets, and sea glass. What child wouldn’t relate to this impulse? While readers won’t find instructions or photos of the author’s creative process (alas), they will find plenty of inspiration for their own puppets. Parents and young ones can use this book as a source for ideas, while teachers and librarians might select a few poems and photos to share as part of a puppet-making project based on folktales — perhaps using one of Bryan’s own vivid versions.

And see my prior post on the acclaimed author/illustrator Ashley Bryan.

Filed under:

Animals,

Art,

Nonfiction,

Picture Books,

Poetry

In yet another celebration of creativity, acclaimed author/illustrator Ashley Bryan shares with readers his “family of hand puppets,” crafted with far-flung detritus. Peach pits become eyes … a coconut morphs into a head … a wishbone evokes whiskers. Oh, the random scraps that unfurl a panorama of puppets fit for the wildest tales!

Ashley Bryan’s Puppets is not a craft book; rather, it’s an unusual poetry collection utilizing vibrant photos and a simple poem Bryan wrote for each of the 33 puppets showcased here. Clearly an act of love and joy, Bryan has bestowed every puppet with personality and a relevant name. Lubangi, meaning born in water, is a mermaid draped in netting studded with starfish and cockle shells. Jojo, the storyteller, has a head and hands made of gloves: “In every finger of my glove/ I tap tall tales of peace and love./ The fingers of my well-gloved hands/ Store stories told in foreign lands.”

In his note, the author/creator relates that as he walks the shores of his longtime home in the Cranberry Isles of Maine, he collects shells, bone, driftwood, nets, and sea glass. What child wouldn’t relate to this impulse? While readers won’t find instructions or photos of the author’s creative process (alas), they will find plenty of inspiration for their own puppets. Parents and young ones can use this book as a source for ideas, while teachers and librarians might select a few poems and photos to share as part of a puppet-making project based on folktales — perhaps using one of Bryan’s own vivid versions.

And see my prior post on Ashley Bryan.

Filed under:

Animals,

Art,

Nonfiction,

Picture Books,

Poetry

Parrots Over Puerto Rico, winner of the 2014 Robert F. Sibert Medal, plunges readers into verdant forests where bright blue Puerto Rican parrots fluttered in ancient canopies for eons. This nonfiction picture book deftly tells the intertwined stories of the island’s history and of the birds’ near-extinction and subsequent recovery.

Parrots Over Puerto Rico, winner of the 2014 Robert F. Sibert Medal, plunges readers into verdant forests where bright blue Puerto Rican parrots fluttered in ancient canopies for eons. This nonfiction picture book deftly tells the intertwined stories of the island’s history and of the birds’ near-extinction and subsequent recovery.

Known for her colorful collages, Susan Roth proves herself up to the challenge of creating vibrant, personality-filled images of the raucous flocks that once thronged the island that came to be called Puerto Rico. Using a pleasing range of textured paper and fabric and employing a vertical (rather than horizontal) layout, Roth depicts the lush natural environment filled with sierra palm trees, tiny tree frogs and crops of corn, yucca, and sweet potatoes.

Co-written with Cindy Trumbore, the book reveals the evolution of the island’s peoples and environment. The Tainos, who arrived around 800 CE, gave the parrots the name iguaca, echoing their harsh calls. In time, the Spanish came, as well as slaves brought from Africa. Predators such as black rats, thrashers, and swarms of honeybees invaded and attacked the parrots. By 1967, many forests had disappeared, and only 24 parrots lived in Puerto Rico.

Only a concerted effort by scientists, environmentalists, public officials, and citizens could save and protect the parrots. Scientists — and parrots — had to battle hurricanes, thunderstorms, wrecked buildings and trees. Thanks to decades of dedicated work, the parrots are still flying over their native isle.

Because of its somewhat detailed and abundant text, Parrots Over Puerto Rico lends itself best to one-on-one sharing or to independent reading by young nature lovers ages 8 to 10.

For more fine nonfiction picture books, see …

Filed under:

Animals,

Nonfiction,

Picture Books Tagged:

Cindy Trumbore,

Endangered species,

Natural history,

Puerto Rico,

Susan L. Roth

Parrots Over Puerto Rico, winner of the 2014 Robert F. Sibert Medal, plunges readers into verdant forests where bright blue Puerto Rican parrots fluttered in ancient canopies for eons. This nonfiction picture book deftly tells the intertwined stories of the island’s history and of the birds’ near-extinction and subsequent recovery.

Parrots Over Puerto Rico, winner of the 2014 Robert F. Sibert Medal, plunges readers into verdant forests where bright blue Puerto Rican parrots fluttered in ancient canopies for eons. This nonfiction picture book deftly tells the intertwined stories of the island’s history and of the birds’ near-extinction and subsequent recovery.

Known for her colorful collages, Susan Roth proves herself up to the challenge of creating vibrant, personality-filled images of the raucous flocks that once thronged the island that came to be called Puerto Rico. Using a pleasing range of textured paper and fabric and employing a vertical (rather than horizontal) layout, Roth depicts the lush natural environment filled with sierra palm trees, tiny tree frogs and crops of corn, yucca, and sweet potatoes.

Co-written with Cindy Trumbore, the book reveals the evolution of the island’s peoples and environment. The Tainos, who arrived around 800 CE, gave the parrots the name iguaca, echoing their harsh calls. In time, the Spanish came, as well as slaves brought from Africa. Predators such as black rats, thrashers, and swarms of honeybees invaded and attacked the parrots. By 1967, many forests had disappeared, and only 24 parrots lived in Puerto Rico.

Only a concerted effort by scientists, environmentalists, public officials, and citizens could save and protect the parrots. Scientists — and parrots — had to battle hurricanes, thunderstorms, wrecked buildings and trees. Thanks to decades of dedicated work, the parrots are still flying over their native isle.

