new posts in all blogs

Viewing Blog: , Most Recent at Top

Results 1 - 25 of 25

Statistics for

Number of Readers that added this blog to their MyJacketFlap:

By: Lizzie Ross,

on 3/25/2016

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

reading,

History,

Adventure,

Graphic Novel,

Mystery,

Humorous,

Travel book,

Robin Sloan,

PG Wodehouse,

Little Free Library,

Allie Brosh,

Donald Culross Peattie,

RA Dick,

Wilbur Bassett,

Add a tag

When I haven’t the energy to read Proust, I read something else. In that respect, I’m no different from anyone else. But the other day my daughter commented on how strange it was that I was sitting on the couch reading one book while another lay at my side — after reading one for a few minutes, I would switch to the other, and after a while back again to the first. This went on for some time. I suspect this reading habit isn’t unusual either.

I can’t explain the thinking that forces the switch, nor even my choice of which books to read simultaneously. When my daughter made her comment, I was tag-reading Robin Sloan’s Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore and Allie Brosh’s Hyperbole and a Half. Perhaps it was the yellow covers (but only Sloan’s book glows in the dark). Perhaps it was because I’d just picked up both at one of my local Little Free Libraries (there are 4 within a 5-minute walk of my apartment). Each book is an easy and enjoyable read, but I found Brosh’s work much more profound, despite her purposefully childish drawings. Brosh’s memoir began as a blog (still available here); for the book she created some new episodes but also included her immensely famous stories about her 18-month bout with depression. Rightfully hailed as one of the best depictions of this terrible ailment, Brosh’s book ought to be required reading for everyone.

I can’t explain the thinking that forces the switch, nor even my choice of which books to read simultaneously. When my daughter made her comment, I was tag-reading Robin Sloan’s Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore and Allie Brosh’s Hyperbole and a Half. Perhaps it was the yellow covers (but only Sloan’s book glows in the dark). Perhaps it was because I’d just picked up both at one of my local Little Free Libraries (there are 4 within a 5-minute walk of my apartment). Each book is an easy and enjoyable read, but I found Brosh’s work much more profound, despite her purposefully childish drawings. Brosh’s memoir began as a blog (still available here); for the book she created some new episodes but also included her immensely famous stories about her 18-month bout with depression. Rightfully hailed as one of the best depictions of this terrible ailment, Brosh’s book ought to be required reading for everyone.

Mr. Penumbra‘s appearance was fortuitous, for I had just added it to my list of books to find and read. I was disappointed by the ending, but not the way that Kat, the Googler, is. (I’m trying not to include any spoilers here). It just seemed like a shaggy dog tale — a lot of build-up to a nearly anticlimactic ending. But I’m still keeping the book (the cover glows in the dark!). And I wouldn’t mind finding a bookstore like Mr. Penumbra’s, and if a group like the Unbroken Spine offered me membership, I’d grab it. A love of books and reading and puzzles is clear throughout this weird little mystery.

Another pairing: a compendium of P. G. Wodehouse golf tales with an obscure history of a village in Provence, again both picked up at my Little Free Library. Peattie’s Immortal Village tells of the city of Vence, from pre-historic times to the late-1920s. Botanist and author of a range of books, Peattie fell in love with Vence when he lived there for a few years. Before leaving the little city, he was inspired to write this book, which was then privately printed in France. In 1945, in response to the ravages of WWII, he brought out this American edition, with Paul Landacre’s gorgeous woodblock illustrations. He hoped it would teach readers, as they considered the aftermath of war, that

Another pairing: a compendium of P. G. Wodehouse golf tales with an obscure history of a village in Provence, again both picked up at my Little Free Library. Peattie’s Immortal Village tells of the city of Vence, from pre-historic times to the late-1920s. Botanist and author of a range of books, Peattie fell in love with Vence when he lived there for a few years. Before leaving the little city, he was inspired to write this book, which was then privately printed in France. In 1945, in response to the ravages of WWII, he brought out this American edition, with Paul Landacre’s gorgeous woodblock illustrations. He hoped it would teach readers, as they considered the aftermath of war, that

it is not insignificant to learn that this little Provençal town, once situated on a dangerous frontier, was destroyed again and again by barbarians and torn by internecine quarrel, and yet it was rebuilt. It is worth while to remember that nothing material is indestructible, but the spirit in man is.

Peattie’s writing reveals a 1920s racial sensibility, and the mishmash of kings, queens, nobility, invaders and townspeople in the Middle Ages is a challenge to keep track of. Yet there can be no confusion about Peattie’s appreciation for the people and environment in this “forgotten corner of Provence”.

About Wodehouse, I will say only that I never expected to laugh so often while reading a book of stories whose connecting thread was a love for the game of golf, about which I agree with whoever quipped “a good walk spoiled”.

Gustave Moreau, Jupiter and Semele

Within a Budding Grove, pp. 528-533.

I still have the 5-year-old notes for these pages, but to ease the task of getting back into reading Proust himself (rather than just my old blog posts and some books about his novel) I’ve backtracked. Re-entry completed.

I’m sure that somewhere there’s an annotated edition of Proust’s RTP, no doubt with more annotations than text. (Shattuck refers to a recent French edition of 7500 pages, which includes all Proust’s drafts and rejected materials, as well as critical essays, etc. etc. Shattuck rightly posits that if it wasn’t good enough for Proust to include in the published version, then we probably don’t need to know about it.)

I’m having fun, however, creating my own annotations. Moreau’s art work (left) is a case in point. Only a detour through the Wikiverse allowed me to fully appreciate how a fleeting reference to this painting works. Still at Balbec, Marcel sees his grandmother’s friend, Mme de Villeparisis, showing concern for Marcel’s father, in a way that “shewed her this one man so large among all the rest quite small, like that Jupiter to whom Gustave Moreau gave, when he portrayed him by the side of a weak mortal, a superhuman stature.” Behind this reference to Roman mythology lie jealousy, betrayal, murder. But what’s more interesting to me is that Moreau’s painting dates from AFTER Marcel’s visit to Balbec (Marcel Sprinker* places the Balbec visit as sometime between 1894 and 1896-7), thus reminding me of the importance of differentiating between the young Marcel and the older Narrator. Each tells a portion of RTP, but the line between them is so smooth as to be almost invisible.

The quote about Moreau, for instance, comes at the end of the paragraph below. Can you pinpoint where Marcel’s voice changes to the Narrator’s?

I asked myself by what strange accident, in the impartial glass through which Mme. de Villeparisis considered, from a safe distance, the bustling, tiny, purposeless agitation of the crowd of people whom she knew, there had come to be inserted at the spot through which she observed my father a fragment of prodigious magnifying power which made her see in such high relief and in the fullest detail everything that there was attractive about him, the contingencies that were obliging him to return home, his difficulties with the customs, his admiration for El Greco, and, altering the scale of her vision, shewed her this one man so large among all the rest quite small, like that Jupiter to whom Gustave Moreau gave, when he portrayed him by the side of a weak mortal, a superhuman stature.

That sentence appears to begin with Marcel’s POV (“I asked myself”); he’s astonished that such a great lady should be aware of his father. Yet almost immediately the language takes on the detailed complexity of the Narrator’s long-after-the-fact memory. The Jupiter reference finally confirms that a shift has occurred (how could Marcel have known about a painting not yet or only recently completed, and therefore not exhibited?).

Why is noting these shifts important, especially when Proust disguises them so well? It has to do with what I reported in an earlier post — the many selves. The much older Narrator is clearly not the same person as Marcel. It also has to do with the entire point of the novel, which I’ll write about when I get to the end of it myself (sometime in December of this year, if all goes well).

A final note about Proust’s titles: Moncrieff translated À la recherche du temps perdu as “A Remembrance of Things Past” (from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 30), but not everyone has been happy with that. In fact, I think most experts dislike it immensely. A preferred version is the more literal “In Search of Time Lost”, although I don’t like how this drops the rhythm of”recherche”, as well as its implied meaning of “searching again”. Montcrieff at least holds on to that subtle prefix, re-.

For the second volume’s À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs, which ought to be “In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower”, Montcrieff gave us “Within a Budding Grove”. Was Proust’s appreciation of young girls flowering into puberty too creepy for Montcrieff? What to do? I’m taking the easy route by sticking to the version I have, Montcrieff’s original (1924), with all its flaws. It’ll do.

*Michael Sprinker, History and Ideology in Proust (1998), p. 96.

By: Lizzie Ross,

on 3/18/2016

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

2016 Goals,

Marcel Proust,

Add a tag

The final reblogging from 5 years ago.

Within a Budding Grove, 514-528

Queen Ranavalo III of Madagascar

One of the perks of reading Proust is finding out about obscure personages. Although his main characters are his own creations (albeit based on real people), he sprinkles his stories with references to historical figures, references that seem arbitrary — perhaps the author’s version of “Tell Sparta people”.

Queen Ranavalona is one — an obscure ruler of Madascar when the French colonized the island; they eventually deposed her in 1897. She was exiled to Algeria but spent part of each year in Paris.

Her name comes up as Marcel talks about his and his grandmother’s position at the hotel in Balbeque. Recall, from another post, that the hotel’s guests are rather snobbish and eager to comment on everyone else’s status and behavior. Marcel is dissatisfied with his position at the bottom of the heap and misses the notice of people like M and Mme Swann. And then,

… mere chance put into our hands, my grandmother’s and mine, the means of giving ourselves an immediate distinction in the eyes of all the other occupants of the hotel. On that first afternoon, at the moment when the old lady came downstairs from her room, producing, thanks to the footman who preceded her, the maid who came running after her with a book and a rug that had been left behind, a marked effect upon all who beheld her and arousing in each of them a curiosity from which it was evident that none was so little immune as M. de Stermaria, the manager leaned across to my grandmother and, from pure kindness of heart (as one might point out the Shah, or Queen Ranavalo to an obscure onlooker who could obviously have no sort of connexion with so mighty a potentate, but might be interested, all the same, to know that he had been standing within a few feet of one) whispered in her ear, “The Marquise de Villeparisis!” while at the same moment the old lady, catching sight of my grandmother, could not repress a start of pleased surprise. (p. 519)

Of course Marcel’s grandmother and the Marquise know each other, but for complicated reasons they pretend not to, and Marcel must continue to squirm at the low end of the esteem scale. His chance to gain notice must pass, and he seethes with frustration. Oh, the ignominy!

The Narrator gives it all a spin so funny, I actually laughed out loud. Marcel is so self-conscious, as he walks among these people, that he can’t stop thinking about them not thinking about him:

Alas for my peace of mind, I had none of the detachment that all these people shewed. To many of them I gave constant thought; I should have liked not to pass unobserved by a man with a receding brow and eyes that dodged between the blinkers of his prejudices and his education … (p. 517)

Marcel can’t bear that he doesn’t stand out in this crowd of blinkered people with their low brows and low educations, and he is pleased when his grandmother and the Marquise finally deign to recognize and speak to each other. You can almost hear Marcel’s sigh of pleasure. Now people will look at him and think, “He must be somebody!”

I hope that most people, upon reaching adulthood, are relieved to discover that they can pass through the world for the most part unnoticed. How perceptive of Proust to make the young Marcel so self-conscious that he’s actually uncomfortable if people aren’t looking at him (with admiration and envy, of course) — as if his very existence depended on their noting his actions and wondering, “Who could that intelligent, sophisticated, handsome, well-dressed young man be?”

As Maurice Chevalier sings in Gigi, “I’m so glad that I’m not young anymore.”

Back in 2010-11, while working my way through 500+ pages of tiny print (I’ve just counted — 48 lines per page), I complained a bit about the lack of illustrations in some other books. I’m amused now that I never had that thought regarding Proust, and even now I can’t imagine how it might be illustrated without interrupting the experience of reading.

At any rate, my complaints paid off with a useful tip from a reader, as you’ll find out. This post was originally titled, “Why aren’t there more illustrations?”

Charles Ephrussi, by Jean Patricot, 1905, courtesy Wikipedia

When I first moved to NYC, in the mid-1970s, a neighbor pulled out a recently published edition of The American Heritage Dictionary and asked me what its one drawback was. I’ve always loved how the editors had designed that dictionary, and I could see nothing wrong with it: etymologies, definitions, usage guidance, breakdown of shades of meaning among synonyms (example: break, crack, fracture, rupture, burst, split, splinter, shatter, shiver, smash, and crush, all carefully delineated in a brief paragraph). So much information in one book. It seemed perfect to me.

My friend’s complaint? Not enough pictures. The margins of a page could hold as many of four photos or diagrams, but many have only one and too many have none at all.

I can’t look at a dictionary now without thinking of my erstwhile neighbor, and a non-fiction book with a stingy few illustrations makes me wonder why more weren’t included.

Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

de Waal’s The Hare with Amber Eyes is one such book. I’m loving it, although as the netsuke de Waal is following move to Vienna we have to leave Charles Swann/Ephrussi in Paris, and I was so enjoying all those overlaps.

Towards the end of the chapter on Charles, de Waal describes Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party and says that the top-hatted man at the rear, with his back to us, is his great uncle Charles Ephrussi! Well, Edmund? Why didn’t you include a reproduction? Why must I go through my art books hoping that one would have included it? (I was lucky and found one.)

Titian, Woman with a Mirror

Yes, yes, I know. Illustrations add to the expense of a book and better images than most books can produce are just a few clicks away on the web. If I could be more satisfied with each author’s descriptions of these pictures, I’d be a happier reader all around. But my mind wants to “see”, and so I pause in my reading to look something up.

Now, as I read Proust, I’ll be able to see Charles Ephrussi (and imagine Louise Cahen D’Anvers, for I’ve been unable to find any online drawing or painting of her; the closest available is Titian’s Woman with a Mirror).

L Cahen d’Anvers, by Bonnat, Courtesy Chapitre.com

BTW: the Getty Museum blog has a post about de Waal’s memoir.

And then, thanks to a follower, I was able to find a portrait of Louise Cahen d’Anvers, one possible model for Mme Swann. Oh, Odette, you look so very sweet here. Is this the image Marcel (and the Narrator) carried of you for so long? Does this innocent profile mask a colorful and notorious history?

Renoir, Little Irene

But wait. There’s much more information these days on the internet (it’s impossible to keep up). Louise and her husband Louis commissioned Renoir to paint a portrait of their daughter, Irène. Evidently, her parents were so unhappy with the painting that they hung it in the servants’ quarters and paid only 1500 francs. Renoir called the family “stingy”. If you’re curious, you can learn more about Louise and Irene here. I’m satisfied that this portrait reveals Gilberte, its background of shrubbery dappled with light looking like the gardens where Marcel first met Mme Swann’s daughter.

One last detour on my journey through past Proust posts, to a novel whose title reveals its relevance.

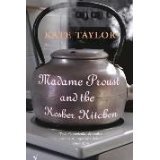

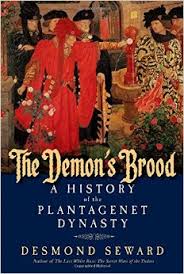

Madame Proust and the Kosher Kitchen (2003), Kate Taylor, 457 pp.

Madame Proust and the Kosher Kitchen (2003), Kate Taylor, 457 pp.

This novel, set in three time periods, is about women and how they cope with frustrated love, parenting, artistic creation, and, most importantly, anti-semitism — echoing Proust’s themes, but from the viewpoint of, say, Gilberte or Marcel’s mother.

Alfred Dreyfus

Marie Prevost, the main character, is a Canadian translator reading through Madame Proust’s journals and suffering from unrequited love — the object of her desire is Max, son of Sarah, daughter of parents killed at Auschwitz (and also distantly related to Mme Proust). Through Marie, we learn about Mme Proust, who worries about the bohemian life of her odd son, Marcel, at a time when all of France is arguing the case of Dreyfus. It is also through Marie that we learn about Sarah, sent from Paris to foster parents in Canada, saving her from the death camps but causing an anomie no one seems able to break through.

The parallels in the three stories are ingenious (causing comparison to Michael Cunningham’s The Hours), some you might guess right away and others only as they carefully unfold in the plot.

Marcel Proust, seated

Taylor jolts us back and forth between three time periods. We see late 19th- and early 20th century Paris through Mme Proust’s journals (Taylor’s own creation, and so well done I can’t believe they don’t sit somewhere in a French archive). Anyone at all familiar with Marcel’s great work will note the clues to its genesis. For instance, at one point, as the 19th century is drawing to a close, Mme Proust writes in her journal:

Marcel was pointing out that when you are a child waiting for father to come home and lunch to be served, time seems to drag on forever, but when you are an adult, and want to write a letter, and see a friend, and buy new gloves all in the same afternoon, it rushes by, and there is never enough of it. “How does the year or the century make any difference to how we perceive the time to pass?”