Because of its somewhat detailed and abundant text, Parrots Over Puerto Rico lends itself best to one-on-one sharing or to independent reading by young nature lovers ages 8 to 10.

For more fine nonfiction picture books, see …

Filed under:

Animals,

Nonfiction,

Picture Books Tagged:

Cindy Trumbore,

Endangered species,

Natural history,

Puerto Rico,

Susan L. Roth

Summertime, and creativity is easy. Are you and your children looking for inspiration for art projects? Just dip into acclaimed author/illustrator Lois Ehlert’s latest, The Scraps Book: Notes from a Colorful Life, and you might not even finish the book until you’ll be itching to go for a nature walk to scavenge materials for little masterpieces.

a Colorful Life, and you might not even finish the book until you’ll be itching to go for a nature walk to scavenge materials for little masterpieces.

Known for her bright collages, Ehlert has written and, of course, illustrated a brief, lively memoir that touches upon her early influences, her artistic process, and her many children’s books. She shows photographs of herself and her parents, whom she credits as being people “who made things with their hands.” She includes images of old scissors, paintbrushes, pumpkin seeds and crab apples, even the folding table her dad set up for her as a child and which she took with her to art school years later. We get to feast on colorful images from her popular titles such as Planting a Rainbow, Nuts to You! and Chicka Chicka Boom Boom. In the process of revealing all this, she provides engaging and accessible ideas for young artists’ own work: a paper aquarium … a cat mask … a flower necklace.

Because of Ehlert’s vivid illustrations and her exuberant focus on the creative process, The Scraps Book promises to appeal to a wide range of children, from 5 to 10. I join the artist in wishing you a colorful life.

Ehlert’s other picture books are aimed at ages 5 to 8; recommended titles include …

Filed under:

Biographies/Autobiographies,

Nonfiction,

Picture Books,

Women's history Tagged:

Creativity,

curiosity,

Lois Ehlert

Summertime, and creativity is easy. Are you and your children looking for inspiration for art projects? Just dip into acclaimed author/illustrator Lois Ehlert’s latest, The Scraps Book: Notes from a Colorful Life, and you might not even finish the book until you’ll be itching to go for a nature walk to scavenge materials for little masterpieces.

a Colorful Life, and you might not even finish the book until you’ll be itching to go for a nature walk to scavenge materials for little masterpieces.

Known for her bright collages, Ehlert has written and, of course, illustrated a brief, lively memoir that touches upon her early influences, her artistic process, and her many children’s books. She shows photographs of herself and her parents, whom she credits as being people “who made things with their hands.” She includes images of old scissors, paintbrushes, pumpkin seeds and crab apples, even the folding table her dad set up for her as a child and which she took with her to art school years later. We get to feast on colorful images from her popular titles such as Planting a Rainbow, Nuts to You! and Chicka Chicka Boom Boom. In the process of revealing all this, she provides engaging and accessible ideas for young artists’ own work: a paper aquarium … a cat mask … a flower necklace.

Because of Ehlert’s vivid illustrations and her exuberant focus on the creative process, The Scraps Book promises to appeal to a wide range of children, from 5 to 10. I join the artist in wishing you a colorful life.

Ehlert’s other picture books are aimed at ages 5 to 8; recommended titles include …

Filed under:

Biographies/Autobiographies,

Nonfiction,

Picture Books,

Women's history Tagged:

Creativity,

curiosity,

Lois Ehlert

The endearing little elephant featured in the Pomelo the Garden Elephant series keeps right on growing and investigating life’s myriad mysteries in Pomelo’s Big Adventure.

Pomelo has already learned about colors, opposites, and his own physical development. The cotton-candy pink pachyderm that started out being the size of a radish has now outlasted his favorite puffball (which first appeared in Pomelo Begins to Grow, 2011) and decides to travel afar.

With characteristic quirkiness, Ms. Bădescu reveals what Pomelo packs in his knapsack; he includes not only the practical (toothbrush, matches, a map) but also amusingly childish objects: a stone, crayons, and acorns. The elephant’s simple thinking process is demonstrated by his strategy of choosing his path by tossing a beribboned stone and then proceeding in that direction.

Throughout Pomelo’s Big Adventure, a gentle spirit of exploration leads the protagonist and the reader onward. Oversize pages filled with Mr. Chaud’s witty, bright drawings that pop amidst white pages reflect the elephant’s sense of curiosity and openness to possibilities.

Along the way, the author provides adults with fresh opportunities to discuss universal questions with children. For instance, consider the elephant’s approach to new experiences: “He takes the route such as it is: prickly, uphill, sticky, boring, surprising, lively, and … lost in the distance.” And later, when Pomelo encounters a shifty rat who dupes him into trading his valuable supplies for a wind-up car that promptly falls apart, the elephant feels the way anyone who’s been tricked might: rueful, uncertain, homesick. In the midst of a gray rain, though, he decides to march on, and the author points out, “We take many risks in life, of course, but Pomelo seems to have plunged into a world ruled by chance.”

Soon, Pomelo encounters a helpful old elephant who offers the determined explorer not only food but much-needed emotional guidance that will enable him to enjoy his journey. The mature mentor, called Papamelo, gathers wood and teaches the little one how to build a boat. And then, in his wisdom, he tells Pomelo, “It’s time to leave.”

When the pink elephant encounters danger, the memory of lessons learned from Papamelo, spur him on. A final double-page spread parades the unforeseen benefits of this hero’s courage and fortitude. In a glowing, cheerful scene, we see Pomelo on the beach at sunset with his new friend—a lively, freckled starfish eager to share joyous experiences. Young readers will no doubt anticipate further adventures celebrating this wildly unlikely pair.