In the Jewish neighborhoods of mid-20th-century Toronto, reeling from WWII and the horrors of the concentration camps, are where we find Sarah, unable to connect to anyone, for decades suffering the shock of the separation from her parents. The modern setting gives us Marie’s life in Toronto and her journey to Paris, where she has to confront her own disappointments.

It’s as though Taylor is allowing us to put together a jigsaw puzzle, handing us just a few pieces at a time. At first, none of the pieces fit, but eventually patterns emerge, and at the end we have a detailed picture of lives that feed into each other. Some might argue that the links are too neat, too coincidental — but this is the author’s prerogative. Life often is coincidental, dependent on the daily accidents of crossed paths and shared desires.

Père Lachaise

This novel is a beautiful homage to Proust’s epic, to love and memory, to desire and loss. It begins and ends at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, a must-see for any fan of literature visiting Paris. (In The Innocents Abroad, Mark Twain calls it “the honored resting-place of some of [France’s] greatest and best children.”) You’ll want to go there after reading this book. If you do, take a few pebbles to place on the graves you visit.

By: Lizzie Ross,

on 3/15/2016

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Marcel Proust,

2016 Goals,

Add a tag

I’m nearing the end of these posts from the past (I think). However many remain, though, I’m determined to end this week with real-time reading and blogging.

Within a Budding Grove, pp. 504-514

Saint Blandina, courtesy SaintsSPQN.com

The only thing to report about these 10 pages is that Marcel has arrived at Balbec Plage, had a physical collapse, been rescued by his indulgent grandmother (“… be sure you knock on the wall if you want anything in the night”), and recovered enough to mingle with other guests at the hotel and comment on their behavior.

For example:

… the barrister and his friends could not exhaust their flow of sarcasm on the subject of a wealthy old lady of title, because she never moved anywhere without taking her whole household with her. Whenever the wives of the solicitor and the magistrate saw her in the dining-room at mealtimes they put up their glasses and gave her an insolent scrutiny, as minute and distrustful as if she had been some dish with a pretentious name but a suspicious appearance which, after the negative result of a systematic study, must be sent away with a lofty wave of the hand and a grimace of disgust.

On a related topic, I find it impossible to read one book at a time. No, I’m not like a two-fisted eater, with a book in each hand as my eyes alternate between the two. But I have a couple of books next to my couch, that I read in the afternoon or evening, and three more by my bed, that I read at night or when I wake up. When I get bored with one, I switch to another.

Bored with a book? As Spongebob would say, “Those words! I didn’t know you could use them together in one sentence!”

But, yes, bored. Every book has its slow moments, and Proust’s has what seems like more than its fair share. All this is to say that, although it may look as though I’m devoted to Marcel and carefully focused on the 10 to 20 pages I can read each week, it would be misrepresenting the truth. I’m actually a very fickle reader. If Proust were the only thing I was reading these days, I’d have finished the two volumes/seven novels long ago.

Busy, busy, busy.

Early 2011, my alternate reading consisted of Diana Wynne Jones, Cornelia Funke, Salman Rushdie, Sara Zarr, and I don’t even remember what else. These days, it’s a set of obscure books, which I’ll be happy to introduce you to, but not today.

Another promise to myself this year is to write some short fiction, so I’m trying an experiment: one short story per month (most are going up on Wattpad). Let’s see how long I can keep this up.

Another promise to myself this year is to write some short fiction, so I’m trying an experiment: one short story per month (most are going up on Wattpad). Let’s see how long I can keep this up.

In 2013, my sister sent me this card (download and enlarge for a better view); it inspired the following.

Flatiron’s Walk

The snow was deep when Flatiron set out for Invermere. He’d been tempted to stay in, a bowl of hot porridge in his lap as he toasted his feet on the hearth. The wind had picked up overnight, and its claws were searching in every crack for a way into his cottage. He knew that if he went outside his walls, it would tear through his layers of cloak, clothing and undergarments to freeze his skin.

Yet he needed to check his mail. A certain package ought to be waiting for him in the cubby, third from the left and five rows down, behind Mrs. Foresight’s thin lips and fearsome bulk at the corner shop in the village that lay, under banks of snow, just over the Hill. Through the thick window in his front door, he could make out the blurred image of a tree’s massive branches waving at him as he pulled his snowshoes from their rack.

While wrapping his scarf around his neck, Flatiron hummed a summery tune. He recalled how the hottest day of the previous August had scorched his bare head while he’d weeded the snapdragons. As usual, the memory didn’t warm him.

“Cheer-io!” he called out, though anyone else would wonder who he was cheer-io-ing. Flatiron lived alone.

The door banging shut sounded like “good riddance!”

“Yes, I know. You’re tired of me.” Flatiron heard the bolt shoot across on the inside. “At least I’m doing something productive!” he shouted through the thick door before turning up the path to open his gate. He paused a moment. The tree that had waved at him stood still, even in the wind. Its dark branches, silhouetted against the sky, looked like cracks in river ice.

Then, with a creak, the gate swung to behind him, shoving him into the world.

Behind him, a window curtain tweaked, but Flatiron pretended not to notice. “You’ll be lucky if I’m back before supper. It ain’t no picnic, walking to Invermere in all this. A good horse and sleigh would be worth its season’s feed, but no.” His voice rose two octaves. “‘Can’t afford it, too rich for us, we aren’t the aristocracy.’ Pah! Anybody’d think we were chimney sweeps.”

The deep whiteness soaked up his words so that not even the parliament of owls, hunkered down in the copse on his left, heard him. Flakes of snow, in a windy fluster, eddied around him.

He muttered as he shuffled along, his snowshoes leaving a slurred track. “There’s never an ‘enjoy your walk’ or ‘my regards to Mrs. Foresight.’” He leaned into the wind, and his words whipped past his ears, only to get caught in the few remaining strands of hair that trailed from his woolen cap. He tucked them under his collar, where they melted into soft whispers that warmed his neck.

Invermere lay to the southwest, and the sun would have been in his eyes if not for the thin clouds moving in from the sea. The muted light exaggerated the bleak landscape. Bare branches in the copse scratched against the low sky. They stretched towards Flatiron as he shuffled past, and he fought off an urge to swat at them. The sky seemed to sink lower and lower, as if to enfold him in a damp blanket.

He shivered.

Off to his right, Bearded Tor sheared steeply upward. Sharp pinnacles cleaved the sky, shredding the clouds that hung about the peaks. “Like me, old man, you’re losing your hair,” Flatiron commented.

A herd of black-nosed sheep clustered against the other side of a stone wall. They baa-ed and thrust their heads into the air. Steam gathered into a darkening cloud over them.

“You’ll start your own blizzard, if you don’t watch out,” he warned them.

For a moment the sheep held their breaths, puzzling out a response, and the cloud dispersed in the wind. But, coming up with nothing, the animals exhaled, blowing up another cloud of steam.

Flatiron shook his head and trudged on. He felt a chill claw of wind scrape down his back, leaving a wake of shivers. “Not far now. Just one foot in front of the other, and trek’ll soon be over.” The shivers spread to his shoulders, ran down his arms, and curled his fingers into his palms.

A thud startled him. He turned in time to see a second lump of snow slip from a branch in the copse, landing with a solid plop. Where the snow had been now sat a raven, a silhouette of coal against the gray sky. Aiming a squawk at Flatiron, the bird flapped its wings before settling back on the branch. As if by signal, another raven joined it, and then three more.

“Going to Inver, is he?” remarked one of them. “Feeling the cold, too, my word,” came from another. The others piped in. “Shivery weather, ain’t it?” “Don’t let that cloud knock off your hat!” “Watch us. We’re off.” With a noisy rush of wings, the five took flight towards the village. A black feather, streaked with grey and smaller than his thumb, landed on Flatiron’s sleeve. In the sky, the birds shrank to black dots and then dropped out of sight behind the Hill.

“An unkindness of ravens,” Flatiron recited. “A muster of storks. A siege of herons. A cast of hawks. A deceit of lapwings.” He pocketed the feather, his eyes on the rise just ahead. For eighty-two years, he had hiked to the top of the Hill, surveyed the village on the other side, and then decided whether to turn back or keep going. He stopped there now.

Smoke rose from chimneys, anchoring Invermere to the lowering clouds. Ravens swarmed like schools of fish. A red cloth, not yet rigid, flapped on a line. On the Hill’s crest, the wind, scented with animal dung and frozen hay, struggled against him, but Flatiron pushed forward. After a few steps, the wind gave up, and the village rose to engulf him. He gulped one final icy breath before sinking among the houses, where sooty smoke had streaked the walls. Down here, the air tasted of burning peat.

In the shop, where he leaned his snowshoes in a corner, his breath steamed in front of him. He waited quietly while Mrs. Foresight helped a young mother, whose tyke clung to her skirt while staring at Flatiron’s knees. He examined them himself and noted a tiny hole starting in the left knee of his britches. A scar from the morning’s efforts with the firewood.

Mrs. Foresight stared at Flatiron’s chin. “Best to come early and be tucked back in at home ‘fore lunch, cold day like this, innit?”

Flatiron nodded, opened his mouth to speak, but too slowly. The woman had already started up again.

“Your package ain’t come yet, but I expect it next week, just like I told you last time already. Tuesday, after floods clear.” She ducked her head to glance sideways out a window. “Looks bad now, but melt’ll start in two days.” She glanced back at his chin. “You’ll be wanting some bread crumbs. And an onion.”

Whatever for? wondered Flatiron. Yet he paid for the items. Wrapped in yellowed paper and tucked into his deep pocket, they banged against his leg as he left Invermere.

With the wind at his back, the climb out of Invermere was easier, and all his layers warmed him. Densely falling flakes hid Bearded Tor; behind the wall, the sheep wriggled out of snow banks and then huddled more closely together. In the copse, a host of sparrows flitted among the branches, threatening the sleepy owls. A single crow stood sentry on a limb overhanging Flatiron’s path.

From his pocket, he dug out the onion … the packet of crumbs … the feather–which had stretched to the length of his forearm and turned completely grey. Whose feather now? A stork? An ostrich?

Under the sentry’s branch, he proffered the feather. The crow gripped it with a claw and flew off, hoarsely calling, “About time. They’ve been waiting for ages!”

Flatiron scattered the crumbs over the copse and watched the sparrows dip up the meal, bowing and scraping in an avian gavotte. The owls rearranged their feathers.

He stood so long that he began to feel the wind creeping under his cap and scarf and cloak. Snow had buried his snowshoes, and he had to shake them off before starting the last stage of his walk.

The gate stood open, creaking impatiently.

“Yes, yes, you’re quite right. This is no weather to be standing around in.” He gently shut the gate, making sure the latch was tight against the wind. Even before opening his door, he could smell dinner.

While Flatiron’s woolen layers steamed near the hearth, he drank the mug of black coffee that had been made ready for him. Stew bubbled in a heavy pot suspended over the fire.

“The feather. You planned that, didn’t you?” he said. He took another sip. “Am I too late to add the onion?”

By: Lizzie Ross,

on 3/13/2016

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Marcel Proust,

2016 Goals,

Add a tag

Warning: I get a bit philosophical here.

Within a Budding Grove, pp. 488-504

Grand Hotel, Cabourg

Marcel has gone off to Balbec-Plage, in Normandy. After, of course, much anguish about leaving his mother. I suppose it’s all meant to be very touching, but I couldn’t help thinking, “Get on with it, already!” as he moped and worried about how he’d survive in a strange town, with only his grandmother to tend him. (And, of course, the ever-loyal Françoise, who accidentally heads off on the wrong train and arrives much later in Balbec.)

Duguay-Trouin, St. Malo

He does write something worth thinking about at the beginning of this section (“Place-Names: The Place”):

… the better part of our memory exists outside ourselves…. Outside ourselves, did I say; rather within ourselves, but hidden from our eyes in an oblivion more or less prolonged. It is thanks to this oblivion alone that we can from time to time recover the creature that we were, range ourselves face to face with past events as that creature had to face them, suffer afresh because we are no longer ourselves but he, and because he loved what leaves us now indifferent. (pp. 488-489)

Nativity, Great Hours of Anne of Brittany

So, there are at least two Marcels, the “Marcel” who loved Gilberte, and the “Marcel” who doesn’t. How many different selves can there be? According to Marcel, we aren’t one self that gathers layers around it, like the grit in an oyster that becomes a pearl — instead we’re each a cast of thousands, each cast member taking its turn as star, created by a new emotion, only to be pushed off-stage by the next star.

Maybe. The backstage area must get crowded, as a person gets older. Imagine the noise and confusion! “Five minutes, 1981 broken-hearted-over-Joe self! Five minutes.” And the 1981 self pushes forward, to cameo in a brief moment of regret about that idiot Joe. Oops! Did my 1981 self try to upstage me there? “Back!” I say, “Back!”

Final great quote: “a casino, over which a flag would be snapping in the freshening breeze, like a hollow cough” (p. 503) — doesn’t bode well for the casino, does it?

I have to wonder now whether Proust’s multi-selves are one version of the multiverse — all those infinities are within us rather than in a set of parallel worlds. Walt Whitman: “I contain multitudes.”

Tomorrow: a break from WTWP for some of my own fiction.

By: Lizzie Ross,

on 3/12/2016

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Marcel Proust,

2016 Goals,

Add a tag

First week of January, 2011, must have been quiet, for I made wonderful progress in Proust, reading whom is like watching a glacier. Things move too slowly to notice changes over short periods of time (or just a few pages) — you need great distances, huge chunks of text, to see anything happening.

Botticelli’s Magnificat

Within a Budding Grove, pp. 416-487

If Ralph Vaughn Williams had composed with words, he might have written the last few pages of “Madame Swann at Home”. Such lyrical beauty, with all those flowers and colors, as Mme. Swann walks along a Parisian avenue on a sunny May afternoon, surrounded by a crowd of men. Marcel practically drools over her.

It’s a fitting end to this episode, 150 pages of Marcel agonizing over Gilberte Swann, who, his readers can immediately see, barely tolerates him. He doesn’t hide the painful scenes.

Mme Swann’s samovar was “metallic red”

Finally, Marcel gets the message (Gilberte lets her boredom show), and he goes all noble. He stays away from her, hoping that this will make her realize how much she loves him, but also reasoning that the longer he stays away from her, the less he’ll love her. It’s a very complicated sort of logic: He knows she doesn’t love him, yet can’t help hoping that perhaps she does. He stays away, to cure his obsession, but also in hopes that the separation will end in a happy reconciliation.

There are hints of future loves with others, specifically to Albertine. But he hints that his affair with Albertine will be just as unhappy as his current one with Gilberte. You can’t help feeling that Marcel tends to love in all the wrong places. Also, his fascination with Mme. Swann is a bit suspect, but I have to let that go; he’s so honestly confessional that, if he’d been infatuated with her, he’d have written about it.

Luini’s Adoration of the Magi

Some great quotes in these pages:

… there is nothing that so much alters the material qualities of the voice as the presence of thought behind what one is saying. (p. 419) [I can’t resist a nod to the current presidential campaigns.]

It is what I should have said then and there to Bergotte, for one does not invent all one’s speeches, especially when one is acting merely as a card in the social pack. (p. 435)

We imagine always when we speak that it is our own ears, our own mind that are listening…. The truth which one puts into one’s words does not make a direct path for itself, is not supported by irresistible evidence. A considerable time must elapse before a truth of the same order can take shape in the words themselves. (p. 465)

Guelder-rose

During those periods in which our bitterness of spirit, though steadily diminishing, still persists, a distinction must be drawn between the bitterness which comes to us from our constantly thinking of the person herself and that which is revived by certain memories, some cutting speech, some word in a letter that we have had from her. (p. 476)

And this, from a Marcel in the depths of despair about Gilberte:

We construct our house of life to suit another person, and when at length it is ready to receive her that person does not come; presently she is dead to us, and we live on, a prisoner within the walls which were intended only for her.

Victoria carriage

I wipe away the tears, just as Marcel presents that paean to Mme. Swann, in her spring attire, shaded by a parasol the color of Parma violets. She has left the victoria at home and is walking gaily, creating a memory that Marcel will treasure, “Mme. Swann beneath her parasol, as though in the coloured shade of a wistaria bower.”