Reprinted with permission from the New York Journal of Books

See also …

Filed under:

Animals,

Friendship,

Picture Books Tagged:

Benjamin Chaud,

Ramona Badescu

The endearing little elephant featured in the Pomelo the Garden Elephant series keeps right on growing and investigating life’s myriad mysteries in Pomelo’s Big Adventure.

Pomelo has already learned about colors, opposites, and his own physical development. The cotton-candy pink pachyderm that started out being the size of a radish has now outlasted his favorite puffball (which first appeared in Pomelo Begins to Grow, 2011) and decides to travel afar.

With characteristic quirkiness, Ms. Bădescu reveals what Pomelo packs in his knapsack; he includes not only the practical (toothbrush, matches, a map) but also amusingly childish objects: a stone, crayons, and acorns. The elephant’s simple thinking process is demonstrated by his strategy of choosing his path by tossing a beribboned stone and then proceeding in that direction.

Throughout Pomelo’s Big Adventure, a gentle spirit of exploration leads the protagonist and the reader onward. Oversize pages filled with Mr. Chaud’s witty, bright drawings that pop amidst white pages reflect the elephant’s sense of curiosity and openness to possibilities.

Along the way, the author provides adults with fresh opportunities to discuss universal questions with children. For instance, consider the elephant’s approach to new experiences: “He takes the route such as it is: prickly, uphill, sticky, boring, surprising, lively, and … lost in the distance.” And later, when Pomelo encounters a shifty rat who dupes him into trading his valuable supplies for a wind-up car that promptly falls apart, the elephant feels the way anyone who’s been tricked might: rueful, uncertain, homesick. In the midst of a gray rain, though, he decides to march on, and the author points out, “We take many risks in life, of course, but Pomelo seems to have plunged into a world ruled by chance.”

Soon, Pomelo encounters a helpful old elephant who offers the determined explorer not only food but much-needed emotional guidance that will enable him to enjoy his journey. The mature mentor, called Papamelo, gathers wood and teaches the little one how to build a boat. And then, in his wisdom, he tells Pomelo, “It’s time to leave.”

When the pink elephant encounters danger, the memory of lessons learned from Papamelo, spur him on. A final double-page spread parades the unforeseen benefits of this hero’s courage and fortitude. In a glowing, cheerful scene, we see Pomelo on the beach at sunset with his new friend—a lively, freckled starfish eager to share joyous experiences. Young readers will no doubt anticipate further adventures celebrating this wildly unlikely pair.

Reprinted with permission from the New York Journal of Books

See also …

Filed under:

Animals,

Friendship,

Picture Books Tagged:

Benjamin Chaud,

Ramona Badescu

With its bracing plot featuring a valiant, strong-willed girl who breaks the spell that transformed her brothers into swans, the Brothers Grimm shaped a fairy tale strange and potent enough to lure a contemporary audience.

contemporary audience.

In fairy-tale fashion, The Six Swans plays out in the landscape of a widowed father and children cursed or left to their own devices. The narrative opens in a great forest, where the king, chasing a deer, strays from his companions and cannot find his way out. An old woman who approaches him turns out to be a witch. She will show him the way only if he will agree to marry her beautiful daughter.

Fear compels the king to agree to this condition, but troubles loom. When he meets the young woman, he does not fall in love with her, despite her beauty; in fact, he “could not look at her without a secret sense of horror.”

Readers, too, will distrust the new queen, depicted by illustrator Gerda Raidt as having a haughty posture, a callous expression, and ice-blue gowns. Some will likely agree with the king’s peculiar decision to shield his six sons and one daughter from the stepmother by taking them to live in a lonely castle hidden so deeply in a forest that the king must use a magic ball of string to find the path leading to it.

A cheerful double-page spread depicts a leafy, bucolic scene there, with the kinder scampering, fishing, or swinging on a tree. In the background, we see their secret home, a pale three-story abode with a slate-gray roof, resembling a grand chateau of the Loire Valley rather than a German schloss.

The illustrator’s other somewhat puzzling choices include her image of the children’s badminton rackets, which have been traced to British military officers serving in British India in the mid-1800s. And one cannot help but wonder why the daughter, in her high-waisted dress, and the sons in their sailor whites look so Edwardian.

Often, too, the colored-pencil drawings seem tame (in contrast to Anne Yvonne Gilbert’s glorious artwork for The Wild Swans by Hans Christian Andersen), missing the intense drama of unfolding events. The moment when the wicked stepmother, who has discovered the hidden castle, turns the boys into swans should teem with a sense of disaster. Instead, we see an image of the sister, the lone child indoors on that unfortunate day, looking merely surprised as her brothers sprout feathers and rise in the sky.

Despite these incongruities, the illustrator offers a rich, symbolic rendering of the daughter’s heroic decision to reject her father’s decision to take her to his home in favor of setting out alone to search for her brothers. Here, we see the girl boldly abandoning the idyllic estate and entering a foreboding forest, drawn with gloomy gray strokes and dark shadows.

When at last the sister finds her siblings in a robbers’ den, they tell her they may shed their feathers for only a quarter of an hour every night, and then they become swans again. The curse can only be broken if she agrees to speak not a word for six years and to sew them six shirts made of starflowers.

Some might wonder what starflowers are (in his famous Grimms’ folktale anthology, Jack Zipes chose the word asters), but the translator has offered a pleasingly literal translation of the German word Sternenblumen, which the Brothers Grimm used, and so feels authentic. One of only a relatively few picture-book versions of “The Six Swans” published, this edition is smoothly translated by Anthea Bell, whose acclaimed work includes the French comic-book series Asterix, as well as the middle-school fantasies of Cornelia Funke (Inkworld trilogy).