Parma violet, photo Courtesy of M. Pierre Barandou, Geraniums d’ Aquitaine, S.A., Agen, France, AmericanVioletSociety.org

A note about the images: like any successful author, Proust immerses readers in a world that would have been immediately recognizable to contemporaries but becomes more obscure as time passes. Thanks to film and the internet, it’s possible to locate or recall Gilded Age interiors, fashions, manners, and even plants and trees. But Proust goes further, referencing works of visual and musical art. In a future life I may track down the musical references, but for now I’m satisfied if I can find images of the art, whether natural or man-made, that plays meaningful roles in this novel. Somehow, in the original post, I didn’t include a photo of a Parma violet, so I add it here. Colors are as important to Proust as any other visual image.

By: Lizzie Ross,

on 3/11/2016

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Marcel Proust,

2016 Goals,

Add a tag

Remember my reader who commented that one must reread Proust? I wonder if that was a subtle curse. Judge for yourself as you read the next update.

Within a Budding Grove, pp. 406-416

Mathilde Bonaparte, courtesy Wikipedia

So, as I was plodding away this week, hiking through Proust’s dense prose, I started to notice something weird, something akin to déjà vu. The narrator seemed to be repeating himself. The occasional passage was like an echo of something I’d read earlier, and Marcel was suddenly younger and once again out of favor with the Swann’s. It didn’t make sense, but I figured Marcel had his reasons for the repetitions and would eventually explain what was going on.

Then it hit me, like a kick in the shin: I’d started reading at page 306, when I should have begun at 406! Very irksome, for two reasons. First, of course, is that I wasted a half hour re-reading 5 pages from Swann’s Way. And second: that I didn’t notice sooner. Most of those 5 pages seemed brand new. Had I not been paying attention when I read them the first time? Oy!!!

So, back to Marcel in his proper place, hanging out with the Swanns and pining away for Gilberte. He even makes the explicit comparison to Swann’s initial frustrated love for Odette but goes no further with the analogy.

I heard on the radio a few days ago that worry is future-focused. This is definitely Marcel. He (so far) has no regrets (which are, clearly, past-focused; the related present-focused emotion has to be fear, which Marcel exhibits only as reluctance to approach adults). For the most part, Marcel is a worrier — will Gilberte ever realize that she loves him? will she ever express this love? will she be at home? will she speak with him? etc., etc., mutatis mutandis.

Yet it’s a strange relationship. Marcel seems to be more appreciative of Gilberte’s parents than he is of her. He writes of going out in the carriage with M. and Mme. Swann, and I picture the three of them (who knows where Gilberte is? who cares?) driving through the Bois, bowing to various personages. Marcel looks admiringly at Mme. Swann and imagines the admiration and jealousy that others feel when they see him with her.

Then, out of the blue, Mme. Swann introduces him and Gilberte to someone they meet — Gilberte’s been there all along! And just as quickly she moves into the background. On these excursions, she says nothing, and Marcel thinks only of her parents. Very odd.

Are his affections changing? Not really. I suspect this is more of what he has touched on earlier, the idea that anticipation is much more exciting that reality. Thinking about Gilberte is more satisfying than being with her, even if she’s actually there.

These few pages end with a tiff between Gilberte and her father, about going to the theater on the anniversary of her grandfather’s death. M. Swann doesn’t want her to go, but she refuses to submit. “I think it’s perfectly absurd,” she explains to Marcel, “to worry about other people in matters of sentiment. We feel things for ourselves, not for the public.”

The tiff transfers to Gilberte and Marcel when he, emulating Swann, tries to stop her.

“But Gilberte,” I protested, taking her by the arm, “it is not to satisfy public opinion, it is to please your father.”

“You are not going to pass remarks upon my conduct, I hope,” she said sharply, plucking her arm away.

Les Invalides, courtesy Wikipedia

Marcel, in supporting the father’s wishes, risks losing the daughter.

A note about dates: a chance meeting between the Swanns and Princess Mathilde in the Jardin d’Acclimatation leads to a reference to Tsar Nicholas II’s visit to les Invalides (the site of Napoleon’s tomb), a visit which, after just a few moments on the internet, can be dated to October 1896. FYI: Dreyfus was first convicted in 1894, evidence implicating someone else was discovered (and suppressed) in 1896, Zola wrote J’Accuse! in 1898, and Dreyfus was finally exonerated in 1906. I don’t know what the Swanns talk about when they’re on their own, but in front of Marcel they seem totally unaware of the anti-Semitic storm that’s raging around them.

There’s something about December afternoons, with the days shortening and chill winds or damp rain pressing against my windows — ideal napping weather. This post dates from early December 2010, with big family holidays nearing.

But now it’s a warm March morning as I reblog this post, and the dangers of dozing over Proust are the same in any season. Good thing Proust offers gems like the one I discuss below.

Dreyfus (photo H. Roger-Viollet)

Within a Budding Grove, pp. 386-406

Lesson 1: Don’t read Proust while in a reclining position (say, on one’s couch), wrapped in layers of blanket, on a rainy afternoon. I kept falling asleep through most of the latest 20 pages, so it took me about 5 hours to make this week’s meager progress. To paraphrase The Who, hope I finish before I get old!

Lesson 2: Even 20 pages of truly dense ruminating prose can hold some gems. For example, this section reminded me of the social one-up-manship well known to all Luciaphiles.

Although Tilling may equal only the tiniest corner of middle-upper-class Paris, the scrabble to get on top and stay there — and to be sure that everyone knows you’re on top — is the same in both places. As Odette and Charles aim for the best guests and pretend not to care, I could see Lucia and Georgie conniving against Daisy (for her guru) and Mapp (for Mallards). Did E. F. Benson read Proust?

One of the best lines is from Marcel’s mother, who watches the Swanns’ social contortions with total comprehension. Marcel’s father can’t understand why they’d want to invite someone so low-class and low-value as the Cottards, but his mother gets it:

Mamma, on the other hand, understood quite well; she knew that a great deal of the pleasure which a woman finds in entering a class of society different from that in which she has previously lived would be lacking if she had no means of keeping her old associates informed of those others, relatively more brilliant, with whom she has replaced them. Therefore, she requires an eye-witness who may be allowed to penetrate this new, delicious world (as a buzzing, browsing insect bores its way into a flower) and will then, as the course of her visits may carry her, spread abroad, or so at least one hopes, with the tidings, a latent germ of envy and of wonder. Mme. Cottard, who might have been created on purpose to fill this part, belonged to that special category in a visiting list which Mamma … used to call the ‘Tell Sparta’ people.

We all know a few Tell Sparta people, but to what extent do we cynically use them to engender envy as they broadcast news of our party guests?

NB: The Dreyfus affair enters the scene, briefly, in this section, and for the first time (I think, although I might have missed earlier references), Marcel states that the Swanns are Jewish. After reading de Waal’s memoir, these overlaps with the Paris branch of the Ephrussi family resonate.

Here’s a reaction to the original post:

au contraire! you must read Proust lying down! you *must fall asleep every page! you must reread the same section over and over again without noticing! it must NOT make sense, either!

whatever gives you the notion that Proust is a book like any other — one to be read (Damn, English lacks perfected forms of verbs! I must improvise!) … read from cover to cover rather than read in (or better yet, “read about”)?? hain?!

one reads in Proust, not reads Proust!

give it up!

i have been reading Proust for three years and have not yet made it through book one!

It’s nice to be confirmed in my belief that I’m not the only one. Rereading this response, however, just makes me more determined: this is the year I finish Proust.

Interspersed with my summaries of and reactions to Proust’s novels are a few posts on related topics, highlights of which I’ve excerpted and combined below. It amazed me at the time how Proust-related books and articles would fall into my lap. Coincidence? Serendipity? Whatever the case, it’s all very interesting.

Courtesy Flickr, ilvic

Edmund de Waal’s The Hare with Amber Eyes, reviewed in the NYRB (Oct. 14, 2010) reveals a possible connection to Proust, for de Waal’s great-grandfather’s cousin, Charles Ephrussi, could have been an inspiration for Swann.

de Waal is a potter/artist (beautiful work; photos of his installations are available on his website; he’s also recently published a new book, The White Road, a history of porcelain) who inherited a huge collection of netsuke from a great uncle. This inheritance sent him on a journey through Europe and Asia, tracing the netsuke through generations of family members who had owned them. It’s a book about outsiders (Jews, artists, collectors, homosexuals) that perfectly matches Proust’s work.