Although she faithfully follows the fairy tale’s spirit and pacing, Ms. Bell has lightened up the story by omitting some of the gory details that unfurl. A handsome young king happens upon the girl in the forest, falls in love, and the two marry, even though she never speaks to him. This so displeases his mother that she steals the baby the queen bears—and the next two— until finally, the king agrees to let his wife be tried for murdering the children. She refuses to defend herself and is condemned to be burned at the stake.

While the Grimms’ version offers stark poetic justice for the wicked mother-in-law when the brothers’ spell is broken and the sister finally tells her husband she has been wrongly accused by the woman, this version relates that the wicked one is “taken away and locked up forever.”

The Six Swans will inspire many young readers and caring adults who crave tales highlighting heroines who do not resort to violence to save the day.

If you’re looking for a more engrossing reading experience, don’t miss the fabulous Naomi Lewis retelling of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Wild Swans, a slightly altered version of the Grimm brothers’ tale.

Also see my posts on Pullman’s anthology of Grimm folktales and on the dazzling Taschen anthology.

Also see my posts on Pullman’s anthology of Grimm folktales and on the dazzling Taschen anthology.

Filed under:

Folk and Fairy Tales,

Hero stories,

Picture Books

With its bracing plot featuring a valiant, strong-willed girl who breaks the spell that transformed her brothers into swans, the Brothers Grimm shaped a fairy tale strange and potent enough to lure a contemporary audience.

contemporary audience.

In fairy-tale fashion, The Six Swans plays out in the landscape of a widowed father and children cursed or left to their own devices. The narrative opens in a great forest, where the king, chasing a deer, strays from his companions and cannot find his way out. An old woman who approaches him turns out to be a witch. She will show him the way only if he will agree to marry her beautiful daughter.

Fear compels the king to agree to this condition, but troubles loom. When he meets the young woman, he does not fall in love with her, despite her beauty; in fact, he “could not look at her without a secret sense of horror.”

Readers, too, will distrust the new queen, depicted by illustrator Gerda Raidt as having a haughty posture, a callous expression, and ice-blue gowns. Some will likely agree with the king’s peculiar decision to shield his six sons and one daughter from the stepmother by taking them to live in a lonely castle hidden so deeply in a forest that the king must use a magic ball of string to find the path leading to it.

A cheerful double-page spread depicts a leafy, bucolic scene there, with the kinder scampering, fishing, or swinging on a tree. In the background, we see their secret home, a pale three-story abode with a slate-gray roof, resembling a grand chateau of the Loire Valley rather than a German schloss.

The illustrator’s other somewhat puzzling choices include her image of the children’s badminton rackets, which have been traced to British military officers serving in British India in the mid-1800s. And one cannot help but wonder why the daughter, in her high-waisted dress, and the sons in their sailor whites look so Edwardian.

Often, too, the colored-pencil drawings seem tame (in contrast to Anne Yvonne Gilbert’s glorious artwork for The Wild Swans by Hans Christian Andersen), missing the intense drama of unfolding events. The moment when the wicked stepmother, who has discovered the hidden castle, turns the boys into swans should teem with a sense of disaster. Instead, we see an image of the sister, the lone child indoors on that unfortunate day, looking merely surprised as her brothers sprout feathers and rise in the sky.

Despite these incongruities, the illustrator offers a rich, symbolic rendering of the daughter’s heroic decision to reject her father’s decision to take her to his home in favor of setting out alone to search for her brothers. Here, we see the girl boldly abandoning the idyllic estate and entering a foreboding forest, drawn with gloomy gray strokes and dark shadows.

When at last the sister finds her siblings in a robbers’ den, they tell her they may shed their feathers for only a quarter of an hour every night, and then they become swans again. The curse can only be broken if she agrees to speak not a word for six years and to sew them six shirts made of starflowers.

Some might wonder what starflowers are (in his famous Grimms’ folktale anthology, Jack Zipes chose the word asters), but the translator has offered a pleasingly literal translation of the German word Sternenblumen, which the Brothers Grimm used, and so feels authentic. One of only a relatively few picture-book versions of “The Six Swans” published, this edition is smoothly translated by Anthea Bell, whose acclaimed work includes the French comic-book series Asterix, as well as the middle-school fantasies of Cornelia Funke (Inkworld trilogy).

Although she faithfully follows the fairy tale’s spirit and pacing, Ms. Bell has lightened up the story by omitting some of the gory details that unfurl. A handsome young king happens upon the girl in the forest, falls in love, and the two marry, even though she never speaks to him. This so displeases his mother that she steals the baby the queen bears—and the next two— until finally, the king agrees to let his wife be tried for murdering the children. She refuses to defend herself and is condemned to be burned at the stake.

While the Grimms’ version offers stark poetic justice for the wicked mother-in-law when the brothers’ spell is broken and the sister finally tells her husband she has been wrongly accused by the woman, this version relates that the wicked one is “taken away and locked up forever.”

The Six Swans will inspire many young readers and caring adults who crave tales highlighting heroines who do not resort to violence to save the day.

If you’re looking for a more engrossing reading experience, don’t miss the fabulous Naomi Lewis retelling of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Wild Swans, a slightly altered version of the Grimm brothers’ tale.

Also see my posts on Pullman’s anthology of Grimm folktales and on the dazzling Taschen anthology.

Also see my posts on Pullman’s anthology of Grimm folktales and on the dazzling Taschen anthology.

Filed under:

Folk and Fairy Tales,

Hero stories,

Picture Books

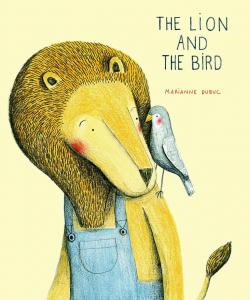

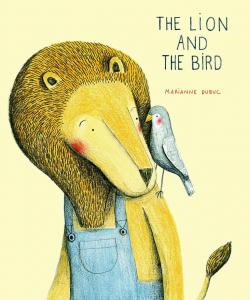

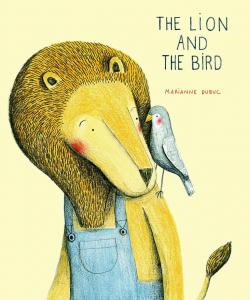

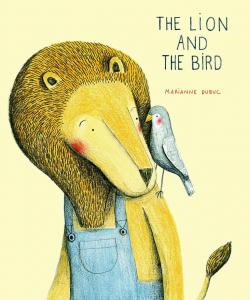

With its understated title and its placid cover image of a rosy-cheeked lion with a small gray bird on his shoulder, The Lion and the Bird is clearly not where the wild things are. And that’s just fin e.

e.

Instead, Canadian author/illustrator Marianne Dubuc uses simple language and a quiet palette of soft shades of tan, blue, and gray to evoke a calmer world where seasons and relationships evolve and where even the unlikeliest pair can become friends.

Dressed in denim overalls, Lion is hoeing one autumn day when a bird falls out of the sky and into his yard. Lion tenderly bandages the bird’s injured wing, and the other birds fly off without their fallen friend. No need to worry, Lion says, putting the bird atop his well-behaved mane. “You’re welcome to stay with me. There’s more than enough room for both of us.”

And so the two head to Lion’s mound-shaped home and begin their companionable life together. The author/illustrator gives readers both full-page and smaller, rough-shaped ovals of pencil drawings that show the friends falling into a sweet routine of sharing food, bedtime stories, and sleeping—Lion in a plain white bed and Bird nearby, tucked into a fuzzy pink bedroom slipper.

Winter brings snow, and the two have fun sledding and ice fishing together. “It snows and snows. But winter doesn’t feel all that cold with a friend.”

Change inevitably comes with spring, though, and Ms. Dubuc beautifully evokes the friends’ awareness that it’s time for Bird to rejoin the flock. Perched on a branch and pointing one wing toward the others, Bird looks at Lion. “Yes,” says Lion. “I know.” And just as Lion releases his friend, the author/illustrator lets white space nearly fill the next four pages.

Lion goes back to his daily routines while making adjustments; readers will note the single place setting at the table, the empty box by the fireplace, the uninhabited bedroom slipper. Soon it’s back to the garden for Lion, who takes pleasure in summer pastimes such as reading beneath a shade tree and fishing in a lake.

As fall returns, Lion can’t help but hope his friend will, too. The bird’s reappearance signifies the nature of friendship and the cycles of life, making for a satisfying ending that will nourish a sense of hope in young readers (especially ages 3 to 6).

Reprinted with permission from New York Journal of Books

See also …

With its understated title and placid cover image of a rosy-cheeked lion with a small gray bird on his shoulder, The Lion and the Bird is clearly not where the wild things are. And that’s just fine.

Instead, Ms. Dubuc, using simple language and a quiet palette of soft shades of tan, blue, and gray, envisions a calmer world where seasons and relationships evolve and where even the unlikeliest pair can become friends.

Dressed in denim overalls, Lion is hoeing one autumn day when a bird falls out of the sky and into his yard. Lion tenderly bandages the bird’s injured wing, and the other birds fly off without their fallen friend. No need to worry, Lion says, putting the bird atop his well-behaved mane. “You’re welcome to stay with me. There’s more than enough room for both of us.”

And so the two head to Lion’s mound-shaped home and begin their companionable life together. The author/illustrator gives readers both full-page and smaller, rough-shaped ovals of pencil drawings that show the friends falling into a sweet routine of sharing food, bedtime stories, and sleeping—Lion in a plain white bed and Bird nearby, tucked into a fuzzy pink bedroom slipper.

Winter brings snow, and the two have fun sledding and ice fishing together. “It snows and snows. But winter doesn’t feel all that cold with a friend.”

Change inevitably comes with spring, though, and Ms. Dubuc beautifully evokes the friends’ awareness that it’s time for Bird to rejoin the flock. Perched on a branch and pointing one wing toward the others, Bird looks at Lion. “Yes,” says Lion. “I know.” And just as Lion releases his friend, the author/illustrator lets white space nearly fill the next four pages.

Lion goes back to his daily routines while making adjustments; readers will note the single place setting at the table, the empty box by the fireplace, the uninhabited pink bedroom slippers. Soon it’s back to the garden for Lion, who takes pleasure in summer pastimes such as reading beneath a shade tree and fishing in a lake.

Fall returns, and Lion can’t help but hope his friend will, too. The bird’s reappearance signifies the nature of friendship and the cycles of life, making for a satisfying ending that young readers will relish.

- See more at: http://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/lion-and-bird#sthash.hqELM9t0.dpuf

Filed under:

Animals,

Friendship,

Peace stories,

Picture Books,

Tales of hospitality Tagged:

Change of seasons,

Marianne Dubuc

With its understated title and its placid cover image of a rosy-cheeked lion with a small gray bird on his shoulder, The Lion and the Bird is clearly not where the wild things are. And that’s just fin e.

e.

Instead, Canadian author/illustrator Marianne Dubuc uses simple language and a quiet palette of soft shades of tan, blue, and gray to evoke a calmer world where seasons and relationships evolve and where even the unlikeliest pair can become friends.

Dressed in denim overalls, Lion is hoeing one autumn day when a bird falls out of the sky and into his yard. Lion tenderly bandages the bird’s injured wing, and the other birds fly off without their fallen friend. No need to worry, Lion says, putting the bird atop his well-behaved mane. “You’re welcome to stay with me. There’s more than enough room for both of us.”

And so the two head to Lion’s mound-shaped home and begin their companionable life together. The author/illustrator gives readers both full-page and smaller, rough-shaped ovals of pencil drawings that show the friends falling into a sweet routine of sharing food, bedtime stories, and sleeping—Lion in a plain white bed and Bird nearby, tucked into a fuzzy pink bedroom slipper.