Gustave Caillebotte

In the first few chapters of de Waal’s book we find where the real Charles Ephrussi overlaps with the fictional Charles Swann. Ephrussi develops an all-consuming interest in Dürer, Swann in Vermeer. Ephrussi hangs out in Mme Lemaire’s salon, Swann in Mme Verdurin’s. Ephrussi’s religion separates him from polite society, whereas for Swann it’s his marriage.

De Waal references Caillebotte’s painting (right), Jeunne homme à sa fenêtre, saying it could easily be Charles Ephrussi on his arrival in Paris:

Here [he] stands at the open window of their family apartment looking out onto the intersection of the rue de Monceau’s neighbouring streets. He stands with his hands in his pockets, well dressed and self-assured, with his life before him and a plush armchair behind him. ¶Everything is possible.

A sense of wealth exudes from this portrait, as well as from de Waal’s memoir. The Ephrussis had an astonishing amount of money, with family homes across Europe — a different one for each season, plus 2 or 3 more for side excursions. Those were the days, my friend!

Charles Haas

Trolling through a French wiki brought me this bit of info about another possible model for Charles Swann (my mediocre translation from the original French):

Charles Haas, “marvelously endowed with intuition, finesse and intelligence” (Boni de Castellane), had a fortune large enough to save him from having to earn a living. de Castellane adds, “Shy due to his Jewish heritage, he was the only one of his race (all poor) who was a friend to all women, was cherished in the salons, and was appreciated by men of good taste. He gave to this category of the spiritually and uselessly idle that were like a luxury in the society of those days, and of whom the main value consisted of being able to gossip, before dinner, at the Club Jockey or at the Duchess of Trémoille’s home. His lack of a job didn’t spur him to try harder; rather, his intelligence was justification enough for all his ambitions.”

Charles Haas was a regular at literary salons, especially those of the Countess Robert de Fitz-James and Mme Emile Straus, at public auction houses, the lobby of the Comédie-française, at the ateliers of painters, particularly that of Degas, whom he had met at the home of Mme Hortense Howland.

Le Cercle de la Rue Royale, courtesy Wikipedia

How thoughtful of the wiki to reproduce a painting by James Tissot, where Haas is depicted in the top hat at the far right. Another note of interest: Haas was one of Sarah Bernhardt’s lovers.

Note that Haas’s shyness about his Jewish blood overlapped l’affaire Dreyfus and Zola’s “J’accuse!” Heady times! (BTW, see Jacqueline Rose’s essay in the 10 June 2010 LRB for a great exploration of Zola’s continued relevance, more than 100 years later. Great writing, and dedicated to the late Tony Judt, one of my favorite public intellectuals.)

Source of Charles Haas’ image and original French text: Dictionnaires et Encyclopédies sur ‘Academic’. More information about Tissot’s painting can be found at the Musée d’Orsay’s website.

That’s enough for one set of excerpts.

This post’s title was “Per viam rectam”, which I explain at the end. The post is dated October 29, 2010, just before I wrote the first draft of what became Kenning Magic. Make of that what you will.

Within a Budding Grove, pp. 369-382

The Trocadero, Paris

After a hectic week, it was a pleasure to sit down with Marcel and read a few pages. Proust’s text takes me away from the madness of NYC — the noise and crowds and torn up streets that have made cycling to work this week a daily challenge — and into the calm of poor Marcel’s infatuation with Gilberte.

Yes, he’s still going on about her. But in this section he crosses a threshold, literally. After hearing that Mme. and M. Swann “can’t abide” him, Gilberte suddenly begins inviting him to tea, where the Swanns treat him with polite distancing. Before, he would stand in the street and stare up at Gilberte’s windows, imagining what went on up there. But now, he stands at the window and looks down on the street, to see other guests arrive.

Palais de l’Industrie, Paris

It’s very sweet to see him finally spending time with Gilberte, finally allowed entré to the world of the Swanns, but I can’t help wondering if there isn’t some kind of disaster waiting for him. We’ll see.

One passage stood out as Marcel rues writing an impetuous letter to Gilberte stating his wish for more time with her. No response comes, and it nearly crushes him:

I had spent the New Year’s Day of old men, who differ on that day from their juniors, not because people have ceased to give them presents but because they themselves have ceased to believe in the New Year. Presents I had indeed received, but not that present which alone could bring me pleasure, namely a line from Gilberte. I was young still, none the less, since I had been able to write her one, by means of which I hoped, in telling her of my solitary dreams of love and longing, to arouse similar dreams in her. The sadness of men who have grown old lies in their no longer even thinking of writing such letters, the futility of which their experience has shewn.

And then, a few lines later, thinking about Berma surrounded by admirers but inured to their attentions, the older Narrator wonders if a letter from Gilberte could have fulfilled Marcel’s expectations:

At that moment, a message from Gilberte would perhaps not have been what I wanted. Our desires cut across one another’s paths, and in this confused existence it is but rarely that a piece of good fortune coincides with the desire that clamoured for it.

“The sadness of men who have grown old” and “this confused existence.” Melancholy phrases for an autumnal day.

BTW: The post title, “per viam rectam” can be found in Psalms 107:7 (et duxit illos per viam rectam/And he led them forth by the right way), and it’s the motto on the Gilberte’s stationery. Even more reason to worry about Marcel.

I’m going to have to do something about the search function on my other blog, because I’ve just found several additional Proust posts. I knew something was strange when Update #9 took me only to p. 344, yet when I had stopped reading all those years ago, my bookmark had been placed at p. 530. A search has revealed further posts, which I’ll repost here in a quick barrage over the next week or so. This one followed a 6-week hiatus from Proust’s novel.

Within a Budding Grove, pp. 344-368

Cellini’s Perseus

Yes, it’s time we returned to Proust. Let’s see what Marcel has been up to recently.

If you recall, he’s just seen Berma, the famed actress, and was disappointed. It seemed boring, monotonous, uninspired. Nothing at all like the performance he had imagined he would witness, and he begins to worry that life will be full of similar disappointments. Yet the wild applause at the final curtain makes him doubt his first assessment:

Then, at last, a sense of admiration did possess me, provoked by the frenzied applause of the audience … the more I applauded, the better, it seemed to me, did Berma act.

I love the next few lines:

“I say,” came from a woman sitting near me, of no great social pretensions, “she fairly gives it you, she does; you’d think she’d do herself an injury, the way she runs about. I call that acting, don’t you?” And happy to find these reasons for Berma’s superiority, though not without a suspicion that they no more accounted for it than would for that of the Gioconda or of Benvenuto’s Perseus a peasant’s gaping “That’s a good bit of work. It’s all gold, look! Fine, ain’t it?”, I greedily imbibed the strong wine of this popular enthusiasm …

Can we trust our first impressions? Or do we allow popular enthusiasms to influence us?

M. de Norpois joins Marcel’s family for dinner that night, and pontificates on art, politics, diplomacy and food. (At one point he begrudgingly tastes a dessert, with the comment, “I obey, Madame, for I can see that it is, on your part, a positive ukase!”) His conversation is full of references to his wide experience, quoting or translating proverbs from other lands, including one from Arabic about how one should respond to criticism: “The dogs may bark; the caravans go on!”

Marcel is so enchanted by M. de Norpois’ hauteur and diplomatic demeanor (gained from extensive experience in The World At Large) that he practically worships the man, and at one point is thrilled to think that M. de Norpois might actually mention Marcel’s name to Mme. Swann — she would then realize that Marcel knows the ambassador and would thus be willing to welcome the boy into her home.

M. de Norpois convinces Marcel that Berma’s performance was good, that Marcel’s favorite writer, Bergotte, is a hack, and that Marcel’s best writing is a poor imitation of Bergotte’s worst. In short, the old man crushes Marcel, yet the poor boy only sees this as illumination.

I can’t help wishing Marcel could be loyal to his own ideas, less under the influence of the huge celestial bodies that surround him, but I suppose it’s inevitable. Gravity can’t be denied.

There’s a long bit at the point where Marcel, still hoping de Norpois will put in a good word for him with the Swanns, momentarily mimes the action of kissing the old man’s hands. The older Marcel considers this moment from a more informed distance, posing the idea that we are all so insecure about our abilities to have an impact on the world that we imagine no one notices anything that we do (it’s the “20 years from now, who’s going to know the difference” attitude).