Winter brings snow, and the two have fun sledding and ice fishing together. “It snows and snows. But winter doesn’t feel all that cold with a friend.”

Change inevitably comes with spring, though, and Ms. Dubuc beautifully evokes the friends’ awareness that it’s time for Bird to rejoin the flock. Perched on a branch and pointing one wing toward the others, Bird looks at Lion. “Yes,” says Lion. “I know.” And just as Lion releases his friend, the author/illustrator lets white space nearly fill the next four pages.

Lion goes back to his daily routines while making adjustments; readers will note the single place setting at the table, the empty box by the fireplace, the uninhabited bedroom slipper. Soon it’s back to the garden for Lion, who takes pleasure in summer pastimes such as reading beneath a shade tree and fishing in a lake.

As fall returns, Lion can’t help but hope his friend will, too. The bird’s reappearance signifies the nature of friendship and the cycles of life, making for a satisfying ending that will nourish a sense of hope in young readers (especially ages 3 to 6).

Reprinted with permission from New York Journal of Books

See also …

With its understated title and placid cover image of a rosy-cheeked lion with a small gray bird on his shoulder, The Lion and the Bird is clearly not where the wild things are. And that’s just fine.

Instead, Ms. Dubuc, using simple language and a quiet palette of soft shades of tan, blue, and gray, envisions a calmer world where seasons and relationships evolve and where even the unlikeliest pair can become friends.

Dressed in denim overalls, Lion is hoeing one autumn day when a bird falls out of the sky and into his yard. Lion tenderly bandages the bird’s injured wing, and the other birds fly off without their fallen friend. No need to worry, Lion says, putting the bird atop his well-behaved mane. “You’re welcome to stay with me. There’s more than enough room for both of us.”

And so the two head to Lion’s mound-shaped home and begin their companionable life together. The author/illustrator gives readers both full-page and smaller, rough-shaped ovals of pencil drawings that show the friends falling into a sweet routine of sharing food, bedtime stories, and sleeping—Lion in a plain white bed and Bird nearby, tucked into a fuzzy pink bedroom slipper.

Winter brings snow, and the two have fun sledding and ice fishing together. “It snows and snows. But winter doesn’t feel all that cold with a friend.”

Change inevitably comes with spring, though, and Ms. Dubuc beautifully evokes the friends’ awareness that it’s time for Bird to rejoin the flock. Perched on a branch and pointing one wing toward the others, Bird looks at Lion. “Yes,” says Lion. “I know.” And just as Lion releases his friend, the author/illustrator lets white space nearly fill the next four pages.

Lion goes back to his daily routines while making adjustments; readers will note the single place setting at the table, the empty box by the fireplace, the uninhabited pink bedroom slippers. Soon it’s back to the garden for Lion, who takes pleasure in summer pastimes such as reading beneath a shade tree and fishing in a lake.

Fall returns, and Lion can’t help but hope his friend will, too. The bird’s reappearance signifies the nature of friendship and the cycles of life, making for a satisfying ending that young readers will relish.

- See more at: http://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/lion-and-bird#sthash.hqELM9t0.dpuf

Filed under:

Animals,

Friendship,

Peace stories,

Picture Books,

Tales of hospitality Tagged:

Change of seasons,

Marianne Dubuc

An adventurous spirit reaches new heights in Torben Kuhlmann’s debut picture book Lindbergh: The Tale of a Flying Mouse.

Any mouse with a swirling tail and a fervent wish to fly could snag a child’s interest, but Lindbergh immerses the reader in a fantastical world, with atmospheric, sepia-toned watercolors and pencil drawings and an imaginative plot with myriad historical links, portrayed with dramatic flair.

Intellectual curiosity propels the protagonist to take action, again and again. The furry, unnamed mouse camps out for months at a time in a library, reveling in leather-bound volumes conjured with a warm, vintage sepia palette. One day he emerges to discover he’s alone, as his friends have fled Hamburg after the “nightmarish” new mechanical mousetraps occupy homes.

Echoing the historic Charles Lindbergh 1927 transatlantic flight in reverse, the mouse decides he must fly to America. The author/illustrator, playing with the German word for bat, fledermaus, shows how our vivacious hero becomes inspired by observing bats. The rodent “carefully studied the strange flying relatives” and then sets out to construct his own flying contraption. Mr. Kuhlmann’s realistic pencil drawings recall Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches. Fittingly, we view the mouse’s sketch of a bat on one page and on the facing page, original designs for his own wings.

As with any inventor, the mouse must test his wings. Mr. Kuhlmann offers a lovely light-filled, drawn and painted scene of the Hamburg train station, with hurried travelers dressed in suits and hats. The eye lingers on the dramatic profile of the mouse atop the old clock as he anticipates takeoff. Although his attempt fails, the would-be pilot gains potentially useful information when he notices the trains get their power from steam.

Revisions lead to further improvements: wings and rudders. Readers will pore over the many humorous details that depict the miniature inventor’s thought process: how he pulls the shoelace from an old boot, how he peeps out of an old typewriter labeled Flieger (German for “flyer”), how he accumulates a multitude of springs and gears from timepieces.

The goggle-wearing mouse straps on his new and improved winged contraption and manages to fly briefly before crashing. Thanks to a photojournalist, the unusual pilot finds his way into the newspapers: “Hamburgs Fliegende Maus Gesichtet!” (Flying Mouse Spotted).

Stunningly, the next double-page spread shows large, orange-eyed owls studying the lead story and its photo of a mouse in midflight. Mr. Kuhlmann proceeds to ramp up the dramatic effect by providing subsequent images of the fierce predators as they spy on the mouse, even as he tinkers in his attic workshop.