The older Marcel (our Narrator) tells us that the younger Marcel thought de Norpois had missed the gesture,

And yet, some years later, in a house in which M. de Norpois, who was also calling there, had seemed to me the most solid support that I could hope to find, because he was the friend of my father, indulgent, inclined to wish us all well, and besides, by his profession and upbringing, trained to discretion, when, after the Ambassador had done, I was told that he had alluded to an evening long ago when he had seen the moment in which I was just going to kiss his hands, not only did I colour up to the roots of my hair but I was stupefied to learn how different from all that I had believed were not only the manner in which M. de Norpois spoke of me but also the constituents of his memory …

Ambassadors may have high levels of discretion, but it seems this one, at least, had no ability for empathy.

Marcel makes one other point about M. de Norpois:

… like all capitalists, he regarded wealth as an enviable thing, but thought it more delicate to compliment people upon their possessions only by a half-indicated sign of intelligent sympathy; on the other hand, as he was himself immensely rich, he felt that he shewed his good taste by seeming to regard as considerable the meagre revenues of his friends, with a happy and comforting resilience to the superiority of his own.

If only the younger Marcel had known all this. But at least the older Marcel gets his revenge — by including this story, and this perfect caricature, in some truly celestial writing.

More on first impressions and popular enthusiasms, in this truly wacky U.S. election year. I know Proust does not have politics in mind as he reveals Marcel’s malleability, but I can’t help wondering if Proust noticed similar tendencies in the body politic. I know the Dreyfus affair comes into the story, so there’s at least one chance for the author to address my question. We’ll have to see what happens.

This is the last of my Proust posts from 2010. After this, it’s sauve qui peut!

Within a Budding Grove, pp. 326-344

Allee

Marcel’s musings on the Bois de Boulogne, at the end of Swann’s Way, made me want to hop on a plane and stroll along its allées, looking for hints of Paris 130 years ago. I took the cheaper route instead, and watched Gigi, which begins and ends in the Bois, and whose lead characters are very much like Odette and Swann.

But now, I’ve moved on to the next volume, which starts with a long introduction to a performance by Mme. Berma (based, no doubt, on Sarah Bernhardt) in Racine’s Phèdre. In Marcel’s imagination, Berma is god-like, someone to be worshipped, and he works himself into an emotional frenzy at the thought of finally seeing her on stage in a classic of French theater. Will the doctor and his parents give permission? Will there still be tickets left? Should he, perhaps, not go, because going might make his parents unhappy? But when will Berma ever again perform in Phèdre? Oh, what to do?

Titian’s Assumption, Venice

Of course, such high expectations can only end in disappointment, and we can see it coming well before Marcel does.

He has a tendency to romanticize about art, envisioning the moments when he sees famous works for the first time in situ. There’s a bit about Venice — though he hasn’t been there yet, he expects certain works by Titian and Carpaccio will be not just stunning, but an experience akin to ecstasy — and his dreams of seeing Berma are similar.

I know the feeling. My first view of da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in The Louvre was a disappointment. It was so small! There was no frisson of emotion at being so close to a legend. (Nothing like what I felt one evening, when I saw Lauren Bacall standing behind me at the entrance to a play.) I expected something within me to change upon seeing that famous portrait, but nothing happened.

Marcel’s and my disappointments upon meeting our dreams in real life raises two questions: Are our most thrilling imaginings always betrayed by real life? Would we give up those imaginings, in exchange for no more betrayals?

Chocolate madeleines, peppermint tea, my kitchen

I know I wouldn’t, and I suspect Marcel (and Proust) would agree. Despite the frequent betrayals, there’s always the possibility of greatness that goes beyond our most reckless fancies, and that’s what we hope for as we jump into each new experience, regardless of previous failures.

Dr. Johnson called remarriage “the triumph of hope over experience”; the same could be said of life in general. Marcel keeps hoping — that Gilberte will finally realize she’s in love with him, that art will finally live up to his expectations, that his parents will finally recognize his genius as a writer.

Well, let’s see where Marcel’s dreams take him next, as we continue chez Mme. Swann.

My reviews so far seem to have stressed Swann’s and Marcel’s disillusionments. I’m hoping for a shift in tone, but we’ll see. Keep in mind, however, that the next 1500 pages (!) will pass slowly, perhaps lasting through the end of this year. Since I overlap books — sometimes as many as five at a time — I’ll be sprinkling some other reviews here and there, as time permits. Now, onward and upward!

By: Lizzie Ross,

on 2/21/2016

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Marcel Proust,

2016 Goals,

Add a tag

I don’t know whether to be encouraged or dismayed that it took me 8 weeks to read a bit over 300 pages, an average of about 36 pages a week. Someone recently pointed out that I’d do better with a 6-volume edition — larger type, fewer words per page, minimal soporific effect. But I’m too stubborn to take the advice — I’ll stick with my 2-volume set, bought at a used book store in 2009. But I know now not to read it in bed, or even in a comfy chair. I must sit at a table, notebook at my side, if I’m to expect any progress.

pp. 293-325

C. Guys: Une femme dans une victoria

I’ve finished Vol 1: Swann’s Way, and the next stage is Vol 2: Within A Budding Grove.

Swann’s Way ends on a melancholy note, which I’ll get to in a bit, but recall that Marcel has become obsessed with Gilberte Swann, an obsession that mirrors Swann’s feelings for Gilberte’s mother, Odette. It’s all such familiar territory to us, and to Marcel as well, for he at one point makes the connection.

This section of the volume is also about the power of names — of almost anything: trees, flowers, streets, as well as people — to evoke emotions and memories. Just like the flavor of the madeleines dipped in tea, these words call up images and moments with Gilberte that the narrator can now savor, with more enjoyment than he had while actually immersed in them, because at the time he was too busy worrying when he would next see her.

In one long sentence, Marcel presents his image of a perfect relationship with Gilberte (the same sentence in which he notes the resemblance of his obsession with Swann’s for Odette), his emotions having evolved from loving her because he knew so little about her, to loving her because she had just given him a book he had mentioned wanting. He calls this change a “reincarnation,”

… discarding my own separate existence as a thing that no longer mattered, I thought now, as of an inestimable advantage, that of this, my own, my too familiar, my contemptible existence Gilberte might one day become the humble servant, the kindly, the comforting collaborator, who in the evenings, helping me in my work, would collate for me the texts of rare pamphlets.

I had to laugh at that final phrase, at the image of worldly Gilberte giving up so much, to sit beside Marcel in a candle-lit room, messing about with yellowed publications. So much for romance!

1880

1910

And the melancholic ending? It’s all about the futility of revisiting old haunts, because you won’t see what you once saw. An adult Marcel goes back to the Bois de Boulogne, where he used to see an elegant Mme. Swann walking, or riding in her victoria, in gowns and hats no longer in fashion. The older Marcel misses the styles, which have been replaced by “Greco-Saxon tunics, with Tanagra folds, or sometimes, in the Directoire style, ‘Liberty chiffons'”. And the men? “They walked the Bois bare-headed.” Gone are the “tile hats” (top hats), so distinguished, and so appropriate for a sweeping salute to ladies met along the way.

Here are the last few lines of Swann’s Way:

[I understood] how paradoxical it is to seek in reality for the pictures that are stored in one’s memory, which must inevitably lose the charm that comes to them from memory itself and from their not being apprehended by the senses. The reality that I had known no longer existed. It sufficed that Mme. Swann did not appear, in the same attire and at the same moment, for the whole avenue to be altered. The places that we have known belong now only to the little world of space on which we map them for our own convenience. None of them was ever more than a thin slice, held between the contiguous impressions that composed our life at that time; remembrance of a particular form is but regret for a particular moment; and houses, road, avenues are as fugitive, alas, as the years.

It’s a perfect explanation of why going back to a house where you once lived, or to any place that holds critical memories, always results in a let-down.

And now, on to Vol 2., which begins with a long section called “Madame Swann at Home.”

Roger Shattuck calls Marcel’s inability to be in the moment “soul error” (“the incapacity to give full value or status to one’s life and experience”, pp. 84-85) and suggests it may be common to all people, despite Marcel’s belief that it’s something only he suffers, due to a special infirmity. Proust (who, of course, is not Marcel, nor even the much older “Narrator” remembering his past) must have recognized the universality of this infirmity, even if Marcel and the Narrator don’t. This is part of the comedy of Proust’s work: even as the characters moan about how no one knows the trouble they’ve seen, readers can sympathize because we’ve all been there.