The intrepid rodent receives a hero’s welcome when he eventually arrives in New York, and a mesmerized young Charles Lindbergh, with model airplane in hand, becomes inspired to aim high—or so it’s said in this alternate world. The engaging story is complemented by a short illustrated history of aviation, including a brief account of the American pilot who made history in his single-engine Spirit of St. Louis.

While longer than most picture books (mostly because of illustrations), Mr. Kuhlman’s Lindbergh soars with its distinctive artwork, spectacular details, and its bright little star. Highly recommended for ages 6 to 10.

Reprinted with permission from New York Journal of Books.

See also …

An adventurous spirit reaches new heights in Torben Kuhlmann’s debut picture book Lindbergh: The Tale of a Flying Mouse.

Any mouse with a swirling tail and a fervent wish to fly could snag a child’s interest, but Lindbergh immerses the reader in a fantastical world with atmospheric, sepia-toned watercolors and pencil drawings and an imaginative plot with myriad historical links portrayed with dramatic flair.

Intellectual curiosity propels the protagonist to take action again and again. The furry, unnamed mouse camps out for months at a time in a library, reveling in leather-bound volumes conjured with a warm, vintage sepia palette. One day he emerges to discover he’s alone, as his friends have fled Hamburg after the “nightmarish” new mechanical mousetraps occupy homes.

Echoing the historic Charles Lindbergh 1927 transatlantic flight in reverse, the mouse decides he must fly to America. The author/illustrator, playing with the German word for bat, fledermaus, shows how our vivacious hero becomes inspired by observing bats. The rodent “carefully studies the strange flying relatives” and then sets out to construct his own flying contraption. Kuhlmann’s realistic pencil drawings recall Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches. Fittingly, we view the mouse’s sketch of a bat on one page and on the facing page, original designs for his own wings.

As with any inventor, the mouse must test his wings. Kuhlmann offers a lovely light-filled, drawn and painted scene of the Hamburg train station, with hurried travelers dressed in suits and hats. The eye lingers on the dramatic profile of the mouse atop the old clock as he anticipates takeoff. Although his attempt fails, the would-be pilot gains potentially useful information when he notices the trains get their power from steam.

Revisions lead to further improvements: wings and rudders. Readers will pore over the many humorous details that depict the miniature inventor’s thought process: how he pulls the shoelace from an old boot, how he peeps out of an old typewriter labeled Flieger (German for “flyer”), how he accumulates a multitude of springs and gears from timepieces.

The goggle-wearing mouse straps on his new and improved winged contraption and manages to fly briefly before crashing. Thanks to a photojournalist, the unusual pilot finds his way into the newspapers: “Hamburgs Fliegende Maus Gesichtet!” (Flying Mouse Spotted).

Stunningly, the next double-page spread shows large, orange-eyed owls studying the lead story and its photo of a mouse in midflight. Kuhlmann proceeds to ramp up the dramatic effect by providing subsequent images of the fierce predators as they spy on the mouse, even as he tinkers in his attic workshop.

SPOILER ALERT: The intrepid rodent receives a hero’s welcome when he eventually arrives in New York, and a mesmerized young Charles Lindbergh, with model airplane in hand, becomes inspired to aim high—or so it’s said in this alternate world. The engaging story is complemented by a short illustrated history of aviation, including a brief account of the American pilot who made history in his single-engine Spirit of St. Louis.

While longer than most picture books (mostly because of illustrations), Kuhlman’s Lindbergh soars with its distinctive artwork, spectacular details, and its bright little star.

- See more at: http://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/lindbergh-tale-flying-mouse#sthash.rgHcP9Ug.dpuf

An adventurous spirit reaches new heights in Torben Kuhlmann’s debut picture book Lindbergh: The Tale of a Flying Mouse.

Any mouse with a swirling tail and a fervent wish to fly could snag a child’s interest, but Lindbergh immerses the reader in a fantastical world with atmospheric, sepia-toned watercolors and pencil drawings and an imaginative plot with myriad historical links portrayed with dramatic flair.

Intellectual curiosity propels the protagonist to take action again and again. The furry, unnamed mouse camps out for months at a time in a library, reveling in leather-bound volumes conjured with a warm, vintage sepia palette. One day he emerges to discover he’s alone, as his friends have fled Hamburg after the “nightmarish” new mechanical mousetraps occupy homes.

Echoing the historic Charles Lindbergh 1927 transatlantic flight in reverse, the mouse decides he must fly to America. The author/illustrator, playing with the German word for bat, fledermaus, shows how our vivacious hero becomes inspired by observing bats. The rodent “carefully studies the strange flying relatives” and then sets out to construct his own flying contraption. Kuhlmann’s realistic pencil drawings recall Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches. Fittingly, we view the mouse’s sketch of a bat on one page and on the facing page, original designs for his own wings.

As with any inventor, the mouse must test his wings. Kuhlmann offers a lovely light-filled, drawn and painted scene of the Hamburg train station, with hurried travelers dressed in suits and hats. The eye lingers on the dramatic profile of the mouse atop the old clock as he anticipates takeoff. Although his attempt fails, the would-be pilot gains potentially useful information when he notices the trains get their power from steam.

Revisions lead to further improvements: wings and rudders. Readers will pore over the many humorous details that depict the miniature inventor’s thought process: how he pulls the shoelace from an old boot, how he peeps out of an old typewriter labeled Flieger (German for “flyer”), how he accumulates a multitude of springs and gears from timepieces.

The goggle-wearing mouse straps on his new and improved winged contraption and manages to fly briefly before crashing. Thanks to a photojournalist, the unusual pilot finds his way into the newspapers: “Hamburgs Fliegende Maus Gesichtet!” (Flying Mouse Spotted).