Arabella Huntington

One more thing: I never commented on how it is that Swann and Odette married after the end of their affair. Proust doesn’t explain, and we can only guess at why. For propriety? To protect Gilberte? An early version of “settling”? Momentary madness? I recently learned about Arabella Worsham (1851-1924), a wealthy American who began her career much like Odette — only she didn’t marry her child’s father. When he went back to his official family, she found someone much wealthier — C P Huntington, of the transcontinental railroad. She eventually married him, and then, when he died, she married his nephew. She built a world class art collection, sold some of her property to the Rockefellers, donated to charities and Harvard, and was perhaps the wealthiest woman in the U.S. It wasn’t madness that hooked her up with two Huntingtons. I believe it was sheer strength of will. I’d like to believe that’s what dragged Swann into marrying Odette — her own strength of will, to get her a place in society that would allow no one to snub her. This is what Aunt Alicia was talking about in Gigi when she tells her grand-niece, “Marriage is not forbidden to us, but instead of getting married at once, it sometimes happens we get married at last.” This makes me wonder if someday we’ll get a feminist retelling of Swann’s story, from Odette’s point of view.

By: Lizzie Ross,

on 2/14/2016

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

August 2010 was a full month for me, for I was returning to work after a year’s sabbatical. This post was originally dated 20 August, a week before the start of classes, which may explain why I’d read only 12 pages. Of course, there could have been other impediments, including Proust’s writing, a dull point in the story’s progression, or even just sheer laziness. But let’s find out what occurred.

pp. 293-305

A busy week, so not much progress. But I digress.

A treat this week (for me, and, I hope for you): I’ll deconstruct one of Proust’s sentences. Not a long one–that would be way too difficult. Instead, I’ve chosen a shorter one that is still fairly typical of Proust’s style. Here it is:

Among the rooms which used most commonly to take shape in my mind during my long nights of sleeplessness, there was none that differed more utterly from the rooms at Combray, thickly powdered with the motes of an atmosphere granular, pollenous, edible and instinct with piety, than my room in the Grand Hôtel de la Plage, at Balbec, the walls of which, washed with ripolin, contained, like the polished sides of a basin in which the water glows with a blue, lurking fire, a finer air, pure, azure-tinted, saline.

“Ripolin” is paint. I’m sure you’ve figured out that Marcel is basically saying that the rooms at the Grand Hôtel are quite different from those at Combray. Those are the bare bones of this sentence, but Marcel packs in so much more. First of all, we get the initial bit of information–that he envisions many many rooms as he tosses in his bed each night (we knew this from the first section, “Combray”).

Then he shows us the rooms at Combray: “thickly powdered …” etc. The air in these rooms seems thick, almost liquid, “edible”. Full of grains and pollen and imbued (“instinct”) with piety. Note Moncrieff’s syntactic inversion in the phrase “an atmosphere granular, pollenous, edible and instinct with piety”, where he places the adjectives after the noun they describe (thus giving us the French flavor of Proust’s original, “une atmosphère grenue, pollinisée, comestible et dévote” — but raising the question of why Moncrieff translated dévote as “instinct with piety” rather than “pious”).

Grand Hotel, Cabourg

Then the rooms at the Hôtel: Proust compares the painted walls to a basin of clear water. But this part is complicated, because you have to read carefully through all the commas, to figure out what the walls contain. They contain the “finer air, pure, azure-tinted, saline”; that is, air finer than what the walls at Combray hold.

Combray is in the countryside near Paris, Balbec is by the sea. This sentence reveals differences between the countryside and the shore that one senses rather than sees. Anyone who’s been to the ocean after a long time inland will recognize the difference that Marcel describes with such particular detail.

That’s as far as I’ll go with that analysis. But imagine doing something along those lines several times per page, for 2000+ pages! Sometimes my mind glides over these, but sometimes I HAVE to stop and figure out what he’s doing. I know some of the credit goes to Moncrieff, but Proust, even in English, is a gorgeous writer.

So, the plot so far: Marcel is back as an active character (the bit about Swann’s affair with Odette happened before Marcel was on the scene). He was hoping to travel to Venice, but an illness has limited his travels to within Paris, particularly to the Champs-Elysées, where, as luck would have it, he has his second encounter with Gilberte (Odette’s daughter).

And suddenly, we’re back in the world of obsession and disappointment, where the woman (or girl — here, Gilberte) tortures the hero (Marcel) by sometimes showing up and sometimes not. Poor Marcel. It can only end badly.

Three addenda: First, Roger Shattuck adds Venice, despite the canceled trip, to the list of critical “places” in Search, alongside Combray, Paris, Balbec, and Doncières. Shattuck writes, “The image of Venice haunts [Marcel] all his life until he finally makes the journey with his mother long after the desire to do so has passed.” Once again, that theme of disappointed desire.

Second (and no surprise), fictional places in Search, as with Proust’s fictional characters, have their twins in real life. In 1971, Illiers changed its name to Illiers Combray to recognize its role as inspiration for Proust’s novel (despite Auteuil laying its own claim to that role). Balbec’s real-life counterpart is Cabourg, on the English Channel. Proust evidently spent 2 months every summer there for several years, rising late, visiting the casino next door, and then writing late into the night. According to Adrian Tahourdin on the TLS Blog, “As the Proust scholar and biographer Jean-Yves Tadié wrote, “it all began in the Grand Hôtel”. The Hotel’s website offers bookings for a “Memorable Moment”–the Hotel’s chef leads a one-hour class on making madeleines–and lists Le Balbec as one of the Hotel’s restaurants.

Proust’s cork-lined room. Courtesy Bed Writers on Pinterest

Third, for anyone with the linguistic chops, here’s Proust’s original sentence the first in the section “Nom de pays: le nom”:

Parmi les chambres dont j’évoquais le plus souvent l’image dans mes nuits d’insomnie, aucune ne ressemblait moins aux chambres de Combray, saupoudrées d’une atmosphère grenue, pollinisée, comestible et dévote, que celle du Grand-Hôtel de la Plage, à Balbec, dont les murs passés au ripolin contenaient, comme les parois polies d’une piscine où l’eau bleuit, un air pur, azuré et salin.

By: Lizzie Ross,

on 2/4/2016

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

Poor Swann. But also poor Odette. Marcel shows no mercy in what he writes about her, thereby revealing his own snobbery. I already know that the Swann-Odette arc will repeat itself with Marcel and … but I won’t give that away yet.

pp. 236-292, end of “Swann in Love” and beginning of “Place-names: The Name”

Lac du Bois de Boulogne, Courtesy Wikipedia

“For a man cannot change, that is to say become another person, while he continues to obey the dictates of the self which he has ceased to be.”

That quote comes near the end of the section about Swann’s affair with Odette, at the point where he is resigned to ending his torturous affair with her. It comes after much anguish, as he realizes that Odette had been unfaithful to him from the first moment of their liaison, not only with several men, but also with women (in the Bois de Boulogne, no less). Up to this point, he had clutched at his love for her:

In former times, having often thought with terror that a day must come when he would cease to be in love with Odette, he had determined to keep a sharp look-out, and as soon as he felt that love was beginning to escape him, to cling tightly to it and to hold it back.

But finally, it happens. He falls out of love.

This decline begins with Swann’s jealousy, which leads to suspicions that Odette no longer loves him, and culminates with his realization that she never did love him. (The arc here reminded me of Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier, made into a passable film in 1983 by Granada Television. Read the book at Project Gutenberg.)

Bellini, courtesy Webb Gallery of Art

A high point in these pages is Swann’s wish that Odette could die a swift and painless death. In his usual fashion, he connects his own feelings to works of art, this time to Bellini’s portrait of Mahomet II, who

on finding that he had fallen madly in love with one of his wives, stabbed her, in order, as his Venetian biographer artlessly relates, to recover his spiritual freedom.

I realize it’s strange to describe such revenge fantasies as a “high point”, but poor Swann sorely needs someone like Loretta Castorini (Moonstruck) to slap him and shout, “Snap out of it!” Instead, it takes an anonymous letter and weeks of Odette’s denials and careless slips to convince him it’s time to leave Paris for Combray, to escape Odette’s power over him, a step he’d been unable and unwilling to attempt even at the lowest point of his despair.

The section ends with Swann’s exclamation, “To think that I have wasted years of my life, that I have longed for death, that the greatest love that I have ever known has been for a woman who did not please me, who was not in my style!”