Stunningly, the next double-page spread shows large, orange-eyed owls studying the lead story and its photo of a mouse in midflight. Kuhlmann proceeds to ramp up the dramatic effect by providing subsequent images of the fierce predators as they spy on the mouse, even as he tinkers in his attic workshop.

SPOILER ALERT: The intrepid rodent receives a hero’s welcome when he eventually arrives in New York, and a mesmerized young Charles Lindbergh, with model airplane in hand, becomes inspired to aim high—or so it’s said in this alternate world. The engaging story is complemented by a short illustrated history of aviation, including a brief account of the American pilot who made history in his single-engine Spirit of St. Louis.

While longer than most picture books (mostly because of illustrations), Kuhlman’s Lindbergh soars with its distinctive artwork, spectacular details, and its bright little star.

- See more at: http://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/lindbergh-tale-flying-mouse#sthash.rgHcP9Ug.dpuf

An adventurous spirit reaches new heights in Torben Kuhlmann’s debut picture book Lindbergh: The Tale of a Flying Mouse.

Any mouse with a swirling tail and a fervent wish to fly could snag a child’s interest, but Lindbergh immerses the reader in a fantastical world with atmospheric, sepia-toned watercolors and pencil drawings and an imaginative plot with myriad historical links portrayed with dramatic flair.

Intellectual curiosity propels the protagonist to take action again and again. The furry, unnamed mouse camps out for months at a time in a library, reveling in leather-bound volumes conjured with a warm, vintage sepia palette. One day he emerges to discover he’s alone, as his friends have fled Hamburg after the “nightmarish” new mechanical mousetraps occupy homes.

Echoing the historic Charles Lindbergh 1927 transatlantic flight in reverse, the mouse decides he must fly to America. The author/illustrator, playing with the German word for bat, fledermaus, shows how our vivacious hero becomes inspired by observing bats. The rodent “carefully studies the strange flying relatives” and then sets out to construct his own flying contraption. Kuhlmann’s realistic pencil drawings recall Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches. Fittingly, we view the mouse’s sketch of a bat on one page and on the facing page, original designs for his own wings.

As with any inventor, the mouse must test his wings. Kuhlmann offers a lovely light-filled, drawn and painted scene of the Hamburg train station, with hurried travelers dressed in suits and hats. The eye lingers on the dramatic profile of the mouse atop the old clock as he anticipates takeoff. Although his attempt fails, the would-be pilot gains potentially useful information when he notices the trains get their power from steam.

Revisions lead to further improvements: wings and rudders. Readers will pore over the many humorous details that depict the miniature inventor’s thought process: how he pulls the shoelace from an old boot, how he peeps out of an old typewriter labeled Flieger (German for “flyer”), how he accumulates a multitude of springs and gears from timepieces.

The goggle-wearing mouse straps on his new and improved winged contraption and manages to fly briefly before crashing. Thanks to a photojournalist, the unusual pilot finds his way into the newspapers: “Hamburgs Fliegende Maus Gesichtet!” (Flying Mouse Spotted).

Stunningly, the next double-page spread shows large, orange-eyed owls studying the lead story and its photo of a mouse in midflight. Kuhlmann proceeds to ramp up the dramatic effect by providing subsequent images of the fierce predators as they spy on the mouse, even as he tinkers in his attic workshop.

SPOILER ALERT: The intrepid rodent receives a hero’s welcome when he eventually arrives in New York, and a mesmerized young Charles Lindbergh, with model airplane in hand, becomes inspired to aim high—or so it’s said in this alternate world. The engaging story is complemented by a short illustrated history of aviation, including a brief account of the American pilot who made history in his single-engine Spirit of St. Louis.

While longer than most picture books (mostly because of illustrations), Kuhlman’s Lindbergh soars with its distinctive artwork, spectacular details, and its bright little star.

- See more at: http://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/lindbergh-tale-flying-mouse#sthash.rgHcP9Ug.dpuf

Filed under:

Animals,

Picture Books Tagged:

Torben Kuhlmann

An adventurous spirit reaches new heights in Torben Kuhlmann’s debut picture book Lindbergh: The Tale of a Flying Mouse.

Any mouse with a swirling tail and a fervent wish to fly could snag a child’s interest, but Lindbergh immerses the reader in a fantastical world, with atmospheric, sepia-toned watercolors and pencil drawings and an imaginative plot with myriad historical links, portrayed with dramatic flair.

Intellectual curiosity propels the protagonist to take action, again and again. The furry, unnamed mouse camps out for months at a time in a library, reveling in leather-bound volumes conjured with a warm, vintage sepia palette. One day he emerges to discover he’s alone, as his friends have fled Hamburg after the “nightmarish” new mechanical mousetraps occupy homes.

Echoing the historic Charles Lindbergh 1927 transatlantic flight in reverse, the mouse decides he must fly to America. The author/illustrator, playing with the German word for bat, fledermaus, shows how our vivacious hero becomes inspired by observing bats. The rodent “carefully studied the strange flying relatives” and then sets out to construct his own flying contraption. Mr. Kuhlmann’s realistic pencil drawings recall Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches. Fittingly, we view the mouse’s sketch of a bat on one page and on the facing page, original designs for his own wings.

As with any inventor, the mouse must test his wings. Mr. Kuhlmann offers a lovely light-filled, drawn and painted scene of the Hamburg train station, with hurried travelers dressed in suits and hats. The eye lingers on the dramatic profile of the mouse atop the old clock as he anticipates takeoff. Although his attempt fails, the would-be pilot gains potentially useful information when he notices the trains get their power from steam.

Revisions lead to further improvements: wings and rudders. Readers will pore over the many humorous details that depict the miniature inventor’s thought process: how he pulls the shoelace from an old boot, how he peeps out of an old typewriter labeled Flieger (German for “flyer”), how he accumulates a multitude of springs and gears from timepieces.